-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaDirect Recognition of by the NK Cell Natural Cytotoxicity Receptor NKp46 Aggravates Periodontal Disease

Periodontitis is a common human chronic inflammatory disease that results in the destruction of the tooth attachment apparatus and tooth loss. Although infections with periopathogenic bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) and Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) are essential for inducing periodontitis, the nature and magnitude of the disease is determined by the host's immune response. Here, we investigate the role played by the NK killer receptor NKp46 (NCR1 in mice), in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Using an oral infection periodontitis model we demonstrate that following F. nucleatum infection no alveolar bone loss is observed in mice deficient for NCR1 expression, whereas around 20% bone loss is observed in wild type mice and in mice infected with P. gingivalis. By using subcutaneous chambers inoculated with F. nucleatum we demonstrate that immune cells, including NK cells, rapidly accumulate in the chambers and that this leads to a fast and transient, NCR1-dependant TNF-α secretion. We further show that both the mouse NCR1 and the human NKp46 bind directly to F. nucleatum and we demonstrate that this binding is sensitive to heat, to proteinase K and to pronase treatments. Finally, we show in vitro that the interaction of NK cells with F. nucleatum leads to an NCR1-dependent secretion of TNF-α. Thus, the present study provides the first evidence that NCR1 and NKp46 directly recognize a periodontal pathogen and that this interaction influences the outcome of F. nucleatum-mediated periodontitis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 8(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002601

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002601Summary

Periodontitis is a common human chronic inflammatory disease that results in the destruction of the tooth attachment apparatus and tooth loss. Although infections with periopathogenic bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) and Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) are essential for inducing periodontitis, the nature and magnitude of the disease is determined by the host's immune response. Here, we investigate the role played by the NK killer receptor NKp46 (NCR1 in mice), in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Using an oral infection periodontitis model we demonstrate that following F. nucleatum infection no alveolar bone loss is observed in mice deficient for NCR1 expression, whereas around 20% bone loss is observed in wild type mice and in mice infected with P. gingivalis. By using subcutaneous chambers inoculated with F. nucleatum we demonstrate that immune cells, including NK cells, rapidly accumulate in the chambers and that this leads to a fast and transient, NCR1-dependant TNF-α secretion. We further show that both the mouse NCR1 and the human NKp46 bind directly to F. nucleatum and we demonstrate that this binding is sensitive to heat, to proteinase K and to pronase treatments. Finally, we show in vitro that the interaction of NK cells with F. nucleatum leads to an NCR1-dependent secretion of TNF-α. Thus, the present study provides the first evidence that NCR1 and NKp46 directly recognize a periodontal pathogen and that this interaction influences the outcome of F. nucleatum-mediated periodontitis.

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory periodontal disease is initiated by several bacterial pathogens. The infection leads to an inflammatory process which results in the destruction of the dental attachment apparatus associated with tooth loss in adults over the age of 35. As such, it affects about one-half of working American adults [1].

The health risks of periodontal disease are not limited to the dentition. Increasing evidence suggests that periodontitis may be an aggravating factor which significantly enhances the risk for developing bacterial endocarditis, aspiration pneumonia, osteomyelitis in children, preterm low birth weight, coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus [2]–[7]. Recently, several reports also showed a strong association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis [8]. This correlation may have a causative nature due to protein citrullination by P. gingivalis [9]. Nevertheless, although the presence of a periodontal pathogen is prerequisite for periodontitis development, the progression of the disease is dependent on the host innate and adaptive immune responses [10].

NK cells, which are part of the innate immunity, are able to directly kill tumor and virus-infected cells and are also a source for immune mediating cytokines [11]. The function of NK cells is controlled by both inhibitory and activating receptors [12], [13]. When the activity of NK cells is balanced towards activation, it leads to enhanced killing, enhanced production of cytokines, or both [14], [15]. The activating NK receptors includes: the NKp44, NKp30 and NKp46 receptors collectively known as NCR (Natural Cytotoxicity Receptors), 2B4, NKp80, CD16 and NKG2D. The ligands recognized by these receptors are either induced by stress (ligands for NKG2D, see [11], [16]), are viral proteins such as hemagglutinin (ligands for NKp44 and NKp46, see [17], [18]) and pp65 (ligands for NKp30, see [19]), are self-ligands [20] or are unknown tumor ligands. Among the NK activating receptors, the NKp46 receptor (NCR1 in mice) is the only receptor that is expressed specifically by NK cells of both human and mice [11], [21]. The direct in vivo role played by NKp46 in the killing of some tumors, influenza virus-infected cells and even self-beta cells was demonstrated using mice in which the NKp46 receptor is “knocked-out” (Ncr1gfp/gfp mice, see [20], [21]). Importantly, with regard to the current research, NKp46 is not only involved in NK cytotoxicity, but also in production of cytokines [15], [22].

The activity of NK cells in periodontitis has been scarcely studied and to the best of our knowledge, the involvement of the NK killer receptors in the disease was not investigated at all. This is quite surprising since impaired NK cells cytotoxicity has been described in several genetic and acquired conditions associated with periodontal involvement [23]–[26]. It has also been well documented that the local inflammatory response to periodontal bacteria is maintained and amplified by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL1-β [10], [27], [28], the former two being produced by NK cells [29], [30]. In addition, a role for antimicrobial peptides, which are also secreted by NK cells [31], [32], has been also implicated in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease [33], [34].

The present study aimed to address the role of NK cells in general, and of their activating receptor NKp46, in particular, in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. We demonstrate that F. nucleatum, a major etiologic bacteria involved in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease, is directly recognized by the mouse NCR1 and by the human NKp46 receptors and we show that the interaction between NCR1 and F. nucleatum probably leads to a rapid and specific secretion of TNF-α, resulting in alveolar bone loss. Collectively our results demonstrate that NK cells through their killing receptor NKp46 play a critical role in the pathogenesis of F. nucleatum-mediated periodontal disease.

Results

NCR1 controls the F. nucleatum-mediated alveolar bone loss

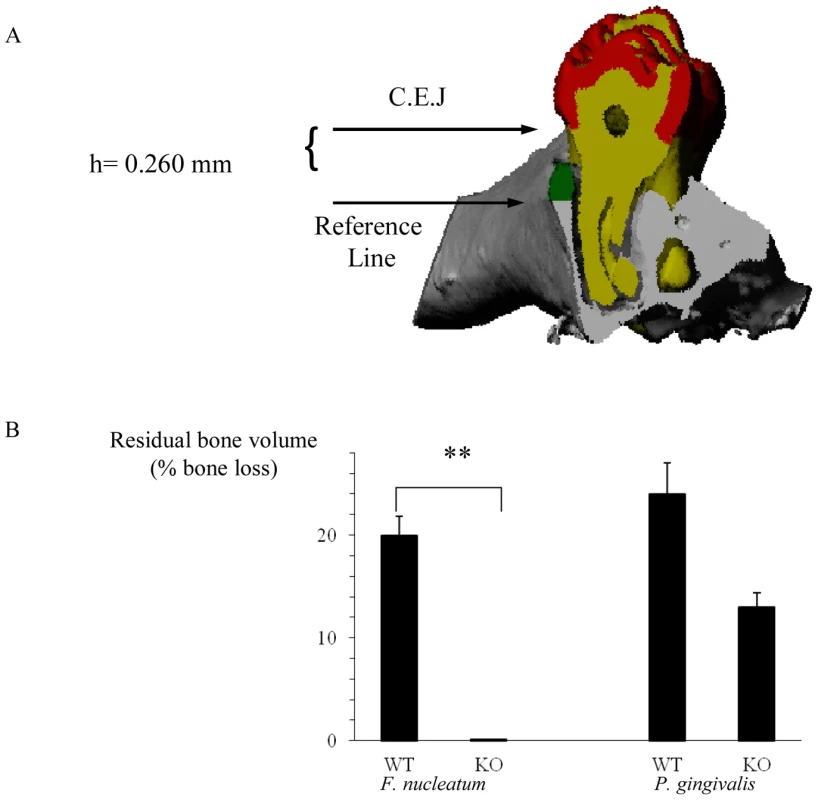

The important clinical outcome of oral inflammation that is induced by periodontal pathogens is the degradation of gingival connective tissue and the loss of alveolar bone which supports the teeth. Although the mechanisms underlying the inflammatory process which leads to the destruction of the supporting apparatus are not fully understood, TNF-α was demonstrated to be critical for disease induction [35]–[37]. Because TNF-α is secreted by NK cells and because NKp46 triggering can lead to TNF-α secretion we wondered whether NCR1 is involved in alveolar bone loss. To investigate this, we induced experimental periodontitis in wild type C57BL/6 mice and in the NCR1 knockout mice (Ncr1gfp/gfp, C57BL/6 background) that were generated in our laboratory by replacing the Ncr1 gene with GFP [21]. Mice were orally infected with F. nucleatum and with P. gingivalis and the levels of alveolar bone loss were quantified by micro-CT ([38], [39], Figure 1A). Around 20% bone loss was observed in the Ncr1+/+ wild type C57BL mice infected with F. nucleatum, compared to the Ncr1gfp/gfp KO mice in which bone loss was not detected at all (Figure 1B). Infection with P. gingivalis also resulted in alveolar bone loss which was similar to that of F. nucleatum. However, this bone loss was observed in both wild type and Ncr1gfp/gfp KO mice and no statistically significant differences were observed between the mice (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1. NCR1-dependent bone loss.

(A) Mesio-distal view on a random section. Red, yellow, gray and green represent the enamel, dentin, bone and the residual bone area above the reference line, respectively. (B) Ncr1+/+ (WT) and Ncr1gfp/gfp (KO) mice (n = 8 in each group) were challenged orally three times at 2-day intervals with inoculums of F. nucleatum and of P. gingivalis (2×108 CFU in 0.2 ml of PBS and 2% carboxymethylcellulose). Six weeks later, the jaws were harvested and the residual alveolar bone volume (mm3×10−3) was measured. Error bars represent SD. Data represent percentage of bone loss ± SD and are average of two independent experiments. ** p<0.01. The difference in bone loss between the KO and the WT mice following P. gingivalis inoculation was not statistically significant, p<0.09. Infiltration of immune cells into infected subcutaneous chambers

The experimental periodontis model is not suitable for investigating NK cell activities because of technical problems, tissue limitations and due to ethical restrictions. Therefore, to further investigate the role played by NK cells in F. nucleatum infection we used subcutaneous chambers which were implanted into mice in the dorsolumbar region [40], [41]. This model allows the direct quantification of inflammatory cells and mediators in the inflammatory exudates following bacterial challenge [40].

Subcutaneous chambers were implanted in Ncr1gfp/gfp KO mice. Two weeks after the implantation, when the outer incision healed completely and the chambers became encapsulated by a thin vascularized layer of fibrous connective tissue, the chambers were inoculated with the two periodontal pathogens F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, or with Escherichia coli (E. coli, used as a non–periodontal gram negative bacterial control).

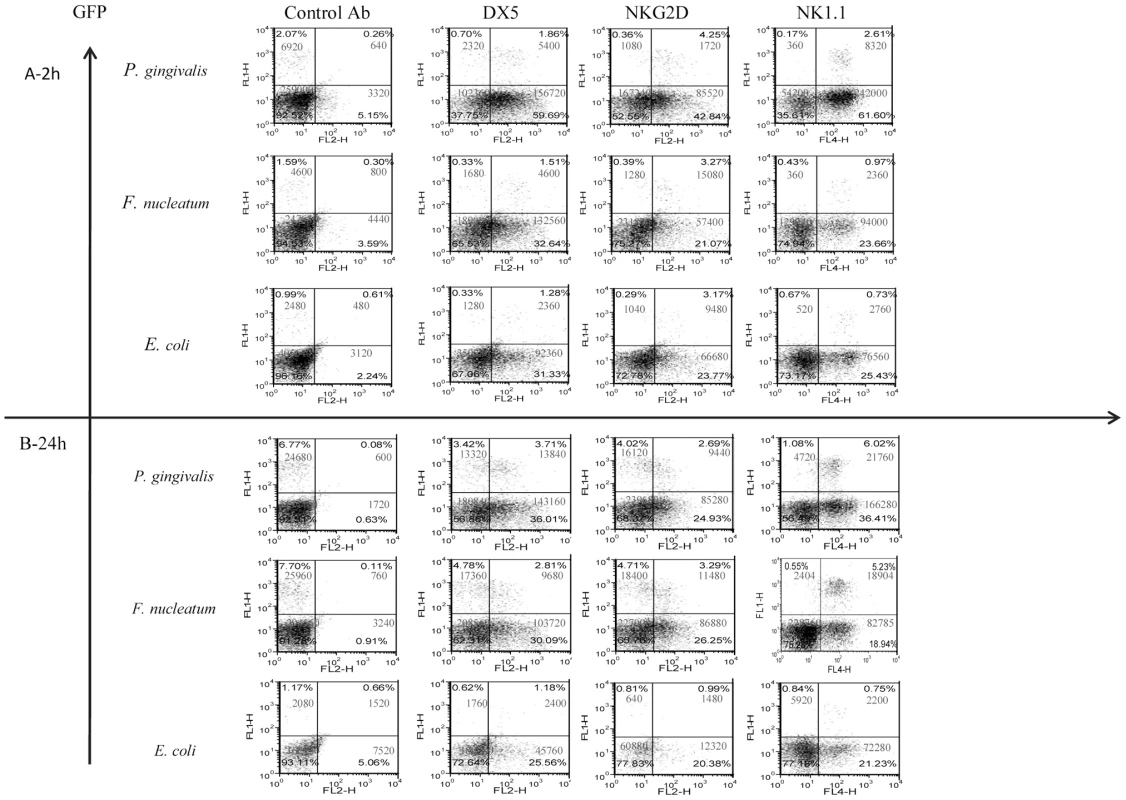

In agreement with previous reports [41], [42], a rapid and massive leukocyte infiltrate was observed in the chamber exudates following bacterial inoculation (Figure 2). NK cells (GFP-positive) were detected in the chambers as early as 2 hours post inoculation (Figure 2, left quadrates). The percentages and the numbers of NK cells increased at 24 hours following the inoculation, except for the E. coli-inoculated group (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Infiltration of cells into challenged chambers.

Immune cells in the chambers were analyzed by FACS 2 hours (A) and 24 hours (B) following bacteria inoculation. The intrinsic GFP labeling marks mainly NK cells. Staining was performed with Phycoerythrin conjugated anti-DX5 and anti-NKG2D mAbs. Staining with NK1.1 was visualized by using Cy-5 conjugated strepavidin. The cell percentage and cell numbers is indicated in each quadrant. One representative experiment out of four is shown. To further characterize the NK population that accumulated in the chambers following bacteria inoculation, we stained the cell content of the chambers with antibodies directed against NK cell receptors; NKG2D, DX5 and NK1.1. As can be seen in Figure 2, all of the GFP labeled NK cells were NK1.1 positive and CD3 negative (not shown) and most of them, at 2 hours post infection, were DX5 and NKG2D positive. A reduction in the expression of DX5 and of NKG2D on NK cells was observed twenty-four hours following the inoculation of F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis (Figure 2). Notably, NK cells (GFP positive) were the minor immune cell population present in the chambers (Figure 2) as most of cells that express NK cell markers such as NKG2D, DX5 and NK1.1, were actually GFP negative, (Figure 2).

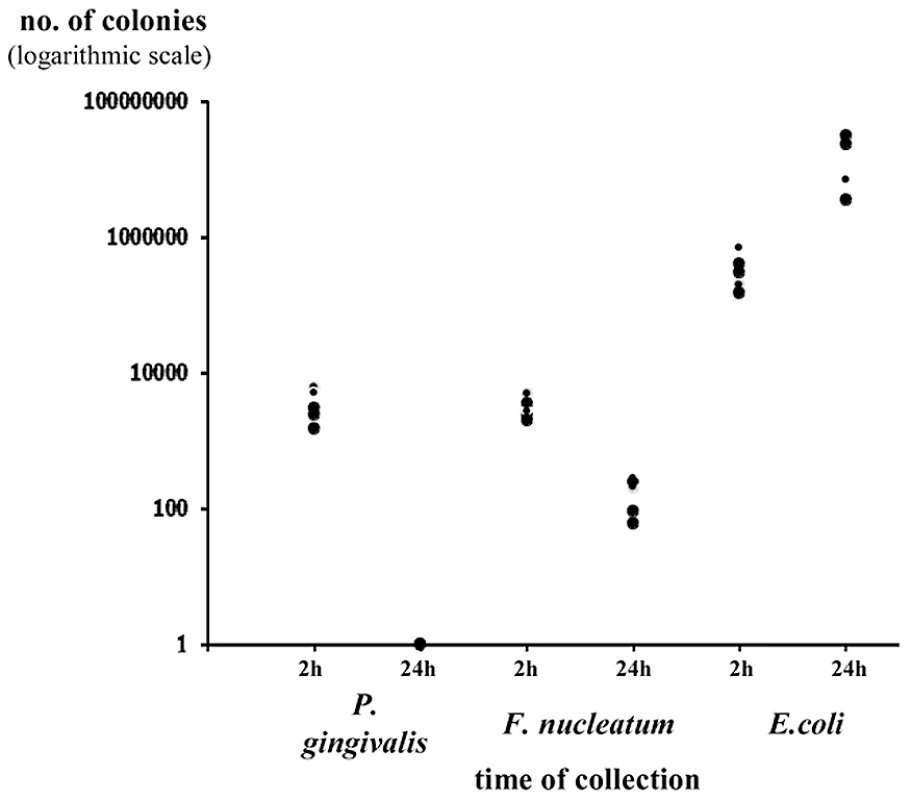

The presence or absence of NKp46 did not affect bacterial loads in the chambers (data not shown and figures below). Furthermore, both P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum bacteria were detected in the chambers 2 hours following inoculation and little or no bacteria was detected at 24 hours following inoculation (Figure 3 depicting the Ncr1gfp/gfp mice, and data not shown). In contrast, the E. coli load was significantly increased during the tested period (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Survival of bacteria in chamber exudates.

Viable CFU from chamber exudates were determined, 2 h and 24 h following inoculation of P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum or E. coli. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. One representative experiment out of four is shown. The y axis represents number of colonies (logarithmic scale). Thus, we conclude that the vast majority of lymphocytes in the chambers are not NK cells, that the in vivo accumulation of lymphocytes in the chambers is rapid, that low percentages and numbers of NK cells are observed in the chambers and that the NK cell percentages and numbers increase with time concomitantly with the disappearance of the two periodontal pathogens.

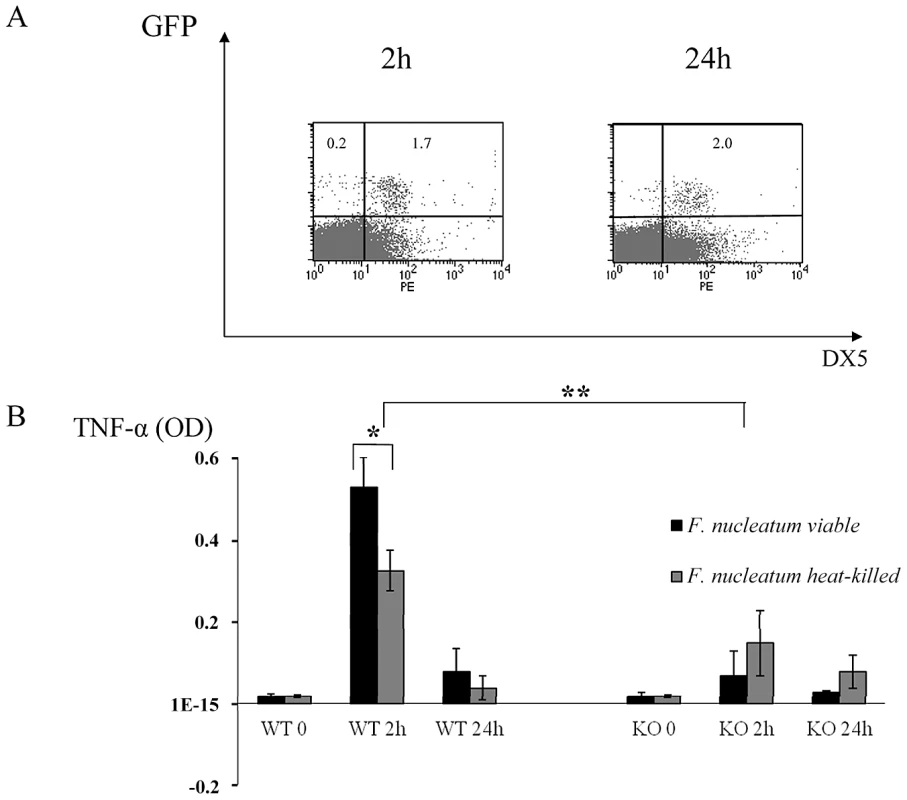

F. nucleatum inoculation leads to an NCR1-dependent accumulation of TNF-α

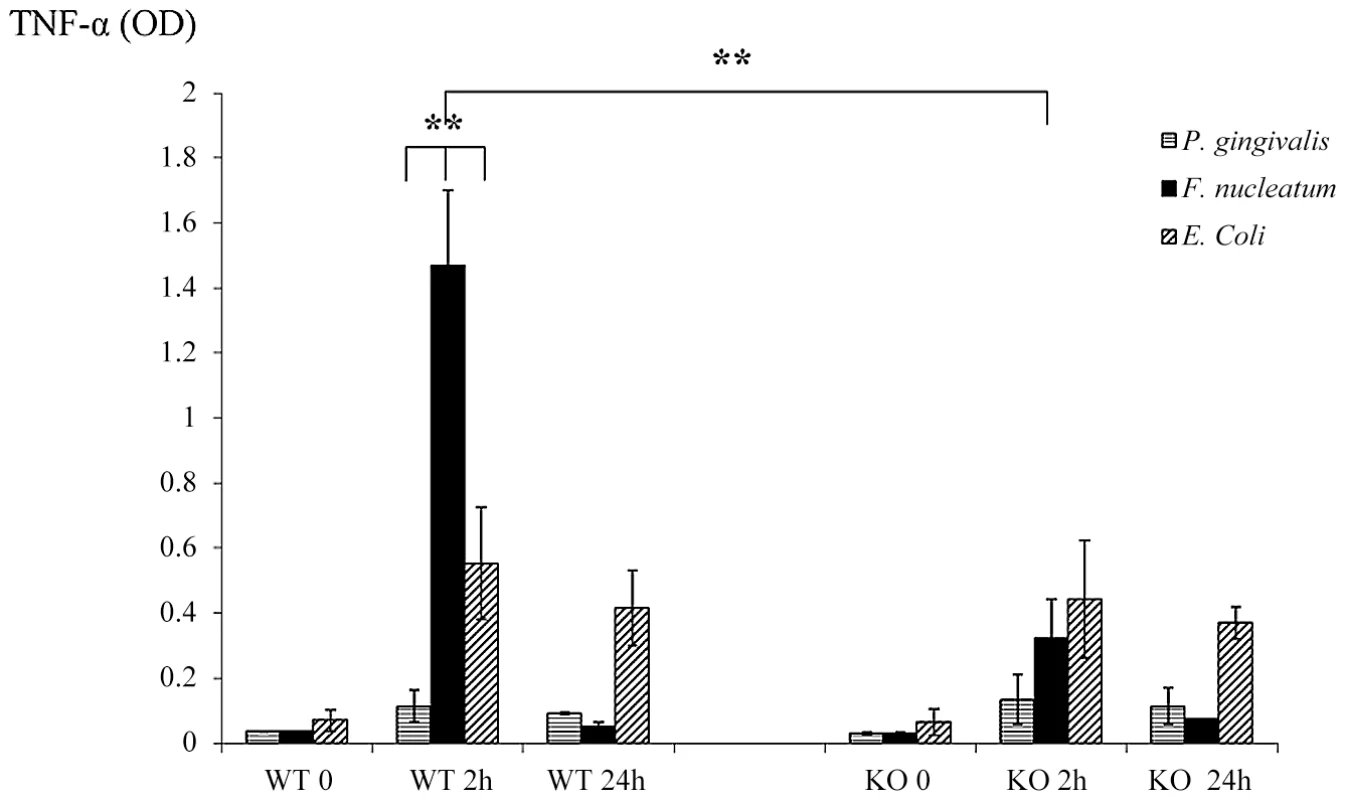

NKp46/NCR1 is an activating receptor involved in the killing of virus-infected, tumor cells and self-cells [20], [21] and in the secretion of IFN-γ and of TNF-α in response to various stimulations [29]. We therefore next examined whether the absence of NCR1 will affect the cytokines milieu that is present in the chambers exudates. The exudates of all chambers were collected at time 0 (before inoculation), at 2 and at 24 hours post inoculation and IFN-γ and TNF-α levels were measured. Under the tested experimental conditions, the levels of IFN-γ in the chambers could hardly be detected (data not shown). In contrast, a significant and rapid increase in the levels of TNF-α was observed in the Ncr1+/+ WT mice, 2 hours following the challenge with F. nucleatum (Figure 4). This elevation was NCR1 dependent, since the levels of TNF-α in the F. nucleatum-challenged Ncr1gfp/gfp KO mice were only modestly increased (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Cytokine profiles in challenged chambers.

TNF-α levels were determined by ELISA in chamber exudates of Ncr1+/+ (WT) and Ncr1gfp/gfp (KO) mice at baseline (0), 2 h and 24 h following bacterial challenge. Data represent absorbance at 650 nm ± SD and are average of three different experiments. ** p<0.01. In agreement with the above results, twenty four hours post inoculation of F. nucleatum, concomitantly with the disappearance of the bacteria (Figure 3), the TNF-α amounts in the exudates dropped to minimal in both the Ncr1+/+ WT and the Ncr1gfp/gfp KO mice (Figure 4).

Interestingly, P. gingivalis did not induce TNF-α secretion. Increase in TNF-α secretion was also observed following E. coli inoculation however this increase was NCR1 independent and was less pronounced as compared with F. nucleatum-mediated secretion (Figure 4). Furthermore, in agreement with the presence of E. coli in the chambers during the entire tested time period (Figure 3), the increased TNF-α secretion observed following E. coli inoculation did not significantly changed between 2 hours and 24 hours.

We also tried performing an intracellular staining for TNF-α in the NK cells isolated from the chambers. However, these NK cells did not survive the 5 hours Brefeldin A treatment, and without this treatment we could not detect TNF-α.

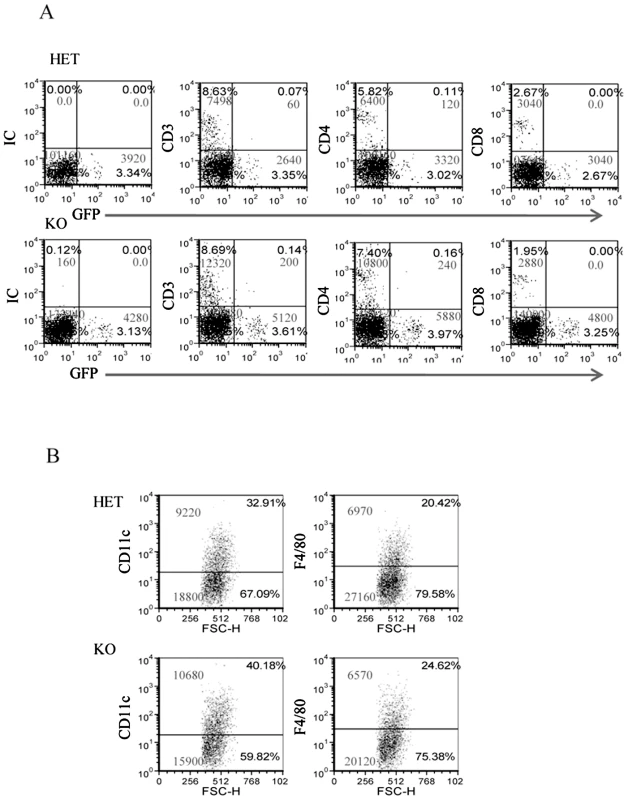

Immune cell accumulation in the infected chambers in the presence and in the absence of NCR1

To better characterize the immune cell populations present in the inflamed chambers and to investigate whether in the absence of NCR1 the percentage and the number of immune cells present in the chambers will be altered, we implanted chambers in the NCR1 knockout, Ncr1gfp/gfp mice (KO) and in the heterozygous, Ncr1+/gfp mice (HET, we used the Ncr1+/gfp mice because the heterozygous mice behaves similarity to the WT mice, but have an additional advantage as all NK and NK-like cells are GFP-positive, [21]). Since the NCR1 effect was observed 2 hours following F. nucleatum injection (see above figures) we inoculated the HET and KO mice with F. nucleatum and assayed for the presence of various immune cells two hours post infection.

Surprisingly, as can be seen in Figure 5, more lymphocytes had accumulated in the F. nucleatum infected chambers in the absence of NCR1 (the reasons for this are currently unknown). The T cell numbers (CD3+) were, in general, twice as large as the NK cell numbers and most of these T cells were helper CD4+ cells (Figure 5A). Macrophages (detected by F4/80+ staining) and DC (detected by CD11c staining) were also present in the chambers more or less at equal levels, irrespectively of whether NCR1 is present or is absent (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5. The infiltration of immune cells into the F. nucleatum challenged chambers is NCR1-independent.

The presence of immune cells; (A) lymphocytes and (B) DC (identified by CD11c) and macrophages (identified by F4/80) in the chambers were analyzed by FACS, 2 hours following the injection of F. nucleatum. The mAb used for staining is indicated in the Y axis. IC is isotype control. The percentage of the various cells and the cell numbers are indicated in each quadrant. One representative experiment out of four is shown. NCR1 and NKp46 directly interact with F. nucleatum

To test whether live bacteria is required for triggering the NCR1-mediated TNF-α secretion we repeated the in vivo chamber model experiments with heat-treated F. nucleatum. As seen in Figure 6A, 2 hours after inoculation with heat-killed F. nucleatum, the percentages of NK cells in the chambers were similar to those observed with the untreated, viable F. nucleatum (compare Figures 2 and 6). In contrast, 24 hours post inoculation, the percentages of NK cells in the chambers inoculated with the heat-killed F. nucleatum were not elevated (as observed with the untreated F. nucleatum, Figure 2), but rather stayed constant (Figure 6A).

Fig. 6. In vivo response to heat-treated F. nucleatum bacteria.

(A) FACS analysis of chamber exudates, 2 hours and 24 hours following challenge with heat-killed F. nucleatum. Staining was performed with Phycoerythrin conjugated anti-DX5 mAb. The percentages of GFP+ NK cells are indicated. One representative experiment out of three is shown. (B) TNF-α level in chamber exudates of Ncr1+/+ (WT) and Ncr1gfp/gfp (KO) was determined by ELISA, 2 and 24 hours following challenge with viable and heat-killed F. nucleatum. Data represent absorbance at 650 nm ± SD and are average of two different experiments. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. We next tested whether the TNF-α production will be affected by heat treatment. As can be seen in Figure 6B, a significant secretion of TNF-α was still detected following the inoculation of a heat-killed F. nucleatum bacteria (compared with the KO mice), however this TNF-α secretion was significantly less pronounced as compared with the F. nucleatum live bacteria. Thus, we concluded that heat treatment of the bacteria affects NK cell accumulation in the chamber and that it also slightly affects the NCR1-dependent TNFα secretion.

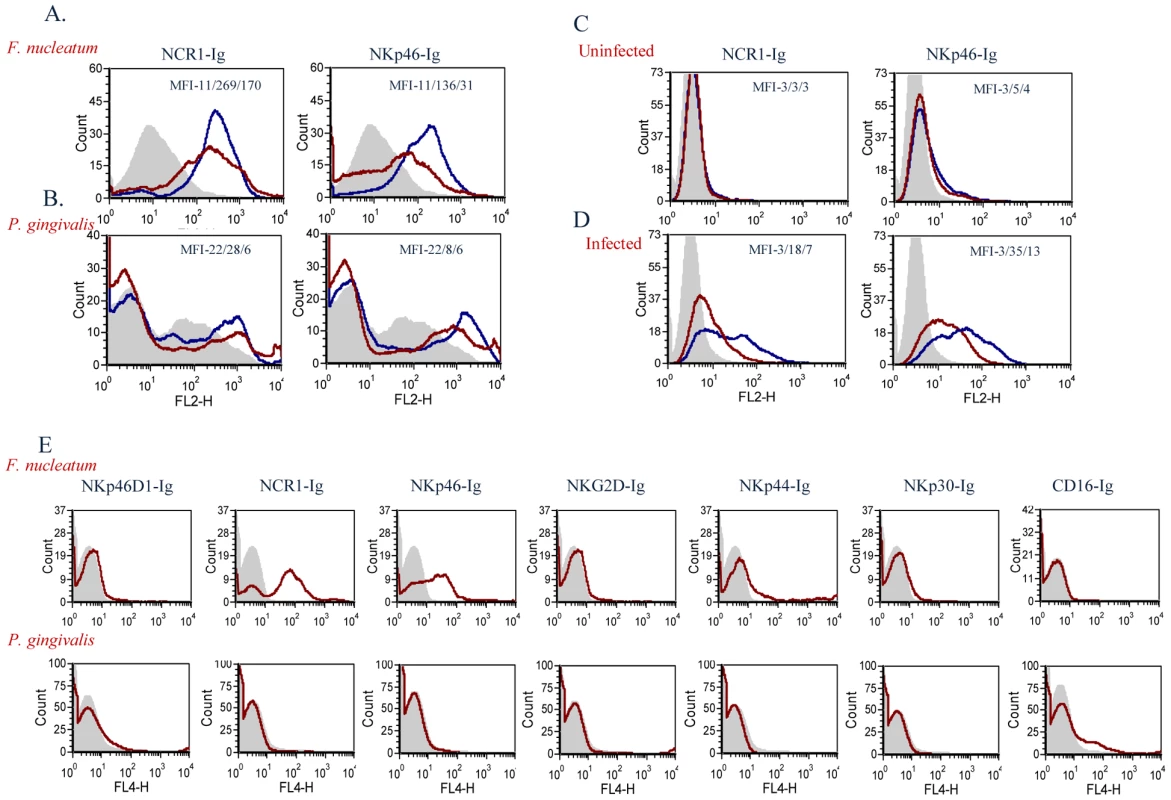

To test whether the mouse NCR1 and the human NKp46 directly interact with F. nucleatum we used fusion proteins (generated as previously described [17]), in which the extracellular domains of NCR1 and of NKp46 are fused to the Fc portion of human IgG1. As a negative control we used an Ig fusion protein made of the membrane proximal domain of NKp46 (named D1), that does not include the NKp46 site required for its binding [17], [21], [43]. Importantly, as can be seen in Figure 7A, a specific, dose dependent, binding of NCR1-Ig and NKp46-Ig was observed to F. nucleatum, whereas little or no binding was observed to P. gingivalis (Figure 7B).

Fig. 7. Direct binding of NCR1 and NKp46 to F. nucleatum.

F. nucleatum (A), P. gingivalis (B), uninfected 721.221 cells (C), and 721.221 cells infected with influenza PR8 virus (D), were stained with NCR1-Ig (left) and with NKp46-Ig (right) at two different dosages; 5 µg, blue line and 1 µg, red line. Staining was visualized using a Phycoerythrin conjugated anti-human Ig antibody. The filled grey histograms represent control staining with the NKp46D1-Ig fusion protein. The Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) values of the D1-Ig, NCR1-Ig and NKp46 staining are indicated in each of the histograms. One representative experiment out of five is shown. (E) F. nucleatum (upper) and P. gingivalis (lower) bacteria were stained with various activating NK cell receptors fused to Ig (indicated above the quadrants). Figure shows one representative experiment out of three performed. We have previously showed that NKp46 and NCR1 recognize influenza virus hemagglutinins [17], [21], [43]. To compare the efficiency of the interactions of NKp46 and NCR1 with F. nucleatum to that of hemagglutinin, we infected 721.221 cells with the PR8 influenza virus. As can be seen in Figure 7C, in the absence of infection little or no binding was observed when either NKp46-Ig or NCR1-Ig were used. In agreement with previous reports [17], [21], [43], following influenza infection, the binding of NKp46-Ig and NCR1-Ig was substantially increased (Figure 7D). The increased binding was dose-dependent (Figure 7) and was noticed with similar concentrations of fusion proteins that were used to detect binding to F. nucleatum.

For unknown reasons the P. gingivalis staining is sometimes observed as a smeared peak (Figure 7B) and sometimes appeared as a single peak (Figure 7E). Thus, to further demonstrate that the F. nucleatum recognition by NKp46/NCR1 is specific and that P. gingivalis is indeed not recognized by NKp46/NCR1 we stained the P. gingivalis and the F. nucleatum bacteria with various killer receptors fused to Ig. As can be seen in Figure 7E little or no staining of the Ig-fusion proteins (NKp46D1-Ig, NCR1-Ig, NKp46-Ig, NKG2D-Ig, NKp44-Ig, NKp30-Ig and CD16-Ig) was observed with the P. gingivalis, whereas F. nucleatum was recognized only by the human NKp46-Ig and its mouse orthologue NCR1-Ig (Figure 7E).

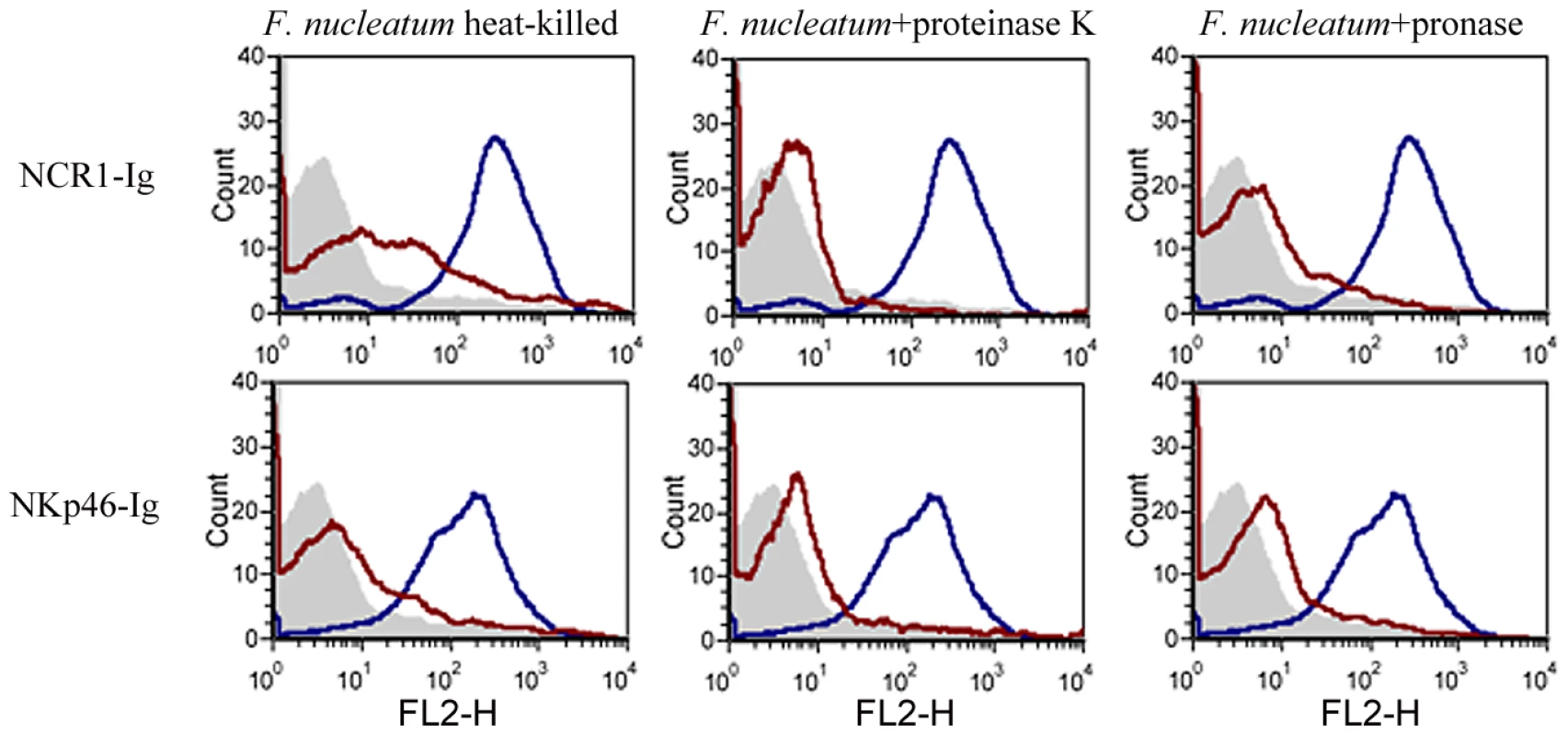

Binding of NCR1 and NKp46 to F. nucleatum is heat, proteinase K and pronase sensitive

We have previously shown that the recognition of influenza hemagglutinin by NCR1 and by NKp46 requires the sialylation of these receptors and that it is sensitive to digestion with neuroaminidase (NA) [17], [21], [43]. We therefore tested whether binding NCR1 and NKp46 to the unknown F. nucleatum ligand also involves sialic acid residues. For this, we treated the proteins with bacterial neuraminidase and observed that such treatment did not affect the binding to F. nucleatum (data not shown), suggesting that binding of NCR1 and NKp46 to the fusobacterial ligand is mechanistically different from the binding to viral hemagglutinins.

To further delineate the nature of the fusobacterial ligand, we tested the binding of NCR1-Ig and NKp46-Ig to heat-killed F. nucleatum, or to F. nucleatum that was treated with enzymes (proteinase K or pronase) known to modify proteins on bacterial surfaces. Because the proteinase K or pronase enzymes are active at 55°C we also tested whether NCR1-Ig and NKp46-Ig interact with F. nucleatum after heating the bacteria at 55°C for 1 hour and observed efficient binding (data not shown). Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1, all treatments did not affect the integrity or the presence of the bacteria.

Figure 8 shows that the F. nucleatum ligand is either a protein or a modification found on a protein, as heat, proteinase K and pronase treatments significantly reduced the binding of both the NCR1-Ig and the NKp46-Ig fusion proteins.

Fig. 8. The F. nucleatum ligand is sensitive to heat, proteinase K and pronase treatment.

Viable untreated, or treated (treatments are indicated above the histograms) F. nucleatum bacteria were stained with 5 µg of NCR1-Ig (upper) and of NKp46-Ig (lower). Filled grey histograms represent the staining with the NKp46D1-Ig. The blue histograms represent the staining of the untreated F. nucleatum and the red histograms represent the staining of the treated F. nucleatum. One representative experiment out of three is shown. The direct interaction between F. nucleatum and NCR1 is functional, resulting in TNF-α secretion

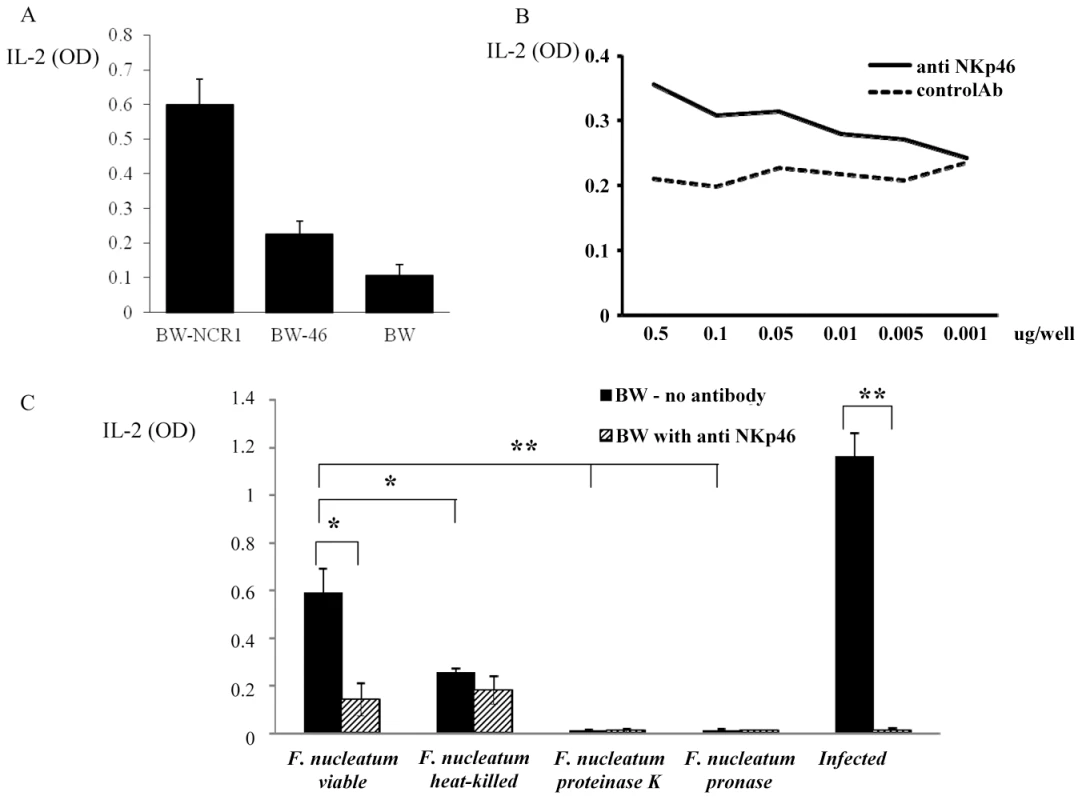

Next, we tested whether the direct interaction of F. nucleatum and NCR1 is functional. For this purpose, we initially used a reporter system in which we fused the NCR1 receptor to mouse CD3ζ chain and expressed this chimeric receptor in mouse BW cells. Triggering of this chimeric receptor will lead to the secretion of mouse IL-2, thus reporting for functional interaction of NCR1 with its ligand. However, upon generating this reporter system, a substantial secretion of IL-2 was observed, even without the addition of the bacteria (Figure 9A). A possible explanation to this observation is that the mouse BW cells express an unknown tumor ligand for the mouse NCR1 which consistently triggers IL-2 secretion as BW cells are specifically recognized by NCR1-Ig (data not shown).

Fig. 9. Functional reporter assays.

(A) Basal IL-2 secretion of BW-NCR1, BW-NKp46 and parental BW cells. (B) BW-NKp46 transfected cells were cultured for 48 h in presence of plate bound (dosages indicated in the X axis) anti NKp46 mAb and control mAb. (C) 5×104 BW-NKp46 transfected cells were cultured for 48 hours, with treated or untreated F. nucleatum and with 721.221 cells infected with PR8 influenza virus in the presence and in the absence of anti-NKp46 mAb. IL-2 secretion was determined by ELISA. Data represent absorbance at 650 nm ± SD and are average of two different experiments * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Because we demonstrated above that both the mouse NCR1 and the human NKp46 receptors directly interact with F. nucleatum, we next examined whether we could use the human NKp46 protein fused to zeta as our reporter system. Importantly, as can be seen in Figure 9A, the self-secretion of IL-2 from the BW-46 cells was much lower than that of BW-NCR1. Furthermore, the NKp46 reporter system was functional as triggering of NKp46-zeta on BW cells by using plate bound anti-NKp46 resulted in a dose dependent IL-2 secretion (Figure 9B).

Therefore, BW-46-zeta transfectants were incubated with viable F. nucleatum, with heat-killed F. nucleatum and with F. nucleatum treated with proteinase K or with pronase. PR8 influenza virus infected 721.221 cells were used as positive control (Figure 9C). Incubations were performed for 48 hours in the presence, or in the absence of anti-NKp46 mAb and IL-2 levels were measured in the supernatants. Figure 9C reveals that F. nucleatum induced a significant secretion of IL-2 from BW-NKp46 cells and this secretion was almost completely blocked by the anti-NKp46 mAb. Furthermore, (in agreement with the above binding results), heat-killed bacteria, or bacteria treated with proteinase K or with pronase induced little or no IL-2 secretion. The activation of this reporter system by hemagglutinin seems to be more efficient as compared with F. nucleatum as incubation of the BW-NKp46 cells with infected 721.221 cells resulted in pronounced IL-2 secretion.

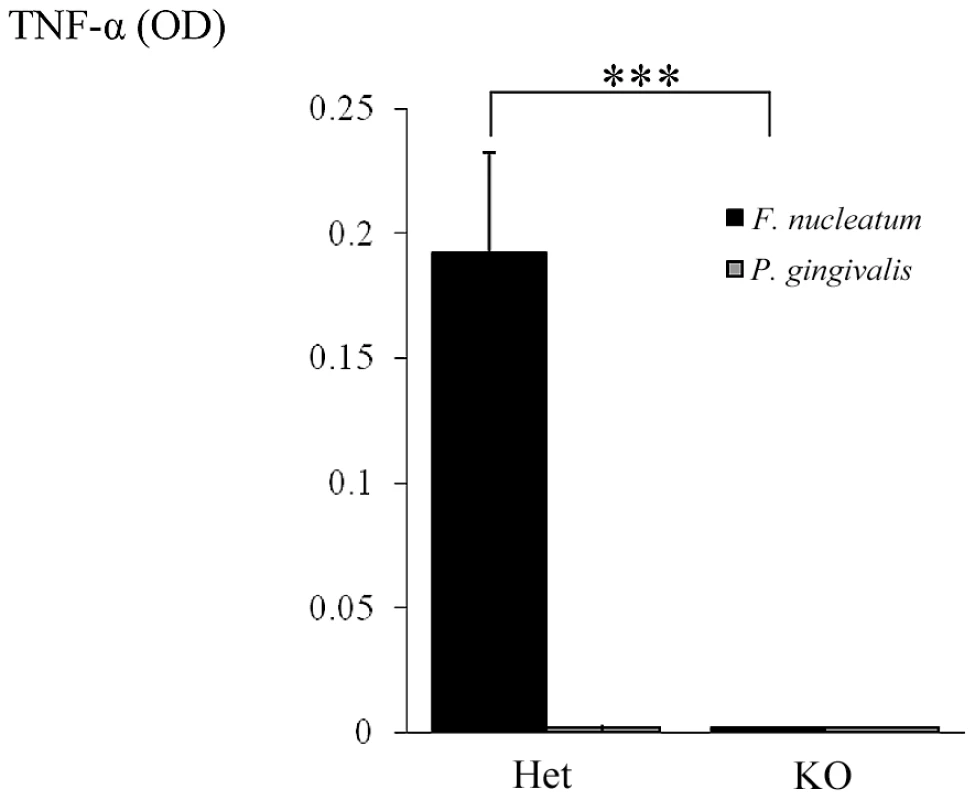

Our final effort was to demonstrate that the direct interaction between NCR1 and F. nucleatum will lead to TNF-α secretion. For this purpose we isolated (using the autoMACS instrument) mouse NK cells from Ncr1gfp/gfp and Ncr1+/gfp mice, incubated them with F. nucleatum or with P. gingivalis and tested the supernatants for the presence of TNF-α. As shown in Figure 10, no TNF-α secretion was observed when NK derived from the Ncr1gfp/gfp mice were incubated with F. nucleatum, while a significant secretion was detected when the Ncr1+/gfp mice were used. The TNF-α secretion was F. nucleatum-specific since P. gingivalis had no effect (Figure 10).

Fig. 10. NCR1-dependent secretion of TNF-α following interaction with F. nucleatum.

NK cells isolated from Ncr1+/gfp (Het) and from Ncr1gfp/gfp (KO) mice were cultured with F. nucleatum and with P. gingivalis bacteria for 48 hours. TNF-α secretion was determined by ELISA. Data represent absorbance at 650 nm ± SD and are average of two different experiments. *** p<0.001. Discussion

Periodontitis is a bacterial-induced inflammatory process that leads to the destruction of the tooth-supporting tissues and to tooth loss. It is one of the most common chronic inflammatory diseases in humans [44] and has been suggested as a risk factor for variable systemic conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis and preterm births [45]–[47].

Here we investigated whether NK cells are involved in periodontitis through the interaction between their specific NK receptor NKp46 with periodontal bacteria. We used two complementary animal models. In the first model we induced experimental periodontitis by orally infecting the Ncr1+/+ and Ncr1gfp/gfp animals with periodontal pathogenic bacteria. We show that in the absence of NCR1, when mice are infected with F. nucleatum, no loss of alveolar bone around the teeth is observed, while when mice were infected with P. gingivalis bone loss was observed independent of NCR1.

Due to technical and ethical limitations additional experiments could not be investigated in this model and we therefore used the subcutaneous chamber model [40], [41] to study the NKp46/NCR1 activity with regard to periodontal pathogens. Interestingly, we noticed that a large fraction of immune cells present in the inflamed chambers express NK cell markers such as NKG2D, DX5 and NK1.1, however these cells were not NK (GFP−), or T cells (CD3−). The identity and the function of these cells will be elucidated in future studies.

We show that in response to challenge with F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis, NK cells accumulate in the inflamed chambers, that F. nucleatum trigger the secretion of TNF-α and that the presence of TNF-α in the chambers is NCR1-dependent.

The interactions of NK cells with the bacteria probably renders them sensitive to in vitro manipulations and therefore we were not able to directly demonstrate that, in the chambers, NK cells are the main producers of TNF-α. Nevertheless, it is likely that TNF-α is indeed secreted by NK cells, in vivo, in response to F. nucleatum because upon incubation of isolated NK cells with F. nucleatum, an NCR1-dependent TNF-α secretion is observed.

Because alveolar bone loss is observed following P. gingivalis infection and since TNF-α could hardly be detected in the chambers following P. gingivalis infection we suggest that TNF-α has little role in the induction of the P. gingivalis-mediated bone loss in the system we used.

TNF-α is a very potent proinflammatory cytokine having pleotropic effects on both the immune and the skeletal systems. Its role and its contribution to the pathogenesis of chronic periodontitis, tissue destruction and bone loss has been clearly documented [48]–[50] and administration of anti-TNF-α antibodies resulted in reduced alveolar bone loss [51]–[54].

Previous studies demonstrated that the direct recognition of tumor cells [21], [43], viral infected cells [17], [43] and beta cells [20] by NKp46 (NCR1) lead to killing and to the secretion of TNF-α and IFN-γ [22], [55]–[57]. In our experimental system TNF-α, but not IFN-γ was present in the chambers. Similar observations were noted in other studies and it was proposed that NK cells shape their functional phenotype depending on the nature of the stimuli. For example, some tumors were able to induce TNF-α, but not IFN-γ secretion when co-cultured with naïve NK cells and only when NK cells were activated with IL-2, a significant increase in IFN-γ could be seen [58]. Another study showed that IL-4 compromised the ability of stimulated NK cells to release IFN-γ, without affecting the secretion of TNF-α [15] and interestingly IL-4 was detected in the chambers' exudates (data not shown).

The TNF-α response to F. nucleatum was NCR1-dependant, however, in the chamber experiments, in the absence of NCR1, the TNF-α secretion was markedly reduced but not totally abrogated. In contrast, no TNF-α secretion was observed from purified NK cells lacking NCR1 that interacted with F. nucleatum. This suggests that in the chambers, cells other than NK cells probably provide additional source for TNF-α. Indeed, previous studies showed that F. nucleatum-derived lipopolysaccharide up-regulated the secretion of the TNF-α by macrophage-like cells [59]. As shown here, macrophages and DCs are also present in the F. nucleatum-inflamed chambers and therefore we can speculate that the low level of TNF-α observed in the chambers implanted in the NCR1gfp/gfp animals is released either by macrophages recruited into the chambers, or by other immune cells.

Twenty four hours following bacteria inoculation, the TNF-α levels dramatically dropped to almost baseline levels, in spite of the continuous accumulation of NK cells in the chambers. This transient nature of TNF-α response has been reported previously [60], [61] and we assume that the TNF-α levels decline due to the elimination of F. nucleatum (the stimulating antigen) from the chambers during the study period.

In summary, we provide here the first evidence that NKp46 and NCR1 directly recognize a periodontal pathogen and we show that this recognition is heat, proteinase K and pronase sensitive, suggesting that the bacterial ligand is a protein or modifications of protein. Our data support the idea that periodontal pathogens initiate the disease by activating host mechanisms that consequently contribute to the destruction of the supporting apparatus of the periodontium by releasing inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of the Ncr1gfp/gfp knockout mice has been previously described [21]. All experiments were performed in the specific pathogen–free unit of Hadassah Medical School (Ein-Kerem, Jerusalem) according to guidelines of the ethical committee. Ethics statement: This study was carried out in strict accordance with the Law for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (1994) and the regulations of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Ethics Committee for Maintenance and Experimentation on Laboratory Animals. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Permit Number: 11-5413). All surgery was performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

P. gingivalis strain ATCC3327 and F. nucleatum strain PK1594 were grown in an Bactron II anaerobic (N2∶CO2∶H2, 90∶5∶5) chamber (Sheldon Manufacturing Inc., Cornelius, OR) at 37°C in Wilkins-Chalgran anaerobic broth (Fluka, Spain) anaerobic chamber. E. coli strain ATCC25922 was grown in LB broth (Lennox, BD, Maryland, USA). Bacterial purity was determined by phase contrast microscopy. Bacteria were harvested during the logarithmic phase, washed by centrifugation and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 107 bacteria/ml [40], [62]. Heat-killing was performed at 100°C for 10 min.

Experimental periodontitis model

Infection was carried out as described by Baker at al. 2000 and Wilensky et al. 2009 [63], [64]. In brief, four to five-week-old Ncr1+/+ (WT) and Ncr1gfp/gfp (KO) mice were given sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 0.08% and 0.016% respectively, in drinking water, ad libitum for 10 days. Three days following the withdrawal of antibiotics (day 14), the animals were infected with F. nucleatum or with P. gingivalis (2×108 CFU in 0.2 ml of PBS and 2% carboxymethylcellulose) or vehicle only. The infection was carried out by gavage into the esophagus and oral cavity 3 times, once every other day. Forty two days after the last infection, the mice were sacrificed and the hemi-maxillae were collected and prepared for bone loss measurements using the micro computerized-tomography (μCT) technique [38]. At the end of the experiments mice were killed by CO2.

Quantification of alveolar bone loss

For quantitative 3-dimensional analysis of the alveolar bone loss, the hemi-maxillae were examined by a desktop micro-CT system (μCT 40, Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The sagittal plan of the specimens was set parallel to the X-ray beam axis. The specimens were scanned at a resolution of 12 µm in all 3 spatial dimensions. The scans were Gaussian-filtered and segmented using a multi-level global thresholding procedure for the segmentation of enamel, dentin and bone. Residual supportive bone volume (RSBV) was determined separately for either root (bucco-mesial and bucco-distal) using a direct 3-dimensional approach [65]. The measured mesio-distal length of the alveolar bone was 204 µm and 120 µm for the mesio-buccal and the disto-buccal roots, respectively. The apical basis of the measured volume was set mesio-distally parallel to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and bucco-palatinally parallel to the occlusal plane. The results represented the residual bone above the reference plane in mm3 [38].

Subcutaneous chamber model

Two titanium coil chambers were inserted subcutaneously into anesthetized 6–8 week-old male mice as previously described [41]. After 10–14 days, the chambers were thoroughly emptied of their exudates and P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum and E. coli (106 bacteria in 100 µl of PBS) were immediately injected into each chamber. The exudates were collected at 2 and 24 h post-infection (each chamber was sampled only once). After centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min, the supernatants were collected for bacterial counts and cytokine analysis. To remove red blood cells the pellets were re-suspended in 3 ml of cold lysis buffer containing NH4Cl (1.55M), KHCO3 (0.138M) and NaEDTA (0.684 mM) at pH 7.3 for 3 min, after which the cells were washed and re-suspended in 0.5% BSA/PBS for flow cytometry analysis.

Flow cytometry

Antibodies specific for NK cells (DX5; Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), NKG2D (CX5; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) were conjugated to phycoerythrin. DC were identified by CD11c (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), macrophage with F4/80 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) and T cells were stained with CD3, CD4 and CD8 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). NK1.1 antibody was produced in PK136 hybridoma cell line, as previously described [66]. Staining of NK1.1 was visualized with a secondary Cy5-conjugated strepavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). For intracellular staining cells were washed with Perm Wash (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), fixed and treated with Brefeldin A (Cell Signaling Technology) for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with antibodies to TNF-α (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Cytokine analysis

The levels of TNF-α in chamber exudates were determined by ELISA as previously described [67].

Determining the presence of viable bacteria in the chambers

Ten microliters of chamber exudates was serially diluted in duplicates in PBS and plated on tryptic soy agar containing sheep blood (Hylabs, Rehovot, IL). Plates with exudates from chambers challenged with P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum were grown under anaerobic conditions for 5–7 days at 37°C, while plates with exudates from E. coli challenged mice were grown in aerobic conditions at 37°C for 24 hours. The bacteria in the different colonies were identified by phase contrast microscopy. In addition, P. gingivalis colonies were confirmed by their black pigment.

Staining of bacteria with soluble fusion proteins

The generation of NCR1-Ig, NKp46-Ig, NKp46D1-Ig, NKp44, NKG2D, NKp30 and CD16 was previously described [17], [18]. Proteins were purified on protein A/G columns as previously described [17], [18]. 2×105 bacteria were stained with 5 µg fusion proteins (unless indicated otherwise). Staining was performed in the absence of azid and was visualized using a Phycoerythrin or Allophycocyanin conjugated anti-human Ig antibody.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) release assays from mouse lymphoma BW cells transfectants

Generation of the stable transfectants BW-NCR1 and BW-NKp46 was previously described [17]. 105 treated and untreated F. nucleatum and 5×104 influenza PR8-infected or uninfected 721.221 cells were incubated with 5×104 BW-NKp46 cells in the presence and in the absence of 0.5 µg/well anti-NKp46 mAb (generated in our laboratory). All assays were performed in medium that do not contain antibiotics, at 37°C for 48 hours. The presence of IL-2 was measured by ELISA kit (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

TNF-α release assays from freshly-isolated NK cells

NK cells were isolated from splenocytes obtained from Ncr1+/gfp and from the Ncr1gfp/gfp mice by using an NK isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA).The percentage of GFP+ cells was assessed by FACS and 5×104 NK cells were cultured with 105 F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis bacteria for 48 hours at 37°C. The presence of TNF-α was determined by ELISA.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AlbandarJMBrunelleJAKingmanA 1999 Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988–1994. J Periodontol 70 13 29

2. WuTTrevisanMGencoRJDornJPFalknerKL 2000 Periodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: the first national health and nutrition examination survey and its follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 160 2749 2755

3. ScannapiecoFA 1999 Role of oral bacteria in respiratory infection. J Periodontol 70 793 802

4. OffenbacherSJaredHLO'ReillyPGWellsSRSalviGE 1998 Potential pathogenic mechanisms of periodontitis associated pregnancy complications. Ann Periodontol 3 233 250

5. DodmanTRobsonJPincusD 2000 Kingella kingae infections in children. J Paediatr Child Health 36 87 90

6. BerbariEFCockerillFR3rdSteckelbergJM 1997 Infective endocarditis due to unusual or fastidious microorganisms. Mayo Clin Proc 72 532 542

7. BeckJGarciaRHeissGVokonasPSOffenbacherS 1996 Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol 67 1123 1137

8. de PabloPChappleILBuckleyCDDietrichT 2009 Periodontitis in systemic rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 5 218 224

9. WegnerNWaitRSrokaAEickSNguyenKA 2010 Peptidylarginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis citrullinates human fibrinogen and alpha-enolase: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 62 2662 2672

10. Van DykeTELesterMAShapiraL 1993 The role of the host response in periodontal disease progression: implications for future treatment strategies. J Periodontol 64 792 806

11. MorettaLBottinoCPendeDVitaleMMingariMC 2005 Human natural killer cells: Molecular mechanisms controlling NK cell activation and tumor cell lysis. Immunol Lett 100 7 13

12. LanierLL 2005 NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 23 225 274

13. ArnonTIMarkelGMandelboimO 2006 Tumor and viral recognition by natural killer cells receptors. Semin Cancer Biol 16 348 358

14. BiassoniRCantoniCPendeDSivoriSParoliniS 2001 Human natural killer cell receptors and co-receptors. Immunol Rev 181 203 214

15. MarcenaroEDella ChiesaMBelloraFParoliniSMilloR 2005 IL-12 or IL-4 prime human NK cells to mediate functionally divergent interactions with dendritic cells or tumors. J Immunol 174 3992 3998

16. RauletDH 2003 Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol 3 781 790

17. MandelboimOLiebermanNLevMPaulLArnonTI 2001 Recognition of haemagglutinins on virus-infected cells by NKp46 activates lysis by human NK cells. Nature 409 1055 1060

18. ArnonTILevMKatzGChernobrovYPorgadorA 2001 Recognition of viral hemagglutinins by NKp44 but not by NKp30. Eur J Immunol 31 2680 2689

19. ArnonTIAchdoutHLeviOMarkelGSalehN 2005 Inhibition of the NKp30 activating receptor by pp65 of human cytomegalovirus. Nat Immunol 6 515 523

20. GurCPorgadorAElboimMGazitRMizrahiS 2010 The activating receptor NKp46 is essential for the development of type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol 11 121 128

21. GazitRGrudaRElboimMArnonTIKatzG 2006 Lethal influenza infection in the absence of the natural killer cell receptor gene Ncr1. Nat Immunol 7 517 523

22. ElboimMGazitRGurCGhadiallyHBetser-CohenG 2010 Tumor immunoediting by NKp46. J Immunol 184 5637 5644

23. OrangeJS 2002 Human natural killer cell deficiencies and susceptibility to infection. Microbes Infect 4 1545 1558

24. LoriniRMorettaAValtortaAd'AnnunzioGCortonaL 1994 Cytotoxic activity in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 23 37 42

25. ZeidelABeilinBYardeniIMayburdESmirnovG 2002 Immune response in asymptomatic smokers. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 46 959 964

26. LundgrenTParharRSRenvertSTatakisDN 2005 Impaired cytotoxicity in Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J Dent Res 84 414 417

27. BakerPJDixonMEvansRTDufourLJohnsonE 1999 CD4(+) T cells and the proinflammatory cytokines gamma interferon and interleukin-6 contribute to alveolar bone loss in mice. Infect Immun 67 2804 2809

28. GorskaRGregorekHKowalskiJLaskus-PerendykASyczewskaM 2003 Relationship between clinical parameters and cytokine profiles in inflamed gingival tissue and serum samples from patients with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 30 1046 1052

29. JewettAGanXHLebowLTBonavidaB 1996 Differential secretion of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma by human peripheral blood-derived NK subsets and association with functional maturation. J Clin Immunol 16 46 54

30. VarmaTKLinCYToliver-KinskyTESherwoodER 2002 Endotoxin-induced gamma interferon production: contributing cell types and key regulatory factors. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 9 530 543

31. AgerberthBCharoJWerrJOlssonBIdaliF 2000 The human antimicrobial and chemotactic peptides LL-37 and alpha-defensins are expressed by specific lymphocyte and monocyte populations. Blood 96 3086 3093

32. ChalifourAJeanninPGauchatJFBlaeckeAMalissardM 2004 Direct bacterial protein PAMP recognition by human NK cells involves TLRs and triggers alpha-defensin production. Blood 104 1778 1783

33. PutsepKCarlssonGBomanHGAnderssonM 2002 Deficiency of antibacterial peptides in patients with morbus Kostmann: an observation study. Lancet 360 1144 1149

34. LuQJinLDarveauRPSamaranayakeLP 2004 Expression of human beta-defensins-1 and -2 peptides in unresolved chronic periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 39 221 227

35. StashenkoPJandinskiJJFujiyoshiPRynarJSocranskySS 1991 Tissue levels of bone resorptive cytokines in periodontal disease. J Periodontol 62 504 509

36. GravesDTCochranD 2003 The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. J Periodontol 74 391 401

37. Van DykeTEKornmanKS 2008 Inflammation and factors that may regulate inflammatory response. J Periodontol 79 1503 1507

38. WilenskyAGabetYYumotoHHouri-HaddadYShapiraL 2005 Three-dimensional quantification of alveolar bone loss in Porphyromonas gingivalis-infected mice using micro-computed tomography. J Periodontol 76 1282 1286

39. PolakDWilenskyAShapiraLHalabiAGoldsteinD 2009 Mouse model of experimental periodontitis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis/Fusobacterium nucleatum infection: bone loss and host response. J Clin Periodontol 36 406 410

40. GencoCAArkoRJ 1994 Animal chamber models for study of host-parasite interactions. Methods Enzymol 235 120 140

41. Houri-HaddadYSoskolneWAHalabiABarakVShapiraL 2000 Repeat bacterial challenge in a subcutaneous chamber model results in augmented tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma response, and suppression of interleukin-10. Immunology 99 215 220

42. Houri-HaddadYSoskoineWAShapiraL 2001 Immunization to Porphyromonas gingivalis enhances the local pro-inflammatory response to subcutaneous bacterial challenge. J Clin Periodontol 28 476 482

43. ArnonTIAchdoutHLiebermanNGazitRGonen-GrossT 2004 The mechanisms controlling the recognition of tumor - and virus-infected cells by NKp46. Blood 103 664 672

44. AlbandarJM 2005 Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am 49 517 532 v–vi

45. SeymourGJFordPJCullinanMPLeishmanSYamazakiK 2007 Relationship between periodontal infections and systemic disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 13 Suppl 4 3 10

46. HanYWFardiniYChenCIacampoKGPerainoVA 2010 Term stillbirth caused by oral Fusobacterium nucleatum. Obstet Gynecol 115 442 445

47. MooreWEMooreLV 1994 The bacteria of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 5 66 77

48. OkadaHMurakamiS 1998 Cytokine expression in periodontal health and disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 9 248 266

49. SchettGSteinerCWXuQSmolenJSSteinerG 2003 TNFalpha mediates susceptibility to heat-induced apoptosis by protein phosphatase-mediated inhibition of the HSF1/hsp70 stress response. Cell Death Differ 10 1126 1136

50. ShealyDJWooleyPHEmmellEVolkARosenbergA 2002 Anti-TNF-alpha antibody allows healing of joint damage in polyarthritic transgenic mice. Arthritis Res 4 R7

51. AssumaROatesTCochranDAmarSGravesDT 1998 IL-1 and TNF antagonists inhibit the inflammatory response and bone loss in experimental periodontitis. J Immunol 160 403 409

52. GravesDTDelimaAJAssumaRAmarSOatesT 1998 Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor antagonists inhibit the progression of inflammatory cell infiltration toward alveolar bone in experimental periodontitis. J Periodontol 69 1419 1425

53. NakashimaTKobayashiYYamasakiSKawakamiAEguchiK 2000 Protein expression and functional difference of membrane-bound and soluble receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand: modulation of the expression by osteotropic factors and cytokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 275 768 775

54. KobayashiKTakahashiNJimiEUdagawaNTakamiM 2000 Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism independent of the ODF/RANKL-RANK interaction. J Exp Med 191 275 286

55. SivoriSPendeDBottinoCMarcenaroEPessinoA 1999 NKp46 is the major triggering receptor involved in the natural cytotoxicity of fresh or cultured human NK cells. Correlation between surface density of NKp46 and natural cytotoxicity against autologous, allogeneic or xenogeneic target cells. Eur J Immunol 29 1656 1666

56. MorettaABottinoCVitaleMPendeDCantoniC 2001 Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol 19 197 223

57. HannaJGoldman-WohlDHamaniYAvrahamIGreenfieldC 2006 Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med 12 1065 1074

58. Romero-ReyesMHeadCCacalanoNAJewettA 2007 Potent induction of TNF-alpha during interaction of immune effectors with oral tumors as a potential mechanism for the loss of NK cell viability and function. Apoptosis 12 2063 2075

59. GrenierDGrignonL 2006 Response of human macrophage-like cells to stimulation by Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp. nucleatum lipopolysaccharide. Oral Microbiol Immunol 21 190 196

60. Houri-HaddadYSoskolneWAShaiEPalmonAShapiraL 2002 Interferon-gamma deficiency attenuates local P. gingivalis-induced inflammation. J Dent Res 81 395 398

61. BurnsEBachrachGShapiraLNussbaumG 2006 Cutting Edge: TLR2 is required for the innate response to Porphyromonas gingivalis: activation leads to bacterial persistence and TLR2 deficiency attenuates induced alveolar bone resorption. J Immunol 177 8296 8300

62. KolenbranderPEAndersenRN 1989 Inhibition of coaggregation between Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis by lactose and related sugars. Infect Immun 57 3204 3209

63. BakerPJDixonMEvansRTRoopenianDC 2000 Heterogeneity of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains in the induction of alveolar bone loss in mice. Oral Microbiol Immunol 15 27 32

64. WilenskyAPolakDAwawdiSHalabiAShapiraL 2009 Strain-dependent activation of the mouse immune response is correlated with Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced experimental periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 36 915 921

65. HildebrandTLaibAMullerRDequekerJRuegseggerP 1999 Direct three-dimensional morphometric analysis of human cancellous bone: microstructural data from spine, femur, iliac crest, and calcaneus. J Bone Miner Res 14 1167 1174

66. KooGCDumontFJTuttMHackettJJrKumarV 1986 The NK-1.1(-) mouse: a model to study differentiation of murine NK cells. J Immunol 137 3742 3747

67. FrolovIHouri-HadadYSoskolneAShapiraL 1998 In vivo exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis up-regulates nitric oxide but suppresses tumour necrosis factor-alpha production by cultured macrophages. Immunology 93 323 328

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 3- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- An Entomopathogenic Nematode by Any Other Name

- Induced Release of a Plant-Defense Volatile ‘Deceptively’ Attracts Insect Vectors to Plants Infected with a Bacterial Pathogen

- A Foot in the Door for Dermatophyte Research

- New Insights into spp.: A Potential Link with Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Indifferent, Affectionate, or Deceitful: Lifestyles and Secretomes of Fungi

- Mutation and Selection of Prions

- Sleeping with the Enemy: How Intracellular Pathogens Cope with a Macrophage Lifestyle

- Taste for Blood: Hemoglobin as a Nutrient Source for Pathogens

- Direct Recognition of by the NK Cell Natural Cytotoxicity Receptor NKp46 Aggravates Periodontal Disease

- A20 () Deficiency in Myeloid Cells Protects against Influenza A Virus Infection

- Anthrax Lethal Factor Cleavage of Nlrp1 Is Required for Activation of the Inflammasome

- Differential Function of Lip Residues in the Mechanism and Biology of an Anthrax Hemophore

- PK-sensitive PrP Is Infectious and Shares Basic Structural Features with PK-resistant PrP

- A Peptidoglycan Fragment Triggers β-lactam Resistance in

- Capsule Type of Determines Growth Phenotype

- Additive Function of MARTX and VvhA Cytolysins Promotes Rapid Growth and Epithelial Tissue Necrosis During Intestinal Infection

- A Novel Mouse Model of Egg-Induced Immunopathology

- Redundant Notch1 and Notch2 Signaling Is Necessary for IFNγ Secretion by T Helper 1 Cells During Infection with

- The Novel Transporter Dur31 Is a Multi-Stage Pathogenicity Factor

- Short ORF-Dependent Ribosome Shunting Operates in an RNA Picorna-Like Virus and a DNA Pararetrovirus that Cause Rice Tungro Disease

- Structural Insights into a Unique Effector LidA Recognizing Both GDP and GTP Bound Rab1 in Their Active State

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Foot in the Door for Dermatophyte Research

- Structural Insights into a Unique Effector LidA Recognizing Both GDP and GTP Bound Rab1 in Their Active State

- An Entomopathogenic Nematode by Any Other Name

- New Insights into spp.: A Potential Link with Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání