-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaH3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

Nucleosomes in heterochromatic regions bear histone modifications that distinguish them from euchromatic nucleosomes. Among those, histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and hypoacetylation have been evolutionarily conserved and are found in both multicellular eukaryotes and single-cell model organisms such as fission yeast. In spite of numerous studies, the relative contributions of the various heterochromatic histone marks to the properties of heterochromatin remain largely undefined. Here, we report that silencing of the fission yeast mating-type cassettes, which are located in a well-characterized heterochromatic region, is hardly affected in cells lacking the H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4. We document the existence of a pathway parallel to H3K9me ensuring gene repression in the absence of Clr4 and identify a silencing factor central to this pathway, Clr5. We find that Clr5 controls gene expression at multiple chromosomal locations in addition to affecting the mating-type region. The histone deacetylase Clr6 acts in the same pathway as Clr5, at least for its effects in the mating-type region, and on a subset of other targets, notably a region recently found to be prone to neo-centromere formation. The genomic targets of Clr5 also include Ste11, a master regulator of sexual differentiation. Hence Clr5, like the multi-functional Atf1 transcription factor which also modulates chromatin structure in the mating-type region, controls sexual differentiation and genome integrity at several levels. Globally, our results point to histone deacetylases as prominent repressors of gene expression in fission yeast heterochromatin. These deacetylases can act in concert with, or independently of, the widely studied H3K9me mark to influence gene silencing at heterochromatic loci.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001268

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001268Summary

Nucleosomes in heterochromatic regions bear histone modifications that distinguish them from euchromatic nucleosomes. Among those, histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and hypoacetylation have been evolutionarily conserved and are found in both multicellular eukaryotes and single-cell model organisms such as fission yeast. In spite of numerous studies, the relative contributions of the various heterochromatic histone marks to the properties of heterochromatin remain largely undefined. Here, we report that silencing of the fission yeast mating-type cassettes, which are located in a well-characterized heterochromatic region, is hardly affected in cells lacking the H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4. We document the existence of a pathway parallel to H3K9me ensuring gene repression in the absence of Clr4 and identify a silencing factor central to this pathway, Clr5. We find that Clr5 controls gene expression at multiple chromosomal locations in addition to affecting the mating-type region. The histone deacetylase Clr6 acts in the same pathway as Clr5, at least for its effects in the mating-type region, and on a subset of other targets, notably a region recently found to be prone to neo-centromere formation. The genomic targets of Clr5 also include Ste11, a master regulator of sexual differentiation. Hence Clr5, like the multi-functional Atf1 transcription factor which also modulates chromatin structure in the mating-type region, controls sexual differentiation and genome integrity at several levels. Globally, our results point to histone deacetylases as prominent repressors of gene expression in fission yeast heterochromatin. These deacetylases can act in concert with, or independently of, the widely studied H3K9me mark to influence gene silencing at heterochromatic loci.

Introduction

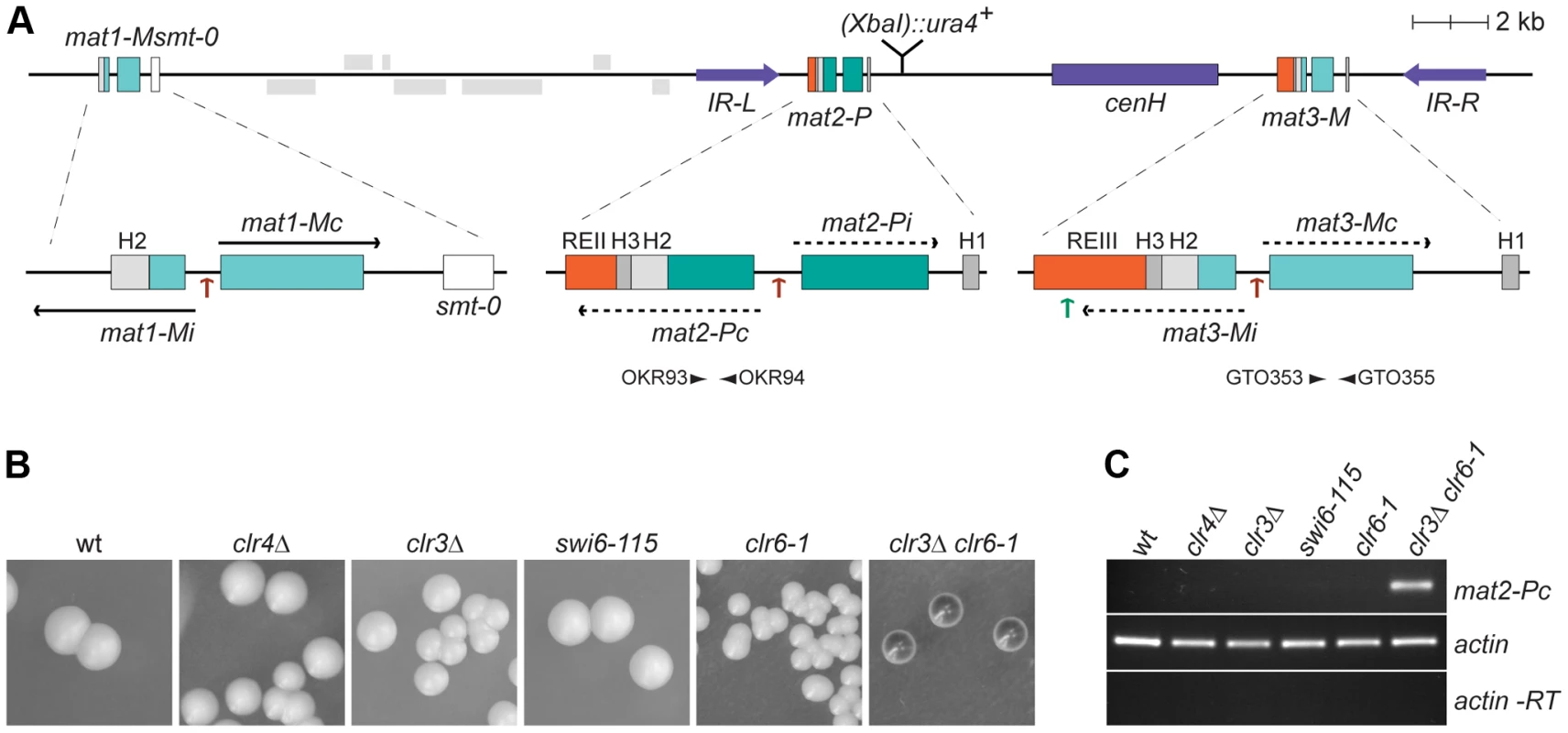

The mating-type region of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe affords a well-defined system to investigate how heterochromatic histone modifications affect gene expression [1] (Figure 1A). The region comprises three cassettes, mat1, mat2-P and mat3-M. mat1 contains and expresses either the P - or M - mating-type genes and thereby determines the mating-type of a cell. mat2-P and mat3-M contain the same genes and internal promoters of transcription as mat1, however these two cassettes are not expressed. They act as donors for gene conversions of mat1 in a process leading to mating-type switching. The tight gene silencing of mat2-P and mat3-M is essential for the viability of vegetative cells because co-expression of the P and M mating-type information triggers meiosis in starved cells [2]. P and M co-expression normally occurs only in heterozygous (mat1-P/mat1-M) diploids where it causes meiosis and sporulation, a natural process facilitating survival in harsh conditions. Co-expression of the P and M mating-type information in haploid cells on the other hand, as might happen following expression of mat2-P and mat3-M, leads to haploid meiosis and cell death [2].

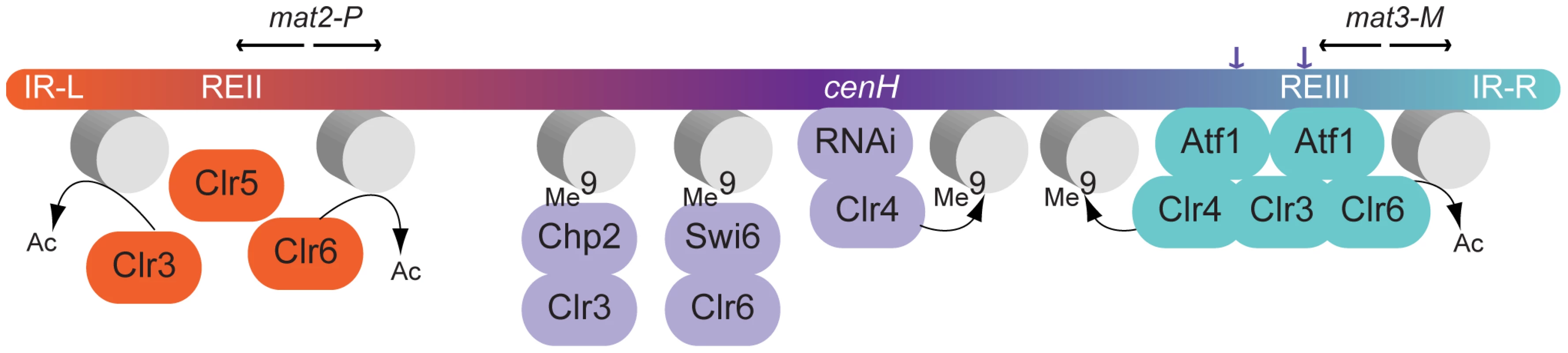

Fig. 1. Prominant role of histone deacetylation in the repression of mat2-P.

(A) Schematic representation of the mating-type region. The region between IR-L (inverted repeat left) and IR-R (inverted repeat right) is heterochromatic. Binding sites for the Ste11 transcription factor within the mating-type cassettes are indicated by brown arrows; a binding site for Atf1 in REIII is indicated by a green arrow. A second Atf1 binding site located between cenH and REIII is not represented. The smt-0 mutation prevents switching of the mat1-M cassette allowing the expression of mat2-P to be assayed by iodine staining of colonies or by RT-PCR. Primers used for RT-PCR analysis are indicated by arrowheads below mat2-P and mat3-M. REII: repressor element II; REIII: repressor element III; cenH: centromere homology. (B) Iodine staining of wild-type (PG1789), clr4Δ (SPK450), clr3Δ (PG3564), swi6-115 (SPK29), clr6-1 (SPK467) and clr3Δ clr6-1 (PG3577) strains propagated on MSA sporulation plates. Dark iodine staining is due to haploid meiosis and reflects mat2-P expression. (C) Assay of mat2-Pc transcript levels by RT-PCR. RNA was prepared from strains induced to enter the meiotic program by 5 hours of nitrogen starvation in PM-nitrogen liquid medium. The strains are as in B. Approximately 20 kb of DNA spanning mat2-P, mat3-M and the intervening K region are heterochromatic. Heterochromatin in this region is defined by H3K9me, the presence of chromodomain proteins, and hypoacetylation. Several histone deacetylases (HDACs) act in the region, in particular Clr3 and Clr6 [3], [4]. H3K9me is catalyzed by Clr4, the sole H3K9 methyltransferase in S. pombe [5]. It is bound by Clr4 itself [6] and by three other chromodomain proteins, Swi6, Chp1, and Chp2 [7]. Clr4 is a Su(var)3-9 homolog and Swi6 and Chp2 are HP1 homologs.

Numerous studies have examined the mechanisms of recruitment of Clr4 to the mating-type region. A large region between mat2-P and mat3-M, cenH, is homologous to centromeric repeats [8]. Like centromeric repeats [9], cenH produces non-coding RNAs and small interfering RNAs [10]. It has been suggested that the non-coding RNAs are capable of attracting RNA interference (RNAi) factors to the region to somehow facilitate the establishment of H3K9me [11]. RNAi however is not absolutely required for H3K9me in the mating-type region since RNAi mutants lacking an essential RNAi component like Dcr1, Ago1, or Rdp1, are not distinguishable from wild-type cells unless heterochromatin is artificially disrupted [7], [11]. Even when heterochromatin is artificially disrupted, RNAi mutants are capable of re-establishing wild-type levels of H3K9me in their mating-type region [11]. The phenotype of the RNAi mutants can be explained by a redundant recruitment of Clr4 through the CREB-like transcription factor Atf1 bound at two sites near the mat3-M cassette [12], [13]. The recruitment of Clr4 by Atf1/Pcr1 might be via a direct interaction between Clr4 and Atf1/Pcr1 [12] or it might be facilitated indirectly by histone deacetylation following the association of Clr3 and Clr6 with Atf1/Pcr1 [13], [14]. Positive feedback loops strengthen H3K9me in the mating-type region, in particular Swi6 facilitates H3K9me in the centromere-proximal half of the mating-type region that includes mat2-P [11].

Other redundancies in the silencing mechanisms operating in the mating-type region are made obvious by two classes of epistasis analyses. One class of experiments combined mutations in the HDACs Clr3 and Clr6 [3]. The second class of experiments combined cis - and trans-acting mutations. These latter experiments involve two small elements, REII and REIII, adjacent to mat2-P and mat3-M respectively (Figure 1A). When combined with a mutation in Clr4 or other mutations in the Clr4 epistasis group, deletion of either REII or REIII causes a strong expression of the adjacent cassette [15], [16], [17]. This indicates the existence of a class of factors acting redundantly with Clr4 to silence mat2-P and mat3-M through REII or REIII. We present here the first characterization of a factor in this class, Clr5.

Results

Relative contributions of H3K9me and histone deacetylation to gene silencing in the mating-type region

The mat2-P cassette contains two genes, Pi and Pc, transcribed from an internal promoter [2] (Figure 1A). Whether these genes are expressed or not can be conveniently assayed in cells containing a stable, unswitchable, mat1-M cassette (mat1-Msmt-0). Because mat1-Msmt-0 cells cannot switch to mat1-P, they form colonies containing only cells of the M mating-type that fail to mate and sporulate due to the absence of compatible mating partners of the P mating-type in the same colony. The unswitchable M colonies are not stained by iodine vapors, a stain specific for S. pombe spores. In this strain background expression of mat2-P from the normally-silenced region leads to haploid meiosis and spore formation. Hence the derepression of mat2-P can be monitored as an increase in iodine staining of mat1-Msmt-0 colonies, or by RT-PCR estimating the level of mat2-Pc transcripts in mat1-Msmt-0 cell cultures. As shown in Figure 1, the lack of Clr4 or Swi6 does not increase mat2-P expression significantly. This observation implies that the Clr4/Swi6 pathway of heterochromatin assembly is largely dispensable for the transcriptional repression of the mat2-P mating-type cassette.

Previous studies have indicated that a ura4+ reporter gene placed near mat2-P is tightly repressed in wild-type cells and derepressed by mutations in Clr4 or Swi6 [15]. However, even though it permits growth in the absence of uracil, remarkably little ura4+ transcript is present in the mutants [17]. The pronounced residual repression of ura4+ in Clr4 or Swi6 mutants is consistent with the effects observed here on mat2-Pc expression.

Unlike H3K9 methylation, several enzymes catalyze histone deacetylation redundantly. Impairing the Clr3 and Clr6 deacetylases simultaneously leads to full derepression of mat2-P evidenced by dark iodine staining of mat1-Msmt-0 colonies, high levels of haploid meiosis, and accumulation of mat2-Pc transcript (Figure 1B and 1C). This derepression shows that histone deacetylases contribute strongly to the transcriptional repression of mat2-P. In contrast, deletion of the H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4, which prevents all H9K9me accumulation, causes no detectable elevation in mat2-P expression in these assays. These data suggest that silencing factors operating redundantly with the Clr4/Swi6 pathway remain to be identified.

Genetic screen for silencing factors independent of Swi6 and Clr4

We set up a genetic screen for factors acting redundantly with Swi6 and Clr4 (Figure 2). The screen was conducted in the S. pombe strain SPK29 following insertional mutagenesis with an S. cerevisiae LEU2 gene. SPK29 cells contain the unswitchable mat1-Msmt-0 allele, an S. pombe ura4+ reporter gene near mat2-P ((XbaI)::ura4+), and a non-functional swi6 gene (swi6-115). SPK29 mutants in which mat2-P is expressed were sought by screening for colonies stained darkly by iodine vapors under conditions of nitrogen starvation. Five mutants displaying a stable dark-staining phenotype and high levels of haploid meiosis were isolated among approximately 400,000 Leu+ colonies screened.

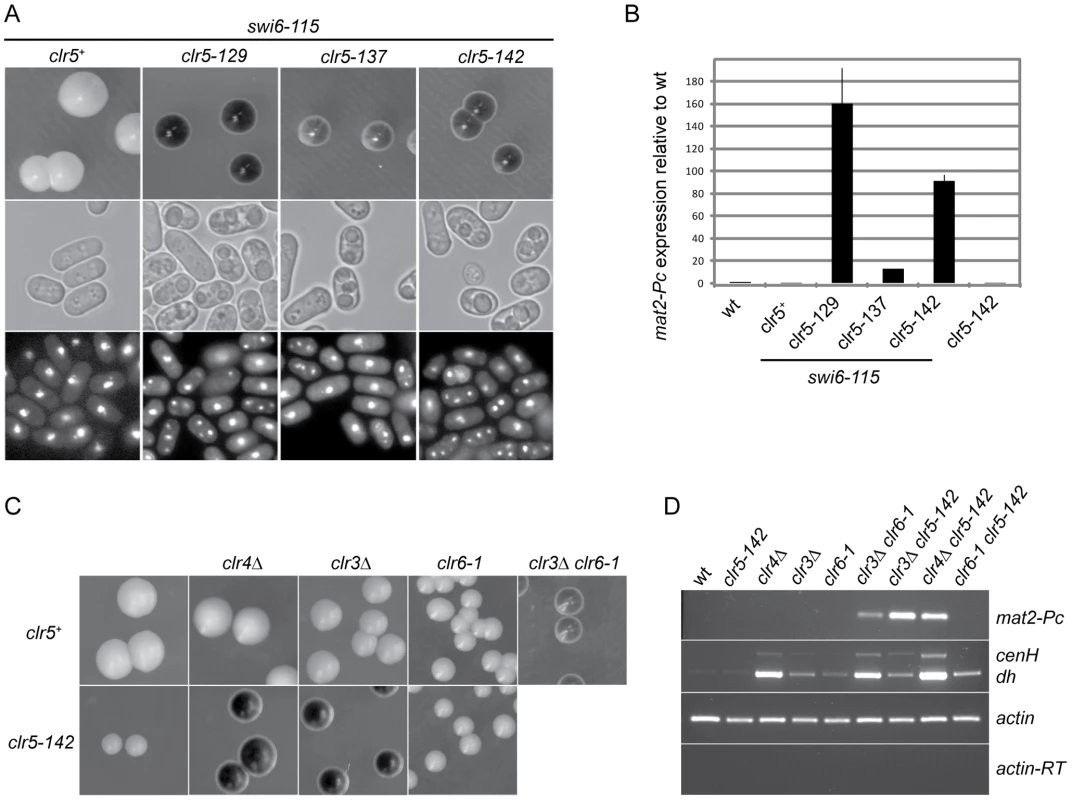

Fig. 2. Clr5 acts in the same pathway as the HDAC Clr6 and represses mat2-P independently of Swi6, Clr3, and Clr4.

(A) SKP29 and mutants obtained by insertional mutagenesis in SPK29. Colonies formed on MSA sporulation plates were stained with iodine (top panels). All strains contain the mat1-Msmt-0 cassette hence like in Figure 1 staining correlates with mat2-P expression. Cells from the same strains were imaged by DIC (middle panels) or fluorescence microscopy following DAPI staining (bottom panels). Spores are visible in DIC and as multiple DAPI-stained nuclei in clr5-129 swi6-115 (SPK129), clr5-137 swi6-115 (SPK137), and clr5-142 swi6-115 (SPK142) double mutants but not in the swi6-115 (SPK29) unmutagenized strain. (B) Real-time RT-PCR quantification of mat2-Pc transcript presented as mat2-Pc/actin ratios normalized to wild-type levels. RNA was prepared from cells propagated for 5 hours in ME. Strains from left to right: PG1789, SPK29, SPK129, SPK137, SPK142 and SPK368. (C) Epistasis analysis. mat1-Msmt-0 colonies formed on MSA sporulation plates were stained with iodine. Full derepression of mat2-P is observed when defective clr5 and clr3 or clr4 alleles are combined indicating Clr5 acts in a pathway distinct from Clr3 and Clr4. In contrast, no cumulative effect is seen when combining defective clr5 and clr6 alleles indicating Clr5 and Clr6 act in the same pathway, at least for their effects in the mating-type region. Top panel: PG1789, SPK450, PG3564, SP1240, PG3577. Bottom panel: SPK368, SPK447, SPK415, SPK493. (D) mat2-Pc and transcripts with centromere homology originating from centromeres (dh) or the mating-type region (cenH) were detected by RT-PCR using the same strains as in C. In two of the isolated mutants LEU2 was inserted in the mating-type region, in mat2-P and in its REII silencing element, respectively (SPK141 and SPK127 mutants; data not shown). Insertions disrupting REII are expected to display a cumulative effect with swi6-115 [15]. The remaining three LEU2 insertions defined a genetic locus unlinked to the mating-type region that we named clr5 (cryptic loci regulator 5; SPK129, SPK137 and SPK142 mutants; Figure 2A and 2B).

mat2-Pc is strongly derepressed in clr5::LEU2 swi6-115, clr5::LEU2 clr3Δ or clr5::LEU2 clr4Δ double mutants but not in any of the single mutants (Figure 2). These phenotypes imply that Clr5 acts upon mat2-P in a pathway different from Clr3, Swi6 and Clr4 otherwise no cumulative effects would be seen when the mutations are combined. In contrast, no cumulative effects were observed in the mating-type region when clr5::LEU2 was combined with clr6-1, suggesting Clr5 and Clr6 act in the same pathway (Figure 2C and 2D). These epistatic relationships were clearly observed when examining mat2-P transcription, and they also seemed to apply to the cenH element (Figure 2D and see below). Although centromeric transcripts were detected at the same time as cenH transcripts in Figure 2D, potential effects of Clr5 at centromeres were not investigated further.

Clr5 contains a conserved domain defining a new protein family

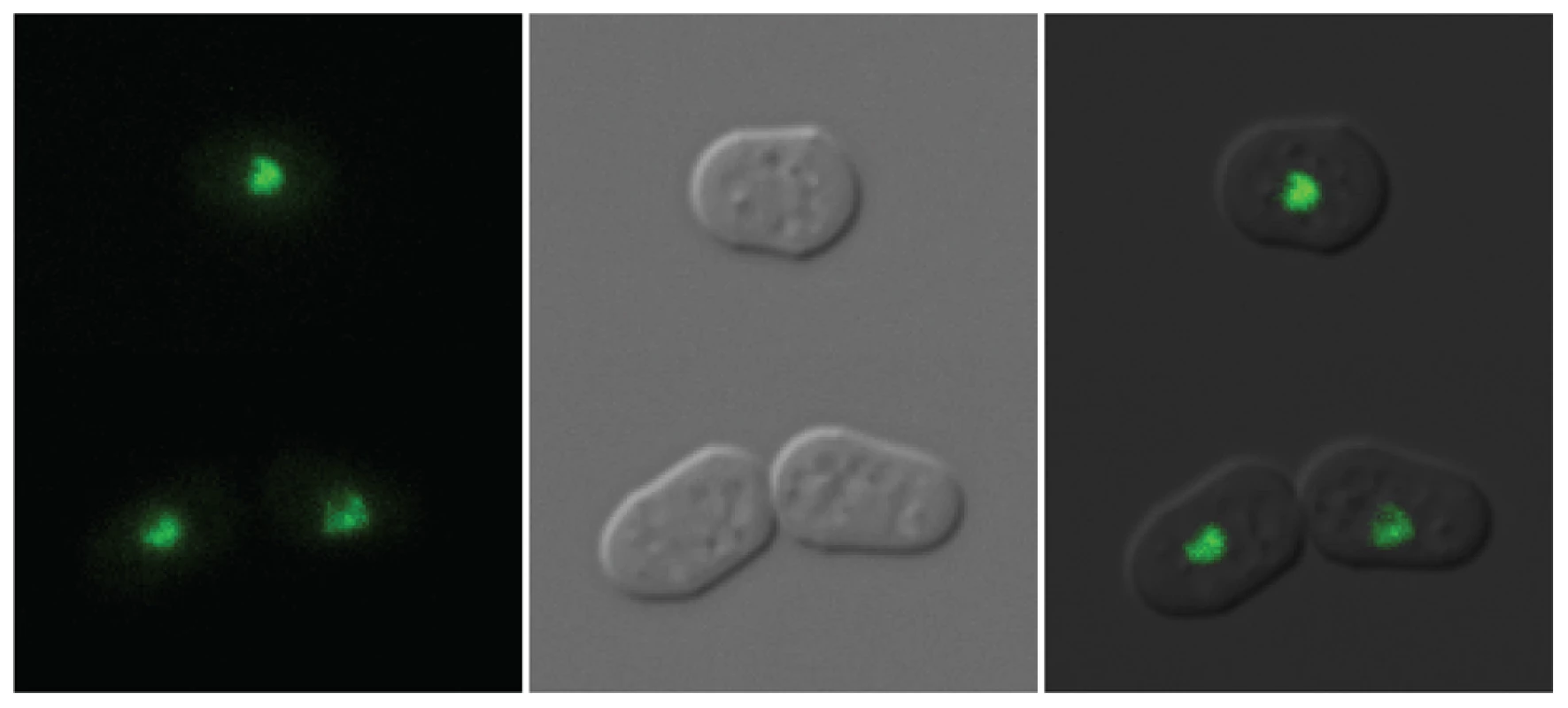

The clr5::LEU2 insertion sites in SPK129, SPK137 and SPK142 were mapped by inverse PCR identifying the clr5 locus as the predicted open reading frame (ORF) SPAC29B12.08 (see Figures S1 and S2 for details). We refined the definition of SPAC29B12.08 by experimentally mapping an intron close to the 5′ end of the gene that was missing in the original database annotations. We also identified three mutations in SPAC29B12.08 obtained in independent mutant screens for a clr5− phenotype (Figure S1). Deleting the complete clr5 ORF produced phenotypes indistinguishable from the original clr5::LEU2 insertions (see below). Clr5 tagged at its C-terminus with GFP localized predominantly in nuclear dots. It appeared to be at least partially excluded from the nucleolus (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Localization of Clr5-GFP.

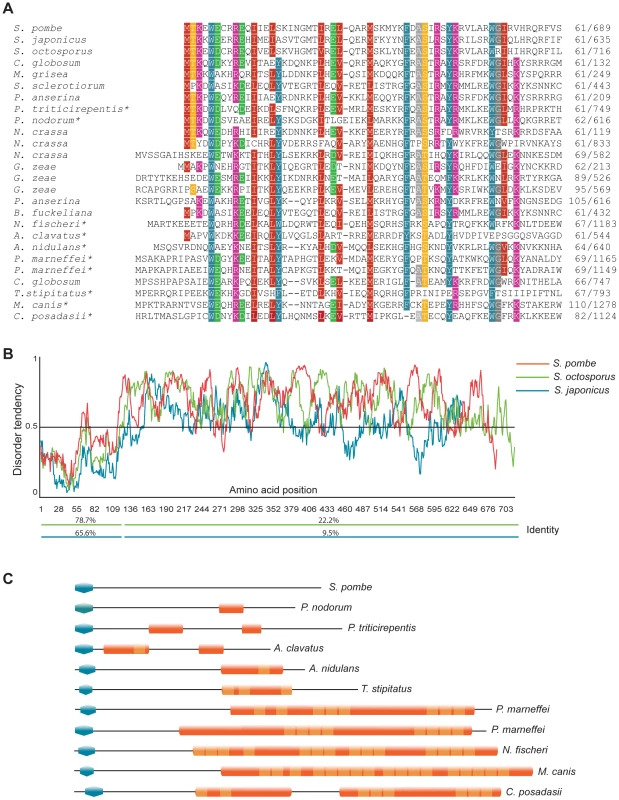

Cells were propagated in EMM2+supplements to early log phase. Clr5-GFP was expressed from the endogenous clr5 locus, under control of the clr5 promoter. The strain was FY15231. The N-terminal part of the predicted Clr5 protein contains a domain conserved in fungal species (Figure 4A). To our knowledge, this domain had not been noticed before even though >100 family members containing this domain could be identified by BLAST searches at NCBI, a few of which are displayed in Figure 4. In most cases, the domain was found close to the N-terminus of the protein. The second distinguishable feature of Clr5 is that the central and C-terminal portion of the protein display unstructured properties (Figure 4B). Comparing Clr5 with its predicted homologs in Schizosaccharomyces japonicus and Schizosaccharomyces octosporus, the closest sequenced relatives of S. pombe, we observed a much higher sequence conservation in the N-terminal part of the three proteins than in their C-terminal part as expected for structured vs. unstructured regions (Figure 4B). Many proteins with Clr5-related N-terminal domains contain unstructured regions in their C termini, like Clr5. Others contain Ankyrin repeats (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4. Features of the Clr5 protein.

(A) The N-terminus of Clr5 (first 120 amino acids) was compared to NCBI and Broad Institute databases by BLAST. Protein sequences retrieved in the searches were aligned using Multalin and manually annotated. Twenty four sequences are displayed below S. pombe Clr5, from top to bottom gi|213401369| S. japonicus; SOCG_04578 S. octosporus; gi|116202587| C. globosum; gi|145610619| M. grisea; gi|156060797| S. sclerotiorum; gi|171682396| P. anserina; gi|189207214| P. triticirepentis; gi|169619663| P. nodorum; gi|85085946| N. crassa; gi|85114724| N. crassa; gi|85092833| N. crassa; gi|46128145| G. zeae; gi|46108404| G. zeae; gi|46109918| G. zeae; gi|171689864| P. anserina; gi|154322218| B. fuckeliana; gi|119500700| N. fischeri; gi|121699656| A. clavatus; gi|67541831| A. nidulans; gi|212537897| P. marneffei; gi|212534442| P. marneffei; gi|116201027| C. globosum; gi|242812092| T.stipitatus; gi|238843722| M. canis; gi|240110365| C. posadasii. Proteins with ankyrin repeats are indicated by asterisks. (B) Disorder-tendency predictions were carried out on Clr5 and its closest homologues in S. japonicus and S. octosporus, using IUPred. The S. japonicus and S. octosporus ORFs were constructed by splicing out a predicted intron. The percentage of amino acid identities between S. pombe Clr5 and the S. japonicus (blue line) or S. octosporus (green line) proteins are indicated below the plots. (C) Schematic representation of protein domains in a subset of Clr5 family members. Blue polygons represent the N-terminal homology region between the displayed proteins and Clr5. Other domains were identified using ScanProsite [64] at http://www.expasy.ch. Orange shapes represent predicted Ankyrin repeat regions (ANK_REP_REGION, PS50297) with Ankyrin repeats (ANK_REPEAT, PS50088) shown in a lighter shade. Transcriptional signature of clr5Δ mutant

clr5 mutants display a growth defect (Figure S1) that is not simply explained by the derepression of the mating-type region but rather suggests additional targets of Clr5. In an attempt to identify these targets, we examined the transcription profile of cells lacking Clr5.

The expression profile was established in h- clr5Δ cells. The h- background is routinely used for microarray analyses i.e. [18]. In this specific case, it ensures that the variations observed between h- clr5Δ cells and the h- clr5+ control strain are not due to indirect effects through mat2-P derepression since mat2-P is lacking in h- cells.

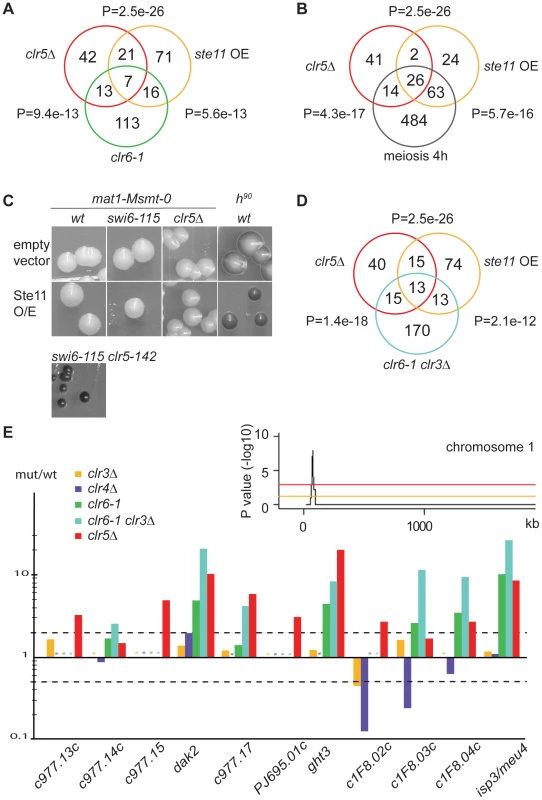

A striking overlap was observed between genes upregulated in clr5Δ cells and in cells overexpressing the master regulator of cell differentiation Ste11, or in cells in which the meiotic program had been induced (Figure 5A, 5B, and Figure S3). Ste11 is a transcription factor regulated by phosphorylation and by positive transcriptional feedback as cells respond to pheromones, prepare for mating, and undergo meiosis. In wild-type cells Ste11 activates the transcription of a series of genes involved in mating and sporulation including the two M-specific genes contained in mat1-M and the two P-specific genes contained in mat1-P. Our microarrays suggest that Ste11 itself, and possibly some of its downstream targets, are repressed by Clr5.

Fig. 5. Transcription signature of clr5Δ mutant.

(A) and (B) The list of genes upregulated >2 fold in clr5Δ cells was compared with the list of genes upregulated >2 fold in respectively clr6-1 cells [18], cells over-expressing Ste11 [65], and cells induced to undergo meiosis by 4 hours of nitrogen starvation [19]. P-values reflect the significance of gene list overlaps. (C) Over-expressing Ste11 from the pREP1-ste11 plasmid does not confer the same sporulation phenotype as deleting clr5 to a swi6-115 mutant. Sporulation was assayed on MSA medium lacking leucine and thiamine. mat1-Msmt-0 cells were PG1789 (wt); SPK29 (swi6-115); SPK464 (clr5Δ) and SPK142 (clr5-142 swi6-115). A switching-competent h90 strain was used as an additional control for sporulation, WT139. (D) As A and B but comparing with clr3Δ clr6-1 double mutant. (E) Transcriptional signature (mutant/wt ratios) of genes from a subtelomeric region of chromosome 1 (this study), [18]. Asterisks represent missing data points. Stippled lines indicate 2 fold up- or down-regulation. The inset examines the distribution of genes upregulated >2 fold in the clr5Δ mutant (average of two arrays) for part of chromosome 1, plotting the probability of the observed distribution in a 20-gene sliding window. The orange line represents a P value of 0.05 while the red line represents a P value of 0.001. The peak is a 20-gene window centered on SPAPJ695.01c (P = 1.1e−8). The fact that the same promoters of transcription are present in mat2-P and mat3-M as in respectively mat1-P and mat1-M including Ste11-binding sites (Figure 1A) raised the possibility that the increased expression of mat2-P in clr5Δ swi6-115 cells results from increased Ste11 activity in these cells. However, induction of Ste11 by nitrogen starvation in mat1-Msmt-0 swi6-115 cells (Figure 2A), or expressing Ste11 from the thiamine-regulatable nmt1 promoter in these cells (Figure 5C), did not lead to the high frequency of haploid meioses caused by clr5Δ in the same genetic background, indicating the effects of clr5Δ in the mating-type region are not simply due to derepression of Ste11.

In addition to its effects on ste11+ and downstream effectors, we found that Clr5 acts together with the Clr6 deacetylase on a number of other targets (Figure 5A). The overlapping function of Clr5 and Clr6 is fully consistent with the epistasis analysis presented above suggesting that Clr5 and Clr6 repress the mating-type region together (Figure 2A and 2D). Clr5 and Clr6 also have non-overlapping roles in gene regulation consistent with Clr6 participating in various protein complexes.

Since the Clr3 and Clr6 deacetylases act redundantly on many genes [18] we compared the expression profiles of clr5Δ and clr3Δ clr6-1 mutants (Figure 5D and 5E). This comparison identified several genes with correlated expression values. In total 28 genes were commonly upregulated in the two mutants. By analyzing the genomic distribution of these genes we found a region spanning 11 subtelomeric genes that were upregulated in clr5Δ mutants (9 of 11 genes), clr3Δ clr6-1 double mutants (7 of 11 genes) and in clr6-1 mutants (5 of 11 genes; Figure 5E). Genes in this region are also induced during the meiotic program as a response to nitrogen starvation [19], and recently this region was found to favor neo-centromere formation [20] indicative of a unusual chromatin structure.

Range of action of Clr5 in the mating-type region

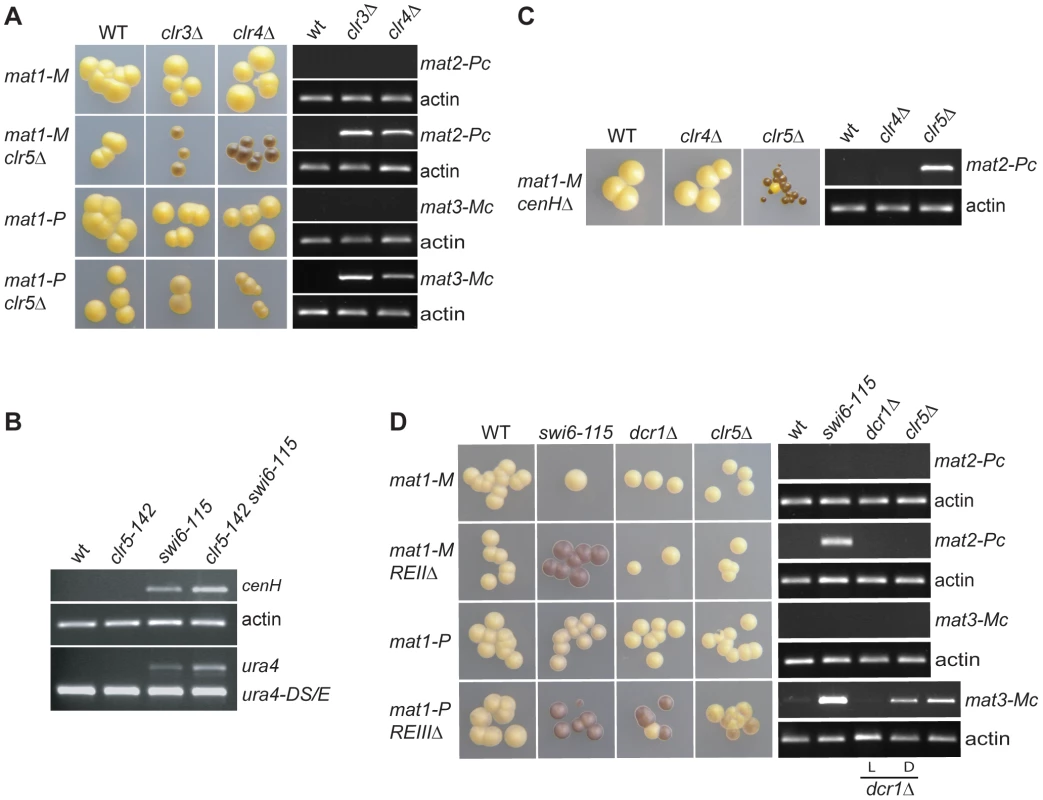

Heterochromatin spans ∼20 kb in the mating-type region. mat2-P is close to the centromere-proximal edge of the heterochromatic domain, mat3-M close to its centromere-distal edge, and ∼15 kb of heterochromatin separate the two cassettes (Figure 1A). Clr5 was identified because it represses mat2-P. We investigated whether Clr5 also represses mat3-M and/or reporter genes placed between mat2-P and mat3-M.

Whether Clr5 represses mat3-M was assayed using cells containing a stable mat1-P allele (mat1-PΔ17; Figure 6A). Expression of mat3-M was monitored in these cells by measuring haploid meiosis – driven by the co-expression of mat1-P and mat3-M - and by RT-PCR. The RT-PCR conditions we used failed to detect mat3-Mc transcripts in the clr3Δ and clr4Δ single mutants, however we observed occasional haploid meioses in clr3Δ or clr4Δ colonies indicating a low level of mat3-M transcription occurs in these mutants. In the double clr3Δ clr5Δ and clr4Δ clr5Δ mutants, both haploid meioses frequency and mat3-Mc transcript levels were increased. These effects of Clr5 at mat3-M appeared much less pronounced than the effects of Clr5 at mat2-P as judged by the iodine staining of mat1-PΔ17 clr5Δ clr3Δ (or clr4Δ) colonies compared with mat1-Msmt-0 clr5Δ clr3Δ (or clr4Δ) colonies, however the abundance of mat3-Mc transcript was clearly increased in the double mutants (Figure 6A). These observations show that Clr5 contributes to the repression of mat3-M – albeit to a comparatively low level – and that, at mat3-M like at mat2-P, repression by Clr5 is redundant with repression by Clr3 or Clr4 (Figure 6A).

Fig. 6. Range of action of Clr5 in the mating-type region.

Strains with the indicated genotypes were starved for nitrogen and examined by iodine staining of colonies and by RT-PCR to estimate the effects of Clr5 at various locations in the mating-type region in wild-type and mutant backgrounds. (A) Clr5 represses both mat2-P and mat3-M redundantly with Clr3 and Clr4. Unswitchable mat1-Msmt-0 (mat1-M) strains were used in the upper panels to assay expression of mat2-P. Unswitchable mat1-PΔ17 (mat1-P) strains were used in the lower panels to assay expression of mat3-M. mat1-M strains were: WT: PG1789; clr3Δ: PG3564; clr4Δ: SPK450; mat1-M clr5Δ strains were WT: PG3631; clr3Δ: PG3633; clr4Δ: PG3630; mat1-P strains were: WT: PG3201; clr3Δ: PG3634; clr4Δ: PG3639; mat1-P clr5Δ strains were: WT: PG3611; clr3Δ: PG3637; clr4Δ: PG3629. (B) Clr5 affects the mat2-mat3 intervening region as revealed by increased expression of cenH and (XbaI)::ura4+ in clr5-142 swi6-115 mutant (see Figure 1 for (XbaI)::ura4 localization). The strains were: WT: PG1789; clr5-142: SPK368; swi6-115: SPK29; clr5-142 swi6-115: SPK142. (C) Clr5 and cenH belong to different epistasis groups as revealed by the strong derepression of mat2-P in a cenHΔ clr5Δ double mutant. The mat1-Msmt-0 cenHΔ strains were WT: AP152; clr4Δ: AP2468; clr5Δ: AP2421. (D) Clr5 and REII belong to the same epistasis group and Clr5 and REIII to different epistasis groups. mat1-M strains were: WT: SP1125; swi6-115: SP1126; dcr1Δ: AP1661; clr5Δ: SPK464; mat1-M REIIΔ strains were: WT: SP1151; swi6-115: SP1138; dcr1Δ: SP1645; clr5Δ: AP2448; mat1-P strains were: WT: PG447; swi6-115: PG1584; dcr1Δ: AP1667; clr5Δ: AP2452; mat1-P REIIIΔ strains were: WT: PG1550; swi6-115: PG1192; dcr1Δ: AP1649; clr5Δ: AP2450. Both a repressed, light-staining (labeled L) and a derepressed, dark-staining (labeled D) dcr1Δ culture were used to prepare RNA for the RT-PCRs displayed in the two bottom panels. As mentioned above the transcriptional repression of transgenes placed in the mating-type region is alleviated in mutants belonging to the Clr4/Swi6 pathway, but the transcript levels are not as high as when the genes are transcribed from a euchromatic location [17], [21], [22]. It is therefore possible to ask whether factors of interest contribute to the repression redundantly with Clr4 or Swi6 by examining the ura4+ transcript levels in double mutants. We observed that ura4+ inserted near mat2-P (Figure 1; mat2-P(XbaI)::ura4+) was more strongly expressed in the clr5-142 swi6-115 double mutant than in either single mutant (Figure 6B and Figure S4). We also observed increased accumulation of cenH transcripts in the clr5-142 swi6-115 and clr5-142 clr4Δ double mutants (Figure 2D and Figure 6B). These widespread effects strengthen the conclusion that Clr5 does not act solely through Ste11 to activate the mating-type genes specifically.

Clr5-responsive cis-acting elements

The RNAi pathway has been proposed to recruit Clr4 to the mating-type region by acting upon non-coding transcripts generated from the cenH element. Consistent with this proposal, deletion of cenH affects H3K9me in the mating-type region. Cells lacking cenH adopt one of two semi-stable epitypes: one similar to wild type displaying normal levels of H3K9me and one similar to the clr4Δ mutant characterized by reduced H3K9me [11], [23], [24]. The fluctuations between two phenotypes can be understood in the frame of models postulating that the establishment and maintenance of heterochromatin proceed through distinct mechanisms. One such model would be that cenH facilitates the establishment of H3K9me in wild-type cells without being necessary to the subsequent maintenance of the H3K9me state. The fluctuations between two epigenetic states can be followed experimentally using reporter genes, for example replacement of cenH with ade6+ leads to variegated ade6+ expression [25]. Noticeably, mat2-P remains silent in cenHΔ::ade6+ cells regardless of the expression state of ade6+ (Figure 6C) in agreement with H3K9me being dispensable for the repression of mat2-P. Our observations with clr5Δ clr4Δ mutants suggested that combining clr5Δ with cenHΔ should lead to a cumulative derepression of mat2-P. Indeed, deleting clr5 in cenHΔ cells increased the expression of mat2-P (Figure 6C). Furthermore, as with cenHΔ single mutants, fluctuations between two phenotypes still occurred. Similarly, deleting clr5 in a dcr1Δ background released the repression of mat2-P in a variegated manner (Figure S5). We conclude from these observations that Clr5 insures a cenH/RNAi-independent silencing in the mating-type region.

We tested in a similar manner whether Clr5 exerts its effects through the REII or REIII silencing elements found near mat2-P and mat3-M respectively by combining clr5Δ with deletions of these elements. Deleting clr5 in cells lacking the mat3-M-adjacent element REIII lead to a small cumulative, variegated, derepression of mat3-M (Figure 6D) placing clr5 in a pathway different from the REIII pathway. In contrast to the situation with cenH or REIII, deleting clr5 in cells that lack REII did not increase the expression of mat2-P (Figure 6D). This supports the notion that Clr5 acts through REII, a proposition substantiated by the effects of clr5Δ on ectopic silencing reporters (see below) and by the fact that an REII insertional mutant had been obtained in the same genetic screen as the clr5::LEU2 mutants.

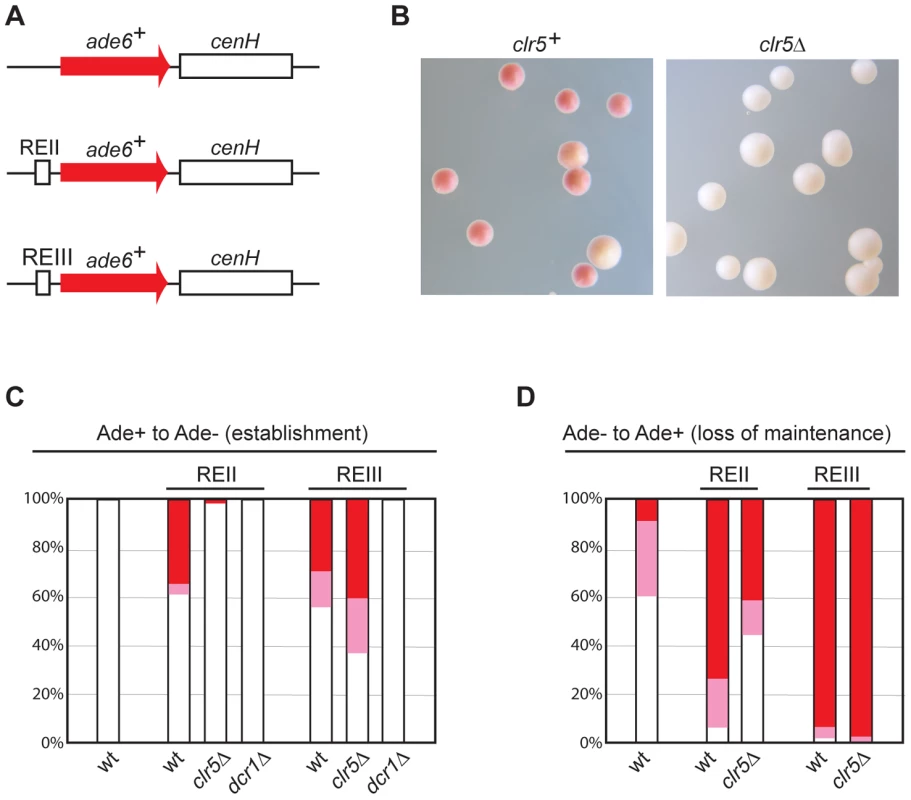

REII-mediated silencing at an ectopic site requires Clr5

To further test whether REII and Clr5 participate in the same silencing mechanism, we asked whether REII-mediated silencing at an ectopic site depends on Clr5. Insertion of a cenH sequence adjacent to an ade6+ reporter gene at an ectopic site confers partial heterochromatic silencing on ade6+ [26]. Changes in the expression state of ade6+ can be monitored at the colony level by a color test. Cells expressing ade6+ produce white colonies while cells that fail to express ade6+ produce red colonies or sectors due to the accumulation of a red byproduct in the adenine biosynthetic pathway. Hence, establishment of silencing can be monitored as a change from white to red and loss of silencing as a change from red to white. Silencing of ade6+-cenH is established at a very low rate, but it is epigenetically maintained for several generations. Rates of establishment and stability of silencing are markedly enhanced by inserting REII [26] (Figure 7) or REIII (Figure 7) adjacent to the ade6+-cenH construct.

Fig. 7. Clr5 mediates gene silencing at an ectopic site in an REII-dependent manner.

(A) Schematic representation of constructs inserted at the ura4 locus to monitor the effects of cenH, REII, REIII, and selected trans-acting factors on ectopic silencing. (B)–(D) Silencing of the REII-ade6+-cenH ectopic construct depends on Clr5. (B) clr5+ and clr5Δ strains with REII-ade6+-cenH were propagated on plates poor in adenine (AA with 15 mg/l adenine). On these plates, cells in which REII-ade6+-cenH is repressed form red or pink colonies and cells in which REII-ade6+-cenH is expressed form white colonies. Cells from white (C) or red (D) colonies were replated on medium with a low adenine concentration and white, pink, and red colonies were counted, hereby determining the proportion of cells that had changed their epigenetic state. At least 200 colonies were counted on each plate. The ade6+-cenH WT strain was AP2374; the REII-ade6+-cenH strains (marked REII) were: WT: AP270; clr5Δ: AP2354; dcr1Δ: AP2403; the REIII-ade6+-cenH strains (marked REIII) were: WT: AP1665; clr5Δ: AP2346; dcr1Δ: AP2406. We examined whether ade6+ silencing in strains where the ectopic ade6+-cenH construct was fused to either REII or REIII depends on Clr5 or Dcr1. Consistent with cenH-mediated silencing relying on RNAi, deletion of dcr1 abolished silencing in both strains (Figure 7). In contrast, deletion of clr5 affected silencing of the REII-ade6+-cenH construct, but not silencing of the REIII-ade6+-cenH construct (Figure 7). Hence Clr5 participates specifically in REII-mediated silencing at the ectopic site.

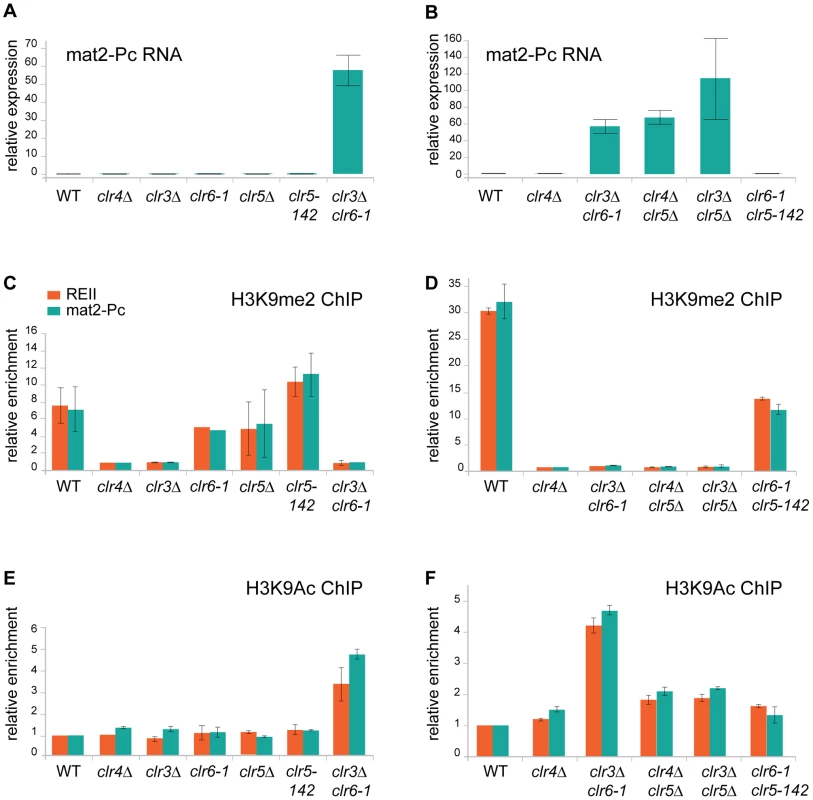

Histone modifications in clr5 mutants

The genetic interactions between clr5, clr3, clr6, and clr4 suggested the chromatin structure of the mating-type region might change in some of the double mutants, accounting for changes in gene expression. Hence, H3K9 methylation (H3K9me2) and acetylation (H3K9Ac) were examined at the REII element and mat2-P in single and double mutants (Figure 8). The expression of mat2-Pc was measured in the same strains (Figure 8A and 8B). This experiment gave the following insights in the molecular mechanisms responsible for the effects observed in the various mutants.

Fig. 8. Chromatin modifications and mat2-Pc expression in clr5 mutants.

(A) and (B) mat2-Pc RNA levels in various mutants. RNA was prepared from cells starved for nitrogen for 5 hr to induce expression of the mating-type genes. Changes in mat2-Pc expression relative to wild-type (PG1789) were estimated by real-time PCR and plotted, using actin for normalization. The means of two biological experiments are displayed. Strains analyzed in (A) were WT: PG1789; clr4Δ: SPK450; clr3Δ: PG3564; clr6-1: SP1240; clr5Δ: PG3631; clr5-142: SPK368; and clr3Δ clr6-1: PG3577. Strains analyzed in (B) were WT: PG1789; clr4Δ: SPK450; clr3Δ clr6-1: PG3577; clr4Δ clr5Δ: PG3630; clr3Δ clr5Δ: PG3633; clr6-1 clr5-142: SPK493. (C) and (D) Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of H3K9me2 at the REII and mat2-Pc locus of the mating-type region compared with the adh1+ locus measured by real-time PCR. Enrichment of H3K9me2 was normalized to the values derived for a strain that lacks H3K9me2 (clr4Δ, SPK450). Values represent the means of two independent ChIP experiments except for clr6-1 mutant were only one ChIP experiment is shown. Strains analyzed in (C) were as in (A). Strains analyzed in (D) were as in (B). (E) and (F) Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of H3K9Ac at the REII and mat2-Pc locus of the mating-type region compared with the adh1+ locus measured by real-time PCR. Values were normalized to the wild-type strain (PG1789) and represent the means of two independent ChIP experiments. Strains analyzed in (E) were as in (A). Strains analyzed in (F) were as in (B). First, as predicted from the phenotypic analysis described above, lack of H3K9me2 is not sufficient to derepress mat2-P. This could be seen in the clr3Δ and clr4Δ mutants, both of which lacked H3K9me2 at REII and mat2-P, yet failed to express mat2-Pc to a detectable level (Figure 8A and 8C). Deletion of clr5 in either of these strain backgrounds lead to a>50 fold increase in mat2-Pc expression indicating Clr5 is necessary for the H3K9me-independent repression of mat2-Pc in clr4Δ and clr3Δ cells (Figure 8B and 8D), a result also corroborating our genetic analysis. Clr5 itself showed no sign of directly affecting H3K9me2, the level of H3K9me in clr5Δ or clr5-142 was not significantly different from wild-type (Figure 8C; please note that clr5-142 is in all likelihood a loss of function allele due to LEU2 insertion at the beginning of the gene. No clr5 transcripts were detected in clr5-142 cells (Figure S1).

Changes in H3K9Ac were also observed at REII and mat2-P in the various mutants examined. The greatest increase in H3K9Ac occurred in the clr3Δ clr6-1 double mutant consistent with the two HDACs acting redundantly on this substrate. Furthermore H3K9Ac increased in the clr4Δ clr5Δ and clr3Δ clr5Δ double mutants relative to each single mutant (which were not significantly different from wild-type) supporting the idea that Clr5 acts together with an HDAC. One should bear in mind when interpreting these data that histone deacetylases tend to be promiscuous affecting more than one of the numerous nucleosomal lysines that are subject to acetylation and they might furthermore deacetylate proteins other than histones hence changes other than H3K9Ac might take place in the mutants we examined and also affect gene expression.

Finally, only strains with both abnormally low H3K9me and abnormally high H3K9ac expressed mat2-Pc. These were the clr4Δ clr5Δ, clr3Δ clr5Δand clr3Δ clr6-1 double mutants. Strains lacking H3K9me but showing no increase in H3K9Ac (clr3Δ and clr4Δ) failed to express mat2-P. Conversely, a small increase in H3K9Ac that was not accompanied by loss of H3K9me in the clr6-1 clr5Δ double mutant did not lead to mat2-P expression. These results epitomize the redundancy of silencing mechanisms at the mat2-P cassette.

Discussion

The mechanisms by which H3K9me is brought about in defined chromosomal regions of fission yeast have been extensively studied in the last decade. Perhaps because of this widespread interest, H3K9me tends to be equated with heterochromatin while histone deacetylation in the same regions has often been presented as a simple pre-requisite for H3K9me. Recent studies have proposed an additional, more direct, role of histone deacetylation in heterochromatic gene silencing [14], [27]–[30]. However, this role has been discussed exclusively in the context of H3K9me, that is, histone deacetylation has been presented only as a facilitating factor for, or consequence of, H3K9me. Arguing against these widespread views we found that some essential properties of heterochromatin are largely independent of H3K9me and rely instead on deacetylation and on a hitherto uncharacterized factor, Clr5. These H9K9me-independent mechanisms of repression act in parallel and/or cooperate with H3K9me-dependent mechanisms to ensure a very tight repression of the mating-type genes in S. pombe.

mRNA and histone modification profiling have revealed that HDACs have a broad impact on global gene expression in fission yeast [18], [31]–[33]. The experiments presented here document critical effects of HDACs at the silent mating-type cassettes as well. mat2-P and mat3-M are tightly repressed by heterochromatin in wild-type cells. Their repression was largely retained in cells lacking Clr4 (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 6, Figure 8; data not shown) showing H3K9me is not necessary for silencing. Repression was much more strongly affected in the double clr3Δ clr6-1 HDAC mutant. Histone acetylation, examined at mat2-P, was as expected increased in the clr3Δ clr6-1 mutant correlating with mat2-P expression (Figure 8). Whether increased acetylation was the sole cause for derepression of the mating-type region in the clr3Δ clr6-1 mutant is unclear since this mutant also lacked H3K9me at mat2-P (Figure 8D) leaving open the possibility that loss of silencing results from a combination of increased acetylation and reduced H3K9me. More generally full expression of mat2-P was observed only in mutants lacking both a H3K9me pathway component (Swi6, Clr3 or Clr4) and a component belonging to the REII/Clr6/Clr5 epistasis group (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 6, Figure 8) highlighting the redundancies and cross-talks which take place between deacetylation and H3K9me pathways to elicit full silencing in the mating-type region. Relatively little is known regarding the mechanisms by which histone modifications facilitate or inhibit gene expression in any eukaryote. In fission yeast, Clr3 preferentially deacetylates H3K14ac and Clr6 deacetylates several lysines of histone H3 and H4 [4]. Both enzymes repress transcription by limiting the access of Pol II to heterochromatin [14], [27]–[30]. The H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 has also been reported to restrict Pol II access to heterochromatin [34]. This might be through a direct effect of H3K9me, or it might be through the ability of Clr4 to indirectly recruit HDACs. Clr3 fails to associate with mat2-P in swi6 mutants [14] suggesting it also fails to associate with mat2-P in clr4Δ mutants. Other studies indicate the chromodomain protein Chp2 bound to H3K9me recruits the Clr3-containing complex SHREC while Swi6 recruits the Clr6-containing complex Clr6 CII [28]–[30]. HDACs and HMTs are found in complexes in higher eukaryotes and HP1, like Swi6 or Chp2 in S. pombe, can bridge H3K9me with HDACs [35], [36] indicating transcriptional repression by H3K9me might generally occur through the action of HDACs. In the present case, the ability of Clr4 to indirectly recruit HDACs might account for its redundant effects with Clr5.

Genes placed in heterochromatic regions can remain sensitive to transcriptional activation. For example in S. cerevisiae, a URA3 gene inserted near a telomere is silenced by the Sir proteins and histone deacetylation but its expression can be stimulated by increased levels of Ppr1, a transcriptional activator of URA3 [37]. Similarly, lack of Ppr1 increases URA3 silencing at the silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae mutants partially deficient for silencing [38] By analogy, increased expression of the ste11+ gene in clr5Δ mutants suggests a mechanism for the high haploid meiosis observed in for example clr5Δ clr4Δ mutants. Namely, the loss of H3K9 methylation combined with the presence of an activated transcription factor increases transcriptional activity at the normally-silent mating-type cassettes. Arguing against this simple model, we found that overexpressing ste11+ in swi6-115 cells starved for nitrogen does not lead to high levels of haploid meiosis (Figure 5C), indicating the effects of clr5Δ in the mating-type region are not solely due to increased ste11+ expression in this mutant. Our data do not exclude more complex models where down-regulation of the ste11+ gene or of the Ste11 protein activity by Clr5 would contribute to silencing in the mating-type region.

Our observations expand current models for silencing in the mating-type region (Figure 9). We propose that Clr5 and deacetylation – of histones and possibly other as-yet-unidentified substrates of Clr3 or Clr6 - repress mat2-P via the REII element. Independently, deacetylation would proceed from Atf1-binding sites near mat3-M as proposed by others [12], [13] and perhaps through some other DNA element in REIII distinct from the Atf1-binding sites [16]. The effects of Clr5 and Atf1 would not be strictly local, however each factor would predominantly affect the region close to its cognate cis-acting element. H3K9me spreading from the cenH nucleation site would further facilitate deacetylation and gene repression throughout the region [14], [28]–[30]. Even in the absence of Clr4 and H3K9me, a substantial repression would be achieved, sufficient to prevent haploid cells from undergoing meiosis.

Fig. 9. Model for gene silencing in the mating-type region.

Both Clr5 and Atf1 repress gene expression by promoting deacetylation in their respective target regions, Clr5 directly or indirectly via the REII element (this study), and Atf1 via Atf1-binding sites near mat3-M [12], [13]. The effects of Clr5 and Atf1 gradually decrease as the distance from their respective cis-acting element increases. An additional layer of silencing is orchestrated by Clr4. Clr4 can be recruited by direct binding to Atf1 [12] or through the RNAi-dependent cenH nucleation site [11]. H3K9me catalyzed by Clr4 permits binding of the chromodomain proteins Swi6 and Chp2 and spreading of histone deacetylation [14], [28]–[30]. Inactivation of both the Clr4 and Clr5 pathways is required for mat2-P expression. While the clr4Δ clr5Δ combination derepresses mat2-P (this study), this is not the case for the clr4Δ clr6-1 combination [3]. To account for these different phenotypes, we suggest that Clr3 can partially substitute for Clr6 in a Clr5-dependent manner. It has previously been proposed that REII and REIII might be transposon remnants capable of mediating silencing in cis like LTRs do in the case of retrotransposons, through histone deacetylation [39]. Our data suggest that the function of Clr5 at REII might be evolutionarily comparable to the function of Atf1 at REIII. Clr5 and Atf1 are functionally related in several other ways. In addition to being both required for transcriptional repression in the mating-type region [12], [13] (this study) both Atf1 and Clr5 regulate ste11+ [40] (Figure 5). Through these points of action, both factors prevent untimely meiosis. Atf1 is responsible for other chromatin-mediated effects unrelated to transcription for example effects on recombination and transposition [41], [42]. Similarly, Clr5 has other functions than those described here such as a role in DNA repair suggested by the hypersensitivity of clr5Δ cells to DNA-damaging agents [43]. This role in the resistance to DNA damage might be performed together with Clr6, like gene repression, since clr6-1 mutants are also sensitive to DNA-damaging agents [44]. Clr5 might furthermore affect genome integrity through its control of a large region prone to neo-centromere formation [20] (Figure 5). Unlike Atf1, Clr5 does not belong to a well-described family of transcription factors, however all known characteristics of Clr5 are compatible with a role in chromatin organization and transcription. For instance Clr5 localizes to the nucleus, the transcription profile of the clr5 mutant is consistent with Clr5 regulating transcription through deacetylation, and the predicted physical characteristics of Clr5 are also compatible with a role in transcription.

The Clr5 protein is predicted to contain a large disordered region. Intrinsically unstructured proteins (IUPs) are a large group of proteins that lack well-defined secondary and tertiary structures, (reviewed in [45], [46]). Many IUPs interact with other proteins via their disordered region, which has been proposed to undergo induced folding upon interaction with a binding partner [46]. Transcription factors are abundant among IUPs for example Jun, p53, Myb, and CREB contain unstructured domains. Similar to histone tails, their disordered nature allows access for various covalent modifications such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation, facilitating the concomitant folding and interaction with binding partners.

In addition to its large predicted disordered region the Clr5 protein contains a hitherto undescribed domain in its N-terminal region. This domain and its N-terminal location are conserved among a family of fungal proteins of currently unknown function. Many proteins in this family are in the same size-range as Clr5, some also share with Clr5 a predicted unstructured domain in their C-terminal portion. In others we identified 1 to >10 ankyrin repeats (AR) in the place of the predicted unstructured region. AR form flexible bundles of stacked helix-loop-helix units connected by β-hairpins that create an interaction interface with other proteins [47]–[51]. AR proteins and IUPs resemble each other in their interactive plasticity and some AR proteins contain partly unstructured ankyrin repeats that become structured upon binding to a target surface, as exemplified by the NκBα repressor (reviewed in [48]). These shared properties of ARs and IUPs, and the fact that some members of the Clr5 protein family contain ARs while others contain unstructured regions, suggest that the predicted unstructured domain of Clr5 also mediates protein interactions. The predicted high flexibility of the unstructured domain is consistent with its relatively low sequence conservation between the Clr5 homologues in S. pombe, S. japonicus, and S. octosporus. Clr5 is the first member of its family with an assigned function. Its involvement in a well characterized biological process amenable to genetic analysis provides valuable tools to unravel questions relevant not only to the regulation of gene expression but also to the fields of structural biology and molecular evolution.

Methods

S. pombe strains and media

The strains used in this study and their genotypes are listed in Table S1. Some were published previously as indicated [15], [16], [18], [26], [52], [53], [54]. The clr5 ORF was replaced with the hph1 gene, which confers resistance to hygromycin B, by transforming SPK29 with a PCR product amplified from pCR2.1-hph1 [55] with GTO-312 (TTACATGTTTCCGGGGGTGTACCTTGGATCGCTCTATTTTATCATTTAACGTTGTTGTCATTCGTGCACTAAATTGATACACTATTTTCACCCCTACTTTACGAGCCACCACTACCACCAACTCTGGCCACTTCCAATCTCAACTTGAAACAACATTAGACAACCGAAAGTTCGATTTCACGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA) and GTO-313 (TAGGCAGGTAGGGCGAATGGTGAAGAAAAAAATTAAAAAACATCTAAATGATAATAAAGCAGAAACCAAAAGGGAATGCCAGAAAGGACCAACTAAAGATACAGGTACTAGTATAAATAGAGCAACACCATGGAAATGGTCAAAACCGCAAAGTGCAACAAGCGGCAATACTAACCTAAAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC) producing strain SPK458.

Targeted integration of ade6+ and mat locus elements into the ura4+ locus were essentially as described before [26]. The REIII containing sequence in AP1665, AP2346 and AP2406 is the 482 bp fragment described in [16]. Media were prepared as described previously [24], [56], [57].

Mutagenesis

The S. cerevisiae LEU2-containing plasmid pJJ283 [58] was digested to completion with BamHI and HindIII (New England Biolabs). 18 bp random ends were added to the LEU2 fragment by PCR using primers N-OKR 76 ((N)18-CTCAGGTATCGTAAGATGCAAGAGT) and N-OKR77 ((N)18 - CTCCATCAAATGGTCAGGTCATTG) (Figure S6). Insertional mutagenesis was essentially performed as a standard fission yeast transformation [56], [59], by transforming SPK29 with the LEU2 PCR products with random ends. Following the transformation, cells were plated onto AA-leu plates and incubated 3–5 days at 33°C before being replicated onto MSA supplemented with adenine and uracil to induce meiosis in the Leu+ transformants.

Inverse PCR

Inverse PCR was performed essentially as described previously [59] using the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche) and primers OKR78 (CTGTGCGATAGCGCCCCTGTGTGTTC) and OKR79 (ACTACGATTCCTAATTTGATATTGGAGG) in the cases where the genomic DNA had been digested with HindIII; OKR83 (GGAGAAAAACTGTGGAGGAAACCATCAAG) and OKR78, or OKR84 (GGGATAACGGAGGCTTCATCGGAG) and OKR79 for the EcoRI digests; and OKR82 (GGCATCAACCTTCTTGGAGGCTTCC) and OKR79 for the HinP1I digests (Figure S6).

RNA extraction and transcript analysis

Total RNA was extracted as described previously [60], [61]. For the clr5 transcript analysis, the clr5 mRNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript II (Qiagen) in a reaction containing OKR86 (GAGTGCGCATTGTGTGCATCAGCC) to prime cDNA synthesis and 25 µg of total RNA produced from PG1789. Diluted cDNA was amplified with Expand High Fidelity Polymerase (Roche) using OKR86 and JPO998 (CATCGAGCTTTCCAAGATCAATGGAATG). For the analysis of other transcripts, cultures of wild-type or mutant strains growing exponentially in YES medium were harvested and starved for nitrogen in PM medium for 5 hours at 32°C in a shaking incubator to induce sexual differentiation. RT-PCR was performed as described in [17], using OKR93 (CCCTGCTTATATGTAGTTTATAATTGTTGTGTCC) and OKR94 (CTATCAGGAGATTGGGCAGGTGCTTCAGCC) and 24 PCR cycles to amplify the mat2-Pc transcript; GTO-353 (CTCTTCATTCAATTGAAACTGGCAAAGGTG) and GTO-355 (CGTTTCTCCACATCTCTCCAACCAGCTTGG) and 24 PCR cycles to amplify the mat3-Mc transcript; GTO-265 (GCTATTCAGCTAGAGCTGAGGG) and GTO-266 (CTTCGACAACAGGATTACGACC) and 25 PCR cycles to amplify ura4+ and ura4-DS/E transcripts; GTO-223 (GAAAACACATCGTTGTCTTCAGAG) and GTO-226 (TCGTCTTGTAGCTGCATGTGA) and 27 PCR cycles to amplify RNA originating from centromeric repeats or cenH; or OKR70 (GGCATCACACTTTCTACAACG) and OKR71 (GAGTCCAAGACGATACCAGTG) and 23 PCR cycles for actin. No-RT controls were conducted with GTO-223 and GTO-226 and 27 PCR cycles for all RNA preparations used in RT-PCR. No products were observed in these reactions.

Real-time RT-PCR displayed in Figure 1 was performed as described [61] to detect mat2-Pc using JPO-976 (TTGAATATAGTATGCGCTCTAACTTGG) and JPO-977 (TGTTAGACTTGCCTGGTCACAATT). Real-time PCR displayed in Figure 8 was performed using a Qiagen Quantitect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit for the reactions and a BioRad CFX96 PCR machine and BioRad software for the analysis. Dilution series of RNA prepared from a h90 strain were used to determine the range of exponential amplification which was found to extend to at least 30 cycles. All reactions were set up in triplicate except for the no-RT controls for which only one reaction was set up per sample. The mat2-Pc transcript was amplified with JPO-976 and JPO-977 using 75 ng of total RNA as template for each sample. The actin transcript was amplified with q-act-FOR (GGTTTCGCTGGAGATGATG) and q-act-REV (ATACCACGCTTGCTTTGAG) using 75 pg RNA as template. No mat2-Pc transcript was detected under these conditions for the wild-type (PG1789); clr4Δ (SPK450); clr3Δ (PG3564); clr6-1 (SP1240); clr5Δ (PG3631); clr5-142 (SPK368) and clr6-1 clr5-142 (SPK493) RNA preparations. Values reported in Figure 8 for the relative increase in mat2-Pc transcript for the clr3Δ clr6-1 (PG3577); clr4Δ clr5Δ (PG3630) and clr3Δ clr5Δ (PG3633) RNA preparations are therefore likely to underestimate the real values.

Micro-array analysis

A clr5+ (SPK10) and a clr5Δ (SPK573) strain were propagated in liquid EMM2 medium, and harvested at a cell density of ∼5.0×106 cell/ml. RNA extraction and micro-array analysis were performed as described previously [62] in duplicate. The GeneSpring software package was used for data analysis and comparisons with previously published microarray experiments. The significance of gene list overlaps was calculated using a standard Fisher's exact test, and the P-values were adjusted with a Bonferroni multiple testing correction. Two lists of genes upregulated in the clr5Δ mutant were generated, one by selecting genes upregulated >2 fold in both microarray experiments and the other by selecting genes whose averaged expression was >2 fold (Table S2). Use of either list produced essentially the same results.

Plots examining the chromosomal distribution of genes upregulated >2 fold in the clr5Δ mutant were generated in R and show -log10 of the corrected P values of a Fisher's exact test between the lists of upregulated genes and genes in a sliding window of 20 genes along all three chromosomes (step = 1 gene, multiple testing correction is Bonferroni). Complete plots are shown in Figure S7 and an excerpt of chromosome 1 is shown in Figure 5E.

Cloning and sequencing of clr5 cDNA and clr5 mutant alleles

cDNA from exponentially growing wild-type cells (PG1789) was amplified using OKR86 and JPO998 as described above. A PCR product of approximately 600 bp was gel purified (Qiagen) and cloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen). The cloned cDNA was sequenced to identify the exon boundaries of clr5. To identify possible mutations within clr5 in the esp mutants [16], full-length genomic clr5 was amplified using primers OKR-95 (ATTCCCGGGGATGACGAAGGAATGGGAATGTCG) and OKR-96 (CTGCAGGTCGACCTAAACGAAACGAGAATCTACATCTGG), 18 PCR cycles and the Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes). PCR products from duplicate DNA samples from wild-type, esp1-, esp2-, esp3- and esp4- cells were TOPO-cloned and sequenced.

DAPI staining and microscopy

Cells propagated on ME plates for 3–4 days at 32°C were scraped, washed in 500 µl PBS, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min in 8 µg/ml DAPI/PBS solution. The suspension was diluted approximately 20 fold in PBS and 150 µl were spun (Cyto-Tek, Samura) onto poly-lysine coated slides (Sigma). The slides were air-dried and one drop of Vectashield (Vector Labs) was added before applying the cover slip. Images were obtained using a Zeiss AxioskopII microscope fitted with Lud1 filter wheel and chroma filters, and a Coolsnap HQ camera. All images were taken at maximum resolution, using 100x objective and IPLab software (Scanlytics).

Localization of Clr5

Clr5 tagged at its C terminus with GFP [52] was expressed from the endogenous clr5 locus and used for localization studies. Cells were propagated to early log phase in supplemented EMM2 medium. Images were obtained using the 100x objective of a Zeiss Axio Imager fluorescence microscope equiped with a Hamamatsu Orca-ER digital camera and Volocity 5.0.

DNA and protein sequence analyses

Sequence analyses were performed using online available BLAST [63], ClustalW (www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/), IUPred (http://iupred.enzim.hu/), and services from the Sanger Institute (www.sanger.ac.uk) and Broad Institute (www.broad.mit.edu)

ChIP analyses

Cells were grown overnight in YES in a 30°C shaking incubator, diluted to 3.5×106 cells/ml in malt extract medium (ME) and incubated for a further 5 hr to induce nitrogen starvation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described [61], but using 1% fixation and antibodies that recognize H3K9me2 (Abcam) or H3K9Ac (Millipore). Briefly, 3×108 cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 18 min at room temperature prior to washing with PBS, permeabilization of the cell wall with zymolyase 100T (0.4 mg/ml in PEMS), and incubation at 36°C for 20 min. Following extensive washing with PEMS, cell pellets were resuspended in 400 µl ChIP lysis buffer and sonicated (3x, 10s each). After pre-clearing with Protein A - agarose beads, the lysates were used for immunoprecipitation overnight with each antibody. Antibody-protein complexes were purified using Protein A - agarose beads, washed, and reverse-crosslinking of samples was performed by overnight incubation at 65°C in TES, followed by Proteinase K digestion. DNA was purified using the Wizard DNA cleanup kit (Promega) and used for Real-time PCR. Real-time PCR was performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler ep Realplex machine using Quantifast Sybr green (Qiagen). Data was analyzed using the ΔCt method, ensuring that all samples gave Ct values within the experimentally determined linear range. Primers for RE II were JPO-1102 (AACATGTTCCTTCGCCTACG) and JPO-1104 (CCGTTGTTGTATGGGTCCTT). Primers for adh1 were JPO-793 (AACGTCAAGTTCGAGGAAGTCC) and JPO-794 (AGAGCGTGTAAATCGGTGTGG). Primers for mat2-Pc were JPO-976 and JPO-977. Data were normalized to the clr4Δ strain for the K9Me ChIPs, and to wild type for the K9Ac ChIPs.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KlarAJ

2007 Lessons learned from studies of fission yeast mating-type switching and silencing. Annu Rev Genet 41 213 236

2. KellyM

BurkeJ

SmithM

KlarA

BeachD

1988 Four mating-type genes control sexual differentiation in the fission yeast. EMBO J 7 1537 1547

3. GrewalSIS

BonaduceMJ

KlarAJS

1998 Histone deacetylase homologs regulate epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional silencing and chromosome segregation in fission yeast. Genetics 150 563 576

4. BjerlingP

SilversteinRA

ThonG

CaudyA

GrewalS

2002 Functional divergence between histone deacetylases in fission yeast by distinct cellular localization and in vivo specificity. Mol Cell Biol 22 2170 2181

5. BannisterAJ

ZegermanP

PartridgeJF

MiskaEA

ThomasJO

2001 Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410 120 124

6. ZhangK

MoschK

FischleW

GrewalSI

2008 Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15 381 388

7. SadaieM

IidaT

UranoT

NakayamaJ

2004 A chromodomain protein, Chp1, is required for the establishment of heterochromatin in fission yeast. EMBO J 23 3825 3835

8. GrewalSIS

KlarAJ

1997 A recombinationally repressed region between mat2 and mat3 loci shares homology to centromeric repeats and regulates directionality of mating-type switching in fission yeast. Genetics 146 1221 1238

9. VolpeTA

KidnerC

HallIM

TengG

GrewalSI

2002 Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297 1833 1837

10. CamHP

SugiyamaT

ChenES

ChenX

FitzGeraldPC

2005 Comprehensive analysis of heterochromatin - and RNAi-mediated epigenetic control of the fission yeast genome. Nat Genet 37 809 819

11. HallIM

ShankaranarayanaGD

NomaK

AyoubN

CohenA

2002 Establishment of a heterochromatin domain. Science 297 2232 2236

12. JiaS

NomaK

GrewalSIS

2004 RNAi-independent heterochromatin nucleation by the stress-activated ATF1/CREB family proteins. Science 304 1971 1976

13. KimHS

ChoiES

ShinJA

JangYK

ParkSD

2004 Regulation of Swi6/HP1-dependent heterochromatin assembly by cooperation of components of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and a histone deacetylase Clr6. J Biol Chem 279 42850 42859

14. YamadaT

FischleW

SugiyamaT

AllisD

GrewalSIS

2005 The nucleation and maintenance of heterochromatin by a histone deacetylase in fission yeast. Mol Cell 20 173 185

15. ThonG

CohenA

KlarAJ

1994 Three additional linkage groups that repress transcription and meiotic recombination in the mating-type region of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 138 29 38

16. ThonG

BjerlingKP

NielsenIS

1999 Localization and properties of a silencing element near the mat3-M mating-type cassette of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 151 945 963

17. ThonG

HansenKR

AltesSP

SidhuD

SinghG

2005 The Clr7 and Clr8 directionality factors and the Pcu4 cullin mediate heterochromatin formation in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 171 1583 1595

18. HansenKR

BurnsG

MataJ

VolpeTA

MartienssenRA

2005 Global effects on gene expression in fission yeast by silencing and RNA interference machineries. Mol Cell Biol 25 590 601

19. MataJ

LyneR

BurnsG

BählerJ

2002 The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat Genet 32 143 147

20. IshiiK

OgiyamaY

ChikashigeY

SoejimaS

MasudaF

2008 Heterochromatin integrity affects chromosome reorganization after centromere dysfunction. Science 321 1088 1091

21. AllshireRC

NimmoER

EkwallK

JaverzatJ

CranstonG

1995 Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev 9 218 233

22. ThonG

Verhein-HansenJ

2000 Four chromo-domain proteins of Schizosaccharomyces pombe differentially repress transcription at various chromosomal locations. Genetics 155 551 568

23. GrewalSIS

KlarAJ

1996 Chromosomal inheritance of epigenetic states in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell 86 95 101

24. ThonG

FriisT

1997 Epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional silencing and switching competence in fission yeast. Genetics 145 685 696

25. AyoubN

NomaK

IsaacS

KahanT

GrewalSI

2003 A novel jmjC domain protein modulates heterochromatization in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 23 4356 4370

26. AyoubN

GoldschmidtI

LyakhovetskyR

CohenA

2000 A fission yeast repression element cooperates with centromere-like sequences and defines a mat silent domain boundary. Genetics 156 983 994

27. SugiyamaT

CamH

VerdelA

MoazedD

GrewalSI

2005 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is an essential component of a self-enforcing loop coupling heterochromatin assembly to siRNA production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 152 157

28. MotamediMR

HongEJ

LiX

GerberS

DenisonC

2008 HP1 proteins form distinct complexes and mediate heterochromatic gene silencing by nonoverlapping mechanisms. Mol Cell 32 778 790

29. SadaieM

KawaguchiR

OhtaniY

ArisakaF

TanakaK

2008 Balance between distinct HP1 family proteins controls heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 28 6973 6988

30. FischerT

CuiB

DhakshnamoorthyJ

ZhouM

RubinC

2009 Diverse roles of HP1 proteins in heterochromatin assembly and functions in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 8998 9003

31. WirénM

SilversteinRA

SinhaI

WalfridssonJ

LeeHM

2005 Genomewide analysis of nucleosome density histone acetylation and HDAC function in fission yeast. EMBO J 24 2906 18

32. SinhaI

WirénM

EkwallK

2006 Genome-wide patterns of histone modifications in fission yeast. Chromosome Res 14 95 105

33. EkwallK

2005 Genome-wide analysis of HDAC function. Trends Genet 21 608 615

34. ChenES

ZhangK

NicolasE

CamHP

ZofallM

2008 Cell cycle control of centromeric repeat transcription and heterochromatin assembly. Nature 451 734 737

35. CzerminB

SchottaG

HülsmannBB

BrehmA

BeckerPB

2001 Physical and functional association of SU(VAR)3-9 and HDAC1 in Drosophila. EMBO Rep 2 915 919

36. ZhangCL

McKinseyTA

OlsonEN

2002 Association of class II histone deacetylases with heterochromatin protein 1: potential role for histone methylation in control of muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 22 7302 7312

37. AparicioOM

GottschlingDE

1994 Overcoming telomeric silencing: a trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev 8 1133 1146

38. XuEY

ZawadzkiKA

BroachJR

2006 Single-cell observations reveal intermediate transcriptional silencing states. Mol Cell 23 219 229

39. MartienssenRA

ZaratieguiM

GotoDB

2005 RNA interference and heterochromatin in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Trends Genet 8 450 456

40. KanohJ

WatanabeY

OhsugiM

LinoY

YamamotoM

1996 Schizosaccharomyces pombe gad7+ encodes a phosphoprotein with a bZIP domain, which is required for proper G1 arrest and gene expression under nitrogen starvation. Genes Cells 1 391 408

41. KonN

KrawchukMD

WarrenBG

SmithGR

WahlsWP

1997 Transcription factor Mts1/Mts2 (Atf1/Pcr1, Gad7/Pcr1) activates the M26 meiotic recombination hotspot in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 13765 13770

42. LeemY

RipmasterTL

KellyFD

EbinaH

HeincelmanME

2008 Retrotransposon Tf1 is targeted to pol II promoters by transcription activators. Mol Cell 30 98 107

43. DeshpandeGP

HaylesJ

HoeKL

KimDU

ParkHO

2009 Screening a genome-wide S. pombe deletion library identifies novel genes and pathways involved in genome stability maintenance. DNA Repair (Amst) 8 672 679

44. NicolasE

YamadaT

CamHP

FitzgeraldPC

KobayashiR

2007 Distinct roles of HDAC complexes in promoter silencing, antisense suppression and DNA damage protection. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 372 380

45. WrightPE

DysonHJ

2009 Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol 19 31 38

46. MészárosB

TompaP

SimonI

DosztányiZ

2007 Molecular principles of the interactions of disordered proteins. J Mol Biol 372 549 561

47. BorkP

1993 Hundreds of ankyrin-like repeats in functionally diverse proteins: mobile modules that cross phyla horizontally? Proteins 17 363 374

48. BarrickD

FerreiroDU

KomivesEA

2008 Folding landscapes of ankyrin repeat proteins: experiments meet theory. Curr Opin Struct Biol 18 27 34

49. ZhangA

YeungPL

LiCW

TsaiSC

DinhGK

2004 Identification of a novel family of ankyrin repeats containing cofactors for p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. J Biol Chem 279 33799 33805

50. SedgwickSG

SmerdonSJ

1999 The ankyrin repeat: a diversity of interactions on a common structural framework. Trends Biochem Sci 24 311 316

51. LiJ

MahajanA

TsaiMD

2006 Ankyrin repeat: a unique motif mediating protein-protein interactions. Biochemistry 45 15168 15178

52. HayashiA

DingDQ

TsutsumiC

ChikashigeY

MasudaH

2009 Localization of gene products using a chromosomally tagged GFP-fusion library in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells 14 217 225

53. ThonG

KlarAJ

1992 The clr1 locus regulates the expression of the cryptic mating-type loci of fission yeast. Genetics 131 287 296

54. NielsenIS

NielsenO

MurrayJM

ThonG

2002 The fission yeast ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UbcP3, Ubc15, and Rhp6 affect transcriptional silencing of the mating-type region. Eukaryot Cell 1 613 625

55. SatoM

DhutS

TodaT

2005 New drug-resistant cassettes for gene disruption and epitope tagging in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 7 583 591

56. MorenoS

KlarAJS

NurseP

1991 Molecular genetic analysis of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Method Enzymol 194 795 823

57. PetrieVJ

WuitschickJD

GivensCD

KosinskiAM

PartridgeJF

2005 RNA interference (RNAi)-dependent and RNAi-independent association of the Chp1 chromodomain protein with distinct heterochromatic loci in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 25 2331 2346

58. JonesJ

PrakashL

1990 Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae selectable markers in pUC18 polylinkers. Yeast 6 363 366

59. ChuaG

TaricaniL

StrangleW

YoungPG

2000 Insertional mutagenesis based on illegitimate recombination in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res 28 e53

60. HansenKR

IbarraPT

ThonG

2006 Evolutionary-conserved telomere-linked helicase genes of fission yeast are repressed by silencing factors, RNAi components and the telomere-binding protein Taz1. Nucleic Acids Res 34 78 88

61. PartridgeJF

DeBeauchampJL

KosinskiAM

UlrichDL

HadlerMJ

2007 Functional separation of the requirements for establishment and maintenance of centromeric heterochromatin. Mol Cell 26 593 602

62. LyneR

BurnsG

MataJ

PenkettCJ

RusticiG

2003 Whole-genome microarrays of fission yeast: characteristics, accuracy, reproducibility, and processing of array data. BMC Genomics 4 27

63. AltschulSF

GishW

MillerW

MyersEW

LipmanDJ

1990 Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215 403 410

64. De CastroE

SigristCJ

GattikerA

BulliardV

Langendijk-GenevauxPS

2006 ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 34 Web Server issue W362 365

65. MataJ

BählerJ

2006 Global roles of Ste11p, cell type, and pheromone in the control of gene expression during early sexual differentiation in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 15517 15522

66. KupferDM

DrabenstotSD

BuchananKL

LaiH

ZhuH

2004 Introns and splicing elements of five diverse fungi. Eukaryot Cell 3 1088 1100

67. CaspariT

1997 Onset of gluconate-H+ symport in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is regulated by the kinase Wis1 and Pka1, and requires the gti+ gene product. J Cell Science 110 2599 2608

68. HarigayaY

YamamotoM

2007 Molecular mechanisms underlying the mitosis-meiosis decision. Chromosome Res 15 523 537

69. HeilandS

RadonovicN

HoferM

WinderrickxJ

LichtenbergH

2000 Multiple Hexose transporters of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Bacteriol 182 2153 2162

70. MataJ

BählerJ

2006 Global roles of Ste11p, cell type, and pheromone in the control of gene expression during early sexual meiosis differentiation in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 15517 15522

71. Xue-FranzénY

KjærulffS

HolmbergC

WrightA

NielsenO

2006 Genomewide identification of pheromone-targeted transcription in fission yeast. BMC Genomics 7 1 18

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Composite Effects of Polymorphisms near Multiple Regulatory Elements Create a Major-Effect QTLČlánek Horizontal Transfer, Not Duplication, Drives the Expansion of Protein Families in ProkaryotesČlánek Segregating Variation in the Polycomb Group Gene Alters the Effect of Temperature on Multiple TraitsČlánek Global Analysis of the Impact of Environmental Perturbation on -Regulation of Gene ExpressionČlánek A Mutation in the Gene Encoding Mitochondrial Mg Channel MRS2 Results in Demyelination in the Rat

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Scans Identifies IL18RAP, PTPN2, TAGAP, and PUS10 As Shared Risk Loci for Crohn's Disease and Celiac Disease

- Composite Effects of Polymorphisms near Multiple Regulatory Elements Create a Major-Effect QTL

- Horizontal Transfer, Not Duplication, Drives the Expansion of Protein Families in Prokaryotes

- Genome-Wide Association Study SNPs in the Human Genome Diversity Project Populations: Does Selection Affect Unlinked SNPs with Shared Trait Associations?

- Friedreich's Ataxia (GAA)•(TTC) Repeats Strongly Stimulate Mitotic Crossovers in

- Zebrafish Mutation Leads to mRNA Splicing Defect and Pituitary Lineage Expansion

- Histone H4 Lysine 12 Acetylation Regulates Telomeric Heterochromatin Plasticity in

- Bub1-Mediated Adaptation of the Spindle Checkpoint

- Segregating Variation in the Polycomb Group Gene Alters the Effect of Temperature on Multiple Traits

- Signaling Role of Fructose Mediated by FINS1/FBP in

- RNF12 Activates and Is Essential for X Chromosome Inactivation

- Comparative Study between Transcriptionally- and Translationally-Acting Adenine Riboswitches Reveals Key Differences in Riboswitch Regulatory Mechanisms

- Global Analysis of the Impact of Environmental Perturbation on -Regulation of Gene Expression

- Application of a New Method for GWAS in a Related Case/Control Sample with Known Pedigree Structure: Identification of New Loci for Nephrolithiasis

- H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

- A Mutation in the Gene Encoding Mitochondrial Mg Channel MRS2 Results in Demyelination in the Rat

- Transcription Initiation Patterns Indicate Divergent Strategies for Gene Regulation at the Chromatin Level

- The Transposon-Like Correia Elements Encode Numerous Strong Promoters and Provide a Potential New Mechanism for Phase Variation in the Meningococcus

- Proteins Encoded in Genomic Regions Associated with Immune-Mediated Disease Physically Interact and Suggest Underlying Biology

- A Novel RNA-Recognition-Motif Protein Is Required for Premeiotic G/S-Phase Transition in Rice ( L.)

- The Mucin-Like Protein OSM-8 Negatively Regulates Osmosensitive Physiology Via the Transmembrane Protein PTR-23

- Genome Sequencing and Comparative Transcriptomics of the Model Entomopathogenic Fungi and

- Rnf12—A Jack of All Trades in X Inactivation?

- Joint Genetic Analysis of Gene Expression Data with Inferred Cellular Phenotypes

- Evolutionary Conserved Regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB

- Quaking Regulates Expression through Its 3′ UTR in Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- H3K9me-Independent Gene Silencing in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin by Clr5 and Histone Deacetylases

- Evolutionary Conserved Regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB

- Rnf12—A Jack of All Trades in X Inactivation?

- Joint Genetic Analysis of Gene Expression Data with Inferred Cellular Phenotypes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání