-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaFriedreich's Ataxia (GAA)•(TTC) Repeats Strongly Stimulate Mitotic Crossovers in

Expansions of trinucleotide GAA•TTC tracts are associated with the human disease Friedreich's ataxia, and long GAA•TTC tracts elevate genome instability in yeast. We show that tracts of (GAA)230•(TTC)230 stimulate mitotic crossovers in yeast about 10,000-fold relative to a “normal” DNA sequence; (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts, however, do not significantly elevate meiotic recombination. Most of the mitotic crossovers are associated with a region of non-reciprocal transfer of information (gene conversion). The major class of recombination events stimulated by (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts is a tract-associated double-strand break (DSB) that occurs in unreplicated chromosomes, likely in G1 of the cell cycle. These findings indicate that (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts can be a potent source of loss of heterozygosity in yeast.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001270

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001270Summary

Expansions of trinucleotide GAA•TTC tracts are associated with the human disease Friedreich's ataxia, and long GAA•TTC tracts elevate genome instability in yeast. We show that tracts of (GAA)230•(TTC)230 stimulate mitotic crossovers in yeast about 10,000-fold relative to a “normal” DNA sequence; (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts, however, do not significantly elevate meiotic recombination. Most of the mitotic crossovers are associated with a region of non-reciprocal transfer of information (gene conversion). The major class of recombination events stimulated by (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts is a tract-associated double-strand break (DSB) that occurs in unreplicated chromosomes, likely in G1 of the cell cycle. These findings indicate that (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts can be a potent source of loss of heterozygosity in yeast.

Introduction

Several inherited human diseases are a consequence of the expansion of trinucleotide tracts [1], [2]. Although the mechanism by which tract expansions are generated is not yet understood, most of the trinucleotide tracts prone to expansion can form secondary structures such as “hairpin-like” DNA (intrastrand pairing) or triplexes (intramolecular pairing events involving complexes with three paired strands). Friedreich's ataxia is caused by expansion of tracts of the trinucleotide GAA•TTC, a sequence that is associated with triplex formation [3].

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts greater than 40 repeats in length result in an orientation-dependent stall of the replication fork [4], [5]. The stall of the replication fork is observed when the (GAA)n sequence is located on the lagging strand template. Long (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts have high frequencies of contractions and expansions (primarily contractions) in both orientations, although these alterations are somewhat more frequent when the (GAA)n sequences are on the lagging strand template; in our subsequent discussion, we will refer to tracts in this orientation as (GAA)n tracts and the same sequence in the opposite orientation as (TTC)n tracts. The poly(GAA) tracts are also associated with a high rate of double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) and a high rate of terminal chromosome deletions [5]. In addition, (GAA)230 tracts stimulate ectopic recombination between lys2 heteroalles 200-fold more than (TTC)230 tracts [5]. In contrast to the strong orientation-dependence observed in studies of replication fork stalling, DSB formation, and ectopic recombination, the frequency of large-scale expansions of the long (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts is affected only slightly by tract orientation [6].

In addition to studies done in yeast, the properties of (GAA)n•(TTC)n repeats were also examined in bacterial and mammalian systems. In E. coli, (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts stimulate plasmid-plasmid recombination by a mechanism that is dependent on both the orientation and length of the repetitive tract [7]. In mammalian cells, length-dependent expansions of (GAA)n•(TTC)n and (CTG)n•(CAG)n tracts are observed; these expansions are stimulated by transcription, and are observed in non-dividing cells, indicating that they are not initiated by stalled replication forks [8]–[10].

The yeast studies of (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts described above were done in haploid strains. In the analysis described below, we examined the properties of long (230 repeats) and short (20 repeats) tracts on reciprocal mitotic crossovers (RCOs) between homologous chromosomes in diploids. The diploid strains described in the Results section allow the selection and mapping of mitotic crossovers. In addition, crossovers are often associated with gene conversion events, the local non-reciprocal transfer of information near the site of the crossover [11], [12]. Most meiotic gene conversion events reflect heteroduplex formation between allelic sequences, followed by repair of the resulting mismatch [11], [13]. During meiotic recombination in yeast, the length of a gene conversion tract is usually about 1–2 kb [14], although mitotic conversion tracts are often much longer with a median length of 7 kb [15]. In our study, both crossovers and conversion events were mapped.

We find a strong stimulation of RCOs for long (230-repeat), but not short (20-repeat) tracts. This hotspot activity is observed in strains heterozygous, as well as homozygous, for the long tracts, and this stimulation is not substantially affected by the orientation of the tract relative to the replication origin. Analysis of the recombination events suggests that the recombinogenic property of the long tracts is a consequence of a double-strand DNA break (DSB) formed within an unreplicated chromosome.

Results

Experimental system to detect reciprocal crossovers and associated gene conversion events

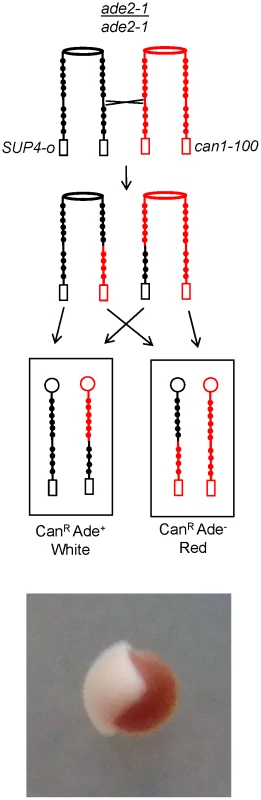

The method allowing the selection and mapping of crossovers and associated gene conversion events is shown in Figure 1 [15]–[17]. A G2-associated RCO can generate two daughter cells that are homozygous for markers that were heterozygous in the starting diploid strain. On one copy of chromosome V, the diploid has the can1-100 allele, an ochre-suppressible mutation in a gene regulating sensitivity to canavanine; yeast strains with the wild-type CAN1 allele are killed by this drug. On the other copy of chromosome V, the CAN1 gene has been deleted and replaced by SUP4-o, a tRNA gene encoding an ochre suppressor. In addition, the diploid is homozygous for ade2-1, also an ochre mutation. In the absence of an ochre suppressor, ade2-1 strains are adenine auxotrophs and form red colonies as a consequence of accumulation of a pigmented precursor to adenine [18]. The starting diploid strain is canavanine-sensitive (CanS), and forms white colonies. A RCO can be selected as a red/white sectored canavine-resistant colony.

Fig. 1. Detection of reciprocal crossovers.

A reciprocal crossover (RCO) in G2 is shown, with chromatids indicated by vertical lines, the centromeres as ovals, and heterozygous polymorphisms as circles. The diploid strains used in this study were heterozygous for the can1-100 allele (an ochre-suppressible mutation) located about 120 kb from the centromere of chromosome V. On the other homologue at the same position as can1-100, the strain had an insertion of SUP4-o, encoding an ochre-suppressing tRNA. The strain was homozygous for the ade2-1 mutation, also an ochre-suppressible mutation. Strains with the unsuppressed ade2-1 mutation form red colonies. The starting diploid was CanS and formed white colonies. An RCO results in two CanR cells that can divide to produce a red/white sectored CanR colony. Polymorphisms distal to the crossover become homozygous in the two sectors. A photograph of a sectored colony is shown below the depiction of the RCO. In Figure 1, we show only one of the two possible segregation patterns, the one in which the recombined chromosomes segregate with the unrecombined chromosomes. If the two recombined chromosomes segregate into one daughter cell and the two unrecombined chromosomes segregate into the other, no canavanine-resistant sectored colony will be observed. In S. cerevisiae, these two segregation patterns are equally frequent [19]. Thus, the rate of RCOs is equivalent to twice the frequency of CanR sectored colonies in the 120 kb CEN5-can1-100/SUP4-o interval [16].

By constructing diploid strains from haploids with diverged sequences, Lee et al. [15] used single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located on chromosome V to map recombination events. Thirty-four polymorphisms that altered restriction enzyme recognition sites were used. Genomic DNA from each sector of a red/white CanR colony was purified and used as a template to generate PCR products containing the SNPs. By treating these fragments with diagnostic restriction enzymes, followed by gel electrophoresis, Lee et al. [15], [17] could determine whether the sector was homozygous or heterozygous for the polymorphism.

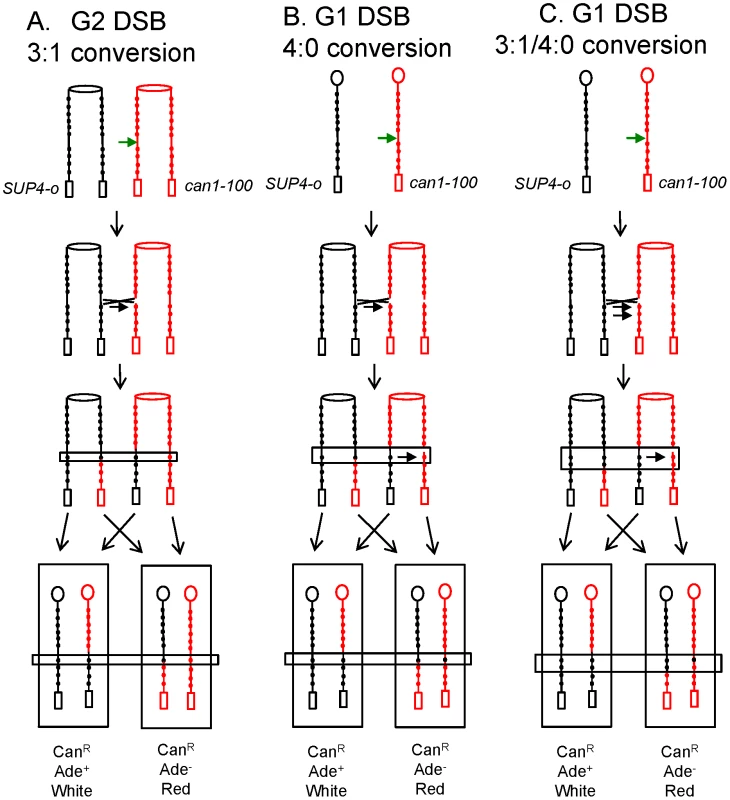

As described in the Introduction, crossovers are frequently associated with gene conversion events. For example, in Figure 2A, we show conversion of one of the polymorphic sites adjacent to the RCO, resulting in the converted allele being found in three of the four chromosomes involved in the initial exchange; this type of event is termed a “3∶1” conversion. These events can be detected by examining the markers in both sectors of a sectored colony. In addition to 3∶1 conversion tracts (Figure 2A), in analyzing spontaneous mitotic crossovers, Lee et al. [15] also found two other types of conversion tracts: 4∶0 tracts (Figure 2B) and 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts (Figure 2C). These events are likely to reflect a DSB in one homologue in G1 of the cell cycle, followed by replication of the broken chromosome, and repair of two broken chromatids in G2. Replication of a chromosome broken in G1 is an expected outcome, since single DSBs formed in G1 do not activate the DNA damage checkpoint machinery [20] and are inefficiently processed to recombination intermediates [21], [22]. If the conversion tracts associated with repair of both DSBs include the same markers, a 4∶0 event is generated. If one conversion tract is more extensive than the other, a hybrid 3∶1/4∶0 event would be observed. This explanation of the spontaneous mitotic RCOs and associated conversions is supported by the observation that the RCOs resulting from gamma-radiation of G1-synchronized yeast cells have 4∶0 and 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts, whereas cells irradiated in G2 do not [17].

Fig. 2. Gene conversion events associated with crossovers in G2 and G1.

The depictions of chromosomes, centromeres, and polymorphic markers are the same as in Figure 1. The regions involved in the conversion event are enclosed within horizontal rectangles. A. 3∶1 conversion associated with an RCO initiated by a double-strand DNA break (DSB) in G2. Following a DSB on the can1-100-containing chromosome, a conversion event in which information is transferred from the SUP4-o-containing chromosome occurs; this conversion event is associated with the RCO. For 3∶1 conversion events, one sector is homozygous for the polymorphic marker and the other sector retains heterozygosity. B. 4∶0 conversion associated with a DSB in G1. One of the unreplicated chromosomes is the target of a DSB, and the broken chromosome is replicated to yield two broken chromatids. The repair of the first chromatid is associated with an RCO and a conversion event. The repair of the second chromatid is unassociated with an RCO but underwent conversion of the same marker. In the resulting colony, both sectors are homozygous for the same polymorphic marker. C. 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid conversion associated with a DSB in G1. As in Figure 2B, the recombination-initiating lesion occurs in unreplicated chromosomes. In this event, however, repair of the first DSB converts two markers, whereas repair of the second converts only one marker. The net result is a 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tract. An alternative explanation of the 4∶0 and 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts is that they represent two independent repair events of DSBs generated in G2. The rate of RCOs in WXT46 is 8.5×10−5/division (Table 1). Of the 29 conversion events associated with the RCOs, 8 were 3∶1 events and 21 were 4∶0 or 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts. If the 3∶1 events are interpreted as the frequency of single repair events in G2, we calculate that the frequency of single events is about 2.3×10−5 ([8/29] × [8.5×10−5]). The expected frequency of independent double events would be (2.3×10−5)2 or about 5.3×10−10. The observed frequency of “double events” (conversion events of the 4∶0 or 3∶1/4∶0 classes) was 5.3×10−5. We conclude, therefore, that the 4∶0 and 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts do not reflect two independent cycles of DSB formation and DSB repair.

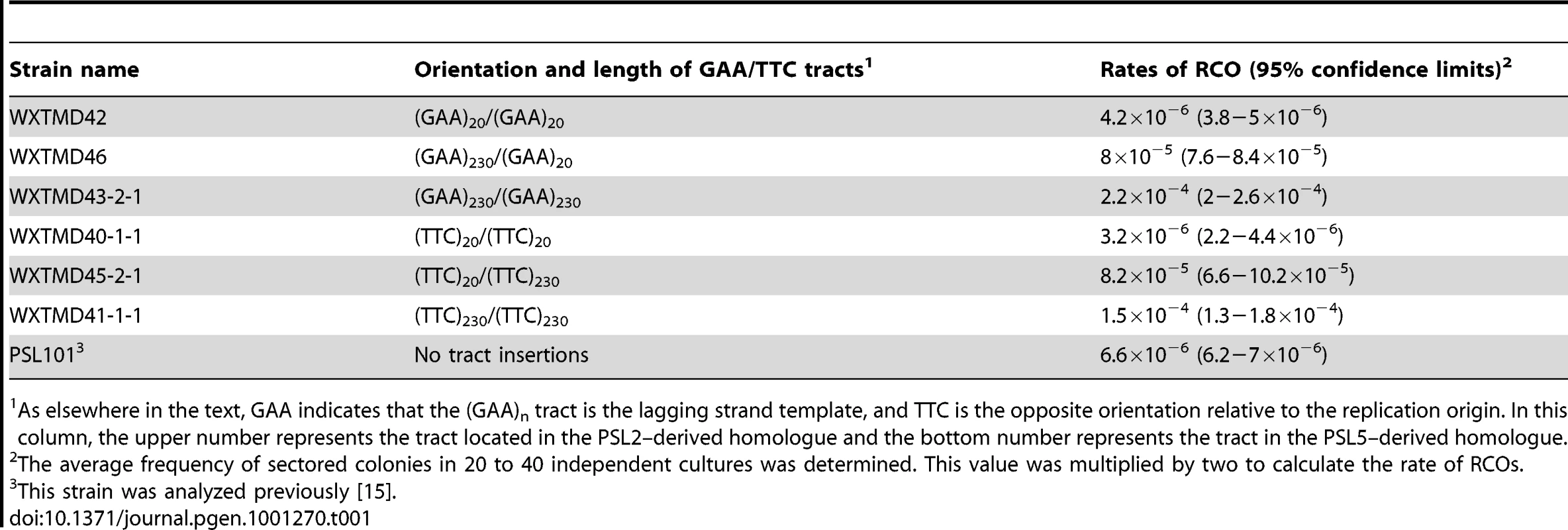

Tab. 1. Rates of reciprocal mitotic crossover in diploid strains homozygous and heterozygous for (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts.

As elsewhere in the text, GAA indicates that the (GAA)n tract is the lagging strand template, and TTC is the opposite orientation relative to the replication origin. In this column, the upper number represents the tract located in the PSL2–derived homologue and the bottom number represents the tract in the PSL5–derived homologue. Orientation-dependent blockage of replication forks for poly GAA•TTC insertions on chromosome V

Previously, we used the system shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 to measure the frequency and location of spontaneous or gamma-ray-induced recombination events in the 120 kb interval between CEN5 and the can1-100/SUP4-o markers on chromosome V. In the current study, we constructed yeast strains with insertions of (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts of two different sizes (230 and 20 repeats) in two different orientations near the URA3 gene on chromosome V (details of the constructions in Text S1). In the strains used in our study, the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts are embedded within lys2 sequences inserted in the intergenic region between GEA2 and URA3. This position is about 22 kb centromere-proximal to ARS508 and about 31 kb centromere-distal to ARS510; both of these ARS elements are active origins [23].

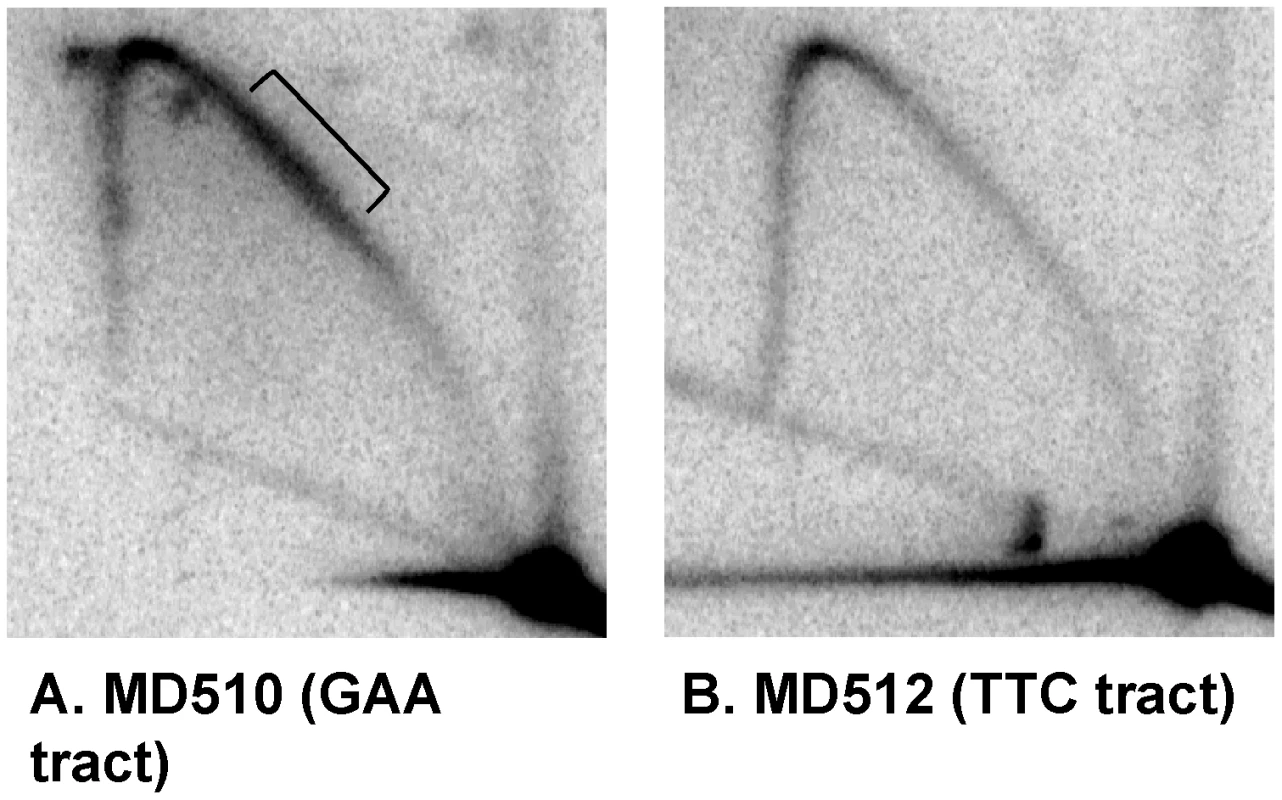

In previous studies [4], [5], it was shown that long (>100-repeat) (GAA)n tracts on the lagging strand template result in a replication fork block whereas long TTC tracts on the lagging strand template do not. To determine how replication forks were blocked for strains with the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts inserted on chromosome V, we constructed two isogenic haploid strains in which a (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tract was inserted in two orientations. In the haploid MD512, the tract was oriented such that the GAA sequence was on the “Watson” strand as designated in Saccharomyces Genome Database, and the haploid MD510 had the tract in the opposite orientation. By two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, we found a blocked replication fork in MD510 but not in MD512 (Figure 3). Since a replication fork initiated at ARS510 would encounter the GAA tract on the lagging strand in MD510, this result suggests that tracts are replicated primarily by a replication fork initiated at ARS510 rather than ARS508, although we have not directly examined fork movement. In our subsequent discussion of yeast strains, tracts oriented in the same direction as MD510 will be termed “(GAA)n” tracts and those with the opposite orientation will be termed “(TTC)n” tracts; this nomenclature is consistent with previous studies [5]. It should be noted that, in other genetic backgrounds, the chromosomal region in which we inserted the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts is replicated using forks that move in the opposite direction from the one observed in our genetic background [24].

Fig. 3. Two-dimensional gel analysis of replication forks stalled by the (GAA)230 tracts.

We examined replication forks in two strains, MD510 and MD512 by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (details in Materials and Methods). These strains were identical except for the orientation of the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts. Accumulation of replication intermediates leads to a “bulge” on the Y-arc (indicated by brackets) in MD510 but not in MD512. Thus, we define the orientation in MD510 as the GAA orientation and the opposite orientation as TTC. (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts stimulate the frequency of mitotic RCOs

We first performed a pilot experiment to examine the recombinogenic effects of (GAA)230 and (TTC)230 tracts in diploids heterozygous for insertion near URA3. As described above, the rate of RCOs in the CEN5-can1-100/SUP4-o interval can be calculated from the frequency of CanR red/white sectored colonies. The rates of RCOs in MD506 (heterozygous for the [GAA]230 tract) and MD508 (heterozygous for the [TTC]230 tract) were 13×10−5/division (±3×10−5) and 6.2×10−5/division (±2×10−5), respectively; 95% confidence limits are shown in parentheses. The rate of RCOs in an isogenic diploid without the tract insertion is 5.8×10−6/division [15]. Thus, the heterozygous tract insertions stimulated RCOs in the CEN5 to can1-100/SUP4-o interval by about 10 - to 20-fold and tracts in both orientations were recombinogenic.

The diploids MD506 and MD508 did not have the polymorphisms required to map the recombination events (details of their genotypes in Text S1 and Table S1). Consequently, we constructed six other diploids that were heterozygous for polymorphisms that allowed mapping of RCOs and associated conversions. The strain names, and their tract sizes and orientations are: WXTMD42, (GAA)20/(GAA)20; WXTMD46, (GAA)230/(GAA)20; WXTMD43, (GAA)230/(GAA)230; WXTMD40, (TTC)20/(TTC)20; WXTMD45, (TTC)20/(TTC)230; WXTMD41, (TTC)230/(TTC)230. In all strains, the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts were inserted at the same position on chromosome V near the URA3 gene (green rectangles in Figure 4). These diploid strains were constructed from two haploid parents (PSL2 and PSL5) with numerous sequence polymorphisms allowing mapping of the positions of the crossovers as described further below.

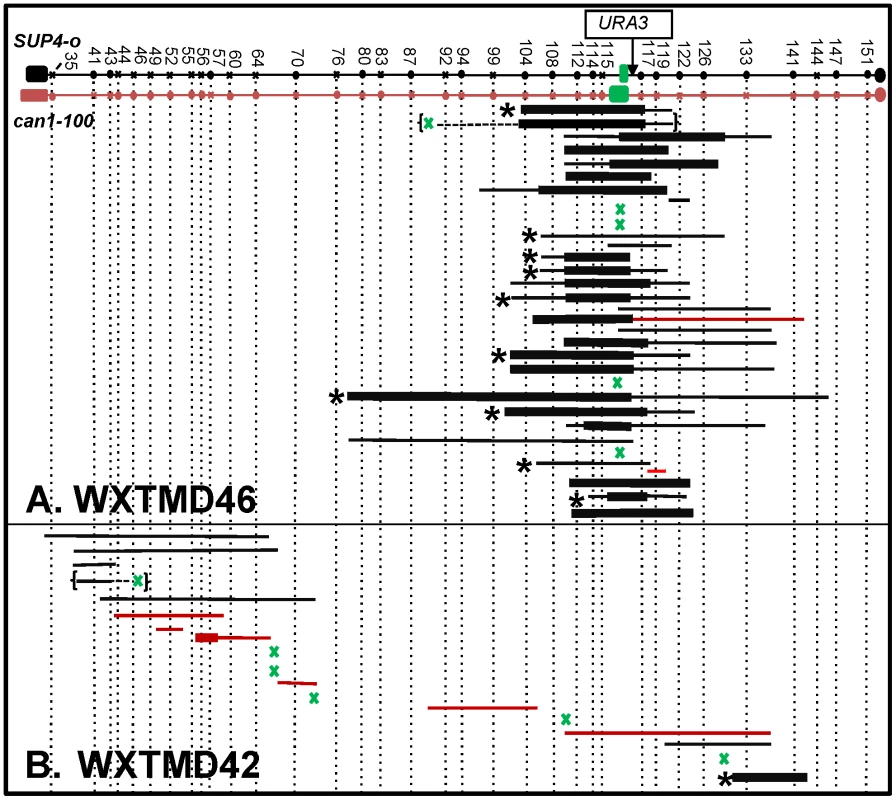

Fig. 4. Mapping of RCOs and associated gene conversion events in WXTMD46 (GAA230/GAA20) and in WXTMD42 (GAA20/GAA20).

The two horizontal lines at the top of the figure represent the two copies of chromosome V of the diploids with black showing the chromosome derived from the haploid PSL5/YJM789 background and red indicating the chromosome derived from PSL2/W303a. The green boxes show the position and approximate sizes of the (GAA)n tracts in WXTMD46. In WXTMD46, the “black” chromosome contains the GAA20 tract and the “red” chromosome has the long GAA230 tract; both tracts are short in WXTMD42. By PCR and restriction analysis [15], we determined whether the markers (shown as X's and circles) were heterozygous or homozygous in each sector. At the top of the figure, an X indicates that the PCR fragment did not have the diagnostic restriction site, and a circle indicates that it had the site. The numbers show the approximate SGD coordinates of the marker in kb. The data from each colony are shown on a separate line. Conversion events of the 3∶1 and 4∶0 types are indicated by thin and thick lines, respectively. The color of the lines indicates whether the donated marker was from the black or red chromosomes. Green X's show RCOs that are not associated with an observable gene conversion. A. Analysis of 33 sectored colonies of WXTMD46. In this strain, many of the conversion tracts were hybrid 3∶1/4∶0 events. In some of these events (marked with an asterisk), there was a crossover within the conversion tract. An example of one of these events is shown in Figure S1. Although most of the conversion events involve donating information from the black chromosome to the red chromosome, there were two conversions in which the transfer of information occurred in the opposite direction. There was also one example of a conversion event that was separated from the crossover by markers not involved in the conversion (shown as a green X connected to the conversion event by a dotted line). B. Analysis of 18 sectored colonies of WXTMD42. In this strain, as expected, the conversion and crossover events are distributed throughout the 120 kb interval between CEN5 and the can1-100/SUP4-o markers. The rates of RCOs with 95% confidence limits, based on an average of the number of sectored colonies in at least 20 cultures, are shown in Table 1. Strains homozygous for (GAA)20 or (TTC)20 tracts (WXTMD42 and WXTMD40) had rates of RCOs of about 4×10−6/division. These rates are very similar to that observed in the isogenic PSL101 strain (6×10−6) that had no GAA•TTC tracts [15]. The strains homozygous for either the (GAA)230 or (TTC)230 tracts (WXTMD43 and WXTMD41, respectively) had RCO rates of about 2×10−4/division. Thus, the addition of a GAA•TTC tract that is only 690 base pairs in length elevated the rate of RCOs in a 120 kb interval by more than 30-fold. The strains heterozygous for the long tracts (WXTMD46 and WXTMD45) also had substantially (20-fold) elevated rates of RCOs; the rates of RCOs in the heterozygous strain were about half those observed in the homozygous strains, indicating the GAA•TTC sequences on the two homologues functioned independently. As found previously for the MD506 and MD508 strains, the orientation of the GAA•TTC tract has no strong effect on its recombinogenic properties. It should be noted that Break-Induced Replication (BIR) [12] and local gene conversion events can generate unsectored canavanine-resistant colonies; however, these colonies cannot be unambiguously distinguished from RCOs that occur prior to plating cells on canavanine-containing medium [16].

Mapping of crossovers and associated gene conversion events associated with (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts

From the results described above, one obvious possibility is that (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts are preferred sites for formation of a DSB or some other type of recombinogenic DNA lesion. By this model, one would expect most of the tract-stimulated recombination events to map at or near the position of the tract. In addition, in meiotic and mitotic recombination events in yeast analyzed previously, if a diploid is heterozygous for a preferred site of DSB formation, the chromosome with the preferred site is the recipient of genetic information in a gene conversion event [12]. We examined the positions of crossovers and associated gene conversion events in two strains: WXTMD46 (a diploid heterozygous for a (GAA)230 tract) and WXTMD42 (a diploid homozygous for [GAA]20 tracts).

The positions of the crossovers and gene conversion events were mapped by the methods described previously [15]. In brief, using PCR and restriction analysis, for both sectors of a CanR red/white sectored colony, we determined whether polymorphic sites on chromosome V were homozygous for the PSL2 form of the polymorphism (shown in red in Figure 4), the PSL5 form of the polymorphism (shown in black in Figure 4), or were heterozygous. In the previous studies of spontaneous or gamma-ray-induced mitotic crossovers, four types of sectored colonies were commonly observed: 1) RCOs unassociated with an adjacent gene conversion tract, 2) RCOs associated with an adjacent 3∶1 tract (as defined in Figure 2), 3) RCOs associated with an adjacent 4∶0 tract, and 4) RCOs associated with a hybrid 3∶1/4∶0 tract. Spontaneous recombination events are distributed throughout the 120 kb interval with a minor “hotspot” located near the can1-100/SUP4-o marker and a minor “coldspot” near CEN5 [15].

A summary of the mapping of crossovers and associated conversions in WXTMD46 is shown in Figure 4A. All markers proximal to the crossover are heterozygous in both red and white sectors, and homozygous distal to the crossover in both sectors (as illustrated in Figure 2). As observed for spontaneous events previously, most of the crossovers (29 of 33) were associated with conversion tracts of various sizes. 3∶1 and 4∶0 conversion tracts (as defined in the Introduction) are indicated by thin and thick vertical lines in Figure 4, respectively. 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts are shown by adjacent thick and thin lines. Conversion tracts shown in black indicate that genetic information was transferred from the PSL5-related homologue and red tracts show transfer of information from the PSL2-related homologue.

Almost all of the conversion events in WXTMD46 included one or both of the markers flanking the GAA•TTC tract, as expected if the recombination event initiated within the tract. All four of the crossovers unassociated with conversion (shown as green Xs) occurred in the region containing the tract. In Figure 5, we compare the distribution of conversion events in WXTMD46 and PSL101 (an isogenic diploid without a GAA•TTC tract; data from Lee et al. [15]). The difference in the distributions of conversion events in the two strains is evident. In addition, in WXTMD46, the conversion tracts were strongly biased in the direction that represents transfer of information from the PSL5-related homologue. This result is consistent with the recombinogenic lesion occurring on the PSL2-related homologue that contains the (GAA)230 tract rather than the chromosome with the (GAA)20 tract.

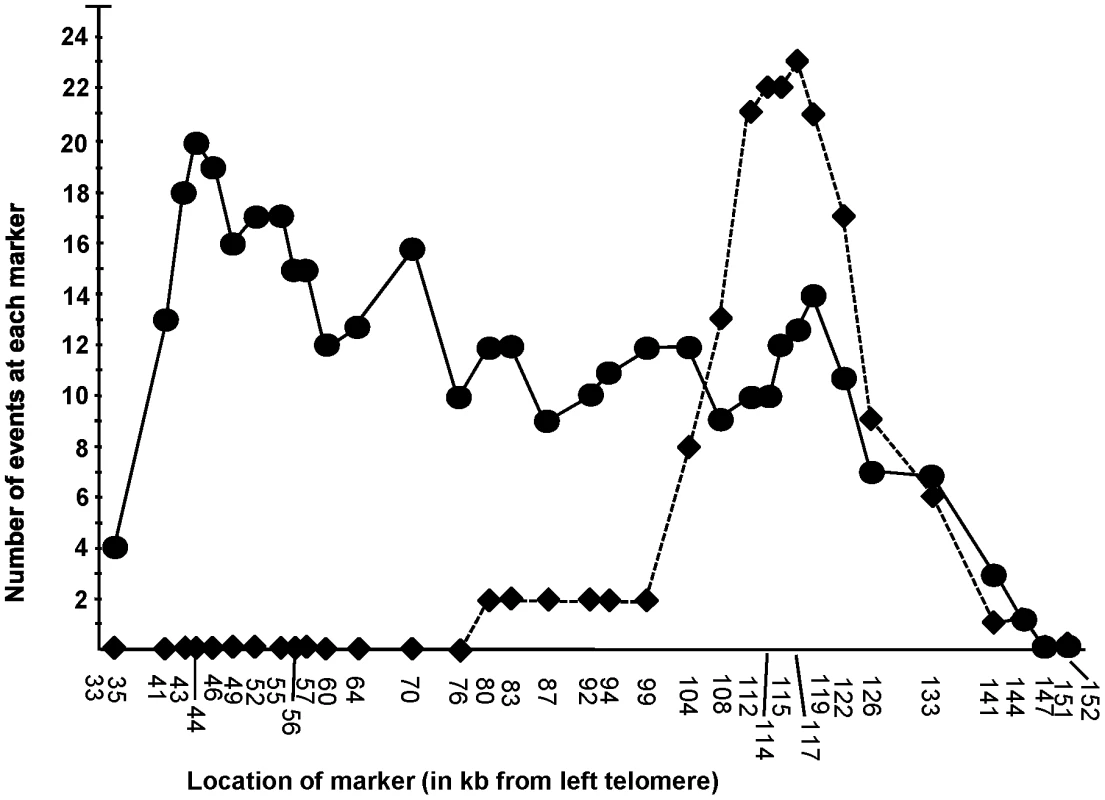

Fig. 5. Comparison of the distribution of mitotic gene conversion events in PSL100/PSL101 (lacking the (GAA)n tract) and WXTMD46 (containing the (GAA)230 tract).

For each heterozygous marker, we show the number of events that include that marker in PSL100/PSL101 (circles connected by undotted lines) and WXTMD46 (diamonds connected by dotted lines). The conversion events in PSL100/PSL101 occurred throughout the 120 kb interval with an elevation of events near markers 43 and 44, and a reduction in conversion near the centromere. In WXTMD46, the events are strongly biased toward the position of the GAA tract between markers 115 and 117. Several other features of the conversion events are important. First, most of the conversion tracts were either 4∶0 tracts or hybrid 3∶1/4∶0 tracts. As discussed previously, such tracts are most simply interpreted as representing repair in G2 of a DSB formed in G1 (Figure 2B and 2C). This issue will be discussed in more detail below. Second, although some of the observed conversion events extended symmetrically to both sides of the tract, others were asymmetric. Thus, conversion events can extend either unidirectionally or bidirectionally from the initiating DNA lesion. Third, as observed with spontaneous recombination events and events induced by gamma rays in G1 [15], [17], the conversion tracts were long compared to those observed in meiosis. We estimated tract length by averaging the minimal tract length (the distance between the markers included in the tract) and the maximal tract length (the distance between the closest flanking markers not included in the tract). The median length of the tracts was 20.3 kb (95% confidence limits of 12.5–23.4 kb), somewhat larger than the length observed in spontaneous events without the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts (6.5 kb; [15]). The median size of meiotic conversion tract lengths is about 2 kb [14]. Fourth, as in previous studies, we found a number of examples of crossovers within a conversion tract; these events are indicated by asterisks in Figure 4. As discussed in Lee et al. [15], most of these events are explicable as representing the independent repair of two broken chromatids. An example of this class of conversion event is shown in Figure S1.

We also mapped a small number of RCOs in WXTMD42, the strain homozygous for the (GAA)20 tracts (Figure 4B). As expected, these events were distributed throughout the CEN5 to can1-100/SUP4-o interval. In addition, the conversion events involved transfer of information from both homologues with approximately the same frequency. The median conversion tract length in WXTMD42 is 11.6 kb (95% confidence limits of 3.7–22.3 kb).

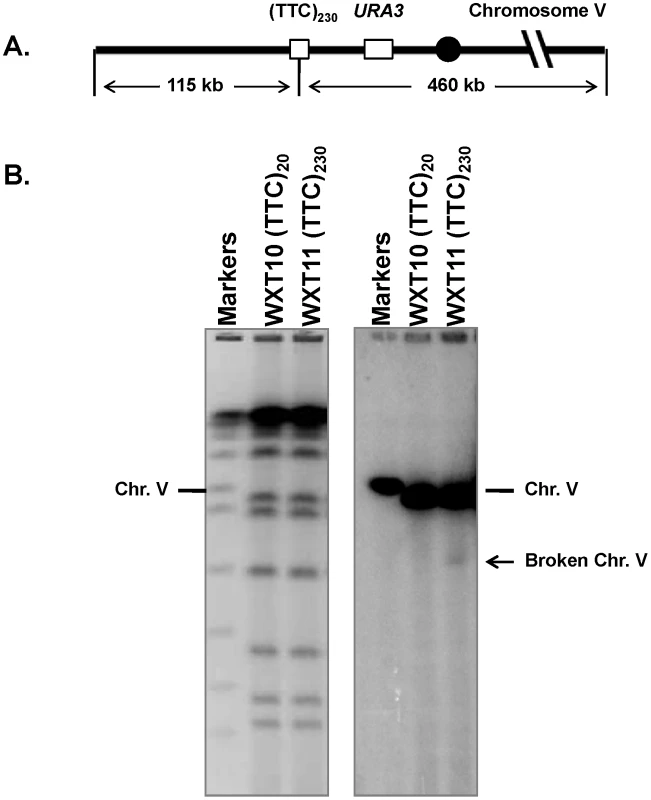

Physical evidence for DSBs associated with (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts in stationary phase cells

The genetic evidence predicts the existence of a tract-associated DSB in G1 diploid cells. To look for such DSBs directly, we prepared DNA samples from stationary phase cells (>95% unbudded cells) of two isogenic haploid strains, WXT10 with a (TTC)20 tract and WXT11 with a (TTC)230 tract. Intact chromosomal DNA was isolated from cells suspended in agarose plugs to prevent shearing and the resulting samples were analyzed by contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophoresis (CHEF gels; [25]). The separated chromosomal DNA molecules were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized to URA3-specific probe. We observed a chromosomal fragment at the position expected for a DSB within the tract (Figure 6A) in WXT11, but not in WXT10 (Figure 6B). The fraction of broken chromosomal molecules observed in three independent experiments was about 0.013 (average of 0.013, 0.017, and 0.01). Although this frequency of DSBs is considerably higher than the observed frequency of RCOs (about 10−4), it is likely that many of the DSBs are repaired by pathways, such as BIR and gene conversion unassociated with RCOs, that do not generate RCOs [12].

Fig. 6. Physical detection of tract-associated DSBs in stationary-phase (G1/G0) haploid cells.

Haploid strains with short (WXT10, 20 repeats) or long (WXT11, 230 repeats) were grown to stationary phase in rich medium. Chromosomal DNA molecules were separated by contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophoresis (CHEF gels) and Southern analysis was performed using a URA3-specific hybridization probe. A. Location of the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts on chromosome V. Based on the location, a DSB located within or near the tract should produce two chromosomal fragments, one of about 460 kb that should hybridize to a URA3-specific probe and one of about 115 kb. B. Detection of a DSB associated with the long, but not the short, tract. The left panel shows the ethidium bromide-stained gel following electrophoresis, and the right panel shows the Southern hybridization pattern of the same gel to a URA3-specific probe. Since we chose electrophoresis conditions to maximize separation of the smaller chromosomes, all 16 yeast chromosomes are not visualized as bands on the ethidium bromide-stained gels. The leftmost lane has marker DNA molecules (Biorad) isolated from a yeast strain that has chromosomes of somewhat different sizes than our strains. (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts are not strong hotspots for meiotic recombination

In yeast, long (CTG)n•(CAG)n tracts are preferred sites for DSB formation in mitosis [26]. In meiosis, long (greater than 75 repeats) (CTG)n•(CAG)n tracts were hotspots of recombination in one study [27], but were not in another [28]. Short (10-repeat) (CTG)n•(CAG)n tracts were not meiotic recombination hotspots [29].

As shown above long (GAA)n•(TTC)n promote DSB formation in mitosis. It was reasonable to ask, therefore, whether long GAA•TTC tracts stimulate meiotic recombination, as well. To address this question, we performed tetrad analysis, measuring meiotic recombination distances in three intervals on chromosome V: CEN5-ura3; ura3-can1-100/SUP4-o (the interval containing the tracts), and can1-100/SUP4-o to V9229::HYG. The heterozygous HYG gene (encoding a protein that results in resistance to hygromycin) was inserted approximately 20 kb centromere distal to the can1-100 gene. This analysis was done in WXTMD46 (which contains (GAA)230 on one homologue and (GAA)20 on the other) and PSL101 (which lacks (GAA)n•(TTC)n tract insertions). No significant differences were observed in map distances for any of the intervals (details of the analysis in Table S4). The map distance for the interval containing the insertion was 36 cM in WXTMD46 and 37 cM in PSL101 (total of about 100 tetrads examined in each strain).

Strong meiotic recombination hotspots are associated with high rates of gene conversion and crossovers [30]. The (GAA)230 tract in WXTMD46 is located about 1 kb from the mutant ura3 allele and the (GAA)20 tract is located the same distance from the wild-type URA3 allele. If the (GAA)230 tract is a preferred site for meiotic DSB formation, we would expect an elevation in gene conversion events of the 3 Ura+:1 Ura− class, since the chromosome that receives the DSB acts as a recipient for information derived from the uncut chromosome [12]. This effect should be detectable since the strong meiotic recombination HIS4 hotspot stimulates meiotic conversion events at sites located 2.7 kb from the hotspot [31], a distance longer than that between the (GAA)230 tract and URA3. In PSL101, we observed two conversion events, both 1 Ura+: 3 Ura− tetrads, in a total of 118 tetrads. In 105 tetrads derived from WXTMD46, we found no gene conversions of the 3+:1− or 1+:3− classes, but four tetrads that had 4 Ura+: 0 Ura− spores. This 4∶0 type of conversion is consistent with a mitotic gene conversion occurring within a sub-population of the WXTMD46 cells prior to sporulation [11]. Consistent with this hypothesis, in two of the tetrads with 4 Ura+ spores, all four spores had the SUP4-o marker and were HygS. These segregation patterns are consistent with a mitotic gene conversion at the ura3 locus associated with a mitotic crossover.

We also examined the meiotic stability of the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts by PCR analysis of spore DNA in 20 tetrads. Three patterns were observed. In 10 tetrads, two of the tracts were about 20 repeats in length and two were about 230 repeats in length. In 5 tetrads, two of the tracts were 20 repeats in length and two were of equal size but shorter than 230 repeats; this class is consistent with a sub-population of WXTMD46 cells in which the 230-repeat tract had undergone a mitotic deletion. In the third class (5 tetrads), two spores had 20-repeat tracts, one had a 230-repeat tract, and one had a tract of intermediate size; this class is consistent with a meiotic deletion event in one of the two 230-repeat tracts. Taken together with the mapping and gene conversion data, these results argue that the long (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts are somewhat meiotically unstable, but the DSBs formed within the tract do not strongly stimulate meiotic recombination between the homologous chromosomes. This issue will be discussed further below.

Discussion

The main conclusions from our study are: 1) (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts in both orientations strongly stimulate recombination between homologous chromosomes in mitosis, but not in meiosis, 2) the recombinogenic properties of the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts suggest that most of the events are initiated by a DSB formed in G1 of the cell cycle (a conclusion supported by a physical analysis of tract-associated DSBs), 3) the gene conversion events associated with the (GAA)n•(TTC)n repeats resemble those associated with spontaneous mitotic crossovers, and 4) single conversion events can be propagated from the location of the (GAA)n•(TTC)n insertion either unidirectionally (in either direction) or bidirectionally. Each of these conclusions will be discussed in detail below.

Mitosis-specific recombinogenic effects of (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts

Although the tendency of certain trinucleotide tracts to expand in size was first demonstrated in humans, much of the experimental research concerning the effects of genome-destabilizing effects of these sequences has been done in bacteria and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae [1], [2], [32]. In yeast, three types of repetitive trinucleotide tracts, (CTG)n•(CAG)n, (CGG)n•(CCG)n, and (GAA)n•(TTC)n, have been examined in detail. All three types of tracts undergo frequent size alterations with the frequencies of alterations increasing as a function of the number of repeats [32]. The frequency of these alterations is also affected by the orientation of the repetitive tract with respect to the replication origin. All three tracts are capable of forming secondary structures in vitro with one strand forming a more stable secondary structure than the other [1]. The orientation in which the strand with the most stable secondary structure is on the lagging strand for replication has the highest frequency of tract alterations. This orientation is also associated with replication fork pausing [1]. For the (GAA)n•(TTC)n repeats, as discussed above, replication fork pausing is observed when the (GAA)n repeats are on the lagging strand [4]. Somewhat unexpectedly, large-scale expansions of (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts occur with approximately the same frequency regardless of the orientation of the tract [6].

Since DSBs are recombinogenic [12] and since DSBs are observed at the sites of long (CTG)n•(CAG)n and (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts [5], [26], one would expect that such tracts would be hotspots for recombination. Long (CTG)n•(CAG)n tracts stimulate intrachromosomal recombination between repeats and sister-chromatid exchanges [26], [33]; long (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts elevate the frequency of recombination between repeats on non-homologous chromosomes in yeast [5] and plasmid-plasmid recombination in E. coli [7]. In these assays, it was unclear whether the recombination events were reciprocal (producing two recombined DNA molecules) or non-reciprocal. The assay used in our current study selects for reciprocal events.

We found that the 230-repeat tract elevates the rate of RCOs in 120 kb interval from about 5×10−6/division (strains with no tract or a 20-repeat tract) to about 2×10−4/division. We calculate that the rate of RCOs/kb in the strains without the tract is about 4×10−8/kb/division. The 690 bp tract has a rate of RCOs of about 3×10−4/kb/division. Consequently, the (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tract is about 104-fold more recombinogenic than an average yeast sequence.

In contrast to the strong recombinogenic effects of the tract on mitotic recombination, no strong stimulation was observed for meiotic exchange. Since we observed meiosis-specific alterations in tract length in about 25% of the tetrads that were analyzed, it is likely that the long (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts are substrates for DSB formation in meiosis. The lack of a detectable effect of the tracts on meiotic recombination can be explained in two ways. First, it is possible that tract-associated DSBs are repaired by intrachromosomal interactions (Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing, SDSA) or sister-chromatid exchanges [12]; neither of these events would be detected by standard tetrad analysis. Meiosis-specific intra-allelic changes in the lengths of minisatellites consistent with SDSA events have been observed previously in humans [34] and yeast [35], [36]. Second, it is possible that the effects of a weak tract-associated hotspot would be obscured by the very high frequency of meiosis-specific DSBs catalyzed by Spo11p. We note, however, that a strong tract-associated hotspot would have been detected by our analysis. The strong HIS4 recombination hotspot, for example, increases the map length in the LEU2-HIS4 interval from 20 cM to 36 cM [37].

Evidence that the tract-associated RCOs reflect a DSB formed in unreplicated (G1) chromosomes

Previously, we showed that about 40% of spontaneous RCOs were associated with 4∶0 or 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid conversion tracts [15]. We suggested that such events were a consequence of DSB formation on an unreplicated chromosome, followed by replication of the broken chromosome, and repair of the two resulting broken chromatids (Figure 2B and 2C). Since most of the RCOs stimulated by the (GAA)n•(TTC)n repeats are associated with 3∶1/4∶0 tracts, it is likely that the recombinogenic DSBs are formed in G1. This conclusion, based on genetic analysis, is also supported by the physical analysis demonstrating tract-associated DSBs in stationary phase cells (Figure 6). Since the DSBs occur in G1/G0, the observation that the tract-associated stimulation of RCOs is independent of the orientation of the tract is expected.

It should be emphasized that our results do not show that tract-associated DSBs occur only in G1/G0. We observed previously that (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts stimulate ectopic recombination between repeats on non-homologous chromosomes in an orientation-dependent mechanism [5]. We suggest that these events are likely to be non-reciprocal and, therefore, regulated differently than the RCOs that are the subject of the present study.

In summary, our studies of the properties of (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts indicate that they promote genetic instability by several different mechanisms. One mechanism is dependent on the orientation of the repeats and is likely to reflect breakage of replication forks [5]; this mechanism is also associated with small tract contractions/expansion and ectopic recombination events [4], [5]. A second mechanism is the orientation-independent large expansion of (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts that may involve strand-switching events in which the leading strand copies an Okazaki fragment [6]. The third mechanism is also independent of the orientation and likely reflects DSB formation in G1 to yield RCOs.

Although we have not determined the source of the G1-induced DSBs, they may reflect the action of DNA repair enzymes and/or topoisomerases interacting with secondary structures formed by the tracts. Replication-independent instability has been observed in mammalian cells for both (GAA)n•(TTC)n and (CTG)n•(CAG)n tracts [8], . This instability appears to be related to DNA repair events associated with transcription [9], [10]. In most of the strains examined in our study, the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts were embedded in a promoter-less fragment of the LYS2 gene.

Other properties of repeat-stimulated gene conversions

The most obvious difference in the patterns of spontaneous RCOs observed previously [15] and those seen in the current study is the location of the events. All of the events observed in the current study are at or near the site of the (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts, presumably because all events are initiated at or near the tracts. Although the distribution of spontaneous events observed by Lee et al. is not completely random, it is clear that the events can be initiated at many sites within the 120 kb interval (Figure 5). Although the properties of DNA sequences that regulate the probability of initiating a mitotic recombination events have not yet been completely established, mitotic recombination is promoted by closely-spaced inverted repeats [38] and by high rates of transcription [39], [40].

The median length of the tract-stimulated conversion events in WXTMD46 (20.3 kb) is longer than those observed for spontaneous events in the absence of the repetitive sequence (6.5 kb) and conversion events generated in G1-arrested cells by gamma radiation (7.3 kb; [17]). The median tract length is much longer than the median length observed associated with RCOs induced by gamma radiation in G2-arrested cells (2.7 kb; [17]).

Most of the conversion tracts are 3∶1/4∶0 hybrid tracts (Figure 4A). As discussed in the Introduction, such tracts can be explained by independent repair of two DSBs. If the DSBs occur within the GAA•TTC insertions, we expect that the 4∶0 region of the hybrid tract should include one or both of the markers flanking the tract, and this expectation is met (Figure 4A). If processing of the broken DNA ends is bidirectional and symmetric from the site of the DSB, most tracts should have a 4∶0 region flanked by 3∶1 regions. Although we observe this pattern for some of the conversion events, for other events, the 4∶0 region is at one end of the hybrid tract. Thus, we infer that the mechanism that generates the gene conversion in mitosis can be asymmetric. In addition, single conversion events can be propagated from the initiation site either toward the centromere or toward the telomere. Meiotic gene conversion tracts share these properties [41], [42].

Two different mechanisms can result in a gene conversion event. During meiotic recombination, most conversion events reflect heteroduplex formation followed by repair of any resulting mismatches. One key early intermediate in this process is a broken end that has been “processed” by 5′ to 3′ degradation on one of the two strands [13]. It is possible that mitotic conversion events involve much more extensive processing than meiotic events or extensive branch migration of the Holliday junction(s) associated with the strand invasion. An alternative possibility is that the conversion events involve the repair of a double-stranded gap [43]. Although there is strong evidence that mitotic events that generate relatively short conversion tracts are a consequence of heteroduplex formation followed by mismatch repair [44], [45], it is currently unclear whether the very long tracts are a consequence of mismatch repair or gap repair [15].

In summary, we have demonstrated that (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts strongly stimulate RCOs and our analysis indicates that these events are initiated by a DSB in unreplicated DNA. These results have several implications relevant to the genetic instability observed in patients with Friedreich's ataxia. First, a G1-associated DSB may be an intermediate in the expansion process in at least a sub-set of the expansion events. Second, since we find that the (GAA)230•(TTC)230 tracts are highly recombinogenic by a mechanism that is independent of DNA replication, our findings may be relevant to the observation that the FRDA-associated tracts are unstable in post-mitotic (non-dividing) cells and these expansions contribute to pathogenesis. For example, the highest rate of somatic instability is observed in dorsal root ganglia, which is the most damaged tissue in FRDA patients [46]. In addition, expanded (GAA)n•(TTC)n tracts may elevate the frequency of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on the chromosome containing the expanded tract, allowing heterozygous mutations to become homozygous. Since there are other (GAA)n•(TTC)n runs within mammalian genomes that are prone to expansions [47], such tracts may also promote LOH on other chromosomes. It would be of interest to examine tissues of FRDA patients or cell lines derived from patients for tract-associated DSBs (using ligation-mediated PCR) or LOH of single-nucleotide polymorphisms located centromere-distal to the expanded tracts.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains

Most of the experiments involve diploids generated by crosses of haploids with diverged DNA sequences. The haploid strain PSL5 [15] is derived from the YJM789 genetic background whereas PSL2 [15] is derived from W303a [39]. The details of the constructions and genotypes of the haploid and diploid strains are given in Text S1 and Tables S1, S2, S3. The diploids strains used to measure the effect of GAA•TTC tracts on RCOs were homozygous for the ade2-1 mutation, and heterozygous on chromosome V for can1-100 and an allelically-placed copy of SUP4-o. As described in the text, this system allows the selection of RCOs as CanR red/white sectored colonies.

Genetic analysis and Southern analyses of replication fork intermediates and tract-associated DSBs

Standard yeast procedures were used for transformations, mating, sporulation, and tetrad dissection [48]. Media were prepared as described previously [15], [16]. The two-dimensional gel analysis of replication forks was done as described previously [5]. DNA samples for the gel analysis were treated with the AflII restriction enzyme, and the Southern blot was hybridized to the 3.9 kb LYS2-specific AflII fragment isolated from pFL39LYS2 (described in Text S1). To analyze tract-associated DSBs, we grew haploid strains to stationary phase (three days of growth in rich growth medium [YPD] at 30°C), and then prepared DNA by methods described previously [25]; in the stationary-phase cultures, >95% of the cells were unbudded as expected for cells in G1/G0. Chromosomal DNA molecules were separated using the Bio-Rad CHEF Mapper XA. The Southern analysis was done using a URA3-specific probe that was prepared by PCR amplification of genomic DNA with the primers: URA3-f (5′ GGTTCTGGCGAGGTATTGGATAGTTCC) and URA3-r (5′ GCCCAGTATTCTTAACCCAACTGCAC). The hybridization signals were detected and quantitated using a PhosphorImager.

Measurements of frequencies of RCOs

The methods used to quantitate RCOs in various strains were identical to those described previously [15]. In brief, individual colonies formed on rich growth medium were suspended in water, and plated on non-selective medium (omission medium lacking arginine [SD-arg]) or on medium containing canavanine (SD-arg with 120 micrograms/ml canavanine). Plates were incubated at room temperature for four days, followed by storage for one day at 4°C (which accentuates the red color of sectors). The rate of RCOs for each strain was determined by averaging the frequency of crossovers observed in at least 20 independent cultures (colonies).

Mapping of mitotic crossovers and gene conversion events

Red and white CanR strains were purified from each half of the sectored colonies. DNA was isolated by standard procedures [48]. As we have done previously, we mapped crossovers by examining 34 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located in the 120 kb interval between CEN5 and the can1-100/SUP4-o markers. For each SNP, the DNA from one of the haploid parents contained a diagnostic restriction enzyme recognition that was altered for the other parent. For each SNP, we amplified genomic DNA using primers flanking the heterozygous marker, treated the fragment with the diagnostic restriction enzyme, and examined the products by gel electrophoresis. From this analysis, we could determine whether the sectored colony was homozygous for the YJM789 form of the SNP, homozygous for the W303a form of the SNP, or heterozygous for the polymorphism. The sequence of the primers and restriction enzymes used in the analysis are given in Lee et al. [15].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done using the VassarStats Website (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html). Most of the comparisons involved the Fisher exact test. 95% confidence limits on the rates of RCOs were calculated by determining the 95% confidence limits on the proportions (number of sectored colonies/number of colonies on non-selective plates) using the Wilson procedure with a correction for continuity. Calculations of median conversion tract lengths and 95% confidence limits on the median were done as described previously [17].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. MirkinSM

2007

Expandable DNA repeats and human disease.

Nature

447

932

940

2. KovtunIV

McMurrayCT

2008

Features of trinucleotide repeat instability in vivo.

Cell Res

18

198

213

3. CampuzanoV

MonterminiL

MoltoMD

PianeseL

CosseeM

1996

Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion.

Science

271

1423

1427

4. KrasilnikovaMM

MirkinSM

2004

Replication stalling at Friedreich's ataxia (GAA)n repeats in vivo.

Mol Cell Biol

24

2286

2295

5. KimHM

NarayananV

MieczkowskiPA

PetesTD

KrasilnikovaMM

2008

Chromosome fragility at GAA tracts in yeast depends on repeat orientation and requires mismatch repair.

Embo J

27

2896

2906

6. ShishkinAA

VoineaguI

MateraR

CherngN

ChernetBT

2009

Large-scale expansions of Friedreich's ataxia GAA repeats in yeast.

Mol Cell

35

82

92

7. NapieralaM

DereR

VetcherA

WellsRD

2004

Structure-dependent recombination hot spot activity of GAA.TTC sequences from intron 1 of the Friedreich's ataxia gene.

J Biol Chem

279

6444

6454

8. DitchS

SammarcoMC

BanerjeeA

GrabczykE

2009

Progressive GAA.TTC repeat expansion in human cell lines.

PLoS Genet

5

e1000704

doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000704

9. WangG

VasquezKM

2009

Models for chromosomal replication-independent non-B DNA structure-induced genetic instability.

Mol Carcinog

48

286

298

10. LinY

DentSY

WilsonJH

WellsRD

NapieralaM

2010

R loops stimulate genetic instability of CTG.CAG repeats.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

107

692

697

11. PetesTD

MaloneRE

SymingtonLS

1991

Recombination in yeast.

BroachJR

JonesEW

PringleJR

The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces

Cold Spring Harbor

Cold Spring Harbor Press

407

521

12. PaquesF

HaberJE

1999

Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Microbiol Mol Biol Rev

63

349

404

13. HunterN

2007

Meiotic recombination.

AguileraAA

RothsteinR

Molecular Genetics of Recombination

Berlin, Heidelberg, and New York

Springer

381

442

14. ManceraE

BourgonR

BrozziA

HuberW

SteinmetzLM

2008

High-resolution mapping of meiotic crossovers and non-crossovers in yeast.

Nature

454

479

485

15. LeePS

GreenwellPW

DominskaM

GawelM

HamiltonM

2009

A fine-structure map of spontaneous mitotic crossovers in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

PLoS Genet

5

e1000410

doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000410

16. BarberaMA

PetesTD

2006

Selection and analysis of spontaneous reciprocal mitotic cross-overs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

103

12819

12824

17. LeePS

PetesTD

2010

From the Cover: mitotic gene conversion events induced in G1-synchronized yeast cells by gamma rays are similar to spontaneous conversion events.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

107

7383

7388

18. JonesEW

FinkGR

1982

Regulation of amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis in yeast.

StrathernJN

JonesEW

BroachJR

The Molecular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces: Metabolism and Gene Expression

Cold Spring Harbor, NY

Cold Spring Harbor Press

181

299

19. ChuaP

Jinks-RobertsonS

1991

Segregation of recombinant chromatids following mitotic crossing over in yeast.

Genetics

129

359

369

20. PellicioliA

LeeSE

LuccaC

FoianiM

HaberJE

2001

Regulation of Saccharomyces Rad53 checkpoint kinase during adaptation from DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest.

Mol Cell

7

293

300

21. AylonY

LiefshitzB

KupiecM

2004

The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle.

EMBO J

23

4868

75

22. IraG

PellicioliA

BaliijaA

WangX

FioraniS

2004

DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1.

Nature

431

1011

7

23. RaghuramanMK

WinzelerEA

CollingwoodD

HuntS

WodickaL

2001

Replication dynamics of the yeast genome.

Science

294

115

121

24. MiretJJ

Pessoa-BrandaoL

LahueRS

1998

Orientation-dependent and sequence-specific expansions of CTG/CAG trinucleotide repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

95

12438

12443

25. ArguesoJL

WestmorelandJ

MieczkowskiPA

GawelM

PetesTD

2008

Double-strand breaks associated with repetitive DNA can reshape the genome.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

105

11845

11850

26. FreudenreichCH

KantrowSM

ZakianVA

1998

Expansion and length-dependent fragility of CTG repeats in yeast.

Science

279

853

856

27. JankowskiC

NasarF

NagDK

2000

Meiotic instability of CAG repeat tracts occurs by double-strand break repair in yeast.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

97

2134

2139

28. RichardG-F

CyncynatusC

DujonB

2003

Contractions and expansions of CAG/CTG trinucleotide repeats occur during ectopic gene conversion in yeast, by a MUS81-independent mechanism.

J Mol Biol

326

769

82

29. MooreH

GreenwellPW

LiuC-P

ArnheimN

PetesTD

1999

Triplet repeats form secondary structures that escape DNA repair in yeast.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

96

1504

1509

30. PetesTD

2001

Meiotic recombination hot spots and cold spots.

Nat Rev Genet

2

360

369

31. DetloffP

WhiteMA

PetesTD

1992

Analysis of a gene conversion gradient at the HIS4 locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics

132

113

123

32. LenzmeierBA

FreudenreichCH

2003

Trinucleotide repeat instability: a hairpin curve at the crossroads of replication, recombination, and repair.

Cytogenet Genome Res

100

7

24

33. NagDK

SuriM

StensonEK

2004

Both CAG repeats and inverted DNA repeats stimulate spontaneous unequal sister-chromatid exchange in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Nucleic Acids Res

32

5677

5684

34. JeffreysAJ

BarberR

BoisP

BuardJ

DubrovaYE

1999

Human minisatellites, repeat DNA instability and meiotic recombination.

Electrophoresis

20

1665

75

35. DebrauwereH

BuardJ

TessierJ

AubertD

VergnaudG

1999

Meiotic instability of human minisatellite CEB1 in yeast requires DNA double-strand breaks.

Nature Genet

23

367

71

36. BergI

CederbergH

RannugU

2000

Tetrad analysis shows that gene conversion is the major mechanism involved in mutation at the human minisatellite MS1 integrated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genet Res

75

1

12

37. FanQ

XuF

PetesTD

1995

Meiosis-specific double-strand DNA breaks at the HIS4 recombination hot spot in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: control in cis and trans.

Mol Cell Biol

15

1679

1688

38. LobachevKS

ShorBM

TranHT

TaylorW

KeenJD

1998

Factors affecting inverted repeat stimulation of recombination and deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics

148

1507

1524

39. ThomasBJ

RothsteinR

1989

Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA.

Cell

56

619

630

40. AguileraA

2002

The connection between transcription and genomic instability.

Embo J

21

195

201

41. MerkerJD

DominskaM

PetesTD

2003

Patterns of heteroduplex formation associated with the initiation of meiotic recombination in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics

165

47

63

42. JessopL

AllersT

LichtenM

2005

Infrequent co-conversion of markers flanking a meiotic recombination initiation site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics

169

1353

1367

43. Orr-WeaverTL

SzostakJW

1983

Yeast recombination: the association between double-strand gap repair and crossing-over.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

80

4417

4421

44. ClikemanJA

WheelerSL

NickoloffJA

2001

Efficient incorporation of large (>2 kb) heterologies into heteroduplex DNA: Pms1/Msh2-dependent and -independent large loop mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics

157

1481

1491

45. MitchelK

ZhangH

Welz-VoegeleC

Jinks-RobertsonS

2010

Molecular structures of crossover and noncrossover intermediates during gap repair in yeast: implications for recombination.

Mol Cell

38

211

222

46. De BiaseI

RasmussenA

MonticelliA

Al-MahdawiS

PookM

2007

Somatic instability of the expanded GAA triplet-repeat sequence in Friedreich ataxia progresses throughout life.

Genomics

90

1

5

47. ClarkRM

BhaskarSS

MiyaharaM

DalglieshGL

BidichandaniSI

2006

Expansion of GAA trinucleotide repeats in mammals.

Genomics

87

57

67

48. GuthrieC

FinkGR

1991

Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology.

San Diego

Academic Press

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Composite Effects of Polymorphisms near Multiple Regulatory Elements Create a Major-Effect QTLČlánek Horizontal Transfer, Not Duplication, Drives the Expansion of Protein Families in ProkaryotesČlánek Segregating Variation in the Polycomb Group Gene Alters the Effect of Temperature on Multiple TraitsČlánek Global Analysis of the Impact of Environmental Perturbation on -Regulation of Gene ExpressionČlánek H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone DeacetylasesČlánek A Mutation in the Gene Encoding Mitochondrial Mg Channel MRS2 Results in Demyelination in the Rat

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Scans Identifies IL18RAP, PTPN2, TAGAP, and PUS10 As Shared Risk Loci for Crohn's Disease and Celiac Disease

- Composite Effects of Polymorphisms near Multiple Regulatory Elements Create a Major-Effect QTL

- Horizontal Transfer, Not Duplication, Drives the Expansion of Protein Families in Prokaryotes

- Genome-Wide Association Study SNPs in the Human Genome Diversity Project Populations: Does Selection Affect Unlinked SNPs with Shared Trait Associations?

- Friedreich's Ataxia (GAA)•(TTC) Repeats Strongly Stimulate Mitotic Crossovers in

- Zebrafish Mutation Leads to mRNA Splicing Defect and Pituitary Lineage Expansion

- Histone H4 Lysine 12 Acetylation Regulates Telomeric Heterochromatin Plasticity in

- Bub1-Mediated Adaptation of the Spindle Checkpoint

- Segregating Variation in the Polycomb Group Gene Alters the Effect of Temperature on Multiple Traits

- Signaling Role of Fructose Mediated by FINS1/FBP in

- RNF12 Activates and Is Essential for X Chromosome Inactivation

- Comparative Study between Transcriptionally- and Translationally-Acting Adenine Riboswitches Reveals Key Differences in Riboswitch Regulatory Mechanisms

- Global Analysis of the Impact of Environmental Perturbation on -Regulation of Gene Expression

- Application of a New Method for GWAS in a Related Case/Control Sample with Known Pedigree Structure: Identification of New Loci for Nephrolithiasis

- H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

- A Mutation in the Gene Encoding Mitochondrial Mg Channel MRS2 Results in Demyelination in the Rat

- Transcription Initiation Patterns Indicate Divergent Strategies for Gene Regulation at the Chromatin Level

- The Transposon-Like Correia Elements Encode Numerous Strong Promoters and Provide a Potential New Mechanism for Phase Variation in the Meningococcus

- Proteins Encoded in Genomic Regions Associated with Immune-Mediated Disease Physically Interact and Suggest Underlying Biology

- A Novel RNA-Recognition-Motif Protein Is Required for Premeiotic G/S-Phase Transition in Rice ( L.)

- The Mucin-Like Protein OSM-8 Negatively Regulates Osmosensitive Physiology Via the Transmembrane Protein PTR-23

- Genome Sequencing and Comparative Transcriptomics of the Model Entomopathogenic Fungi and

- Rnf12—A Jack of All Trades in X Inactivation?

- Joint Genetic Analysis of Gene Expression Data with Inferred Cellular Phenotypes

- Evolutionary Conserved Regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB

- Quaking Regulates Expression through Its 3′ UTR in Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

- Evolutionary Conserved Regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB

- Rnf12—A Jack of All Trades in X Inactivation?

- Joint Genetic Analysis of Gene Expression Data with Inferred Cellular Phenotypes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání