-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaInsertion of an Esterase Gene into a Specific Locust Pathogen () Enables It to Infect Caterpillars

An enduring theme in pathogenic microbiology is poor understanding of the mechanisms of host specificity. Metarhizium is a cosmopolitan genus of invertebrate pathogens that contains generalist species with broad host ranges such as M. robertsii (formerly known as M. anisopliae var. anisopliae) as well as specialists such as the acridid-specific grasshopper pathogen M. acridum. During growth on caterpillar (Manduca sexta) cuticle, M. robertsii up-regulates a gene (Mest1) that is absent in M. acridum and most other fungi. Disrupting M. robertsii Mest1 reduced virulence and overexpression increased virulence to caterpillars (Galleria mellonella and M. sexta), while virulence to grasshoppers (Melanoplus femurrubrum) was unaffected. When Mest1 was transferred to M. acridum under control of its native M. robertsii promoter, the transformants killed and colonized caterpillars in a similar fashion to M. robertsii. MEST1 localized exclusively to lipid droplets in M. robertsii conidia and infection structures was up-regulated during nutrient deprivation and had esterase activity against lipids with short chain fatty acids. The mobilization of stored lipids was delayed in the Mest1 disruptant mutant. Overall, our results suggest that expression of Mest1 allows rapid hydrolysis of stored lipids, and promotes germination and infection structure formation by M. robertsii during nutrient deprivation and invasion, while Mest1 expression in M. acridum broadens its host range by bypassing the regulatory signals found on natural hosts that trigger the mobilization of endogenous nutrient reserves. This study suggests that speciation in an insect pathogen could potentially be driven by host shifts resulting from changes in a single gene.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002097

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002097Summary

An enduring theme in pathogenic microbiology is poor understanding of the mechanisms of host specificity. Metarhizium is a cosmopolitan genus of invertebrate pathogens that contains generalist species with broad host ranges such as M. robertsii (formerly known as M. anisopliae var. anisopliae) as well as specialists such as the acridid-specific grasshopper pathogen M. acridum. During growth on caterpillar (Manduca sexta) cuticle, M. robertsii up-regulates a gene (Mest1) that is absent in M. acridum and most other fungi. Disrupting M. robertsii Mest1 reduced virulence and overexpression increased virulence to caterpillars (Galleria mellonella and M. sexta), while virulence to grasshoppers (Melanoplus femurrubrum) was unaffected. When Mest1 was transferred to M. acridum under control of its native M. robertsii promoter, the transformants killed and colonized caterpillars in a similar fashion to M. robertsii. MEST1 localized exclusively to lipid droplets in M. robertsii conidia and infection structures was up-regulated during nutrient deprivation and had esterase activity against lipids with short chain fatty acids. The mobilization of stored lipids was delayed in the Mest1 disruptant mutant. Overall, our results suggest that expression of Mest1 allows rapid hydrolysis of stored lipids, and promotes germination and infection structure formation by M. robertsii during nutrient deprivation and invasion, while Mest1 expression in M. acridum broadens its host range by bypassing the regulatory signals found on natural hosts that trigger the mobilization of endogenous nutrient reserves. This study suggests that speciation in an insect pathogen could potentially be driven by host shifts resulting from changes in a single gene.

Introduction

An enduring theme in pathogenic microbiology is poor understanding of the mechanisms of host specificity. That is, what factors limit a pathogens host range, how is host specificity linked with virulence and what changes in pathogens or hosts can open new host ranges? These are fundamental questions that relate both to the co-evolution of host susceptibility and pathogen virulence, as well as to factors underlying host switching and the emergence of new pathogens that originate in different host species. The molecular mechanisms controlling host selectivity in fungi are particularly poorly understood. A number of plant pathogenic fungi produce secondary metabolites with biological specificities that correspond with the host range of the producing fungi [1], [2], and small secreted proteins produced by the pathogen can trigger resistance in some plants limiting host range [3]. However, to date these have not been found in animal pathogenic fungi, many of which seem to be broadly opportunistic. This has allowed researchers on emergent human pathogenic fungi to employ insects as model systems [4]. Most human pathogens are not normally transmitted between insect hosts. However, specialization to entomopathogenicity is a major fungal lifestyle with ∼1000 known species that can be highly infectious. In contrast to the opportunistic pathogens, many of these have evolved narrow host ranges by as yet unknown mechanisms.

Metarhizium is a cosmopolitan genus of Ascomycetes (class Sordariomycetes) comprising species that exhibit varied lifestyles. Metarhizium robertsii (formerly known as M. anisopliae var. anisopliae [5]) is a generalist able to infect hundreds of insect species. It has been at the forefront of efforts to develop biocontrol alternatives to chemical insecticides in agricultural and human disease-vector control programs [6]–[8]. M. robertsii has also been used to study the interactions between invertebrate model hosts and pathogenic fungi as host innate immune responses are broadly conserved across many phyla [9]. In contrast M. acridum is a specialist with a narrow host range for certain locusts and grasshoppers [10]. This specificity is one of the reasons it is being mass produced as an environmentally safe alternative to pesticides [10]–[12].

The infection strategies of Metarhizium species resemble those of most plant pathogens. Infection proceeds via spores that adhere to the host surface and germinate to form a germ tube that continues undifferentiated hyphal growth if nutrient quality and quantity are not conducive for differentiation of infection structures. On a host, however, apical elongation terminates and germ tubes produce infection structures, called appressoria, which promote the localized production of cuticle degrading enzymes and also build up turgor providing a mechanical component to penetration [13]–[15]. The formation of appressoria by broad host range strains of M. robertsii such as ARSEF2575 (Mr2575) can also be induced efficiently by low levels of complex nitrogenous nutrients [13]. However, pathogens with a narrow host range such as M. acridum ARSEF324 (Ma324) ( = CSIRO FI 485: the active ingredient of ‘Green Guard’) germinate poorly under these conditions and only produce abundant appressoria in the presence of a lipid extract from host insects [16].

M. robertsii Mr2575 sharply up-regulates the Mest1 gene when germinating on insect cuticles [17]. This gene is absent in Ma324 [18], which suggests that it is unlikely to have an essential function in the related M. robertsii but we speculated that it might have a niche role in pathogenicity, perhaps facilitating an opportunistic life-style. In this study, we functionally characterized MEST1 and demonstrated that inserting Mest1 into M. acridum is sufficient to expand its host range to include lepidopterans. Mest1 is thus the first gene identified in an entomopathogenic fungus that encodes a determinant of specificity and is to our knowledge the first example where a single metabolic protein assumes such a crucial role for host selectivity in a animal pathogenic fungus. We speculate that speciation in insect pathogens can be driven by host shifts that become fixed in populations due to the gain or loss of a pathogen gene that confers wide host specificity.

Results

Gene cloning, molecular characterization and gene disruption of Mest1

The M. robertsii Mest1 is 1188 bp long and lacks introns. It encodes a predicted protein of 395 amino acids, with a deduced molecular weight of 42244 Da and a pI of 5.34. The SignalP 3.0 program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) revealed no signal sequence suggesting that MEST1 is a cell-bound protein. MEST1 contains the sequence GGS341VG which conforms to the motif G-X1-S-X2-G, commonly observed in serine esterases and many lipases [19]–[21]. According to M. robertsii genome sequence data [22], Mest1 (MAA_03283) is downstream of three secreted cuticle degrading subtilisins (Pr1F (MAA_03280), Pr1E (MAA_03281) and a subtilisin-like protease (MAA_03282). The M. robertsii genome also contains a paralog (MAA_08059) with 42% identity to MEST1 that is downstream of three hypothetical proteins and upstream of a glutathione S-transferase. The genome of M. acridum strain CQMa 102 lacks an ortholog of MEST1 but contains a sequence (MAC_02852) with 90.2% identity to MAA_08059 (the median sequence identity of orthologs is 89.8%). MAC_02852 is downstream of four hypothetical proteins and upstream of glutathione S-transferase indicating that it is syntenic with its ortholog MAA_08059.

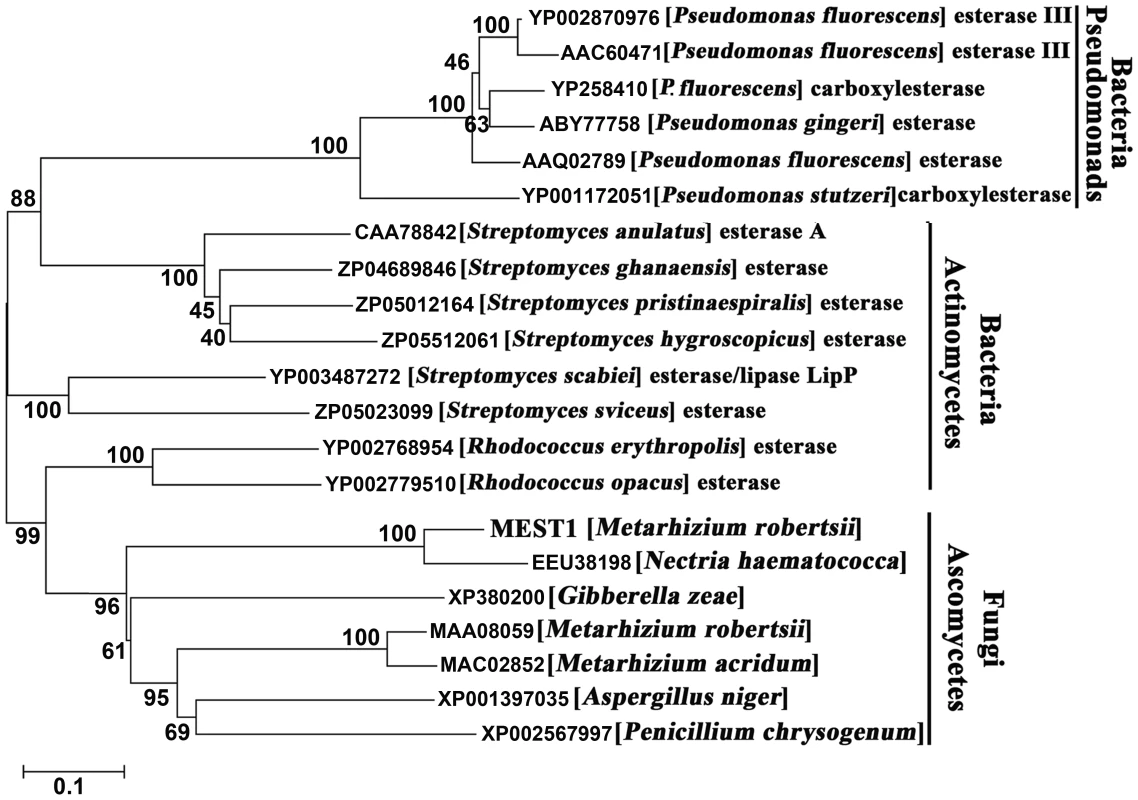

Homologs to MEST1 and MAA_08059 were identified in four other ascomycete fungi, but only the related Nectria haematococca had a sequence (EEU_38198) that was highly similar (82% identity) to MEST1. The related Gibberella zeae (XP_380200) as well as Aspergillus niger (XP_001397035) and Penicillium chrysogenum (XP_002567997) contain single copy sequences resembling MAA_08059 (Figure 1). The functions of these genes have not been reported and contain a putative penicillin-binding domain characteristic of β-lactamase class C proteins. Homologs of MEST1 were absent in Neurospora crassa, Magnaporthe grisea, Schizosaccharomyces japonicus, Trichoderma harzianum and T. reesei, as well as Basidiomycetes, Zygomycetes and Chytridiomycetes. However, MEST1 shows up to 42% identity with bacterial sequences, including known esterases [19]. A phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) confirmed that MEST1 and the fungal homologs formed a separate well supported clade distinct from bacterial clades containing actinomycete and pseudomonad sequences.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic relationship of MEST1 with its homologs.

The amino acid sequences were aligned with Clustal X and a neighbor-joining tree was generated with 1,000 boot strap replicates using the program MEGA v4.0. MEST1 regulates virulence and appressorial differentiation in Metarhizium robertsii

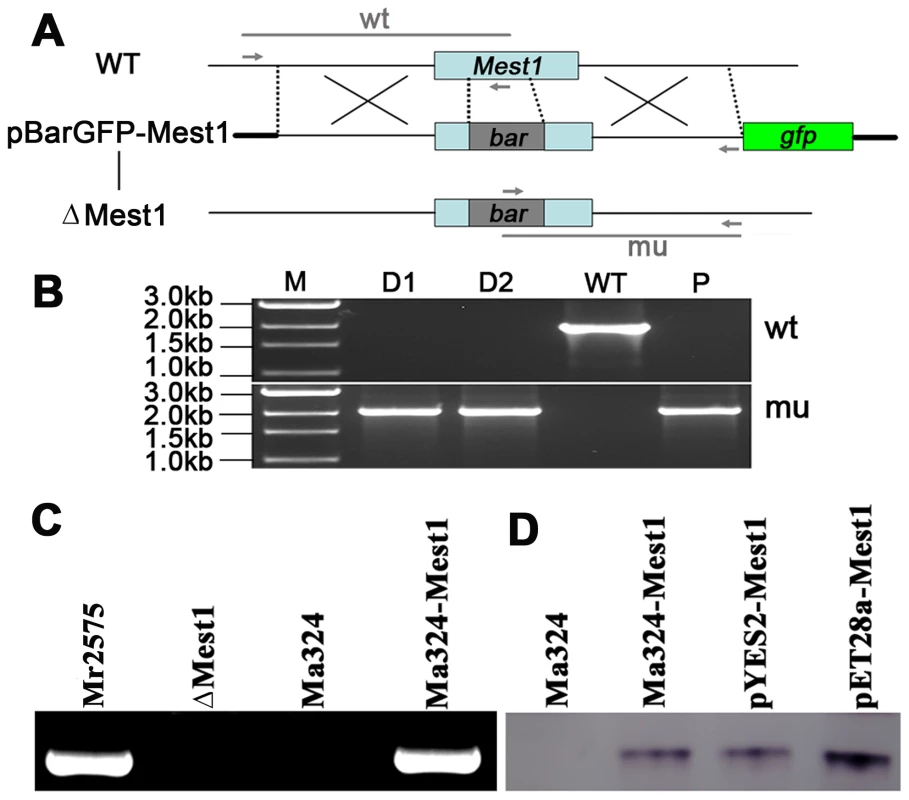

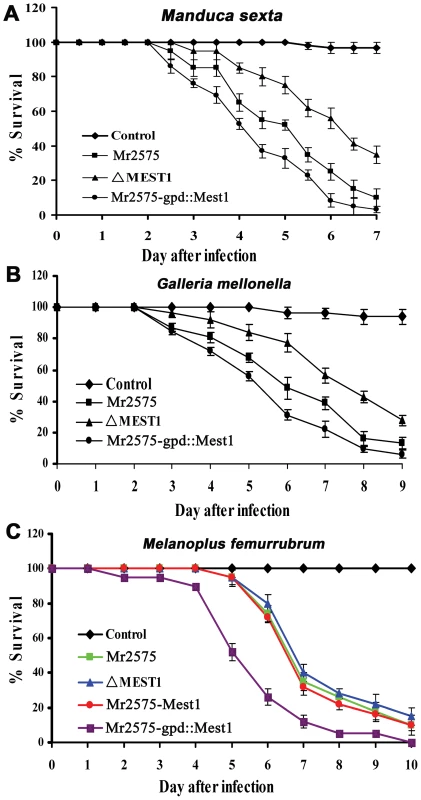

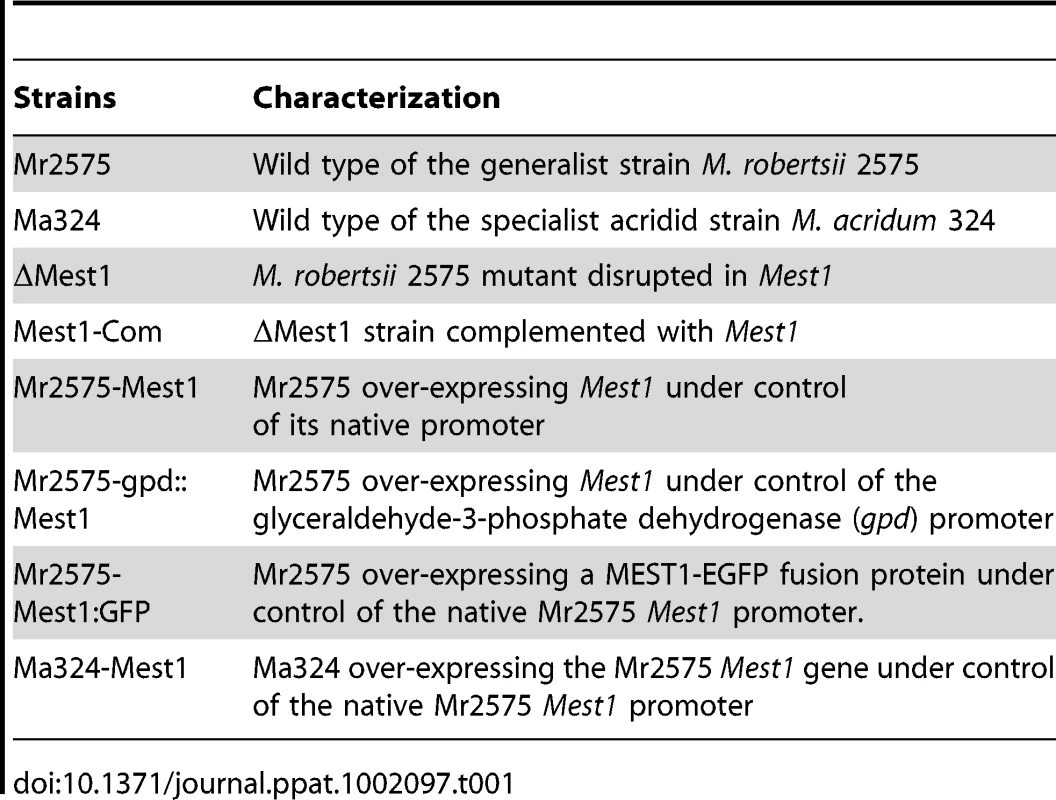

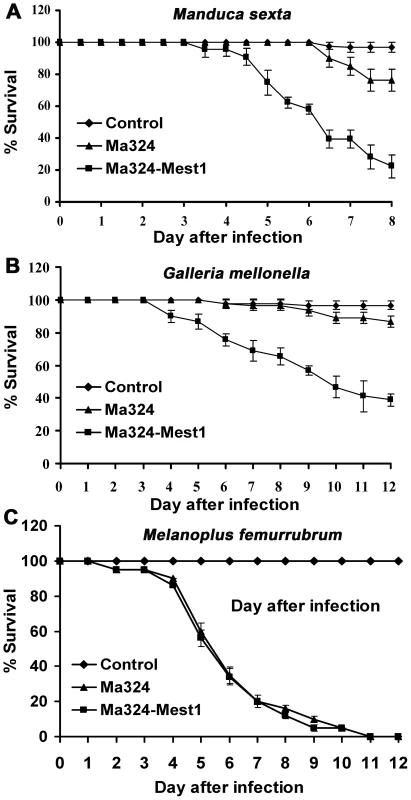

To study the function of Mest1, Mest1 null mutants (ΔMest1), were generated in Mr2575 by homologous replacement (Figure 2 and Table 1). Pathogenicity assays against Galleria mellonella and Manduca sexta caterpillars revealed a significant reduction in mortality and speed of kill by ΔMest1 relative to wild type M. robertsii Mr2575 (Figure 3A and 3B), while virulence against acridid grasshoppers (Melanoplus femurrubrum) was unaltered (Figure 3C). To demonstrate that the altered phenotype of ΔMest1 was specifically due to gene inactivation, the Mest1 gene was reintroduced into ΔMest1 in single copy. Six isolates of the resulting complemented strain (Mest1-Com) infected Galleria in an identical fashion as the wild type indicating successful complementation. Overexpression of Mest1 under control of the constitutive glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gpd) promoter (Mr2575-gpd::Mest1) resulted in a significant increase in virulence against both caterpillars (Manduca and Galleria) and grasshoppers (Figure 3C). Mr2575 transformed with an additional copy of Mest1 under control of its native promoter increased pathogenicity to lepidopterans but not grasshoppers, suggesting that Mest1 is not activated by the wild type fungus on grasshoppers.

Fig. 2. Disruption of the Mest1 gene in Metarhizium robertsii Mr2575.

(A) Schematic representation of the Mest1 wild type (WT) locus and the plasmid pBarGFP-Mest1 (containing two regions homologous to the Mest1 reading frame), that was used for gene disruption through double crossover recombination. Replacement- and WT-specific primer combinations and expected fragments are shown as grey lines. (B) Replacement-specific PCR analysis. Confirmation of the predicted gene targeting conducted with primer combinations that only amplify a signal in the recombinant locus (mu). The absence of a WT-specific signal in the clonal disruptants ΔMest1 (D1, D2) and plasmid pBarGFP-Mest1 (P) confirms the genetic homogeneity of the mutant isolates. (C) MEST1 expression in M. acridum Ma324 was verified by RT-PCR using cDNA from wild type Mr2575, Ma324, mutant (ΔMest1) and transgenic strain Ma324-Mest1. (D) MEST1 expression in M. acridum Ma324-Mest1, E. coli (pYES2-Mest1), and yeast cells (pET28a-Mest1) was confirmed by Western blot using a 6-Histidine Epitope Tag Antibody. Fig. 3. Pathogenicity of Metarhizium robertsii strains.

(A) Survival of Manduca sexta larvae following topical application with suspensions of 107 conidia/ml of Mr2575, mutant ΔMest1, or overexpression strain Mr2575-gpd::Mest1 under control of the constitutive gpd promoter. (B) Survival of Galleria mellonella larvae following topical application with suspensions of 107 conidia/ml of Mr2575, mutant ΔMest1, or Mr2575-gpd::Mest1. (C) Survival of grasshopper Melanoplus femurrubrum following application of 3 µl of 108 conidia/ml of Mr2575, mutant ΔMest1, Mr2575-Mest1 under native promoter control, or Mr2575-gpd::Mest1 per grasshopper pronotum. Control insects were treated with 0.01% Tween-80. Error bars indicate standard errors. Tab. 1. List of <i>Metarhizium</i> strains used in this study.

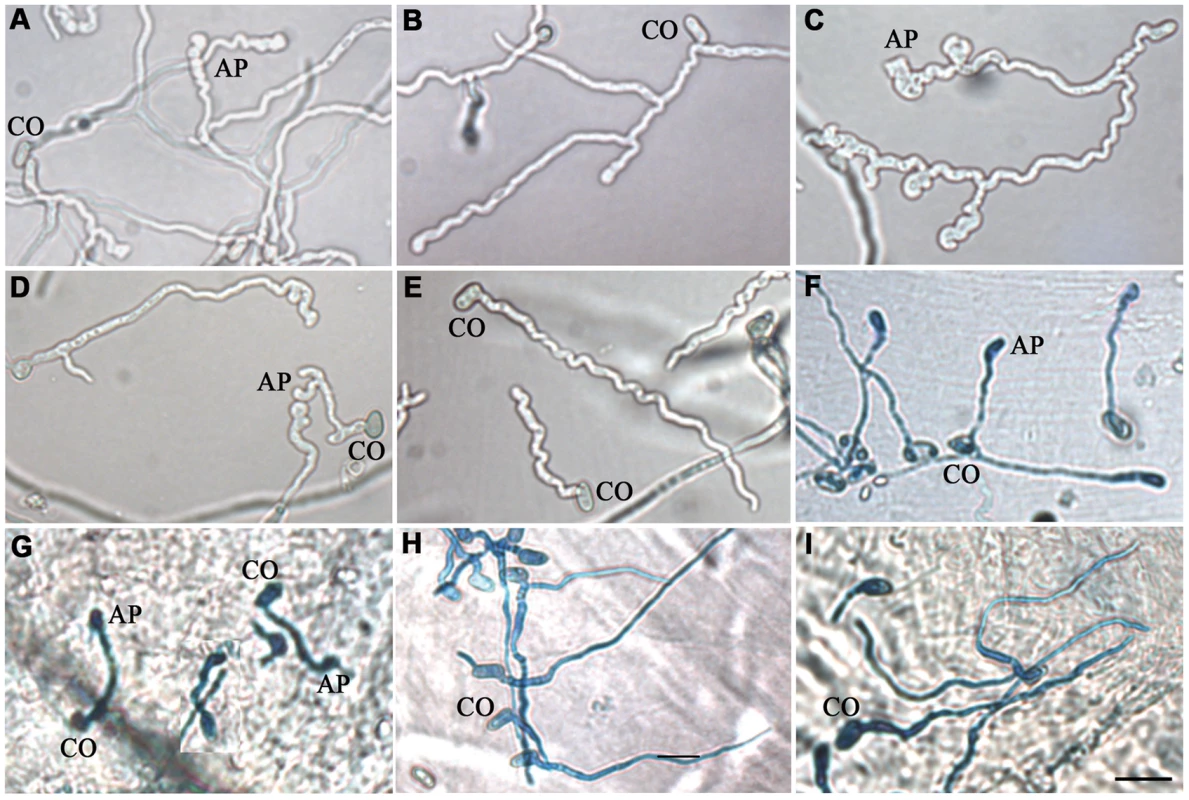

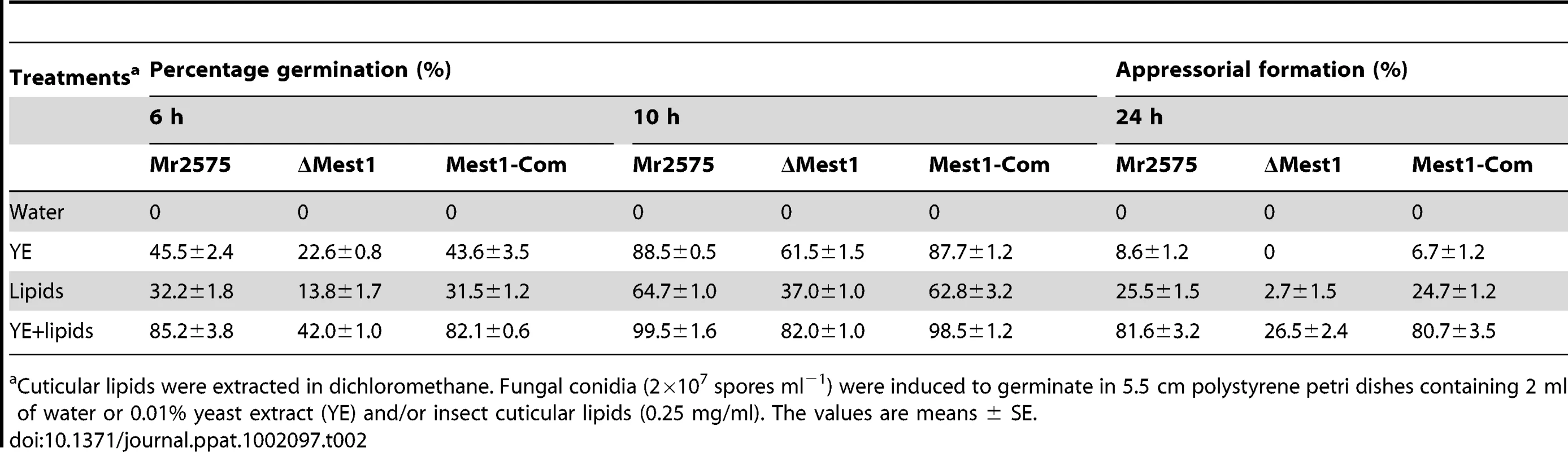

To elucidate whether Mest1 is needed for developmental processes, wild type Mr2575, ΔMest1 and Mest1-Com strains were grown on SDA (Sabouraud dextrose agar) or SDB (Sabouraud dextrose broth) (nutrient rich conditions), in 0.01% YE (Yeast extract) plus Manduca cuticular lipids (0.25 mg/ml) and on ground grasshopper or Manduca cuticles. There was no significant difference in sporulation, germination and growth rates between M. robertsii Mr2575, ΔMest1 and Mest1-Com on SDA or SDB, indicating that Mest1 does not facilitate these processes in nutrient rich conditions. Germination, germ tube formation and appressorial formation by Mr2575 on intact grasshopper and Manduca cuticles were similar (Figure 4). The germination rate of ΔMest1 was significantly (P<0.01) lower than that of wild type M. robertsii in 0.01% YE with or without Manduca cuticular lipids, and 24 h post-inoculation only 2.7±1.5 and 26.5±2.4% of ΔMest1 germlings had appressoria in YE and YE+lipids, respectively, as compared to 25.5±1.5 (YE) and 81.6±3.2% (YE+lipids) of wild type Mr2575 and 24.7±1.2% (YE) and 80.7±3.5% (YE+lipids) of complemented strain Mest1-Com (Table 2). Furthermore, ΔMest1 appressoria (3.6±0.1 µm×3.9±0.8 µm) were significantly smaller (P<0.01) than those of the wild type (4.1±0.2 µm×12.7±0.4 µm) on insect cuticles (Figure 4A and 4B). Conversely, overexpression of Mest1 in Mr2575-gpd::Mest1 resulted in multiple lobed appressoria on branched hyphae (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4. MEST1 regulates appressorial differentiation.

Growth of (A) wild type Metarhizium robertsii Mr2575, (B) mutant ΔMest1, (C) over-expressing strain Mr2575-gpd::Mest1, (D) transgenic strain Ma324-Mest1, and (E) wild type Metarhizium acridum Ma324 in YE+Manduca sexta cuticular lipids. Appressoria formed by transgenic strain Ma324-Mest1 on (F) Galleria mellonella and (G) M. sexta cuticles compared to differentiation of wild type Ma324 on (H) G. mellonella and (I) M. sexta cuticles 24 h post inoculation. CO, conidia; AP, appressorium. Bar, 10 µm. The fungal hyphae and infection structure were stained by Lactophenol Cotton Blue stain. Tab. 2. Effects of Manduca sexta cuticular lipids on conidial germination and appressorial differentiation of Metarhizium robertsii strains.

Cuticular lipids were extracted in dichloromethane. Fungal conidia (2×107 spores ml−1) were induced to germinate in 5.5 cm polystyrene petri dishes containing 2 ml of water or 0.01% yeast extract (YE) and/or insect cuticular lipids (0.25 mg/ml). The values are means ± SE. Heterologous expression of Metarhizium robertsii MEST1 enables M. acridum to infect caterpillars

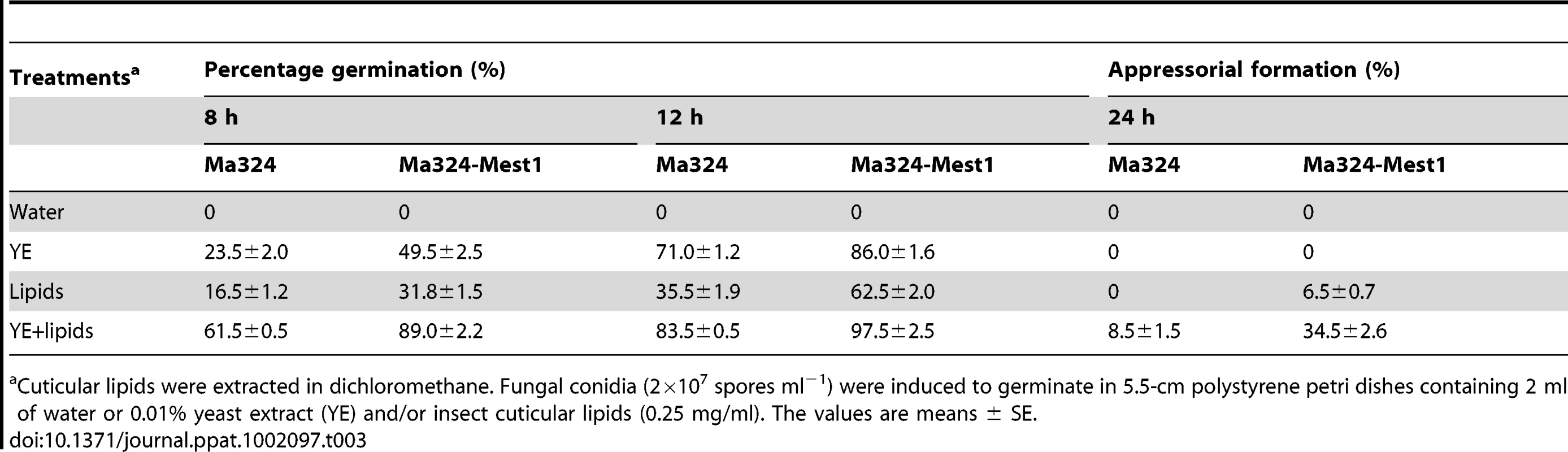

Wild type M. acridum Ma324 forms appressoria in locust cuticle lipid extracts and on locust wings [16]. We expressed a 2.7 kb clone encoding M. robertsii Mest1 under native control in Ma324 and studied its impact on pathogenicity and growth on caterpillar cuticle lipid extracts. Compared to the wild type Ma324, Ma324-Mest1 conidia exhibited significantly faster germination in Manduca cuticle lipids with or without YE (P<0.01). Approximately 7% of Ma324-Mest1 germlings produced appressoria in Manduca lipids compared to 35% of germlings in lipids+YE (Table 3). In contrast, wild type Ma324 did not form appressoria in either YE or Manduca lipid extracts, and <10% of germlings formed appressoria in Manduca lipid extracts+YE (Table 3). These appressoria were atypically small (2.8±0.2 µm×3.6±0.7 µm), whereas Ma324-Mest1 formed compound appressoria (3.9±0.3 µm×10.2±0.6 µm) at the end of germ tubes similar to those produced by Mr2575 (Figure 4D). Neither wild type Ma324 nor Ma324-Mest1 formed appressoria in water or YE, even though there was hyphal growth in the latter (Table 3). Thus heterologous expression of Mest1 by M. acridum is not sufficient by itself to trigger differentiation of appressoria.

Tab. 3. Effects of Manduca sexta cuticular lipids on conidial germination and appressorial differentiation of Metarhizium acridum strains.

Cuticular lipids were extracted in dichloromethane. Fungal conidia (2×107 spores ml−1) were induced to germinate in 5.5-cm polystyrene petri dishes containing 2 ml of water or 0.01% yeast extract (YE) and/or insect cuticular lipids (0.25 mg/ml). The values are means ± SE. Unlike wild type Ma324, Ma324-Mest1 produced appressoria within 24 hours of inoculation onto G. mellonella and M. sexta cuticles (Figure 4F and 4G). Pathogenicity assays showed that Ma324-Mest1 kills M. sexta and G. mellonella larvae, even though these are very poor hosts for the wild type at the spore dose tested (Figure 5A and 5B). The LT50 (time required to kill 50%) values of M. robertsii Mr2575 and Ma324-Mest1 against M. sexta were similar, being 5.1 days and 6.2 days, respectively. Inoculation of caterpillars with Ma324-Mest1 caused localized melanization (indicating cuticle penetration) and sluggishness similar to Mr2575, whereas caterpillars developed no symptoms with the wild type Ma324 8 days post-inoculation. Ma324-Mest1 was able to complete the full pathogenic life cycle on caterpillars as cadavers quickly became covered in spores. In contrast, wild type Ma324 only produced spores on the cadavers of a preferred acridid host M. rubrum (Figure S1). The LT50 values of Ma324 (4.9±0.2 d) and Ma324-Mest1 (4.7±0.6 d) against M. rubrum were not significantly different (Figure 5C), suggesting that the unknown esterases/lipases used by Ma324 for mobilizing internal nutrients are as efficient as MEST1, but only expressed on its specific hosts.

Fig. 5. Pathogenicity of Metarhizium acridum strains.

(A) Survival of Manduca sexta or (B) Galleria mellonella larvae following topical application with suspensions of 107 Ma324 or Ma324-Mest1 conidia/ml. (C) Survival of Melanoplus femurrubrum following application of 3 µl of 108 conidia/ml of Ma324 or Ma324-Mest1 per grasshopper pronotum. Control insects were treated with 0.01% Tween-80. Error bars indicate standard errors. Mr2575 expresses MEST1 during nutrient deprivation

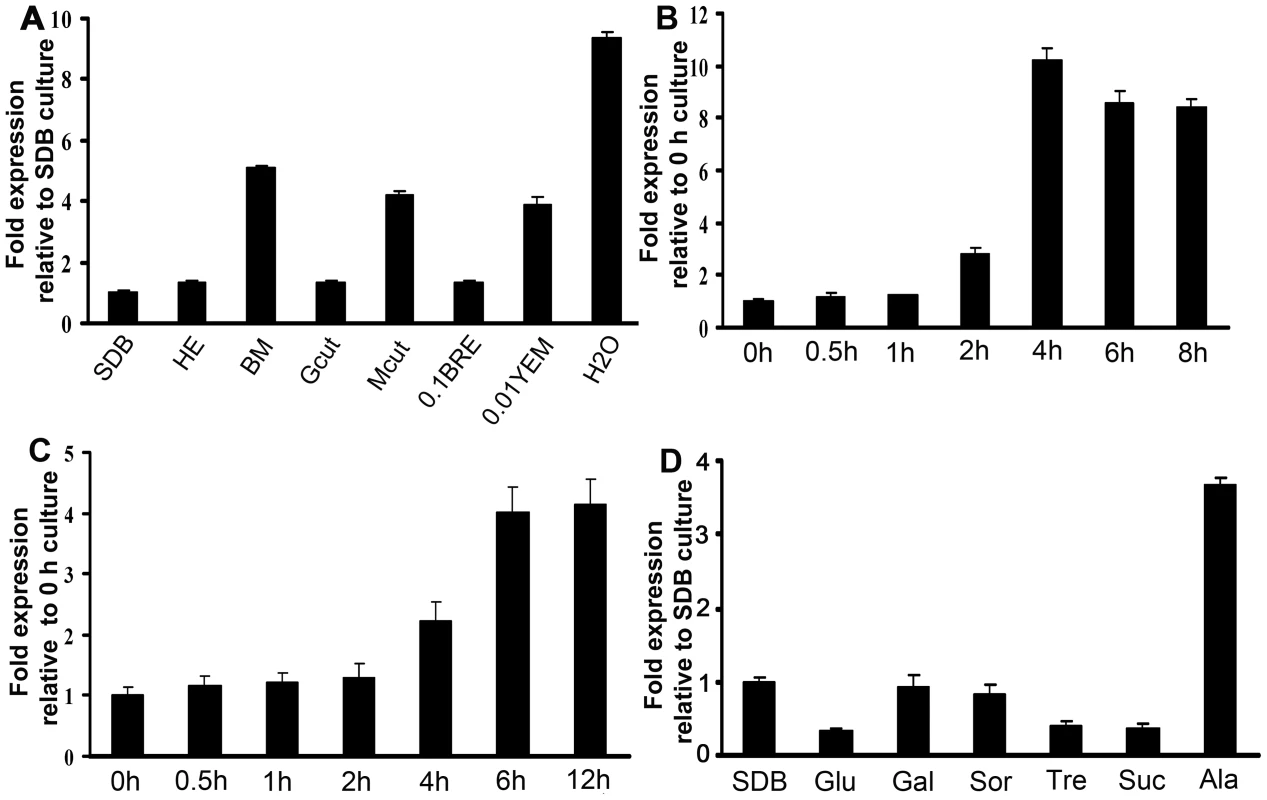

Transcript levels of Mest1 gene and two reference genes gpd (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and tef (translation elongation factor 1-α) were measured using SYBR dye technology (Applied Biosystems, CA) and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. Real-time PCR analysis demonstrated stronger expression of Mest1 by wild type Mr2575 in nutrient-poor media including water, basal medium and 1% Manduca cuticle relative to nutrient-rich media such as insect hemolymph or SDB (Figure 6A). We also analyzed Mest1 expression in time course studies. Mest1 was activated within 2 h of conidia being incubated in H2O but activation took up to 4 h when cultured in 1% ground Manduca cuticle medium (Figure 6B and 6C).

Fig. 6. Mest1 expression in wild type Mr2575, as measured by quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

(A) Analysis of Mest1 expression by wild type Mr2575 grown for 6 h in Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB), cell-free hemolymph (HE), basal medium, 1% grasshopper cuticle (Gcut), 1% Manduca sexta cuticle (Mcut), 0.1% bean root exudates (BRE), 0.01% yeast extract medium (YEM) and water. Quantitative RT-PCR time course analyses of Mest1 expression by wild type M. robertsii Mr2575 incubated in (B) water for up to 8 h, or (C) 1% (w/v) ground M. sexta cuticle for up to 12 h. (D) Effect of sugars on Mest1 expression by Mr2575. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Mest1 expression by wild type Mr2575 grown in SDB or basal medium (BM) complemented with 1% glucose (Glu), 1% galactose (Gal), 1% sorbose (Sor), 1% trehalose (Tre), 1% sucrose (Suc) or 1% alanine (Ala). Culture conditions and RNA extraction were as described previously [38]. gfp and tef were used as reference genes. Catabolite repression is a common mechanism by which easily available carbon sources decrease the expression of enzymes required for the use of other more complex nutrients such as lipids [23]–[25]. Real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that Mest1 expression was repressed in Mr2575 when grown on glucose, galactose, sorbose, fructose, trehalose or sucrose as sole carbon sources (Figure 6D). These results suggest that Mest1 expression occurs when Mr2575 needs to access nutrient reserves. However Mest1 expression was increased by 1% alanine, a common component of insect cuticles and not by locust cuticle, suggesting that the availability of easily accessible nutrients is not the only controlling factor for Mest1 expression.

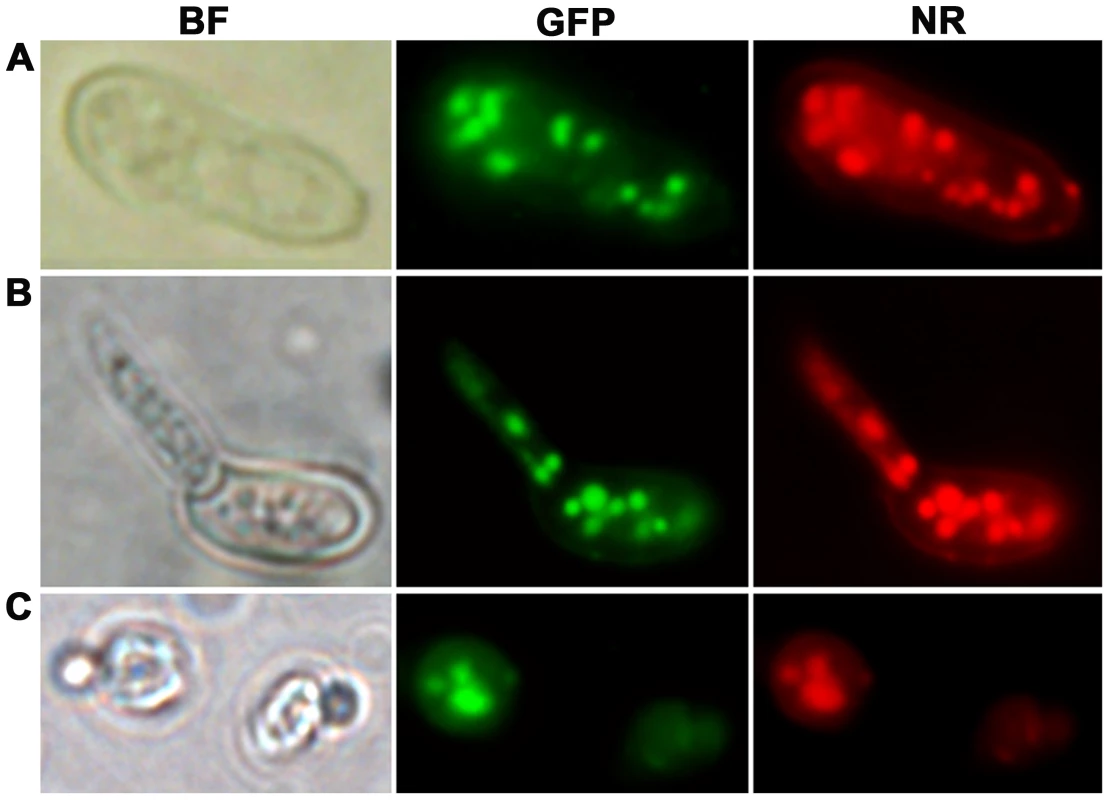

MEST1 localizes exclusively to lipid droplets

To visualize the intracellular targeting of MEST1 in vivo, MEST1 tagged at its C-terminus with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy of living Mr2575 cells. We also determined whether lipid droplet localization is a general quality of MEST1 by expressing it in the yeast S. cerevisiae, as these lack an endogenous MEST1-like protein. The GFP signal co-localized with lipid droplets stained with the neutral lipid stain Nile red in Mr2575 and the transformed yeast cells, confirming that MEST1 is binding to lipid droplets (Figure 7). No additional diffuse cytoplasmic signal was seen with either GFP or Nile Red.

Fig. 7. Intracellular localization of MEST1 in Metarhizium robertsii Mr2575 and budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Co-localization of MEST1 and neutral lipids demonstrated by Nile red staining of GFP-MEST1 expressing cells in (A) an ungerminated M. anisopliae conidium, (B) a germinated M. anisopliae conidium and (C) a budding yeast (S. cerevisiae) cell. BF, bright field microscopy. GFP, fluorescence filter. NR, Nile red staining. The expression patterns and the intracellular localization of MEST1 are therefore consistent with the protein playing a part in mobilizing global triacylglycerol storage by acting at the level of lipid droplets.

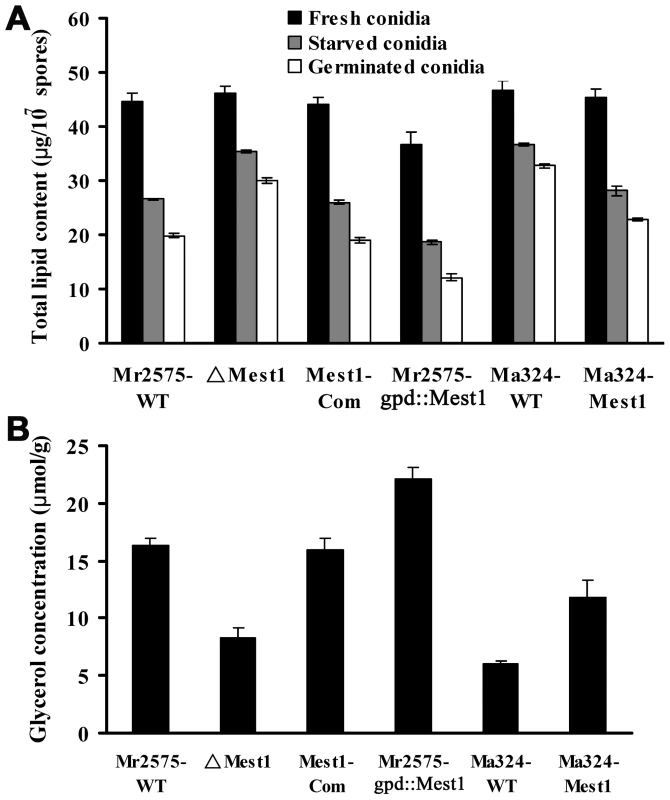

MEST1 plays an important role in lipid hydrolysis

In spite of possessing endogenous nutrient reserves, germination of M. robertsii requires external nutrients, albeit these can be at very low levels. When conidia are incubated in water they swell but do not germinate [13]. To test the involvement of MEST1 in lipid metabolism, we compared the lipid content of M robertsii Mr2575, ΔMest1, Mest1-Com, Mr2575-gpd::Mest1, M. acridum Ma324 and Ma324-Mest1. Except for the reduced lipid content of Mr2575-gpd::Mest1, which constitutively expresses Mest1, conidia from the tested strains showed no significant differences in their lipid content, indicating that MEST1 is not required for lipid storage (Figure 8A). As expected, total lipid content in all strains fell significantly (P<0.01) as nutrient reserves were mobilized during nutrient stress (conidia incubated in water) and during germination on 1% alanine. However, germlings of the wild type M. robertsii Mr2575 contained only 44.4% of the original lipid present in conidia as compared to 65.2% in the mutant ΔMest1. The complemented strain Mest1-Com had similar lipid content as wild type strain Mr2575. Ma324-Mest1 contained 50.3% of the original lipid as compared to 70% in wild type M. acridum Ma324, demonstrating that the transgenic Mest1 was hydrolyzing lipids in Ma324-Mest1 (Figure 8A).

Fig. 8. Determination of lipid content.

(A) Lipid content in conidia freshly harvested from PDA plates (black bars), nutrient-stressed conidia soaked in water for 36 h (grey bars) and conidia germinated in 1% alanine for 12 h (white bars). (B) Glycerol content in the six strains grown for 48 h in BM plus 0.25 mg/ml Manduca cuticle lipids. Triglycerides are degraded into fatty acids and glycerol. Consistent with more rapid hydrolysis of triglycerides, the glycerol content of M. robertsii Mr2575 was 1.98-fold higher (P<0.01) than in the disruptant ΔMest1-2575, while the over-expression strain Mr2575-gpd::Mest1 had 1.35-fold higher glycerol than the wild type strain Mr2575 (Figure 8B), suggesting that MEST1 contributes to the generation of turgor pressure in M. robertsii. The complemented strain had similar glycerol content as WT Mr2575. Similarly, heterologous expression of M. robertsii MEST1 in M. acridum Ma324 resulted in a 1.95-fold increase in glycerol content compared to wild type Ma324 (Figure 8B).

To determine if addition of exogenous nutrients overcomes the inability of wild type M. acridium to infect lepidopterans, we inoculated G. mellonella caterpillars with Ma324 spores suspended in 1% nutrient solutions (SDB, glucose, glycerol, or N-acetylglucosamine), or we topically applied pre-germinated conidia ± exogenous nutrients. Neither exogenous nutrients nor pregermination triggered differentiation of infection structures on insect cuticle, and consequently M. acridum was unable to infect caterpillars (Table S2).

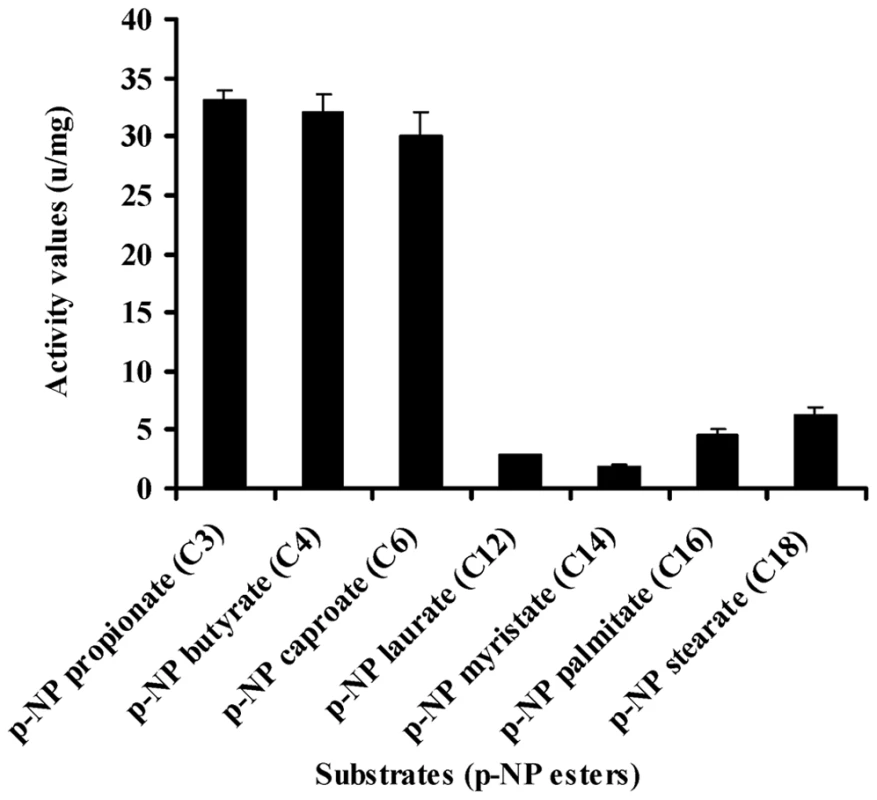

MEST1 hydrolyzes typical esterase substrates

To investigate the substrate specificity of MEST1, we expressed Mest1 in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells. SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis confirmed that a novel 47 kDa band in the transformed E. coli (ED3) cell lysates was MEST1-(His)6 fusion (Figure 2D and Figure S2). Attempts to purify six-His-tagged MEST1 expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells failed, which could be because the six-His tag is inaccessible in this protein. Therefore, esterase activity was measured in crude extracts, with similar extracts from E. coli Rosetta (DE3) transformed with the corresponding empty vector used as control. The substrate specificity of the expressed MEST1 was determined against p-nitrophenyl esters with different carbon chain-lengths (Figure 9). MEST1 exhibited a marked preference for short-chain fatty acids, with highest activity against p-NP propionate (C3), p-NP butyrate (C4) and p-NP caproate (C6). As is typical for esterases [26], the enzyme was much less active against p-NP esters with longer-chain lengths.

Fig. 9. Esterase activity of MEST1 is highest in the presence of short-chain esters (C4–C8).

Substrate specificity of MEST1 was determined by hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl esters with different carbon chain lengths. The activity values are reported as means ± standard errors from three independent assays using crude cell extracts of E. coli Rosetta (DE3) expressing MEST1 as compared to extracts from E. coli transformed with the corresponding empty vector. Discussion

The genus Metarhizium provides a novel model system to study evolutionary processes as it includes species such as M. robertsii with broad host ranges, as well as M. majus, M. flavoviride and M. acridum that are specific for scarabs, hemipterans and acridids, respectively [5]. M. acridum Ma324 in particular has been widely used for locust control. The genetic distinctness of M. acridum from generalist strains implies evolutionarily conserved host use patterns. However, being a generalist does not preclude M. robertsii strains from showing adaptations to nutrients on frequently encountered hosts. For example, nutrients on Hemiptera (e.g., aphids) are supplemented by insect secretions rich in sugars while beetles carry low levels of nitrogenous nutrients. Consistent with this, many hemipteran-derived lines produce appressoria in glucose medium whereas coleopteran-derived lines do not [27]. Closely related strains show these differences indicating that there are genetic mechanisms allowing rapid adaptation [28].

Lipids are the main nutrient reserve in fungal spores [16], [25]. In addition, lipid bodies are transported to the developing appressoria and degraded to release glycerol, which contributes to the hydrostatic pressure that provides a driving force for mechanical penetration [15]. This process is controlled by a perilipin that surrounds the lipid droplets and is predominantly expressed when M. robertsii is engaged in accumulating lipids in nutrient rich conditions. The perilipin layer is broken down during nutrient deprivation which presumably allows esterases/lipases to hydrolyze the lipid [15]. In this paper we show that unlike perilipin, Mest1 is predominantly expressed when lipids are being broken down. Disrupting Mest1 (ΔMest1) did not interfere with saprophytic growth of Mr2575 in nutrient rich conditions showing that its function is only important when it is adaptive for the fungus to mobilize endogenous nutrient reserves. Compared to ΔMest1, wild type Mr2575 grown in nutrient poor media or with cuticular lipids germinated faster and the germlings contained less lipid and more glycerol, while overexpression of Mest1 further boosted germination as well as appressorial differentiation. Intracellular lipid content was also significantly reduced and glycerol content increased in Ma324-Mest1 compared to wild type Ma324. These findings indicate that MEST1 is required by M. robertsii for rapid hydrolysis of endogenous energy reserves during germination and for infection structure formation. Lipid droplet enzymes have not been studied in filamentous fungi, but in yeasts all lipid droplet associated proteins are involved in the mobilization of triacylglycerols under conditions of fatty acid starvation [29]. The nutrient poor conditions that induce expression of Mest1 are a necessary trigger for virulence as M. robertsii strain Mr2575 only produces infection structures on cuticle surfaces with low levels of nutrients [13]. However, in ΔMest1 the mobilization of stored lipids was delayed, but not abolished, suggesting the existence of additional enzymes involved in breakdown of lipid droplets.

It seems clear from culturing the Ma324-Mest1 in yeast extract medium, that MEST1 expression is not sufficient by itself to induce appressoria production. Consequently, production of appressoria by Ma324-Mest1 on M. sexta and G. mellonella cuticles suggests that these have at least some of the inducers required by Ma324 for appressorial differentiation (Figure 2F and 2H). The incidence of infection and the severity of the disease symptoms shown by Ma324-Mest1 were similar to those observed with M. robertsii Mr2575, an authentic pathogen of caterpillars. We have therefore shown that inserting a single gene able to mobilize nutrient reserves from a broad spectrum pathogen into a specialist is enough to broaden the latter's host range. This implies that mobilization of nutrient reserves or lack thereof can account for the broad host range of M. robertsii and the restricted host range of M. acridum, respectively. Restricted host range could therefore be due essentially to biochemical limitations. Addition of exogenous nutrients (SDB, glucose, N-acetylglucosamine, glycerol) or pregermination on rich medium (SDB) did not overcome the inability of M. acridum to infect caterpillars. The implication is that intracellular lipid reserves are not only a nutrient source but also a source of chemical signals triggering infection processes. Consistent with this, disrupting the Mest1 gene in M. robertsii (ΔMest1) reduces virulence against caterpillars but not grasshoppers, indicating that the physiological conditions on grasshoppers and caterpillars are different, and there are different mechanisms for linking signals on the host surfaces with differentiation of infection structures. Hydrocarbons comprise over 90% of the wax layer on the surface of grasshoppers, with the balance being composed of wax esters, free fatty acids and triacylglycerides, whereas in larval Lepidoptera, aliphatic alcohols are the most abundant compounds, and triacylglycerides are absent [30]. M. acridum extensively hydrolyzes surface lipids and waxes during germination and pre-penetration growth on locust cuticles [31]. A possible explanation for the different responses to grasshopper and caterpillars may be that breakdown products of triglycerides on grasshoppers provide signaling molecules to trigger infection processes by Ma324, but on caterpillars MEST1 provides these signals from stored triglycerides.

As the transgenic M. acridum Ma324-Mest1 is able to kill caterpillars, wild type M. acridum must have retained most of the genetic machinery required for parasitism of insects outside its natural host range. This is consistent with the developmental processes within M. anisopliae and M. acridum being very similar, e.g. formation of germ tubes, appressoria, penetration pegs unicellular blastospores, and multi-cellular hyphal bodies that facilitate the infection of target insects, proliferation within haemolymph, and eventual eruption through the host cadaver. Besides novel lineage specific proteins such as MEST1, host recognition may therefore be determined by regulatory controls that allow expression of pathogenicity genes that are not expressed on non-hosts. Expression of Mest1 under its native M. robertsii promoter in M. acridum may have broadened host range by bypassing its need for esterases that are regulated by specific locust-related stimuli.

The impact of a single gene on host range suggests that host shifts may have occurred during Metarhizium speciation by the acquisition or loss of novel pathogenicity factors. The presence of a MEST1 ortholog in the related N. haematococca is consistent with M. acridum and M. robertsii having inherited MEST1 from a common ancestor. Their patchy distribution could be explained by rapid mutation or multiple lineage specific gene loss events in M. acridum and other fungi. An important question is whether utilizing MEST1-like esterases during infection processes is the ancestral state. There are 16 esterases in M. robertsii (6 of which are secreted) and 18 in M. acridum (6 secreted) [22], and Metarhizium spp. express multiple esterases on insect cuticles [32]. It seems likely that Ma324 uses the same esterases for mobilizing lipids as other fungi, and the Mest1 gene in M. robertsii has acquired unique functions in this species as it is clearly highly dispensable. The new functions could potentially have turned the recipient into a novel pathogen or allowed it to infect new hosts. Expression of Mest1 in Ma324 does not change virulence against its preferred grasshopper host suggesting that acridids do not represent a specialized ecological niche in which a M. robertsii-like MEST1 activity is detrimental, and there is no evidence in this study for any conditional benefits in losing MEST1's function. This is consistent with the infection-related functions of MEST1 arising de novo in M. robertsii.

This study has important safety implications for field applications of M. acridum as it shows that Ma324 lacks a gene important for opportunism and this should severely constrain the possibility of host switching to non-target beneficials. In addition, an understanding of how Mest1 affects fungal responses to hosts, and identification of the signaling cascades involved in regulating the mobilization of nutrient reserves will provide fundamental new insights into the initial steps that are required for the establishment of a compatible interaction between fungi and their hosts.

Materials and Methods

Strains and culture conditions

M. robertsii Mr2575 and M. acridum Ma324 are wild type strains that were obtained from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Entomopathogenic Fungus Collection (ARSEF) in Ithaca, N.Y. Strain Mr2575 can infect caterpillars (Manduca sexta), beetles (Cucurlio caryae) [33], grasshoppers (Melanoplus femurrubrum) and locusts (Schistocerca gregaria) [34]. M. acridum Ma324 ( = CSIRO FI 485) is the active ingredient of “Green Guard” used for locust control in Australia. In the field it is found exclusively in acridids, and is only infectious to caterpillars in laboratory conditions at very high spore concentrations. Fungal strains were maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) at 27°C. Conidia were obtained from 10 day old PDA cultures. For preparation of genomic DNA and RNA, fungal spores were cultured in Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB) (2×106 conidia/ml) at 27°C.

Mest1 gene cloning, disruption, complementation and over-expression

Mest1 was originally identified as an EST expressed when strain Mr2575 was grown on insect cuticle [17]. The full-length sequence of the Mest1 cDNA was obtained from the EST using RACE, and a genomic clone was obtained using the DNA Walking Speed Up Kit II (Seegene Inc., Rockville, Maryland, USA). The primers are listed in Supplementary Information, Table S1.

For targeted deletion of Mest1, the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the Mest1 ORF were amplified by PCR from Mr2575 genomic DNA, and then subcloned into the XbaI and SpeI sites of the binary vector pBarGFP [35]. The gene disruption construct (pBarGFP-Mest1) was then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens AGL-1 for targeted gene disruption by homologous recombination as described previously [36]. Replacement-specific PCR amplifications of the Mest1 locus were performed with specific primer pairs (primers are listed in Table S1) that amplify either the wild type or the mutant gene locus.

To revert disruptant ΔMest1, the full-length Mest1 gene with its native promoter and terminator sequences was amplified by PCR and cloned into the XbaI site of pBenGFP [36] to generate complementation vector pBenGFP-Mest1. The complementary strain Mest1-Com was generated by reintroduction of pBenGFP-Mest1 into the disruptant ΔMest1 using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. M. robertsii MEST1 was heterologously expressed in specialist M. acridum Ma324 using vector pBenGFP-Mest1 to generate Ma324-Mest1. Four putative transformants were chosen and verified for Mest1 gene expression by RT-PCR (data now shown).

A transformation vector was constructed by amplifying the coding region of Mest1 from the cDNA clone with primer pairs Mest1F and Mest1R (Table S1) containing a 5′ BamHI site and a 3′ EcoRI site plus a 6×His-tag. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T/A cloning vector (Promega), and the sequence of the Mest1 amplicon was confirmed by sequencing. The Mest1 gene fragment was released with BamH I and SmaI, and subcloned into pBarGPE1 [37] downstream of a constitutive Aspergillus nidulans gpdA promoter to obtain pBarGPE1-Mest1. The Mest1 cassette was released by cleavage with BglII, and then inserted into the BglII site of pBarGFP to generate pBarGFP-gpdA::Mest1 for A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation into Mr2575. The resulting strain was designated as Mr2575-gpd::Mest1. Genomic DNA was extracted from putative transformants for Southern blot analysis as previously described [18]. Mest1 gene expression in transformants was verified by RT-PCR [38].

GFP fusion construct and subcellular localization of MEST1

To determine the subcellular localization of MEST1, the promoter region (∼1.5 kb) together with the Mest1 ORF minus the 3′ TAA stop codon was amplified with primer pairs Mest1F2 and Mest1R2 (Table S1) and inserted into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBarGPE1 [37] to generate pBarGPE1-Pmest1::Mest1. An enhanced Green Fluorescent gene (eGFP) was amplified from pEGFP (Clontech) with primers gfpF1 and gfpR1 containing a 5′ EcoRI site and a 3′ XhoI site, and integrated into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of the plasmid pBarGPE1-Pmest1::Mest1 to generate pBarGPE1-Pmest1::Mest1:GFP. The construct was restricted with Pml1 and BamHI, and the released cassette Pmest1::Mest1:GFP was subcloned into the BamHI and EcoRV sites of the binary vector pPK2 [39] to generate pBar-Pmest1::Mest1:GFP. The final construct was transformed into wild type Mr2575 using A. tumefaciens AGL-1 to generate Mr2575-Mest1:GFP.

We also determined whether MEST1 localizes to lipid droplets in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a fungus unrelated to Metarhizium and lacking an endogenous MEST1 protein. The Mest1 ORF was amplified with primers Mest1yesF and Mest1yesR (Table S1) and the product integrated into the EcoRI and NotI sites of pYES2 (Invitrogen). The resulting pYES2-Mest1 or the parent plasmid pYES2 (used as a control) were transformed into S. cerevisiae strain INVSc1 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Nile red, (9-diethylamino-5H-benzo [alpha] phenoxazine-5-one) was used to stain intracellular lipid droplets, which were viewed by fluorescence microscopy as previously described [15].

Reverse transcription and real-time RT-PCR

To monitor Mest1 expression in different growth conditions, fungal spores were incubated (6 hrs) in 10 ml of fresh SDB, Manduca sexta hemolymph [17], basal medium [BM, 0.02% KH2PO4, 0.01% MgSO4 (pH 6)], water or water supplemented with either 0.1% bean root exudate [40]) or 1% insect cuticle as described [38]. Fungal cells were also incubated in BM supplemented with 1% glucose, 1% galactose, 1% sorbose, 1% trehalose, 1% sucrose or 1% alanine. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). First strand cDNA was synthesized using Verso cDNA Kit (ABgene) according to manufacturer's instructions. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) reactions were performed using a Quantitative real-time SYBR Green MasterMix Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time instrument and ABI Prism SDS 1.2.2. software. The qPCRs were performed using the following conditions: 50°C for 2 min, then denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 min. The primers used for gene Mest1 and the reference genes gpd and tef are listed in Table S1.

Lipid extraction and quantification

To test the involvement of MEST1 in lipid metabolism, the cell lipid content was quantified by the sulfo-phospho-vanillin method as previously described [15]. A reference standard curve was generated using triolein (Sigma). To determine whether starvation stress induces the hydrolysis of residual stored lipids, conidia from wild type M. robertsii Mr2575, mutant ΔMest1, complementary strain Mest1-Com, over-expression strain Mr2575-gpd::Mest1, wild type M. acridum Ma324 and transgenic Ma324-Mest1were incubated in H2O for 36 h, which causes spores to swell but not germinate, or induced to germinate in basal medium plus 1% alanine (wt/vol) for up to 12 h. The total lipid content of the conidia was assayed as described above.

Intracellular glycerol measurements

Fungal conidia were inoculated into BM supplemented with 0.25 mg/ml of Manduca cuticle lipids [15] for up to 48 h. Cultures were harvested by filtration through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and 0.2 µm Millipore filter units, washed quickly with ice-cold BM, and resuspended in 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. The samples were heated to 95°C for 10 min and cell debris pelleted by centrifugation as described [41]. The glycerol concentration was assayed enzymatically using a glycerol determination kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). The data represent the average of three independent experiments.

Conidial germination and appressorium differentiation

The germination rate of conidia was measured by inoculating 20 µl of spore suspension (2×107 spores ml−1) in 5.5 cm polystyrene Petri dishes containing either 2 ml of water, 0.01% yeast exact (YE) and/or insect cuticle lipids (0.25 mg/ml). Three hundred spores from each of three replicates were recorded microscopically to assess germination and appressorial differentiation against the hydrophobic surface of the Petri dish. Appressoria were also induced against locust (Schistocerca gregaria) hind wings, Galleria mellonella and Manduca sexta cuticle as described previously [16].

Prokaryotic expression and Western blotting of MEST1

For prokaryotic expression of MEST1, the full length cDNA of Mest1 was cloned by RT-PCR using specific primers Mest1EexF and Mest1EexR (Table S1), restricted with EcoRI and NotI, and subcloned into the prokaryotic expression vector pET28a at the EcoRI and NotI sites to form pET28a-Mest1. E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells (Novagen) were transformed with the recombinant expression vector. His–tagged MEST1 production was induced by 0.2 mM IPTG in LB medium for 16 h at 28°C, and cells were lysed with the B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufactor's instructions. The His-tagged MEST1 was detected by Western blot analysis using rabbit Anti 6-Histidine Epitope Tag monoclonal antibody and anti-rabbit IgG (Fc), conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Invitrogen).

Esterase activity assay

Ester hydrolase activities were determined in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) transformed with pET28a-Mest1 or the empty vector pET28a. Cell extract (0.1 ml) containing ∼50 µg of protein and 0.1 ml of a p-NP-derivative substrate in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8) was incubated at 37°C. Enzyme activity was spectrophotometrically determined by measuring the liberation of p-nitrophenol as previously described [42]. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 µmol of p-NP per min per mg of protein under the assay conditions. Substrate specificity towards various p-nitrophenyl esters (Sigma-Aldrich) was determined using p-NP propionate (C3), p-NP butyrate (C4), p-NP caproate (C6), p-NP laurate (C12), p-NP myristate (C14), p-NP palmitate (C16), and p-NP stearate (C18) as substrates.

Virulence bioassay

The virulence of the wild type M. robertsii Mr2575, mutant ΔMest1, complementary strain Mest1-Com, over-expression strain Mr2575-gpd::Mest1, wild type M. acridum Ma324 and transgenic strain Ma324-Mest1 were assayed against wild caught 5th instar Melanoplus femurrubrum grasshoppers (College Park, Maryland) and newly molted fifth-instar larvae of Manduca sexta and Galleria mellonella (Carolina Biological supplies). An aliquot of 3 µl of fungal spore suspension was applied to the pronotum of each grasshopper as previously described [43]). Grasshoppers were then placed in clear plastic boxes at 28°C under an 18∶6-h photoperiod in humid conditions (>80%), and supplied daily with fresh wheat seedlings. Each box contained 10 grasshoppers; three containers were used for each dosage of fungus tested (3×105 or 5×105 spores/insect). Manduca sexta and Galleria mellonella were inoculated by topical immersion in conidial suspensions (1×107 conidia/ml) as previously described [38]. Mortality was recorded every 12 h. After death, cadavers were surface sterilized [35], and incubated in Petri dishes with a sterile wet cotton ball to promote fungal emergence, and thus confirm cause of death. Each treatment was replicated three times with 30 insects per replicate, and the bioassays were repeated twice. LT50 values were calculated with the SPSS program [44].

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

Sequence data reported here have been deposited in the GenBank database under the following accession numbers: Metarhizium robertsii Mest1 mRNA (HM747114), Mest1 genomic DNA (HM747115).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. WaltonJD 2006 HC-toxin. Phytochemistry 67 1406 1413

2. WolpertTJDunkleLDCiuffettiLM 2002 Host-selective toxins and avirulence determinants: What's in a name? Annu Rev Phytopathol 40 251 285

3. van der DoesHCRepM 2007 Virulence genes and the evolution of host specificity in plant-pathogenic fungi. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20 1175 1182

4. MylonakisECasadevallAAusubelFM 2007 Exploiting amoeboid and non-vertebrate animal model systems to study the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. PLoS Pathog 3 e101

5. BischoffJFRehnerSAHumberRA 2009 A multilocus phylogeny of the Metarhizium anisopliae lineage. Mycologia 101 512 530

6. BlanfordSChanBHJenkinsNSimDTurnerRJ 2005 Fungal pathogen reduces potential for malaria transmission. Science 308 1638 1641

7. de FariaMRWraightSP 2007 Mycoinsecticides and Mycoacaricides: A comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol Control 43 237 256

8. KanzokSMJacobs-LorenaM 2006 Entomopathogenic fungi as biological insecticides to control malaria. Trends Parasitol 22 49 51

9. GottarMGobertVMatskevichAAReichhartJMWangC 2006 Dual detection of fungal infections in Drosophila via recognition of glucans and sensing of virulence factors. Cell 127 1425 1437

10. DriverFMilnerRJTruemanJWH 2000 A taxonomic revision of Metarhizium based on a phylogenetic analysis of rDNA sequence data. Mycol Res 104 134 150

11. PengGXWangZKYinYPZengDYXiaYX 2008 Field trials of Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) against oriental migratory locusts, Locusta migratoria manilensis (Meyen) in Northern China. Crop Prot 27 1244 1250

12. ThomasMBReadAF 2007 Can fungal biopesticides control malaria? Nat Rev Microbiol 5 377 383

13. St LegerRJButtTMGoettelMSStaplesRSRobertsDW 1989 Production in vitro of appressoria by the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Exp Mycol 13 274 288

14. St LegerRJJoshiLBidochkaMJRizzoNWRobertsDW 1996 Characterization and ultrastructural localization of chitinases from Metarhizium anisopliae, M. flavoviride, and Beauveria bassiana during fungal invasion of host (Manduca sexta) cuticle. Appl Environ Microbiol 62 907 912

15. WangCSt LegerRJ 2007 The Metarhizium anisopliae perilipin homolog MPL1 regulates lipid metabolism, appressorial turgor pressure, and virulence. J Biol Chem 282 21110 21115

16. WangCSt LegerRJ 2005 Developmental and transcriptional responses to host and nonhost cuticles by the specific locust pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum. Eukaryot Cell 4 937 947

17. FreimoserFMScreenSBaggaSHuGSt LegerRJ 2003 Expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis of two subspecies of Metarhizium anisopliae reveals a plethora of secreted proteins with potential activity in insect hosts. Microbiology 149 239 247

18. WangSLeclerqueAPava-RipollMFangWSt LegerRJ 2009 Comparative genomics using microarrays reveals divergence and loss of virulence-associated genes in host-specific strains of the insect pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae. Eukaryot Cell 8 888 898

19. BergerRHoffmannMKellerU 1998 Molecular analysis of a gene encoding a cell-bound esterase from Streptomyces chrysomallus. J Bacteriol 180 6396 6399

20. BornscheuerUT 2002 Microbial carboxyl esterases: classification, properties and application in biocatalysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 26 73 81

21. KugimiyaWOtaniYHashimotoYTakagiY 1986 Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the lipase gene from Pseudomonas fragi. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 141 185 190

22. GaoQJinKYingSHZhangYXiaoG 2011 Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics of the model entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and M. acridum. PLoS Genet 7 e1001264

23. EbboleDJ 1998 Carbon catabolite repression of gene expression and conidiation in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol 25 15 21

24. GancedoJM 1998 Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62 334 361

25. RequenaNFullerPFrankenP 1999 Molecular characterization of GmFOX2, an evolutionarily highly conserved gene from the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae, down-regulated during interaction with rhizobacteria. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 12 934 942

26. VergerR 1997 Interfacial activation of lipases: Facts and artifacts. Trends Biotechnol 15 32 38

27. St LegerRJMayBAlleeLLFrankDCStaplesRC 1992 Genetic differences in allozymes and information of infection structures among isolates of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J Invertebr Pathol 60 89 101

28. St LegerRJBidochkaMJRobertsDW 1994 Germination triggers of Metarhizium anisopliae conidia are related to host species. Microbiology 140 1651 1660

29. JandrositzaAPetschniggaJZimmermannaRNatteraKScholzebH 2005 The lipid droplet enzyme Tgl1p hydrolyzes both steryl esters and triglycerides in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1735 50 58

30. ChapmanRF 1998 The Insects: structure and function New York Cambridge University Press 788

31. JarroldSLMooreDPotterUCharnleyAK 2007 The contribution of surface waxes to pre-penetration growth of an entomopathogenic fungus on host cuticle. Mycol Res 111 240 249

32. St LegerRJGoettelMRobertsDWStaplesRC 1991 Pre-penetration events during infection of host cuticle by Metarhizium anisopliae. J Invertebr Pathol 58 168 179

33. MoonYSDonzelliBGKrasnoffSBMcLaneHGriggsMH 2008 Agrobacterium-mediated disruption of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene in the invertebrate pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae reveals a peptide spore factor. Appl Environ Microbiol 74 4366 4380

34. DillonRJCharnleyAK 1991 The fate of fungal spores in the insect gut. ColeGTHochHC The fungal spore and disease initiation in plants and animals New York Plenum Press 129 156

35. FangWPava-RipollMWangSSt LegerR 2009 Protein kinase A regulates production of virulence determinants by the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae. Fungal Genet Biol 46 277 285

36. FangWPeiYBidochkaMJ 2006 Transformation of Metarhizium anisopliae mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Can J Microbiol 52 623 626

37. McCluskeyK 2003 The Fungal Genetics Stock center: from molds to molecules. Adv Appl Microbiol 52 245 262

38. WangCSt LegerRJ 2006 A collagenous protective coat enables Metarhizium anisopliae to evade insect immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 6647 6652

39. CovertSFKapoorPLeeMBrileyANairnCJ 2001 Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transformation of Fusarium circinatum. Mycol Res 105 259 264

40. WelteMACermelliSGrinerJVieraAGuoY 2005 Regulation of lipid-droplet transport by the perilipin homolog LSD2. Curr Biol 15 1266 1275

41. PhilipsJHerskowitzI 1997 Osmotic balance regulates cell fusion during mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 138 961 974

42. PrimNBlancoAMartinezJPastorFIJDiazP 2000 EstA, a gene coding for a cell-bound esterase from Paenibacillus sp. BP-23, is a new member of the bacterial subclass of type B carboxylesterases. Res Microbiol 151 303 312

43. NowierskiRMZengZJaronskiSDelgadoFSwearingenW 1996 Analysis and modeling of time-dose-mortality of Melanoplus sanguinipes, Locusta migratoria migratorioides, and Schistocerca gregaria (Orthoptera: Acrididae) from Beauveria, Metarhizium, and Paecilomyces isolates from Madagascar. J Invertebr Pathol 67 236 252

44. SPSS Inc 2001 SPSS for Windows, Rel. 11.0.1 Chicago SPSS Inc

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Glycosaminoglycan Binding Facilitates Entry of a Bacterial Pathogen into Central Nervous SystemsČlánek The SV40 Late Protein VP4 Is a Viroporin that Forms Pores to Disrupt Membranes for Viral ReleaseČlánek Pathogen Recognition Receptor Signaling Accelerates Phosphorylation-Dependent Degradation of IFNAR1

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 6- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The N-Terminus of the RNA Polymerase from Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis Virus Is the Determinant of Genome Attachment

- Evolutionary Analysis of Inter-Farm Transmission Dynamics in a Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Epidemic

- Glycosaminoglycan Binding Facilitates Entry of a Bacterial Pathogen into Central Nervous Systems

- Endemic Dengue Associated with the Co-Circulation of Multiple Viral Lineages and Localized Density-Dependent Transmission

- The SV40 Late Protein VP4 Is a Viroporin that Forms Pores to Disrupt Membranes for Viral Release

- The -glycan Glycoprotein Deglycosylation Complex (Gpd) from Deglycosylates Human IgG

- The Lipid Transfer Protein CERT Interacts with the Inclusion Protein IncD and Participates to ER- Inclusion Membrane Contact Sites

- Induction of Noxa-Mediated Apoptosis by Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Depends on Viral Recognition by Cytosolic Helicases, Leading to IRF-3/IFN-β-Dependent Induction of Pro-Apoptotic Noxa

- Environmental Constraints Guide Migration of Malaria Parasites during Transmission

- HIV-1 Efficient Entry in Inner Foreskin Is Mediated by Elevated CCL5/RANTES that Recruits T Cells and Fuels Conjugate Formation with Langerhans Cells

- Kupffer Cells Hasten Resolution of Liver Immunopathology in Mouse Models of Viral Hepatitis

- Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus H5N1 Infects Alveolar Macrophages without Virus Production or Excessive TNF-Alpha Induction

- Uses Host Triacylglycerol to Accumulate Lipid Droplets and Acquires a Dormancy-Like Phenotype in Lipid-Loaded Macrophages

- Compensatory T Cell Responses in IRG-Deficient Mice Prevent Sustained Infections

- Detection of Inferred CCR5- and CXCR4-Using HIV-1 Variants and Evolutionary Intermediates Using Ultra-Deep Pyrosequencing

- A Dynamic Landscape for Antibody Binding Modulates Antibody-Mediated Neutralization of West Nile Virus

- HSV-2 Infection of Dendritic Cells Amplifies a Highly Susceptible HIV-1 Cell Target

- “Rational Vaccine Design” for HIV Should Take into Account the Adaptive Potential of Polyreactive Antibodies

- Impact of Endofungal Bacteria on Infection Biology, Food Safety, and Drug Development

- Infection Reduces B Lymphopoiesis in Bone Marrow and Truncates Compensatory Splenic Lymphopoiesis through Transitional B-Cell Apoptosis

- The Intrinsic Antiviral Defense to Incoming HSV-1 Genomes Includes Specific DNA Repair Proteins and Is Counteracted by the Viral Protein ICP0

- Molecular Interactions that Enable Movement of the Lyme Disease Agent from the Tick Gut into the Hemolymph

- Pathogen Recognition Receptor Signaling Accelerates Phosphorylation-Dependent Degradation of IFNAR1

- A Freeze Frame View of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Transcription Defines a Minimal Length of RNA for 5′ Processing

- High Affinity Nanobodies against the VSG Are Potent Trypanolytic Agents that Block Endocytosis

- Tipping the Balance: Secreted Oxalic Acid Suppresses Host Defenses by Manipulating the Host Redox Environment

- Bacteria-Induced Dscam Isoforms of the Crustacean,

- Structural and Mechanistic Studies of Measles Virus Illuminate Paramyxovirus Entry

- Insertion of an Esterase Gene into a Specific Locust Pathogen () Enables It to Infect Caterpillars

- A Role for TLR4 in Infection and the Recognition of Surface Layer Proteins

- The Binding of Triclosan to SmeT, the Repressor of the Multidrug Efflux Pump SmeDEF, Induces Antibiotic Resistance in

- Low CCR7-Mediated Migration of Human Monocyte Derived Dendritic Cells in Response to Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Human Metapneumovirus

- HIV/SIV Infection Primes Monocytes and Dendritic Cells for Apoptosis

- Sporangiospore Size Dimorphism Is Linked to Virulence of

- Productive Parvovirus B19 Infection of Primary Human Erythroid Progenitor Cells at Hypoxia Is Regulated by STAT5A and MEK Signaling but not HIFα

- Identification of DNA-Damage DNA-Binding Protein 1 as a Conditional Essential Factor for Cytomegalovirus Replication in Interferon-γ-Stimulated Cells

- The Influenza Virus Protein PB1-F2 Inhibits the Induction of Type I Interferon at the Level of the MAVS Adaptor Protein

- Passively Administered Pooled Human Immunoglobulins Exert IL-10 Dependent Anti-Inflammatory Effects that Protect against Fatal HSV Encephalitis

- Infection of Induces Antifungal Immune Defenses

- Merozoite Invasion Is Inhibited by Antibodies that Target the PfRh2a and b Binding Domains

- Cyclic di-GMP is Essential for the Survival of the Lyme Disease Spirochete in Ticks

- Cross-Neutralizing Antibodies to Pandemic 2009 H1N1 and Recent Seasonal H1N1 Influenza A Strains Influenced by a Mutation in Hemagglutinin Subunit 2

- Spatial Dynamics of Human-Origin H1 Influenza A Virus in North American Swine

- Coronavirus Gene 7 Counteracts Host Defenses and Modulates Virus Virulence

- Clathrin Facilitates the Morphogenesis of Retrovirus Particles

- Contribution of Intrinsic Reactivity of the HIV-1 Envelope Glycoproteins to CD4-Independent Infection and Global Inhibitor Sensitivity

- Functional Analysis of Host Factors that Mediate the Intracellular Lifestyle of

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- High Affinity Nanobodies against the VSG Are Potent Trypanolytic Agents that Block Endocytosis

- Structural and Mechanistic Studies of Measles Virus Illuminate Paramyxovirus Entry

- Sporangiospore Size Dimorphism Is Linked to Virulence of

- The Binding of Triclosan to SmeT, the Repressor of the Multidrug Efflux Pump SmeDEF, Induces Antibiotic Resistance in

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání