-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaAnalysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' Disease

Legionella pneumophila and L. longbeachae are two species of a large genus of bacteria that are ubiquitous in nature. L. pneumophila is mainly found in natural and artificial water circuits while L. longbeachae is mainly present in soil. Under the appropriate conditions both species are human pathogens, capable of causing a severe form of pneumonia termed Legionnaires' disease. Here we report the sequencing and analysis of four L. longbeachae genomes, one complete genome sequence of L. longbeachae strain NSW150 serogroup (Sg) 1, and three draft genome sequences another belonging to Sg1 and two to Sg2. The genome organization and gene content of the four L. longbeachae genomes are highly conserved, indicating strong pressure for niche adaptation. Analysis and comparison of L. longbeachae strain NSW150 with L. pneumophila revealed common but also unexpected features specific to this pathogen. The interaction with host cells shows distinct features from L. pneumophila, as L. longbeachae possesses a unique repertoire of putative Dot/Icm type IV secretion system substrates, eukaryotic-like and eukaryotic domain proteins, and encodes additional secretion systems. However, analysis of the ability of a dotA mutant of L. longbeachae NSW150 to replicate in the Acanthamoeba castellanii and in a mouse lung infection model showed that the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system is also essential for the virulence of L. longbeachae. In contrast to L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae does not encode flagella, thereby providing a possible explanation for differences in mouse susceptibility to infection between the two pathogens. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis revealed that L. longbeachae has a less pronounced biphasic life cycle as compared to L. pneumophila, and genome analysis and electron microscopy suggested that L. longbeachae is encapsulated. These species-specific differences may account for the different environmental niches and disease epidemiology of these two Legionella species.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000851

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000851Summary

Legionella pneumophila and L. longbeachae are two species of a large genus of bacteria that are ubiquitous in nature. L. pneumophila is mainly found in natural and artificial water circuits while L. longbeachae is mainly present in soil. Under the appropriate conditions both species are human pathogens, capable of causing a severe form of pneumonia termed Legionnaires' disease. Here we report the sequencing and analysis of four L. longbeachae genomes, one complete genome sequence of L. longbeachae strain NSW150 serogroup (Sg) 1, and three draft genome sequences another belonging to Sg1 and two to Sg2. The genome organization and gene content of the four L. longbeachae genomes are highly conserved, indicating strong pressure for niche adaptation. Analysis and comparison of L. longbeachae strain NSW150 with L. pneumophila revealed common but also unexpected features specific to this pathogen. The interaction with host cells shows distinct features from L. pneumophila, as L. longbeachae possesses a unique repertoire of putative Dot/Icm type IV secretion system substrates, eukaryotic-like and eukaryotic domain proteins, and encodes additional secretion systems. However, analysis of the ability of a dotA mutant of L. longbeachae NSW150 to replicate in the Acanthamoeba castellanii and in a mouse lung infection model showed that the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system is also essential for the virulence of L. longbeachae. In contrast to L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae does not encode flagella, thereby providing a possible explanation for differences in mouse susceptibility to infection between the two pathogens. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis revealed that L. longbeachae has a less pronounced biphasic life cycle as compared to L. pneumophila, and genome analysis and electron microscopy suggested that L. longbeachae is encapsulated. These species-specific differences may account for the different environmental niches and disease epidemiology of these two Legionella species.

Introduction

Legionella longbeachae is one species of the family Legionellaceae that causes legionellosis, an atypical pneumonia that can be fatal if not promptly treated. While Legionella pneumophila is the leading cause of legionellosis in the USA and Europe, and is associated with around 91% of the cases worldwide, L. longbeachae is responsible for approximately 30% of legionellosis cases in Australia and New Zealand and nearly 50% in South Australia [1] and Thailand [2]. Two serogroups (Sg) are distinguished within L. longbeachae but most of the human cases of legionellosis are due to Sg1 strains [3],[4]. Interestingly, unlike L. pneumophila, which inhabits aquatic environments, L. longbeachae is found predominantly in potting soil and is transmitted by inhalation of dust from contaminated soils [4],[5].

Little is known about the biology and the genetic basis of virulence of L. longbeachae but a few studies suggest considerable differences with respect to L. pneumophila. In contrast, the intracellular life cycle of L. pneumophila is well characterized (for recent reviews see [6]–[8]). L. pneumophila replicates within alveolar macrophages inside a unique phagosome that excludes both early and late endosomal markers, resists fusion with lysosomes and recruits endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Within this protected vacuole L. pneumophila replicates and down-regulates the expression of virulence factors. It has been proposed that nutrient limitation then leads to the transition to transmissive phase bacteria that express many virulence-associated traits allowing the release and infection of new host cells [9]. This biphasic life cycle is observed both in vitro and in vivo as exponential phase bacteria do not express virulence factors and the bacteria fail to evade the destructive lysosomes and are delivered to the endocytic network and destroyed [9],[10]. The ability of L. pneumophila to replicate intracellularly is triggered at the post-exponential phase together with other virulence traits. Less is known about the intracellular life cycle of L. longbeachae and its virulence factors. Unlike L. pneumophila the ability of L. longbeachae to replicate intracellularly is independent of the bacterial growth phase [11]. Phagosome biogenesis is also different. Like L. pneumophila, the L. longbeachae phagosome is surrounded by endoplasmic reticulum and evades lysosome fusion but in contrast to L. pneumophila containing phagosomes the L. longbeachae vacuole acquires early and late endosomal markers [12].

Efficient formation of the L. pneumophila replication vacuole requires the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system (T4SS) [13]–[16] and probably more than 100 translocated effector proteins that modulate different host cell processes, in particular vesicle trafficking [17]–[19]. While L. longbeachae possesses all genes necessary to code a Dot/Icm T4SS [20], it is not known whether it is also essential for virulence and whether L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae share common effectors.

Another interesting difference between these two species is their ability to colonize the lungs of mice. While only A/J mice are permissive for replication of L. pneumophila, A/J, C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice are all permissive for replication of L. longbeachae [12],[21]. Resistance of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice to L. pneumophila has been attributed to polymorphisms in Nod-like receptor apoptosis inhibitory protein 5 (naip5) allele [22]–[24]. The current model states that L. pneumophila replication is restricted due to flagellin dependent caspase-1 activation through Naip5-Ipaf and early macrophage cell death by pyroptosis. Why L. longbeachae, in contrast to L. pneumophila, is able to replicate in macrophages of all three different mouse strains is still not understood.

In this study we report the complete genome sequencing and analysis of a clinical L. longbeachae Sg1 strain isolated in Australia and compare this genome to three L. longbeachae draft genome sequences (one Sg1 and two Sg2 strains) and the published genome sequences of four L. pneumophila strains [25]–[27]. In addition, we performed transcriptome analysis and virulence studies of a T4SS mutant of L. longbeachae. This has allowed us to propose answers for the questions raised above and brings exciting new insight into the varying adaptation to different ecological niches and different intracellular life cycles of Legionella species.

Results/Discussion

The L. longbeachae genomes are highly conserved and are 500 kb larger than those of L. pneumophila

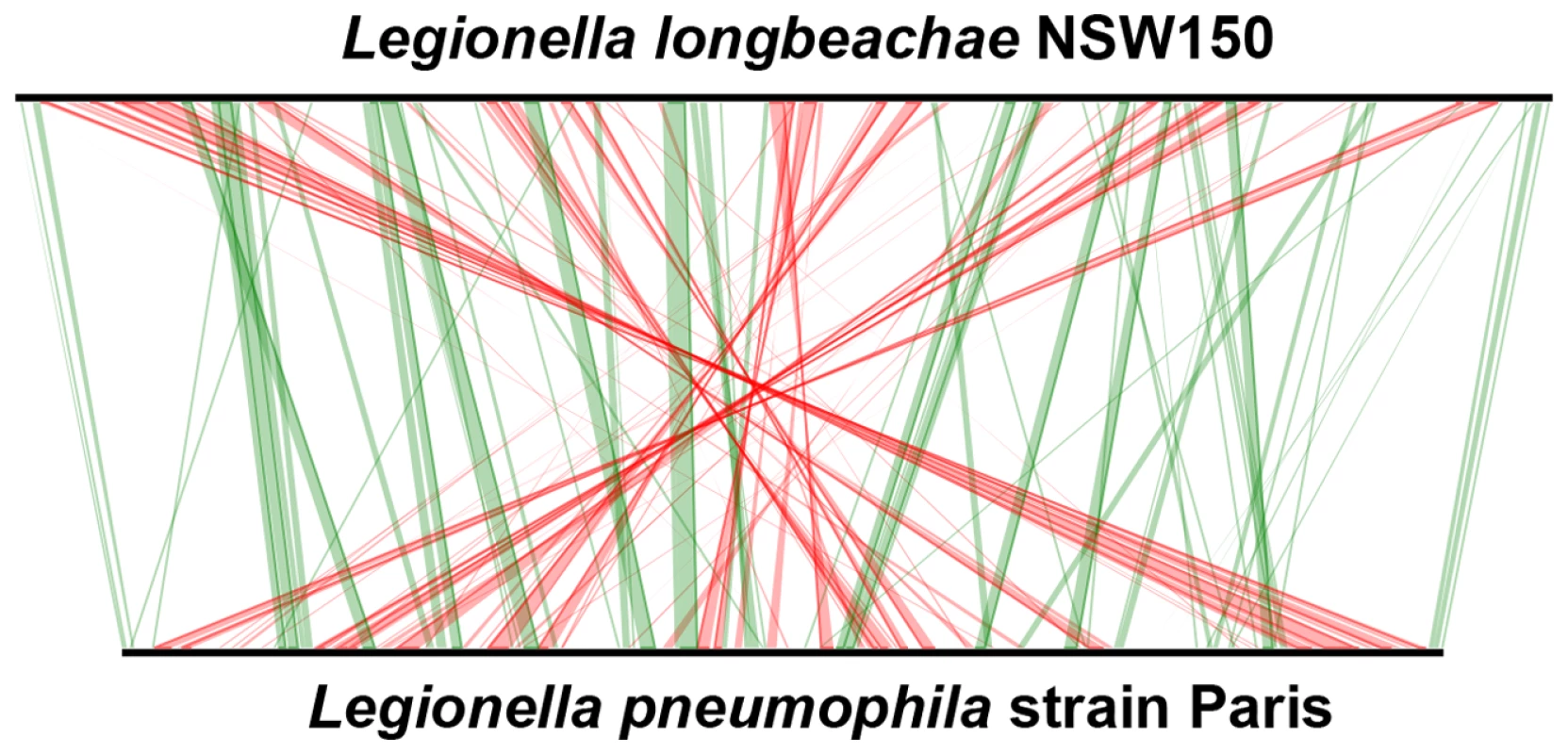

The L. longbeachae NSW150 genome consists of a 4,077,332-bp chromosome and a 71,826-bp plasmid with an average GC content of 37.11% and 38.19%, respectively (Table 1). A total of 3512 protein-encoding genes are predicted, 2046 (58.3%) of which have been assigned a putative function (Table S1, Figure S1). The L. longbeachae chromosome is about 500 kb larger than that of L. pneumophila and has a significantly different organization as seen in the synteny plot in Figure 1 and Figure S2. Moreover only 2290 (65.2%) L. longbeachae genes are orthologous to L. pneumophila genes, whereas 1222 (34.8%) are L. longbeachae specific with respect to L. pneumophila Paris, Lens, Philadelphia and Corby (defined by less than 30% amino acid identity over 80% of the length of the smallest protein, s Table S2). It was previously suggested that plasmid-encoded functions such as a two-component system, are important for L. longbeachae virulence [28]. Although no similarity was detected between the L. longbeachae plasmid here characterized and the 9kb partial plasmid sequence reported of strain L. longbeachae A5H5 [28], similar plasmids seem to circulate among different Legionella species, as 30 kb of the plasmid of strains Paris, Lens and NSW150, 18 kb of which encode transfer genes (traI – traA), encoded ORFs showing high amino acid sequence similarity (Figure S3).

Fig. 1. Whole-genome synteny map of L.longbeachae strain NSW150 and L. pneumophila strain Paris.

The linearized chromosomes were aligned and visualized by Lineplot in MAGE. Syntenic relationships comprising at least 8 genes are indicated by green and red lines for genes found on the same strand or on opposite strands, respectively. IS elements (pink), ribosomal operons (blue) and tRNAs (green) are also indicated. Tab. 1. General features of the completely sequenced L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae genomes.

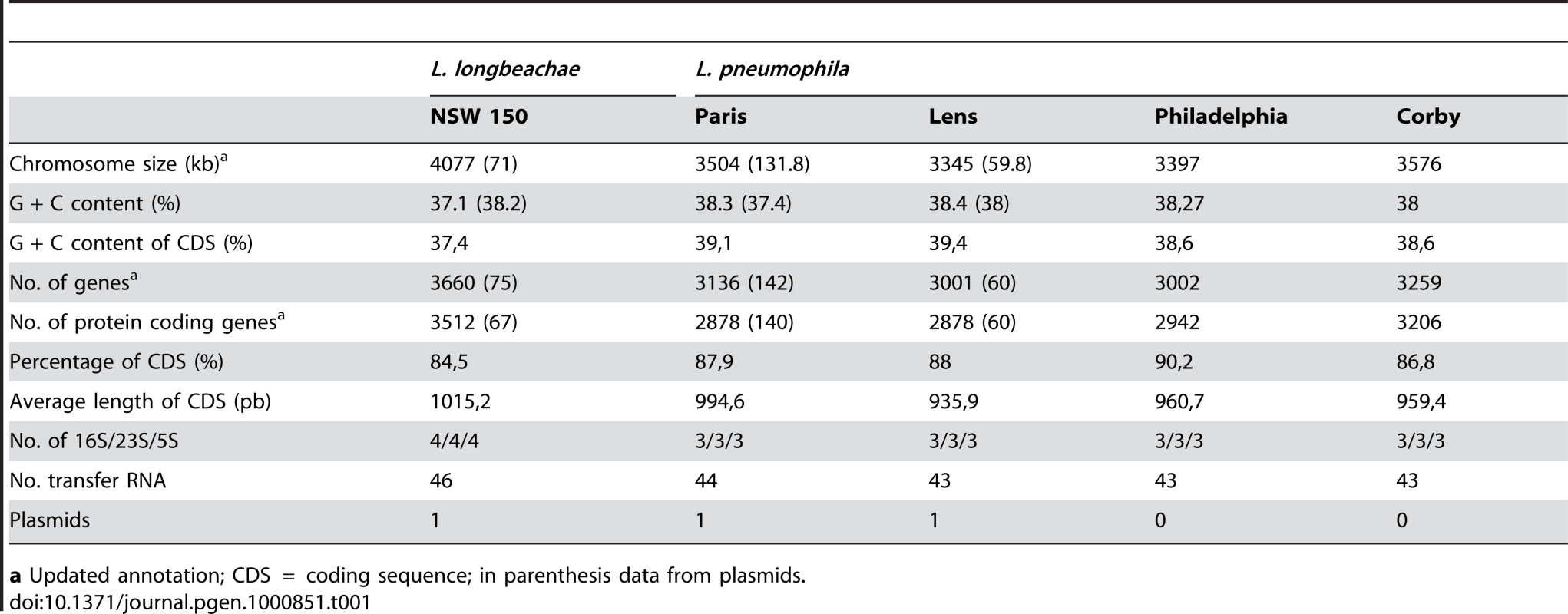

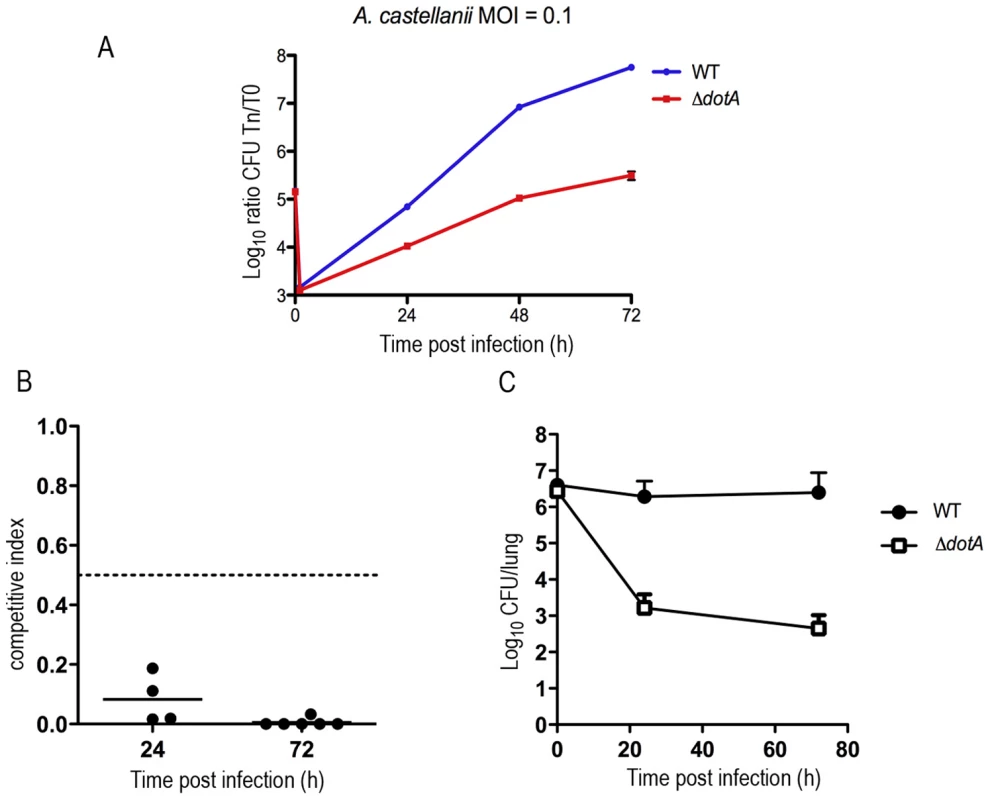

a Updated annotation; CDS = coding sequence; in parenthesis data from plasmids. With the aim of gaining further information on genome content and diversity of L. longbeachae we selected three additional strains, two isolated in the USA one in Australia for genome sequencing and analysis. L. longbeachae strain ATCC39642 (Sg1), strain 98072 (Sg2) and strain C-4E7 (Sg2) were deep sequenced using the Illumina technology and then compared to the genome of strain NSW150. We obtained a coverage of 93–96% for each genome with respect to the NSW150 genome (Table 2). The sequences were assembled into 93, 106 and 89 contigs larger than 0.5kbs that were further analyzed regarding gene content and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). High quality SNPs were detected by mapping the Illumina reads on the finished NSW150 genome sequence. This revealed a high conservation in genome size, content, organization and a low SNP number among the four L. longbeachae genomes (Table 2). Interestingly, in contrast to L. pneumophila where strains of the same Sg may have very different gene content [25],[29], the two strains of L. longbeachae each belonging to Sg1 or Sg2, respectively, showed highly conserved genomes. Comparison of the two Sg1 genomes identified 1611 SNPs of which 1426 are located in only seven chromosomal regions mainly encoding putative mobile elements, whereas the remaining 185 SNPs were evenly distributed around the chromosome (Figure S4). In contrast, the SNP number between two strains of different Sg was higher, with about 16 000 SNPs present between Sg1 and Sg2 strains (Table 1, Figure S4). This represents an overall polymorphism of less than 0.4%, which is significantly lower than the polymorphism of about 2% between L. pneumophila Sg1 strains Paris and Philadelphia. The low SNP number and relatively homogeneous distribution of the SNPs around the chromosome (Figure S4) suggest recent expansion for the species L. longbeachae.

Tab. 2. General features of the L. longbeachae draft genomes obtained by new generation sequencing.

*N50 contig size, calculated by ordering all contig sizes and then adding the lengths (starting from the longest contig) until the summed length exceeds 50% of the total length of all contigs (half of all bases reside in a contiguous sequence of the given size or more); The dot/icm type IVB secretion system is highly conserved, and many other secretion systems are present

L. pneumophila has a rather exceptional number and wide variety of secretion systems for efficient and rapid delivery of effector molecules into the phagocytic host cell underlining the importance of protein secretion for this pathogen. This also holds true for L. longbeachae. We identified the genes coding the Lsp type II secretion machinery, however, 45% of the type II secretion system substrates described for L. pneumophila [30],[31] are absent from L. longbeachae. Furthermore, the twin arginine translocation system (TAT) and three putative type I secretion systems (T1SS) are present. However, the Lss T1SS might not be functional in L. longbeachae as only LssXYZA are conserved (55 to 82% identity with strain Paris) and the two essential components LssB (ABC transporter-ATP binding) and LssD (HlyD family secretion protein) are missing. In contrast, the two additional putative T1SS, encoded by the genes llo2283-llo2288 and llo0441-llo0444 appeared to be functional. Furthermore, two HlyD-like proteins (Llo2901 and Llo0979) localized next to ABC transporters (Llo2900 and Llo0980-Llo0981) were present, but no contiguous outer membrane protein was found. However, these proteins could also be part of T1SS and function together with a genetically unlinked outer membrane component, similar to what is seen for the Hly T1SS of Escherichia coli and may thus constitute two additional T1SS. Finally, L. longbeachae encodes four type IV secretion systems (T4SS). The Lvh T4ASS of L. pneumophila is absent from L. longbeachae but we identified three other type-IVA secretion systems. One T4ASS is present on the plasmid and the other two are embedded on putative mobile genomic islands (GI) in the chromosome. llo1819-llo1929 (GI-1) of around 120 kb is bordered by Ser and Arg tRNAs and carries a gene coding for a phage integrase (llo1819). The second cluster (GI-2) of 106 kb spans from the integrase coding gene llo2859 to llo2960ab and is also bordered by a Met tRNA. Most of the proteins encoded on GI-2 are of unknown function. However both islands code for several proteins, which may be dedicated to stress response. On GI-1, Llo1862 and Llo1863llo1863 are homologous to DNA polymerase IV subunit C and D respectively, involved in the SOS repair pathway. On GI-2 are the OsmC-like protein Llo2923, the putative universal stress proteins Llo2926, Llo2927, Llo2929 and the predicted trancriptional regulator Llo2913 with S24 peptidase domain. Indeed, the S24 peptidase family includes LexA, a transcriptional repressor of SOS response genes to DNA damage. Several transporters were also identified on GI-2: Llo2918 of the MFS superfamily, the Na/H exchange protein Llo2930 and the putative T1SS proteins Llo2900 and Llo2901 discussed above. It possesses in addition a putative restriction/modification system encoded by llo2865, llo2866 and llo2867.

Central to the establishment of the intracellular replicative niche and to L. pneumophila virulence is the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. This T4BSS is also present in L. longbeachae and the general organization of the genomic region encoding it is conserved with protein identities of 47 to 92% with respect to that of L. pneumophila. This is similar to what has been reported previously for other Legionella species [20]. In L. longbeachae the icmR gene is replaced by the ligB gene, however, the encoded proteins have been shown to perform similar functions [32],[33]. Here we found that IcmE/DotG of L. longbeachae is 477 amino acids larger than that of L. pneumophila. DotG is part of the core transmembrane complex of the secretion system and it is composed of three domains: a transmembrane N-terminal domain, a central region composed of 42 repeats of 10 amino acid and a C-terminal region homologous to VirB10. The central region of DotG from L. longbeachae comprises approximately 90 repeats. It will be challenging to understand the possible impact of this modification on the function of the type-IV secretion system.

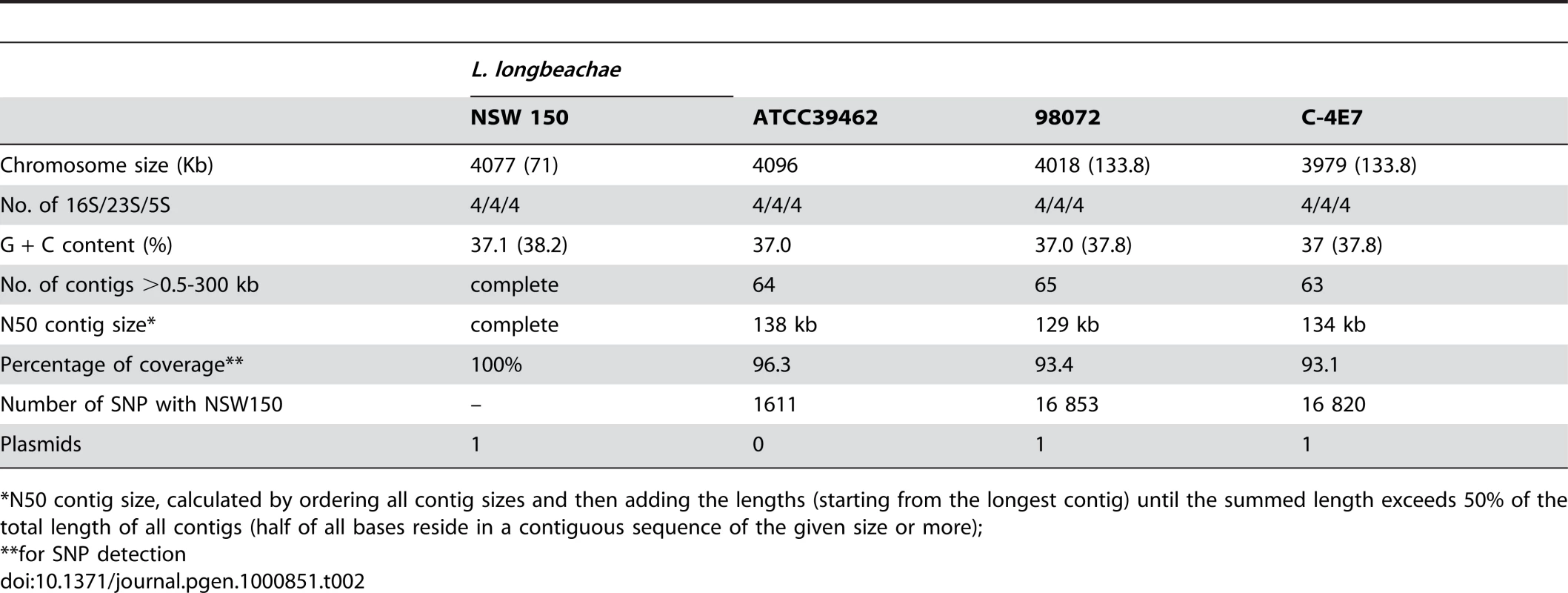

The dot/icm type IV secretion system of L. longbeachae is essential for virulence in Acanthamoeba castellanii and in pulmonary mouse infection

To test whether the Dot/Icm T4SS is essential for virulence of L. longbeachae we constructed a deletion mutant in the L. longbeachae NSW150 gene llo0364, homologous to dotA of L. pneumophila and tested its ability to replicate compared to the wild type strain in A. castellanii and the lungs of A/J mice. We found that L. longbeachae NSW150 infects A. castellanii in a comparable manner to L. pneumophila and that the dotA mutant was strongly attenuated for intracellular growth in A. castellanii, similar to what is seen for a L. pneumophila dotA mutant (Figure 2A). Recently Gobin and colleagues established an experimental model of intratracheal L. longbeachae infection in A/J mice [21]. Here we compared the ability of the L. longbeachae dotA mutant to compete with wild type L. longbeachae in the lungs of A/J mice. In mixed infections, we observed that the dotA mutant was outcompeted by the wild type strain 24 h and 72 h after infection (Figure 2B). The competitive index of the dotA mutant was calculated by dividing the ratio of mutant to wild type bacteria after infection with the ratio of mutant to wild type bacteria in the inoculum. A competitive index of less than 0.5 is considered a significant attenuation [34]. The competitive index was less than 0.5 at both time-points indicating rapid loss of the dotA mutant following infection. In single infections, the L. longbeachae dotA mutant was also dramatically attenuated for replication (Figure 2C). Thus, the Dot/Icm secretion system was essential for the virulence of L. longbeachae.

Fig. 2. Intracellular growth of the wild-type and the dotA mutant strain in mouse and amoeba infection.

(A) Intracellular replication of L. longbeachae in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Blue, wild-type L. longbeachae strain NSW150; Red, dotA::Km mutant. Results are expressed as log10 CFU. Each time point (in hours, x-axis) represents the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. Infections were performed at 37°C. (B) CI values from mixed infections of A/J mice. Mice were inoculated with approximately 106 CFU of each strain under investigation and were sacrificed at 24 h or 72 h after infection to examine the bacterial content of their lungs. Competition experiment between L. longbeachae and the dotA::Km mutant representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Single infections of A/J mice with L. longbeachae wt and the dotA::Km mutant strain. Results are expressed as log10 CFU. Note: to maintain numbers in the lung L. longbeachae must be replicating Non-replicating bacteria are cleared in this infection model over 72 h (eg. dotA mutant) [21]. L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila encode different sets of secreted Dot/Icm substrates and virulence genes

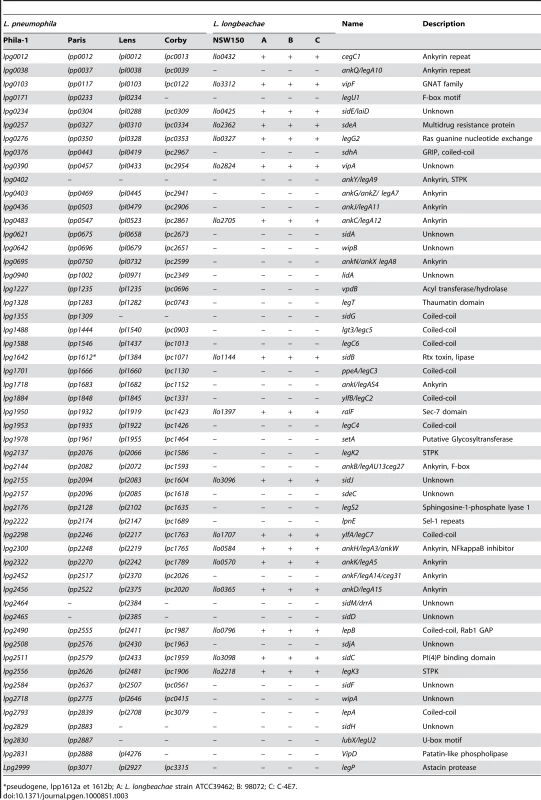

Despite the high degree of conservation of the Dot/Icm T4SS components between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae the Dot/Icm substrates were not highly conserved. Indeed 66% of reported L. pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates were absent from L. longbeachae (Table 3 and Table S3). Instead, we predicted 51 new putative Dot/Icm substrates specific for L. longbeachae that encode eukaryotic-like domains and all but one contained the secretion signal described by Nagai and colleagues [35] and many also the additional criteria defined by Kubori and colleagues [36] (Table 4). Interestingly, the distribution of both, the conserved and the newly identified substrates of L. longbeachae among the four sequenced strains was highly conserved (Table 3 and Table 4). Both L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae replicate within a vacuole that recruits endoplasmic reticulum. Several effector proteins have been shown to contribute to the ability of L. pneumophila to manipulate host cell trafficking events resulting in this association. The effector proteins SidJ, RalF, VipA, VipF, SidC, YlfA and LepB which contribute to trafficking or recruitment and retention of vesicles to L. pneumophila vacuoles were conserved in L. longbeachae, but VipD, SidM/DrrA and LidA which interfere also with these events are absent from the L. longbeachae genome; however VipD and SidM/DrrA are also not present in all the L. pneumophila genomes sequenced.

Tab. 3. Distribution of selected Dot/Icm substrates of L. pneumophila in the L. longbeachae genomes.

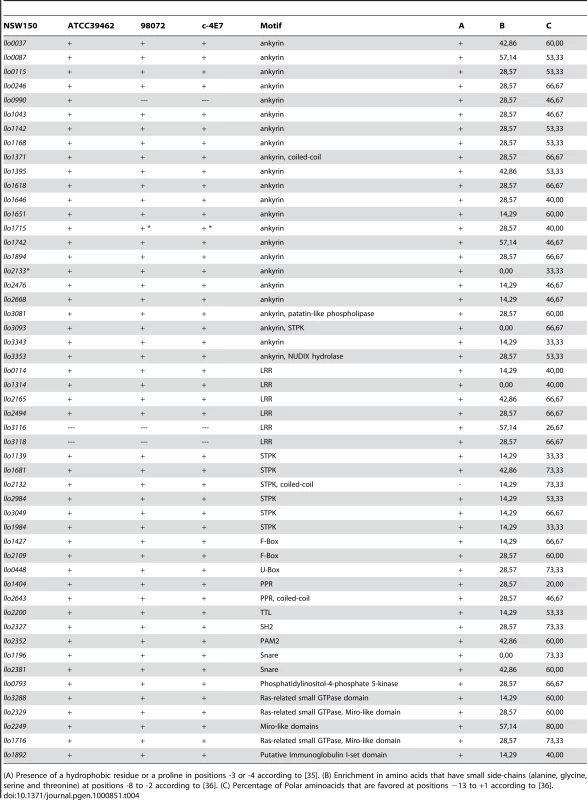

*pseudogene, lpp1612a et 1612b; A: L. longbeachae strain ATCC39462; B: 98072; C: C-4E7. Tab. 4. Putative new type IV secretion substrates specific for L. longbeachae.

(A) Presence of a hydrophobic residue or a proline in positions -3 or -4 according to [35]. (B) Enrichment in amino acids that have small side-chains (alanine, glycine, serine and threonine) at positions -8 to -2 according to [36]. (C) Percentage of Polar aminoacids that are favored at positions −13 to +1 according to [36]. Although L. pneumophila also communicates with early and late endosomal vesicle trafficking pathways [37]–[39], a major difference in the phagosome maturation of the two species is that the L. longbeachae phagosome acquires early and late endocytic markers. Several proteins identified specifically in the genome of L. longbeachae may contribute to these differences. First, L. longbeachae encodes a family of Ras-related small GTPases (Llo3288, Llo2329, Llo1716 and Llo2249) (Figure S5), which may also be involved in vesicular trafficking and account for the specificities of the L. longbeachae life cycle. Remarkably, Llo3288, Llo2329 and Llo1716 are the first small GTPases of the Rab subfamily described in a prokaryote. L. pneumophila is also known to exploit monophosphorylated host phosphoinositides (PI) to anchor the effector proteins SidC, SidM/DrrA, LpnE and LidA to the membrane of the replication vacuole [34], [40]–[44]. L. longbeachae may employ an additional strategy to interfere with the host PI as Llo0793 is homologous to a mammalian PI metabolizing enzyme phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase and it is tempting to speculate that this protein allows direct modulation of the host cell PI levels.

As another strategy to alter host trafficking pathways, L. pneumophila is able to target microtubule-dependent vesicular transport. AnkX/AnkN, for example, prevents microtubule-dependent vesicular transport interfering with the fusion of the L. pneumophila-containing vacuole with late endosomes [45]. AnkX/AnkN is absent from L. longbeachae, however L. longbeachae did encode a putative tubulin-tyrosine ligase (TTL) Llo2200, which adds to the 19 bacterial TTL identified to date. TTL catalyzes the ATP-dependent post-translational addition of a tyrosine to the carboxy terminal end of detyrosinated alpha-tubulin. Although the exact physiological function of alpha-tubulin has so far not been established, it has been linked to altered microtubule structure and function [46]. Besides AnkX/AnkN, a large family of ankyrin repeat constitutes L. pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates. Interestingly, 23 of the 29 ankyrin proteins identified in the L. pneumophila strains are absent from the L. longbeachae genome, however L. longbeachae encodes 23 specific ankyrin repeat proteins (Table 4).

L. pneumophila is also able to interfere with the host ubiquitination pathway. The U-box protein LubX, which possesses in vitro ubiquitin ligase activity specific for the eukaryotic Cdc2-like kinase Clk1 [36], is absent from L. longbeachae. However, llo0448 encodes a predicted U-box protein. None of the three L. pneumophila F-box proteins, which may also exploit this pathway, are conserved in L. longbeachae, but we identified two new putative F-box proteins Llo1427 and Llo2109 (Table 4). Thus, although the specific proteins may not be conserved, the eukaryotic-like protein-protein interaction domains found in L. pneumophila are also present in L. longbeachae.

L. longbeachae also encodes several proteins with eukaryotic domains that are not present in L. pneumophila. One is the above-mentioned protein Llo2200 encoding a TTL domain. A second is Llo2327, the first bacterial protein that encodes an Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain. SH2 domains, in eukaryotes, have regulatory functions in various intracellular signaling cascades. Furthermore, L. longbeachae encodes two proteins (Llo1404 and Llo2643) with pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) domains. This family seems to be greatly expanded in plants, where they appear to play essential roles in organellar RNA metabolism [47]–[49]where they appear to play essential roles in RNA/DNA metabolism, where. Only 12 bacterial PPR domain proteins have been identified to date, all encoded by two species, the plant pathogens Ralstonia solanacearum and the facultative photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides.

L. longbeachae encodes putative toxins

Recently, a family of cytotoxic glucosyltransferases produced by L. pneumophila (Lgt) and related to the group of clostridial glucosylating cytotoxins has been described [50],[51]. The three studied enzymes Lgt1/2/3 target one host molecule, eEF1A, and have been implicated in inhibition of eukaryotic protein synthesis and target-cell death [52]. L. longbeachae encodes two putative specific cytotoxic glucosyltransferases Llo1721 and Llo1578. They share only low homology with the L. pneumophila Lgt proteins with 23% protein identity over 62% of the protein length and 36% protein identity over 32% of the length, respectively. However, the DXD motif that is critical for enzymatic activity of clostridial enzymes is conserved suggesting that these enzymes might also be active in L. longbeachae. We also identified Llo3231 as another putative specific glucosyltransferase with a DXD motif, distantly related to the L. pneumophila SetA protein (23% protein identity over 67% of the protein length). SetA is known to cause delay in vacuolar trafficking [53], however its glucosylating activity remains to be established. In contrast, L. longbeachae does not encode a homologue of the L. pneumophila structural toxin protein RtxA, however we identified a homolog of the TcaZ toxin (Llo1558) present in the insect pathogen Photorhabdus luminescens [54].

Many metabolic features of the genome of L. longbeachae reflect its soil habitat

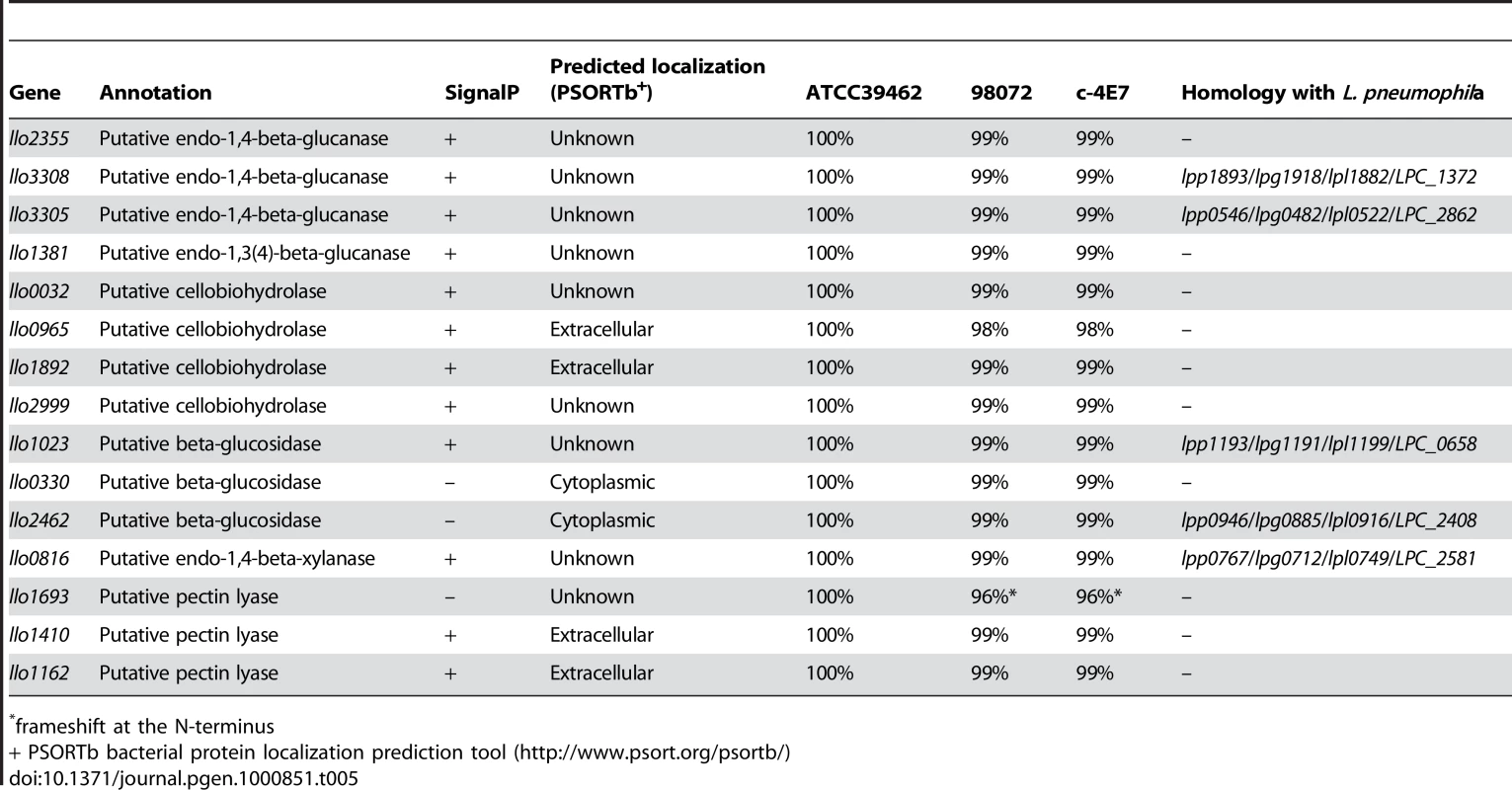

L. longbeachae encodes a variety of proteins probably devoted to the metabolism of compounds present in plant cell walls, going in hand with the fact that that bacterium can be isolated from composted plant material. The main components of the plant cell wall are cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin. Cellulose utilization by microorganisms involves endo-1,4-beta-glucanases, cellobiohydrolases and β-glucosidases, that act synergically to convert cellulose to glucose. Examination of the L. longbeachae genome sequence revealed the presence of twelve such cellulolytic enzymes. Five glucanases, four cellobiohydrolases and three β-glucosidases are present. Interestingly, L. pneumophila also encodes two putative endo-1,4-beta-glucanases and one putative β-glucosidase but does not encode any cellobiohydrolase.

Within the plant cell wall, the cellulose microfibrils are linked via hemicellulosic tethers to form the cellulose-hemicellulose network, which is embedded in the pectin matrix. To gain access to cellulose in plant material, pectin and hemicellulose hydrolysis is necessary. Interestingly, L. longbeachae encodes three pectin lyases (Llo1693, Llo1410, Llo1162). The last two proteins possess a signal peptide and may therefore be secreted. Pectin lyases are virulence factors usually found in phytopathogenic microorganisms that degrade the pectic component of the plant cell wall. In addition to these specific enzymes and similar to L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae encodes a protein homologous to endo-1,4-beta-xylanase. Endo-1,4-beta-xylanase hydrolyses xylan the most common hemicellulose polymer in the plant kingdom and the second most abundant polysaccharide on earth. So, unlike L. pneumophila, which does not possess cellobiohydrolase and pectin lyase, L. longbeachae seems to be fully equipped to utilize cellulose as a carbon source (Table 5). Soil bacteria also often hydrolyse chitin by the means of chitinases to use it as a carbon source. Chitin originates mainly from the cell wall of fungi and cuticles of crustaceans or insects. In line with the fact that L. longbeachae is isolated from soil, we found two chitinases (Llo0050, Llo1558) that are predicted to be secreted proteins. However, the homologue of ChiA from L. pneumophila that was shown to be involved in infection of lungs of A/J mice [31] is absent from L. longbeachae.

Tab. 5. Predicted L. longbeachae enzymes that may be involved in cellulose degradation.

frameshift at the N-terminus Interestingly, L. longbeachae encodes a putative cyanophycin synthase (Llo2537) and therefore may be able to synthesize cyanophycin. Cyanophycin is an amino acid polymer composed of an aspartic acid backbone and arginine side groups. It serves as a storage compound for nitrogen, carbon and energy in many cyanobacteria. Acinetobacter baylyi strain ADP1 was the first non-cyanobacterial strain shown to synthesize cyanophycin, a metabolic capacity that is still restricted to only few prokaryotes [55]–[58]. L. longbeachae also harbors a putative cyanophycinase (Llo2536) enabling the degradation of cyanophycin to dipeptides and a dipeptidase (Llo2535) necessary to hydrolyze beta-Asp-Arg dipeptides. L. longbeachae may thus be able to completely utilize cyanophycin, providing a mechanism for energy supply under substrate-limited conditions.

Genome and electron microscopy analysis indicates that L. longbeachae encodes a capsule

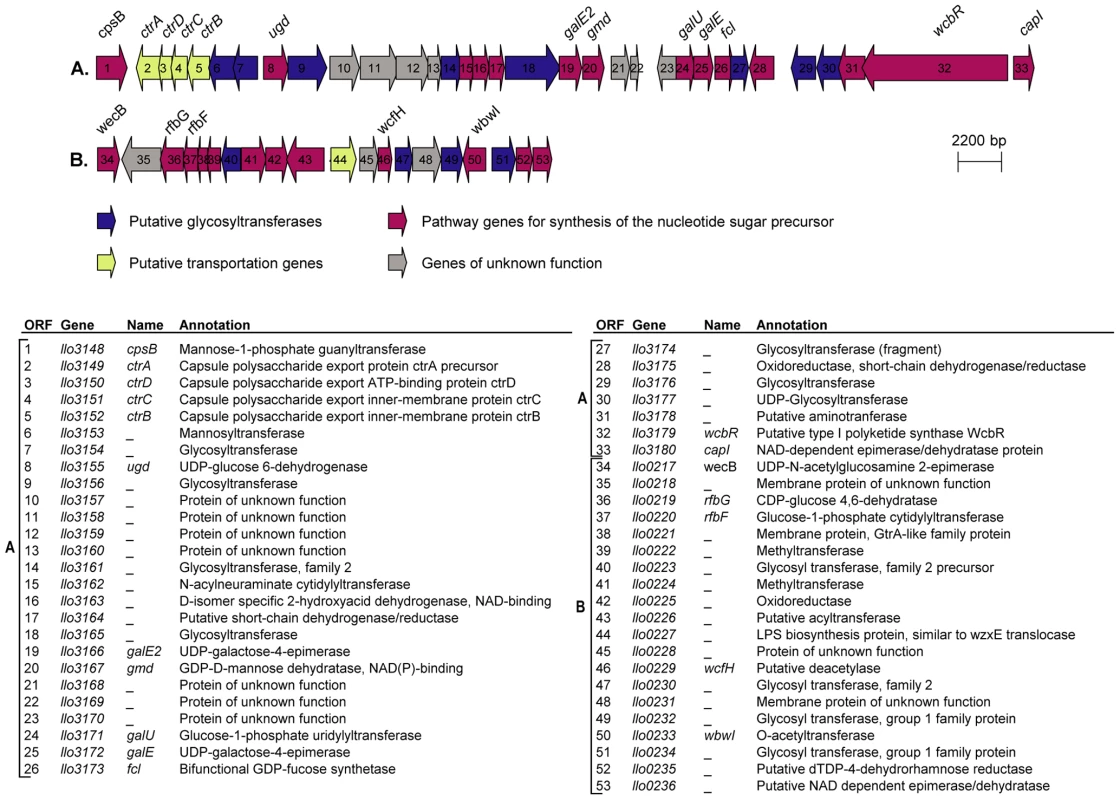

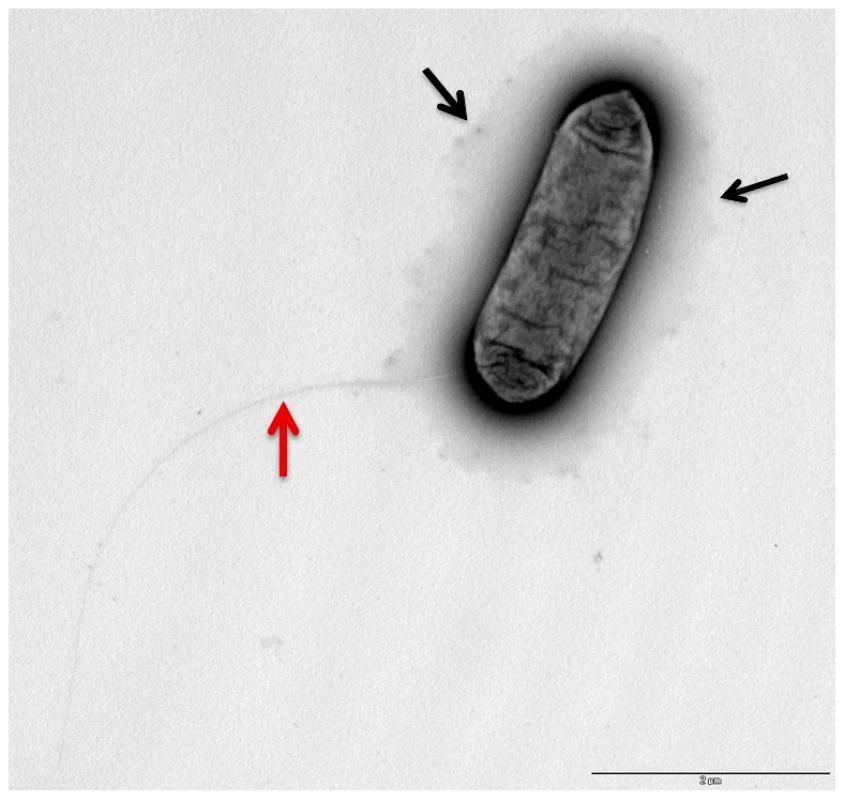

In the genome of L. longbeachae NSW150 we identified two gene clusters encoding proteins that are predicted to be involved in production of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and/or capsule (Figure 3). Neither shared homology with the L. pneumophila LPS biosynthesis gene cluster. One region of 48 kb spans from llo3148 to llo3180 (Figure 3A) and the second of 24 kb from llo0217 to llo0236 (Figure 3B). In total they contain 26 genes for synthesis of the nucleotide sugar precursor, 12 genes encoding putative glycosyltransferases, 5 polysaccharide translocation genes including homologs of the ctrABCD capsule transport operon of N. meningitidis, and 10 genes of unknown function (Table S4). The finding that L. longbeachae might be encapsulated was further substantiated by electron microscopy analysis. Figure 4 shows that a capsule-like structure surrounds the bacteria.

Fig. 3. Putative capsule and LPS encoding loci in the genome of L. longbeachae.

(A) 48 kb chromosomal region highly conserved in the four L. longbeachae genomes sequenced putatively encoding the capsular biosynthesis genes. (B) 24 kb chromosomal region differing between Sg1 and Sg2 isolates putatively encoding the lippolysaccaride biosynthesis genes of L. longebachae. Colors indicate different classes of genes: magenta, synthesis pathway of nucleoside sugar precursors; blue, glycosyltranferase; yellow transportation; grey, genes of unknown. Fig. 4. Electron microscopy showing the presence of capsule like structures.

Transmission electron micrographs of L. longbeache cells cultured in BYE broth to post exponential growth phase (OD600 3.8). Black arrows, puative capsule structures, red Arrow, putative pili. Gene clusters encoding the core lipopolysaccharide of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae are not conserved; however we identified in the genome of L. longbeachae homologs of L. pneumophila lipidA biosynthesis genes. Llo2684, Llo1461, Llo2686 and Llo0524 are homologous to LpxA, LpxB, LpxD and WaaM lipidA biosynthesis proteins with respectively 84%, 68%, 60% and 78% of identity. Predictions deduced from the sequence analysis of strain NSW150 did not clarify which region was coding for the LPS and which for the capsule. Further insight into the LPS and capsule encoding regions came from the comparison of this region among the four L. longbeachae genomes sequenced. The 24 kb region B is identical between the two Sg1 strains sequenced and identical between the two Sg2 strains analyzed, but the Sg1 and Sg2 strains differed from each other in an approximately 10 kb region carrying glycosyltransferases, methyltransferases, and LPS biosynthesis proteins (Figure S6). In contrast the putative capsule encoding region A was highly conserved among all four strains sequenced except for a region carrying three genes, that differed among all four strains independent of the Sg. However, as it is not known whether the Sg specificity of L. longbeachae is defined by its capsule or by LPS, further studies are necessary to clearly define the function of the proteins encoded in these two genomic regions.

L. longbeachae does not encode flagella explaining differences in mouse susceptibility as compared to L. pneumophila

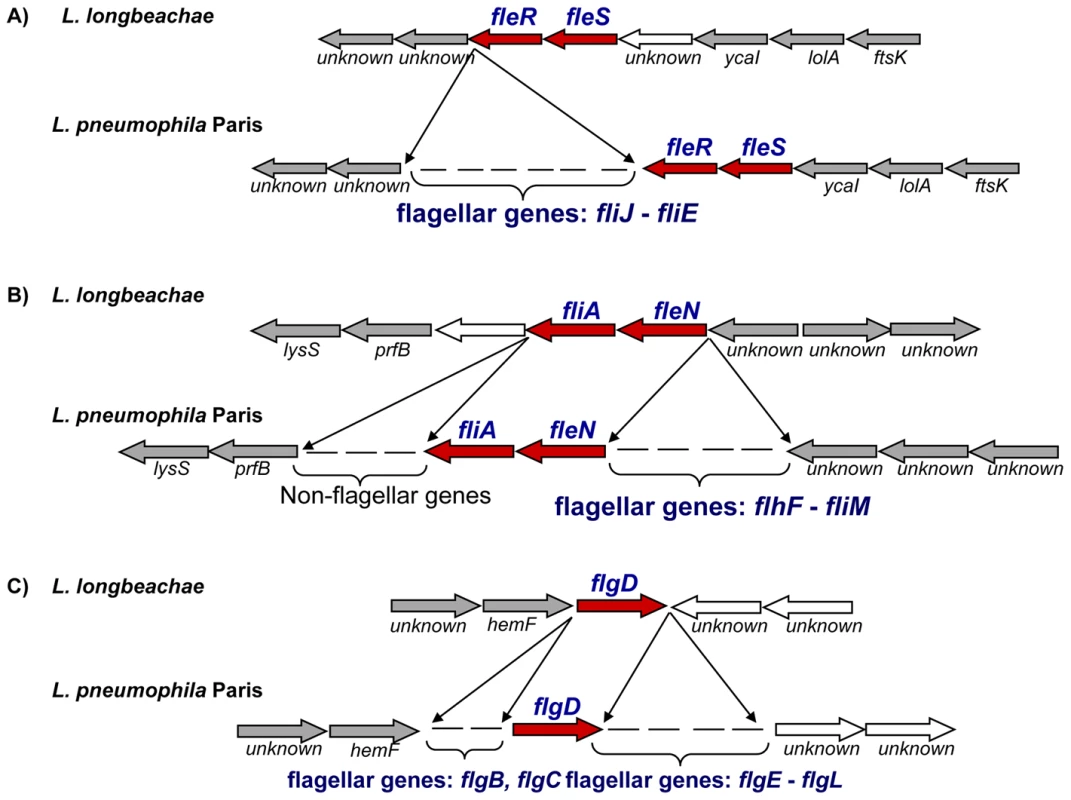

Cytosolic flagellin of L. pneumophila triggers Naip5-dependent caspase-1 activation and subsequent proinflammatory cell death by pyroptosis in C57BL/6 mice rendering these mice resistant to infection with L. pneumophila [22]–[24], [59]–[62]. In contrast, caspase-1 activation does not occur upon infection of C57BL/6 and A/J mice macrophages with L. longbeachae, which is then able to replicate. One possible explanation has been that due to a lack of pore-forming activity, L. longbeachae flagellin may not have access to the cytoplasm of the macrophage where it is thought to be involved in caspase-1 activation. Alternatively, L. longbeachae flagellin may not be recognized by the Naip5 pathway [11]. Genome analysis clarified this issue, as we found that L. longbeachae does not carry any flagellar biosynthesis genes except the sigma factor FliA, the regulator FleN, the two-component system FleR/FleS and the flagellar basal body rod modification protein FlgD. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 5, all genes bordering flagellar gene clusters were conserved between L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila, suggesting deletion of these regions from the L. longbeachae genome. Furthermore, not a single homologue of flagellar biosynthesis genes could be identified in other parts of the genome. Analysis of the three additional genome sequences of strains L. longbeachae ATCC39642, 98072 and C-4E7 confirmed the results. To further investigate this unexpected result, we designed primers in the conserved flanking genes to analyze these genomic regions in 15 L. longbeachae strains. All strains tested, eleven of Sg1 and four of Sg2, displayed the same organization as the sequenced strain (Table S5). According to these results, we propose that L. longbeachae fails to activate caspase-1 due to the lack of flagellin, which may also partly explain the differences in mouse susceptibility to L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae infection. The putative L. longbeachae capsule may also contribute to this difference.

Fig. 5. Alignment of the chromosomal regions of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae coding the flagella biosynthesis genes.

The comparison shows that all except the regulatory genes are missing in L. longbeachae. Red, conserved regulator encoding genes, grey arrows orthologous genes among the genomes, white arrows, non orthologues genes. Although L. longbeachae does not encode flagella, it encodes a putative chemotaxis system. Chemotaxis enables bacteria to find favorable conditions by migrating towards higher concentrations of attractants. The chemotactic response is mediated by a two-component signal transduction pathway, with the histidine kinase CheA and the response regulator CheY, putatively encoded by the genes llo3302 and llo3303 respectively, in the L. longbeachae genome. Furthermore, two homologues of the ‘adaptor’ protein CheW (encoded by llo3298, llo3300) that associate with CheA or cytoplasmic chemosensory receptors are present. Ligand-binding to receptors regulates the autophosphorylation activity of CheA in these complexes. The CheA phosphoryl group is subsequently transferred to CheY, which then diffuses away to the flagellum where it modulates motor rotation. Adaptation to continuous stimulation is mediated by a methyltransferase CheR encoded by llo3299 in L. longbeachae. Together, these proteins represent an evolutionarily conserved core of the chemotaxis pathway, common to many bacteria and archea [55],[63]. A similar chemotaxis system is also present in L. drancourtii LLAP12 [64] but it is absent from L. pneumophila. The flanking genomic regions are highly conserved among L. longbeachae and all L. pneumophila strains sequenced, suggesting that L. pneumophila, although it encodes flagella has lost the chemotaxis system encoding genes.

We also observed using electron microscopy (Figure 4) that L. longbeachae possesses a long pilus-like structure. Indeed, all genes necessary to code for type IV pili are present in the genome of L. longbeachae and are, with 63–88% amino acid similarity, highly conserved between L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila. Taken together genome analysis revealed interesting features of the Legionella genomes: both encode pilus-like structures, in contrast L. longbeachae encodes a chemotaxis system but no flagella, and L. pneumophila encodes flagella but no chemotaxis system. It will be an interesting aspect of future research to understand these particular features of the two Legionella species.

The regulatory repertoire of L. longbeachae suggests different adaptation mechanisms as compared to L. pneumophila

Similar to the L. pneumophila genomes and consistent with its intracellular lifestyle, the regulatory repertoire of L. longbeachae is rather small. Genome analysis identified 121 transcriptional regulators (113–116 in the four sequenced L. pneumophila genomes), which represent only 3.0% of the predicted genes (Table S6). Similar to L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae encodes six putative sigma factors, RpoD, RpoH, RpoS, RpoN, FliA and the ECF-type sigma factor RpoE.

The most abundant class of regulators of L. pneumophila is the GGDEF/EAL family (24 or 23 in all L. pneumophila genomes sequenced). This is significantly different in L. longbeachae, as we identified only 14 GGDEF/EAL domain-containing regulators, despite the larger size of the L. longbeachae genome. Furthermore, this group of regulators may fulfill specific functions in L. longbeachae, since most of the regulators possess no orthologs in the L. pneumophila genomes (Table S6). The function of these regulators in L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae is unknown, but in other bacteria these regulators play a role in aggregation, biofilm formation, twitching motility or flagella regulation. In L. pneumophila it was suggested, as deduced from gene expression analysis, that some of the GGDEF/EAL regulators may play a role in modulating flagella expression [65],[66], thus the lower number of GGDEF/EAL domain-containing proteins of L. longbeachae may in part be related to the missing flagellum.

Another difference in the regulatory repertoire of the two Legionella species was observed for two component systems. There are 14 response regulators and 13 histidine kinases in L. pneumophila, and 17 response regulators and 16 histidine kinases in the L. longbeachae genome, but only half of the L. longbeachae response regulators possess an ortholog in L. pneumophila. For example the recently described two-component system LqsS/LqsR that is part of a quorum sensing system in L. pneumophila is missing in L. longbeachae [67]–[69]. Two-component systems are involved in signal transduction pathways that enable bacteria to sense, respond, and adapt to a wide range of environments, stressors, and growth conditions [70]. Different two-component systems may be linked to the different environments to which L. longbeachae has to adapt compared to L. pneumophila.

In L. longbeachae, cyclic AMP may also transduce cellular signals as the genome encodes eight class III adenylate cyclases (Llo0181, Llo1751, Llo2196, Llo1669, Llo0753, Llo1197, Llo1216, Llo3304) of which only one (Llo0181) is also conserved in L. pneumophila. LadC, an adenylate cyclase of L. pneumophila that was shown to have a significant role in the initiation of infection in vitro and in vivo [71], is absent from L. longbeachae. As shown for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, these class III adenylate cyclases may sense environmental signals ranging from nutritional content of the surrounding media to the presence of host cells and control virulence gene expression accordingly [72]. Furthermore, 13 proteins containing cAMP binding motifs were identified, only one of which is shared with L. pneumophila, again indicating specific regulatory circuits for L. longbeachae. This high number of proteins that may sense cAMP indicates the potential importance of this signaling molecule in L. longbeachae.

In contrast, the regulators shown to be important for growth phase and life cycle dependent gene expression, such as the two component system LetA/LetS (Lllo2653/llo1235), the RNA-binding protein CsrA (Llo2071), the two small RNAs RsmY and RsmZ regulating CsrA [66],[73], SpoT (Llo0908) and RelA (Llo1756) are conserved in L. longbeachae. Likewise, the two-component systems PmrAB (Llo1159/Llo1158) and CpxRA (Llo1781/Llo1782) that regulate the Dot/Icm T4SS system and some of its substrates are both conserved in L. longbeachae [74]–[76].

Global gene expression analysis reveals differences in the L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila life cycles

It has been shown in several studies that L. pneumophila exhibits at least two developmental stages, a replicative/avirulent and a transmissive/virulent phase that are each characterized by the expression of specific traits [9]. These stages are also reflected in a major shift in the gene expression program of L. pneumophila between the two phases of its life cycle [65]. In order to investigate, whether L. longbeachae had a similar biphasic life cycle we studied its gene expression program in exponential and post exponential growth phase in vitro. A multiple-genome microarray was constructed containing 10 692 gene-specific oligonucleotides representing 3567 genes predicted in the genome and on the plasmid and 3010 oligonucleotides specific for intergenic regions. RNA of in vitro grown bacteria was sampled at OD 2.5 (exponential growth) and at OD 3.7 (post exponential growth) and the global gene expression program was compared.

Overall, 187 genes in L. longbeachae were upregulated in the exponential (E) phase (likewise, downregulated in the postexponential phase, Table S7), and 313 genes were upregulated in the postexponential (PE) phase (downregulated in the E phase, Table S8). Real-time PCR analysis of selected genes validated the microarray results (data not shown). If we compare these results to those obtained for L. pneumophila grown in vitro [65], we observed several differences. In L. pneumophila strain Paris 543 genes are upregulated in E phase. Of the genes present in both genomes 270 are only upregulated in L. pneumophila but not in L. longbeachae. The 117 genes that are upregulated in both species in exponential phase include many ribosomal proteins, the genes belonging to the ATP synthase machinery (atp genes), the NADH deshydrogenase (nuo genes), most of the genes involved in translocation systems (sec genes) and several enzymatic activities (Table S7). However, several metabolic pathways clearly induced in E phase in L. pneumophila are not induced in L. longbeachae. These include the formyl THF biosynthesis, the purine and pyrimidine and the tetrahydrofolate biosynthesis pathways. Furthermore, genes coding for several chaperones (DnaJ, DnaK or GroES), the regulatory protein RecX and several proteins related to starvation and stress are not upregulated in E phase L. longbeachae. There are only 11 genes specific for L. longbeachae and induced in E phase, all of which code proteins for which no function could be predicted.

In PE phase 313 genes are upregulated in L. longbeachae, of which only 53 are also among the 441 PE phase genes of L. pneumophila. Interestingly, 208 of the genes upregulated in PE in L. longbeachae have no orthologs in L. pneumophila, and for 70% of these no function could be predicted. Thus the response of L. longbeachae to PE phase growth is distinct from that of L. pneumophila. In particular we observed differences in the expression profiles of many factors known to be involved in L. pneumophila virulence. For example, of the genes coding putative substrates of the Dot/Icm secretion system only few, sidC (llo3098), sdhB (llo2439), sidE homologue (llo2210), sdeC/laiC (llo3092) and sdeB/laiB (llo3095) are upregulated in post-exponential phase. However, several of the newly identified putative substrates are induced in L. longbeachae in PE phase. These comprise seven proteins homologous to Sid proteins of L. pneumophila (Llo0424, Llo0426, Llo2210, Llo2439, Llo3092, Llo3095 and Llo3098), three genes coding homologues of EnhA (llo0852, llo1475 and llo2343), three ankyrin proteins (Llo0115, Llo1646 and Llo1715) and a putative serine threonine kinase (Llo1139). However, clear differences in gene expression between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae exist and the switch from replicative to transmissive phase seems to be less pronounced in L. longbeachae than in L. pneumophila. Interestingly, the genes coding the stationary phase sigma factor RpoS and the sigma factor 28 (FliA) and CsrA, all involved in the regulation of the biphasic life cycle of L. pneumophila are not differentially regulated in L. longbeachae. In contrast, seven GGDEF/EAL domain-containing regulators (llo0090, llo1253, llo1377, llo2005, llo3125, llo3392 and llo3414) and four cAMP binding proteins (llo3395, llo2387, llo2141 and llo1336) are induced in PE phase. Thus cyclic di-GMP and cAMP may be important signaling molecules for regulating PE phase traits of L. longbeachae. According to our transcriptome analysis, the switch in the lifecycle of L. longbeachae appears less pronounced as compared to L. pneumophila, and regulation may be achieved mainly by secondary messenger molecules.

Concluding remarks

L. longbeachae is the second leading cause of Legionnaires' disease in the world and a major cause of pneumonia in Australia and New Zealand. Yet, still very little is known about its virulence strategies and the genetic basis of virulence and niche adaptation. Analysis of the genome sequences of four L. longbeachae strains and its comparison with the published L. pneumophila genomes has uncovered important differences in the genetic repertoire of the two species and suggests different strategies for intracellular replication and niche adaptation.

Similar to L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae encodes a type IVB secretion system homologous to the Dot/Icm system. Inactivation of the type IV secretion system, through deletion of the dotA gene, showed that it is essential for virulence, as the dotA mutant had a severe growth defect in A. castellanii infection and could not establish an infection in the lungs of A/J mice. Despite this resemblance to L. pneumophila, the secreted effectors are very different as only 44% of the known L. pneumophila substrates were conserved in L. longbeachae. However, like L. pneumophila, many of them have eukaryotic domains or resemble eukaryotic proteins. Thus a large cohort of eukaryotic-like proteins was also a specific feature of the L. longbeachae genomes. An emerging theme in bacterial virulence is the evolution of virulence factors that can mimic the activities of Ras small GTPases (for a review see [77]). Small GTPases regulate unique biological functions of the cell as diverse as cell division/differentiation, actin cytoskeleton rearrangements, intracellular membrane trafficking. L. pneumophila produces the effector proteins RalF [78] and SidM/DrrA [40],[41] that activate small G-protein signaling cascades and interfere with host membrane trafficking. Here we identified L. longbeachae specific proteins belonging to the Rab subfamily of Ras small GTPases. These are the first prokaryotic Rab GTPases described and they may account for some of the differences in phagosome maturation between L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila. Overall, more than 3% of the L. pneumophila genome is thought to encode T4SS substrates that fulfill various functions, such as interfering with small GTPases of the early secretory pathway, disrupting phosphoinositide signaling or targeting microtubule-dependent vesicular transport. They may represent new strategies to interfere with host cell processes and may partly explain variations in the replication cycle of the two species.

An intriguing and unresolved question has been the susceptibility of C57BL/6 mice to L. longbeachae infection but their resistance to L. pneumophila infection. Only A/J mice that carry a particular Naip-5 allele are susceptible to L. pneumophila infection. Genome analysis has provided some insight into this question through the observation that L. longbeachae does not encode flagella, and thus does not trigger Naip5-dependent caspase-1 activation and subsequent proinflammatory cell death by pyroptosis [22]–[24], [59]–[62]. In contrast, L. longbeachae encodes a capsule that might be implicated in the recognition by the host immune system and which may provide some protection against killing by phagocytes. In L. pneumophila, expression of flagella is a hallmark of transmissive, virulent bacteria and a marker of its biphasic life cycle. In line with the absence of flagella, L. longbeachae also seems to have a less pronounced life cycle switch, as transcriptome analysis revealed a less dramatic change in gene expression compared to L. pneumophila. This result might explain the fact that intracellular proliferation of L. longbeachae is independent of the growth phase [11].

Previously we and others hypothesized, that L. pneumophila had acquired DNA by horizontal transfer or by convergent evolution during its co-evolution with free-living amoebae [25],[79] and that L. pneumophila uses molecular mimicry to subvert host functions [8],[80]. Presumably, L. longbeachae is not only able to interact with protozoa but also with plants, as several proteins present in plants and several enzymes which might confer the ability to degrade plant material were identified in the L. longbeachae genome.

Interestingly, the comparison of the genome sequence of four strains of L. longbeachae identified high gene content conservation unlike L. pneumophila. Furthermore, between strains of the same serogroup very few SNPs are present, most of them located in few plasticity zones, indicating recent expansion of this species. Based on these genome sequences, future comparative and functional studies will allow definition of the common and distinct survival tactics of pathogenic Legionella spp. and may open new ways to combat L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae infections.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted with approval from the University of Melbourne Animal Ethics committee application ID 0704867.3.

DNA preparation and sequencing techniques

L. longbeachae strain NSW150 was grown on BCYE agar at 37°C for 3 days and chromosomal DNA was isolated by standard protocols. Cloning, sequencing and assembly were done as described [81]. One library (inserts of 1−3 kb) was generated by random mechanical shearing of genomic DNA, followed by cloning of the fragments into pcDNA-2.1 (Invitrogen). A scaffold was obtained by end-sequencing clones from a BAC library constructed as described [82] using pIndigoBac (Epicentre) as a vector. Plasmid DNA purification was done with a TempliPhi DNA sequencing template amplification kit (Amersham Biosciences). Sequencing reactions were done with an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reactions kit and a 3730 Xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). We obtained and assembled 40299 sequences and performed finishing by adding 1125 additional sequences, as described earlier [81]. For draft genome sequencing of strains ATCC39642, 98072 and C-4E7 Illumina, shotgun libraries were generated from 5 µg of genomic DNA each using the standard Illumina protocols. Sequencing was carried out on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II as paired-end 36bp reads, following the manufacturer's protocols and with the Illumina PhiX sample used as control. Image analysis and base calling was performed by the Genome Analyser pipeline version 1.3 with default parameters.

Annotation and sequence analysis

Definition of coding sequences and annotation were done as described [81] by using CAAT-box software [83] and MAGE (Magnifying Genomes) [84]. All predicted coding sequences were examined visually. Function predictions were based on BLASTp similarity searches and on the analysis of motifs using the PFAM, Prosite and SMART databases. We identified orthologous genes by reciprocal best-match BLAST and FASTA comparisons. Pseudogenes had one or more mutations that would prevent complete translation. Analysis of the three drafts genome sequences obtained by the Illumina technique was done as follows. First, to precisely determine the average insert size of mate-paired reads, we mapped the reads of each strain to the NSW150 sequence. Then, this value was used to give good mate-pair information to the de novo assembler. Short-reads were assembled de novo into contigs (without reference to any other sequence) using Velvet (version 0.7.55) [85]. To increase specificity and length of the generated contigs, we used the hash length (k-mer) of 27. Subsequently Mauve (version 2.3.0) [86] was used to build super contigs by aligning the de novo obtained contigs on the finished NSW150 sequence. Finally, for SNP discovery the program Maq (version 0.7.1) [87] was used for mapping the Solexa reads to the NSW150 reference. To detect high confidence SNPs, we only kept those SNPs that had a coverage of 10x to 300x. SNPs with a frequency lower than 80% were removed.

Construction of a dotA mutant in strain L. longbeachae NSW150

To construct the dotA mutant strain, the chromosomal region containing the dotA gene was PCR-amplified with the primers dotA-for CTCGCGCATTGGAACTTTAT and dotA-rev TTCGCTCATAAACCGCTCTT. The product was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) yielding pGEM-dotA. We performed inverse PCR on pGEM-dotA with primers dotAinv-for CGCGGATCCCCGCATTTAATACGCCAAAC and dotAinv-rev CGCGGATCCAAGGTTTTGCGTTGGATAGG containing BamHI overhangs allowing internal deletion of 2582 bp in dotA. PCR product was digested with BamHI and ligated to the kanamycin resistance cassette, which was amplified via PCR from the plasmid pGEM-KanR, using primers containing BamHI restriction sites at the ends (Kan-BamHI-for TGCAGGTCGACTCAGAGGAT Kan-BamHI-rev CGCGGATCCGAGCTCGGTACC). Linearized vector was electroporated in L. longbeachae to obtain dotA::Km mutant.

Acanthamoeba castellanii infection assay

For in vivo growth of L. longbeachae and its dotA deletion mutant in A. castellanii we followed a protocol previously described [65]. In brief, three days old cultures of A. castellanii were washed in infection buffer (PYG 712 medium without proteose peptone, glucose, and yeast extract) and adjusted to 105–106 cells per ml. Stationary phase Legionella grown on BCYE agar, diluted in water were mixed with A. castellanii at a MOI of 0.1. After allowing invasion for 1 hour at 37°C the A. castellanii layer was washed twice with infection buffer (start point of time-course experiment). Intracellular multiplication was monitored using a 300 µl sample, which was centrifuged (14 000 rpm) and vortexed to break up amoeba. The number of colony forming units (CFU) of Legionellae was determined by plating on BCYE agar. Each infection was carried out in duplicates.

Pulmonary infection of A/J mice with L. longbeachae

The comparative virulence of L. longbeachae NSW150 and the dotA::Km derivative within A/J mice was examined via competition assays and in single infections, as described previously [21],[34]. Briefly, 6 - to 8-week-old female A/J mice (Jackson Laboratory, ME) were anesthetized and inoculated intratracheally with approximately 105 CFU of each L. longbeachae strain under investigation. At 24 and 72 h following inoculation, mice were sacrificed and their lung tissue isolated. Tissue was homogenized, and complete host cell lysis was achieved by incubation in 0.1% saponin for 15 min at 37°C. Serial dilutions of the homogenate were plated onto both plain and antibiotic-selective BCYE agar to determine the number of viable bacteria and the ratio of wild-type to mutant bacteria colonizing the lung in mixed infections.

Electron microscopy

Bacteria were transferred to Formvar-carbon-coated copper grids after glow discharged for 3′, stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 35sec, air dried and observed under a Jeol 1200EXII transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 80kV. Digital acquisition was performed with a Mega View camera and the Analysis pro software version 3,1 (ELOISE, Roissy, France).

PCR analysis

PCR for the regions containing the flagella biosynthesis coding genes in strain L. pneumophila Paris and L. longbeachae NSW150 were amplified with genomic DNA of strain Paris and NSW150 respectively. Primers were designed using the Primer 3 software to amplify a specific fragment of about 1 -3kb respectively for each region (melting temperatures 58°C). Amplification reactions were performed in a 50-µl reaction volume containing 6 ng of chromosomal DNA. The size of each PCR product was verified on agarose gels. Primers used are listed in Table S9.

Transcriptome analysis

L. longbeachae strain NSW150 was cultured in N-(2-acetamido)-2-aminoethanesulphonic acid (ACES)-buffered yeast extract broth or on ACES-buffered charcoal –yeast (BCYE) extract agar at 37C. Total RNA was extracted as previously described [88]. L. longbeachae was harvested for RNA isolation at the exponential (OD 2.5) and post-exponential phase (OD 3.7). RNA was prepared from three independent cultures and each RNA sample was hybridized twice to the microarrays (dye swap). RNA was reverse-transcribed with Superscript indirect cDNA kit (Invitrogen) and labeled with Cy5 or Cy3 (Amersham Biosciences) according to the supplier's instructions. The microarray containing 13 710 60mer oligonucleotides specific for 3567 predicted genes of the genome, the plasmid and all intergenic regions longer than 200nts has been designed using the program OligoArray (http://berry.engin.umich.edu/oligoarray/). Based on these sequences a custom oligonucleotide array was manufactured (Agilent Technologies) with a final density of 15K. For hybridization, Cy3 and Cy5 target quantities were normalized at 150 pmol. Arrays were scanned using an Axon 4000B scanner with fixed PMT (PMT = 550 for Cy3 and 650 for Cy5). Data were acquired and analyzed by Genepix Pro 5.0 (Axon Instrument). Spots were excluded from analysis in case of high local background fluorescence slide abnormalities or weak intensity. Data normalization and differential analysis were conducted using the R software (http://www.r-project.org). For each gene 3 probes were present on the microarray. Data for which at least 2 of the 3 probes gave a significant and non-contradictory result were taken into account. A loess normalization [89] was performed on a slide-by-slide basis (BioConductor package marray; http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/bioc/html/marray.html). Differential analysis was carried out separately for each comparison between two time points, using the VM method (VarMixt package [90], together with the Benjamini and Yekutieli [91] p-value adjustment method. The cut off for the expression ratio was set to either superior/equal to 2 or inferior/equal to 0.5 and the general ratio of expression of each gene was calculated as the average expression ratio from the different significant probes.

URLs

The sequence and the annotation of the L. longbeachae NSW150 genome is accessible at the LegioList Web Server (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/LegioList and http://genolist.pasteur.fr/) and under the EMBL/Genbank Accession number: FN650140 the L. longbeachae NSW150 plasmid under the EMBL/Genbank Accession number: FN650141. Due to new regulations for genome sequence submissions to EMBL/Genbank the gene names (locus_tag), which are e.g. llo0001 in the article and in the Institut Pasteur databases had to be changed to LLO_0001 in the sequence submission. According to the standards for genome sequences published by Chain and colleagues [92] the L. pneumophila NSW150 genome sequence can be defined as “Finished” and the three Solexa genome sequence drafts can be defined as “High-Quality Draft”. The complete dataset for the transcriptome analysis is available at http://genoscript.pasteur.fr in a MIAME compliance public database maintained at the Institut Pasteur and was submitted to the ArrayExpress database maintained at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/ under the Accession number: A-MEXP-1779.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. YuVL

PlouffeJF

PastorisMC

StoutJE

SchousboeM

2002 Distribution of Legionella species and serogroups isolated by culture in patients with sporadic community-acquired legionellosis: an international collaborative survey. J Infect Dis 186 127 128

2. PharesCR

WangroongsarbP

ChantraS

PaveenkitipornW

TondellaML

2007 Epidemiology of severe pneumonia caused by Legionella longbeachae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydia pneumoniae: 1-year, population-based surveillance for severe pneumonia in Thailand. Clin Infect Dis 45 e147 155

3. BibbWF

SorgRJ

ThomasonBM

HicklinMD

SteigerwaltAG

1981 Recognition of a second serogroup of Legionella longbeachae. J Clin Microbiol 14 674 677

4. CameronS

RoderD

WalkerC

FeldheimJ

1991 Epidemiological characteristics of Legionella infection in South Australia: implications for disease control. Aust N Z J Med 21 65 70

5. SteeleTW

MooreCV

SangsterN

1990 Distribution of Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 and other legionellae in potting soils in Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol 56 2984 2988

6. IsbergRR

O'ConnorTJ

HeidtmanM

2009 The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat Rev Microbiol 7 13 24

7. ShinS

RoyCR

2008 Host cell processes that influence the intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol 10 1209 1220

8. NoraT

LommaM

Gomez-ValeroL

BuchrieserC

2009 Molecular mimicry: an important virulence strategy employed by Legionella pneumophila to subvert host functions. Future Microbiol 4

9. MolofskyAB

SwansonMS

2004 Differentiate to thrive: lessons from the Legionella pneumophila life cycle. Mol Microbiol 53 29 40

10. ByrneB

SwansonMS

1998 Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect Immun 66 3029 3034

11. AsareR

Abu KwaikY

2007 Early trafficking and intracellular replication of Legionella longbeachaea within an ER-derived late endosome-like phagosome. Cell Microbiol 9 1571 1587

12. AsareR

SanticM

GobinI

DoricM

SuttlesJ

2007 Genetic susceptibility and caspase activation in mouse and human macrophages are distinct for Legionella longbeachae and L. pneumophila. Infect Immun 75 1933 1945

13. BergerKH

IsbergRR

1993 Two distinct defects in intracellular growth complemented by a single genetic locus in Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol 7 7 19

14. RoyCR

BergerKH

IsbergRR

1998 Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol 28 663 674

15. SegalG

PurcellM

ShumanHA

1998 Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 1669 1674

16. VogelJP

AndrewsHL

WongSK

IsbergRR

1998 Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science 279 873 876

17. BursteinD

ZusmanT

DegtyarE

VinerR

SegalG

2009 Genome-scale identification of Legionella pneumophila effectors using a machine learning approach. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000508 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000508

18. EnsmingerAW

IsbergRR

2009 Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm translocated substrates: a sum of parts. Curr Opin Microbiol 12 67 73

19. NinioS

RoyCR

2007 Effector proteins translocated by Legionella pneumophila: strength in numbers. Trends Microbiol 15 372 380

20. MorozovaI

QuX

ShiS

AsamaniG

GreenbergJE

2004 Comparative sequence analysis of the icm/dot genes in Legionella. Plasmid 51 127 147

21. GobinI

SusaM

BegicG

HartlandEL

DoricM

2009 Experimental Legionella longbeachae infection in intratracheally inoculated mice. J Med Microbiol 58 723 730

22. MolofskyAB

ByrneBG

WhitfieldNN

MadiganCA

FuseET

2006 Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J Exp Med 17 1093 1104

23. RenT

ZamboniDS

RoyCR

DietrichWF

VanceRE

2006 Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1 - and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog 2 e18 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020018

24. WrightEK

GoodartSA

GrowneyJD

HadinotoV

EndrizziMG

2003 Naip5 affects host susceptibility to the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Curr Biol 13 27 36

25. CazaletC

RusniokC

BruggemannH

ZidaneN

MagnierA

2004 Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat Genet 36 1165 1173

26. ChienM

MorozovaI

ShiS

ShengH

ChenJ

2004 The genomic sequence of the accidental pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science 305 1966 1968

27. SteinertM

HeunerK

BuchrieserC

Albert-WeissenbergerC

GlöcknerG

2007 Legionella pathogenicity: genome structure, regulatory networks and the host cell response. Int J Med Microbiol 297 577 587

28. DoyleRM

HeuzenroederMW

2002 A mutation in an ompR-like gene on a Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 plasmid attenuates virulence. Int J Med Microbiol 292 227 239

29. CazaletC

JarraudS

Ghavi-HelmY

KunstF

GlaserP

2008 Multigenome analysis identifies a worldwide distributed epidemic Legionella pneumophila clone that emerged within a highly diverse species. Genome Res 18 431 441

30. CianciottoNP

2009 Many substrates and functions of type II secretion: lessons learned from Legionella pneumophila. Future Microbiol 4 797 805

31. DebRoyS

DaoJ

SoderbergM

RossierO

CianciottoNP

2006 Legionella pneumophila type II secretome reveals unique exoproteins and a chitinase that promotes bacterial persistence in the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 19146 19151

32. FeldmanM

SegalG

2004 A specific genomic location within the icm/dot pathogenesis region of different Legionella species encodes functionally similar but nonhomologous virulence proteins. Infect Immun 72 4503 4511

33. FeldmanM

ZusmanT

HagagS

SegalG

2005 Coevolution between nonhomologous but functionally similar proteins and their conserved partners in the Legionella pathogenesis system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 12206 12211

34. NewtonHJ

SansomFM

DaoJ

McAlisterAD

SloanJ

2007 Sel1 repeat protein LpnE is a Legionella pneumophila virulence determinant that influences vacuolar trafficking. Infect Immun 75 5575 5585

35. NagaiH

CambronneED

KaganJC

AmorJC

KahnRA

2005 A C-terminal translocation signal required for Dot/Icm-dependent delivery of the Legionella RalF protein to host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 826 831

36. KuboriT

HyakutakeA

NagaiH

2008 Legionella translocates an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has multiple U-boxes with distinct functions. Mol Microbiol 67 1307 1319

37. ShevchukO

BatzillaC

HageleS

KuschH

EngelmannS

2009 Proteomic analysis of Legionella-containing phagosomes isolated from Dictyostelium. Int J Med Microbiol 299 489 508

38. UrwylerS

BrombacherE

HilbiH

2009 Endosomal and secretory markers of the Legionella-containing vacuole. Commun Integr Biol 2 107 109

39. UrwylerS

NyfelerY

RagazC

LeeH

MuellerLN

2009 Proteome analysis of Legionella vacuoles purified by magnetic immunoseparation reveals secretory and endosomal GTPases. Traffic 10 76 87

40. MachnerMP

IsbergRR

2006 Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev Cell 11 47 56

41. MurataT

DelpratoA

IngmundsonA

ToomreDK

LambrightDG

2006 The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat Cell Biol 8 971 977

42. WeberSS

RagazC

HilbiH

2009 The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase OCRL1 restricts intracellular growth of Legionella, localizes to the replicative vacuole and binds to the bacterial effector LpnE. Cell Microbiol 11 442 460

43. WeberSS

RagazC

ReusK

NyfelerY

HilbiH

2006 Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog 2 e46 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046

44. BrombacherE

UrwylerS

RagazC

WeberSS

KamiK

2008 The Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor SidM is a major PtdIns(4)P-binding effector protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Biol Chem 284 4846 4856

45. PanX

LührmannA

SatohA

Laskowski-ArceMA

RoyCR

2008 Ankyrin repeat proteins comprise a diverse family of bacterial type IV effectors. Science 320 1651 1654

46. EiserichJP

EstévezAG

BambergTV

YeYZ

ChumleyPH

1999 Microtubule dysfunction by posttranslational nitrotyrosination of alpha-tubulin: a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism of cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 6365 6370

47. LurinC

AndrésC

AubourgS

BellaouiM

BittonF

2004 Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16 2089 2103

48. NakamuraT

SchusterG

SugiuraM

SugitaM

2004 Chloroplast RNA-binding and pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. Biochem Soc Trans 32 571 574

49. Schmitz-LinneweberC

SmallI

2008 Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins: a socket set for organelle gene expression. Trends Plant Sci 13 663 670

50. BelyiY

StahlM

SovkovaI

KadenP

LuyB

2009 Region of elongation factor 1A1 involved in substrate recognition by Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase Lgt1: identification of Lgt1 as a retaining glucosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 284 20167 20174

51. BelyiY

TabakovaI

StahlM

AktoriesK

2008 Lgt: a family of cytotoxic glucosyltransferases produced by Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol 190 3026 3035

52. BelyiY

NiggewegR

OpitzB

VogelsgesangM

HippenstielS

2006 Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase inhibits host elongation factor 1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 16953 16958

53. HeidtmanM

ChenEJ

MoyMY

IsbergRR

2009 Large-scale identification of Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates that modulate host cell vesicle trafficking pathways. Cell Microbiol 11 230 248

54. DuchaudE

RusniokC

FrangeulL

BuchrieserC

GivaudanA

2003 The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat Biotechnol 21 1307 1313

55. HazelbauerGL

FalkeJJ

ParkinsonJS

2008 Bacterial chemoreceptors: high-performance signaling in networked arrays. Trends Biochem Sci 33 9 19

56. KrehenbrinkM

Oppermann-SanioFB

SteinbuchelA

2002 Evaluation of non-cyanobacterial genome sequences for occurrence of genes encoding proteins homologous to cyanophycin synthetase and cloning of an active cyanophycin synthetase from Acinetobacter sp. strain DSM 587. Arch Microbiol 177 371 380

57. FuserG

SteinbuchelA

2007 Analysis of genome sequences for genes of cyanophycin metabolism: identifying putative cyanophycin metabolizing prokaryotes. Macromol Biosci 7 278 296

58. de BerardinisV

DurotM

WeissenbachJ

SalanoubatM

2009 Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 as a model for metabolic system biology. Curr Opin Microbiol 12 568 576

59. DiezE

LeeSH

GauthierS

YaraghiZ

TremblayM

2003 Birc1e is the gene within the Lgn1 locus associated with resistance to Legionella pneumophila. Nat Genet 33 55 60

60. LamkanfiM

AmerA

KannegantiTD

Munoz-PlanilloR

ChenG

2007 The Nod-like receptor family member Naip5/Birc1e restricts Legionella pneumophila growth independently of caspase-1 activation. J Immunol 178 8022 8027

61. LightfieldKL

PerssonJ

BrubakerSW

WitteCE

von MoltkeJ

2008 Critical function for Naip5 in inflammasome activation by a conserved carboxy-terminal domain of flagellin. Nat Immunol 9 1171 1178

62. ZamboniDS

KobayashiKS

KohlsdorfT

OguraY

LongEM

2006 The Birc1e cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor contributes to the detection and control of Legionella pneumophila infection. Nat Immunol 7 318 325

63. KentnerD

SourjikV

2006 Spatial organization of the bacterial chemotaxis system. Curr Opin Microbiol 9 619 624

64. La ScolaB

BirtlesRJ

GreubG

HarrisonTJ

RatcliffRM

2004 Legionella drancourtii sp. nov., a strictly intracellular amoebal pathogen. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54 699 703

65. BrüggemannH

HagmanA

JulesM

SismeiroO

DilliesM

2006 Virulence strategies for infecting phagocytes deduced from the in vivo transcriptional program of Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol 8 1228 1240

66. SahrT

BruggemannH

JulesM

LommaM

Albert-WeissenbergerC

2009 Two small ncRNAs jointly govern virulence and transmission in Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol 72 741 762

67. TiadenA

SpirigT

CarranzaP

BruggemannH

RiedelK

2008 Synergistic contribution of the Legionella pneumophila lqs genes to pathogen-host interactions. J Bacteriol 190 7532 7547

68. SpirigT

TiadenA

KieferP

BuchrieserC

VorholtJA

2008 The Legionella autoinducer synthase LqsA produces an alpha-hydroxyketone signaling molecule. J Biol Chem 283 18113 18123

69. TiadenA

SpirigT

WeberSS

BrüggemannH

BosshardR

2007 The Legionella pneumophila response regulator LqsR promotes virulence as an element of the regulatory network controlled by RpoS and LetA. Cell Microbiol 9 2903 2920

70. SkerkerJM

PrasolMS

PerchukBS

BiondiEG

LaubMT

2005 Two-component signal transduction pathways regulating growth and cell cycle progression in a bacterium: a system-level analysis. PLoS Biol 3 e334 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030334

71. NewtonHJ

SansomFM

DaoJ

CazaletC

BruggemannH

2008 Significant Role for ladC in Initiation of Legionella pneumophila Infection. Infect Immun 76 3075 3085

72. LoryS

WolfgangM

LeeV

SmithR

2004 The multi-talented bacterial adenylate cyclases. Int J Med Microbiol 293 479 482

73. RasisM

SegalG

2009 The LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, together with RpoS and PmrA, post-transcriptionally regulates stationary phase activation of Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot effectors. Mol Microbiol 72 995 1010

74. Gal-MorO

SegalG

2003 Identification of CpxR as a positive regulator of icm and dot virulence genes of Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol 185 4908 4919

75. ZusmanT

AloniG

HalperinE

KotzerH

DegtyarE

2007 The response regulator PmrA is a major regulator of the icm/dot type IV secretion system in Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. Mol Microbiol 63 1508 1523

76. AltmanE

SegalG

2008 The response regulator CpxR directly regulates expression of several Legionella pneumophila icm/dot components as well as new translocated substrates. J Bacteriol 90 1985 1996

77. AltoNM

2008 Mimicking small G-proteins: an emerging theme from the bacterial virulence arsenal. Cell Microbiol 10 566 575

78. NagaiH

KaganJC

ZhuX

KahnRA

RoyCR

2002 A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science 295 679 682

79. de FelipeKS

PampouS

JovanovicOS

PericoneCD

YeSF

2005 Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J Bacteriol 187 7716 7726

80. BrüggemannH

CazaletC

BuchrieserC

2006 Adaptation of Legionella pneumophila to the host environment: role of protein secretion, effectors and eukaryotic-like proteins. Curr Opin Microbiol 9 86 94. Epub 2006 Jan 2006

81. GlaserP

FrangeulL

BuchrieserC

RusniokC

AmendA

2001 Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294 849 852

82. BuchrieserC

RusniokC

FrangeulL

CouveE

BillaultA