-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Global Health System: Actors, Norms, and Expectations in Transition

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 7(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000183

Category: Policy Forum

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000183Summary

article has not abstract

This is the first in a series of four articles that highlight the changing nature of global health institutions.

The Global Health System: A Time of Transition

The global health system that evolved through the latter half of the 20th century achieved extraordinary success in controlling infectious diseases and reducing child mortality. Life expectancy in low - and middle-income countries increased at a rate of about 5 years every decade for the past 40 years [1]. Today, however, that system is in a state of profound transition. The need has rarely been greater to rethink how we endeavor to meet global health needs.

We present here a series of four papers on one dimension of the global health transition: its changing institutional arrangements. We define institutional arrangements broadly to include both the actors (individuals and/or organizations) that exert influence in global health and the norms and expectations that govern the relationships among them (see Box 1 for definitions of the terms used in this article).

Box 1. Defining the Global Health System

We understand global health needs to include disease prevention, quality care, equitable access, and the provision of health security for all people [16]–[18]. We define the global health system as the constellation of actors (individuals and/or organizations) “whose primary purpose is to promote, restore or maintain health” [19], and “the persistent and connected sets of rules (formal or informal), that prescribe behavioral roles, constrain activity, and shape expectations” [20] among them. Such actors may operate at the community, national, or global levels, and may include governmental, intergovernmental, private for-profit, and/or not-for-profit entities.

The traditional actors on the global health stage—most notably national health ministries and the World Health Organization (WHO)—are now being joined (and sometimes challenged) by an ever-greater variety of civil society and nongovernmental organizations, private firms, and private philanthropists. In addition, there is an ever-growing presence in the global health policy arena of low - and middle-income countries, such as Kenya, Mexico, Brazil, China, India, Thailand, and South Africa.

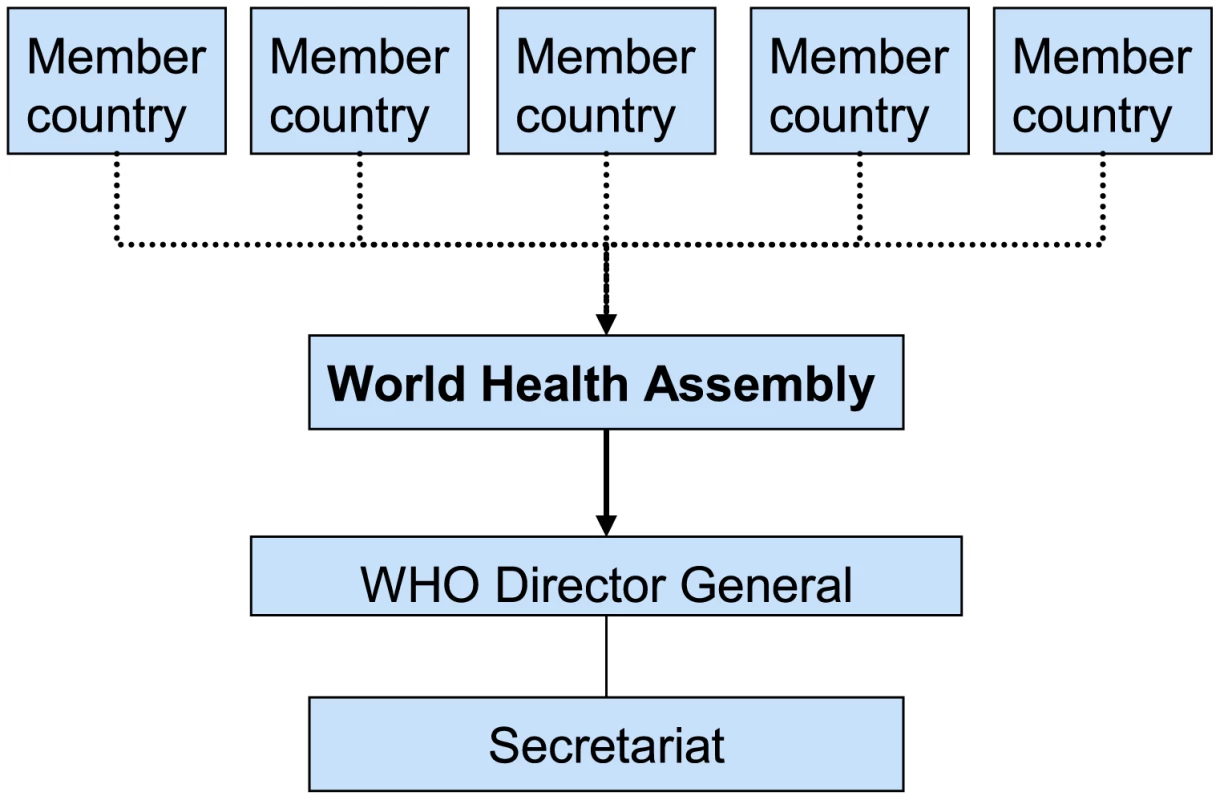

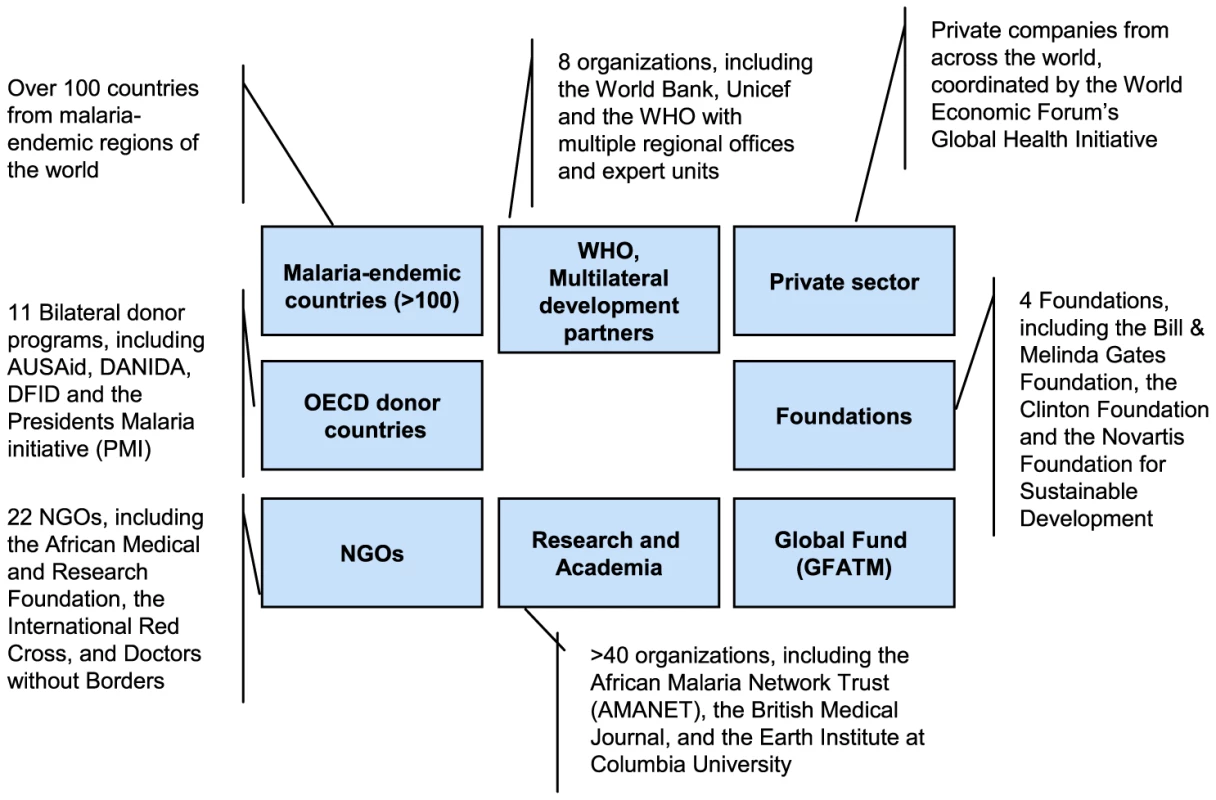

Also changing are the relationships among those old and new actors—the norms, expectations, and formal and informal rules that order their interactions. New “partnerships” such as WHO's Roll Back Malaria Partnership (RBM), Stop TB, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), and many others have come to exist alongside and somewhat independently of traditional intergovernmental arrangements between sovereign states and UN bodies (see Figures 1 and 2 for an illustration of the underlying governance principles). These partnerships have been emphasized—not least by WHO itself—as the most promising form of collective action in a globalizing world [2]. Large increases in international support for the newer institutions has led to relative and, in some cases, absolute declines in the financial importance of traditional actors [3].

Fig. 1. UN-type international health governance.

Based on the principles of the UN system, member countries are represented in the World Health Assembly (WHA), which functions as the central governing body. The WHA appoints the director general, oversees all major organizational decision making and approves the program budget. Fig. 2. Global Health as partnership.

Today's Roll Back Malaria Partnership consists of more than 500 partners, including the major players WHO, the Global Fund, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. RBM was initiated in 1998 by WHO, UNICEF, UNDP, and the World Bank. WHO currently hosts RBM's secretariat and contributes in multiple ways. However, it is not presented as the central node of the partnership (source: http://www.rollbackmalaria.org/). The rise of multiple new actors in the system creates challenges for coordination but, more fundamentally, raises tightly linked questions about the roles various organizations should play, the rules by which they play, and who sets those rules. Actors may exercise power within the constraints of international institutions in hopes of achieving benefits and shared objectives [4]. Such a calculus helps to explain why actors are willing to fund multilateral initiatives such as WHO, GFATM, RBM, and Stop TB, despite the fact that doing so entails relinquishing considerable control over what is done with their resources. On the other hand, powerful and financially independent actors, such as national governments, may elect to use their resources to influence the outcomes from multilateral initiatives or create bilateral ones. The lack of a clear set of rules that constrain distortion of priorities by powerful actors can threaten less powerful ones. As a case in point, despite widespread support for its overarching goals, there is considerable discussion, in some cases even unease and some tension, around the prominent role played by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, whose spending on global health was almost equal to the annual budget of WHO in 2007 [5]–[8].

Finally, this period of transition in actors and relationships comes at a time when the very nature of the challenges faced by health systems is itself being transformed. The success of child survival efforts has meant that noncommunicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and neuropsychiatric disease, are growing in prevalence alongside the continuing threats of communicable diseases [9]–[11]. The globalizing economy poses a new set of health challenges as the rules that govern trade in goods, services, and investment reach more deeply into national regulatory and health systems than have previous trade arrangements [12],[13]. Finally, changes in climate and other environmental variables are likely to create unexpected and unpredictable health threats, both as a direct result of changing environments for disease vectors and as an indirect result of impacts on water and food security, extreme events, and increased migration [14],[15].

The melee resulting from these interacting transitions has produced some extraordinary success stories, such as the drive that dramatically increased access to lifesaving antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV/AIDS, unprecedented access to insecticide-treated bednets for malaria, and enhanced access to anti-TB drugs in the developing world within a span of a few short years. But there is also mounting concern that the increasingly complex nature of the evolving global health system leaves unexploited significant opportunities for improving global health, results in duplication and waste of scarce health resources, and carries high transaction costs. The ongoing global financial crisis makes the efficient and effective performance of the global health system all the more pressing.

Many have expressed doubts that today's global health system is remotely adequate for meeting the emerging challenges of the 21st century [21]–[24]. A groundswell of opinion [25]–[35] suggests that new thinking is needed on whether or how practical reform of the present complex global health system can improve its ability to deal with such key issues as:

-

Setting global health agendas in ways that not only build upon the enthusiasm of particular actors, but also improve the coordination necessary to avoid waste, inefficiency, and turf wars.

-

Ensuring a stable and adequate flow of resources for global health, while safeguarding the political mobilization that generates issue-specific funding. How can the global burden of financing be equitably shared, and who decides? How should resources be allocated to meet the greatest health risks, particularly those that lack vocal advocates?

-

Ensuring sufficient long-term investment in health research and development (R&D). Who should contribute, and who should pay? How can the dynamism and capacity of both public and private sectors from North and South be harnessed, without compromising the public sector's regulatory responsibilities?

-

Creating mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation and judging best practices—how can policy agreement be achieved when actors bring contested views of the facts to the table?

-

Learning lessons from the enormous variance in effectiveness and costs of various national and international health systems, from R&D to the delivery and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of interventions in the field, to create improvements everywhere.

Roadmap of the Series

In this series we undertook a study of the role of institutions in the global health system. The aims of the study were threefold: first, to advance current understanding of the interplay of actors in the system; second, to evaluate its performance; and third, to identify opportunities for improvement. The project was part of a larger program led by Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government to advance thinking on the challenges of linking research knowledge with timely and effective action in an increasingly globalized and diverse world [36],[37]. It drew together theoretical literature on global governance that has emerged from the field of international relations over the last half-century [20],[38],[39]; on empirical analysis of institutional design and performance in other sectors that, similar to public health, seek to mobilize scientific knowledge as a global public good (e.g., agriculture and environmental protection [40]–[42]); and on the engagement of several of the authors of this paper in contemporary policy debates on ways to improve the institutions that promote global health [43],[44].

We focused on three central questions regarding the global health system: (1) What functions must an effective global health system accomplish? (2) What kind of arrangements can better govern the growing and diverse set of actors in the system to ensure that those functions are performed? (3) What lessons can be extracted from analysis of historical experience with malaria to inform future efforts to address them and the coming wave of new health challenges? To illuminate these questions, we built a series of case studies, workshops, and synthesis efforts, the results of which are reported in more detail elsewhere (http://www.cid.harvard.edu/sustsci/events/workshops/08institutions/index.html).

In the papers presented in this series we summarize representative results from our work for one key actor in, and one key function of, the global health system. Thus, the second article in the series, by Frenk [45], reflects on the essential characteristics of functioning national health systems, which are the anchoring institutions of the global health system. The continued crucial importance of national health systems as connectors of research and development with populations, and as guarantors of the successful and sustained delivery of health interventions to people and populations, is often overlooked in enthusiastic discussions of new approaches to the architecture of global health. Indeed, the biggest challenge facing global health today is to reconcile the ongoing global-level transformation with the need to further strengthen and support national-level health systems.

The third article, by Keusch et al. [46], examines how the global health system has evolved to better integrate the research, development, and delivery of health interventions—a core function of the system. We chose the global response to malaria as a good case study because of the long history of global efforts to combat the disease, multiple attempts at institution building in this domain, its recent rise on the global agenda, and the concomitant increase in resources devoted to combating it. Many old and new approaches have evolved and been tested in the field of malaria, including targeted programs like WHO's Malaria Action Programme and the WHO/UNDP/Unicef/World Bank Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) Programme; governance partnerships like RBM; product development partnerships such as the Medicines for Malaria Venture; and new delivery mechanisms such as GFATM. Goals have oscillated between global eradication, regional and national control, and now perhaps back to global eradication. Exploration of the evolution of institutional arrangements linking malaria research, development, and delivery hold important lessons for understanding the global health system more generally.

The fourth article of the series, by Moon et al. [47], presents conclusions regarding the three central questions raised above and poses questions for further research and recommendations for future action.

Our hope is that this series stimulates debate, encourages further case studies, and provides insights into general principles for the improvement of the global health system.

Zdroje

1. JamisonDT

2006 Investing in Health.

JamisonDT

BremanJG

MeashamAR

AlleyneG

ClaesonM

Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries Washington, D.C. World Bank 3 34

2. BrundtlandGH

2002 Address to the 55th World Health Assembly Geneva World Health Organization Available: http://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/2002/english/20020513_addresstothe55WHA.html. Accessed 6 September 2009

3. RavishankarN

GubbinsP

CooleyRJ

Leach-KemonK

MichaudCM

2009 Financing of global health: Tracking development assistance for health from 1990 to 2007. Lancet 373 2113 2124

4. KeohaneR

MartinL

1995 The Promise of Institutionalist Theory. Int Secur 20 39 51

5. McNeilDGJ

2008 March 4 Eradicate Malaria? Doubters Fuel Debate The New York Times Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/04/health/04mala.html. Accessed: 6 December 2009

6. The Lancet editors 2009 What has the Gates Foundation done for global health? Lancet 373 1577

7. McCoyD

KembhaviG

PatelJ

LuintelA

2009 The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation's grant-making programme for global health. Lancet 373 1645 1653

8. BlackRE

BhanMK

ChopraM

RudanI

VictoraCG

2009 Accelerating the health impact of the Gates Foundation. Lancet 373 1584 1585

9. BygbjergIC

MeyrowitschDW

2007 Global transition in health - secondary publication. Dan Med Bull 54 44 45

10. MathersCD

LoncarD

2006 Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3(11) e442 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

11. BloomBR

MichaudCM

La MontagneJR

SimonsenL

2006 Priorities for Global Research and Development of Interventions.

JamisonDT

BremanJG

MeashamAR

AlleyneG

ClaesonM

Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries Washington, D.C. World Bank

12. FidlerDP

DragerN

LeeK

2009 Managing the pursuit of health and wealth: The key challenges. Lancet 373 325 331

13. LeeK

SridharD

PatelM

2009 Bridging the divide: Global governance of trade and health. Lancet 373 416 422

14. CostelloA

AbbasM

AllenA

BallS

BellS

2009 Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute For Global Health Commission. Lancet 373 1693 1733

15. World Health Organization 2009 Protecting health from climate change: Global research priorities. Available: http://www.who.int/world-health-day/toolkit/report_web.pdf. Accessed 6 September 2009

16. KoplanJP

BondTC

MersonMH

ReddyKS

RodriguezMH

2009 Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 373 1993 1995

17. FrenkJ

2009 Strengthening health systems to promote security. Lancet 373 2181 2182

18. BrownTM

CuetoM

FeeE

2006 The world health organization and the transition from “international” to “global” public health. Am J Public Health 96 62 72

19. World Health Organization 2000 World Health Report 2000—Health Systems: Improving Performance. Available: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2009

20. KeohaneRO

1984 After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy Princeton (New Jersey) Princeton University Press

21. AdeyiO

SmithO

RoblesS

2007 Public Policy and the Challenge of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases Washington, D.C. World Bank 218

22. BeagleholeR

EbrahimS

ReddyS

2007 Prevention of chronic diseases: A call to action. Lancet 370 2152 2157

23. EvansT

2004 The G-20 and Global Public Health. CIGI/CFGS, The G-20 at Leaders' Level? Ottawa IDRC Available: http://www.l20.org/publications/23_fZ_ottawa_conference_report.pdf. Accessed 6 September 2009

24. JamisonDT

BremanJG

MeashamAR

AlleyneG

ClaesonM

2006 Priorities in Health Washington, D.C. The World Bank 221

25. BrughaR

WaltG

2001 A global health fund: A leap of faith? BMJ 323 152 154

26. CohenJ

2006 Global health. Public-private partnerships proliferate. Science 311 167

27. GodalT

2005 Do we have the architecture for health aid right? Increasing global aid effectiveness. Nat Rev Microbiol 3 899 903

28. HaleVG

WooK

LiptonHL

2005 Oxymoron no more: The potential of nonprofit drug companies to deliver on the promise of medicines for the developing world. Health Aff (Millwood) 24 1057 1063

29. KaulI

FaustM

2001 Global public goods and health: taking the agenda forward. Bull World Health Organ 79 869 874

30. LambertML

van der StuyftP

2002 Editorial: Global health fund or global fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria? Trop Med Int Health 7 557 558

31. PokuNK

WhitesideA

2002 Global health and the politics of governance: an introduction. Third World Q 23 191 195

32. SchneiderCH

2008 Global public health and international relations: pressing issues – Evolving governance. Aust J Int Aff 62 94 106

33. GostinLO

2007 Meeting the survival needs of the world's least healthy people - A proposed model for global health governance. JAMA 298 225 228

34. LeeK

2006 Global health promotion: How can we strengthen governance and build effective strategies? Health Promot Int 21 42 50

35. TuckerTJ

MakgobaMW

2008 Public-private partnerships and scientific imperialism. Science 320 1016 1017

36. EllwoodD

2008 Acting in time: overview of the initiative. Available: http://www.hks.harvard.edu/about/admin/offices/dean/ait/overview. Accessed 6 September 2009

37. NyeJS

DonahueJD

2000 Governance in a globalizing world Washington, D.C. Brookings Institution Press 386

38. OstromE

2005 Understanding institutional diversity Princeton (New Jersey) Princeton University Press 355

39. RuggieJG

1982 International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Postwar Economic Order. Int Organ 36(2)

40. CashDW

ClarkWC

AlcockF

DicksonNM

EckleyN

2003 Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(14) 8086 8091

41. RuttanVW

BellDE

ClarkWC

1994 Climate-change and food security—agriculture, health and environmental research. Glob Environ Change 4 63 77

42. ClarkWC

MitchellRB

CashDW

2006 Global Environmental Assessments: Information and Influence.

MitchellRB

ClarkWC

CashDW

DicksonNM

Evaluating the influence of global environmental assessments Cambridge (Massachusetts) MIT Press 1 28

43. KeuschGT

MedlinCA

2003 Tapping the power of small institutions. Nature 422 561 562

44. MorelCM

AcharyaT

BroundD

DangiA

EliasC

2005 Health innovation networks to help developing countries address neglected diseases. Science 309 401 404

45. FrenkJ

2010 The Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems as the Next Step for Global Progress. PLoS Med In press

46. KeuschG

KilamaW

MoonS

SzlezákN

MichaudC

2010 The Global Health System: Linking Knowledge with Action - Learning from Malaria. PLoS Med In press

47. MoonS

SzlezákN

MichaudC

JamisonD

KeuschG

2010 The Global Health System: Lessons for a Stronger Institutional Framework. PLoS Med In press

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 1- Berberin: přírodní hypolipidemikum se slibnými výsledky

- Léčba bolesti u seniorů

- Příznivý vliv Armolipidu Plus na hladinu cholesterolu a zánětlivé parametry u pacientů s chronickým subklinickým zánětem

- Jak postupovat při výběru betablokátoru − doporučení z kardiologické praxe

- Červená fermentovaná rýže účinně snižuje hladinu LDL cholesterolu jako vhodná alternativa ke statinové terapii

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Quantifying the Number of Pregnancies at Risk of Malaria in 2007: A Demographic Study

- The Global Health System: Actors, Norms, and Expectations in Transition

- Microscopy Quality Control in Médecins Sans Frontières Programs in Resource-Limited Settings

- The Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems as the Next Step for Global Progress

- Meeting the Demand for Results and Accountability: A Call for Action on Health Data from Eight Global Health Agencies

- Relationship between Vehicle Emissions Laws and Incidence of Suicide by Motor Vehicle Exhaust Gas in Australia, 2001–06: An Ecological Analysis

- The Global Health System: Lessons for a Stronger Institutional Framework

- Geographic Distribution of Causing Invasive Infections in Europe: A Molecular-Epidemiological Analysis

- The Global Health System: Linking Knowledge with Action—Learning from Malaria

- The Relationship between Anti-merozoite Antibodies and Incidence of Malaria: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Neonatal Circumcision for HIV Prevention: Cost, Culture, and Behavioral Considerations

- “Working the System”—British American Tobacco's Influence on the European Union Treaty and Its Implications for Policy: An Analysis of Internal Tobacco Industry Documents

- The Evolution of the Epidemic of Charcoal-Burning Suicide in Taiwan: A Spatial and Temporal Analysis

- Mapping the Distribution of Invasive across Europe

- Science Must Be Responsible to Society, Not to Politics

- Are Patents Impeding Medical Care and Innovation?

- Male Circumcision at Different Ages in Rwanda: A Cost-Effectiveness Study

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The Evolution of the Epidemic of Charcoal-Burning Suicide in Taiwan: A Spatial and Temporal Analysis

- Male Circumcision at Different Ages in Rwanda: A Cost-Effectiveness Study

- Geographic Distribution of Causing Invasive Infections in Europe: A Molecular-Epidemiological Analysis

- “Working the System”—British American Tobacco's Influence on the European Union Treaty and Its Implications for Policy: An Analysis of Internal Tobacco Industry Documents

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání