-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaProgrammed Protection of Foreign DNA from Restriction Allows Pathogenicity Island Exchange during Pneumococcal Transformation

In bacteria, transformation and restriction-modification (R-M) systems play potentially antagonistic roles. While the former, proposed as a form of sexuality, relies on internalized foreign DNA to create genetic diversity, the latter degrade foreign DNA to protect from bacteriophage attack. The human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae is transformable and possesses either of two R-M systems, DpnI and DpnII, which respectively restrict methylated or unmethylated double-stranded (ds) DNA. S. pneumoniae DpnII strains possess DpnM, which methylates dsDNA to protect it from DpnII restriction, and a second methylase, DpnA, which is induced during competence for genetic transformation and is unusual in that it methylates single-stranded (ss) DNA. DpnA was tentatively ascribed the role of protecting internalized plasmids from DpnII restriction, but this seems unlikely in light of recent results establishing that pneumococcal transformation was not evolved to favor plasmid exchange. Here we validate an alternative hypothesis, showing that DpnA plays a crucial role in the protection of internalized foreign DNA, enabling exchange of pathogenicity islands and more generally of variable regions between pneumococcal isolates. We show that transformation of a 21.7 kb heterologous region is reduced by more than 4 logs in dpnA mutant cells and provide evidence that the specific induction of dpnA during competence is critical for full protection. We suggest that the integration of a restrictase/ssDNA-methylase couplet into the competence regulon maintains protection from bacteriophage attack whilst simultaneously enabling exchange of pathogenicicy islands. This protective role of DpnA is likely to be of particular importance for pneumococcal virulence by allowing free variation of capsule serotype in DpnII strains via integration of DpnI capsule loci, contributing to the documented escape of pneumococci from capsule-based vaccines. Generally, this finding is the first evidence for a mechanism that actively promotes genetic diversity of S. pneumoniae through programmed protection and incorporation of foreign DNA.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003178

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003178Summary

In bacteria, transformation and restriction-modification (R-M) systems play potentially antagonistic roles. While the former, proposed as a form of sexuality, relies on internalized foreign DNA to create genetic diversity, the latter degrade foreign DNA to protect from bacteriophage attack. The human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae is transformable and possesses either of two R-M systems, DpnI and DpnII, which respectively restrict methylated or unmethylated double-stranded (ds) DNA. S. pneumoniae DpnII strains possess DpnM, which methylates dsDNA to protect it from DpnII restriction, and a second methylase, DpnA, which is induced during competence for genetic transformation and is unusual in that it methylates single-stranded (ss) DNA. DpnA was tentatively ascribed the role of protecting internalized plasmids from DpnII restriction, but this seems unlikely in light of recent results establishing that pneumococcal transformation was not evolved to favor plasmid exchange. Here we validate an alternative hypothesis, showing that DpnA plays a crucial role in the protection of internalized foreign DNA, enabling exchange of pathogenicity islands and more generally of variable regions between pneumococcal isolates. We show that transformation of a 21.7 kb heterologous region is reduced by more than 4 logs in dpnA mutant cells and provide evidence that the specific induction of dpnA during competence is critical for full protection. We suggest that the integration of a restrictase/ssDNA-methylase couplet into the competence regulon maintains protection from bacteriophage attack whilst simultaneously enabling exchange of pathogenicicy islands. This protective role of DpnA is likely to be of particular importance for pneumococcal virulence by allowing free variation of capsule serotype in DpnII strains via integration of DpnI capsule loci, contributing to the documented escape of pneumococci from capsule-based vaccines. Generally, this finding is the first evidence for a mechanism that actively promotes genetic diversity of S. pneumoniae through programmed protection and incorporation of foreign DNA.

Introduction

While sexual reproduction, which is crucial for genetic diversity in eukaryotes, is lacking in bacteria, genetic transformation is regarded as a substitute [1]. Genetic transformation proceeds through the internalization of single stranded (ss) DNA fragments created from an exogenous double stranded (ds) DNA substrate, which are incorporated into the genome by homology. This forms a heteroduplex of one strand of host DNA associated with complementary exogenous ssDNA, which is resolved by replication, producing one wild-type daughter chromosome, and one possessing the mutation originally present on the exogenous DNA. This widespread process [2] contributes to genetic plasticity of the major human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) [3], potentially leading to antibiotic resistance acquisition and vaccine escape [4]. Current pneumococcal vaccines target the polysaccharide capsule, which is considered the main pneumococcal virulence factor, and of which over 90 different serotypes exist [5]. Cumulatively, these serotype loci are almost equivalent in size to a single pneumococcal genome, demonstrating the high levels of genetic diversity present in the pneumococcal population. Vaccine escape presumably occurs via exchange of capsule loci, ranging in size from 10.3 kb to 30.3 kb, by transformation. These loci occupy the same position in the genome, between the dexB and aliA genes which provide flanking homology for chromosomal integration of heterologous capsule sequences.

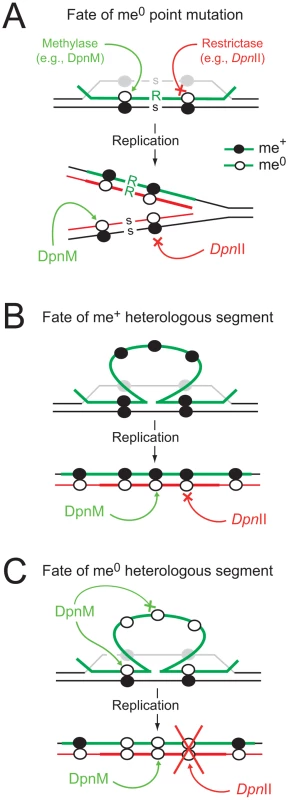

On the other hand, many bacteria possess DNA restriction-modification (R-M) systems, which defend against invasion by foreign DNA such as bacteriophage, and are seen as restrictive to genetic diversity, potentially antagonizing genetic exchange processes. R-M systems classically encode a restrictase, which degrades unmethylated (me0) foreign dsDNA, and a methylase which methylates the dsDNA of the host genome, protecting it from the restrictase [6]. In the course of transformation and despite the widely accepted notion that R-M systems antagonize genetic exchange processes, internalized me0 ssDNA is resistant to restriction as most restrictases cannot cut ssDNA. Upon transfer of a point mutation, heteroduplex formation produces hemimethylated (me+/0) dsDNA, which remains resistant to restriction, but can be methylated by the dsDNA methylase (Fig. 1A). Resolution of the heteroduplex by replication then forms two me+/0 dsDNA, which again remain resistant to restriction. As a result, at no point during the transfer of a point mutation is the internalized or chromosomally-integrated DNA sensitive to restriction. The situation is potentially different for the transfer of heterologous DNA, since the heterologous region remains in the form of a ss loop after heteroduplex formation, flanked by regions of homology (Fig. 1BC). In the case of methylated (me+) transforming DNA, this should not be problematic, as the integrated ssDNA is already methylated, confering resistance to restriction to the dsDNA formed at the region of heterology after resolution of the heteroduplex by replication (Fig. 1B). However, in the case of me0 transforming DNA, resolution of the heteroduplex by replication creates me0 dsDNA, which should be sensitive to restriction (Fig. 1C). As a result, classical R-M systems should severely limit the acquisition of heterologous sequences of me0 origin.

Fig. 1. Diagrammatic representation of the impact of R-M systems on transformation.

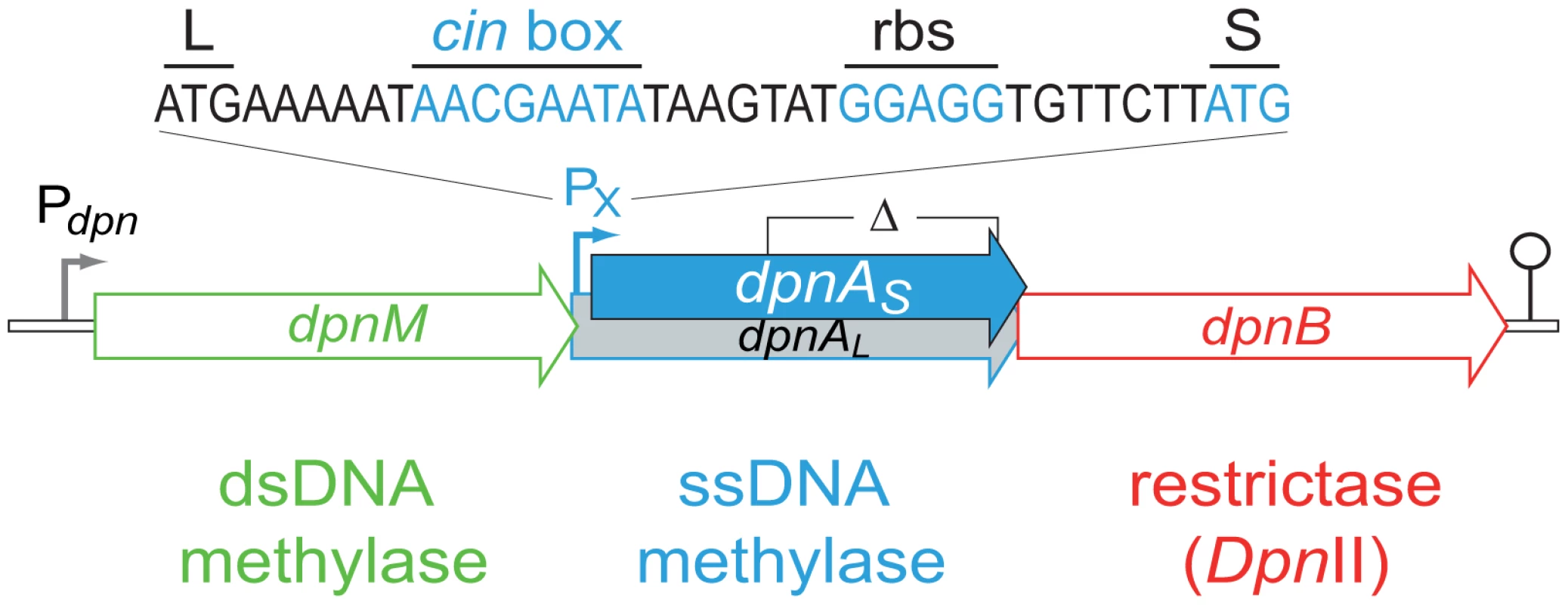

(A) Integration of a point mutation carried by me0 donor DNA is not affected by restriction. Color code: green, transforming (donor) DNA; black, host DNA; grey, displaced recipient strand; red, newly replicated DNA. me+ DNA shown as closed circles and me0 DNA as open circles; point mutation as R in donor and s for recipient. (B) Integrated me+ heterologous donor DNA is resistant to DpnII, which is unable to cleave me+/0 dsDNA produced by replication. Color code as above; thick red, neosynthesized complement to heterology. (C) Integrated me0 heterologous donor DNA is sensitive to restrictase (e.g., DpnII) because me0 dsDNA is produced by replication. We hypothesize that DpnA, which, unlike DpnM, acts on ssDNA, protects the transformation intermediate by ensuring production of me+/0 dsDNA after replication (as in panel B). S. pneumoniae strains possess one of two complementary R-M systems, DpnI or DpnII [7], encoded at a common location in the chromosome [8]. DpnI is an atypical restriction enzyme, as it cleaves me+ dsDNA. Chromosomal DNA produced by replication in DpnI cells is me0 and therefore is not sensitive to DpnI restriction. In contrast to this, DpnII strains possess a classical companion dsDNA methylase (DpnM), which methylates host DNA after replication, rendering the chromosome resistant to the DpnII restrictase (encoded by dpnB), while DpnII protects the cell from me0 bacteriophage attack by restricting me0 dsDNA. The dpnII locus also encodes DpnA (Fig. 2), a methylase with the unusual ability to specifically modify ssDNA (ss-methylase). Whilst the locus is under the control of the constitutive Pdpn promoter, dpnA is also specifically induced from PX, a competence-inducible (cin) promoter recognized by the competence-specific σ factor, ComX [9],[10]. This alternative σ is transiently active when pneumococcal cells become competent for genetic transformation [11] and required for synthesis and assembly of a dedicated complex for uptake and integration of exogenous DNA into the chromosome, known as the transformasome [12].

Fig. 2. Organization of the dpnII locus.

Schematic representation of the locus in S. pneumoniae, with the identity of the competence-induced promoter and DpnA start codons indicated. Open circle, terminator. Pdpn and PX, σ70 and σX dependent promoters, respectively; L and S, start codon of dpnAL and dpnAS, respectively; cin box, σX binding site; rbs, ribosome-binding site. The limits of the deletion internal to dpnA (Δ) previously constructed [13] and used in this study are indicated. The primary role of DpnA was suggested to be protection of plasmids taken up by genetic transformation from DpnII restriction, via methylation of internalized plasmid ssDNA fragments [13],[11]. Authors demonstrated that installation of me0 plasmids in S. pneumoniae was drastically reduced in a DpnII strain lacking DpnA, and concluded that DpnA biological role was to protect me0 plasmids from DpnII [13]. However, this appeared unlikely to be the function of DpnA, since plasmids naturally carried by S. pneumoniae are extremely rare [14],[15] and plasmid transformation is strikingly inefficient in this species [16]. An alternative hypothesis was therefore proposed, that the role of DpnA was to protect heterologous me0 ssDNA to allow exchange of pathogenicity islands and, more generally, plasticity islands, defined as chromosomal regions variable between pneumococcal isolates [3]. According to this hypothesis, DpnA should methylate internalized transforming me0 ssDNA. Resolution of the transformation heteroduplex by replication should then result in formation of me+/0 rather than me0 dsDNA, thus protecting the transformed chromosome from restriction by DpnII. Thus, methylation of me0 transforming ssDNA by DpnA should be crucial for exchange of plasticity islands. Conversely, the absence of DpnA should leave the resulting transformants sensitive to DpnII (Fig. 1C), which should restrict the chromosome, killing the cell.

Recently, evidence was obtained that the inefficiency of plasmid transformation is presumably intrinsic to the transformasome, due to the competence-induced ssDNA-binding protein, SsbB. We showed that SsbB protects internalized ssDNA and creates a reservoir favoring chromosomal transformation [17]. In contrast, SsbB was found to antagonize plasmid transformation [17], strongly suggesting that the pneumococcal transformasome has evolved to optimize chromosomal but not plasmid transformation. This conclusion prompted us to explore and validate the above-described hypothesis that DpnA is crucial for exchange of plasticity islands [3].

In this study, we show that in the absence of DpnA, acquisition of large me0 heterologous regions is drastically reduced. We also demonstrate that σX-dependent induction of dpnA during competence is required for full protection of me0 foreign DNA. We conclude that the competence-induction of dpnA and the methylation of me0 ssDNA by DpnA are crucial for protection of foreign me0 DNA, allowing exchange of pathogenicicy islands such as the capsule locus. We conclude that the recruitment of dpnA and dpnB (encoding DpnII) into the competence regulon provides the pneumococcus with protection from me0 bacteriophage through the action of DpnII, whilst maintaining the potential of acquisition of me0 pathogenicity islands (e.g., of DpnI origin) via the protective role of ssDNA methylation by DpnA.

Results

DpnA is critical for the efficient acquisition of me0 pathogenicity islands by DpnII strains

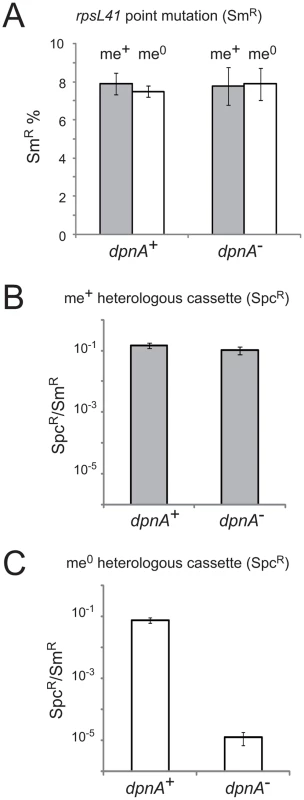

In order to validate our hypothesis that DpnA should be important for transfer of me0 heterologous pathogenicicy islands in DpnII strains, we created a series of isogenic strains possessing the full dpnII locus, or the dpnII locus with a previously characterized internal deletion of dpnA [13] (Fig. 2). We compared the transformation efficiency of cassettes on donor chromosomal DNA from either DpnI (me0) or DpnII (me+) origin in dpnA+ and dpnA− competent cells. We began by confirming a previous conclusion, based on indirect comparisons between non-isogenic pairs of donor and recipient cells, that DpnA plays no role in transformation of a chromosomal point mutation [13] using rpsL41 (conferring streptomycin resistance, SmR) [18] (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Methylation of ssDNA by DpnA is crucial for protection of heterologous me0 DNA from DpnII restriction.

(A) Transformation efficiency of point mutation rpsL41 in recipients with and without DpnA. Dark grey and white columns represent respectively me+ and me0 donor DNA. Error bars are calculated from triplicate repeats of experiments (N = 3). Strains used: donor, TD153 (DpnI, rpsL41) and R3026 (DpnII, rpsL41); recipient, R3087 (DpnII) and R3088 (DpnII, dpnA−). (B) Transformation efficiency of me+ heterologous cps2E::spc7C cassette in dpnA+ and dpnA− recipients. Values shown are normalized to an rpsL41 point mutation also present on the donor DNA. Error bars are calculated from triplicate repeats of experiments (N = 3). Strains used: donor, R3026 (DpnII, cps2E::spc7C, rpsL41); recipient, R3087 (DpnII) and R3088 (DpnII, dpnA−). (C) Transformation efficiency of me0 heterologous cassette in dpnA+ and dpnA− recipients. See panel B legend. Strain used as donor, TD153 (DpnI, cps2E::spc7C, rpsL41); same recipients as in panel B. See Fig. 1 for interpretations. We then tested the efficiency of transformation of a cps2E::spc cassette from either DpnI (me0) or DpnII (me+) donor DNA into DpnII recipients with or without dpnA. This transformation required integration of ∼8.7 kb of heterology within the capsule locus. Efficiency was compared to that obtained with the rpsL41 SmR point mutation on the same donor DNA. As expected, there was no deficit in transformation efficiency in a dpnA− recipient when the donor DNA was me+ (Fig. 3B). In contrast, a >4-log deficit in transformation efficiency was observed when the donor DNA was me0 (Fig. 3C). This is because in presence of DpnA, prior methylation of ssDNA protects resulting transformants (as in Fig. 1B), and in absence of DpnA, the incorporated DNA remains me0, and resulting transformants are sensitive to DpnII restriction (as in Fig. 1C). This result confirms that protection of heterologous me0 donor DNA from restriction by DpnA-mediated methylation is crucial for successful transfer.

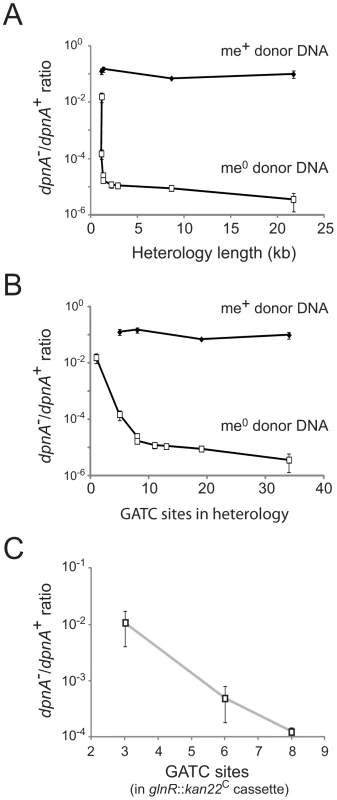

The number of GATC sites present in me0 heterologous DNA determines importance of DpnA-mediated protection

The cps2E::spc cassette represents a large heterology, with 19 GATC sites available for DpnII restriction. To determine whether DpnA was required to protect shorter regions of heterology, with fewer GATC sites, transfer of five further cassettes (Table 1) was compared. The results, presented as ratio of transformation frequency in dpnA− cells compared to dpnA+ cells (after normalization to that of the SmR point mutation present on the same donor DNA), termed dpnA−/+ ratio, show that longer heterologies are correspondingly more dependent on DpnA for protection (Fig. 4A). Indeed, most of the transfers result in a deficit in dpnA−/+ ratio of 3 to 4 logs between me+ and me0 donor DNA, reinforcing the importance of DpnA for protection of these me0 heterologous cassettes.

Fig. 4. Importance of DpnA-mediated protection from restriction is dependent on the number of GATC sites present in the heterologous cassette.

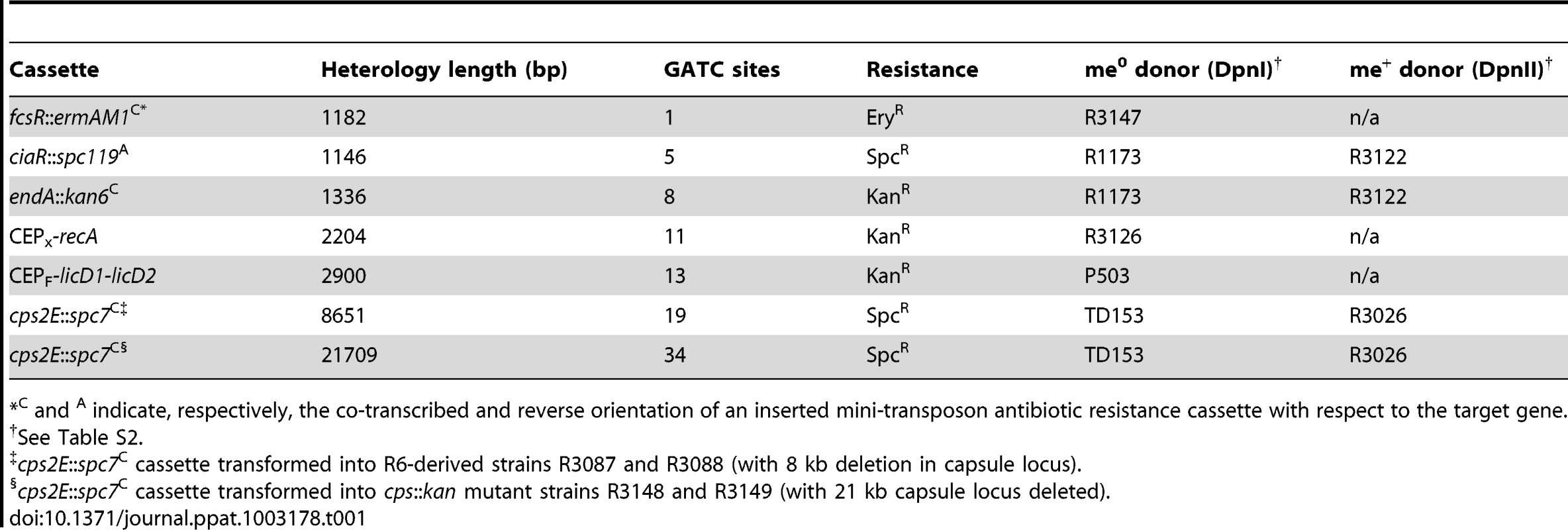

(A) Relationship between heterology length and dpnA− to dpnA+ ratio. Ratios represent transformation efficiency in dpnA− compared to dpnA+. me+ donor DNA, closed diamonds. me0 DNA, open squares. Error bars are calculated from triplicate repeats of experiments (N = 3). Cassettes transferred and donor strains can be found in Table 1. Recipient strains: R3087 (DpnII); R3088 (DpnII, dpnA−); R3163 (DpnII) and R3164 (DpnII, dpnA−) were used for transfer of fcsR::ermAM1C to overcome antibiotic incompatibilities. To create the 21.7 kb heterology, the following recipient strains were used, which lacked the fully capsule locus: R3148 (DpnII, cps::kan) and R3149 (DpnII, dpnA−, cps::kan). (B) Relationship between number of GATC sites in donor heterologous cassette and dpnA− to dpnA+ ratio. Same experiment as in panel A, but with ratios plotted against GATC sites in the heterology. (C) Comparison of transformation efficiency of glnR::kan22C cassettes with varying number of GATC sites. me+ donor DNA was not tested. Error bars as in panel A legend. Strains used: donor, R3154 (DpnI, glnR::kan22C (8), rpsL41), R3238 (DpnI, glnR::kan22C (3), rpsL41) and R3239 (DpnI, glnR::kan22C (6), rpsL41); recipient, R3087 (DpnII) and R3088 (DpnII, dpnA−). Tab. 1. Information on heterology cassettes used in this study.

C and A indicate, respectively, the co-transcribed and reverse orientation of an inserted mini-transposon antibiotic resistance cassette with respect to the target gene. This relationship could simply reflect the increased probability of finding GATC sites with increasing heterologous segment length (Fig. 4B). To establish whether the number of GATC sites is important in determining the dependence on methylation of ssDNA by DpnA, we modified the glnR::kan22C cassette to create derivatives with the same heterology length (1,336 bp) but with 3 (glnR::kan22C (3)), 6 (glnR::kan22C (6)) or 8 (glnR::kan22C (8)) me0 GATC sites. If the number of GATC sites present in the heterologous DNA determined the reliance of successful transfer on DpnA-mediated methylation of ssDNA, we expected that glnR::kan22C (3) should transfer into a dpnA− strain with higher efficiency than glnR::kan22C (6), which should in turn transfer with greater efficiency than the wild-type glnR::kan22C (8) cassette. The results confirm this prediction, showing that the dpnA−/+ ratio of transformation frequencies is inversely proportional to the number of GATC sites in the heterology, with transformation efficiency in dpnA− recipient cells decreasing as GATC sites in donor heterology region increase (Fig. 4C). The number of GATC sites present in the heterologous donor DNA thus determines the importance of DpnA, suggesting that the ss-methylase is particularly important for the transfer of long heterologous regions of me0 DNA. We propose that absence of DpnA results in direct competition between DpnM and DpnII for access to integrated me0 dsDNA following replication, where DpnM must methylate all GATC sites to protect the chromosome before DpnII restricts a single one. As a result, increasing the number of heterologous GATC sites favors DpnII in this competition, resulting in greater loss of transformant cells, since a greater proportion are destroyed by DpnII.

The vast majority of DpnA is produced during competence for genetic transformation

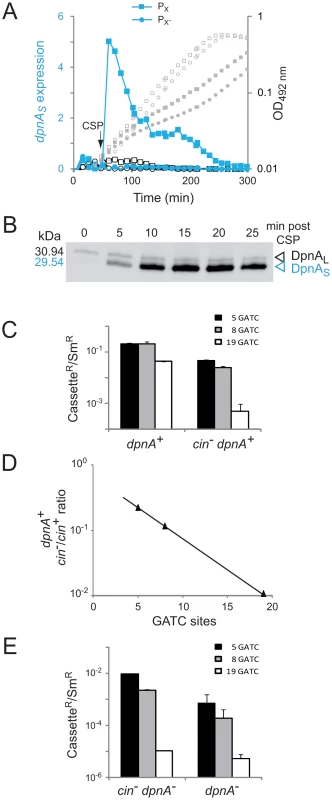

Although it was previously shown that DpnA is specifically induced during competence for genetic transformation [11], the specific induction profile of DpnA was not established. Prior to determining the importance of DpnA competence induction for protection of me0 heterologous transforming DNA, we further explored the expression of DpnA during competence induction. Firstly, ectopic luciferase reporter fusion assays confirmed that the wild type ComX-dependent promoter, PX, was induced by competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) [19], whilst a promoter with a mutated cin box, PX-, was completely inactive (Fig. 5A). Secondly, a time course Western-blot showed that DpnA was expressed in two forms, a longer form, weakly constitutively expressed from Pdpn (DpnAL), and a shorter form specifically expressed from PX during competence (DpnAS) (Fig. 5B). The observation of both DpnAL and DpnAS proteins in competent pneumococcal cells establishes that the two forms previously observed in E. coli extracts [13] are biologically relevant. These results demonstrate that although a small proportion of DpnA is constitutively produced, the vast majority of DpnA is produced during competence for genetic transformation.

Fig. 5. Induction of dpnA during competence is critical to ensure full protection of transforming heterologous DNA from restriction by DpnII.

(A) Expression of dpnAS is dependent on the cin box in PX. Expression (RLU/OD values) is represented by blue (with CSP) and black lines with symbols, whilst OD values are represented by grey symbols. The (PX)-luc reporter is represented by squares, and the mutated (PX-)-luc by circles. Closed shapes represent cultures which received CSP after 50 min incubation (arrow), whilst open shapes correspond to those without CSP. Strains used: R2323 ((PX)-luc) and R3233 ((PX-)-luc). (B) Expression of DpnA during competence. Whole extracts of cells containing a DpnA-SPA fusion were analyzed by Western-blot using anti-Flag antibodies (Text S1). Note that we routinely use these antibodies to detect many other pneumococcal proteins tagged with the SPA tag and do not observe the band we identify as DpnAL. Strain used: R3562 (DpnII, dpnA-SPA). (C) Transformation efficiencies of heterologous cassettes in dpnA+ and cin− dpnA+ strains. ciaR::spc119A (5 GATC) in black, endA::kan6C (8 GATC) in grey, cps2E::spc7C (19 GATC) in white. Error bars are calculated from triplicate repeats of experiments (N = 3). Strains used: donor, TD153 (DpnI, cps2E::spc7C, rpsL41) and R1173 (DpnI, ciaR::spc119A, endA::kan6C, rpsL41); recipient, R3087 (DpnII) and R3190 (DpnII, cin− dpnA+). (D) Ratios of transfer efficiency of heterologous cassettes between cin− dpnA+ and cin+ dpnA+ strains. (E) Transformation efficiencies of heterologous cassettes in cin− dpnA− and cin+ dpnA− strains. Cassettes and error bars as in panel C. Strains used, donor as in panel C; recipient, R3088 (DpnII, dpnA−) and R3642 (DpnII, cin− dpnA−). Competence induction of DpnA is crucial for full protection of me0 heterologous DNA

The importance of DpnA competence induction for pathogenicicy island exchange was investigated by mutating PX in the dpnII locus, and comparing the transfer efficiency of me0 cassettes in this recipient (cin− dpnA+) to that in a dpnA+ recipient. Results showed that induction of DpnA during competence was crucial for full protection and transfer of me0 heterologous DNA, as transformation efficiency of me0 cassettes decreased substantially in the cin− dpnA+ recipient strain (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, comparing the ratio of transfer between cin+ dpnA+ and cin− dpnA+ recipient strains showed that an increase in the number of heterologous GATC sites reinforced the importance of competence induction of DpnA (Fig. 5D). As noted above, this is likely due to the fact that DpnM and DpnII compete directly for access to me0 GATC sites in the chromosome after integration of me0 heterologous DNA and replication.

It is of note that mutating the cin box in an otherwise dpnA− recipient (i.e., rendering the cell cin− dpnA−) increased transformation efficiency compared to cin+ dpnA− cells (Fig. 5E). We attribute this increase to the non-induction of dpnB at competence, which results in lower levels of DpnII, shifting the competition between DpnM and DpnII for access to GATC sites in favor of the former, and thus increasing the probability that me0 dsDNA GATC sites will be protected after replication.

Discussion

A critical protective role of the ss-methylase DpnA for exchange of pathogenicicy islands

The primary role of the DpnII R-M system is to protect the pneumococcus from attack by me0 bacteriophage [13]. Here we show that the ss-methylase DpnA permits acquisition of me0 pathogenicicy islands (e.g., from DpnI pneumococci) via methylation of internalized foreign heterologous me0 ssDNA (Fig. 3C). Transformation of a 21.7 kb heterologous region is thus reduced by more than 4 logs in dpnA mutant cells. DpnA-dependent methylation occurring before as well as possibly after integration (i.e., at the heteroduplex stage; Fig. 1C) renders the incorporated dsDNA resistant to DpnII after replication (Fig. 1B), and ensures the survival of the transformed cell, allowing exchange of pathogenicicy islands between DpnI and DpnII populations.

Competence induction of DpnA is crucial for full protection of me0 heterologous DNA

A time course Western-blot following CSP addition revealed that the vast majority of DpnA is produced during competence for genetic transformation (Fig. 5B). The importance of competence induction of dpnA for acquisition of heterologous DNA was evaluated through inactivation of the cin box, bound by σX, revealing a ∼100-fold reduction in transformation for a segment harboring 19 GATC sites (Fig. 5C and 5D). This reduction establishes that for such a large heterology ∼99% of the protection relied on DpnA molecules synthesized at competence.

It is of note that when comparing heterologous transfers in dpnA+ and cin− dpnA+ recipients to assess the impact of dpnA competence induction, we likely underestimate the true importance of this induction. We observed that the transformation efficiency in a cin− dpnA+ strain remains higher than in a cin+ dpnA− equivalent (compare Fig. 5C and 5E), and attribute this to two factors. Firstly, DpnAL remains (weakly) constitutively expressed in cin− dpnA+ strains. Secondly, we have shown that dpnB (encoding DpnII), as well as dpnA, is part of the competence regulon (Fig. 5E). As a result, mutating PX reduces not only DpnA but also DpnII levels, which should favor DpnM in the race against DpnII, allowing survival of more recombinants and resulting in underestimation of the effect of non-induction of DpnA during competence.

Since the vast majority of DpnA is produced during competence (Fig. 5B), we conclude that the induction of DpnA is critical for full protection of heterologous ssDNA internalized during competence. We have shown DpnA-mediated protection to be especially important in the case of large pathogenicicy islands (Fig. 4A). The number of GATC sites, which are targeted by DpnII, being proportional to length of heterologous regions and the abundance of these sites dictating the probability of restriction by DpnII (Fig. 4) readily explain this observation.

Evolutionary significance of the recruitment of dpnA and dpnB into the com regulon

The position of the PX promoter downstream of dpnM (Fig. 2) results in induction of both dpnA and dpnB, but not dpnM, during competence. What could the biological relevance of this organization be? A first advantage we see in the recruitment of dpnA to protect transforming DNA is that the window of opportunity for DpnA methylation of heterologous ssDNA is long, existing between internalization of exogenous ssDNA, and the passage of the replication fork over the recombinant chromosome. In contrast, DpnM can only methylate heterologous DNA in the form of dsDNA incorporated into the chromosome, a much smaller window of opportunity. Our findings confirm this interpretation by showing that DpnM-mediated protection is inefficient, since in the absence of DpnA, the vast majority of transformants are lost due to DpnII restriction (Fig. 3C). Moreover, competence induction of dpnM (i.e., to favor protection versus restriction) would be counter-productive for the cell, potentially increasing protection of me0 dsDNA phage and thus antagonizing the main role of DpnII. DpnA affords an elegant solution to this problem, as it provides protection to transformation intermediates via ss-methylation, but cannot antagonize DpnII-mediated phage destruction. Protecting long heterologous regions is of particular importance for the transfer of pathogenicity islands, such as the capsule locus which is generally considered the most important virulence factor of the pneumococcus. Capsule switching has been shown to be a prominent means of vaccine escape [20]. DpnA is likely to be crucial for DpnII cells to acquire serotypes from DpnI origin by transformation and, more generally, to allow evolution of the bacteria by acquisition and integration of foreign DNA.

As concerns the specific co-induction of dpnB with dpnA during competence, if DpnII concentration increase in competent cells is similar to that observed for DpnA, then clearly it pushes the DpnII/DpnM ratio toward restriction thus increasing the protection against dsDNA me0 bacteriophage, whilst maintaining the plasticity potential of the cell via DpnA.

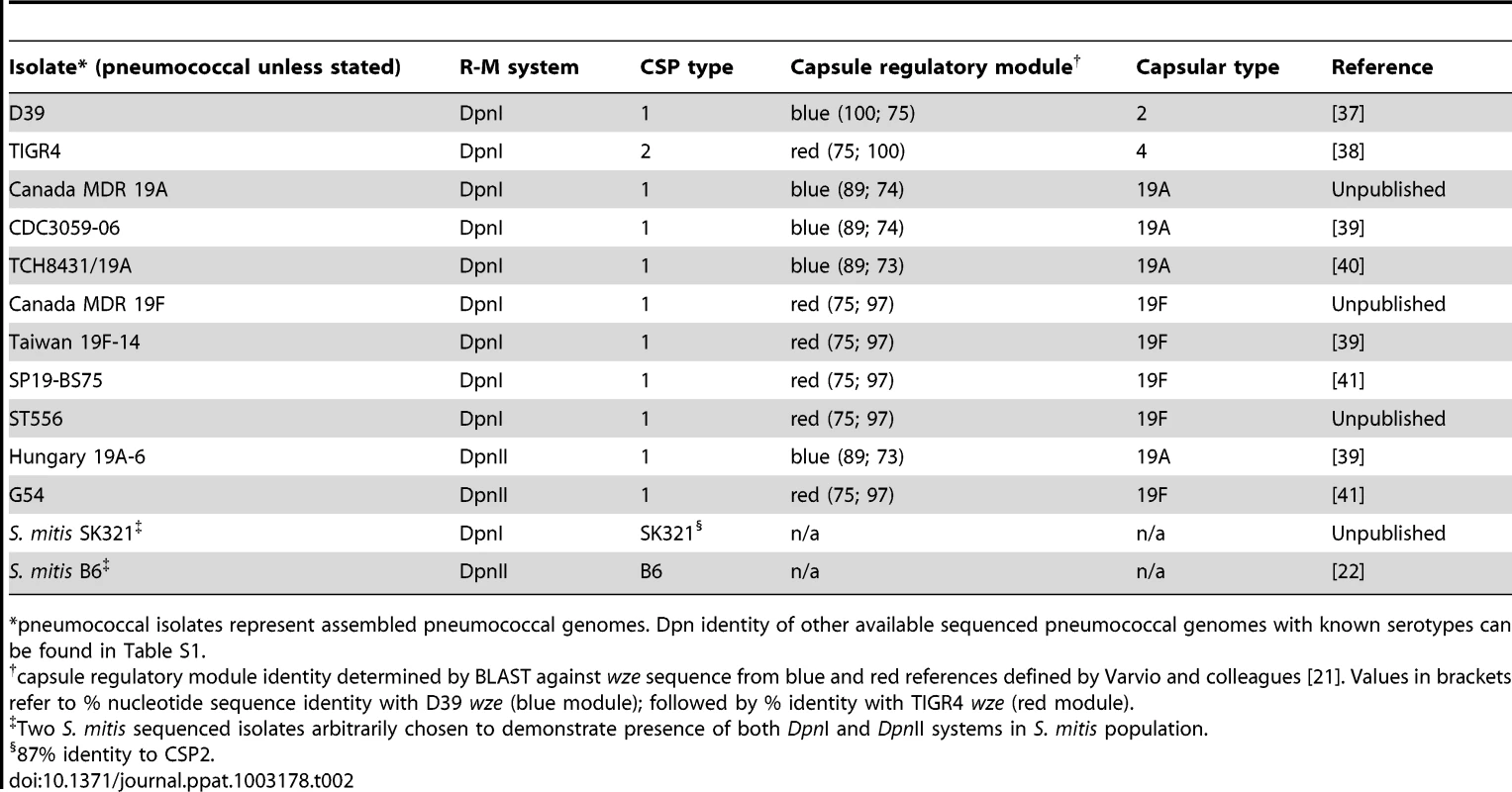

DpnI/DpnII R-M systems are not a barrier to genetic exchanges amongst pneumococci

The DpnI and DpnII R-M systems appear equally distributed in the pneumococcal population (Table 2). In the case of DpnI strains, no genetic barrier exists, as even when integrating me+ heterologous DNA (i.e., from DpnII), me+ dsDNA GATC sites are never produced in the host chromosome, which is never sensitive to DpnI restriction. In the case of DpnII strains, we have shown that DpnA protects heterologous me0 ssDNA, allowing acquisition of foreign pathogenicicy islands and preventing formation of a genetic barrier between the two populations. We would therefore predict that DpnI/DpnII R-M systems are not a barrier to genetic exchanges amongst pneumococci, i.e., that other variable loci such as capsular serotype [5], capsule regulatory module [21] or CSP pherotype [22] would be randomly distributed in the DpnI and DpnII populations. This prediction proved to be correct as evidenced by the 19A and 19F capsule serotypes in both Dpn types (Table 2). As a Dpn switch should be lethal, since expression of DpnI in a DpnII recipient would destroy the chromosome, and vice versa, we infer that the observed switches occurred in the other variable loci. The DpnI/DpnII split thus protects the pneumococcal species from both me+ and me0 bacteriophage, ensuring the survival of the pneumococcal species in the face of any bacteriophage attack, without creating an evolutionary barrier between the two sub-populations, thanks to the existence of and competence-induced production of DpnA.

Tab. 2. Presence of 19A and 19F serotypes in both DpnI and DpnII populations.

pneumococcal isolates represent assembled pneumococcal genomes. Dpn identity of other available sequenced pneumococcal genomes with known serotypes can be found in Table S1. ss-methylases in other species

Although methylases specific for ssDNA such as DpnA appear to be rare, a few others exist. Both DpnI and DpnII are present in Streptococcus mitis (our observations), a species closely-related to S. pneumoniae, and we propose that DpnB/DpnA play a similar dual role of protection from bacteriophage attack and maintenance of genetic exchange. Supporting this notion, the cin box in the PX dpnA promoter is perfectly conserved in a S. mitis DpnII strain [23] (our observations), suggesting that dpnA and dpnB form part of the competence regulon in this species as well. In Bacillus centrosporus, an analogous R-M system, BcnI, also possessing an ss-methylase, was identified [24]. If B. centrosporus were transformable, it would be interesting to investigate whether this ss-methylase plays a similar role to that of DpnA with respect to pathogenicicy/plasticity island exchange.

Impact of R-M systems on transformation in other species

Competence for genetic transformation is widespread in bacteria [2], although few studies have addressed the effect of R-M systems on genetic plasticity in these species. In the naturally transformable species Helicobacter pylori, R-M systems antagonize transformation, restricting genetic plasticity [25]. However, due to the internalization of exogenous DNA in ss form, the authors remained unclear as to the mechanism involved in this antagonization, and stated in a recent review ‘Because restriction enzymes prefer dsDNA, they likely act prior to unwinding and perhaps extracellularly’ [26]. Our model of DpnII-mediated restriction of transformant chromosomes formed after integration of me0 heterologous DNA (Fig. 1C) addresses this problem, highlighting the availability of fully sensitive me0 dsDNA in the transformant chromosome after replication, explaining how classical R-M systems can antagonize heterologous transformation. In contrast, we show that through programmed protection of foreign, heterologous me0 ssDNA by DpnA, the pneumococcal DpnII R-M system actively promotes genetic plasticity by favoring acquisition of heterologous me0 cassettes. This, along with the lack of identified ss-methylases in other transformable species, suggests that not all competent species have developed R-M systems that protect from bacteriophage attack, whilst at the same time maintaining the potential for genetic plasticity, and thus adaptation to environmental stresses by acquisition of virulence loci. It is likely that the need for such genetic flexibility is species-specific, since the pneumococcus, a pathogen and common commensal of humans constantly exposed to host, antibiotic and vaccine stresses, may need to maintain its propensity for rapid adaptation more so than another species occupying a different niche. The relative loss of genetic plasticity afforded by classic R-M systems may not be problematic for bacterial species that are not readily exposed to such selective pressures, and as such do not need to maintain a high level of genetic plasticity.

Alternative defense systems and maintenance of genetic exchanges

Other systems of defense against attack by foreign DNA exist, such as the clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat loci (CRISPR), which are sequence-specific defense mechanisms against bacteriophage, and have been shown to constitute a barrier to genetic diversity by horizontal gene transfer [27]. The pneumococcus does not possess CRISPR sequences, but a recent study artificially inserted CRISPR loci into the pneumococcal genome, and demonstrated that CRISPR interference blocked genetic plasticity by transformation in an in vivo model [28]. The authors concluded that CRISPR interference can limit the adaptability of a pathogen to a particular stress by limiting genetic plasticity. In contrast to our findings on the DpnII R-M system, no known mechanism exists to negate the antagonistic effect of CRISPR on genetic plasticity. Since we suggest that the pneumococcus appears to preferentially develop mechanisms that promote genetic diversity [3], the absence of CRISPR loci in this pathogen is not surprising. Indeed, despite the negative effect of CRISPR on genetic plasticity, the pneumococcus demonstrated the genetic flexibility required to spontaneously eject the CRISPR sequences when under environmental stress in the in vivo model, thus permitting a number of clones to adapt and survive [28]. It is unclear whether this ejection would be possible in bacteria that naturally possess CRISPR sequences, and do not favor adaptation by genetic plasticity to the same extent as the pneumococcus.

Bacterial pathogens must overcome two types of threat to survive and thrive, attack by foreign DNA (in the form of bacteriophage), and defenses mounted by host factors, antibiotics and vaccines. The pneumococcal DpnII system is an elegant system achieving both these ends. The DpnII restrictase protects the cell from me0 dsDNA bacteriophage attack, whilst the DpnA ss-methylase maintains the pneumococcus' extraordinary potential for genetic plasticity, allowing adaptation to and evasion of defenses, natural or artificial, mounted by the human host upon pneumococcal infection.

Concluding remarks

The question of why bacteria internalize exogenous DNA has been discussed at length [29]–[32]. The two credible suggestions are the use of DNA for genome maintenance via template-directed repair, or to promote genetic diversity via integration of exogenous DNA into the host genome. Here we show that competence induction of a locus coupling an ss-methylase to a restrictase is crucial for protection of heterologous exogenous DNA in the pneumococcus. We do not see how this protection could participate in genome maintenance, whereas it can clearly facilitate exchange of pathogenicity/plasticity islands. As a result, we consider this finding as the first direct evidence that S. pneumoniae can take up foreign DNA with the specific goal of integrating it into its chromosome via recombination, to promote genetic diversity.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth and transformation conditions

S. pneumoniae strain growth and transformation were carried out as described [33]. Strain, plasmid and primer information can be found in Table S2. Recipient strains were rendered hex− by insertion of the hexA::ermAM cassette as described [34], negating any effect of the mismatch repair system on transformation efficiencies [35]. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations; Chloramphenicol 4.5 µg mL−1, Erythromycin 2 µg mL−1, Kanamycin 250 µg mL−1, Spectinomycin 200 µg mL−1, Streptomycin 200 µg mL−1.

Replacement of dpnI locus by dpnII (with or without dpnA) in R800 background

The dpnI locus was replaced with the dpnII locus in laboratory strain R800 by Janus [36]. Briefly, the dpnI locus from R800 was amplified by PCR with primers dpnCup and dpnDdo, possessing BamHI and PstI restriction sites respectively, and cloned into pGBDU. The resulting plasmid (pGBDU-dpnI) was digested by ClaI and SacI restriction enzymes, deleting a 180 bp internal fragment of dpnC, encoding the DpnI restrictase. The Janus cassette was amplified with primers kan5c and 7 sac, possessing ClaI and SacI sites, and ligated into pGBDU-dpnC−, to give pGBDU-dpnI-Janus. The resulting plasmid was transformed into R981, with kanamycin selection, creating R2888. The Janus cassette was replaced with dpnII locus either wildtype (G54 donor DNA) or dpnA− (1135 donor DNA [13]) creating R2980 and R2981, respectively. The resulting strains were rendered SmS by transformation with a wild-type rpsL PCR fragment to remove the SmR point mutation rpsL1, creating R2992 and R2993, respectively.

Calculation of dpnA−/+ ratio

To calculate dpnA−/+ ratios, the transformation efficiency of a specific cassette into dpnA− and dpnA+ recipients was divided by the number of transformants by total number of colony forming units (cfu) obtained. This value was then normalized against a point mutation transformed on the same donor DNA (rpsL41, conferring SmR), unaffected by absence of DpnA. The resulting transformation efficiency for a dpnA− recipient was divided by the same value for the same cassette in a dpnA+ recipient to give the dpnA−/+ ratio. A ratio of 1 indicates no effect of absence of DpnA on transformation efficiency, whilst a ratio of <1 indicates a loss of transformation efficiency in a dpnA− recipient strain.

Miscellaneous methods

Further methods used in this study can be found in the Supporting Information. This file contains detailed descriptions of the cassettes used in this study, reporter fusions used to measure transcription of the PX promoter, creation of the cin− mutated dpnA promoter and construction of dpnA-SPA.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Maynard SmithJ, DowsonCG, SprattBG (1991) Localized sex in bacteria. Nature 349 : 29–31.

2. JohnsborgO, EldholmV, HåvarsteinLS (2007) Natural genetic transformation: prevalence, mechanisms and function. Res Microbiol 158 : 767–778.

3. ClaverysJP, PrudhommeM, Mortier-BarrièreI, MartinB (2000) Adaptation to the environment: Streptococcus pneumoniae, a paradigm for recombination-mediated genetic plasticity? Mol Microbiol 35 : 251–259.

4. CroucherNJ, HarrisSR, FraserC, QuailMA, BurtonJ, et al. (2011) Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science 331 : 430–434.

5. BentleySD, AanensenDM, MavroidiA, SaundersD, RabbinowitschE, et al. (2006) Genetic analysis of the capsular biosynthetic locus from all 90 pneumococcal serotypes. PLoS Genet 2: e31.

6. TockMR, DrydenDT (2005) The biology of restriction and anti-restriction. Curr Opin Microbiol 8 : 466–472.

7. LacksS, GreenbergB (1975) A deoxyribonuclease of Diplococcus pneumoniae specific for methylated DNA. J Biol Chem 250 : 4060–4066.

8. LacksSA, MannarelliBM, SpringhornSS, GreenbergB (1986) Genetic basis of the complementary DpnI and DpnII restriction systems of S. pneumoniae: an intercellular cassette mechanism. Cell 46 : 993–1000.

9. LeeMS, MorrisonDA (1999) Identification of a new regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae linking quorum sensing to competence for genetic transformation. J Bacteriol 181 : 5004–5016.

10. PetersonS, SungCK, ClineR, DesaiBV, SnesrudE, et al. (2004) Identification of competence pheromone responsive genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 51 : 1051–1070.

11. LacksSA, AyalewS, de la CampaAG, GreenbergB (2000) Regulation of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae: expression of dpnA, a late competence gene encoding a DNA methyltransferase of the DpnII restriction system. Mol Microbiol 35 : 1089–1098.

12. ClaverysJP, MartinB, PolardP (2009) The genetic transformation machinery: composition, localization and mechanism. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33 : 643–656.

13. CerritelliS, SpringhornSS, LacksSA (1989) DpnA, a methylase for single-strand DNA in the Dpn II restriction system, and its biological function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86 : 9223–9227.

14. BerryAM, GlareEM, HansmanD, PatonJC (1989) Presence of a small plasmid in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 65 : 275–278.

15. SiboldC, MarkiewiczZ, LatorreC, HakenbeckR (1991) Novel plasmids in clinical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 77 : 91–96.

16. SaundersCW, GuildWR (1981) Pathway of plasmid transformation in pneumococcus: open circular and linear molecules are active. J Bacteriol 146 : 517–526.

17. AttaiechL, OlivierA, Mortier-BarrièreI, SouletAL, GranadelC, et al. (2011) Role of the single-stranded DNA binding protein SsbB in pneumococcal transformation: maintenance of a reservoir for genetic plasticity. PLoS Genet 7: e1002156.

18. SallesC, CréancierL, ClaverysJP, MéjeanV (1992) The high level streptomycin resistance gene from Streptococcus pneumoniae is a homologue of the ribosomal protein S12 gene from Escherichia coli. Nucl Acids Res 20 : 6103.

19. HåvarsteinLS, CoomaraswamyG, MorrisonDA (1995) An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92 : 11140–11144.

20. BrueggemannAB, PaiR, CrookDW, BeallB (2007) Vaccine escape recombinants emerge after pneumococcal vaccination in the United States. PLoS Pathog 3: e168.

21. VarvioSL, AuranenK, ArjasE, MakelaPH (2009) Evolution of the capsular regulatory genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis 200 : 1144–1151.

22. HåvarsteinLS, HakenbeckR, GaustadP (1997) Natural competence in the genus Streptococcus: evidence that streptococci can change pherotype by interspecies recombinational exchanges. J Bacteriol 179 : 6589–6594.

23. DenapaiteD, BrucknerR, NuhnM, ReichmannP, HenrichB, et al. (2010) The genome of Streptococcus mitis B6–what is a commensal? PLoS ONE 5: e9426.

24. VilkaitisG, LubysA, MerkieneE, TiminskasA, JanulaitisA, et al. (2002) Circular permutation of DNA cytosine-N4 methyltransferases: in vivo coexistence in the BcnI system and in vitro probing by hybrid formation. Nucleic Acids Res 30 : 1547–1557.

25. HumbertO, DorerMS, SalamaNR (2011) Characterization of Helicobacter pylori factors that control transformation frequency and integration length during inter-strain DNA recombination. Mol Microbiol 79 : 387–401.

26. DorerMS, SesslerTH, SalamaNR (2011) Recombination and DNA repair in Helicobacter pylori. Annu Rev Microbiol 65 : 329–348.

27. MarraffiniLA, SontheimerEJ (2008) CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in taphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322 : 1843–1845.

28. BikardD, Hatoum-AslanA, MucidaD, MarraffiniLA (2012) CRISPR interference can prevent natural transformation and virulence acquisition during in vivo bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe 12 : 177–186.

29. DubnauD (1999) DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 53 : 217–244.

30. CharpentierX, PolardP, ClaverysJP (2012) Induction of competence for genetic transformation by antibiotics: convergent evolution of distant bacterial species lacking SOS? Curr Op Microbiol 15 : 570–6.

31. RedfieldRJ (2001) Do bacteria have sex? Nat Rev Genet 2 : 634–639.

32. ClaverysJP, PrudhommeM, MartinB (2006) Induction of competence regulons as general stress responses in Gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 60 : 451–475.

33. MartinB, PrudhommeM, AlloingG, GranadelC, ClaverysJP (2000) Cross-regulation of competence pheromone production and export in the early control of transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 38 : 867–878.

34. Mortier-BarrièreI, de SaizieuA, ClaverysJP, MartinB (1998) Competence-specific induction of recA is required for full recombination proficiency during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 27 : 159–170.

35. ClaverysJP, LacksSA (1986) Heteroduplex deoxyribonucleic acid base mismatch repair in bacteria. Microbiol Rev 50 : 133–165.

36. SungCK, LiH, ClaverysJP, MorrisonDA (2001) An rpsL Cassette, Janus, for Gene Replacement through Negative Selection in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl Environ Microbiol 67 : 5190–5196.

37. LanieJA, NgWL, KazmierczakKM, AndrzejewskiTM, DavidsenTM, et al. (2007) Genome Sequence of Avery's Virulent Serotype 2 Strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Comparison with That of Unencapsulated Laboratory Strain R6. J Bacteriol 189 : 38–51.

38. TettelinH, NelsonKE, PaulsenIT, EisenJA, ReadTD, et al. (2001) Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293 : 498–506.

39. DonatiC, HillerNL, TettelinH, MuzziA, CroucherNJ, et al. (2010) Structure and dynamics of the pan-genome of Streptococcus pneumoniae and closely related species. Genome Biol 11: R107.

40. NelsonKE, WeinstockGM, HighlanderSK, WorleyKC, CreasyHH, et al. (2010) A catalog of reference genomes from the human microbiome. Science 328 : 994–999.

41. HillerNL, JantoB, HoggJS, BoissyR, YuS, et al. (2007) Comparative genomic analyses of seventeen Streptococcus pneumoniae strains: insights into the pneumococcal supragenome. J Bacteriol 189 : 8186–8195.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 2- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Apoptogenic Toxin AIP56 Is a Metalloprotease A-B Toxin that Cleaves NF-κb P65

- Phylodynamic Analysis of the Emergence and Epidemiological Impact of Transmissible Defective Dengue Viruses

- Isolation of a Novel Swine Influenza Virus from Oklahoma in 2011 Which Is Distantly Related to Human Influenza C Viruses

- Using Existing Drugs as Leads for Broad Spectrum Anthelmintics Targeting Protein Kinases

- MCMV-mediated Inhibition of the Pro-apoptotic Bak Protein Is Required for Optimal Replication

- Neutrophils Exert a Suppressive Effect on Th1 Responses to Intracellular Pathogen

- -32 Ligand/Receptor Silencing Phenocopy Faster Plant Pathogenic Nematodes

- Targeted and Random Mutagenesis of for the Identification of Genes Required for Infection

- Noncanonical Inflammasomes: Caspase-11 Activation and Effector Mechanisms

- A Roadmap to the Human Virome

- Bacterial Survival Amidst an Immune Onslaught: The Contribution of the Leukotoxins

- Fifty Shades of Immune Defense

- Proteins Secreted via the Type II Secretion System: Smart Strategies of to Maintain Fitness in Different Ecological Niches

- Structural Determinants for Activity and Specificity of the Bacterial Toxin LlpA

- Protein Complexes and Proteolytic Activation of the Cell Wall Hydrolase RipA Regulate Septal Resolution in Mycobacteria

- Programmed Protection of Foreign DNA from Restriction Allows Pathogenicity Island Exchange during Pneumococcal Transformation

- Behavior of Prions in the Environment: Implications for Prion Biology

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Isolation of a Novel Swine Influenza Virus from Oklahoma in 2011 Which Is Distantly Related to Human Influenza C Viruses

- A Roadmap to the Human Virome

- Neutrophils Exert a Suppressive Effect on Th1 Responses to Intracellular Pathogen

- -32 Ligand/Receptor Silencing Phenocopy Faster Plant Pathogenic Nematodes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání