-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Scale of Population Structure in

The population structure of an organism reflects its evolutionary history and influences its evolutionary trajectory. It constrains the combination of genetic diversity and reveals patterns of past gene flow. Understanding it is a prerequisite for detecting genomic regions under selection, predicting the effect of population disturbances, or modeling gene flow. This paper examines the detailed global population structure of Arabidopsis thaliana. Using a set of 5,707 plants collected from around the globe and genotyped at 149 SNPs, we show that while A. thaliana as a species self-fertilizes 97% of the time, there is considerable variation among local groups. This level of outcrossing greatly limits observed heterozygosity but is sufficient to generate considerable local haplotypic diversity. We also find that in its native Eurasian range A. thaliana exhibits continuous isolation by distance at every geographic scale without natural breaks corresponding to classical notions of populations. By contrast, in North America, where it exists as an exotic species, A. thaliana exhibits little or no population structure at a continental scale but local isolation by distance that extends hundreds of km. This suggests a pattern for the development of isolation by distance that can establish itself shortly after an organism fills a new habitat range. It also raises questions about the general applicability of many standard population genetics models. Any model based on discrete clusters of interchangeable individuals will be an uneasy fit to organisms like A. thaliana which exhibit continuous isolation by distance on many scales.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000843

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000843Summary

The population structure of an organism reflects its evolutionary history and influences its evolutionary trajectory. It constrains the combination of genetic diversity and reveals patterns of past gene flow. Understanding it is a prerequisite for detecting genomic regions under selection, predicting the effect of population disturbances, or modeling gene flow. This paper examines the detailed global population structure of Arabidopsis thaliana. Using a set of 5,707 plants collected from around the globe and genotyped at 149 SNPs, we show that while A. thaliana as a species self-fertilizes 97% of the time, there is considerable variation among local groups. This level of outcrossing greatly limits observed heterozygosity but is sufficient to generate considerable local haplotypic diversity. We also find that in its native Eurasian range A. thaliana exhibits continuous isolation by distance at every geographic scale without natural breaks corresponding to classical notions of populations. By contrast, in North America, where it exists as an exotic species, A. thaliana exhibits little or no population structure at a continental scale but local isolation by distance that extends hundreds of km. This suggests a pattern for the development of isolation by distance that can establish itself shortly after an organism fills a new habitat range. It also raises questions about the general applicability of many standard population genetics models. Any model based on discrete clusters of interchangeable individuals will be an uneasy fit to organisms like A. thaliana which exhibit continuous isolation by distance on many scales.

Introduction

When studying natural populations, reasonable models of isolation, migration, and population growth should be applied to estimate the population structure of an organism [1]. Furthermore, it is also important to understand the way in which a species' population structure has been altered by anthropogenic disturbance. The population structure of domesticated organisms such as corn or rice are clearly drastically influenced by human intervention and provide extreme examples of how demographic processes can influence the genetic diversity and distribution of a species [2]–[6]. There are now few organisms whose habitat range does not coincide with human activity or for whom interference in their population structure is of little concern. The degree of impact humans have - be it on purpose or not - on the population structures of species that are not targets of domestication is unclear.

In this paper we present the results of a large scale study of the global population of Arabidopsis thaliana as an example of a natural organism that, like many others, exists in a predominantly continuous habitat that is much larger than the migration range of any individual, engages in sexual reproduction (with at least some regularity), and exists partially as a human commensal but serves no agricultural purpose.

Results

Composition of Sample

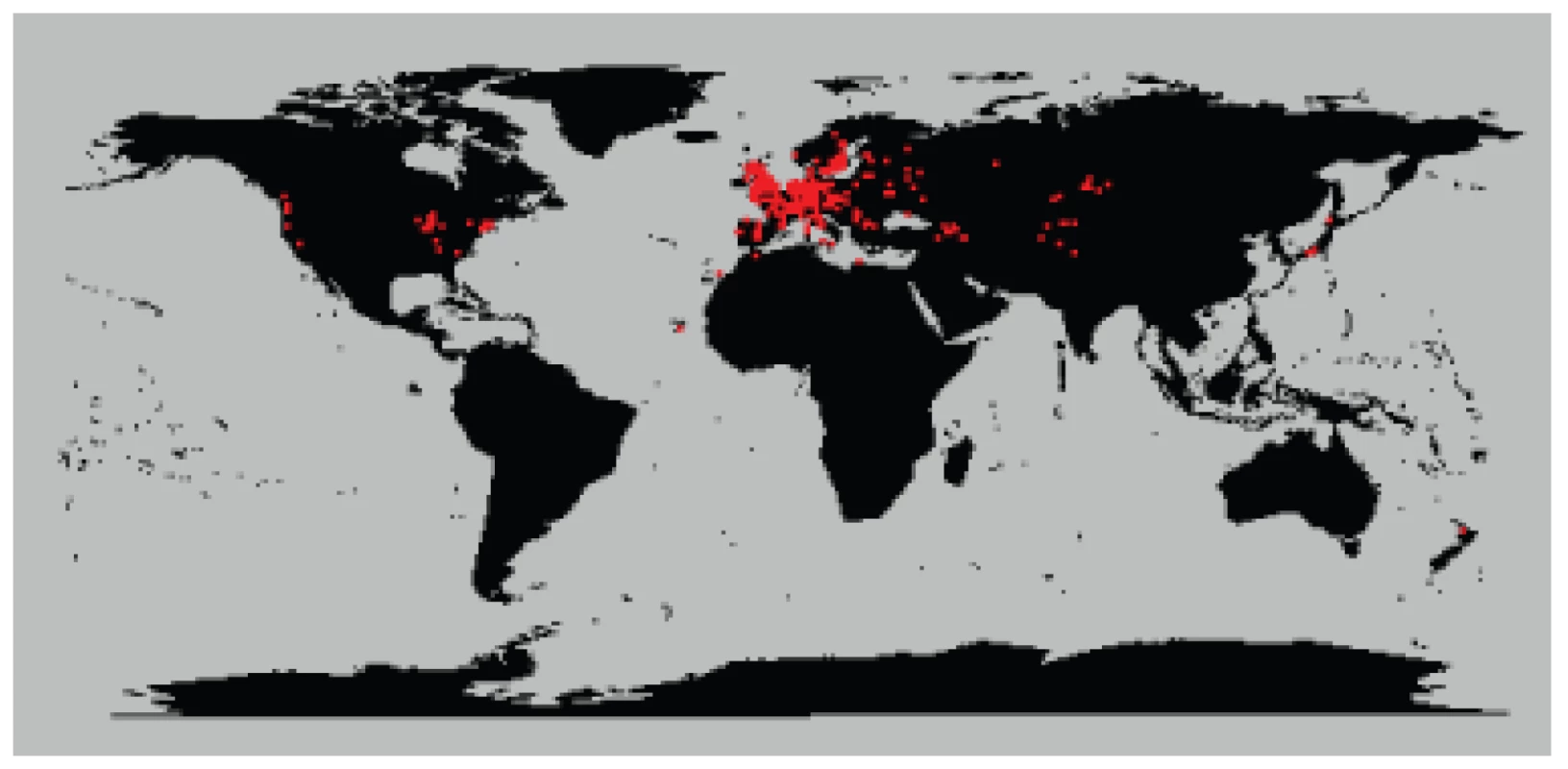

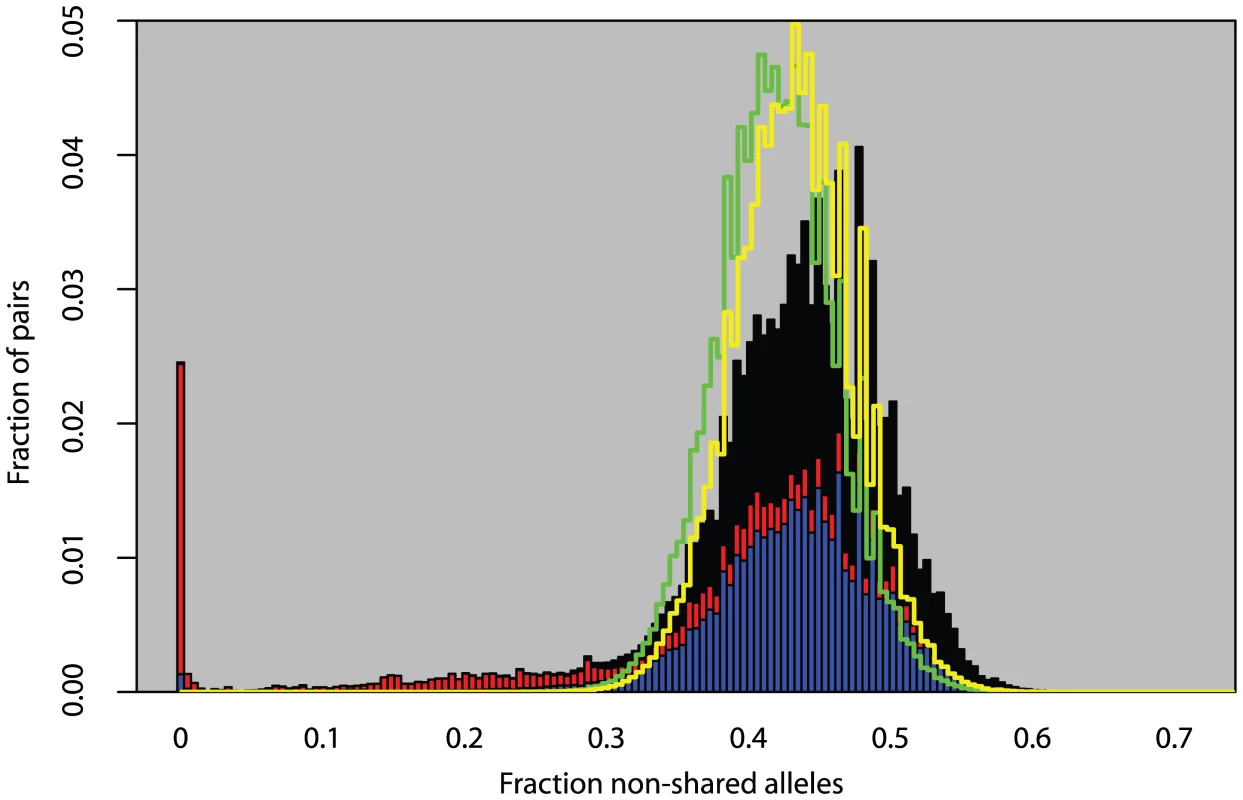

We analyzed 5,707 plants collected around the globe (Figure 1) with 139 SNPs spread across the genome. These plants cluster into 1,799 different haplogroups with approximately three quarters of those haplogroups consisting of a single unique plant. Some haplogroups are represented by tens, or even hundreds, of individuals (Figures S1, S2, S3). One haplogroup was found over a thousand times across North America and another was found more than 200 times across the United Kingdom. Looking at the distribution of all pairwise genetic distances highlights three types of inter-plant relationships: they can be genetically identical (approximately 3% of all pairs in the sample, mostly pairs within North America), they can be completely unrelated plants given our marker resolution (approximately 85% of pairs in the sample, mostly inter-continental pairs or pairs within Eurasia), or they can show an intermediate degree of relatedness to each other (approximately 12% of pairs in the sample, mostly pairs with North America with very few inter-continental pairs) (Figure 2). Simulations demonstrate that these intermediate relations cannot be explained in a panmictic population and are therefore consistent with a more structured population.

Fig. 1. Map of collection sites around the world.

Red dots indicate sample sites. Fig. 2. Fraction of non-matching alleles between all pairs of plants.

Solid bars are observed measurements from data. Stacked on each other are pairs within Eurasia (blue), pairs within North America (red), and inter-continental pairs (black). Green line is the distribution from a simulation assuming panmixia. Yellow line is a simulation assuming global random mating but only measuring differences between unique haplotypes. Heterozygosity and Outcrossing

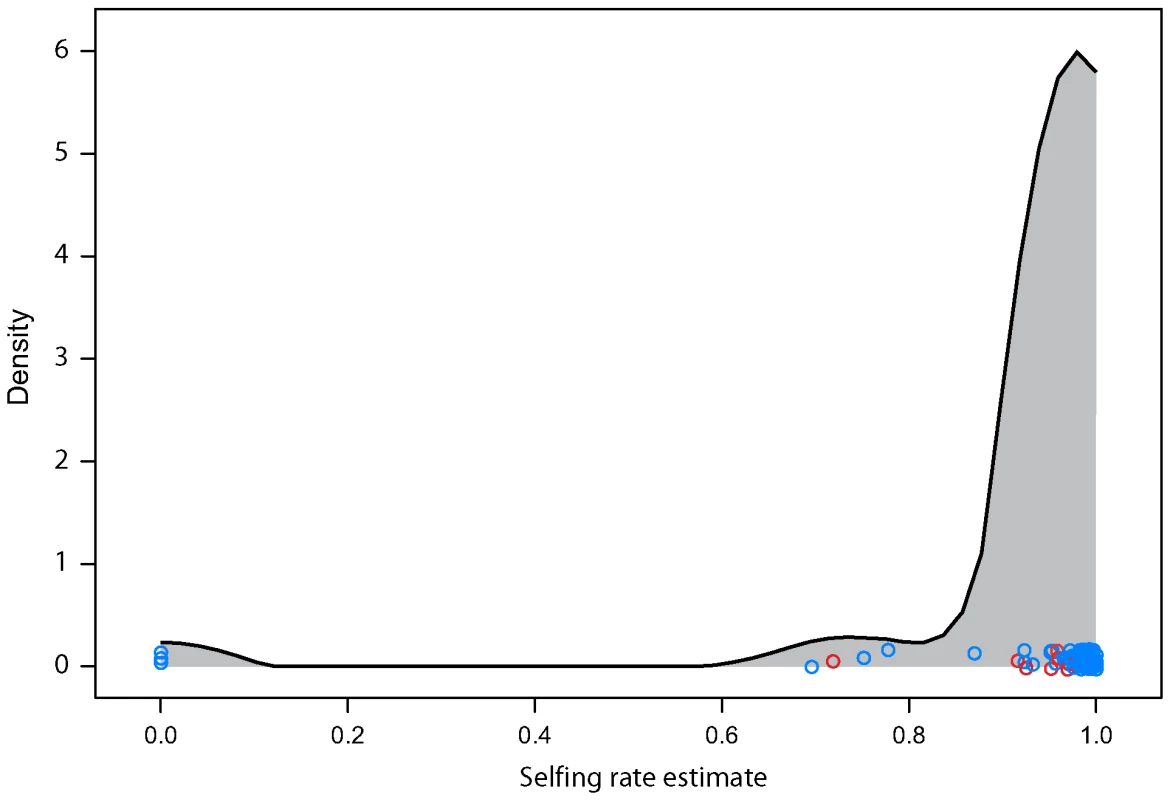

Arabidopsis thaliana frequently reproduces by self-fertilizing and only occasionally outcrosses. The level of heterozygosity in the sample is therefore quite low compared to most organisms that obligately outcross. With self-fertilization and bi-parental inbreeding, we find that 95% of plants having five or fewer heterozygous loci. We estimated outcrossing rate in each field site from the distribution of number of heterozygous markers in each individual. As a whole our sample selfed 97% of the time overall in its recent history with the middle 50% of sites having estimates ranging from 95% to 99%. The estimates were lower in North American sites (Wilcoxon test p-value<0.005) which had an average of a 92% selfing rate and range of the middle 50% from 92% to 96% (Figure 3). Three sites had 0% selfing as their maximum likelihood estimates. These sites included 2, 3, and 5 plants (respectively). While the estimates are robust across loci (bootstrapping gives upper 95% confidence intervals of no more than 10% selfing for any of these sites), the small sample sizes may not be representative of the site as a whole. Most of the material used for this analysis was taken from seeds collected in the field or from mature plants grown under lab conditions from field-collected seed. As such there was a reduced chance for natural selection to influence the heterozygosity of the sample as it may have done had the seeds been allowed to grow to maturity under natural conditions. If inbreeding depression plays a significant role in A. thaliana [7],[8] the heterozygosity of a cohort of mature plants would be expected to be higher than the seed population from which it grows. Under these circumstances the effective selfing rate, the contribution to future gene pools from self-fertilized plants, could be somewhat lower than we estimate here. Differences in sample tissue composition between North American and Eurasian samples may contribute to the difference in estimated selfing rate between the continents.

Fig. 3. Estimated selfing rate per field site.

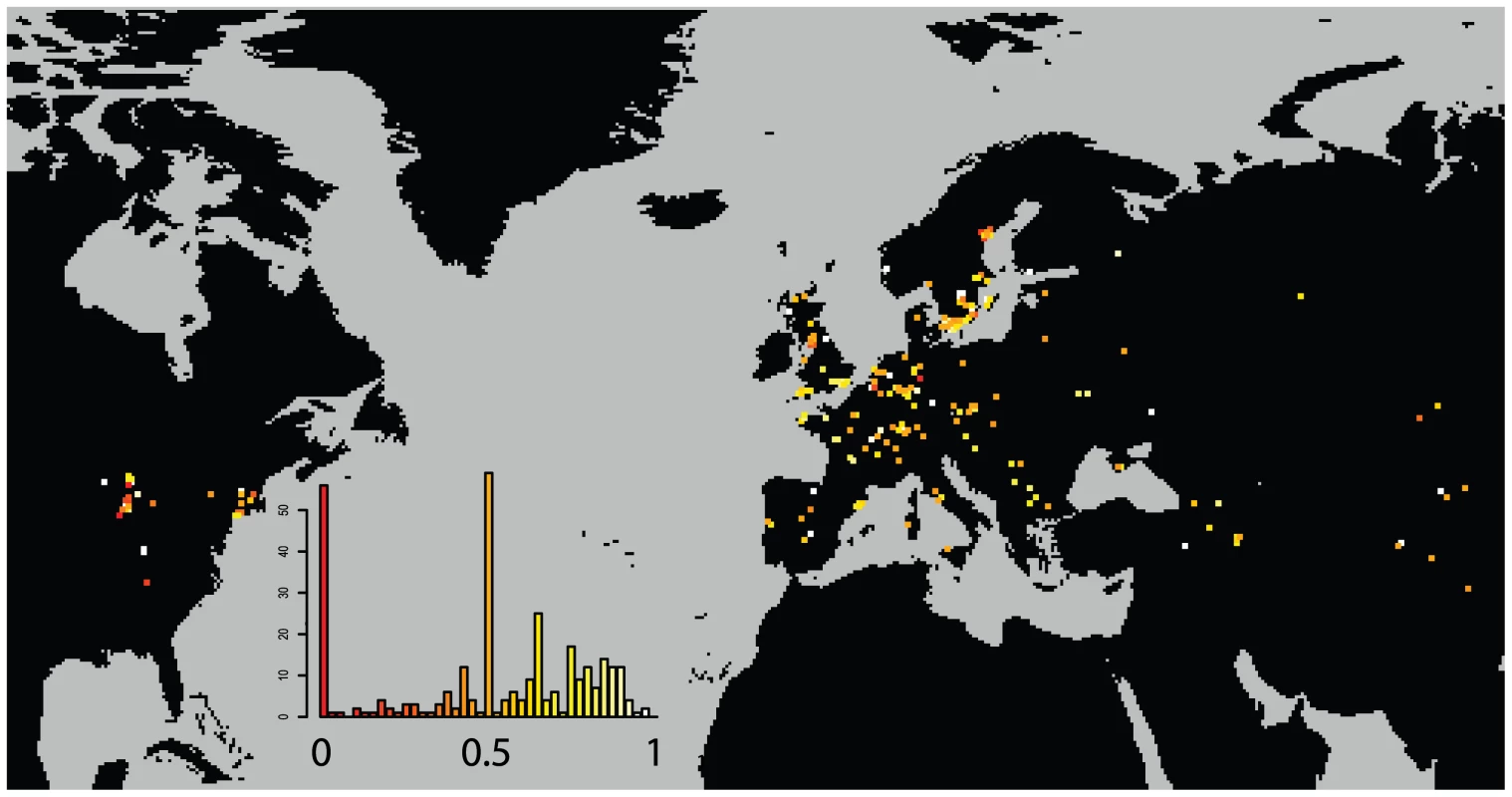

Individual dots are specific field sites. North American sites are in red. The curve is a smoothed kernel density. While this level of selfing is high enough to greatly depress the individual heterozygosity of the sample, it is low enough to thoroughly mix haplotypes whenever two distinct haplotypes find themselves in close proximity. (Figure 4) shows the probability that two plants drawn from a given site are from a different haplogroup. Approximately 1/5th of sites are dominated by a single haplogroup (>80%). This includes nearly half the sites in North America but only 1/8th of Eurasian sites. The polymorphic field sites, however, are often quite variable and comprised of plants with unique haplotypes.

Fig. 4. Distribution of haplogroup diversity by field site.

Probability of two plants in a field site being of different haplogroups. Low values (red) indicate monomorphic field sites. High values (light) indicate diverse field sites. A dynamic map will be available online at (http://arabidopsis.usc.edu/Accession/). Isolation by Distance

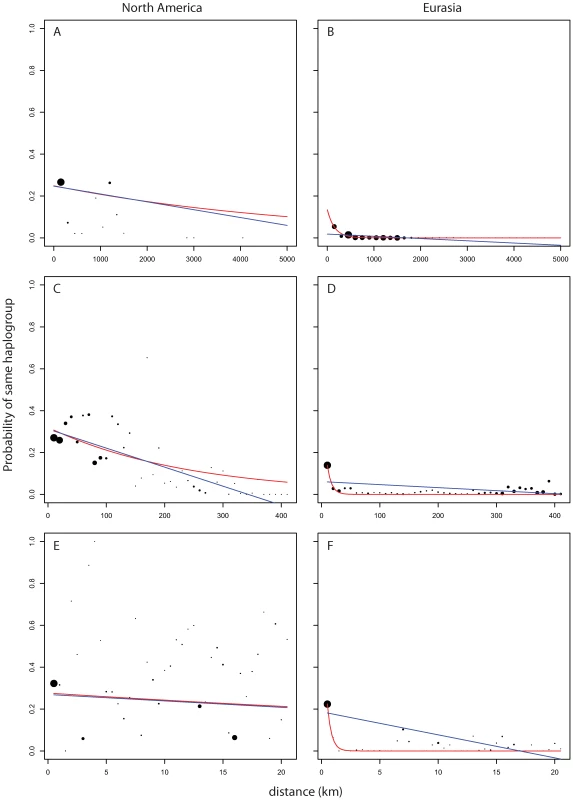

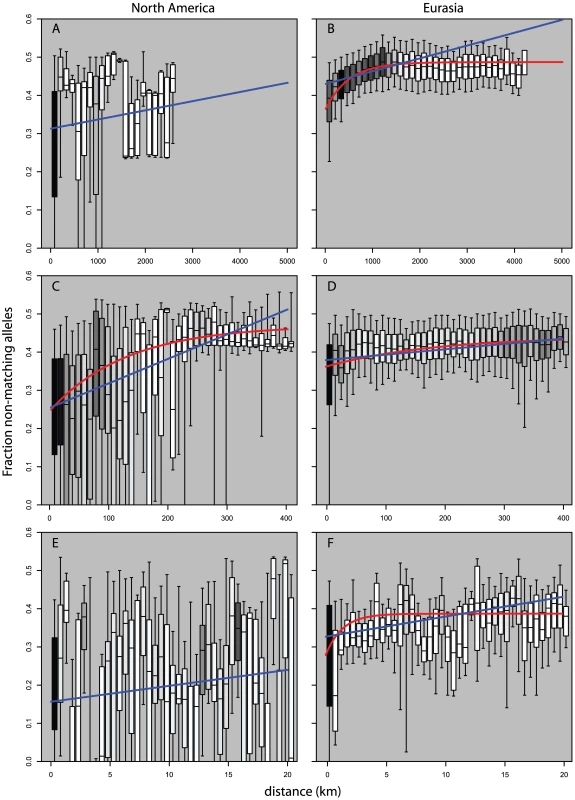

Looking at measures of similarities between pairs of plants as a function of geographic distance we see striking differences in pattern between pairs of Eurasian plants and pairs of North American plants. Figure 5B and Figure 6B show the strong broad trend of decay of genetic similarity with increasing geographic distance across Eurasia. The fraction of differing alleles rises to saturation across the continent and the probability of finding two plants of the same haplogroup becomes negligible beyond 1000 km. Panels A, showing effects of similar scale in North America, show extremely wide-spread haplogroups and little relation between distance and allelic similarity. The entire negative slope of Figure 6A can be explained by the distribution of haplogroups in Figure 5A. Figure 5C and Figure 5D are the same data on a smaller geographic scale. Figure 5D is similar to Figure 5B and show that Eurasia's isolation by distance continues in a smooth manner at this level of resolution. Figure 5C reveals that North American Arabidopsis thaliana does exhibit a measure of isolation by distance at this smaller scale though with a great deal more noise than in Eurasia. Figure 5E and 5F continue this trend at a very fine scale. Both continents exhibit isolation by distance at this level though the pattern is more pronounced in Eurasia.

Fig. 5. Probability of finding two members of a haplogroup as a function of distance and continent.

Dot size shows relative (within panel) number of observations per bin. Blue line is curve of the form y = mx+b that is best fit to the binned data. Red line is model of exponential decay of the form y = Cexp(−λ*x) that is best fit to the binned data. (A,B) use 150 km bins. (C,D) use 10 km bins. (E,F) use 1/2 km bins. Fig. 6. Pairwise distribution of non-shared alleles as a function of geographic distance and continent.

Boxes show median, 25th and 75th percentile; whiskers show 9th and 91st percentile. Shading shows relative (within panel) number of observations per bin. Blue line is curve of the form y = mx+b that is best fit to the binned data. Red line is model of exponential decay of the form y = K-Cexp(−λ*x) that is best fit to the binned data. (A,B) use 150 km bins. (C,D) use 10 km bins. (E,F) use 1/2 km bins. Data in (A,E) would not converge on an exponential curve. Discussion

When a species has established itself across a broad geographic range, migrates relatively slowly, and outcrosses with reasonable frequency, isolation by distance is an inevitable outcome. Every time a new haplotype migrates to a nearby area it recombines with the local haplotypes creating organisms of intermediate relatedness. Occasional long-distance migration events may have only weak effects on this continuum, as crossing and back-crossing with local haplotypes would dilute the impact. Aggressively invading haplotypes and selective sweeps can, however, strongly disrupt this process. Both can allow individual haplotypes to spread over much greater distances before being broken apart by the locally established haplotype pools. This is consistent with the pattern that has previously been identified in smaller studies of Arabidopsis thaliana within regions of Europe and Asia [9],[10].

A species newly introduced to a region is expected to have a different pattern. As the species spreads across its new range its migration events bring it to previously unoccupied areas. Without established local haplotypes there is no recombination, no intermediate genotypes are formed, and single, un-recombined haplotypes can spread uninterrupted over great distances. As the new range becomes filled with the species, however, isolation by distance will begin to establish itself, first on very local scales and gradually spreading out as recombination creates geographically unique haplotypes and migration and recombination between occupied areas blends them together. These patterns are consistent with our observations. In Eurasia, where Arabidopsis thaliana has flourished for thousands of years, it has established a strong gradient of isolation by distance. In North America, which has been colonized in the last three hundred years [11], haplotypes are spread across the entire continent but weak isolation by distance is emerging, particularly over shorter distances.

Arabidopsis thaliana is often a human commensal in both North America and Eurasia. The largest difference between its natural history on the two continents is that it has existed across Eurasia for thousands of years and in North America for only a couple of centuries. Human disturbance does not appear to have radically altered its natural population structure in Eurasia and the results suggest that the disturbance in North America is transitory and that a natural form of isolation by distance will emerge over time. This suggests that for organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana human disturbance only has a particularly large effect on population structure when established local populations are small or absent, or when an entire local gene-pool is replaced by artificial migrants. Otherwise, even moderate human disturbance can be swamped out by natural processes.

This kind of continuous isolation by distance is a type of population structure that the field of population genetics is poorly equipped to deal with. While there are several exceptions [12]–[16], most of population genetics theory is premised on the existence of discrete populations of exchangeable individuals. Even the modern field of landscape genetics [17]–[18] is focused on finding discrete regions within continuous habitats that behave like classic populations. Organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana, however, do not fit such models. With continuous geographic variation the probability of observing a particular set of alleles in an organism depends on the unique location of that organism and the alleles at the next closest organism are expected to have been drawn from a slightly different distribution. Sufficiently fine-scaled lattices of stepping-stone models may approximate many of the important features of this kind of structure, but it is not straightforward to determine the appropriate scale and having too coarse a scale may quickly degrade the numerical results (particularly for populations not at equilibrium) [19]. Hierarchical models are particularly inappropriate. The migration rate is low compared to the outcrossing rate, which very quickly (on a scale generally less than a kilometer) creates a geographic blend of alleles and extremely rich pools of local haplotypes. There is no bifurcating process to be uncovered (Figure S4, Figure S5, Text S1). To accurately estimate effective population size, gene flow, recombination, and natural selection in populations exhibiting continuous variation it will be necessary to reexamine the often over-looked theory of spatial genetics and develop new methods. A recent review of the subject [20] suggests several promising approaches.

For researchers using Arabidopsis thaliana as a model organism for ecological and evolutionary studies this paper provides several lessons and raises several new questions. One important point is that it is necessary to recognize that both genotype and environment are expected to vary spatially. Any study of local adaptation or gene by environment interaction should expect to find correlations between genotypes and environments simply through spatial correlation. Study design and analysis must take this into account and show that similarities between plants separated by a given distance within environments are greater than those at similar distances but between environments. Another point is that in terms of genetic diversity, Arabidopsis thaliana needs to be thought of as a sexually reproducing species: the difference between outcrossing and highly selfing organisms is quantitative rather than qualitative. Each plant in the wild may contain multiple hybrid siliques. While the vast majority of individual seeds are self-fertilized, the outcrossing rate is sufficient to introduce considerable genetic recombination after just a few generations. This will help make natural samples of Arabidopsis thaliana a powerful research subject for genome-wide association studies and linkage mapping [21], but create difficulties in reconstructing even fairly recent phylogeographic events such as the colonization of North America (let alone older events such as the re-colonization of Eurasia after the most recent ice age). Future studies using higher-density marker sets will have considerably more power to address these questions.

Methods

Collection

The collection is described in detail at http://arabidopsis.usc.edu/Accession/. It contains 4756 new accessions and 1201 accessions obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) as a leaf from a single reference plant such that the distributed seed matches the genotype in this study. The collection spans 42 countries and four continents.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated using Puregene 96-well DNA purification kit (Gentra Systems) with the modified protocol [22]. All DNA samples were normalized to 10 ng/ul, and then genotyped using The Sequenom MassArray (compact) system at Sequenom (San Diego, CA) and University of Chicago DNA sequencing facility (Chicago, IL) with 149 SNPs. The primer sequences of the 149 SNPs and their physical and relative genetic distances are listed on the web (http://borevitzlab.uchicago.edu/resources/molecular-resources/snp-markers). They were selected from loci exhibiting minor allele frequencies between 25 and 30% in a set of globally-distributed DNA alignments [23] using MSQT [24].

Data Cleaning

Samples were removed if they contained excess missing genotype calls (>50 of 149) as this indicates poor quality of the genomic DNA or contamination. Information from ten SNP assays was removed due to excess missing genotypes or heterozygous calls (>25% of sample) which is often an indicator of poorly performing genotype assays. Haplogroups containing common lab strains Col, Ler, Ws2, and Nd were also removed to limit the chances of contamination. Multiple samples of each were found and at suspiciously broad global distributions.

Haplogroup Clustering

Each plant was assigned to a single unique haplogroup. All plants in a haplogroup have haplotypes that are potentially identical given the number of SNPs genotyped and the accuracy of the SNP genotyping. Clusters are defined by a modified QT-clustering [25] algorithm. The distance function between two haplotypes is derived from the binomial probability of finding the observed number or more of marker mismatches between them given the number of observed markers. The first haplogroup is defined by finding the central haplotype around which it is possible to form the largest haplogroup. Haplotypes are proposed in order of their distance from the central haplotype and are included if their distance is less than 0.05 times the current size of the cluster. Once the largest haplogroup is defined it is removed from the sample and the next largest haplogroup is defined. This is iterated until every plant has been placed in a haplogroup. Heterozygous markers were treated as missing data.

Diversity Simulations

To simulate the distribution of pairwise fraction of non-matching alleles we simulated a sample of 10,000 haplotypes. For each marker in each haplotype an allele was taken from the corresponding site of an observed haplotype randomly chosen with replacement. The simulation adjusted for production of identical haplogroups was done in the same manner, however only one representative of each haplogroup was included in the random sampling.

Estimation of Selfing Rates

Selfing rates were estimated for 88 field sites with 8 from North America. These are all the sites for which the genotyped tissues were from plants that were from plants grown from field-collected seed (1820) or mature field-grown plants (219, all from North America) and for which there were at least two haplogroups present. Estimates were derived from the inbreeding coefficient FIS[26] in each field site as implemented in [27] http://lewis.eeb.uconn.edu/lewishome/software.html. The selfing rate is calculated as 2/(1/FIS+1). This relationship between FIS and the selfing rate assumes that outcrossing occurs uniformly across individuals within field sites and that the populations have reached equilibrium with respect to allele frequencies and heterozygosity. To the extent that mating is structured by within-field site geography our estimates will be slightly inflated from the true values.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KlimanRM

AndolfattoP

CoyneJA

DepaulisF

KreitmanM

2000 The Population Genetics of the Origin and Divergence of the Drosophila simulans Complex Species. Genetics 156 1913 1931

2. MarchiniJ

CardonLR

PhillipsMS

DonnellyP

2004 The effects of human population structure on large genetic association studies. Nat Genet 36 512 517 doi:10.1038/ng1337

3. VoightBF

PritchardJK

2005 Confounding from cryptic relatedness in case-control association studies. PLoS Genet 1 e32 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010032

4. BucklerES

ThornsberryJM

KresovichS

2001 Molecular Diversity, Structure and Domestication of Grasses. Genetics Research 77 213 218 doi:10.1017/S0016672301005158

5. SasakiT

MatsumotoT

YamamotoK

SakataK

BabaT

2002 The genome sequence and structure of rice chromosome 1. Nature 420 312 316 doi:10.1038/nature01184

6. RafalskiA

MorganteM

2004 Corn and humans: recombination and linkage disequilibrium in two genomes of similar size. Trends in Genetics 20 103 111 doi:10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.002

7. Mitchell-OldsT

1995 Interval Mapping of Viability Loci Causing Heterosis in Arabidopsis. Genetics 140 1105 1109

8. BustamanteCD

NielsenR

SawyerSA

OlsenKM

PuruggananMD

2002 The cost of inbreeding in Arabidopsis. Nature 416 531 534 doi:10.1038/416531a

9. BeckJB

SchmuthsHeike

SchaalBarbaraA.

2008 Native range genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana is strongly geographically structured and reflects Pleistocene glacial dynamics. Molecular Ecology 17 902 915 doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03615.x

10. PicoFX

Mendez-VigoB

Martínez-ZapaterJM

Alonso-BlancoC

2008 Natural Genetic Variation of Arabidopsis thaliana Is Geographically Structured in the Iberian Peninsula. Genetics 180 1009 1021 doi:10.1534/genetics.108.089581

11. O'KaneSL

Al-ShehbazIA

1997 A Synopsis of Arabidopsis (Brassicaceae). Novon 7 323 327 doi:10.2307/3391949

12. WrightS

1943 Isolation by Distance. Genetics 28 114 138

13. MaruyamaT

1972 Rate of Decrease of Genetic Variability in a Two-Dimensional Continuous Population of Finite Size. Genetics 70 639 651

14. BartonNH

WilsonI

1995 Genealogies and Geography. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 349 49 59 doi:10.2307/56123

15. WilkinsJF

2004 A Separation-of-Timescales Approach to the Coalescent in a Continuous Population. Genetics 168 2227 2244 doi:10.1534/genetics.103.022830

16. KnowlesLL

CarstensBC

2007 Estimating a geographically explicit model of population divergence. Evolution 61(3) 477 493

17. GuillotG

EstoupA

MortierF

CossonJF

2005 A Spatial Statistical Model for Landscape Genetics. Genetics 170 1261 1280 doi:10.1534/genetics.104.033803

18. StorferA

MurphyMA

EvansJS

GoldbergCS

RobinsonS

2006 Putting the /‘landscape/’ in landscape genetics. Heredity 98 128 142

19. WilkinsJF

MarloweFW

2006 Sex-biased migration in humans: what should we expect from genetic data? BioEssays 28 290 300 doi:10.1002/bies.20378

20. GuillotG

LebloisR

CoulonA

FrantzAC

2009 Statistical methods in spatial genetics. Molecular Ecology 18 4734 4756 doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04410.x

21. AtwellS

Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in a common set of Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature. in press

22. LiY

2007 Purification of Arabidopsis DNA in 96-Well Plate Using the PUREGENE DNA Purification Kit. p87.

WeinerMP

GabrielS

StephensJC

Genetic variation: a laboratory manual In book: Cold Spring harbor laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York

23. NordborgM

HuTT

IshinoY

JhaveriJ

ToomajianC

2005 The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol 3 e196 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030196

24. WarthmannN

FitzJ

WeigelD

2007 MSQT for choosing SNP assays from multiple DNA alignments. Bioinformatics 23 2784 2787 doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm428

25. HeyerLJ

KruglyakS

YoosephS

1999 Exploring Expression Data: Identification and Analysis of Coexpressed Genes. Genome Res 9 1106 1115

26. WeirBS

CockerhamCC

1984 Estimating F-Statistics for the Analysis of Population Structure. Evolution 38 1358 1370

27. LewisP

ZaykinD

2001 Genetic Data Analysis: Computer program for the analysis of allelic data Version 1.0 (d16c).

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the GenomeČlánek Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in MiceČlánek Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' DiseaseČlánek Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD TagsČlánek Wing Patterns in the Mist

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 2

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Scale of Population Structure in

- Allelic Exchange of Pheromones and Their Receptors Reprograms Sexual Identity in

- Genetic and Functional Dissection of and in Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- A Single Nucleotide Polymorphism within the Acetyl-Coenzyme A Carboxylase Beta Gene Is Associated with Proteinuria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling

- Genome-Wide Association Study in Asian Populations Identifies Variants in and Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Cdk2 Is Required for p53-Independent G/M Checkpoint Control

- Uncoupling of Satellite DNA and Centromeric Function in the Genus

- Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in the Clade

- Use of DNA–Damaging Agents and RNA Pooling to Assess Expression Profiles Associated with and Mutation Status in Familial Breast Cancer Patients

- Cheating by Exploitation of Developmental Prestalk Patterning in

- Replication and Active Demethylation Represent Partially Overlapping Mechanisms for Erasure of H3K4me3 in Budding Yeast

- Cdk1 Targets Srs2 to Complete Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing and to Promote Recombinational Repair

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Susceptibility Variants for Type 2 Diabetes in Han Chinese

- Genome-Wide Identification of Susceptibility Alleles for Viral Infections through a Population Genetics Approach

- Transcriptional Rewiring of the Sex Determining Gene Duplicate by Transposable Elements

- Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in

- Proteasome Nuclear Activity Affects Chromosome Stability by Controlling the Turnover of Mms22, a Protein Important for DNA Repair

- Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in Mice

- Structure, Function, and Evolution of the spp. Genome

- Human and Non-Human Primate Genomes Share Hotspots of Positive Selection

- A Kinase-Independent Role for the Rad3-Rad26 Complex in Recruitment of Tel1 to Telomeres in Fission Yeast

- Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' Disease

- Molecular Evolution and Functional Characterization of Insulin-Like Peptides

- Molecular Poltergeists: Mitochondrial DNA Copies () in Sequenced Nuclear Genomes

- Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD Tags

- Wing Patterns in the Mist

- DNA Binding of Centromere Protein C (CENPC) Is Stabilized by Single-Stranded RNA

- Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Multiple Loci Associated with Primary Tooth Development during Infancy

- Mutations in , Encoding an Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter ENT3, Cause a Familial Histiocytosis Syndrome (Faisalabad Histiocytosis) and Familial Rosai-Dorfman Disease

- Genome-Wide Identification of Binding Sites Defines Distinct Functions for PHA-4/FOXA in Development and Environmental Response

- Ku Regulates the Non-Homologous End Joining Pathway Choice of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Human Somatic Cells

- Nucleoporins and Transcription: New Connections, New Questions

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study in Asian Populations Identifies Variants in and Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Nucleoporins and Transcription: New Connections, New Questions

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání