-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaCheating by Exploitation of Developmental Prestalk Patterning in

The cooperative developmental system of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is susceptible to exploitation by cheaters—strains that make more than their fair share of spores in chimerae. Laboratory screens in Dictyostelium have shown that the genetic potential for facultative cheating is high, and field surveys have shown that cheaters are abundant in nature, but the cheating mechanisms are largely unknown. Here we describe cheater C (chtC), a strong facultative cheater mutant that cheats by affecting prestalk differentiation. The chtC gene is developmentally regulated and its mRNA becomes stalk-enriched at the end of development. chtC mutants are defective in maintaining the prestalk cell fate as some of their prestalk cells transdifferentiate into prespore cells, but that defect does not affect gross developmental morphology or sporulation efficiency. In chimerae between wild-type and chtC mutant cells, the wild-type cells preferentially give rise to prestalk cells, and the chtC mutants increase their representation in the spore mass. Mixing chtC mutants with other cell-type proportioning mutants revealed that the cheating is directly related to the prestalk-differentiation propensity of the victim. These findings illustrate that a cheater can victimize cooperative strains by exploiting an established developmental pathway.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000854

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000854Summary

The cooperative developmental system of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is susceptible to exploitation by cheaters—strains that make more than their fair share of spores in chimerae. Laboratory screens in Dictyostelium have shown that the genetic potential for facultative cheating is high, and field surveys have shown that cheaters are abundant in nature, but the cheating mechanisms are largely unknown. Here we describe cheater C (chtC), a strong facultative cheater mutant that cheats by affecting prestalk differentiation. The chtC gene is developmentally regulated and its mRNA becomes stalk-enriched at the end of development. chtC mutants are defective in maintaining the prestalk cell fate as some of their prestalk cells transdifferentiate into prespore cells, but that defect does not affect gross developmental morphology or sporulation efficiency. In chimerae between wild-type and chtC mutant cells, the wild-type cells preferentially give rise to prestalk cells, and the chtC mutants increase their representation in the spore mass. Mixing chtC mutants with other cell-type proportioning mutants revealed that the cheating is directly related to the prestalk-differentiation propensity of the victim. These findings illustrate that a cheater can victimize cooperative strains by exploiting an established developmental pathway.

Introduction

Cooperative behaviors are susceptible to exploitation by cheaters – individuals that do not pay the full cost of cooperation, but reap the benefits [1] and thus take advantage of other cooperative individuals (victims). Cheating is predicted to affect the relative fitness of any interacting partners, especially when multiple genotypes are involved. Such behavior is thought to occur in all cooperative societies, and has been demonstrated in several different social insect colonies [2],[3], where a significant part of the population (the workers) does not take part in reproduction. In these systems, cheaters can manipulate developmental processes, thereby changing the balance between the reproductive (queen) and supporting (worker) castes. For example, cheaters exploit cooperative genotypes by tweaking mechanisms such as the regulation of organism size [3], developmental timing [2] and differentiation into different castes [3],[4]. It is likely that the regulation of other developmental processes – cell-division and cell-fate determination, proportioning and maintenance – is also susceptible to cheating. However, it is hard to study these mechanisms at the genetic and cellular levels due to the complex nature of these social systems.

Social microorganisms are good model systems for the study of cheating mechanisms at the molecular level. The social amoebae Dictyostelium discoideum provide an added advantage because the cells exhibit social behavior in the context of multicellular development. Dictyostelium cells propagate as unicellular amoebae and feed on bacteria. However, under conditions of starvation, about 105 cells aggregate and go through multicellular development. The cells give rise to a structure called the fruiting body where 70–80% of the cells form viable spores that may germinate in the next generation to form amoebae, while the remaining cells give rise to dead, vacuolated cells that contribute to stalk-formation and hence sacrifice their reproduction [5].

This developmental cycle is different from the development of metazoan organisms, since multicellularity is achieved by aggregation rather than by cell division of a fertilized egg. An important consequence is that Dictyostelids readily form organisms containing multiple clones. In such chimerae, different genotypes can contribute differently to the production of the reproductive (spores) and supporting (stalk cells) cell-types, and change their representation in subsequent generations, similar to the cheating behavior seen in insect societies. Disproportionate over-representation of a specific genotype in the spore population of a chimeric fruiting body at the cost of another strain is defined as cheating, and the over - and under-represented strains are termed as ‘cheaters’ and ‘victims’, respectively. Chimerism has been observed in nature [6], and clones isolated from the wild can cheat on one another in the laboratory [7].

The first cheater mutant identified in D. discoideum, chtA (fbxA), is an obligate parasite that is unable to form spores in clonal populations [8]. When mixed with chtA, the wild-type prespore cells differentiate into stalk cells. This is the only cheating mechanism that has been identified in Dictyostelium to date. However, since chtA does not complete development under clonal conditions, it is unlikely that its behavior is characteristic of cells in the wild since Dictyostelium strains are often found in clonal populations [6].

Recent studies have shown that a large number of mutations in Dictyostelium can lead to facultative cheating [9]. Facultative cheater mutants are capable of forming fruiting bodies in clonal populations, but cheat on wild-type cells in chimera. These mutants probably cheat by exploiting a variety of mechanisms, and the social genes identified are predicted to be involved in a variety of different cellular processes [9]. Development in Dictyostelium involves both the initial differentiation and proportioning of several different cell-types, and the subsequent maintenance of cell-fate and cell-type proportions. Any of these developmental mechanisms might be co-opted by selfish cheater mutants, akin to what is seen in insect societies. Consequently, the study of such cheater mutants is likely to facilitate greater understanding of specific pathways of differentiation in Dictyostelium, in addition to developmental cheating mechanisms in general.

We have studied chtC [10], one of the strongest facultative cheater mutants identified by Santorelli et al. [9]. We found that chtC has defects in maintaining the prestalk cell fate, and consequently is defective in the expression of certain late prestalk markers. Even though this does not lead to any discernible stalk defects when chtC mutants develop on their own, wild-type cells increase their prestalk differentiation in chimerae with chtC and are cheated upon. These findings suggest that cheaters in Dictyostelium can manipulate mechanisms of developmental regulation such as the maintenance of cell-type proportioning to take advantage of other strains in the population, while retaining their fitness under clonal conditions.

Results

The chtC gene

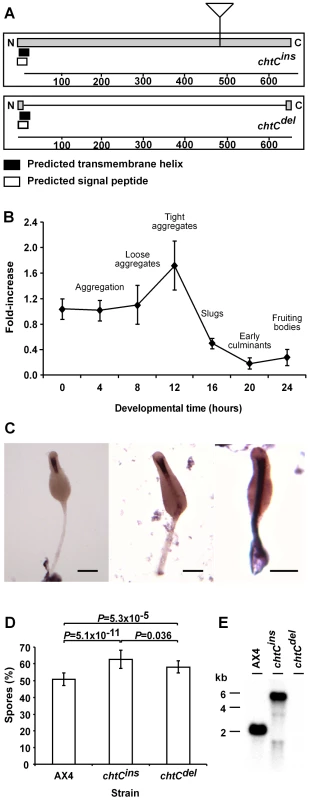

LAS5 was one of the strongest cheater strains identified in a large scale screen for cheater mutants [9]. This mutant strain has a plasmid insertion in the chtC gene [10]. The chtC gene is predicted to encode an approximately 75 kDa protein with a signal peptide anchor and a transmembrane domain at the N-terminus (Figure 1A). This protein has orthologs of unknown function with about 20% identity in ciliates such as Paramecium tetraurelia and Tetrahymena thermophila, but no detectable homology to proteins in other organisms (data not shown). The gene is also up-regulated in AX2 cells incubated with E. coli when compared to cells incubated in axenic medium [11]. To determine the expression properties of the chtC transcript, we collected RNA from AX4 cells at 4-hour intervals throughout development and performed quantitative reverse transcription PCR (Q-RT-PCR) with chtC-specific primers (Figure 1B). We found chtC mRNA at all times with a peak at 12 hours of development, when the cells were at the tight aggregate stage, followed by a decline at 16 hours and comparatively lower levels thereafter. We also tested the spatial expression pattern of chtC by whole mount in situ RNA hybridization. The chtC mRNA was uniformly abundant in all cells during the finger stage of development (data not shown), but became highly enriched in the stalk, with the highest levels in the funnel (Figure 1C), which is at the top of the stalk tube, during late culmination (fruiting body formation).

Fig. 1. The chtC gene.

(A) chtC encodes a putative transmembrane protein with a signal sequence and a single N-terminal transmembrane domain. The chtCins mutant strain carries an insertion of the pLPBLP plasmid in the chtC ORF. In the chtCdel mutant, most of the chtC ORF has been replaced by the pLPBLP plasmid. (B) Quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR with primers specific to chtC performed on RNA samples collected from wild-type AX4 cells at 4-hr intervals during development as indicated on the x-axis. Data are presented as the fold change relative to the levels at 0 hrs (y-axis) and are the averages and standard errors of 3 measurements each of 2 independent biological replications. The developmental stages corresponding to the different time-points are indicated. (C) in situ RNA hybridization with a probe against chtC on whole-mount late culminant structures (22–24 hours of development). Staining is enriched in the stalk and specifically in the funnel (the upper part of the stalk). The scale bar represents 0.1 mm. (D) Spore production of the wild type (AX4) and the two mutants (chtCins and chtCdel) when mixed in a 1∶1 ratio with AX4-GFP cells and developed as chimerae. The data are presented as the proportion (%) of the spores produced by the strain of interest relative to the total spores produced by the chimerae. The results are the means and standard errors of at least 8 independent replications. The chtC mutants form significantly more spores compared to AX4 (Student's t-test) and the chtCins mutant cheats significantly more than the chtCdel mutant (Student's t-test). The P-values for each pair (corrected for multiple testing using the ‘Benjamini and Hochberg’ method) are shown above the respective bars. (E) Northern blot analysis, with a probe against chtC, of total RNA prepared from 8-hr cells. The genotypes are indicated above the lanes and the molecular weights (kilobase) are indicated on the left. Different alleles of chtC lead to cheating

The original mutant, LAS5, had a pBSR1 plasmid insertion at nucleotide 1377 of the chtC ORF (Figure 1A). We generated two new alleles of chtC. The chtCins mutant contains a plasmid insertion at position 1377 of the endogenous locus and the chtCdel mutant contains a plasmid instead of the endogenous region that codes for amino acid 13 – 642 (Figure 1A). Both strains were made sensitive to Blasticidin S to facilitate the analysis of chimerae. The alleles were confirmed by Southern blot analysis and by PCR across the relevant insertion sites (data not shown).

We first tested the spore-forming ability of the chtC mutants. Sporulation of the clonal chtC mutants and of 1∶1 chimerae between the chtC mutants and AX4, were indistinguishable from that of clonal AX4 populations, as tested by determining spore morphology (data not shown), sporulation efficiency, resistance to detergent, and germination efficiency (Figure S1). This finding is in contrast to the original LAS5 mutant which had a higher sporulation efficiency compared to AX4 cells [9], suggesting that different alleles of chtC can lead to distinct phenotypes. We then studied the behavior of the chtC mutants in chimera. We first tested whether the chtC mutants co-aggregate with wild-type cells by observing 1∶1 mixtures of either chtCins or chtCdel with AX4 at 8 hours of development (Figure S2). Both the chtC mutants co-aggregated with AX4 cells, similar to an AX4 control. We then tested the cheating behavior of the chtC mutants by mixing either chtCins or chtCdel at a 1∶1 ratio with AX4/[act15]:GFP (AX4-GFP) cells and letting the mixed populations complete development to form fruiting bodies. We also mixed AX4-GFP cells with unlabeled AX4 cells as a control. Following development, we collected all the cells, selected for spores by detergent treatment, and counted the ratio of fluorescent to non-fluorescent spores. In the control mixes we found that the AX4 cells form approximately 50% of the spores, suggesting that the AX4-GFP strain behaves in an almost identical fashion to AX4 (Figure 1D). Both the chtCins and the chtCdel mutants cheated - they formed a significantly higher number of spores than AX4 (Figure 1D). Further, the chtCins mutant cheated significantly more than the chtCdel mutant did, suggesting that the chtCins mutant is not a null mutant. We then tested the two mutants by developing them in a 1∶1 mixture with each other. The chtCins mutant cheated on the chtCdel mutant by forming 60.7%±5.7% spores, which is significantly greater than the hypothesized value of 50% (n = 3, one-sample one-sided t-test, P = 0.041).

Thus the chtCins mutant is distinct from the chtCdel mutant, suggesting that it is not a null, but possibly a gain-of-function allele. In order to test this possibility further, we performed Northern blot analysis with a chtC probe on 8-hour RNA samples from AX4 and from the chtCins and chtCdel mutants (Figure 1E). The wild type chtC transcript size is 2 kb, as expected from the predicted gene model. The chtCdel mutant does not express detectable levels of the transcript, consistent with the deletion of nearly the entire gene and confirming the hypothesis that it is a null-mutant. The chtCins strain expresses a 5–6 kb transcript. Northern blot analysis with a probe against the inserted plasmid showed that this was due to read-through transcription into the plasmid insertion (data not shown). We also performed RT-PCR with primers against the region of the chtC gene downstream of the insertion and observed a product (data not shown). These data suggest that the chtCins mutant expresses an aberrant transcript that extends across the inserted plasmid and back into the chtC gene.

The chtC mutants are defective in maintaining the prestalk cell fate

The cheating behavior of the mutant strains and the stalk-enriched expression of the chtC mRNA during late developmental stages suggested that chtC may play a role in stalk development although the ubiquitous expression of the gene at earlier stages may imply a role in prespore cells or spores as well. Nevertheless, the chtC mutant strains appear morphologically indistinguishable from the parental AX4 strain during growth and development, (Figure S1 and data not shown). We therefore tested other stalk phenotypes of the chtC mutants. During development of wild-type D discoideum, the small molecule DIF-1 (Differentiation Inducing Factor-1) induces the differentiation of stalk cells, and inhibits spore-differentiation, and sensitivity to this molecule is important for the differentiation of a specific sub-type of prestalk cells. After differentiation, prestalk cells are localized in the anterior part of a developing slug, where they are required for proper slug migration. Finally, wild-type fruiting bodies in D. discoideum contain stalks that consist of vacuolated cells and cellulose deposits, which are important for the formation of a properly structured stalk [5]. We tested each of these stalk phenotypes in the chtC mutants by examining squashes of culminants (fruiting bodies) using high-power phase-contrast microscopy, staining for cellulose with the fluorescent dye calcofluor [12], testing for DIF-1 sensitivity by the cAMP-removal and 8-Br-cAMP monolayer assays [13], and testing slug migration. We found no significant difference between AX4 and the chtC mutants in these assays (data not shown).

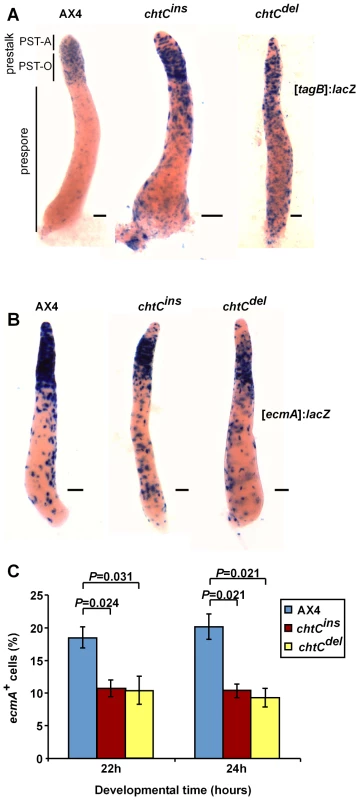

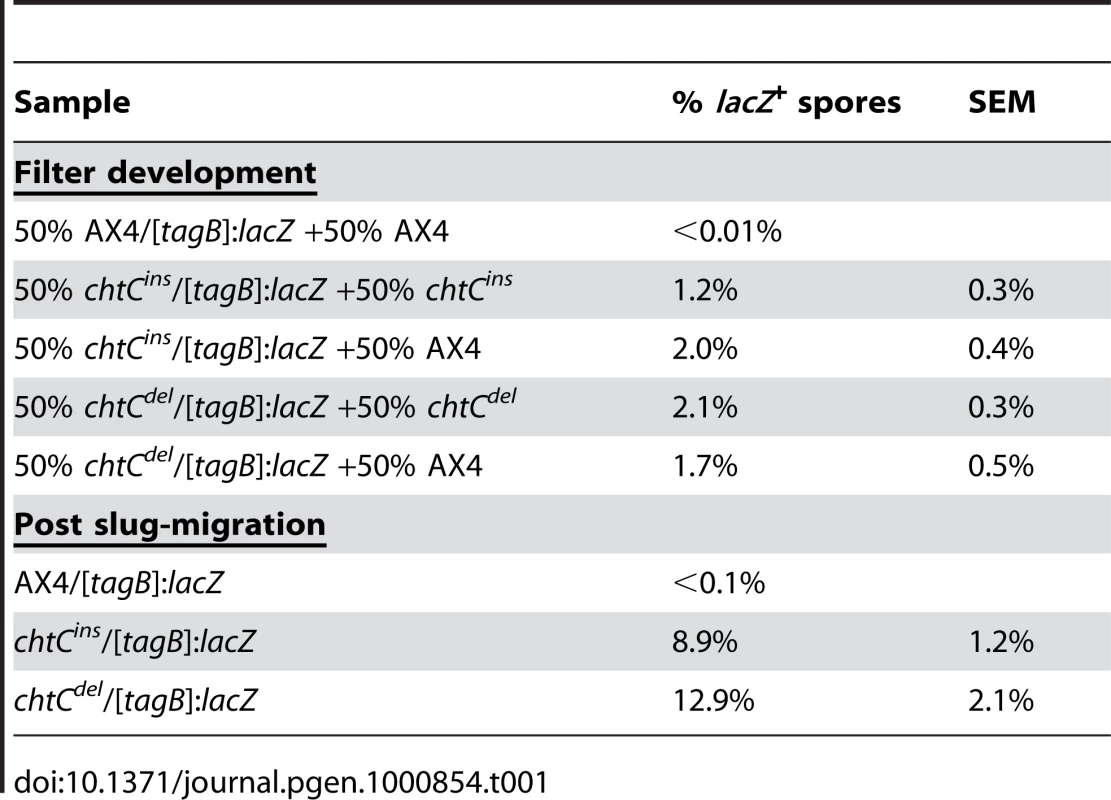

To study stalk differentiation in greater detail, we used 2 different prestalk markers – tagB and ecmA. Expression of the tagB gene is induced 8 hours into development in prestalk cells, about 4 hours earlier than ecmA [14]. Also, unlike ecmA, expression of the tagB gene is not induced by DIF-1 [15]. We developed [tagB]:lacZ labeled strains of both the chtCins and chtCdel mutants, and stained for β-galactosidase activity. In AX4 cells, tagB is expressed in the entire prestalk region [14]. Both the chtCins and chtCdel mutants showed strong staining in the posterior half of the prestalk region (the prestalk-O or PST-O region [16]), and weaker staining in the anterior half (the prestalk-A or PST-A region). There was also significant staining in the prespore region, suggesting that some prespore cells express the tagB marker or have expressed it prior to becoming prespore cells (Figure 2A). In order to test this possibility, we examined the spores made by chtC mutants labeled with the [tagB]:lacZ marker. We found a 100-fold increase in the proportion of tagB-positive spores formed by either of the chtC mutants, compared to AX4 (Table 1).

Fig. 2. The chtC mutants exhibit prestalk defects.

AX4, chtCins and chtCdel strains labeled with either [tagB]:lacZ (A) or [ecmA]:lacZ (B) were developed for 16 hours, fixed and stained with X-gal. In both cases, 20% of the cells were labeled and the remaining population consisted of the unlabeled parental strain. Representative slugs for each strain are shown. The scale bars represent 0.1 mm. The different parts of the slug are shown in (A). (C) Multicellular structures of AX4, chtCins and chtCdel were dissociated after 22 and 24 hours of development, fixed and stained with X-gal, and the number of blue cells was determined. The data are shown as the proportion (%) of stained cells relative to the entire population. The results are the means and standard errors of at least 3 independent replications. Brackets above the respective bars indicate that the chtCins and the chtCdel mutants have significantly fewer stained cells as compared to AX4 (Student's t-test). Individual P-values (corrected for multiple testing by the ‘Benjamini and Hochberg’ method) are indicated above the bars. Tab. 1. <i>chtC</i> spores have a prestalk history.

The deficit of [tagB]:lacZ-expressing cells in the PST-A region, combined with the increase in prespore cells that express [tagB]:lacZ suggests that the tagB-expressing prestalk cells, which contribute to the PST-A region in the wild type, are undergoing transdifferentiation and form spores instead of stalk cells. An increase in this transdifferentiation in the presence of AX4 cells would be a potential mechanism of cheating. However, we observed no significant change in the proportion of [tagB]:lacZ-positive spores when the chtC mutants were mixed with unlabeled AX4 instead of the unlabeled chtC mutant cells (Table 1).

Prolonged migration of Dictyostelium slugs results in increased transdifferentiation of prestalk cells into spores [17],[18]. To test whether the chtC mutants showed increased transdifferentiation under such conditions, we allowed the [tagB]:lacZ labeled chtC mutants to migrate for 48 hours, and then induced culmination. We collected spores, stained them with X-gal, and counted the number of stained spores (Table 1). In the chtC mutant strains, 8–12% of the spores were labeled, suggesting that they had a prestalk history. Thus, a significant proportion of the chtC mutant population undergoes a cell-fate transformation, suggesting that the chtC gene is required for the maintenance of the prestalk cell fate.

In order to further dissect the prestalk properties of the chtC mutants, we generated chtC mutant strains expressing lacZ under the prestalk promoter, ecmA. We developed these strains, and stained for β-galactosidase activity. Both the chtCins and chtCdel mutants showed strong staining in the PST-O region, but weaker staining in the PST-A region (Figure 2B), similar to the phenotype seen in the [tagB]:lacZ strains, suggesting that in the chtC mutants, the cells in the PST-A region are defective in both tagB as well as ecmA expression. However, there was no discernible change in the expression of ecmA in the prespore region, compared to AX4. We quantified this phenotype by dissociating the structures during late culmination and counting the number of cells that stained positively for β-galactosidase activity. Both the chtC mutants formed significantly fewer ecmA positive cells than AX4 (Figure 2C). There was no significant change in the proportion of ecmA positive cells when the labeled chtC strains were mixed with either the unlabeled parent or unlabeled AX4 (data not shown).

To determine the timing of transdifferentiation, we determined the proportion of ecmA-positive spores formed by the chtC mutants using the [ecmA]:lacZ labeled strains. We found no significant difference compared to AX4 [ecmA]:lacZ cells (data not shown). This finding suggests that in the chtC mutants, a population of prestalk cells that would otherwise have given rise to PST-A cells changes its cell fate and goes on to form spores instead. This process takes place soon after the initial prestalk-cell differentiation - after the induction of tagB expression, but before ecmA induction, a timing that coincides with the peak in chtC mRNA levels (Figure 1B). We further investigated this process by comparing tagB expression levels in 16 h slugs and in fully differentiated spores in both the chtC mutants and in the parental wild type cells (Figure S3). The level of tagB mRNA was significantly lower in the spores at 24 h as compared to the level in slugs at 16 h, suggesting that the tagB expression observed in the spores of the chtC mutants is not due to a wholesale induction of tagB expression in prespore cells but rather to a transdifferentiation of a small proportion of the prestalk cells. Even though the chtCins mutant had higher levels of tagB expression at 16 h of development (compared to AX4), the level of tagB mRNA in the spores for both the chtC mutants was not significantly increased compared to a similar AX4 control. These data further support the conclusion that the blue staining observed in spores of the [tagB]:lacZ labeled chtC-mutants reflects transdifferentiation of prestalk cells into prespore cells.

Interestingly, even though the PST-A region in the chtC mutant slugs is defective for the expression of two separate markers – tagB and ecmA – the chtC mutants have no overt defects in stalk morphology or function, suggesting that under laboratory conditions, the expression of these markers is not required for proper PST-A cell function.

We also tested whether the chtC gene was required to maintain the prespore cell fate, by observing slugs of either AX4, chtCins or chtCdel expressing the [cotB]:lacZ marker (cotB is a well-established prespore marker that is expressed exclusively in prespore cells and spores) [19]. Neither mutant strain expressed the cotB marker in the prestalk region (Figure S4), suggesting that the chtC mutant cells are not undergoing transdifferentiation from prespore to prestalk cells and that the directional transdifferentiation we observe is not due to a general defect in cell type differentiation.

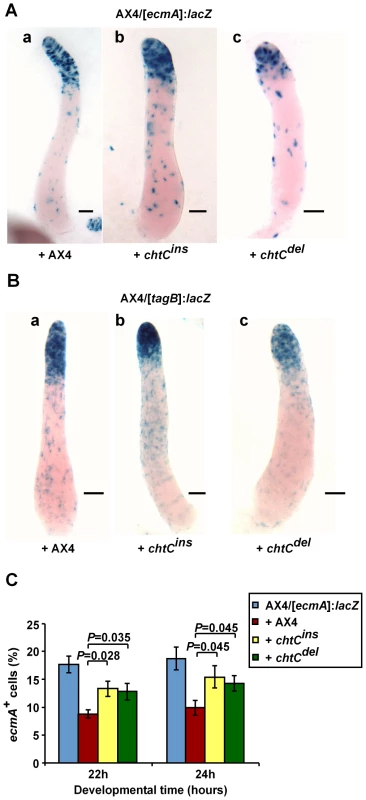

The chtC mutants increase prestalk differentiation of wild-type cells in chimerae

The chtC mutants are defective in the maintenance of the prestalk cell-fate. We hypothesized that this defect in chtC cells would affect prestalk differentiation of AX4 cells in chimera. In order to test this hypothesis, we examined the pattern of AX4 prestalk cells in chimeric populations. We developed mixed populations of 20% AX4/[ecmA]:lacZ cells and 80% unlabeled chtC cells. When mixed with either the chtCins or the chtCdel mutant, the AX4/[ecmA]:lacZ cells were preferentially localized in the PST-A region (Figure 3A). We repeated the experiment using the AX4/[tagB]:lacZ strain [15], and found similar results (Figure 3B). These experiments were also carried out at a 1∶1 ratio between AX4 cells and the chtC mutants, and qualitatively similar results were observed (data not shown), though the effects were more pronounced at a 1∶4 ratio.

Fig. 3. The chtC mutants affect prestalk development of AX4 in chimerae.

Strains were grown clonally and then mixed at the appropriate proportions and developed in chimerae. AX4 cells labeled with either [ecmA]:lacZ (A) or [tagB]:lacZ (B) were mixed in a 1∶4 ratio with unlabeled AX4, chtCins or chtCdel cells as indicated. Multicellular structures were fixed and stained with X-gal after 16 hours of development. Representative slugs for each chimeric mixture are shown. The scale bars represent 0.1 mm. (C) AX4/[ecmA]:lacZ cells were developed either clonally, or in a 1∶1 mix with unlabeled AX4, chtCins or chtCdel cells. Multicellular structures at 22 h and 24 h of development were dissociated, the cells were stained with X-gal and the number of blue cells was determined. The data are shown as the proportion (%) of stained cells relative to the entire population. The results are the means and standard errors of 6 independent replications. The number of stained AX4 prestalk cells is significantly increased in the presence of the chtC mutants, compared to AX4 (Student's t-test). Individual P-values (corrected for multiple testing by the ‘Benjamini and Hochberg’ method) are indicated above the bars. To quantify this finding, we mixed AX4/[ecmA]:lacZ cells with each of the chtC mutants, and developed them in chimera. We collected samples at 22 and 24 hours, dissociated the structures and counted the number of cells that stained positive for β-galactosidase activity. The presence of either of the two chtC mutants caused an increase in the number of ecmA positive cells in AX4 (Figure 3C), suggesting that the chtC mutants may cheat by causing an increase in the proportion of AX4 prestalk cells.

A simple explanation of these results is that in chimera, a defect in prestalk differentiation in the PST-A region of the chtC mutants is compensated for by AX4 cells, which then occupy the PST-A region to fill the void, and differentiate into more prestalk cells. As such chimeric mixtures complete development, AX4 cells thus form a smaller proportion of spores compared to the chtC mutants, and get cheated upon. In clonal chtC populations, in spite of the defective prestalk marker expression, cells of the chtC mutants take on the PST-A cell-fate and are able to form morphologically normal fruiting bodies, with similar numbers of spores compared to clonal AX4 populations.

The chtC mutants have divergent effects on other mutants that affect prestalk cells

The model proposed above predicts that the ability of the victim to contribute to the PST-A region is important for the cheating mechanism of the chtC mutants. If the model were correct, the cheating phenotype of the chtC mutants would be correlated with the ability of their chimeric counterparts to contribute to the PST-A region, and consequently differentiate an increased number of prestalk cells. In order to test this prediction, we mixed the chtC mutants with two other mutants that avoid the PST-A region in chimera with AX4 cells, the tagA– and tagB– mutants, and examined prestalk differentiation and spore production.

The tagA– mutant

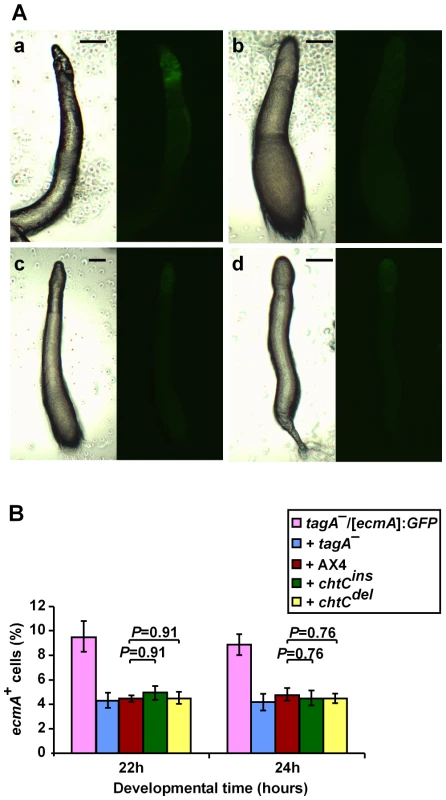

The tagA– and the tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP strains were described previously [20],[21]. The tagA– mutant has defects in cell-type specification, and does not contribute to the PST-A region and to the terminal stalk structure in chimera with AX4 cells. We examined the patterning of the tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP cells at the slug stage of development. As expected, the tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP cells showed a wild-type like pattern of fluorescence in the anterior part of the slug when developed as a clonal population (data not shown) and in 1∶1 mixtures with the unmarked tagA– strain (Figure 4A a). In chimerae with AX4, the tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP cells showed almost no fluorescence in the prestalk region, consistent with the published observations [20] (Figure 4A b). The results of mixing the tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP cells with either one of the chtC mutants were nearly indistinguishable from that seen when mixing tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP with the wild type (Figure 4A c,d).

Fig. 4. The tagA– mutant is unaffected by the presence of chtC mutants in chimerae.

The strains were grown separately and mixed in the appropriate proportions before development in chimera. (A) We photographed multicellular structures after 16 hours of development under phase-contrast microscopy (left panels) and fluorescence microscopy (right panels). The tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP strain was mixed in a 1∶1 ratio with unlabeled tagA– cells (a), unlabeled AX4 cells (b), unlabeled chtCins cells (c), and unlabeled chtCdel cells (d). The entire prestalk region (shown by white arrows) is fluorescently labeled in a, but very little fluorescence in seen in b-d. Representative slugs for each chimeric mixture are shown. The scale bars represent 0.1 mm. (B) The tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP strain was developed either clonally or in a 1∶1 mix with unlabeled tagA–, AX4, chtCins, or chtCdel cells. We disaggregated the cells after 22 h and 24 h of development, and determined the proportion of GFP-positive cells by counting under the fluorescence microscope. The data are shown as the proportion (%) of fluorescent cells relative to the entire population. The results are the means and standard errors of 3 independent replications. The number of prestalk cells formed by the tagA– mutant is not significantly different in the presence of the chtC mutants, as compared to AX4 (Student's t-test). Individual P-values (corrected for multiple testing by the ‘Benjamini and Hochberg’ method) are indicated above the bars. Since the tagA– prestalk cells do not appear to occupy the PST-A region in chimera with the chtC mutants, we predicted that the proportion of tagA– prestalk cells would also be unaffected in chimerae with chtC. To test this prediction, we mixed tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP cells with either of the chtC mutants in a 1∶1 ratio, developed them and counted the proportion of fluorescently labeled cells after 22 and 24 hours of development. Neither the chtCins nor the chtCdel mutant affected the proportion of [ecmA]:GFP positive cells formed by the tagA– mutant (Figure 4B). Thus the tagA– mutant appears unaffected by the presence of the chtC mutants in chimera, unlike the phenotype seen in the case of wild-type cells (though it is possible that the lower sensitivity of detection of the GFP reporter as compared to β-galactosidase may be preventing the observation of subtle effects). According to our model, these data would suggest that the chtC mutants should not be able to cheat on the tagA– mutant.

The tagB– mutant

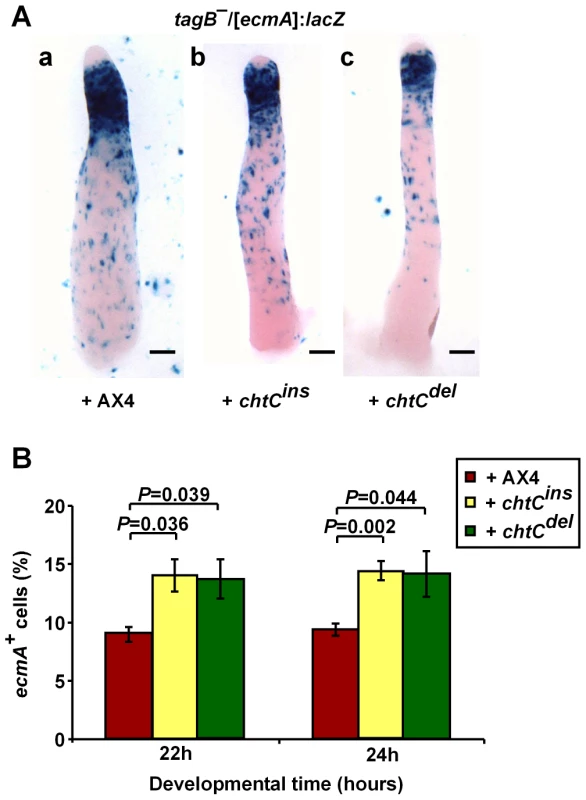

We performed similar experiments with the tagB– and tagB–/[ecmA]:lacZ strains [14]. The tagB– mutant is unable to proceed beyond the tight aggregate stage of development in a clonal population. However, in chimera with AX4, tagB– cells can proceed through development, but do not contribute to the PST-A region or to the stalk. We studied the patterning of the tagB–/[ecmA]:lacZ cells at the slug stage of development. As expected, the tagB–/[ecmA]:lacZ cells occupy the PST-O zone when mixed with AX4 cells at a 1∶4 ratio, leaving a substantial portion of the tip (PST-A region) unstained (Figure 5A a). However, in 1∶4 chimerae with the chtC mutants, the tagB– prestalk cells were considerably anteriorized, and occupied a larger portion of the PST-A zone (Figure 5A b,c). Similar results were seen at a 1∶1 ratio between the tagB– cells and the chtC-mutants (data not shown), though the phenotype was more pronounced in the 1∶4 chimerae. Based on this observation, our model predicts that the tagB– mutant would differentiate more prestalk cells in chimerae with the chtC mutants. We tested this prediction and observed that in chimerae with the chtC mutants, the tagB–/[ecmA]:lacZ strain produced a higher proportion of [ecmA]:lacZ positive prestalk cells (Figure 5B), similar to the phenotype seen when AX4 is mixed with the chtC mutants.

Fig. 5. The tagB– mutant behaves like AX4 in chimerae with the chtC mutants.

The strains were grown separately and mixed in the appropriate proportions before development in chimera. (A) Developing structures were fixed and stained after 16 h of development. The tagB–/[ecmA]:lacZ strain was mixed in a 1∶4 ratio with unlabeled AX4 cells (a), unlabeled chtCins cells (b), and unlabeled chtCdel cells (c). Representative slugs for each chimeric mixture are shown. The scale bars represent 0.1 mm. (B) The tagB–/[ecmA]:lacZ strain was developed either clonally or in a 1∶1 mix with unlabeled AX4, chtCins or chtCdel cells. We disaggregated the cells after 22 or 24 h of development, stained with X-gal and determined the number of blue cells. The data are shown as the proportion (%) of stained cells relative to the entire population. The results are the means and standard errors of at least 4 independent replications. The number of stained prestalk cells formed by the tagB– mutant is significantly increased in the presence of the chtC mutants, as compared to AX4 (Student's t-test). Individual P-values (corrected for multiple testing by the ‘Benjamini and Hochberg’ method) are indicated above the bars. Thus, the tagB– mutant cells behave like the wild type AX4 cells in chimerae with the chtC mutants, suggesting that the chtC mutants would cheat on tagB– cells.

Cheating by the chtC mutants is correlated with the effect on prestalk differentiation

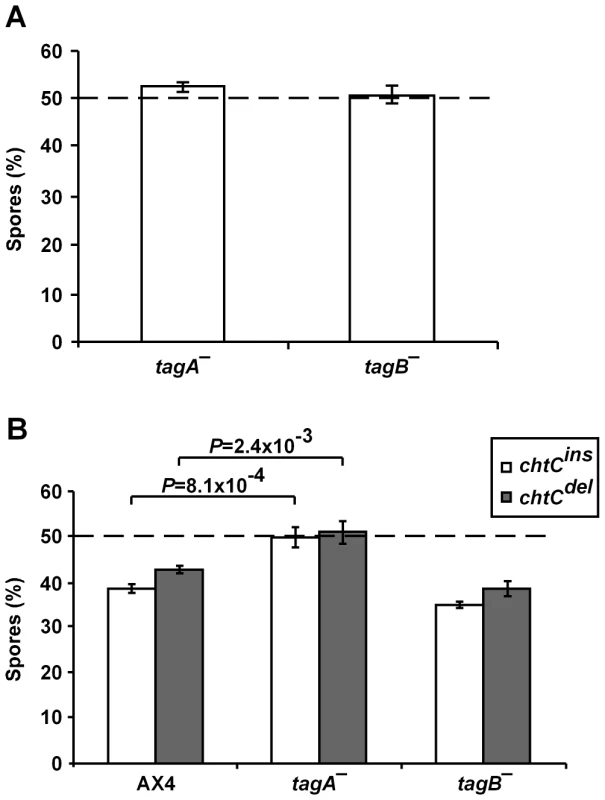

We first tested the spore production of the tagA– and tagB– mutants in control chimerae with the wild type AX4. We grew the strains clonally, mixed each strain at a 1∶1 ratio with AX4 cells and allowed the chimerae to develop. We determined the ratio of spores formed by each strain after development (Figure 6A). In terms of cheating, both the tagA– and the tagB– mutants were neutral when compared to AX4, each forming approximately 50% of the spores in the 1∶1 mix.

Fig. 6. The chtC mutants cheat on tagB–, but not on tagA–.

The strains were grown separately and mixed in the appropriate proportions before development in chimera. (A) Spore production of the tagA– and tagB– mutants when mixed in a 1∶1 ratio with AX4-GFP cells. The data are presented as the proportion (%) of the spores produced by the strain of interest relative to the total spores produced by the chimerae. The results are the means and standard errors of at least 3 independent replications. Both the tagA– and tagB– mutants form approximately 50% of the spores, showing that they are neutral in terms of cheating behavior. (B) Spore production of AX4-GFP, tagA– and tagB– when mixed in a 1∶1 ratio with chtCins and chtCdel cells. The data are presented as the proportion (%) of the spores produced by the strain of interest relative to the total spores produced by the chimerae. The results are the means and standard errors of at least 3 independent replications. In the chimerae with either chtC mutant, the tagA– mutant forms significantly more spores and the tagB– mutant is not significantly different, compared to AX4 (Student's t-test). Individual P-values are indicated above the bars for the significantly different strains. We then performed mixing experiments between the chtC mutants and either the tagA– or the tagB– mutants (Figure 6B). We found that neither chtCins nor chtCdel cheated on the tagA– mutant, but both cheated on the tagB– mutant. These results correlate well with the effects of the chtC mutants on the prestalk differentiation of the tagA–and the tagB– mutants in chimerae with chtC, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Discussion

This study describes the first analysis of a facultative cheater mutant in Dictyostelium. Mutants that lack chtC gene function sporulate normally in clonal populations, but cheat on wild-type cells in chimerae. The two mutant alleles we have generated, chtCins and chtCdel, share most but not all of their cheating phenotypes. The chtCins mutant is a “stronger” cheater since it cheats at a higher proportion on AX4, and cheats on the chtCdel mutant. It is also a slightly better cheater when mixed with either tagA– or tagB–. The chtCdel allele is a loss-of-function allele, by definition. Therefore, based on the phenotypic differences between the two mutant alleles, and due to the expression of a fusion transcript in the chtCins mutant, we propose that the insertion generated a gain-of-function allele. One possibility is that the neomorphic chtCins allele impairs the functioning of other proteins in the pathway, via aberrant interactions. However, our data do not provide any molecular insight into this phenomenon.

The chtC gene is required for maintenance of the prestalk cell fate

The chtC mutants undergo a transformation of cell-fate, since cells with a prestalk history form spores. This is coincident with a PST-A specific defect in the expression of prestalk markers such as tagB and ecmA, suggesting that cells fated to occupy the PST-A region transdifferentiate and form spores instead. Thus the chtC gene appears to be involved in the maintenance of the PST-A cell-fate. This idea is also supported by the cell-type specificity of chtC gene expression, since during late development, chtC is the most stalk-enriched gene described to date, being expressed predominantly in the stalk, and not in other prestalk-derived tissues like the upper and lower cups. Thus, chtC is one of the few genes identified to be involved in maintaining cell-fate [21]–[23]. It is interesting to note that despite the defects in maintenance of the prestalk cell-fate and expression of prestalk markers, stalk morphology and function in the chtC mutants appears indistinguishable from that of the wild type.

This finding raises the question of why the chtC mutants have not spread within the population, and why the chtC gene still exists in the genome in Dictyostelium. It is possible that the chtC mutants have fitness defects in growth or development in the wild, or under specific environmental conditions that we have not explored in the laboratory. Additionally, it has been shown that mutants that can resist cheating by the chtCins mutant can be selected for in a population containing the chtCins mutant [10]. Such cheater-resistors can even inhibit the cheating by the chtC mutants, and may thus help to maintain the chtC gene in the population [10].

Void in prestalk differentiation in the chtC mutants likely leads to cheating

The chtC mutants differentiate a population of cells that express prestalk markers, but adopt the prespore cell-fate. This transdifferentiation is associated with a decrease in the number of cells that express the late prestalk marker ecmA. In chimerae between AX4 and chtC cells, the AX4 cells differentiate a higher number of ecmA-positive cells. The simplest explanation for these observations is that the void in prestalk cells in chtC is detected by the AX4 cells, which then compensate by differentiating more prestalk cells.

The proportions between prestalk and prespore cells are almost constant in Dictyostelium slugs over a wide range of total cell numbers, indicating that well-regulated proportioning mechanisms control the initial differentiation of prestalk and prespore cells [24]. Our data support the hypothesis that there is a feedback mechanism that helps to sense the proportions of properly differentiated prestalk cells, and regulates the differentiation of as yet undifferentiated cells into the required cell-types as development proceeds.

Prestalk patterning is important for cheating by the chtC mutants

The presence of the chtC mutants in chimerae affects the prestalk differentiation and patterning of the wild-type cells, which is likely to be the direct mechanism of cheating. In order to test whether prestalk patterning was important for cheating, we utilized two other prestalk differentiation mutants - tagA– and tagB–. In both cases, the ability of the chtC cells to affect patterning was directly correlated to the cheating behavior, suggesting that the patterning was indeed important for cheating. Nevertheless, the ability to cause wild-type cells to occupy the PST-A zone in chimera does not necessarily equate to cheating, since neither tagA– nor tagB– are cheaters. In chimerae, tagA– mutants also cause wild-type cells to occupy the PST-A region and to be the sole contributor of stalk cells [20], but the tagA– mutants are not cheaters. This finding suggests that the mechanism of cheating by the chtC mutants is more than a passive recognition of a PST-A cell deficiency by the wild-type members of the chimerae.

The mechanism of cheating seen in chtC is significantly different from that of chtA (fbxA) [8]. Though chtA is an obligatory cheater that is unable to form spores in clonal populations, it differentiates a higher proportion of prespore cells in slugs [8]. The presence of wild-type cells rescues its development, allowing it to differentiate a higher number of spores in chimeric fruiting bodies. On the other hand, even though the chtC mutant has defects in cell-fate maintenance, it is morphologically normal and does not require the presence of wild-type cells to complete development, yet it ends up forming more than its fair share of spores in chimerae with wild-type cells.

Furthermore, while both chtA and chtC increase the prestalk differentiation of their victims, chtA causes the victim's prespore cells to transdifferentiate into stalk cells [8], whereas chtC causes a higher number of the victim's cells to initially differentiate as prestalk cells. These observations suggest that chtC might be affecting wild-type differentiation earlier than the chtA mutant.

The chtC mutants partially overcome the tagB– prestalk defect

The tagB– mutant is morphologically rescued when mixed with AX4 cells, and goes on to complete development, although tagB– cells do not contribute to the PST-A region in the chimerae [14]. However, when mixed with the chtC mutants, tagB– cells become anteriorized and occupy most of the PST-A region, except for the very tip. This finding suggests that the presence of the chtC mutants partially overcomes the tagB– defect. It is therefore likely that the chtC mutants affect their chimeric partners before the tagB gene acts, in the sequence of developmental events. Since the very tip of the slug does not contain tagB– prestalk cells (unlike AX4), it is also likely that tagB– cells are defective in forming several prestalk cell types, and the defect in contributing cells to the very tip of the slug is separate from the PST-A cell defect. The tagA– mutant, on the other hand, is unaffected by the chtC mutants in chimerae, suggesting that the chtC gene functions later than tagA, and consequently the chtC mutants are unable to affect the tagA– cells. These suggestions are consistent with the timing of expression of the three genes - both tagA and chtC are expressed throughout development, but their expression peaks at 2 and 12 hours respectively [21]. The tagB gene is first induced much later, at about 8 hours, and peaks at 20 hours of development [14].

A quality-control “check-point” for PST-A cells?

Both the tagA– and tagB– mutants have defects in prestalk differentiation, similar to the chtC mutants, and both have morphological defects in stalk formation. It has been suggested that the wild type preferentially forms PST-A cells in chimera with these mutants since the mutants are defective in forming those cells [20]. A similar explanation can account for the finding that wild-type cells preferentially contribute to the PST-A region in chimerae with the chtC mutants. Though the chtC mutants do not appear to be functionally defective in stalk formation, they are defective in the expression of prestalk markers. This observation supports the hypothesis that cells with appropriate expression of prestalk genes contribute preferentially to the stalk (especially the PST-A region), possibly as a form of stalk “quality-control”.

The chtC mutants appear to be taking advantage of this PST-A “check-point”. Their presence in chimeric mixtures induces the wild-type cells to form stalk cells even though the chtC mutants have the ability to do so themselves, and this leads to an increase in their own spore production at the expense of their victim. This is thus an example of developmental cheating where in the presence of a genetically distinct strain, a cheater mutant is subverting a developmental pathway to increase its own fitness.

Microbial social behaviors are broadly divided into two categories [25] – the production of public goods, and the formation of fruiting bodies as seen in Dictyostelium and Myxococcus xanthus. While the former is normally concerned with a single (biosynthetic) pathway, the latter may involve various signaling pathways that normally lead to complex developmental processes. Consequently, developmental processes are likely to be manipulated for cheating in these social systems, similar to that seen in super-organisms like social insect colonies. We see an example in this study, where a cheater mutant is manipulating an existing developmental pathway of cell-fate determination and proportioning to exploit other clones. The cooperative system in Dictyostelium thus offers a good opportunity to study developmental cheating mechanisms at the genetic and cellular level.

Materials and Methods

Strains

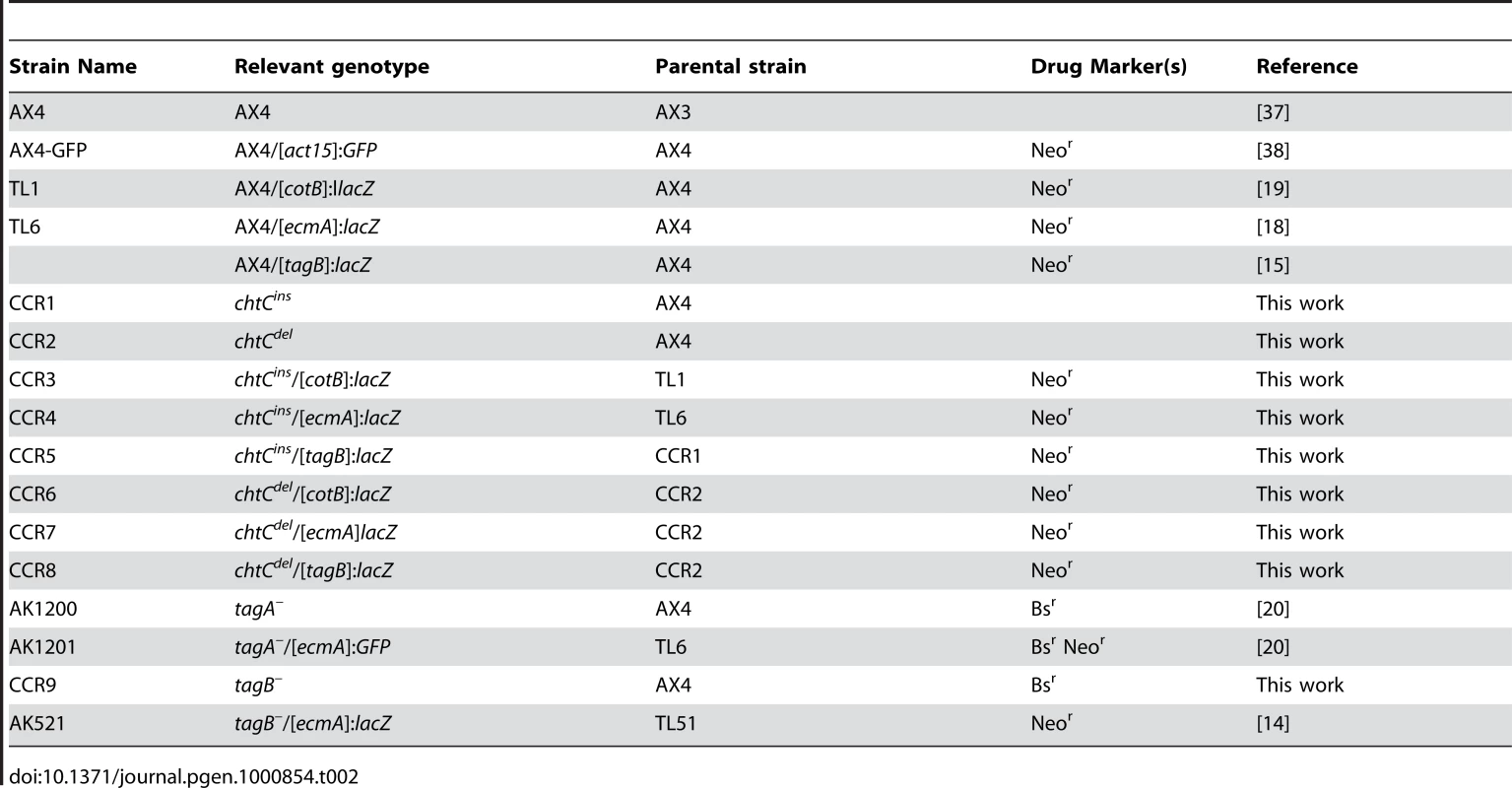

The D. discoideum strains used in this study are described in Table 2. The chtCins strain was described before as the chtC mutant [10]. To generate the chtCdel strain, we amplified two fragments from the knockout vector by PCR (Upstream arm primers: 5′-CTTGACATGCGAAATGGC-3′, 5′-GAAGGGACTCCATAAGTATGAG-3′; downstream arm primers: 5′-GTCTTCCAGATGAAAGTTGC-3′, 5′-CCTAATGCAGCACATACTGC-3′). The PCR fragments were cloned between the KpnI and ClaI sites of the pLPBLP plasmid, and the entire plasmid was used as a knockout construct to delete most of the endogenous chtC gene. For both the chtC mutants, the BSR cassette was subsequently removed by transforming the cells with the pDEX-NLS-Cre plasmid [26]. We also created a Cre-expressing plasmid carrying the hygromycin-resistance cassette to use in strains that are already G418-resistant. We transposed the tetr-hygr cassette from the EZTN::tetr-A15hygr plasmid (a kind gift from J. Williams) into the pDEX-NLS-Cre plasmid (just downstream of the act8 terminator) to generate the pDEX-Cre-hygr plasmid. The tagB– mutant was generated by transforming the ptgB-BSR plasmid (a kind gift from W.F. Loomis) into AX4. ptgB-BSR is a ClaI-rescued plasmid from a REMI insertion of the pBSRdelBglII plasmid into position 2672 of the tagB coding region. The chtCins mutation was generated in the AX4/[cotB]:lacZ (TL1) and AX4/[ecmA]:lacZ (TL6) strains, and the BSR cassette was subsequently removed by transforming cells with the pDEX-Cre-hygr plasmid, to give the chtCins/[cotB]:lacZ and chtCins/[ecmA]:lacZ strains respectively. To create the chtCdel/[cotB]:lacZ, chtCdel/[ecmA]:lacZ, chtCins/[tagB]:lacZ and chtCdel/[tagB]:lacZ strains, we transformed the pSP70-LacZ [19], p63NeoGal [27] or the ptagB/lacZ [15] plasmids into the respective chtC mutants.

Tab. 2. <i>D. discoideum</i> strains used in this study.

Growth, transformation

D. discoideum cells were grown in suspension cultures in HL5 [28] with the necessary supplements. All strains were grown in HL5 medium without antibiotics for 24–48 hours prior to setting up any experiments, to avoid the potential effects of antibiotics on cell behavior. One labeled strain from each background was mixed with AX4-GFP cells to test the effect of the antibiotic on mixing experiments (Figure S5). Plasmid transformation was carried out essentially as described earlier [29], with the following modifications: cells were resuspended at a final density of 3×107 cells/ml before transformation, electroporated twice, and the transformants were recovered in HL5 with 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 hours prior to the addition of drugs. Depending on the plasmids, transformants were selected with either Blasticidin S (10 µg/ml) or G418 (5 µg/ml). Transformants were grown clonally on SM-agar plates in association with K. aerogenes [28], and then re-tested for drug resistance in 24 well-plates containing HL5 with the drug. When appropriate, drug-resistant clones were tested for the correct recombination event by PCR and by Southern blot analysis.

Development and mixing experiments

We developed cells as described earlier [29] with the following modifications: cells were washed with KK2 buffer (16.3 mM KH2PO4, 3.7 mM K2HPO4, pH 6.2), resuspended at a density of 1×108 cells/ml, and 5×107 cells were deposited on each nitrocellulose filter. For the mixes, the cells were grown separately, and mixed before development. We collected all the cells (after 40–48 hours), treated them with 0.1% NP40 to select for spores, and, in the case of GFP-labeled strains, we counted them as described [29]. For mixes with tagB–, the spores were plated out clonally on SM-agar plates in association with K. aerogenes [28], and the plaques were scored by their developmental morphology. For the mixes between the rest of the mutants, spores were plated out similarly, and cells from individual plaques were transferred to two 96-well plates in HL5 containing 10 µg/ml Blasticidin S, and scored for drug-resistance. For the sporulation efficiency experiments, cells were developed as above, and all cells were collected after 40–48 hours of development. NP40-resistance was calculated as the ratio of the number of visible spores after NP40-treatment to the same number prior to NP40-treatment. Sporulation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the NP40-resistant spores obtained to the number of cells originally plated. These spores were then plated out clonally on SM-agar plates in association with K. aerogenes [28] and germination efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the number of plaques obtained to the number of spores plated. For fluorescence microscopy of developing structures with tagA–/[ecmA]:GFP cells, the cells were developed on KK2 plates as described [9]. For the segregation assay, we labeled cells with either CellTracker CMFDA or CellTracker Orange CMRA (Molecular Probes) as described [29]. After labeling, we mixed cells from the appropriate strains at a 1∶1 ratio and a final density of 5×106 cells/ml. We then spotted 40 µl of this cell suspension on KK2 (non-nutrient) agar plates, allowed the cells to develop for 8 hours, and then photographed with both transmitted light and fluorescence microscopy. The fluorescence images were overlaid and are shown as color photographs.

Cell-type specific markers

Developing structures were fixed and stained in situ with X-gal (for β-galactosidase activity) as described previously [18], and were counterstained with 0.02% eosin Y [30]. For each experiment, tens of structures were observed in at least 2 independent biological replications, and representative structures are shown in the figures. Staining of dissociated cells was done essentially as described earlier [18], except that the developing structures were passed through an 18G1½ needle, and treated with pronase (0.1% pronase, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.0) for 10 minutes at room temperature for efficient dissociation. GFP-labeled cells were counted directly after dissociation using phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy. For slug migration, cells were washed twice with double-distilled water, and 108 cells were streaked on 2% Agar-Noble plates made with double-distilled water. The plates were incubated in a dark chamber with a unidirectional source of light for 48 hours, and exposed to overhead light to induce culmination. Developing structures were collected after migration and stained as above. Spore staining was carried out as described previously [18].

Nucleic acid analysis

Genomic DNA was prepared as described earlier by the CTAB method [31]. Southern blot analysis was performed by standard methods [32]. RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis were performed as described previously [33]. The blots were hybridized with DNA probes made by random-primer labeling [34]. We used a PCR fragment from pLAS5 [9] to probe for the chtC gene. The abundance of the chtC mRNA was determined by Q-RT-PCR as described, using rnlA (Ig7) to normalize for cDNA levels [35]. The primers used were: chtC 5′-TTCACCAAATCCACTAGACTGTC-3′ and 5′-CAGTTGCTTTCTTACGTGCAAG-3′and Ig7 5′-TTACATTTATTAGACCCG AAACCAAGC-3′ and 5′-TTCCCTTTAGACCTATGGACCTTAGCG-3′. The abundance of the tagB mRNA was also similarly determined by Q-RT-PCR (primers: 5′-TTTCCCAACTGGCGAATC-3′ and 5′-CCTAAACCACCGATACCAATC-3′). In situ RNA hybridization was done as described [36] with the following modifications: hybridization was done in the same solution as the pre-hybridization; both steps, as well as washing were done at 50°C, and the final wash was done in 0.1X SSC. A digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe was made by in vitro transcription from the plasmid pLAS5 using the T7 promoter with the DIG RNA labeling kit from Roche.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Maynard SmithJ

SzathmáryE

1997 The major transitions in evolution: Oxford University Press, USA.

2. AbbotP

WithgottJH

MoranNA

2001 Genetic conflict and conditional altruism in social aphid colonies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 12068

3. HughesWOH

BoomsmaJJ

2008 Genetic royal cheats in leaf-cutting ant societies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 5150

4. WenseleersT

RatnieksFLW

de F RibeiroM

de A AlvesD

Imperatriz-FonsecaVL

2005 Working-class royalty: bees beat the caste system. Biology Letters 1 125

5. KessinRH

2001 Dictyostelium: evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity: Cambridge University Press.

6. GilbertOM

FosterKR

MehdiabadiNJ

StrassmannJE

QuellerDC

2007 High relatedness maintains multicellular cooperation in a social amoeba by controlling cheater mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 8913

7. StrassmannJE

ZhuY

QuellerDC

2000 Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 408 965 967

8. EnnisHL

DaoDN

PukatzkiSU

KessinRH

2000 Dictyostelium amoebae lacking an F-box protein form spores rather than stalk in chimeras with wild type. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97 3292

9. SantorelliLA

ThompsonCRL

VillegasE

SvetzJ

DinhC

2008 Facultative cheater mutants reveal the genetic complexity of cooperation in social amoebae. Nature 451 1107

10. KhareA

SantorelliLA

StrassmannJE

QuellerDC

KuspaA

2009 Cheater-resistance is not futile. Nature 461 980 982

11. SilloA

BloomfieldG

BalestA

BalboA

PergolizziB

2008 Genome-wide transcriptional changes induced by phagocytosis or growth on bacteria in Dictyostelium. BMC Genomics 9 291

12. EichingerL

2006 Dictyostelium discoideum protocols: Humana Press.

13. HuangE

BlaggSL

KellerT

KatohM

ShaulskyG

2006 bZIP transcription factor interactions regulate DIF responses in Dictyostelium. Development 133 449 458

14. ShaulskyG

KuspaA

LoomisWF

1995 A multidrug resistance transporter/serine protease gene is required for prestalk specialization in Dictyostelium. Genes & Development 9 1111 1122

15. ShaulskyG

LoomisWF

1996 Initial Cell Type Divergence in Dictyostelium is Independent of DIF-1. Developmental Biology 174 214 220

16. JermynKA

DuffyKTI

WilliamsJG

1989 A new anatomy of the prestalk zone in Dictyostelium. Nature 340 144 146

17. RaperKB

1940 Pseudoplasmodium formation and organization in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Elisha Mitchell Sci Soc 56 241 282

18. ShaulskyG

LoomisWF

1993 Cell type regulation in response to expression of ricin A in Dictyostelium. Developmental Biology 160 85 98

19. FosnaughKL

LoomisWF

1993 Enhancer regions responsible for temporal and cell-type-specific expression of a spore coat gene in Dictyostelium. Developmental biology 157 38

20. CabralM

AnjardC

LoomisWF

KuspaA

2006 Genetic Evidence that the Acyl Coenzyme A Binding Protein AcbA and the Serine Protease/ABC Transporter TagA Function Together in Dictyostelium discoideum Cell Differentiation? Eukaryotic Cell 5 2024 2032

21. GoodJR

CabralM

SharmaS

YangJ

Van DriesscheN

2003 TagA, a putative serine protease/ABC transporter of Dictyostelium that is required for cell fate determination at the onset of development. Development 130 2953 2965

22. ChangWT

NewellPC

GrossJD

1996 Identification of the cell fate gene stalky in Dictyostelium. Cell 87 471 482

23. JaiswalJK

MujumdarN

MacWilliamsHK

NanjundiahV

2006 Trishanku, a novel regulator of cell-type stability and morphogenesis in Dictyostelium discoideum. Differentiation 74 596 607

24. MohantyS

FirtelRA

1999 Control of spatial patterning and cell-type proportioning in Dictyostelium. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 597 608

25. WestSA

DiggleSP

BucklingA

GardnerA

GriffinAS

2007 The social lives of microbes. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 38 53 77

26. FaixJ

KreppelL

ShaulskyG

SchleicherM

KimmelAR

2004 A rapid and efficient method to generate multiple gene disruptions in Dictyostelium discoideum using a single selectable marker and the Cre-loxP system. Nucleic Acids Research 32 e143

27. JermynKA

WilliamsJG

1991 An analysis of culmination in Dictyostelium using prestalk and stalk-specific cell autonomous markers. Development 111 779 787

28. SussmanM

1987 Cultivation and synchronous morphogenesis of Dictyostelium under controlled experimental conditions. Methods Cell Biol 28 9 29

29. OstrowskiEA

KatohM

ShaulskyG

QuellerDC

StrassmannJE

2008 Kin Discrimination Increases with Genetic Distance in a Social Amoeba. PLoS Biol 6 e287 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060287

30. InsallR

1994 CRAC, a cytosolic protein containing a pleckstrin homology domain, is required for receptor and G protein-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. The Journal of Cell Biology 126 1537 1545

31. KatohM

CurkT

XuQ

ZupanB

KuspaA

2006 Developmentally Regulated DNA Methylation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryotic Cell 5 18 25

32. VollrathD

DavisRW

ConnellyC

HieterP

1988 Physical Mapping of Large DNA by Chromosome Fragmentation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 85 6027 6031

33. KiblerK

NguyenTL

SvetzJ

DriesscheNV

IbarraM

2003 A novel developmental mechanism in Dictyostelium revealed in a screen for communication mutants. Developmental Biology 259 193 208

34. FeinbergAP

VogelsteinB

1983 A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Analytical Biochemistry 132 6 13

35. BenabentosR

HiroseS

SucgangR

CurkT

KatohM

2009 Polymorphic Members of the lag Gene Family Mediate Kin Discrimination in Dictyostelium. Current Biology 19 567 572

36. EscalanteR

LoomisWF

1995 Whole-Mount in Situ Hybridization of Cell-Type-Specific mRNAs in Dictyostelium. Developmental Biology 171 262 266

37. KnechtDA

CohenSM

LoomisWF

LodishHF

1986 Developmental regulation of Dictyostelium discoideum actin gene fusions carried on low-copy and high-copy transformation vectors. Molecular and Cellular Biology 6 3973 3983

38. FosterKR

ShaulskyG

StrassmannJE

QuellerDC

ThompsonCRL

2004 Pleiotropy as a mechanism to stabilize cooperation. Nature 431 693 696

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the GenomeČlánek Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in MiceČlánek Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' DiseaseČlánek Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD TagsČlánek Wing Patterns in the Mist

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 2

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Scale of Population Structure in

- Allelic Exchange of Pheromones and Their Receptors Reprograms Sexual Identity in

- Genetic and Functional Dissection of and in Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- A Single Nucleotide Polymorphism within the Acetyl-Coenzyme A Carboxylase Beta Gene Is Associated with Proteinuria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling

- Genome-Wide Association Study in Asian Populations Identifies Variants in and Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Cdk2 Is Required for p53-Independent G/M Checkpoint Control

- Uncoupling of Satellite DNA and Centromeric Function in the Genus

- Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in the Clade

- Use of DNA–Damaging Agents and RNA Pooling to Assess Expression Profiles Associated with and Mutation Status in Familial Breast Cancer Patients

- Cheating by Exploitation of Developmental Prestalk Patterning in

- Replication and Active Demethylation Represent Partially Overlapping Mechanisms for Erasure of H3K4me3 in Budding Yeast

- Cdk1 Targets Srs2 to Complete Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing and to Promote Recombinational Repair

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Susceptibility Variants for Type 2 Diabetes in Han Chinese

- Genome-Wide Identification of Susceptibility Alleles for Viral Infections through a Population Genetics Approach

- Transcriptional Rewiring of the Sex Determining Gene Duplicate by Transposable Elements

- Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in

- Proteasome Nuclear Activity Affects Chromosome Stability by Controlling the Turnover of Mms22, a Protein Important for DNA Repair

- Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in Mice

- Structure, Function, and Evolution of the spp. Genome

- Human and Non-Human Primate Genomes Share Hotspots of Positive Selection

- A Kinase-Independent Role for the Rad3-Rad26 Complex in Recruitment of Tel1 to Telomeres in Fission Yeast

- Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' Disease

- Molecular Evolution and Functional Characterization of Insulin-Like Peptides

- Molecular Poltergeists: Mitochondrial DNA Copies () in Sequenced Nuclear Genomes

- Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD Tags

- Wing Patterns in the Mist

- DNA Binding of Centromere Protein C (CENPC) Is Stabilized by Single-Stranded RNA

- Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Multiple Loci Associated with Primary Tooth Development during Infancy

- Mutations in , Encoding an Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter ENT3, Cause a Familial Histiocytosis Syndrome (Faisalabad Histiocytosis) and Familial Rosai-Dorfman Disease

- Genome-Wide Identification of Binding Sites Defines Distinct Functions for PHA-4/FOXA in Development and Environmental Response

- Ku Regulates the Non-Homologous End Joining Pathway Choice of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Human Somatic Cells

- Nucleoporins and Transcription: New Connections, New Questions

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study in Asian Populations Identifies Variants in and Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Nucleoporins and Transcription: New Connections, New Questions

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání