-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaLoss of UCP2 Attenuates Mitochondrial Dysfunction without Altering ROS Production and Uncoupling Activity

Mitochondria produce the majority of the energy needed for numerous cell functions through oxidative phosphorylation. However, this comes with the cost in the form of potentially harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) that could damage all kinds of biological macromolecules. Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential through mild uncoupling could alter ROS production in the cell (“uncoupling to survive”). Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are believed to play a central role in this process. We detected increased amounts of UCP2 in mtDNA mutator mice, a model for premature aging. Depletion of UCP2 in mtDNA mutator mice led to further shortening of the lifespan with earlier signs of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy accompanied with high systemic lactic acidosis, often used as a marker of mitochondrial diseases. Remarkably, our results demonstrate that the presence of UCP2 wields beneficial effect on respiratory deficient mitochondria without affecting ROS production or uncoupling. Instead, UCP2 protein seems to mediate a valuable upregulation of fatty acid metabolism detected in mtDNA mutator hearts. Our results provide a novel mechanism of adaptation of mitochondria to respiratory deficiency mediated by UCP2 that clearly argues against the “uncoupling to survive” theory.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004385

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004385Summary

Mitochondria produce the majority of the energy needed for numerous cell functions through oxidative phosphorylation. However, this comes with the cost in the form of potentially harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) that could damage all kinds of biological macromolecules. Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential through mild uncoupling could alter ROS production in the cell (“uncoupling to survive”). Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are believed to play a central role in this process. We detected increased amounts of UCP2 in mtDNA mutator mice, a model for premature aging. Depletion of UCP2 in mtDNA mutator mice led to further shortening of the lifespan with earlier signs of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy accompanied with high systemic lactic acidosis, often used as a marker of mitochondrial diseases. Remarkably, our results demonstrate that the presence of UCP2 wields beneficial effect on respiratory deficient mitochondria without affecting ROS production or uncoupling. Instead, UCP2 protein seems to mediate a valuable upregulation of fatty acid metabolism detected in mtDNA mutator hearts. Our results provide a novel mechanism of adaptation of mitochondria to respiratory deficiency mediated by UCP2 that clearly argues against the “uncoupling to survive” theory.

Introduction

Mitochondria are organelles found in almost every eukaryotic cell. They produce the bulk of cellular energy in the form of ATP, which is required for numerous processes in the cell. Still, mitochondrial energy production comes with a cost, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that is linked to the development of different pathologies and is proposed to contribute to aging [1]. The mitochondrial theory of aging proposes that an age-driven accumulation of mtDNA mutations will compromise electron transport leading to an increase in ROS production [1]. We challenged this theory by showing that increased levels of random mtDNA mutations lead to the development of premature aging phenotypes in mtDNA mutator mice, without affecting ROS production or increasing oxidative stress [2], [3]. Our result argues against a direct link between mtDNA mutations and increased ROS production, but can also point out to the consequence of an active compensatory mechanism. A mild uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, leading to decreased mitochondrial ATP production could be sufficient to reduce ROS generation in the cell [4]. The “uncoupling to survive” theory further suggests that mitochondrial inefficiency mediated by partial uncoupling could have a beneficial effect on aging [4]. Uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are proposed to have a central role in this process (for review see [5]).

The mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are located in the mitochondrial inner membrane where they could act as regulated protonophores. The term “uncoupling protein” was originally used for UCP1, a brown fat specific proton carrier that dissipates the proton gradient as heat [6]. It was anticipated that UCP2 and UCP3 lead to a moderate uncoupling that is believed to modulate the ATP/ADP ratio for signalling purposes, but their precise function in normal cellular physiology is still unclear [7]. These proteins are found in much lesser amounts than UCP1 and might be involved in the proton conductance only upon activation leading to the conclusion that they are not involved in the adaptive response to cold [7]. Emerging evidence suggests that UCP2 plays a positive physiological role by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis, substrate utilization, and ROS elimination; thereby, provides neuroprotective [8] and possibly anti-aging effects [9]. Nevertheless, several studies indicated that UCP2 could have deleterious effects on cellular function, like in the development of insulin resistance and the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus [10].

In this study we detected increased amounts of UCP2 in multiple tissues of mtDNA mutator mice. We show that UCP2 has a protective role against molecular changes leading to a progressive cardiomyopathy and complete loss of this protein leads to further shortening of the lifespan in mtDNA mutator mice. However, UCP2 exercises its beneficial effect without affecting ROS production or modulating proton leak kinetics in heart. Instead, we provide evidence for a novel mechanism by which increased UCP2 levels modulate cardiac metabolism to maintain proficient energy production, challenged by progressive respiratory deficiency.

Results

UCP2 levels are increased in mtDNA mutator mice and depletion of this protein leads to further lifespan shortening

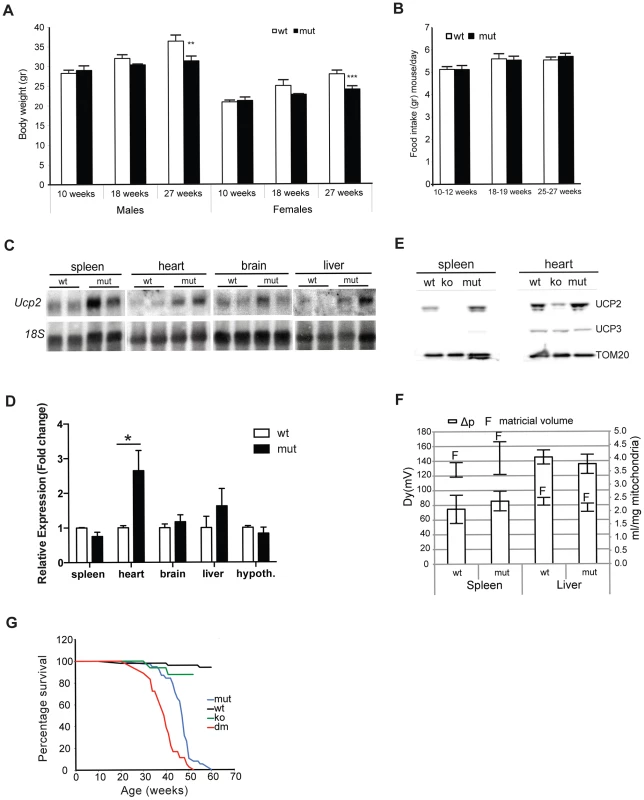

One of the first symptoms of premature aging in mtDNA mutator mice is cessation in weight gain around 18–25 weeks of age, followed by a progressive loss of body mass with increasing age [2]. Indeed, we detected a significant difference in the body weight in male and female mtDNA mutator mice already at 18 weeks of age that was even more pronounced at 25–27 weeks of age (Figure 1A). Both individually and group-housed mtDNA mutator mice maintained on a regular chow diet showed normal daily food intake at different time points that included measuring food consumption over periods of several weeks (2–3 weeks) (Figure 1B). Although we cannot completely exclude the possibility that mtDNA mutator mice had decreased food intake at some point between these measurements, we believe this to be unlikely. During our early screening for changes in gene expression, we noticed that the expression of Ucp2 is increased in some tissues of mtDNA mutator mice, most prominently in heart (Figure 1C and 1D). The increase in Ucp2 mRNA levels was mirrored by an increase in the UCP2, but not UCP3, protein levels in heart and spleen (Figure 1E). Interestingly, we failed to observe an increase in Ucp2 transcript levels in spleen by quantitative real-time PCR, although we observed clear upregulation of protein levels (Figure 1D and 1E, respectively). This could be the consequence of increased UCP2 stability in spleen.

Fig. 1. MtDNA mutator mice have lower body mass and upregulated UCP2 levels.

Body weight (A) and daily food consumption (B) in mtDNA mutator (mut) mice in comparison to littermate controls (wt) (n = 11). (C) Northern blot analyses of Ucp2 levels in spleen, heart, brain and liver. (D) Fold change of Ucp2 transcript levels in spleen, heart, brain, liver and hypothalamus for wt and mut (n = 4). (E) Western blot analyses of UCP2 in spleen and heart mitochondria of wt, mut and UCP2-deficient (ko) mice. (F) Proton motive force (bars) and mitochondrial matrix volume (lines) in liver and spleen mitochondria (n = 3). (G) Mean lifespan of wt, mut, ko and dm mice. All analyses were performed on 25-week-old mice. Bars indicate mean level ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Asterisks indicate level of statistical significance (*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001, Student's t-test). Inefficient energy use caused by the uncoupling of mitochondrial respiration could lead to the observed imbalance between food intake and energy expenditure in mtDNA mutator mice. An increased energy expenditure and lower body mass were observed in mice overexpressing human UCP3 protein specifically in skeletal muscle [11].

In order to assess whether the UCP2 upregulation leads to an increased proton leak, we measured proton motive force (Δp) in both liver and spleen mitochondria (Figure 1F). These two tissues represent the real opposites when it comes to the UCP2 levels: while splenocytes contain the highest level of UCP2, the transcripts detected in liver preps originate from the Kupffer cells, which are resident liver macrophages, as it was shown that hepatocytes do not express UCP2 [12]. Despite the upregulation of UCP2 levels in mtDNA mutator mitochondria isolated from spleen, we could not observe a difference in the Δp between the two genotypes indicating that UCP2 does not contribute significantly to the proton leak in these conditions (Figure 1F). We also show that mitochondrial matricial volume, on which Δp is dependent, was not significantly changed (Figure 1F). Our results demonstrate that liver mitochondria have a higher proton motive force than spleen mitochondria (Figure 1F), in agreement with a previous report showing that spleen mitochondria have the highest and liver the lowest proton leak [13].

To further address the specific role of UCP2 in mitochondrial dysfunction caused by an increased mtDNA mutation load, we have crossed mtDNA mutator mice with UCP2-deficient mice (KO), producing PolgAmut/mut; Ucp2−/− double mutant mice (hereafter DM mice). The mean lifespan of mtDNA mutator mice was on average 14% shorter in the absence of UCP2 (DM – 39.1±4.4 weeks v. mtDNA mutator 46.4±5.3 weeks), indicating that UCP2 overexpression provides some form of beneficial adaptive change (Figure 1G). It was previously shown that UCP2-deficient mice have a significantly shorter lifespan than wild type controls [14], therefore, at this point it is difficult to distinguish if the shorter lifespan reflects a specific interaction or just an additive effect of UCP2 deficiency in mtDNA mutator mice.

mtDNA mutator mice display a fasting-like phenotype that is not affected by the loss of UCP2

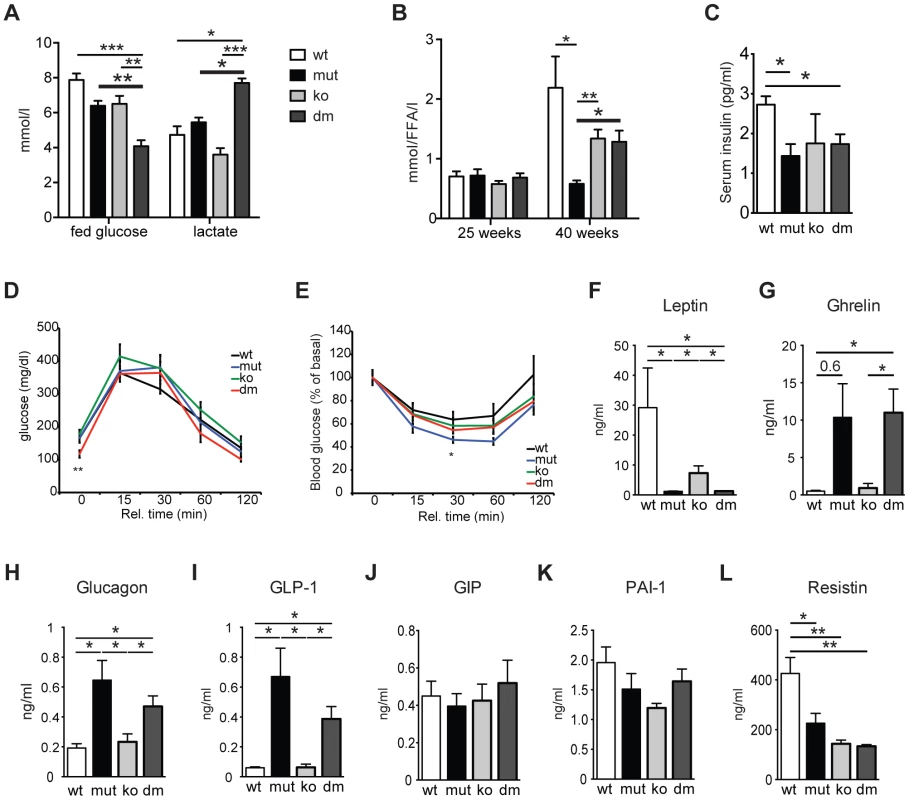

Recent advancements in the understanding of cellular glucose and lipid metabolism identified UCP2 as a critical regulator of cellular fuel utilization and whole body glucose and lipid metabolism (for review see [15]). Therefore, we investigated the impact of UCP2 depletion on energy metabolism in mtDNA mutator mice. We observed a significant reduction in body weight in both, mtDNA mutator and DM mice at 20 weeks of age (Figure S1A – S1C). Interestingly, the oxygen consumption, energy expenditure and respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were increased only in DM mice (Figure S1D - S1G). This was accompanied by a twofold decrease in blood glucose levels and a high increase in circulating lactate levels exclusively in DM mice (Figure 2A). Taken together these data suggest that the loss of UCP2 promotes preferential usage of glucose as energy source in DM mice. Indeed, UCP2 has previously been shown to promote mitochondrial FAO while limiting mitochondrial catabolism of pyruvate originating from glucose [16]. In agreement with this, mtDNA mutator mice failed to increase circulating free fatty acid (FFA) levels at 40 weeks of age probably owing to exhaustion of lipid stores as a result of increased FAO enabled by high UCP2 upregulation (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. Characterization of blood metabolites in wild type (wt), mtDNA mutator (mut), UCP2-deficient wild type (ko) and mtDNA mutator (dm) mice.

(A) Blood glucose and lactate concentrations at 25 weeks of age. (n = 6). (B) Circulating free fatty acid levels in 25- and 40-week-old animals. (n = 5–6). (C) Serum insulin levels of 30-week-old mice. (D) Glucose tolerance test in 30-week-old mice. After 16 hours of starvation period, mice were injected with 2g/kg body weight glucose and clearance was measured after 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes (n = 7). (E) Insulin tolerance test of 30-week-old random fed mice. Mice were injected with 0.75 U/kg body weight of insulin and glucose levels were measured after 0, 15, 30 60 and 120 minutes (n = 7). (F–L) Analyses of metabolic markers in the serum: (F) Leptin; (G) Ghrelin; (H) Glucagon; (I) Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1); (J) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP); (K) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1); (L) Resistin. All measurements were performed in 30-week-old mice. (n = 4). Bars indicate mean levels ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistically significant differences between mut and dm are presented with thick lines. Asterisks indicate level of statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.001, Student's t-test). UCP2 was shown to be a negative regulator of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) through control of ROS production that plays an important signaling role in insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells [10], [17]. We detected a small but significant decrease in serum insulin levels in both mtDNA mutator and DM animals at 30 weeks of age (Figure 2C). Although an initial report using mice on a mixed background suggested that UCP2-deficient mice have higher serum insulin levels [10], it was recently shown that UCP2-deficient pancreatic β cells have reduced GSIS [17]. Our data further support this finding, as we have found normal serum insulin levels in KO mice (Figure 2C). Consistent with this, glucose tolerance was similar in all different groups, although DM animals started with lower fasting glucose levels (Figure 2D). Similarly, insulin sensitivity was comparable between all groups of animals (Figure 2E). Hence, our data indicate that UCP2 depletion in mtDNA mutator mice does not significantly change systemic glucose metabolism.

Analyses of other metabolic markers revealed that mtDNA mutator and DM mice show similar changes in the levels of different hormones involved in energy balance. We detected decreased levels of serum leptin, a central satiety agent (Figure 2F), while levels of ghrelin, a hunger-stimulating hormone were upregulated in both mtDNA mutator and DM mice (Figure 2G). It was previously shown that ghrelin acts by inducing UCP2-dependent changes of hypothalamic mitochondrial proliferation and respiration that are critical for the activation of different neurons involved in signaling of ghrelin-induced food intake [18]. Despite an increase in circulating ghrelin levels, we have not detected changes in UCP2 transcript levels in hypothalamus of mtDNA mutator mice (Figure 1D). It is possible that chronic induction of ghrelin does not affect UCP2 expression in hypothalamus, or the observed increase in circulating ghrelin levels is too low to induce this kind of change. Therefore, we believe that the changes induced by mitochondrial dysfunction do not affect the hypothalamic circuitry and feeding behaviour differently in mtDNA mutator and DM mice.

We have also found higher levels of glucagon and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) (Figure 2H and 2I) that increase during prolonged periods of fasting and usually show inverted relation to serum insulin levels [19]. A synergism of low insulin and relative or absolute elevation of glucagon levels is viewed as a hormonal mechanism controlling the rate of hepatic substrate extraction for gluconeogenesis [19]. Finally, we also detected decreased levels of Resistin/RETN (Figure 2L), an adipose-secreted hormone linked to obesity and insulin resistance in rodents [20]. It was previously shown that the Resistin expression from adipose tissue and its serum levels are reduced in fasted mice [20]. We have not observed changes in the level of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) (Figure 2J), indicating normal intestinal nutrient absorption [21], or plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (Figure 2K) that is linked to glucose intolerance and inflammation [22]. Taken together, these data show that mitochondrial dysfunction caused by increased mtDNA mutations induces a systemic fasting-like situation that is not significantly changed by UCP2 deficiency.

Loss of UCP2 activates stress-induced markers and attenuates cardiac phenotypes in mtDNA mutator mice

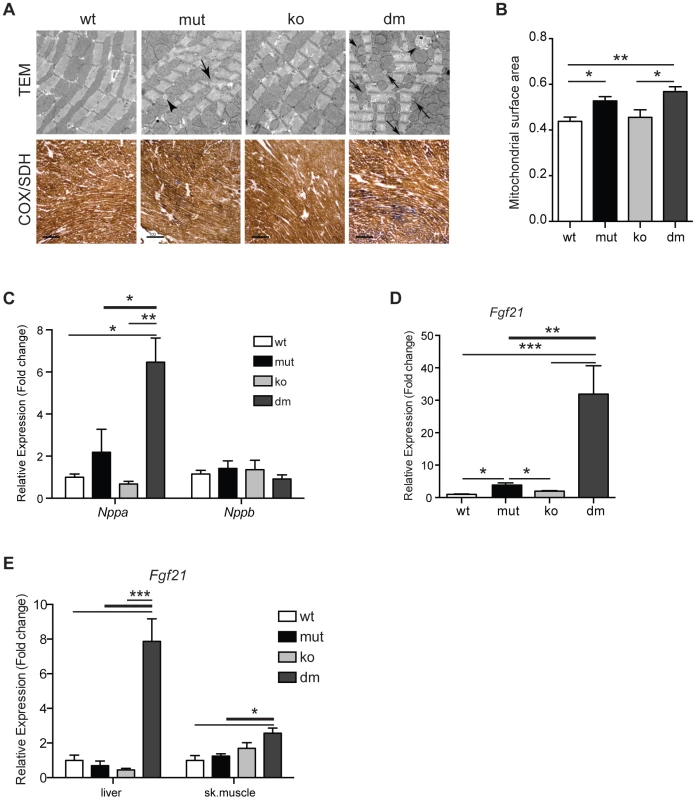

Puzzled by our initial observation of decreased mean and maximal lifespan in DM mice, we proceeded to look more closely into changes caused by UCP2 depletion in heart, as this was the tissue with the strongest upregulation of UCP2 levels (Figure 1D) and dilated cardiomyopathy was recognized as one of the most prominent changes in mtDNA mutator mice [2]. Ultrastructural analyses of DM hearts revealed the accumulation of unusually shaped mitochondria and lipid droplets accompanied by an increase in mitochondrial mass already at 25 weeks of age (Figure 3A and 3B). We also observed a milder increase in mitochondrial mass in mtDNA mutator cardiomyocytes (Figure 3B). Upregulation of mitochondrial mass is a common compensatory mechanism opposing decreased mitochondrial function and is detected in different animal models and patients with mitochondrial diseases [23], [24]. Enzyme histochemical staining (COX-SDH) of heart sections revealed a higher incidence of mitochondrial deficiency in cardiomyocytes of DM mice at this age (Figure 3A). This suggests that high levels of UCP2 protect mtDNA mutator hearts from early respiratory deficiency and postpone pathological changes to a later age [2]. In agreement with this, we observed that levels of the natriuretic peptide precursor type A (Nppa), one of most commonly used marker of cardiac hypertrophy tripled in mtDNA mutator hearts after UCP2 depletion highlighting a progression of mitochondrial dysfunction in DM mice (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3. Characterization of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy in wild type (wt), mtDNA mutator (mut), UCP2-deficient wild type (ko) and mtDNA mutator (dm) mice.

(A) Histological examination of cardiomyocytes from mut and dm mice. TEM – transmission electron micrographs. Arrows indicate lipid droplets, arrowheads abnormal mitochondria. COX/SDH - Enzyme histochemical staining for cytochrome c oxidase (COX) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activities in heart. (B) Quantification of mitochondrial mass in transmission electron micrographs. (C) Relative expression levels of Nppa and Nppb, markers of heart failure. (D) Relative Fgf21 mRNA expression levels in heart. (E) Relative Fgf21 mRNA expression levels in liver and skeletal muscle. All analyses were performed on 25-week-old mice. Bars indicate mean level ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Asterisks indicate level of statistical significance (*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001, Student's t-test). Recently, it was shown that respiratory chain deficiency induces a mitochondrial stress response, marked by increased levels of FGF21 (Fibroblast growth factor 21), that directly correlate with the severity of mitochondrial dysfunction [25]. Expression of Fgf21 in heart was also shown to have an important cardioprotective role [26]. Our latest results indicate that FGF21 could act as an initial signal that senses disrupted mitochondrial proteostasis in heart and activate different stress responses independent of respiratory chain deficiency [27]. Now, we observed an upregulation of Fgf21 transcripts that was by an order of magnitude higher after UCP2 depletion in mtDNA mutator mice, signifying a more severe problem in DM hearts (Figure 3D). FGF21 is a cytokine that acts through autocrine or paracrine signaling and its main sources are thought to be liver, skeletal muscle and adipocytes [28]. Therefore, we also analyzed expression levels of Fgf21 in liver and skeletal muscle. Mirroring the situation in heart, we found an upregulation of Fgf21 levels in both liver and skeletal muscle exclusively in DM animals (Figure 3E). Upregulation of Fgf21 levels in skeletal muscle is also detected in mtDNA mutator mice, but not before 37–40 weeks of age [29]. These results further support our conclusion that mtDNA mutator animals are under higher stress upon UCP2 depletion.

We also analysed cardiac function of mtDNA mutator mice before and after UCP2 depletion in vivo by high-resolution MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) in 18 - to 20-week-old mice. Although we observed only mild changes in functional cardiac parameters, they were prevalent in DM mice (Figure S2).

UCP2 depletion does not affect oxidative stress nor increases proton leak in mtDNA mutator hearts

Next we characterized the respiratory chain function in hearts of DM mice because of the findings of focal cytochrome c oxidase deficiency and increased mitochondrial mass in some cardiomyocytes (Figure 3). Our results show an additional decrease in complex I and IV respiratory chain enzyme activities in DM mice (Figure S3A). Even activity of complex II, the only mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) complex not affected in mtDNA mutator mice, was decreased, suggesting the existence of a general (toxic) effect of UCP2 deficiency on all respiratory chain complexes (Figure S3A). This was accompanied by a further 12–20% decrease in the mitochondrial ATP production rates (MAPR) in DM heart mitochondria incubated with different substrates (Figure S3B).

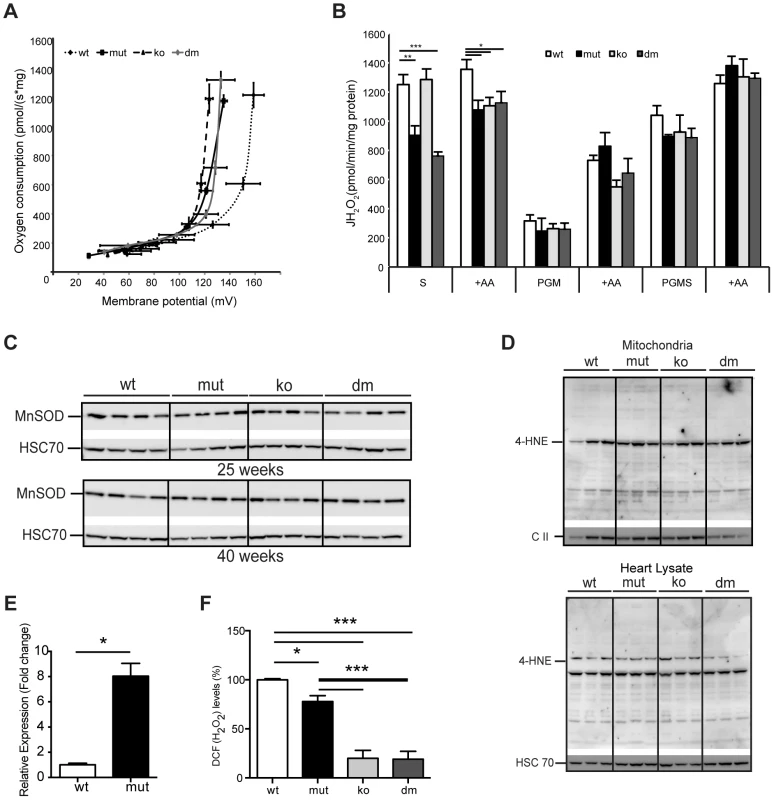

In order to understand why the loss of UCP2 leads to higher respiratory deficiency in mtDNA mutator mice, we examined the proton leak kinetics in heart mitochondria (Figure 4A). Our analysis showed that both resting oxygen consumption and membrane potential were normal in mtDNA mutator mice regardless of the presence of UCP2 (Figure 4A), indicating that UCP2 or increased levels of mtDNA mutations [2] do not affect proton leak kinetics in heart mitochondria of mtDNA mutator mice.

Fig. 4. UCP2 deficiency does not affect proton leak kinetics or ROS production.

(A) Flow-force relationship in heart mitochondria of 25-week-old wild type (wt), mtDNA mutator (mut), UCP2-deficient wild type (ko) and mtDNA mutator (dm) mice examined in the presence of succinate and increasing amounts of malonate (n = 6). Data points indicate mean levels ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). (B) Hydrogen peroxide production rate in heart mitochondria in the presence of succinate (S); Pyruvate-Glutamate-Malate (PGM) or Pyruvate-Glutamate-Malate-Succinate (PGMS) as substrates. Measurement in the presence of succinate alone detects reverse flow ROS production from both Complex I and Complex III. When mitochondria are incubated in the presence of pyruvate-glutamate-malate (PGM), the ROS production mainly originates from complex III and therefore it is usually lower. Treatment with Antimycin A (+AA), an inhibitor of CO III, was used as a positive control, to further induce ROS production (n = 4–5). Bars indicate mean level ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). (C) Western blot analyses of Manganese Superoxide Dismutase (MnSOD) in heart lysates of 25- and 40-week-old mice (n = 4). (D) Analysis of 4-Hydroxynonenal as measure for oxidative stress induced lipid peroxidation in isolated mitochondria (upper panel) and tissue lysates (lower panel) of 25-week-old mouse hearts. The mitochondrial Complex II 70 kDa protein (C II) was used as loading control in isolated mitochondria and the Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 (HSC 70) in heart tissue lysates (n = 4). (E) Fold change of Ucp2 transcript levels in primary MEFs (P1–P3). (F) ROS production in intact cells was assessed by flow cytometric analyses of primary (passage 1–3) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) stained with CM-H2DCFDA that upon oxidation by ROS, particularly hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical (·OH), yields the fluorescent DCF product. Data are expressed as median values of fluorescence intensity ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Asterisks indicate level of statistical significance (*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001, Student's t-test). Mild uncoupling was proposed to significantly decrease ROS production in mitochondria [4]. Our initial hypothesis was that an eminent UCP2 overexpression has a protective role against a deleterious increase in ROS production. Therefore, we next determined net H2O2 production in isolated mitochondria. MtDNA mutator mitochondria, regardless of the presence or absence of UCP2, produced significantly less ROS than the wild type, when energized by succinate, and normal ROS levels, when we used mixed substrates that allow a maximal rate of mitochondrial respiration (Figure 4B). Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production often leads to compensatory upregulation of antioxidant responses in the cell. However, we found no evidence for the activation of oxidative stress responses, measured by the expression levels of different mitochondrial ROS scavenging enzymes (Figure S4A) and SOD2 protein levels (Figure 4C) in mtDNA mutator or DM mice at 25 and 40 weeks of age, consistent with our previous findings [3]. In addition, we did not detect increased oxidative stress in mtDNA mutator animals regardless of the presence of UCP2, as shown by normal levels of protein carbonyls (Figure S4B) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) (Figure 4D). The ROS production in intact cells was measured in mouse embryonic fibroblasts that presented a high increase in Ucp2 levels (Figure 4E), as our multiple efforts to isolate adult cardiomyocytes, especially from mtDNA mutator and DM animals, failed. We found a small decrease in ROS production in mtDNA mutator MEFs and a much stronger reduction in both UCP2 KO and DM cells (Figure 4F). Taken together, these results strongly indicate that UCP2 depletion in mtDNA mutator mice does not lead to an increase in ROS production or oxidative damage, and UCP2 upregulation is not a compensatory mechanism against increased oxidative stress.

Loss of UCP2 decreases fatty acid oxidation in mtDNA mutator heart mitochondria

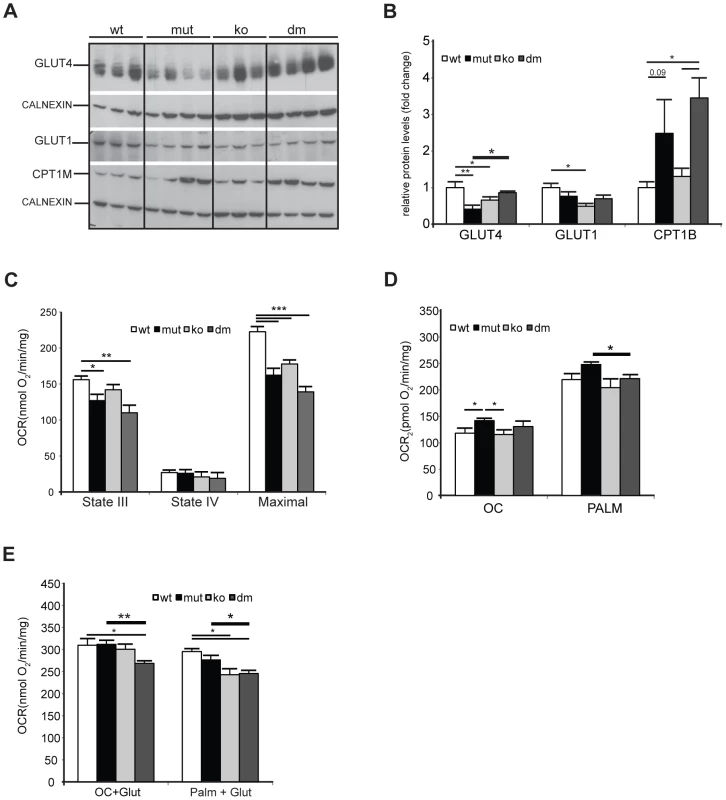

We next looked for an alternative role that UCP2 could play in mtDNA mutator hearts. Under normal conditions, the heart generates ATP by the consumption of energy substrates, mainly fatty acids (roughly 70%) with glucose and lactate contributing to the rest [30]. The rate of mitochondrial FAO is dependent on the level of fatty acids transported into mitochondria by Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 1 (muscle) - CPT1B, a mitochondrial enzyme associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane that mediates the transport of long-chain fatty acids across the membrane by binding them to carnitine. We detected a two to threefold increase in CPT1B levels in both mtDNA mutator and DM hearts pointing to an increased FFA uptake into heart mitochondria of both mutants (Figure 5A–B). The levels of the insulin-regulated glucose transporter, GLUT4, was two times lower in mtDNA mutator hearts, and was normalized upon UCP2 depletion (Figure 5A–B). The levels of GLUT1, a constitutively expressed glucose transporter, were not changed in mtDNA mutator or DM mitochondria (Figure 5A–B). These results demonstrate that mitochondrial dysfunction in mtDNA mutator mice increases the FFA uptake into heart mitochondria, while decreasing glucose uptake. Simultaneously, UCP2 upregulation allows higher or more efficient fatty acid oxidation. In the case of UCP2 deficiency combined with mitochondrial dysfunction, increased fatty acid uptake results in increased lipid accumulation inside cardiomyocytes, as observed in DM mice (Figure 3A). The defect in lipid handling in DM mice was further supported by changes in the expression of several genes involved in FFA transport and FAO in mitochondria like: Cpt2 (Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 2), Cact (Carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase), Acot10 (Acyl-CoA thioesterase 10) and Lpl (Lipoprotein lipase) (Figure S5A). Additionally, we observed an increase in the levels of Fatp1 (Long-chain fatty acid transport protein 1) and Fabp3 (Fatty acid binding protein 3, muscle), proteins that are involved in the cellular uptake of long-chain fatty acids [31], [32], only in DM hearts (Figure S5A).

Fig. 5. UCP2 promotes fatty acid oxidation in mtDNA mutator mitochondria.

(A) Steady-state levels of mitochondrial glucose and fatty acid transporters: insulin-regulated glucose transporter (GLUT4), basal glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1B) in wild type (wt), mtDNA mutator (mut), UCP2-deficient wild type (ko) and mtDNA mutator (dm) mice. Cytoplasmic calnexin was used as loading control. (B) Quantification of Western blots from (A). (C) Oxygen consumption rates in intact mitochondria in presence of pyruvate-glutamate-malate as substrates. State III (substrates+ADP); State IV (+oligomycin); MAX (+CCCP). (D) Oxygen consumption rates in intact mitochondria in the presence of medium (OC - octanoyl-carnitine) or long chain (PALM - palmitoyl-carnitine) fatty acids as substrates. (E) Maximal oxygen consumption rates upon addition of octanoyl-carnitine+glutamate (OC+Glut) or palmitoyl-carnitine+glutamate (PALM+Glut) to intact mitochondria. (n = 4–6). Bars indicate mean levels ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistically significant differences between mut and dm are presented with thick lines. Asterisks indicate level of statistical significance (*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001, Student's t-test). We next looked at the expression of genes involved in glycolysis and found an increase in Pdk4 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 4) levels in mtDNA mutator hearts that was highly augmented upon UCP2 depletion (Figure S5B). PDK4 is an enzyme that inactivates the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) and therefore prevents the usage of pyruvate. This is crucial for the conservation of 3-C compounds for glucose synthesis when glucose is scarce [33] and could be a consequence of the high lactic acidosis observed in DM mice (Figure 2A).

To dissect the mechanism by which UCP2 regulates the metabolism of mtDNA mutator mice, we examined the metabolic capacity of isolated mitochondria using different substrates in the presence of ADP (State III): complex I (glutamate/malate) or fatty acids (octanoyl-carnitine or palmitoyl-carnitine) (Figure 5C and 5D, respectively). We also measured State IV, which represents the oxygen consumption not linked to ATP synthesis, i.e., respiration due to uncoupling (Figure 5C). In the presence of complex I substrates, oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in both inducible states (State III and maximal respiration) were decreased in mtDNA mutator and DM mice (Figure 5C). The respiratory control ratio (RCR), an index of mitochondrial uncoupling, was not changed in mtDNA mutator and DM heart mitochondria indicating that mitochondrial dysfunction did not trigger a higher proton leak, regardless of the presence of UCP2. When either medium (octanoyl-carnitine) or long chain fatty acids (palmitoyl-carnitine) were used as substrates, OCR was higher in mtDNA mutator mitochondria (Figure 5D). In agreement with these results, we observed decreased maximal oxidation rates in DM animals, when a mixture of glutamate plus either fatty acid was provided as a substrate for energy production (Figure 5E). In contrast, mtDNA mutator mitochondria had unchanged maximal OCR (Figure 5E), suggesting that, by increasing mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, these animals can sustain normal energy production for prolonged periods and therefore postpone the onset of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

We describe a novel role of UCP2 in protection against early pathological changes in cardiomyocytes induced by respiratory deficiency due to increased mtDNA mutation load. Our results argue that this protective mechanism does not rely on the uncoupling activity of UCP2 leading to decreased ROS production in heart mitochondria. Instead, we show that UCP2 promotes fatty acid oxidation in heart, while also protecting from lactic acidosis resulting from systemic respiratory deficiency. This has an overall beneficial effect resulting in prolonged survival,delayed signs of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy and longer lifespan of mtDNA mutator mice.

Whether UCP2 plays a role in proton transport is still a matter of controversy. The increase in mitochondrial membrane potential in both macrophages and pancreatic β cells of UCP2 deficient mice is consistent with the proposed uncoupling activity [10], [34]. Besides, several lines of evidence showed that UCP2 decreases ROS production by lowering the membrane potential and therefore reducing reverse electron transfer into complex I [10], [34]. There are also strong arguments against the role of UCP2 in proton conductance. Unlike UCP1-deficient mice, UCP2 KO mice are resistant to cold exposure and they are not prone to obesity, even when fed a high fat diet, arguing against a role of UCP2 in energy expenditure [16]. Furthermore, depletion of UCP2 in tissues such as spleen or lung that express high levels of the protein does not change the uncoupling state of these cells [13]. In addition, a switch from fatty acid oxidation to glucose metabolism was demonstrated in UCP2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts [35], in agreement with our results.

Until very recently no UCP2 substrates were known and it was even proposed that UCP2, like UCP3, act as an outward transporter of long-chain fatty acid anions from the mitochondrial matrix in situations where the fatty acid delivery to mitochondria exceeds the oxidative capacity [36]. However, a recent study showed that UCP2 acts as a metabolite transporter that regulates substrate oxidation in mitochondria [37]. UCP2 seems to be involved in both glucose and glutamine metabolism by catalyzing the exchange of malate, oxaloacetate, aspartate and malonate for phosphate plus a proton from opposite sides of the membrane [37]. The higher levels of citric acid cycle intermediates found in the mitochondria of cells where Ucp2 is silenced, indicate that, by exporting C4 compounds out of mitochondria, UCP2 limits the oxidation of acetyl-CoA–producing substrates such as glucose and enhances glutaminolysis [37] Thus, UCP2 activity decreases the contribution of glucose to mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and promotes oxidation of alternative substrates such as glutamine and fatty acids [37].

We believe that UCP2 plays a role in stimulating lipid metabolism in mtDNA mutator cardiomyocytes. In combination with the observed general fasting-like phenotype that should promote increased lipolysis and availability of circulating fatty acids, this would allow better utilization of fatty acid oxidation while maintaining the energy-balance in conditions of moderate respiratory deficiency. As a result, high energy demanding tissues, such as heart, manage to produce enough energy, at least until fat stores are depleted. In the case of UCP2 deficiency, cells turn to glucose metabolism. However, respiratory deficiency makes the aerobic glycolysis inefficient, triggering a “vicious cycle” of metabolic events leading to diminishing efficiency of energy production, earlier development of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy and premature death. The increase in fatty acid delivery, in combination with defective fatty acid utilization, promotes lipid accumulation in the cardiomyocytes, which could additionally contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction in DM mice [38], [39]. Indeed, neurohumoral changes in heart failure, such as high adrenergic activity, can also increase the delivery of fatty acids to the heart by increasing lipolysis in adipose tissues [40]. Studies of substrate utilization in heart failure mostly show that fatty acid utilization is substantially decreased in advanced heart failure [41]. However, in contrast to patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and ischemic heart disease (IHD), patients with mitochondrial cardiomyopathy (MIC) have increased expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, including Ucp2, Cpt1, Pparα and Pgc1-α [23]. It was debated that this is a maladaptive mechanism leading to the worsening of phenotypes [23]. Indeed, it may seem paradoxical that in mitochondrial cardiomyopathy, fatty acid metabolism is upregulated. However, our results argue that higher level of fatty acid oxidation is actually beneficial for the respiratory-deficient heart that cannot use aerobic glycolysis to its fullest and therefore probably fails to provide enough energy to sustain cardiac function.

Lactic acidosis, as detected in DM mice, is a common symptom in patients with mitochondrial diseases and is largely postponed in mtDNA mutator mice as a consequence of UCP2 overexpression [42]. Aerobic glycolysis normally does not result in an increase in circulating lactate levels, since tissues including heart can use lactate as energy source when their respiratory chain is intact [42]. However, systemic lactic acidosis could cause further decline of mitochondrial function in tissues, as shown in Trans-mitochondrial mice carrying high levels of pathogenic mtDNA molecules [43]. Therefore, we propose that the observed further decline of cardiac mitochondrial function in DM mice is a result of both tissue autonomous (respiratory deficiency combined with lipotoxicity) and systemic (lactic acidosis) factors.

Our study provides further evidence that premature aging phenotypes and mitochondrial dysfunction caused by accumulation of random mtDNA mutations arise without increased ROS production, thus strengthening our view that mechanisms other than oxidative stress play an important role in this process. However, it is still possible that aberrant ROS signalling or altered redox status might play a role in the development of different phenotypes observed in mtDNA mutator mice. This was supported by results showing that both, neuronal stem cell and hematopoietic pluripotent cell defects could be ameliorated by N-acetyl cysteine treatment (NAC - a compound with antioxidant capacity and an effect on redox balance). Furthermore, although no evidence of increased oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids was ever found in the tissues or cells of mtDNA mutator mice [2], [44] their cardiomyopathy was attenuated by overexpression of mitochondrial-targeted catalase [45]. Hence, we believe that the interplay of mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS signaling is likely much more complex than we currently understand and mtDNA mutator is an invaluable model to dissect this even further. However, our results argue that UCP2 protein does not play a significant role in this process, or at least not in the highly energy demanding tissue such as heart.

Materials and Methods

Animals

UCP2-deficient mice and mtDNA mutator animals used in this study have been backcrossed for more than 20 generations to C57Bl6 background. To produce the double mutant (DM), PolgAmut/mut; Ucp2−/− animals, we initially crossed mice heterozygous for the mtDNA mutator allele (+/PolgAmut) with mice deficient in UCP2 (Ucp2−/−) [2], [34]. After a series of mating steps, we obtained UCP2-deficient mice that also carry one copy of the mtDNA mutator allele (+/PolgAmut; Ucp2−/−). These were then intercrossed to obtain UCP2 KO and DM mice. Wild type and mtDNA mutator mice were generated by intercrossing animals heterozygous for the mtDNA mutator allele [2]. Genotyping for both alleles was performed as described earlier [2], [34]. Mice were group-housed with food and water ad libitum and were maintained on a 12 h light-dark cycle. Animal protocols were in accordance with guidelines for humane treatment of animals and were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Stockholm region, Sweden and North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Food intake, glucose and lactate measurements

Daily food intake was calculated as the average intake of normal chow diet during 2 weeks. Mice were acclimated to the food intake settings for 5 days and were weighed every week to follow changes in body weight. Fed blood glucose and lactate concentrations were measured after tail-vein incision in 25-week-old animals, using glucose or lactate strips, which were read for absorbance in a reflectance meter (ACCU-CHEK AVIVA and Accutrend Plus, Roche Diagnostics GmBH, Mannheim, Germany).

Serum free fatty acids

Serum Non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) levels were determined using an acyl-CoA oxidase based colorimetric kit (WAKO NEFA–C; WAKO Wako Life Sciences, Inc., USA). NEFA standard solutions were used for the linear regression plot and absorbency measured at 550 nm in a Paradigm plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Western and northern blot analyses

Protein lysates were obtained by disrupting the tissue in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1 M NaF, 10 mM Na Orthovanadat, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM PMSF, 1 tablet protease inhibitor (Roche) in a tissue homogenizer (Precellys24, Bertin Technologies). After centrifugation, supernatants, containing solubilised proteins, were used for further analysis. Mitochondria were isolated from different tissues as previously described [46]. The antibodies and dilutions used for Western blot analyses are as follows: CALNEXIN (1∶2000, Calbiochem), Complex II 70 kDA Fp subunit (1∶1000, Molecular Probes), CPT1B (1∶1000, alpha Diagnostic), GLUT-1 (1∶1000, Abcam), GLUT-4 (1∶1000, Millipore), HSC-70 (1∶10000, Santa Cruz), MnSOD (1∶1000, Upstate Millipore), TOM20 (1∶1000, Santa Cruz), UCP3 (1∶1000, Abcam), UCP2 (1∶500, [12]), 4-HNE (1∶3000, Millipore). Oxyblots were performed according to the manufacturer instructions with 15–20 µg proteins (OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit, Millipore). Northern blot analyses were performed as described [47].

Measurement of Δp by radiolabeled probes distribution

Measurements were performed in respiration buffer containing 120 mM Sucrose, 50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris, 1 mM EGTA, 4 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2*6 H2O, 0.1% fatty acid free BSA, pH 7,2. Matrix space was determined by using 4.5 mCi [3H]H2O and 0.45 mCi inner membrane impermeable [14C]sucrose. ΔΨ and ΔpH were determined by the distribution of [3H]TPMP+ and [3H]acetate, respectively. [3H]TPMP+ is a lipophilic cation and its binding coefficient was determined as being equal to 0.38 [48]. Routinely, after equilibration, mitochondria were separated from the medium by rapid centrifugation (12000 g, 30 s), then treated as described previously [49].

Quantitative real-time PCR

Isolated RNA was treated with DNAse (DNA-free Kit, Ambion) and subsequently reversely transcribed with the High capacity reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Probes for target genes were from TaqMan Assay-on-Demand kits (Applied Biosystems) (Cat, Cpt1a, Cpt2, Fgf21, Glut4, Gpx, Hk1, Lpl, Sod1, Sod2, Txn1, Txn2, Ucp2). For other genes Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies) and primers as in Table S2 were used. Samples were adjusted for total RNA content by TATA box binding protein (Tbp) and Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt).

Enzyme histochemistry and respiratory chain function

Enzyme histochemical analyses of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and cytochrome c oxidase (COX) activities were performed on 14 µm cryostat sections of fresh frozen hearts [50]. The measurement of respiratory chain enzyme complex activities was performed as previously described [51].

Levels of serum hormones

Levels of hormones were quantified in serums of 30-week-old mice (diluted 1∶4) using Magnetic Bead Metabolic Assays (Bio-Plex, Bio-Rad, UK) and a Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transmission electron microscopy

Small pieces from the myocardium were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4 at room temperature and stored at 4°C. Specimens were rinsed in a PB and postfixed in 2% osmiumtetroxide in PB at 4°C for 2 h, dehydrated in ethanol followed by acetone and embedded in LX-112 (Ladd, Burlington, USA). Ultrathin sections (approximately 40–50 nm) were cut by a Leica ultracut (Leica, Wien, Austria). Sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate and examined in a Tecnai 10 transmission electron microscope (Fei Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 100 kV. Digital images were randomly taken by using a Veleta camera (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, GmbH, Münster, Germany) on myofibrils from sections of the myocardium.

Proton leak measurements

Mitochondria were isolated from heart tissue according to [46] and resuspended in MSE buffer (225 mM Mannitol, 75 mM Sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM HEPES) at a final concentration of 20 µg/ul. The mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed by fluorimetric detection of Rhodamine 123 fluorescence at a Shimadzu 5003PC spectrofluorimeter. Calibration curves to determine membrane potential from K+-diffusion potentials were performed with 140 µg Rhodamine 123 stained mitochondria treated with 1 µg/ml valinomycin, 2 µg/ml oligomycin and 100 nM rotenone in oxygen-saturated potassium-free buffer (10 mM Na H2PO4, 60 mM NaCl, 60 mM Tris/HCl, 110 mM Mannitol, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) containing 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate by titration with increasing KCl concentrations.

Measurement of membrane potential was conducted with 140 µg Rhodamine 123 stained mitochondria in air-saturated potassium-containing buffer (10 mM K H2PO4, 60 mM KCl, 60 mM Tris/HCl, 110 mM Mannitol, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) supplemented with 10 mM succinate by addition of increasing concentrations of malonate. Total uncoupling was assessed by addition of 1 µM TTFB. Oxygen consumption was analyzed under the conditions described for the determination of membrane potential in air-saturated potassium-containing buffer at 30°C in an Oroboros oxygraph.

Respiration measurements on fatty acids

The respiration measurements were performed on isolated heart mitochondria (as previously described) at 30°C using a high-resolution Oroboros-oxygraph in air-saturated medium consisting of 110 mM mannitol, 60 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mM Na2EDTA, and 60 mMTris – HCl (pH 7.4) containing either 5 mM malate, 2 mM ADP, 1 mM octanoyl carnitine or 5 mM malate, 2 mM ADP, 50 uM palmitoyl carnitine. The maximal oxidation rates in these conditions were analyzed by addition of 10 mM glutamate. The quality of mitochondria was assessed by incubation with 0.2 mM atractyloside.

Mitochondrial respiration and hydrogen peroxide production rate

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption flux was measured as previously described [52] at 37°C using 65–125 µg of crude mitochondria diluted in 2.1 ml of mitochondrial respiration buffer (120 mM sucrose, 50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 4 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.2) in an Oxygraph-2 k (OROBOROS INSTRUMENTS, Innsbruck, Austria). The oxygen consumption rate was measured using, either 10 mM pyruvate, 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate (PGM) or 10 mM succinate (S). Oxygen consumption was assessed in the phosphorylating state with 1 mM ADP (state 3) or non-phosphorylating state by adding 2.5 µg/ml oligomycin (pseudo state 4). In the control mitochondria, the respiratory control ratio (RCR) values were >8 with pyruvate/glutamate/malate. The rate of H2O2 production was determined by monitoring the oxidation of the fluorogenic indicator Amplex red (1 µM) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (5 U/ml). Fluorescence was recorded at the following wavelengths: excitation 560 nm and emission 590 nm. A standard curve was obtained by adding known amounts of H2O2 to the assay medium in the presence of the reactants. Mitochondria (65 µg protein/ml) were incubated in the respiratory medium at 37°C and the H2O2 production rate was initiated by adding either 10 mM pyruvate, 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate (PGM) or 10 mM succinate (S) or all substrates together (PGMS). Complex III inhibitor antimycin A was added (0.5 µM) after initial reading to further induce ROS production. The H2O2 production rate was determined from the slope of a plot of the fluorogenic indicator versus time.

ROS detection in MEFs

Primary MEFs (passage 1-3) were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with high glucose (4500 mg/L), 4 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg of streptomycin.

Cells (80-90% confluence) were washed by warm PBS, harvested by trypsinization and collected with complete culture medium by centrifugation (5 min at 200 g). After washing with PBS, cells were resuspended in 500 µl PBS, stained with 10 µmol/L of CM-H2DCFDA (5-(and-6-)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) and incubated in a cell incubator [(37°C), high relative humidity (95%), and controlled CO2 level (5%)] in the dark for 45 min. Propidium Iodide (1 µg/ml) was added to gate the living cells and tubes were kept on ice for immediate flow cytometry analysis. A total of 25000 events were analyzed and data expressed as Median + − SEM.

In vivo measurement of cardiac function

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed using a vertical Bruker AVANCEIII 9.4 Tesla Wide Bore NMR spectrometer equipped with an actively shielded 57-mm gradient set and a 30-mm birdcage resonator. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and kept at body temperature during the whole experiment. Acquisition and analysis of data were performed as described by Jacoby et al. [53].

Indirect calorimetry and physical activity

All measurements were performed in a PhenoMaster System (TSE systems, Bad Homburg, Germany), which allows measurement of metabolic performance and activity monitoring by an infrared light-beam frame. Mice were placed at room temperature (22°C–24°C) in 7.1-l chambers of the PhenoMaster open circuit calorimetry. Mice were allowed to acclimatize in the chambers for at least 24 hr. Locomotor activity and parameters of indirect calorimetry were measured for at least 48 hr. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

Glucose and insulin tolerance test

For the glucose tolerance test, animals were fasted for approximately 16 hours and blood glucose was measured immediately prior and 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes after the intraperitoneal injection of a glucose solution (2 g/kg body weight).

Insulin tolerance tests were performed on random fed animals between 2 : 00 and 5 : 00 PM. Animals were injected with 0.75 U/kg body weight of human insulin (Insuman Rapid 40 IU/ml) into the peritoneal cavity. Blood glucose values were measured immediately before and 15, 30, and 60 min after the injection. Results were expressed as percentage of initial blood glucose concentration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance for all figures was determined by Student's t-test. In addition we have analyzed all results with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Multiple Comparison. Results of ANOVA analyses are presented in Table S1.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HarmanD (1973) Free radical theory of aging. Triangle 12 : 153–158.

2. TrifunovicA, WredenbergA, FalkenbergM, SpelbrinkJN, RovioAT, et al. (2004) Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 429 : 417–423.

3. TrifunovicA, HanssonA, WredenbergA, RovioAT, DufourE, et al. (2005) Somatic mtDNA mutations cause aging phenotypes without affecting reactive oxygen species production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 17993–17998.

4. BrandMD (2000) Uncoupling to survive? The role of mitochondrial inefficiency in ageing. Exp Gerontol 35 : 811–820.

5. ShabalinaIG, NedergaardJ (2011) Mitochondrial (‘mild’) uncoupling and ROS production: physiologically relevant or not? Biochem Soc Trans 39 : 1305–1309.

6. RoussetS, Alves-GuerraMC, MozoJ, MirouxB, Cassard-DoulcierAM, et al. (2004) The biology of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Diabetes 53 Suppl 1S130–135.

7. CannonB, ShabalinaIG, KramarovaTV, PetrovicN, NedergaardJ (2006) Uncoupling proteins: a role in protection against reactive oxygen species—or not? Biochim Biophys Acta 1757 : 449–458.

8. BechmannI, DianoS, WardenCH, BartfaiT, NitschR, et al. (2002) Brain mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2): a protective stress signal in neuronal injury. Biochem Pharmacol 64 : 363–367.

9. FridellYW, Sanchez-BlancoA, SilviaBA, HelfandSL (2005) Targeted expression of the human uncoupling protein 2 (hUCP2) to adult neurons extends life span in the fly. Cell Metab 1 : 145–152.

10. ZhangCY, BaffyG, PerretP, KraussS, PeroniO, et al. (2001) Uncoupling protein-2 negatively regulates insulin secretion and is a major link between obesity, beta cell dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes. Cell 105 : 745–755.

11. ClaphamJC, ArchJR, ChapmanH, HaynesA, ListerC, et al. (2000) Mice overexpressing human uncoupling protein-3 in skeletal muscle are hyperphagic and lean. Nature 406 : 415–418.

12. PecqueurC, Alves-GuerraMC, GellyC, Levi-MeyrueisC, CouplanE, et al. (2001) Uncoupling protein 2, in vivo distribution, induction upon oxidative stress, and evidence for translational regulation. J Biol Chem 276 : 8705–8712.

13. CouplanE, del Mar Gonzalez-BarrosoM, Alves-GuerraMC, RicquierD, GoubernM, et al. (2002) No evidence for a basal, retinoic, or superoxide-induced uncoupling activity of the uncoupling protein 2 present in spleen or lung mitochondria. J Biol Chem 277 : 26268–26275.

14. AndrewsZB, HorvathTL (2009) Uncoupling protein-2 regulates lifespan in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E621–627.

15. DianoS, HorvathTL (2012) Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Mol Med 18 : 52–58.

16. PecqueurC, Alves-GuerraC, RicquierD, BouillaudF (2009) UCP2, a metabolic sensor coupling glucose oxidation to mitochondrial metabolism? IUBMB Life 61 : 762–767.

17. PiJ, BaiY, DanielKW, LiuD, LyghtO, et al. (2009) Persistent oxidative stress due to absence of uncoupling protein 2 associated with impaired pancreatic beta-cell function. Endocrinology 150 : 3040–3048.

18. AndrewsZB, LiuZW, WalllingfordN, ErionDM, BorokE, et al. (2008) UCP2 mediates ghrelin's action on NPY/AgRP neurons by lowering free radicals. Nature 454 : 846–851.

19. ChaudhriO, SmallC, BloomS (2006) Gastrointestinal hormones regulating appetite. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361 : 1187–1209.

20. SchwartzDR, LazarMA (2011) Human resistin: found in translation from mouse to man. Trends Endocrinol Metab 22 : 259–265.

21. BaggioLL, DruckerDJ (2007) Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 132 : 2131–2157.

22. De TaeyeB, SmithLH, VaughanDE (2005) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: a common denominator in obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 5 : 149–154.

23. SebastianiM, GiordanoC, NedianiC, TravagliniC, BorchiE, et al. (2007) Induction of mitochondrial biogenesis is a maladaptive mechanism in mitochondrial cardiomyopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol 50 : 1362–1369.

24. WangJ, WilhelmssonH, GraffC, LiH, OldforsA, et al. (1999) Dilated cardiomyopathy and atrioventricular conduction blocks induced by heart-specific inactivation of mitochondrial DNA gene expression. Nat Genet 21 : 133–137.

25. TyynismaaH, CarrollCJ, RaimundoN, Ahola-ErkkilaS, WenzT, et al. (2010) Mitochondrial myopathy induces a starvation-like response. Hum Mol Genet 19 : 3948–3958.

26. PlanavilaA, RedondoI, HondaresE, VinciguerraM, MuntsC, et al. (2013) Fibroblast growth factor 21 protects against cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Nat Commun 4 : 2019.

27. DoganSA, PujolC, MaitiP, KukatA, WangS, et al. (2014) Tissue-Specific Loss of DARS2 Activates Stress Responses Independently of Respiratory Chain Deficiency in the Heart. Cell Metab 19 : 458–469.

28. PotthoffMJ, KliewerSA, MangelsdorfDJ (2012) Endocrine fibroblast growth factors 15/19 and 21: from feast to famine. Genes Dev 26 : 312–324.

29. AhlqvistKJ, HamalainenRH, YatsugaS, UutelaM, TerziogluM, et al. (2012) Somatic progenitor cell vulnerability to mitochondrial DNA mutagenesis underlies progeroid phenotypes in Polg mutator mice. Cell Metab 15 : 100–109.

30. AbelED, DoenstT (2011) Mitochondrial adaptations to physiological vs. pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 90 : 234–242.

31. StorchJ, ThumserAE (2010) Tissue-specific functions in the fatty acid-binding protein family. J Biol Chem 285 : 32679–32683.

32. SchaapFG, van der VusseGJ, GlatzJF (1998) Fatty acid-binding proteins in the heart. Mol Cell Biochem 180 : 43–51.

33. SugdenMC, HolnessMJ (2003) Recent advances in mechanisms regulating glucose oxidation at the level of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by PDKs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E855–862.

34. ArsenijevicD, OnumaH, PecqueurC, RaimbaultS, ManningBS, et al. (2000) Disruption of the uncoupling protein-2 gene in mice reveals a role in immunity and reactive oxygen species production. Nat Genet 26 : 435–439.

35. PecqueurC, BuiT, GellyC, HauchardJ, BarbotC, et al. (2008) Uncoupling protein-2 controls proliferation by promoting fatty acid oxidation and limiting glycolysis-derived pyruvate utilization. FASEB J 22 : 9–18.

36. JezekP, EngstovaH, ZackovaM, VercesiAE, CostaAD, et al. (1998) Fatty acid cycling mechanism and mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1365 : 319–327.

37. VozzaA, ParisiG, De LeonardisF, LasorsaFM, CastegnaA, et al. (2014) UCP2 transports C4 metabolites out of mitochondria, regulating glucose and glutamine oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 : 960–965.

38. WendeAR, AbelED (2010) Lipotoxicity in the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801 : 311–319.

39. Abdul-GhaniMA, MullerFL, LiuY, ChavezAO, BalasB, et al. (2008) Deleterious action of FA metabolites on ATP synthesis: possible link between lipotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E678–685.

40. OpieLH, KnuutiJ (2009) The adrenergic-fatty acid load in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 54 : 1637–1646.

41. NeubauerS (2007) The failing heart—an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med 356 : 1140–1151.

42. DimauroS, MancusoM, NainiA (2004) Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies: therapeutic approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1011 : 232–245.

43. OgasawaraE, NakadaK, HayashiJ (2010) Lactic acidemia in the pathogenesis of mice carrying mitochondrial DNA with a deletion. Hum Mol Genet 19 : 3179–3189.

44. KujothGC, HionaA, PughTD, SomeyaS, PanzerK, et al. (2005) Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science 309 : 481–484.

45. DaiDF, ChenT, WanagatJ, LaflammeM, MarcinekDJ, et al. (2010) Age-dependent cardiomyopathy in mitochondrial mutator mice is attenuated by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Aging Cell 9 : 536–544.

46. ShabalinaIG, PetrovicN, KramarovaTV, HoeksJ, CannonB, et al. (2006) UCP1 and defense against oxidative stress. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal effects on brown fat mitochondria are uncoupling protein 1-independent. J Biol Chem 281 : 13882–13893.

47. SilvaJP, ShabalinaIG, DufourE, PetrovicN, BacklundEC, et al. (2005) SOD2 overexpression: enhanced mitochondrial tolerance but absence of effect on UCP activity. Embo J 24 : 4061–4070.

48. EspieP, GuerinB, RigouletM (1995) On isolated hepatocytes mitochondrial swelling induced in hypoosmotic medium does not affect the respiration rate. Biochim Biophys Acta 1230 : 139–146.

49. MourierA, DevinA, RigouletM (2009) Active proton leak in mitochondria: a new way to regulate substrate oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797 : 255–261.

50. SciaccoM, BonillaE (1996) Cytochemistry and immunocytochemistry of mitochondria in tissue sections. Methods Enzymol 264 : 509–521.

51. WibomR, HagenfeldtL, von DöbelnU (2002) Measurement of ATP production and respiratory chain enzyme activities in mitochondria isolated from small muscle biopsy samples. Anal Biochem 311 : 139–151.

52. MourierA, RuzzenenteB, BrandtT, KuhlbrandtW, LarssonNG (2014) Loss of LRPPRC causes ATP synthase deficiency. Hum Mol Genet 10 : 2580–2592.

53. JacobyC, MolojavyiA, FlogelU, MerxMW, DingZ, et al. (2006) Direct comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and conductance microcatheter in the evaluation of left ventricular function in mice. Basic Res Cardiol 101 : 87–95.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 6

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Inflammation: Gone with Translation

- Recombination Accelerates Adaptation on a Large-Scale Empirical Fitness Landscape in HIV-1

- Caspase Inhibition in Select Olfactory Neurons Restores Innate Attraction Behavior in Aged

- Accurate, Model-Based Tuning of Synthetic Gene Expression Using Introns in

- A Novel Peptidoglycan Binding Protein Crucial for PBP1A-Mediated Cell Wall Biogenesis in

- Ancient DNA Analysis of 8000 B.C. Near Eastern Farmers Supports an Early Neolithic Pioneer Maritime Colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands

- The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Critically Regulates Endometrial Function during Early Pregnancy

- Introgression from Domestic Goat Generated Variation at the Major Histocompatibility Complex of Alpine Ibex

- Netrins and Wnts Function Redundantly to Regulate Antero-Posterior and Dorso-Ventral Guidance in

- Coordination of Wing and Whole-Body Development at Developmental Milestones Ensures Robustness against Environmental and Physiological Perturbations

- Phenotypic Dissection of Bone Mineral Density Reveals Skeletal Site Specificity and Facilitates the Identification of Novel Loci in the Genetic Regulation of Bone Mass Attainment

- Deep Evolutionary Comparison of Gene Expression Identifies Parallel Recruitment of -Factors in Two Independent Origins of C Photosynthesis

- Loss of UCP2 Attenuates Mitochondrial Dysfunction without Altering ROS Production and Uncoupling Activity

- Translational Regulation of Specific mRNAs Controls Feedback Inhibition and Survival during Macrophage Activation

- Rosa26-GFP Direct Repeat (RaDR-GFP) Mice Reveal Tissue- and Age-Dependence of Homologous Recombination in Mammals

- Abnormal Type I Collagen Post-translational Modification and Crosslinking in a Cyclophilin B KO Mouse Model of Recessive Osteogenesis Imperfecta

- : Clonal Reinforcement Drives Evolution of a Simple Microbial Community

- Reviving the Dead: History and Reactivation of an Extinct L1

- Defective iA37 Modification of Mitochondrial and Cytosolic tRNAs Results from Pathogenic Mutations in TRIT1 and Its Substrate tRNA

- Early Back-to-Africa Migration into the Horn of Africa

- Aberrant Autolysosomal Regulation Is Linked to The Induction of Embryonic Senescence: Differential Roles of Beclin 1 and p53 in Vertebrate Spns1 Deficiency

- Microbial Succession in the Gut: Directional Trends of Taxonomic and Functional Change in a Birth Cohort of Spanish Infants

- Integrated Pathway-Based Approach Identifies Association between Genomic Regions at CTCF and CACNB2 and Schizophrenia

- Genetic Determinants of Long-Term Changes in Blood Lipid Concentrations: 10-Year Follow-Up of the GLACIER Study

- Palaeosymbiosis Revealed by Genomic Fossils of in a Strongyloidean Nematode

- Early Embryogenesis-Specific Expression of the Rice Transposon Enhances Amplification of the MITE

- PINK1-Mediated Phosphorylation of Parkin Boosts Parkin Activity in

- OsHUS1 Facilitates Accurate Meiotic Recombination in Rice

- Genetic Background Drives Transcriptional Variation in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

- Pervasive Divergence of Transcriptional Gene Regulation in Caenorhabditis Nematodes

- N-WASP Is Required for Structural Integrity of the Blood-Testis Barrier

- The Transcription Factor TFII-I Promotes DNA Translesion Synthesis and Genomic Stability

- An Operon of Three Transcriptional Regulators Controls Horizontal Gene Transfer of the Integrative and Conjugative Element ICE in B13

- Digital Genotyping of Macrosatellites and Multicopy Genes Reveals Novel Biological Functions Associated with Copy Number Variation of Large Tandem Repeats

- ATRA-Induced Cellular Differentiation and CD38 Expression Inhibits Acquisition of BCR-ABL Mutations for CML Acquired Resistance

- The EJC Binding and Dissociating Activity of PYM Is Regulated in

- JNK Controls the Onset of Mitosis in Planarian Stem Cells and Triggers Apoptotic Cell Death Required for Regeneration and Remodeling

- Mouse Y-Linked and Are Expressed during the Male-Specific Interphase between Meiosis I and Meiosis II and Promote the 2 Meiotic Division

- Rasa3 Controls Megakaryocyte Rap1 Activation, Integrin Signaling and Differentiation into Proplatelet

- Transcriptional Control of Steroid Biosynthesis Genes in the Prothoracic Gland by Ventral Veins Lacking and Knirps

- Souffle/Spastizin Controls Secretory Vesicle Maturation during Zebrafish Oogenesis

- The POU Factor Ventral Veins Lacking/Drifter Directs the Timing of Metamorphosis through Ecdysteroid and Juvenile Hormone Signaling

- The First Endogenous Herpesvirus, Identified in the Tarsier Genome, and Novel Sequences from Primate Rhadinoviruses and Lymphocryptoviruses

- Sequence of a Complete Chicken BG Haplotype Shows Dynamic Expansion and Contraction of Two Gene Lineages with Particular Expression Patterns

- Background Selection as Baseline for Nucleotide Variation across the Genome

- CPF-Associated Phosphatase Activity Opposes Condensin-Mediated Chromosome Condensation

- The Effects of Codon Context on Translation Speed

- Glycogen Synthase Kinase (GSK) 3β Phosphorylates and Protects Nuclear Myosin 1c from Proteasome-Mediated Degradation to Activate rDNA Transcription in Early G1 Cells

- Regulation of Gene Expression in Autoimmune Disease Loci and the Genetic Basis of Proliferation in CD4 Effector Memory T Cells

- Muscle Structure Influences Utrophin Expression in Mice

- BLMP-1/Blimp-1 Regulates the Spatiotemporal Cell Migration Pattern in

- Identification of Late Larval Stage Developmental Checkpoints in Regulated by Insulin/IGF and Steroid Hormone Signaling Pathways

- Transport of Magnesium by a Bacterial Nramp-Related Gene

- Sgo1 Regulates Both Condensin and Ipl1/Aurora B to Promote Chromosome Biorientation

- The HY5-PIF Regulatory Module Coordinates Light and Temperature Control of Photosynthetic Gene Transcription

- The Rim15-Endosulfine-PP2A Signalling Module Regulates Entry into Gametogenesis and Quiescence Distinct Mechanisms in Budding Yeast

- Regulation of Hfq by the RNA CrcZ in Carbon Catabolite Repression

- Loss of a Neural AMP-Activated Kinase Mimics the Effects of Elevated Serotonin on Fat, Movement, and Hormonal Secretions

- Positive Feedback of Expression Ensures Irreversible Meiotic Commitment in Budding Yeast

- Hecate/Grip2a Acts to Reorganize the Cytoskeleton in the Symmetry-Breaking Event of Embryonic Axis Induction

- Regulatory Mechanisms That Prevent Re-initiation of DNA Replication Can Be Locally Modulated at Origins by Nearby Sequence Elements

- Speciation and Introgression between and

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Early Back-to-Africa Migration into the Horn of Africa

- PINK1-Mediated Phosphorylation of Parkin Boosts Parkin Activity in

- OsHUS1 Facilitates Accurate Meiotic Recombination in Rice

- An Operon of Three Transcriptional Regulators Controls Horizontal Gene Transfer of the Integrative and Conjugative Element ICE in B13

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání