-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Steroid Catabolic Pathway of the Intracellular Pathogen Is Important for Pathogenesis and a Target for Vaccine Development

Rhodococcus equi causes fatal pyogranulomatous pneumonia in foals and immunocompromised animals and humans. Despite its importance, there is currently no effective vaccine against the disease. The actinobacteria R. equi and the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis are related, and both cause pulmonary diseases. Recently, we have shown that essential steps in the cholesterol catabolic pathway are involved in the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis. Bioinformatic analysis revealed the presence of a similar cholesterol catabolic gene cluster in R. equi. Orthologs of predicted M. tuberculosis virulence genes located within this cluster, i.e. ipdA (rv3551), ipdB (rv3552), fadA6 and fadE30, were identified in R. equi RE1 and inactivated. The ipdA and ipdB genes of R. equi RE1 appear to constitute the α-subunit and β-subunit, respectively, of a heterodimeric coenzyme A transferase. Mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔfadE30, but not RE1ΔfadA6, were impaired in growth on the steroid catabolic pathway intermediates 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD) and 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-5α-hydroxy-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1-indanone (5α-hydroxy-methylhexahydro-1-indanone propionate; 5OH-HIP). Interestingly, RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔfadE30, but not RE1ΔfadA6, also displayed an attenuated phenotype in a macrophage infection assay. Gene products important for growth on 5OH-HIP, as part of the steroid catabolic pathway, thus appear to act as factors involved in the pathogenicity of R. equi. Challenge experiments showed that RE1ΔipdAB could be safely administered intratracheally to 2 to 5 week-old foals and oral immunization of foals even elicited a substantial protective immunity against a virulent R. equi strain. Our data show that genes involved in steroid catabolism are promising targets for the development of a live-attenuated vaccine against R. equi infections.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002181

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002181Summary

Rhodococcus equi causes fatal pyogranulomatous pneumonia in foals and immunocompromised animals and humans. Despite its importance, there is currently no effective vaccine against the disease. The actinobacteria R. equi and the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis are related, and both cause pulmonary diseases. Recently, we have shown that essential steps in the cholesterol catabolic pathway are involved in the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis. Bioinformatic analysis revealed the presence of a similar cholesterol catabolic gene cluster in R. equi. Orthologs of predicted M. tuberculosis virulence genes located within this cluster, i.e. ipdA (rv3551), ipdB (rv3552), fadA6 and fadE30, were identified in R. equi RE1 and inactivated. The ipdA and ipdB genes of R. equi RE1 appear to constitute the α-subunit and β-subunit, respectively, of a heterodimeric coenzyme A transferase. Mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔfadE30, but not RE1ΔfadA6, were impaired in growth on the steroid catabolic pathway intermediates 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD) and 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-5α-hydroxy-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1-indanone (5α-hydroxy-methylhexahydro-1-indanone propionate; 5OH-HIP). Interestingly, RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔfadE30, but not RE1ΔfadA6, also displayed an attenuated phenotype in a macrophage infection assay. Gene products important for growth on 5OH-HIP, as part of the steroid catabolic pathway, thus appear to act as factors involved in the pathogenicity of R. equi. Challenge experiments showed that RE1ΔipdAB could be safely administered intratracheally to 2 to 5 week-old foals and oral immunization of foals even elicited a substantial protective immunity against a virulent R. equi strain. Our data show that genes involved in steroid catabolism are promising targets for the development of a live-attenuated vaccine against R. equi infections.

Introduction

Rhodococcus equi is a nocardioform Gram-positive bacterium and a facultative intracellular pathogen that causes fatal pyogranulomatous bronchopneumonia in young foals aged up to five months. R. equi is also an emerging opportunistic pathogen of immunocompromised humans, particularly HIV infected patients [1]–[3]. Like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB) in man, R. equi is able to infect, survive and multiply inside the host cells mainly in alveolar macrophages [4]–[7]. R. equi and M. tuberculosis are both members of the class of Actinomycetales and share physical, biochemical and cell biological characteristics [2]. Antibiotic treatment of R. equi infections is not consistently successful and is costly due to the necessity of treatment for a prolonged period of time [8]. More importantly, there is currently no safe and effective vaccine against R. equi infections.

Virulence of R. equi is dependent on the presence of a plasmid (approx. 85–95 kb) which is essential for R. equi to survive and grow in macrophages [9]–[13]. This virulence plasmid carries a pathogenicity island, encoding a number of related virulence associated proteins (Vaps) that includes the immunodominant surface expressed protein VapA [9], [10], [14]. Following infection with R. equi, the presence of the VapA-expressing virulence-associated plasmid is believed to promote necrotic damage to the host, which is strongly pro-inflammatory [15], [16]. VapA is not required for host cell necrosis, but has been implicated in early phagosome development [17]. Consistent with this role, mutational analysis showed that vapA, unlike vapG, is indispensable for multiplication of R. equi in macrophages and its persistence in mice [12], [18]. Indeed, VapA has been most widely investigated in vaccine studies for the prevention of R. equi infections. Oral vaccination of mice with an attenuated Salmonella enterica Typhimurium vaccine strain expressing VapA protein, for example, has been shown to confer protection against virulent R. equi [19], [20]. DNA vaccines encoding vapA have also been shown to stimulate cell-mediated immunity [21], [22].

Besides the vap genes, only a limited number of other virulence genes have been identified in R. equi to date. Random transposon mutagenesis using Himar1 transposition in R. equi identified a metabolic gene essential for riboflavin biosynthesis. The riboflavin auxotrophic mutant was shown to be fully attenuated in immunocompromised mice and could be safely administered to young foals [23], [24]. Immunization of young foals with the riboflavin auxotrophic mutant, however, did not afford protection against a virulent R. equi challenge [24]. choE, encoding the extracellular cholesterol oxidase in R. equi, is believed to be involved in macrophage destruction [25], but is not essential for virulence [26], [27]. Isocitrate lyase, a key enzyme of the glyoxylate bypass encoded by aceA, was shown to be important for virulence of R. equi. An aceA mutant was unable to proliferate in macrophages, was attenuated in mice and, when administrated to 3-week-old foals, did not induce pneumonic disease [28]. Crucially, a choE aceA double mutant in some cases was still able to induce severe pneumonia in 1-week-old foals, indicating that the mutant was not fully safe [27]. Attenuated mutants of R. equi were also obtained by targeted mutagenesis of htrA, narG, or pepD [29]. pepD in M. tuberculosis H37Rv is controlled by the two-component regulatory system MprA-MprB [30]. Consistent with this, the sensor kinase MprB of R. equi 103 was recently found to be required for intracellular survival [31]. So far, however, none of the strategies or identified virulence factors has resulted in the development of a safe vaccine capable of providing protective immunity against R. equi infection in young foals.

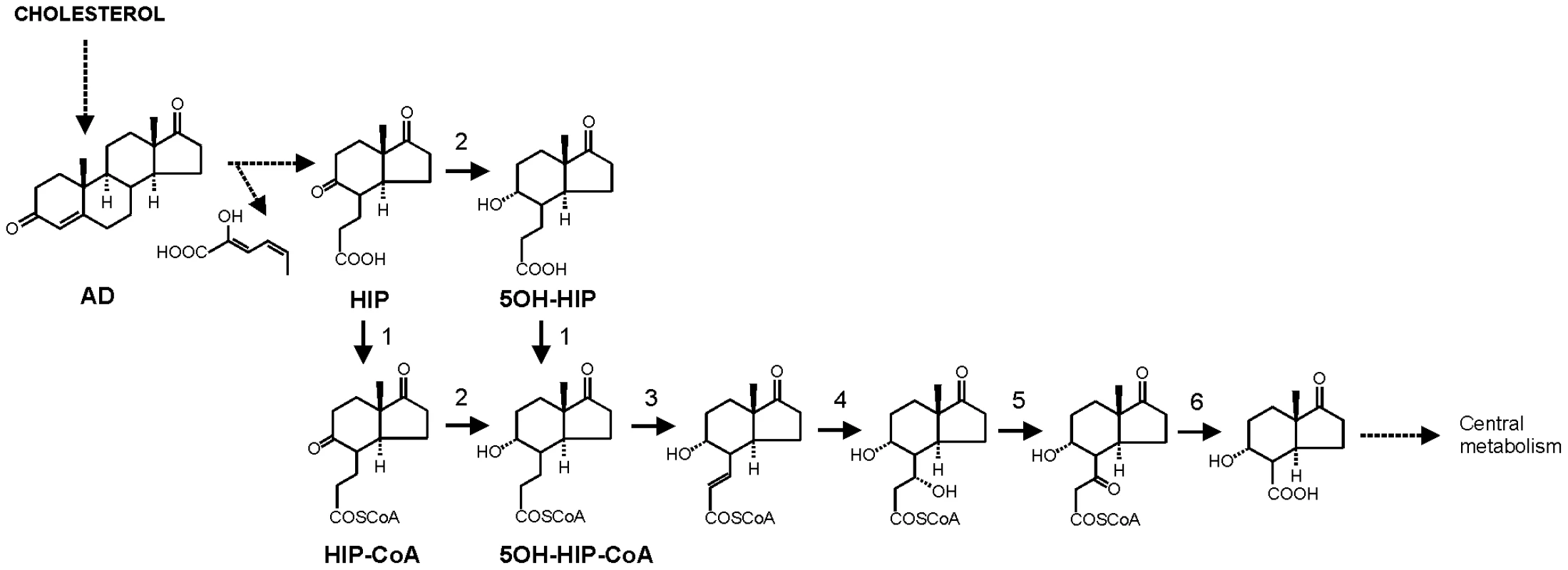

In addition to its pathogenic life-style, R. equi also thrives as a soil-dwelling microorganism capable of rapid growth in soil and manure using steroids, such as cholesterol, as sole carbon and energy sources [32]–[34]. Microbial steroid degradation of cholesterol proceeds via the formation of 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD), methylhexahydroindane-1,5-dione propionate (HIP; 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1,5-indanedione) and 5-hydroxy-methylhexahydro-1-indanone propionate (5OH-HIP) as pathway intermediates (Fig. 1) [35]–[36]. The cholesterol catabolic pathway has been implicated in the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis H37Rv [36]–[39]. Inactivation of the Mce4 cholesterol transporter in R. equi RE1, however, did not reveal an essential role of cholesterol catabolism in R. equi macrophage survival [34], [40]. Transposon mutagenesis had previously defined a subset of genes required for the survival of M. tuberculosis in murine macrophages. Amongst several others, rv3551 and rv3552 were predicted to be essential for the survival of M. tuberculosis H37Rv in vitro in macrophages [41]. Interestingly, rv3551 and rv3552 are part of the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster ([36]; Fig. S1). The close phylogenetic relationship between M. tuberculosis and R. equi prompted us to hypothesize that the predicted critically important genes of the cholesterol catabolic pathway in M. tuberculosis H37RV also are important for the pathogenicity of R. equi RE1. In this study, we identified the orthologs of rv3551 and rv3552, designated ipdA and ipdB, respectively, within the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster of R. equi 103S. The ΔipdAB mutant of R. equi RE1 was impaired in growth on the steroid catabolic pathway intermediates AD and 5OH-HIP. We also observed that RE1ΔipdAB was attenuated in vitro in macrophages. RE1ΔipdAB could be safely administered to 2–5 week-old foals intratracheally and oral immunization provided a substantial protection against R. equi infection. The data suggests that genes important for methylhexahydroindanone propionate (HIP, 5OH-HIP) degradation, as part of the steroid catabolic pathway, are promising targets for the development of a live-attenuated vaccine against R. equi infections.

Fig. 1. Proposed pathway of 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD) degradation via β-oxidation of methylhexahydroindanone propionate intermediates 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1,5-indanedione (HIP) and 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-5α-hydroxy-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1-indanone (5OH-HIP) by Rhodococcus equi.

Adapted from [35], [46]–[47]. Numbers represent the following proposed enzymatic steps of β-oxidation of HIP: 1) ATP dependent HIP-CoA transferase, 2) HIP-CoA 5-reductase, 3) acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, 4) 2-enoyl-CoA hydratase, 5) 3-hydroxyacyl-coA dehydrogenase, 6) 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. Dashed lines indicate multiple steps. Results

The R. equi 103S genome encodes two sets of genes orthologous to rv3551 and rv3552 of M. tuberculosis H37Rv

Bioinformatic analysis of the sequenced genome of R. equi 103S [42] revealed the presence of a cholesterol catabolic pathway (Fig. S1). Within the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster, two genes, i.e. ipdA (REQ_07170) and ipdB (REQ_07160), encode proteins that are highly similar to Rv3551 (69% identity) and Rv3552 (67% identity) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, respectively. The similarities of IpdA and IpdB are comparable to those observed between other homologous proteins of the cholesterol catabolic gene clusters of R. equi 103S and M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Table S1). The operonic structure of rv3551 and rv3552 in strain H37Rv was conserved in R. equi 103S (Fig. S1). Unlike H37Rv, the genome of R. equi 103S encoded a second set of paralogous proteins, designated IpdA2 and IpdB2, respectively, with highest protein sequence similarities to IpdA (55% identity) and IpdB (51% identity), respectively. This second set of genes, designated ipdA2 (REQ_00850) and ipdB2 (REQ_00860), was located outside of the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster and, unlike the ipdAB operon, was not clustered with an echA20 paralog.

IpdA carries the PF01144 signature motif of heterodimeric coenzyme A transferases (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk; [43]) as well as the COG1788 signature (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) of AtoD, the α subunit of acetoacetyl-CoA transferase of E. coli. Moreover, IpdB contained the COG2057 signature motif of AtoA, the β subunit of acetoacetyl-CoA transferase of E. coli. Highest overall amino acid sequence similarity of IpdA and IpdB with characterized proteins in databases was observed with ORF1 (41% identity) and ORF2 (36% identity) of Comamonas testosteroni TA441, representing the putative α and β subunits of a CoA-transferase, respectively, involved in testosterone catabolism [44]. Mutational analysis in C. testosteroni TA441 suggested that ORF1 is probably involved in the steroid degradation pathway at a step after ring cleavage into HIP and 2-hydroxyhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (Fig. 1; [44]). Since tesE, tesF and tesG are thought to encode the enzymes necessary to degrade 2-hydroxyhexa-2,4-dienoic acid [45], ORF1 is likely to play a role in HIP degradation. Thus, we hypothesized that IpdA and IpdB of R. equi most likely constitute the α-subunit and β-subunit, respectively, of a heterodimeric coenzyme A transferase involved in steroid catabolism, more specifically in methylhexahydroindanone propionate degradation.

R. equi mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 are impaired in steroid catabolism

To substantiate the predicted roles of ipdAB and ipdA2B2 in steroid catabolism, we constructed R. equi unmarked gene deletion mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB, RE1ΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 using the two-step homologous recombination strategy with 5-fluorocytosine counter-selection [34]. Deletion of the target genes ipdAB and/or ipdA2B2 was confirmed by PCR for all three mutant strains (Table S2, data not shown). PCR amplicons of the expected sizes were obtained for RE1ΔipdAB mutant (296 bp), RE1ΔipdA2B2 (123 bp) and RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 (296 bp and 123 bp, respectively). Analyses of the upstream and downstream regions of the deleted loci by PCR further confirmed genuine gene deletions and the absence of aberrant genomic rearrangements for all three mutants (Table S2). The presence of vapA as a marker for the virulence plasmid was also confirmed by PCR in each of the mutants (Table S2).

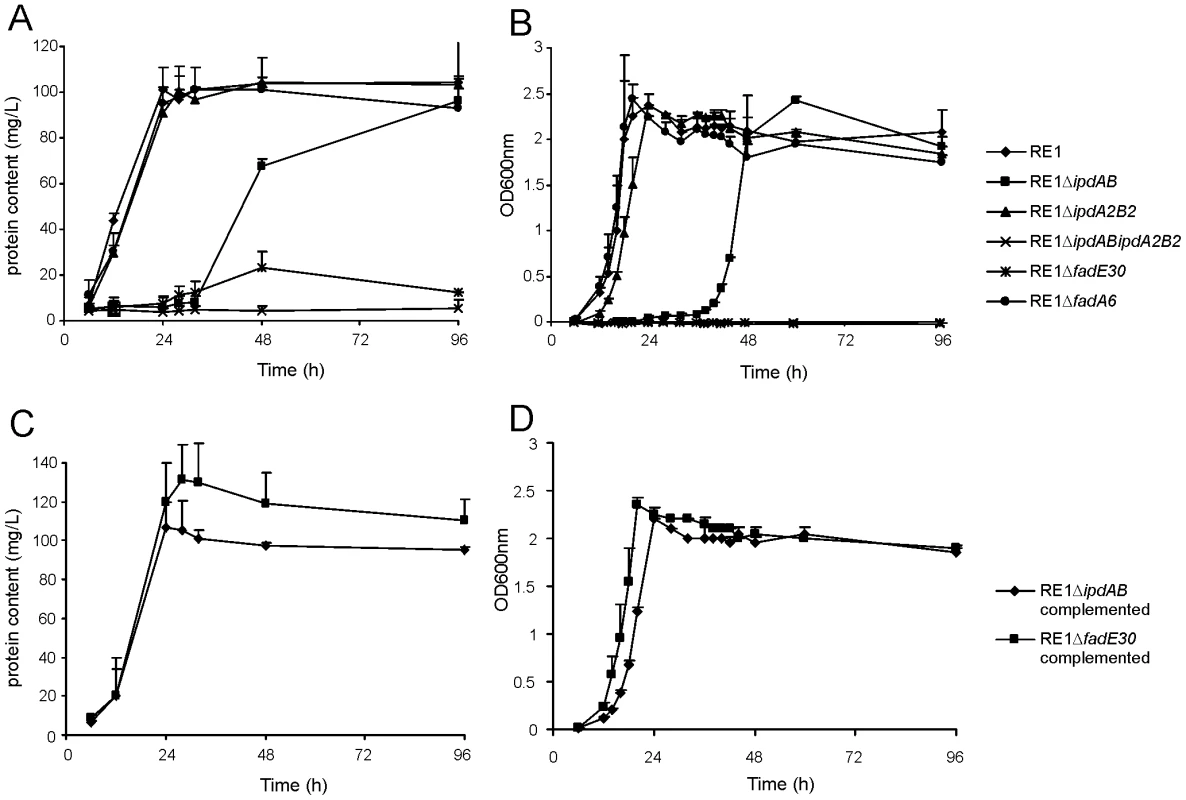

The growth of all three mutant strains on standard acetate mineral media was comparable to wild type strain RE1 (data not shown). Wild type strain RE1 also showed good growth on the steroid substrate AD as a sole carbon and energy source. By contrast, mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB was severely impaired in growth on AD (Fig. 2A). RE1ΔipdAB displayed an extensive lag-phase in growth of more than 24 h compared to wild type strain RE1. This growth phenotype of RE1ΔipdAB was fully complemented following the introduction of a 4,453 bp DNA fragment carrying wild type ipdAB under its native promoter (Table S2), restoring growth on AD to levels comparable to the wild type (Fig. 2C). Since RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 showed complete blockage of growth on AD, the observed growth of RE1ΔipdAB following the lag-phase appeared to be due to the presence of the paralogous gene set ipdA2B2 partly complementing the ipdAB mutation (Fig. 2A). RE1ΔipdA2B2 on the other hand was not impaired in growth on AD and grew comparably to wild type strain, indicating that ipdAB, located within the cholesterol gene cluster, is the dominant ipd gene set involved in steroid catabolism.

Fig. 2. Growth curves of wild type, mutant and complemented mutant strains of R. equi RE1 in mineral medium supplemented with 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD) or 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-5α-hydroxy-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1-indanone (5OH-HIP) as a sole carbon and energy source.

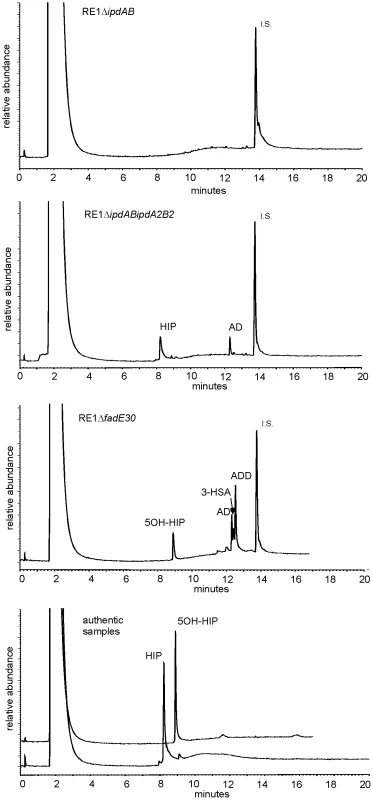

Panels A and B show growth curves of wild type strain (diamonds) and mutants strains RE1ΔipdAB (squares), RE1ΔipdA2B2 (triangles), RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 (crosses), RE1ΔfadE30 (asterisks) and RE1ΔfadA6 (circles) in MM+AD and MM+5OH-HIP, respectively. Panels C and D show growth curves of complemented strains of RE1ΔipdAB (diamonds) and RE1ΔfadE30 (squares) in MM+AD and MM+5OH-HIP, respectively. Curves represent averages of two independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations. Media with AD are turbid; therefore culture protein content was measured instead of optical density. Next, we investigated whether ipdAB and ipdA2B2 were involved in the catabolism of one of the predicted methylhexahydroindanone propionate intermediates of steroid degradation, i.e. 5OH-HIP (Fig. 2B). The growth phenotype of the mutants in the presence of 5OH-HIP as the sole carbon and energy source was comparable to those observed for AD: an extensive lag-phase in bacterial growth on 5OH-HIP was observed for strain RE1ΔipdAB, whereas hardly any impairment in growth was observed for RE1ΔipdA2B2. Finally, mutant strain RE1ΔipdABipdA2B2 displayed no growth on 5OH-HIP at all. To further substantiate the predicted involvement of ipdAB and ipdA2B2 in methylhexahydroindanone propionate degradation, we performed whole cell biotransformation experiments with cell cultures grown in mineral acetate medium and incubated with AD. Wild type strain RE1 fully degraded AD (0.5 g/l) within 24 hours without the accumulation of HIP or 5OH-HIP (data not shown). Accumulation of HIP from AD, however, was observed for mutant strain RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 (Fig. 3). A temporary accumulation of HIP, 24 hours after the addition of AD, was also detected in biotransformations with strain RE1ΔipdAB (data not shown). HIP formed by RE1ΔipdAB was, however, fully degraded after 120 hours of incubation (Fig. 3), consistent with its growth phenotypes on AD and 5OH-HIP. Thus, the ipdAB genes, encoding a heterodimeric CoA transferase in R. equi RE1, are important for growth on steroids and fulfil a role in the lower part of the steroid catabolic pathway, more specifically in methylhexahydroindanone propionate degradation.

Fig. 3. Gas chromatography profiles showing the formation of methylhexahydroindanone propionate intermediates during whole cell biotransformations of 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD) by mutant strains of R. equi RE1 at T = 120 hours.

Methylhexahydroindane-1,5-dione propionate (HIP) and 5-hydroxy-methylhexahydro-1-indanone propionate (5OH-HIP) accumulation in cell cultures of RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔfadE30, respectively. No accumulation is observed in cell cultures of RE1ΔipdAB. Lower panel shows the GC profiles of HIP (200 mg/L) and 5OH-HIP (50 mg/L) as authentic samples. Abbreviations: 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione (ADD), 3-hydroxy-9,10-secoandrost-1,3,5(10)-triene-9,17-dione (3-HSA), progesterone (50 mg/L) internal standard (I.S.). Inactivation of genes involved in methylhexahydroindanone propionate catabolism attenuates R. equi RE1 infection of macrophages

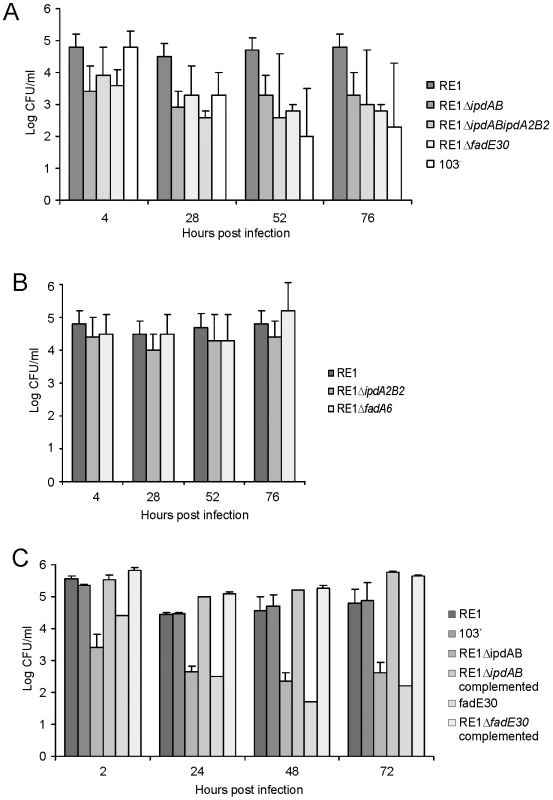

To investigate whether the ipdAB genes of R. equi RE1 are important for survival in macrophages, analogously to the predicted important role of rv3551 and rv3552 in M. tuberculosis H37Rv [41], in vitro macrophage infection assays were performed. Macrophage infection experiments showed that strain RE1ΔipdAB and strain RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 were significantly attenuated, comparable to the avirulent R. equi strain 103- lacking the virulence plasmid [10] (Fig. 4A). Control experiments with virulent wild type strain R. equi RE1 showed that the parent strain was able to infect macrophages (Fig. 4A). Inactivation of ipdAB was sufficient to significantly impair macrophage infection by R. equi RE1 and additional deletion of ipdA2B2 had no further attenuating effect (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this result, inactivation of ipdA2B2 alone did not result in attenuation, indicating that ipdAB is the dominant gene set involved in R. equi RE1 pathogenicity (Fig. 4B). The attenuation of RE1ΔipdAB was fully complemented by the introduction of wild type ipdAB (Fig. 4C), excluding the possibility that the attenuation was due to a mutation unrelated to ipdAB.

Fig. 4. Macrophage infection assays of the human monocyte cell line U937 with R. equi strains.

Macrophage cell suspensions were infected with wild type virulent strain R. equi RE1 or mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB, RE1ΔipdA2B2, RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2, RE1ΔfadE30 and RE1ΔfadA6. The numbers of intracellular bacteria were determined by plate counts in duplicate following macrophage lysis. The data represents the averages for at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations. Panel A shows the results for attenuated mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB, RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔfadE30. Avirulent strain R. equi 103- was used as a control. Panel B shows the results for non-attenuated mutant strains RE1ΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔfadA6. Statistically, mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB (P<0.02), RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 (P<0.01) and RE1ΔfadE30 (P<0.01) were significantly attenuated compared to parent strain RE1. Panel C shows the results (duplicates) with complemented mutant strains of RE1ΔfadE30 and RE1ΔipdAB. Wild type RE1, strain 103+, and mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔfadE30 were included as controls. To investigate whether other genes with a role in steroid catabolism are important for macrophage infection by R. equi RE1 we constructed additional gene deletion mutants. We chose to inactivate two other genes that were located in close proximity to ipdAB within the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster and had been predicted as important for survival of M. tuberculosis H37Rv in macrophages, i.e. fadE30 (REQ_07030) and fadA6 (REQ_07060) (Fig. S1; [36], [41]). Mutant strains RE1ΔfadA6 and RE1ΔfadE30 were subsequently tested for growth on AD and 5OH-HIP as sole carbon and energy sources. RE1ΔfadE30 was severely impaired in growth on AD and growth on 5OH-HIP was fully blocked (Fig. 2). The growth phenotype of RE1ΔfadE30 was fully complemented following the introduction of wild type fadE30 under its native promoter (Table S2), restoring growth on AD and 5OH-HIP to levels comparable to wild type (Fig. 2C and 2D). Consistent with the growth phenotypes of RE1ΔfadE30, cell cultures of mutant strain RE1ΔfadE30 accumulated 5OH-HIP during biotransformation of AD (Fig. 3). Thus, fadE30 plays an essential role in steroid catabolism at the level of methylhexahydroindanone propionate degradation. By contrast, RE1ΔfadA6 was not affected and able to rapidly grow on both 5OH-HIP and AD, comparable to parent strain RE1 (Fig. 2). This suggests that fadA6 of R. equi RE1 is not essential for AD and 5OH-HIP catabolism. However, further analysis revealed that the genome of R. equi 103S codes for an apparent paralog of FadA6 (REQ_21310) with 70% protein sequence identity. The possibility that fadA6 of RE1 is involved in steroid catabolism, but is not essential due to the presence of the gene paralog, therefore cannot be excluded at this point.

Macrophage infection assays revealed that strain RE1ΔfadE30 was significantly attenuated, comparable to that of the attenuated mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2, and the avirulent control strain R. equi 103- (Fig. 4A). The attenuation of RE1ΔfadE30 could be fully reversed by the introduction of wild type fadE30, indicating that attenuation was solely due to fadE30 gene inactivation (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, RE1ΔfadA6 was not attenuated and showed survival curves similar to parent strain RE1 (Fig. 4B), consistent with our hypothesis that R. equi RE1 mutant strains impaired in growth on methylhexahydroindanone propionate are attenuated.

Intratracheal challenge of foals revealed in vivo attenuation of mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB

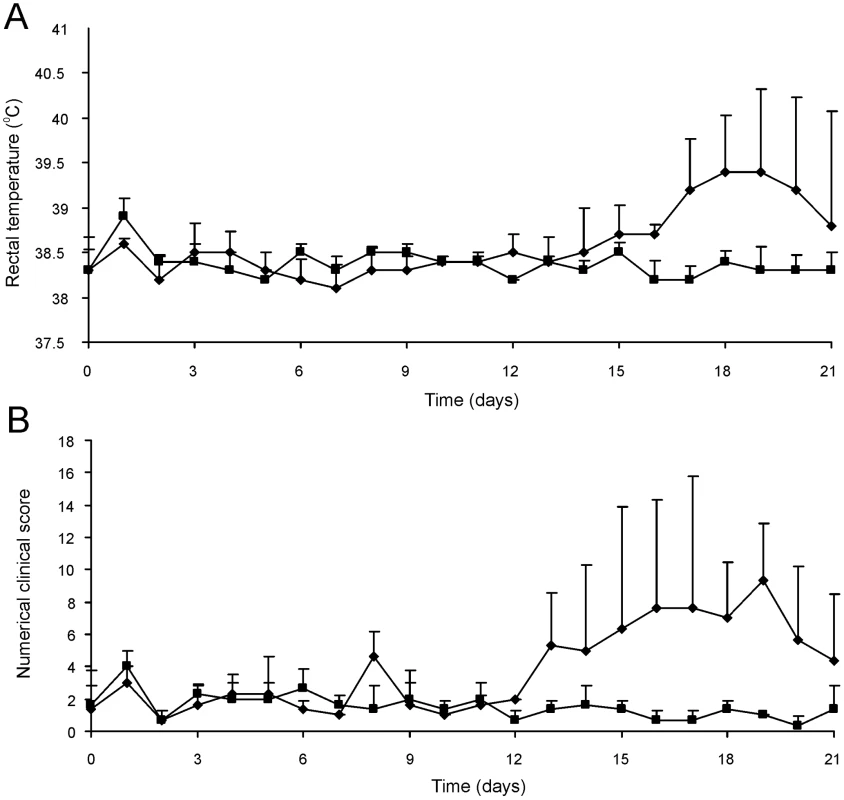

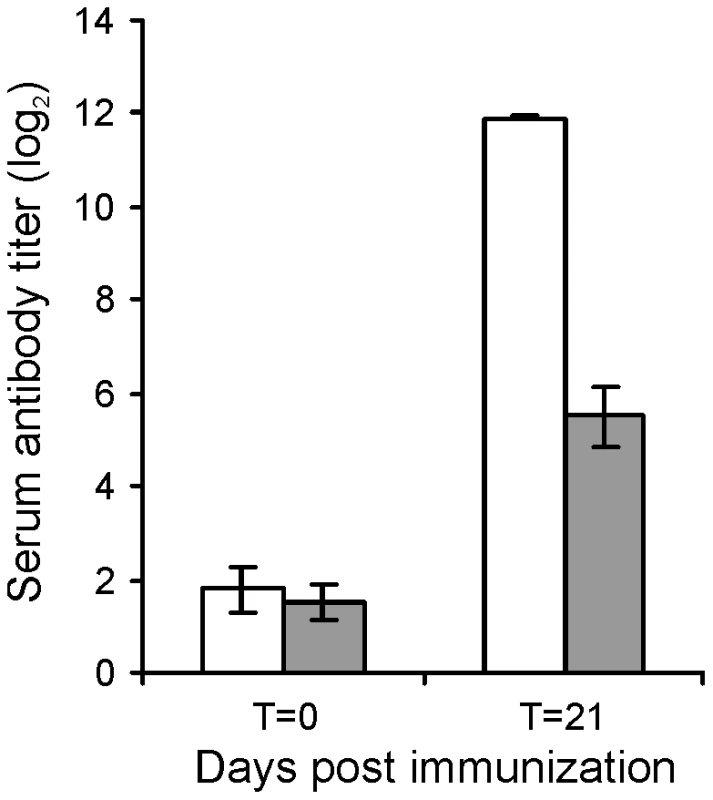

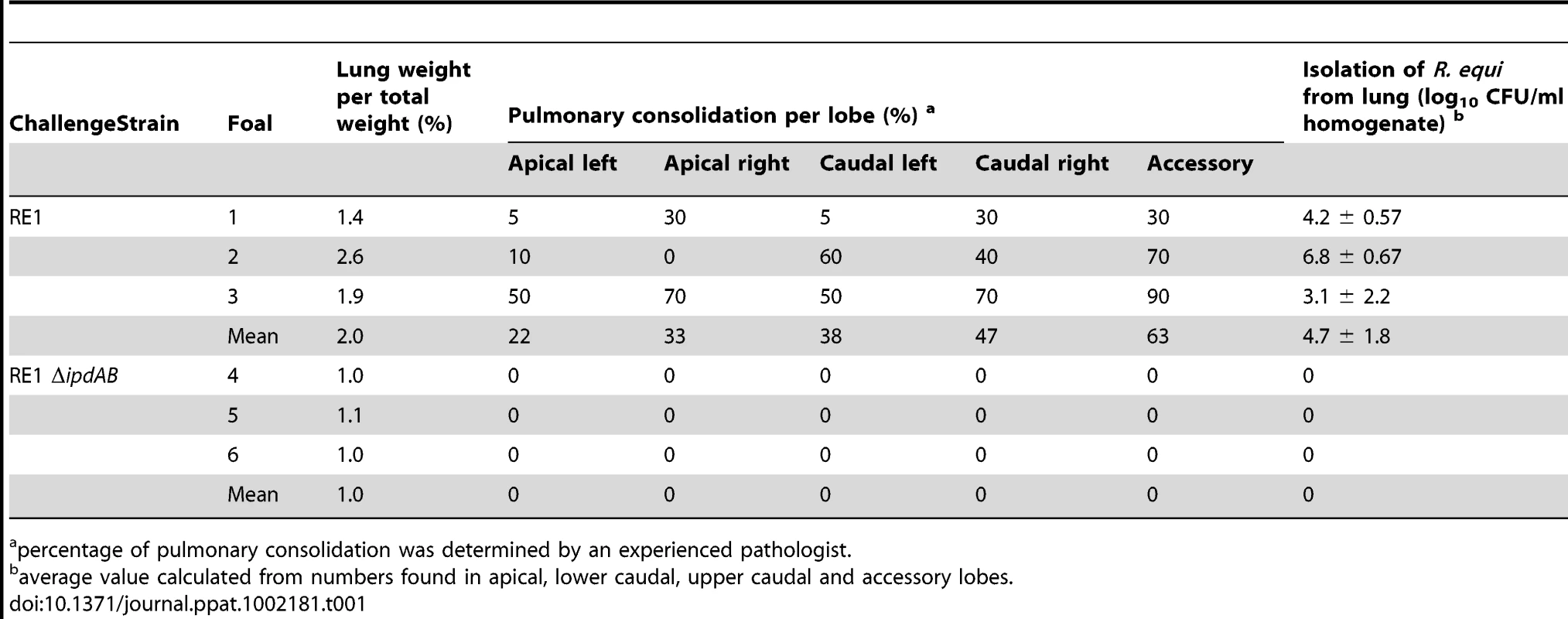

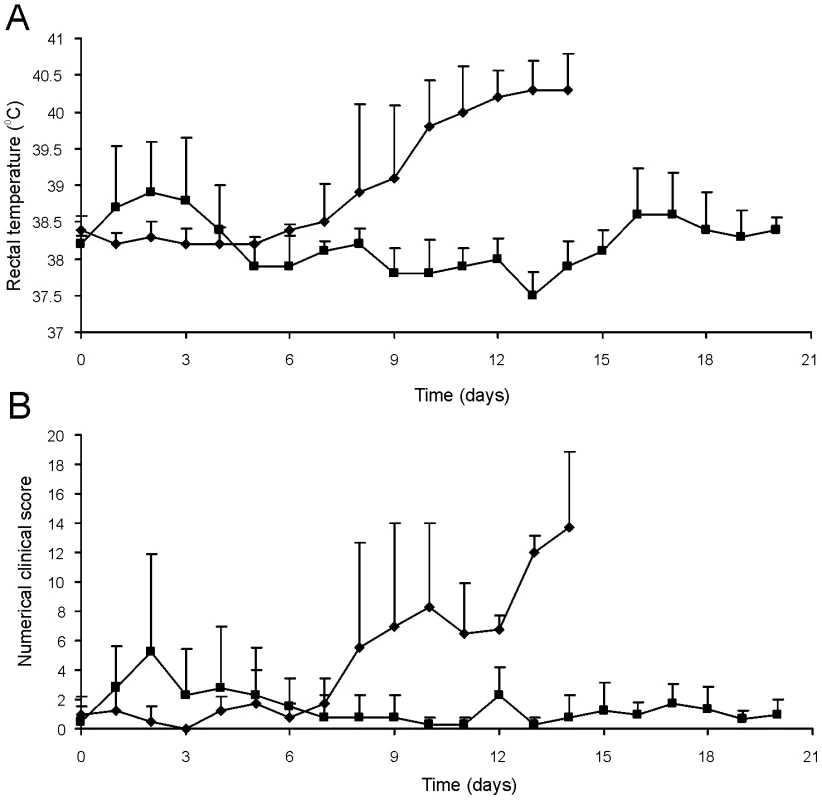

The attenuated phenotype of RE1ΔipdAB in our in vitro macrophage infection model suggested that strain RE1ΔipdAB also might be attenuated in foals. This prompted us to perform an in vivo intratracheal challenge experiment in young foals. In vivo attenuation of the RE1ΔipdAB mutant was tested in foals aged 3–5 weeks. The foals were equally divided into two groups of three (n = 3). One group was challenged intratracheally with mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB (7.1×106 CFU) and the other group with wild type strain RE1 (4.3×106 CFU) as a control. During a period of 3 weeks post-challenge the foals were clinically scored. None of the foals challenged with RE1ΔipdAB developed signs of respiratory disease and no increase in rectal temperatures of these foals was observed (Fig. 5). By contrast, two out of three foals in the wild type infected group developed severe clinical signs of respiratory disease, coinciding with increased rectal temperatures from 14 days post-challenge onwards. One wild type infected foal showed only mild clinical signs post-challenge. Mean daily weight gains post-challenge were substantially higher for foals challenged with RE1ΔipdAB (27.9 ± 5.2%) compared to those challenged with RE1 (18.9 ± 1.3%). Serum blood analyses revealed that the RE1ΔipdAB mutant strain was able to elicit a substantial serum antibody titer against R. equi, although the titers were lower than those observed in foals challenged with strain RE1 (Fig. 6). At 3 weeks post-challenge all foals were euthanized and subjected to a complete post-mortem examination. Foals challenged with wild type strain RE1 had developed typical pyogranulomatous pneumonia from which wild type R. equi successfully was re-isolated (Table 1). The lungs of the foals challenged with the mutant strain, on the other hand, did not reveal pneumonic areas and R. equi could not be isolated (Table 1). Consistent with these observations, the mean percentage lung-to-body weight of foals challenged with wild type RE1 (2.0 ± 0.6%) was twice as high as those challenged with mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB (1.0 ± 0.06%).

Fig. 5. Intratracheal challenge of 3 to 5-week-old foals. Foals (mean of n = 3) were challenged intratracheally with mutant R. equi RE1ΔipdAB (7.1×106 CFU; squares) or wild type RE1 (4.3×106 CFU; diamonds).

Panel A shows rectal temperatures. Panel B shows numerical clinical scores. Error bars represent standard deviation. Fig. 6. Serum antibody titer against R. equi of 3 to 5-week-old foals (n = 3) at day of intratracheal challenge (T = 0 days) and 3-weeks post-challenge (T = 21 days) with mutant R. equi RE1ΔipdAB (7.1×106 CFU; grey bars) or wild type RE1 (4.3×106 CFU; white bars).

Values represent mean ± standard deviation (error bars). Tab. 1. Pulmonary consolidation and re-isolation of R. equi of 3 to 5-week-old foals (n = 3) challenged intratracheally with wild type strain RE1 (4.3×106 CFU) or mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB (7.1×106 CFU).

percentage of pulmonary consolidation was determined by an experienced pathologist. Oral immunization of foals with RE1ΔipdAB provides substantial protection against an intratracheal challenge

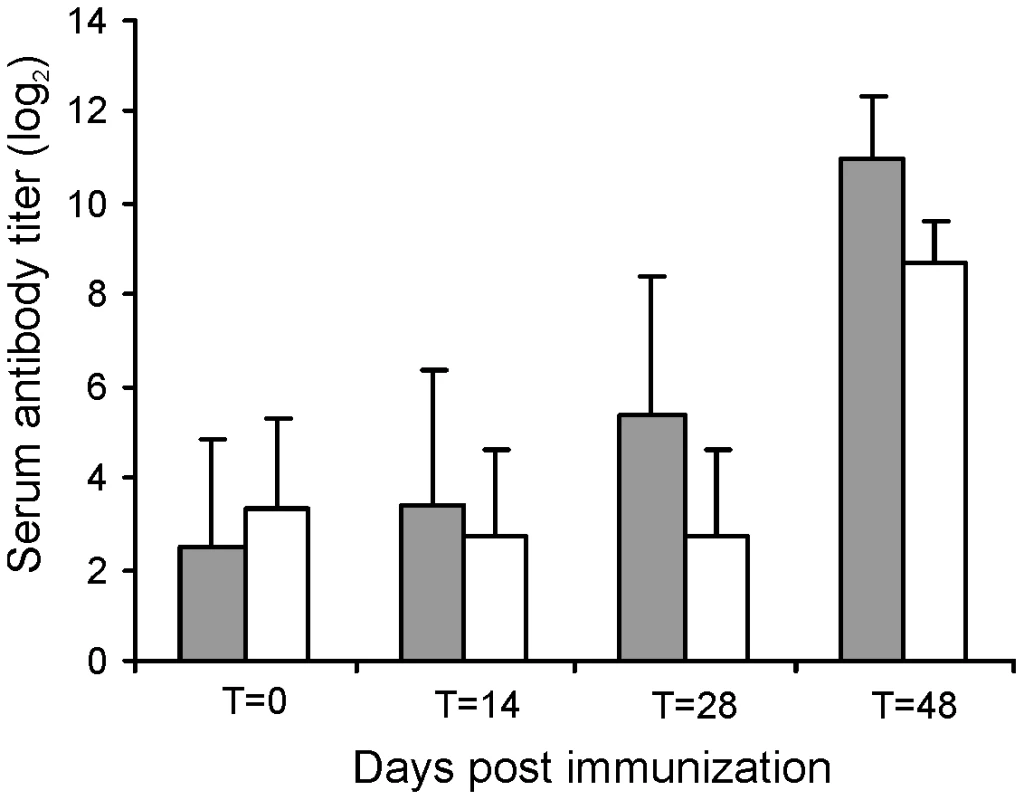

The challenge experiments indicated that RE1ΔipdAB was attenuated in young foals and able to induce an immunological response. To test RE1ΔipdAB as a live-attenuated vaccine-candidate in providing protective immunity against an intratracheal challenge with virulent R. equi, we performed an immunization experiment. Eight 2 to 4-week-old foals were used for this experiment and divided into two groups of four foals (n = 4). At T = 0 and at T = 14 days (booster) one group was vaccinated orally (1 ml) with strain RE1ΔipdAB (5×107 CFU/animal) and the other group was left as unvaccinated control. After vaccination, all foals remained healthy and no vaccine-related abnormalities were observed. Rectal temperatures remained normal in all foals (data not shown). Strain RE1ΔipdAB could not be re-isolated from rectal swabs, indicating that the mutant strain did not massively colonize the alimentary tract. Serum blood analyses revealed substantial serum antibody titers against R. equi following vaccination (Fig. 7). These post-vaccination results were consistent with the results obtained from the challenge experiment and confirmed that mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB was attenuated in vivo and can be safely administered to young foals.

Fig. 7. Serum antibody titer against R. equi of foals (n = 4) immunized orally (grey bars) at T = 0 and T = 14 days with attenuated R. equi strain RE1ΔipdAB (5×107 CFU) and challenged at T = 28 days with R. equi strain 85F (5×106 CFU).

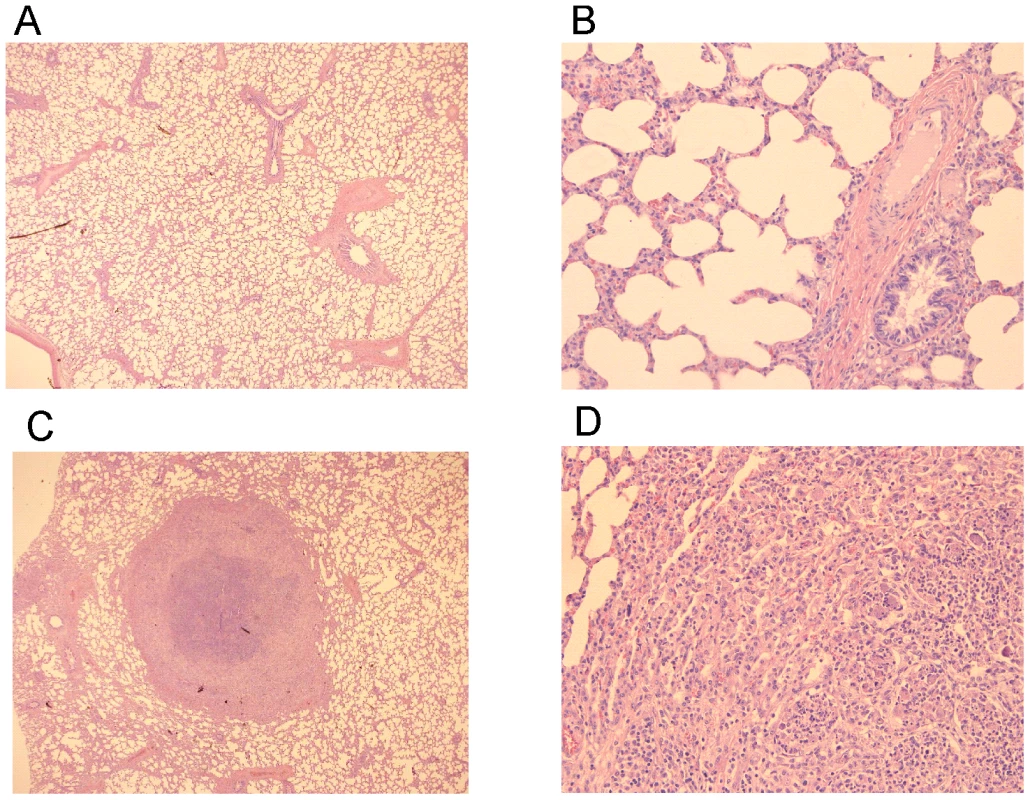

The serum antibody titer of unvaccinated control foals (n = 4) are shown in white bars. Bars represent mean titers at day of vaccination (T = 0), at day of booster vaccination (T = 14), at day of intratracheal challenge (T = 28) and 20 days post-challenge (T = 48). Error bars represent standard deviation. All foals were subsequently challenged intratracheally with virulent strain R. equi 85F (5×106 CFU), displaying strong cytotoxicity [16], two weeks after the booster vaccination (T = 28 days). During a period of 3 weeks post-challenge the foals were clinically scored. Then foals were euthanized and subjected to a complete post-mortem examination with special attention to the lungs and respiratory lymph nodes as well as the gut and associated lymph nodes. All four foals in the control group showed increasing signs of respiratory disease from day 7 to 10 post-challenge onwards (Fig. 8; T = 35–38 days). The control foals were euthanized 14 days post challenge (T = 42 days) for humane reasons. Post-mortem macroscopic and microscopic analysis confirmed pyogranulomatous pneumonia in the control foals with severe pulmonary consolidations from which wild type R. equi was re-isolated as identified by PCR (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 9). Wild type R. equi was also isolated in high numbers from swollen mediastinal lymph nodes and in one foal from a caecal lymph node. By contrast, the vaccinated foals had much milder clinical signs or virtually no clinical signs at all (Fig. 8). Two vaccinated foals remained completely healthy and post-mortem macroscopic analysis did not reveal any signs of pyogranulomatous pneumonia. Two other vaccinates had locally developed pyogranulomatous pneumonia with pulmonary consolidations in the accessory and caudal lobes from which wild type R. equi was isolated (Tables 2 and 3). Overall, the numbers of wild type R. equi isolated from the lungs of the vaccinated foals were substantially lower than those found in the control group. We conclude that vaccination of young foals with strain RE1ΔipdAB is safe and induces a substantial protective immunity against a severe intratracheal challenge with a virulent R. equi strain.

Fig. 8. Oral immunization and subsequent intratracheal challenge of foals.

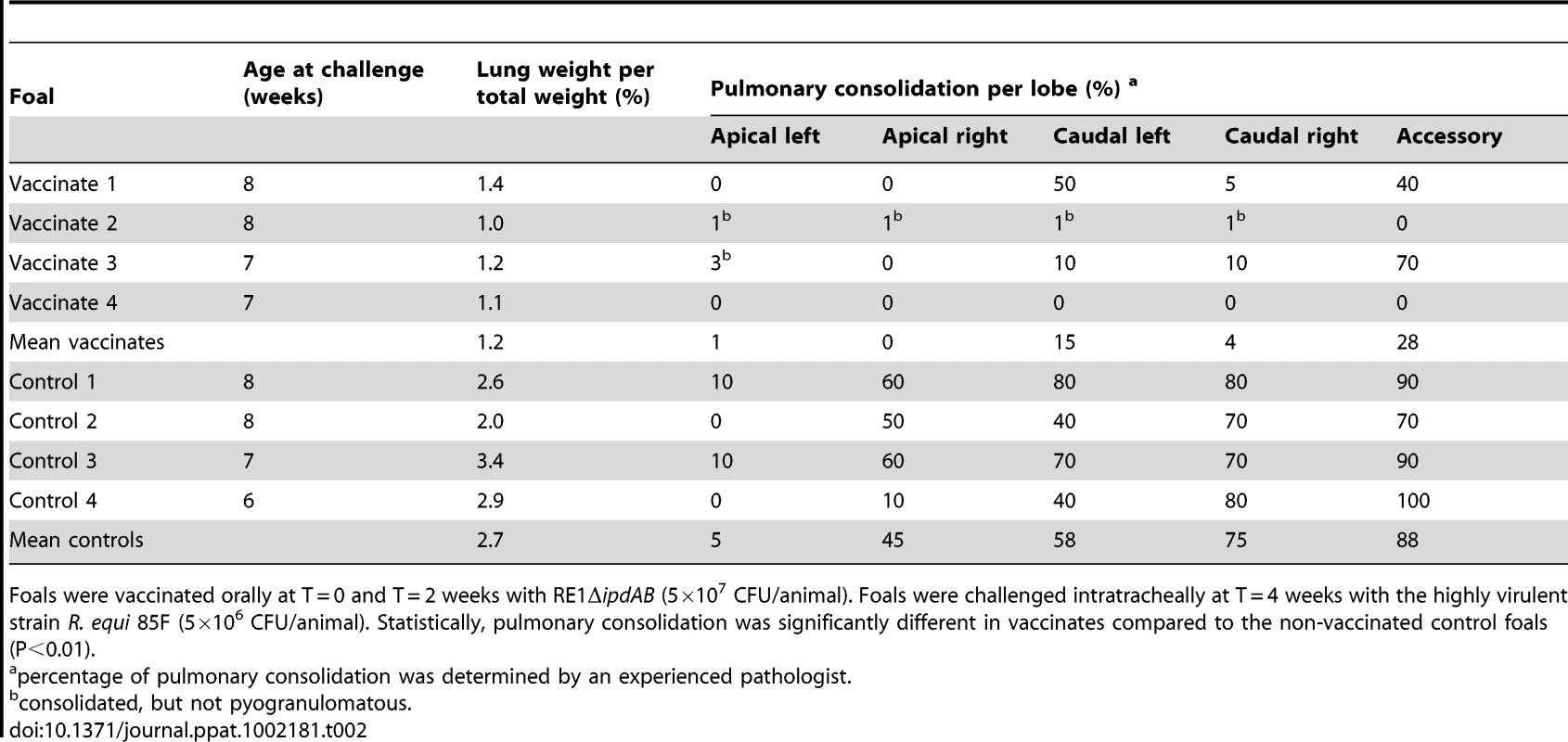

Foals (2 to 4-week-old) vaccinated with RE1ΔipdAB (squares) and non-vaccinated controls (diamonds) (mean of n = 4) were challenged intratracheally with virulent strain R. equi 85F (5×106 CFU). Panel A shows rectal temperatures. Panel B shows numerical clinical scores. Statistically, rectal temperatures (P<0.005) and clinical scores (P<0.0001) were significantly different in vaccinates compared to the non-vaccinated control foals. Error bars represent standard deviation. Fig. 9. Histopathology of lung tissue of vaccinates versus non-vaccinated foals following intratracheal challenge with wild type R. equi.

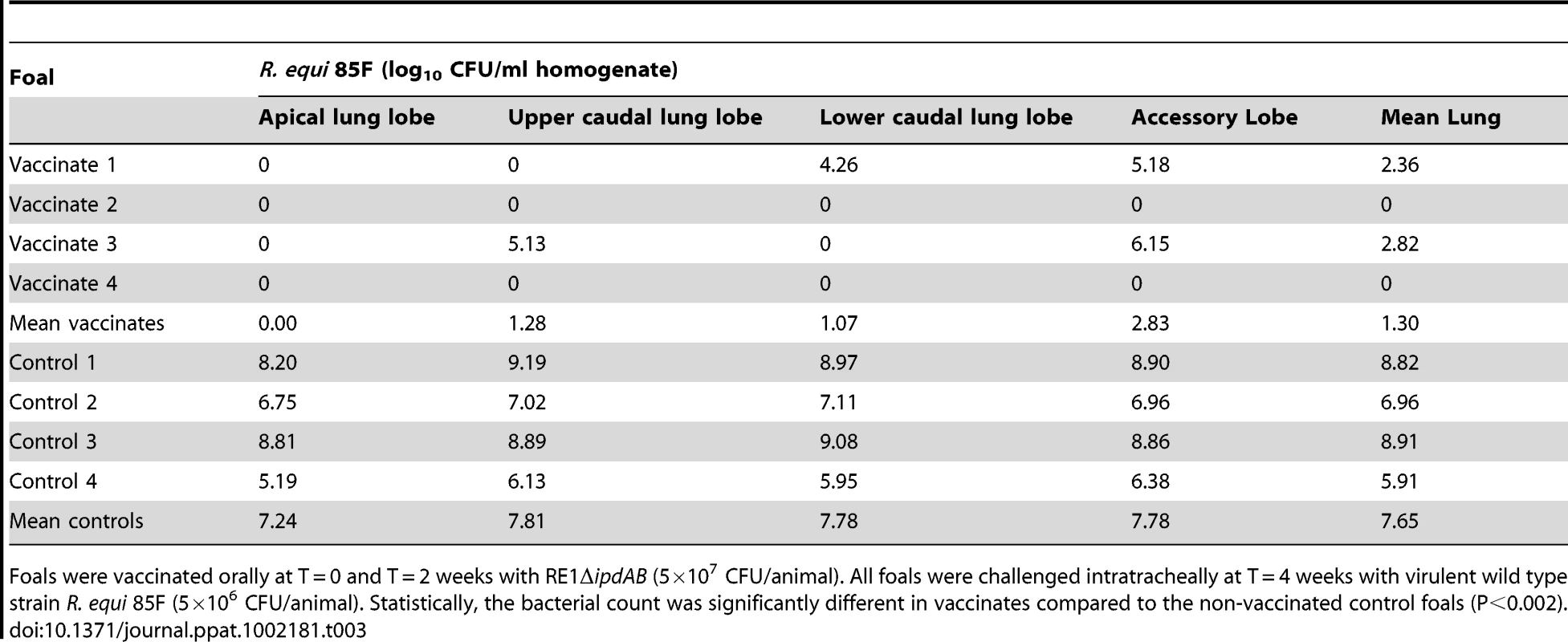

Lung specimen of a vaccinated foal showing normal airways (bronchi and bronchioli), blood vessels and alveoli at (A) 25x and (B) 200x magnification. Typical pyogranuloma (5 mm diameter) observed in lung specimens of non-vaccinated control foals at (C) 25x and (D) 200x magnification. The centre of the pyogranuloma consists of necrotic debris, neutrophils and toxic neutrophils with complete loss of lung architecture. Tab. 2. Lung weights and percentage pulmonary consolidation per lobe of vaccinated and unvaccinated (control) 2 to 4-week-old foals (n = 4).

Foals were vaccinated orally at T = 0 and T = 2 weeks with RE1ΔipdAB (5×107 CFU/animal). Foals were challenged intratracheally at T = 4 weeks with the highly virulent strain R. equi 85F (5×106 CFU/animal). Statistically, pulmonary consolidation was significantly different in vaccinates compared to the non-vaccinated control foals (P<0.01). Tab. 3. Quantitative re-isolation of R. equi 85F from lung lobes of vaccinated and unvaccinated (control) 2 to 4-week-old foals (n = 4).

Foals were vaccinated orally at T = 0 and T = 2 weeks with RE1ΔipdAB (5×107 CFU/animal). All foals were challenged intratracheally at T = 4 weeks with virulent wild type strain R. equi 85F (5×106 CFU/animal). Statistically, the bacterial count was significantly different in vaccinates compared to the non-vaccinated control foals (P<0.002). Discussion

The current study identified the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster in R. equi and showed that ipdAB and fadE30 located within this cluster are important for the pathogenicity of R. equi RE1. Interestingly, R. equi RE1 mutants that displayed attenuated phenotypes in an in vitro macrophage infection assay were also impaired in steroid catabolism, i.e. RE1ΔipdAB, RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔfadE30. Conversely, mutants that had AD growth phenotypes comparable to wild type strain RE1, i.e. RE1ΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔfadA6, were not attenuated. Both fadE30 and ipdAB were also shown to be important for 5OH-HIP catabolism. Biochemical and physiological studies previously showed that the degradation of the propionate moiety of HIP and 5OH-HIP likely occurs via a cycle of β-oxidation [35], [46]–[47] (Fig. 1). ATP-dependent CoA activation was suggested to be the first step in the degradation of HIP in R. equi ATCC14887 [46]. Protein sequence analysis revealed that IpdA and IpdB represent the α and β-subunit of a heterodimeric CoA-transferase. The heterodimeric CoA-transferase encoded by ipdAB thus might be involved in the removal of the propionate moiety of methylhexahydroindanone propionate intermediates (i.e. HIP, 5OH-HIP) by β-oxidation during steroid degradation (Fig. 1, step 1). Consistent with such a role, HIP accumulation was observed in biotransformation experiments with cell cultures of RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 incubated with AD (Fig. 3). FadE30 belongs to the family of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and might catalyze the second step in the β-oxidation cycle that removes the propionate moiety following CoA activation by IpdAB, i.e. the dehydrogenation of 5OH-HIP-CoA (Fig. 1, step 3). Accumulation of 5OH-HIP indeed was observed in biotransformation experiments with cell cultures of RE1ΔfadE30 incubated with AD (Fig. 3). Interestingly, ipdA and ipdB appear to be part of an operon encompassing echA20 (Fig. S1), encoding a putative enoyl-coA hydratase that might catalyse the subsequent step in the β-oxidation cycle during the degradation of the propionate moiety (Fig. 1, step 4). However, functions of ipdAB, fadE30 and echA20 further down in the degradation pathway of these compounds cannot be excluded and need further investigation.

A second set of paralogous genes, designated ipdA2 and ipdB2, was additionally identified in R. equi RE1 which do not play an important role in AD or 5OH-HIP catabolism. Still, ipdA2B2 are involved in growth on AD and 5OH-HIP, since ipdA2B2 are able to support the growth of mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB on AD and 5OH-HIP, albeit after an extensive lag-phase (Fig. 2). The data suggests that the primary role of ipdA2B2 is not in AD or 5OH-HIP catabolism, but that they are recruited in the ΔipdAB mutant, perhaps through a genetic mutation. Protein sequence similarities between IpdA and IpdA2 and between IpdB and IpdB2 are relatively low, which suggests that IpdAB and IpdA2B2 are related proteins, but have different physiological functions. This is further supported by the genomic location of ipdA2 and ipdB2 in a region distant from the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster and with no apparent clustering of steroid genes. Consistently, ipdA2B2 does not appear to be involved in pathogenesis. Due to the likely different physiological function of ipdA2B2 in R. equi these genes may be expressed differently relative to ipdAB, or even not at all, during R. equi infection.

Overall, our results strongly imply that the pathogenicity of R. equi correlates with the steroid catabolic pathway, in particular with methylhexahydroindanone propionate (HIP, 5OH-HIP) degradation. Several other examples of virulence-associated genes important for microbial steroid ring degradation have been reported. The kshA and kshB genes of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, for example, were shown to be essential for pathogenicity of H37Rv [39]. These genes encode the two-component iron-sulfur protein 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase, which is a key-enzymatic step in microbial steroid ring opening [48]. The steroid ring-cleaving dioxygenase HsaC, catalyzing the further breakdown of steroids towards methylhexahydroindanone propionate pathway intermediates, also contributes to the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis H37Rv [38]. We do not yet understand why genes of the steroid catabolic pathway are important for the pathogenicity of R. equi. Considering that many steroids are known to have immuno-regulatory properties, steroids could play an important role during R. equi infection. In vivo, β-androstenes, such as 3β-hydroxy-5-androstene-17-one (DHEA) and 5-androstene-3β,17β-diol, have been associated with immune-homeostasis during bacterial infection [49]. Thus, ipdAB, fadE30 and other genes involved in steroid ring degradation may help R. equi to disrupt the immune-homeostasis in a yet unknown way, favouring infection of the macrophage. Intriguingly, attenuated mutant strains RE1ΔipdAB, RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 and RE1ΔfadE30 consistently showed significantly lower bacterial counts in our macrophage infection assay at T = 4 h post-infection (Fig. 4A) compared to wild type strains RE1 and avirulent strain 103−, which suggests that the attenuated mutants are affected in processes that occur early in the infection. Whether these processes are involved in immune-homeostasis or are related to some other process, such as impaired adherence or uptake of R. equi by the macrophage, remains to be elucidated.

It is noteworthy to mention that, for reasons unknown, wild type R. equi strains RE1 and 103+ do not appear to replicate well in the human macrophage cell line U937 when compared to the replication of wild type R. equi in murine or equine primary macrophages.

A subset of genes of the cholesterol gene cluster present in Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155, designated the kstR2 regulon, was recently shown to be controlled by the TetR-type transcriptional regulator kstR2 [50]. An apparent orthologue of kstR2 of M. smegmatis mc2155 was also found present in the cholesterol gene cluster of R. equi 103S, encoding a protein with 56% amino acid sequence identity and located between fadE30 and fadA6 (Fig. S1). Interestingly, the fadA6, fadE30 and ipdAB orthologues in M. smegmatis mc2155 all are part of the kstR2 regulon [50]. Most likely, the kstR2 regulon of M. smegmatis mc2155 is involved in methylhexahydroindanone propionate catabolism. The presence of a putative kstR2 regulon in R. equi 103S raises the intriguing question whether all genes belonging to this regulon are important for R. equi pathogenicity.

Several vaccination strategies have been explored to date in an attempt to prevent infection by the opportunistic horse pathogen R. equi. So far, these have not resulted in the development of a safe and effective vaccine against R. equi infection. Indeed, protection has been observed when wild type virulent R. equi was administrated orally [51]–[53]. However, this vaccination approach cannot be used due to the high risk of provoking disease and contamination of the environment. Immunization procedures using avirulent (plasmid-less) or killed R. equi cells, on the other hand, do not induce a protective immune response [52] and underline the importance of developing a live-attenuated vaccine strain. The administration of specific hyperimmune plasma currently has been the only method providing a positive effect in avoiding foals of an endemic farm to develop R. equi pneumonia [54]–[56]. The method, however, is expensive, labour intensive and not consistently effective [57]–[59]. Our strategy targeted genes in the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster of R. equi to develop a live-attenuated vaccine. Our data revealed that RE1ΔipdAB is a highly promising candidate for a live-attenuated vaccine strain providing substantial protective immunity. Full immunity following oral immunization with RE1ΔipdAB was not yet observed in the vaccination experiment, since two foals showed mild signs of pneumonic disease following a severe challenge with R. equi 85F (Tables 2 and 3). However, re-isolation of wild type R. equi was several log10 fold lower in lungs of immunized foals compared to those of non-vaccinated controls (Table 3), strongly suggesting that protection had not yet fully developed. Further optimization of the vaccination protocol to increase its efficacy, as well as field trials, is currently on the way to develop the first safe and effective live-attenuated vaccine against R. equi infection in young foals.

The incidence of R. equi infection in humans has increased markedly with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, as well as with the development of organ transplantations and chemotherapy for malignancies [1], [60]–[61]. The infection mortality rate is still high (20–25%), especially for AIDS patients (50–55%), and disease relapses are common [60], [62]. The steroid catabolic pathway of R. equi therefore may provide interesting novel targets for drug development to treat R. equi infection in humans, as many of the catabolic enzymes have no human homolog.

Materials and Methods

Culture media and growth conditions

R. equi RE1 was isolated from a foal with pyogranulomatous pneumonia in the Netherlands in September 2007 [34]. Strains R. equi 103+ [14], R. equi 103− [63] and R. equi 85F [52], [64] have been previously described. R. equi cell cultures were routinely grown at 30°C (200 rpm) in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium consisting of Bacto-Tryptone, Yeast Extract and 1% NaCl, or mineral acetate medium (MM-Ac) containing K2HPO4 (4.65 g/l), NaH2PO4·H2O (1.5 g/l), sodium acetate (2 g/l), NH4Cl (3 g/l), MgSO4·7H2O (1 g/l), thiamine (40 mg/l, filter sterile), and Vishniac stock solution (1 ml/l). Vishniac stock solution was prepared as follows (modified from Vishniac and Santer [65]): EDTA (10 g/l) and ZnSO4.7H2O (4.4 g/l) were dissolved in distilled water (pH 8.0 using 2 M KOH). Then, CaCl2.2 H2O (1.47 g/l), MnCl2.7 H2O (1 g/l), FeSO4.7 H2O (1 g/l), (NH4)6 Mo7O24.4 H2O (0.22 g/l), CuSO4.5 H2O (0.315 g/l) and CoCl2.6 H2O (0.32 g/l) were added in that order maintaining pH at 6.0 and finally stored at pH 4.0. For growth on 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD, 0.5 g/l) or 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-5α-hydroxy-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1-indanone (5OH-HIP, 1 g/l) as sole carbon and energy source sodium acetate was omitted from the medium. Stock solutions of 5OH-HIP (100 mg/ml), prepared by dissolving 100 mg 3aα-H-4α(3′-propionic acid)-5α-hydroxy-7aβ-methylhexahydro-1-indanone-δ-lactone (HIL) in 1 ml 0.5M NaOH, and AD (50 mg/ml in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)) were used. Cultures (50 ml) were inoculated (1∶100) using pre-cultures grown in MM-Ac. Growth was followed by regular turbidity measurements (OD600nm). Turbidity measurements of AD grown cultures could not be accurately determined due to high background of the AD suspension. Protein content of the culture was therefore used as a measure for biomass formation and was determined as follows. A sample (0.5 ml) of the culture was pelleted by centrifugation (5 min 12,000 x g), thoroughly resuspended in 0.1 ml 1 M NaOH and boiled for 10 min. Then, 0.9 ml distilled water was added and the suspension was vortexed. An aliquot of 100 µl was mixed with 300 µl of distilled water and 100 µl of protein assay reagent (BioRad). Protein content of the sample was determined using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard as described by the manufacturer. For growth on solid media Bacto-agar (15 g/l; BD) was added. 5-Fluorocytosine stock solution (10 mg/ml) was prepared in distilled water, dissolved by heating to 50°C, filter-sterilized and added to autoclaved media.

Cloning, PCR and genomic DNA isolation

Escherichia coli DH5α was used as host for all cloning procedures. Restriction enzymes were obtained from Fermentas GmbH. Chromosomal DNA of cell cultures was isolated using the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. PCR was performed in a reaction mixture (25 µl) consisting of Tris-HCl (10 mM, pH 8), 1x standard polymerase buffer, dNTPs (0.2 mM), DMSO (2%), PCR primers (10 ng/µl each) and High-Fidelity DNA polymerase enzyme (Fermentas) or Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Applied Science). For colony PCR, cell material was mixed with 100 µl of chloroform and 100 µl of 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, vortexed vigorously and centrifuged (2 min, 14,000 x g). A sample of the upper aqueous phase (1 µl) was subsequently used as template for PCR. A standard PCR included a 5 min 95°C DNA melting step, followed by 30 cycles of 45 sec denaturing at 95°C, 45 sec annealing at 60°C and 1–3 min elongation at 72°C. The elongation time used depended on the length of the expected PCR amplicon, taking 1.5 min/1 kb as a general rule.

Electrotransformation of R. equi strains

Cells of R. equi strains were transformed by electroporation essentially as described [34]. Briefly, cell cultures were grown in 50 ml LB at 30°C until OD600 reached 0.8–1.0. The cells were pelleted (20 min at 4,500 x g) and washed twice with 10% ice-cold glycerol. Pelleted cells were re-suspended in 0.5–1 ml ice-cold 10% glycerol and divided into 200 µl aliquots.

MilliQ-eluted plasmid DNA (5–10 µl; GenElute Plasmid Miniprep Kit, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to 200 µl cells in 2 mm gapped cuvettes. Electroporation was performed with a single pulse of 12.5 kV/cm, 1000Ω and 25 µF. Electroporated cells were gently mixed with 1 ml LB medium (R. equi) and allowed to recover for 2 h at 37°C and 200 rpm. Aliquots (200 µl) of the recovered cells were plated onto selective agar medium. R. equi transformants were selected on LB agar containing apramycin (50 µg/ml) and appeared after 2–3 days of incubation at 30°C.

Construction of unmarked gene deletion mutants of Rhodococcus equi RE1

Unmarked gene deletion mutants of R. equi RE1 were constructed essentially as described previously [34]. All oligonucleotide primers used in the construction of plasmids necessary for the construction of the mutants are shown in Table S2. Plasmid pSelAct-ipd1, for the generation of an unmarked gene deletion of the ipdAB operon in R. equi RE1, was constructed as follows. The upstream (1,368 bp; primers ipdABequiUP-F and ipdABequiUP-R) and downstream (1,396 bp; primers ipdABequiDOWN-F and ipdABequiDOWN-R) flanking regions of the ipdAB genes were amplified by PCR. The obtained amplicons were ligated into EcoRV digested pBluescript(II)KS, rendering plasmids pEqui14 and pEqui16 for the upstream and downstream region, respectively. A 1.4 kb SpeI/EcoRV fragment of pEqui14 was ligated into SpeI/EcoRV digested pEqui16, generating pEqui18. A 2.9 kb EcoRI/HindIII fragment of pEqui18, harboring the ipdAB gene deletion and its flanking regions, was treated with Klenow fragment and ligated into SmaI digested pSelAct suicide vector [34]. The resulting plasmid was designated pSelAct-ipd1 for the construction of ipdAB gene deletion mutant R. equi ΔipdAB. Complementation of mutant strain RE1ΔipdAB was performed by introduction of a 4.4 kb DNA fragment obtained by PCR using primers ipdABequiContrUP-F and ipdABequiContrDOWN-R. The PCR product obtained was cloned into pSET152 and the resulting construct was introduced into RE1ΔipdAB by electroporation [34].

Mutant strain RE1ΔipdA2B2 was constructed by unmarked gene deletion of the ipdA2B2 operon from R. equi RE1 using plasmid pSelAct-ΔipdAB2. Double gene deletion mutant R. equi RE1ΔipdABΔipdA2B2 was made in R. equi RE1ΔipdAB mutant strain. Plasmid pSelAct-ΔipdAB2 was constructed as follows. The upstream (1,444 bp; primers ipdAB2equiUP-F and ipdAB2equiUP-R) and downstream (1,387 bp; ipdAB2equiDOWN-F, ipdAB2equiDOWN-R) regions of ipdAB2 were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA as template (Table S2). The amplicons were ligated into SmaI digested pSelAct, resulting in plasmids pSelAct-ipdAB2equiUP and pSelAct-ipdAB2equiDOWN, respectively. Following digestion with BglII/SpeI of both plasmids, a 1,381 bp fragment of pSelAct-ipdAB2equiDOWN was ligated into pSelAct-ipdAB2equiUP, resulting in pSelAct-ΔipdAB2 used for the construction of a ΔipdA2B2 gene deletion.

Plasmid pSelAct-fadE30 for the generation of an unmarked gene deletion of fadE30 in R. equi RE1 was constructed as follows. The upstream (1,511 bp; primers fadE30equiUP-F and fadE30equiUP-R) and downstream (1,449 bp; primers fadE30equiDOWN-F and fadE30equiDOWN-R) flanking genomic regions of fadE30 were amplified by a standard PCR using High Fidelity DNA polymerase (Fermentas GmbH). The obtained amplicons were ligated into the pGEM-T cloning vector (Promega Benelux), rendering pGEMT-fadE30UP and pGEMT-fadE30DOWN. A 1.4 kb BcuI/BglII DNA fragment was cut out of pGEMT-fadE30DOWN and ligated into BcuI/BglII linearized pGEMT-fadE30UP, resulting in pGEMT-fadE30. To construct pSelAct-fadE30, pGEMT-fadE30 was digested with NcoI and BcuI and treated with Klenow fragment. A 2.9 kb blunt-end DNA fragment, carrying the fadE30 gene deletion, was ligated into SmaI digested pSelAct [34]. The resulting plasmid was designated pSelAct-fadE30 and used for the construction of mutant strain R. equi RE1ΔfadE30. Complementation of mutant strain RE1ΔfadE30 was performed by the introduction of a 2.8 kb DNA fragment obtained by PCR using primers fadE30equiUP-F and fadE30Contr-R (Table S2). The PCR product obtained was cloned into EcoRV digested pSET152 and the resulting construct was introduced into RE1ΔfadE30 by electroporation [34].

Plasmid pSelAct-fadA6 for the generation of an unmarked gene deletion of fadA6 in R. equi RE1 was constructed as follows. The upstream (1,429 bp; primers fadA6equiUP-F and fadA6equiUP-R) and downstream (1,311 bp; primers fadA6equiDOWN-F and fadA6equiDOWN-R) flanking genomic regions of fadA6 were amplified by a standard PCR using High Fidelity DNA polymerase (Fermentas GmbH). The obtained amplicons were ligated into the pGEM-T cloning vector (Promega Benelux), rendering pGEMT-fadA6UP and pGEMT-fadA6DOWN. A 1.4 kb SpeI/BglII DNA fragment was cut out of pGEMT-fadA6UP and ligated into SpeI/BglII linearized pGEMT-fadA6DOWN, resulting in pGEMT-fadA6. To construct pSelAct-fadA6, pGEMT-fadA6 was digested with EcoRI and a 2.7 kb DNA fragment, carrying the fadA6 gene deletion, was ligated into EcoRI digested pSelAct [34]. The resulting plasmid was designated pSelAct-fadA6 and used for the construction of mutant strain R. equi RE1ΔfadA6.

GC analysis of HIP and 5OH-HIP formation in whole-cell biotransformations of AD

Strains were pre-grown (30°C, 200 rpm) in LB medium (10 ml) overnight and subsequently inoculated (1∶100) in 50 ml MM-Ac and incubated (30°C, 200 rpm) for 36 hours. AD (0.5 ml of 50 mg/ml stock in DMSO) was then added. Samples (0.25 ml) for GC analysis were collected and acidified with 5 µl 10% H2SO4 at several intervals. Progesterone (10 µl of a 5 mg/ml stock in ethylacetate) was added as an internal standard and samples were subsequently extracted using ethylacetate (1 ml). GC analysis was performed on a GC8000 TOP (Thermoquest Italia, Milan, Italy) equipped with an EC-5 column measuring 30 m by 0.25 mm (inner diameter) and a 0.25 µm film (Alltech, Ill., USA.) and FID detection at 300°C. Chromatographs obtained were analysed using Chromquest V 2.53 software (Thermoquest). HIP (200 mg/L) and 5OH-HIP (50 mg/L), supplied by MSD Oss, The Netherlands, were used as authentic samples.

Macrophage infection assays

The human monocyte cell line U937 [66] was grown in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) + NaHCO3 (1 g/L) + sodium pyruvate (0.11 g/L) + glucose medium (4.5 g/L) (RPMI 1640 medium), buffered with 10 mM HEPES (Hopax fine chemicals, Taiwan) and supplemented with penicillin (200 IU/ml), streptomycin (200 IU/ml) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were grown in suspension at 37°C and 5% CO2. For the macrophage survival assay, monocytes were grown for several days as described above. The culture medium was replaced with fresh culture medium and the cells were activated overnight with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (60 ng/ml, PMA, Sigma-Aldrich) to induce their differentiation to macrophages. The differentiated cells were spun down (5 min at 200 x g) and the pellet was re-suspended in fresh, antibiotic free RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS. For each strain to be tested, a tube containing 10 ml of a cell suspension (approximately 106 cells/ml) was inoculated with R. equi, pre-grown in nutrient broth (Difco, Detroit, MI., USA) at 37°C, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 10 bacteria per macrophage. The bacteria were incubated with the macrophages for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. The medium was replaced with 10 ml RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 µg/ml gentamycin and incubated again for 1 h to kill any extra-cellular bacteria. In assays with complemented mutant strains of RE1ΔipdAB and RE1ΔfadE30 ampicillin (100 µg/ml) was added in addition to gentamycin (100 µg/ml), since the apramycin cassette conferred gentamycin resistance. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for ampicillin was determined at 1.5–2 µg/ml ampicillin for wild type and all mutant and complemented mutant strains using an ampicillin Etest strip (AB Biodisk/bioMérieux, Solna, Sweden). The macrophages (with internalized R. equi) were spun down (5 min at 200 x g) and the pellet was re-suspended in 40 ml RPMI1640 medium, buffered with 10 mM HEPES and supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 µg/ml gentamycin, plus 10 µg/ml ampicillin in assays with the complemented mutant strains. This suspension was divided over four culture bottles (10 ml each) and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 4, 28, 52 and 76 h the macrophages (one culture bottle per strain per time point) were spun down (5 min at 200 x g) and the pellet washed twice in 1 ml antibiotic free RPMI1640 medium. Finally the pellet was lysed with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.01M phosphate buffered saline, followed by live count determination (plate counting).

Intratracheal challenge of foals with R. equi RE1ΔipdAB

Six 3 to 5-week-old foals were allotted with mare to two groups of three foals, ensuring an even distribution of age over the groups. At T = 0 all foals were challenged with 100 ml suspension of RE1ΔipdAB or R. equi RE1 (control) by trans-tracheal injection. Bacterial suspensions of R. equi strains RE1 or RE1ΔipdAB were made by plating onto blood agar (Biotrading Benelux, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands) and incubation for 24 h at 37°C. Bacteria were then harvested with 4 ml of sterile isotonic PBS per plate and diluted with sterile isotonic PBS to a final concentration of approximately 5×104 CFU/ml. Live count determination by plate counting was performed post-challenge. Infectivity titers were determined at 4.3×104 CFU/ml for RE1 and 7.1×104 CFU/ml for RE1ΔipdAB. Foals were examined daily post-challenge until necropsy for clinical signs using a numerical clinical scoring system with 13 parameters (Table S3). The clinical score was calculated as the sum of clinical scores of the 13 different parameters. At day 21 post-challenge a post-mortem examination was performed. The foals were euthanized by anaesthesia with xylazine (100 mg/100 kg) and ketamine (500 mg/100 kg) and subsequent bleeding to death. The lungs were weighed in order to calculate the lung to body weight ratio. Details of these examinations are described below for the immunization experiment.

Oral immunization of foals and subsequent challenge with virulent strain R. equi 85F

Oral immunization of foals was based on a study done by Hooper McGrevy et al. (2005) [53] with modifications. Eight 2 to 4-week-old foals were allotted to two groups of four foals each, ensuring an even distribution of age over the groups. During the experiment the foals suckled and the mares were fed according to standard procedures. R. equi strain RE1ΔipdAB was administered orally (1 ml) to the foals for vaccination at T = 0 and a booster at T = 14 days. The infectivity titer of RE1ΔipdAB was determined by plate counting (8.7×107 CFU/ml and 4.1×107 CFU/ml for the first and second vaccination, respectively). R. equi strain 85F (CNCM I-3250; [52], [64]) was used as challenge strain and plated onto blood agar and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Bacteria were harvested with 4 ml of sterile isotonic PBS per plate and diluted with sterile isotonic PBS to a final concentration of approximately 5×104 CFU/ml. At T = 28 days all foals were challenged with 100 ml R. equi 85F by trans-tracheal injection. Live count determination by plate counting was performed post-challenge in order to confirm the infectivity titer. Foals were examined daily for clinical signs using the numerical clinical scoring system described above (Table S3). Foals were weighed and blood was sampled at day of vaccination, day of challenge and at day of necropsy. Serum antibody titers against R. equi were determined as follows. R. equi strain 85F cell wall extract was prepared by resuspension of cells in 2% Triton X-114. The detergent phase containing VapA and other surface molecules (13.5 mg protein/ml) was diluted 2000x in 40 mM PBS and coated to microtiter plates during 16 h at 37°C. After washing with 40 mM PBS + 0.05% Tween, serial dilutions of test sera were made in the wells. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C and subsequent washing, the bound antibodies were quantified using HRP-rec protein G conjugate and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) as substrate. The antibody titers in sera were calculated using a positive standard serum with a defined titer of 9 (log2) as reference. Rectal swabs for bacterial re-isolation were sampled just before each vaccination and on frequent days after vaccination. The swab samples were serially diluted in physiological salt solution and plated on blood agar and incubated at 37°C for 16–24 h. R. equi colonies were initially identified by the typical non-hemolytic mucoid colony morphology, enumerated and expressed as CFU/ml.

At day 14 (controls; T = 42 days) or day 17–20 (vaccinates; T = 45–48 days) post-challenge foals were euthanized. The lungs were weighed in order to calculate the lung to body weight ratio. A complete post-mortem examination was performed with special attention to the lungs and gut with associated lymph nodes. Tissue samples (1 cm3) were excised from seven standard sites representative of the lobes of each half of the lung (3 sites per half and the accessory lobe); diseased tissue was preferentially selected for each site. The mirror image samples (the two samples of the equivalent lobe on each half) were pooled to give three samples per foal and a sample of the accessory lobe. Each (pooled) sample was homogenized, serially diluted and inoculated on blood agar plates and then incubated at 37°C for 16–24 h. R. equi colonies were enumerated and expressed as CFU/ml homogenate.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations of the “Dutch Experiments on Animal Act”. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Intervet International bv (Permit Number: REV 07060).

Statistical analysis

The R. equi counts (log10 CFU/ml) after incubation with macrophages for 4, 28, 52 and 76 h, reflecting the survival rate, were statistically analysed by ANOVA using a linear mixed model for repeated measurements and including time zero counts as covariate in the model Verbeke and Molenberghs [67]. Advanced statistical methods were applied for the ordinal scores over time of the daily clinical score using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE with p-values based on empirical standard error) and ANOVA for repeated measurements for continuous outcomes of rectal temperature, lung scores (% consolidation) and the quantitative re-isolation of R. equi from the different lung lobes. In these methods the correlation of the repeated measurements on subjects (i.e. animals) is taken into account. Statistical methods were conducted in SAS V9.1 (SAS Institute Cary, NC, USA) using two-sided tests and a significance level (α) of 0.05.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. PrescottJF 1991 Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 4 20 34

2. MosserDMHondalusMK 1996 Rhodococcus equi: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Trends Microbiol 4 29 33

3. YamshchikovAVSchuetzALyonGM 2010 Rhodococcus equi infection. Lancet Infect Dis 10 350 359

4. HondalusMKMosserDM 1994 Survival and replication of Rhodococcus equi in macrophages. Infect Immun 62 4167 4175

5. HondalusMK 1997 Pathogenesis and virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Vet Microbiol 56 257 268

6. MeijerWGPrescottJF 2004 Rhodococcus equi. Vet Res 35 383 396

7. von BargenKHaasA 2009 Molecular and infection biology of the horse pathogen Rhodococcus equi. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33 870 891

8. GiguèreSPrescottJF 1997 Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet Microbiol 56 313 334

9. TakaiSSekizakiTOzawaTSugawaraTWatanabeY 1991 Association between a large plasmid and 15 - to 17-kilodalton antigens in virulent Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun 59 4056 4060

10. TakaiSHinesSASekizakiTNicholsonVMAlperinDA 2000 DNA sequence and comparison of virulence plasmids from Rhodococcus equi ATCC33701 and 103. Infect Immun 68 6840 6847

11. GiguereSHondalusMKYagerJADarrahPMosserDM 1999 Role of the 85-kilobase plasmid and plasmid-encoded virulence-associated protein A in intracellular survival and virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun 67 3548 3557

12. JainSBloomBRHondalusMK 2003 Deletion of vapA encoding Virulence Associated Protein A attenuates the intracellular actinomycete Rhodococcus equi. Mol Microbiol 50 115 128

13. LetekMOcampo-SosaAASandersMFogartyUBuckleyT 2008 Evolution of the Rhodococcus equi vap pathogenicity island seen through comparison of host-associated vapA and vapB virulence plasmids. J Bacteriol 190 5797 5805

14. Tkachuk-SaadOPrescottJF 1991 Rhodococcus equi plasmids: isolation and partial characterization. J Clin Microbiol 29 2696 2700

15. MajnoGJorisI 1995 Apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis. An overview of cell death. Am J Pathol 146 3 15

16. LührmannAMauderNSydorTFernandez-MoraESchulze-LuehrmannJ 2004 Necrotic death of Rhodococcus equi-infected macrophages is regulated by virulence-associated plasmids. Infect Immun 72 853 862

17. von BargenKPolidoriMBeckenUHuthGPrescottJF 2009 Rhodococcus equi virulence-associated protein A is required for diversion of phagosome biogenesis but not for cytotoxicity. Infect Immun 77 5676 5681

18. CoulsonGBAgarwalSHondalusMK 2010 Characterization of the role of the pathogenicity island and vapG in the virulence of the intracellular actinomycete pathogen Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun 78 3323 3334

19. OliveiraAFFerrazLCBrocchiMRoque-BarreiraMC 2007 Oral administration of a live attenuated Salmonella vaccine strain expressing the VapA protein induces protection against infection by Rhodococcus equi. Microbes Infect 9 382 390

20. OliveiraAFRuasLPCardosoSASoaresSGRoque-BarreiraMC 2010 Vaccination of mice with salmonella expressing VapA: mucosal and systemic Th1 responses provide protection against Rhodococcus equi infection. PLoS One 5 e8644

21. HaghighiHRPrescottJF 2005 Assessment in mice of vapA-DNA vaccination against Rhodococcus equi infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 104 215 225

22. PhumoonnaTBartonMDVanniasinkamTHeuzenroederMW 2008 Chimeric vapA/groEL2 DNA vaccines enhance clearance of Rhodococcus equi in aerosol challenged C3H/He mice. Vaccine 26 2457 2465

23. AshourJHondalusMK 2003 Phenotypic mutants of the intracellular actinomycete Rhodococcus equi created by in vivo Himar1 transposon mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 185 2644 2652

24. LopezAMTownsendHGAllenALHondalusMK 2008 Safety and immunogenicity of a live-attenuated auxotrophic candidate vaccine against the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. Vaccine 26 998 1009

25. NavasJGonzález-ZornBLadrónNGarridoPVázquez-BolandJA 2001 Identification and mutagenesis by allelic exchange of choE, encoding a cholesterol oxidase from the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. J Bacteriol 183 4796 4805

26. PeiYDupontCSydorTHaasAPrescottJF 2006 Cholesterol oxidase (ChoE) is not important in the virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Vet Microbiol 118 240 246

27. PeiYNicholsonVWoodsKPrescottJF 2007 Immunization by intrabronchial administration to 1-week-old foals of an unmarked double gene disruption strain of Rhodococcus equi strain 103+. Vet Microbiol 125 100 110

28. WallDMDuffyPSDupontCPrescottJFMeijerWG 2005 Isocitrate lyase activity is required for virulence of the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun 73 6736 6741

29. PeiYParreiraVNicholsonVMPrescottJF 2007 Mutation and virulence assessment of chromosomal genes of Rhodococcus equi 103. Can J Vet Res 71 1 7

30. HeHZahrtTC 2005 Identification and characterization of a regulatory sequence recognized by Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence regulator MprA. J Bacteriol 187 202 212

31. MacArthurIParreiraVRLeppDMuthariaLMVazquez-BolandJA 2011 The sensor kinase MprB is required for Rhodococcus equi virulence. Vet Microbiol In press

32. AhmadSRoyPKBasuSKJohriBN 1993 Cholesterol side-chain cleavage by immobilized cells of Rhodococcus equi DSM89-133. Indian J Exp Biol 31 319 322

33. MurohisaTIidaM 1993 Some new intermediates in microbial side chain degradation of β-sitosterol. J Ferment Bioeng 76 174 177

34. Van der GeizeRde JongWHesselsGIGrommenAWJacobsAA 2008 A novel method to generate unmarked gene deletions in the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi using 5-fluorocytosine conditional lethality. Nucleic Acids Res 36 e151

35. LeeSSSihCJ 1967 Mechanisms of steroid oxidation by microorganisms. XII. Metabolism of hexahydroindanpropionic acid derivatives. Biochemistry 6 1395 1403

36. Van der GeizeRYamKHeuserTWilbrinkMHHaraH 2007 A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 1947 1952

37. PandeyAKSassettiCM 2008 Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105 4376 4380

38. YamKCD′AngeloIKalscheuerRZhuHWangJX 2009 Studies of a ring-cleaving dioxygenase illuminate the role of cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000344

39. HuYvan der GeizeRBesraGSGurchaSSLiuA 2010 3-Ketosteroid 9alpha-hydroxylase is an essential factor in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 75 107 121

40. MohnWWvan der GeizeRStewartGROkamotoSLiuJ 2008 The actinobacterial mce4 locus encodes a steroid transporter. J Biol Chem 283 35368 35374

41. RengarajanJBloomBRRubinEJ 2005 Genome-wide requirements for Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation and survival in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102 8327 8332

42. LetekMGonzálezPMacarthurIRodríguezHFreemanTC 2010 The genome of a pathogenic Rhodococcus: cooptive virulence underpinned by key gene acquisitions. PLoS Genet 6 e1001145

43. FinnRDMistryJTateJCoggillPHegerA 2010 The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res Database Issue 38 D211 222

44. HorinouchiMYamamotoTTaguchiKAraiHKudoT 2001 Meta-cleavage enzyme tesB is necessary for testosterone degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441. Microbiology (UK) 147 3367 3375

45. HorinouchiMHayashiTKoshinoHKuritaTKudoT 2005 Identification of 9,17-dioxo-1,2,3,4,10,19-hexanorandrostan-5-oic acid, 4-hydroxy-2-oxohexanoic acid, and 2-hydroxyhexa-2,4-dienoic acid and related enzymes involved in testosterone degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441. Appl Environ Microbiol 71 5275 5281

46. MicloAGermainP 1990 Catabolism of methylperhydroindanedione propionate by Rhodococcus equi: evidence of a MEPHIP-reductase activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 32 594 599

47. MicloAGermainP 1992 Hexahydroindanone derivatives of steroids formed by a Rhodococcus equi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 36 456 460

48. Van der GeizeRHesselsGIvan GerwenRvan der MeijdenPDijkhuizenL 2002 Molecular and functional characterization of kshA and kshB, encoding two components of 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase, a class IA monooxygenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis strain SQ1. Mol Microbiol 45 1007 1018

49. LoriaRM 2009 Beta-androstenes and resistance to viral and bacterial infections. Neuroimmunomodulation 16 88 95

50. KendallSLBurgessPBalhanaRWithersMTen BokumA 2010 Cholesterol utilization in mycobacteria is controlled by two TetR-type transcriptional regulators: kstR and kstR2. Microbiology 156 1362 1371

51. Chirino-TrejoJMPrescottJF 1987 Antibody response of horses to Rhodococcus equi antigens. Can J Vet Res 51 301 305

52. TakaiSShodaMSasakiYTsubakiSFortierG 1999 Restriction fragment length polymorphisms of virulence plasmids in Rhodococcus equi. J Clin Microbiol. 37 3417 3420

53. Hooper-McGrevyKEWilkieBNPrescottJF 2005 Virulence-associated protein-specific serum immunoglobulin G-isotype expression in young foals protected against Rhodococcus equi pneumonia by oral immunization with virulent R. equi. Vaccine 23 5760 5767

54. MartensRJMartensJGFiskeRAHietalaSK 1989 Rhodococcus equi foal pneumonia: protective effects of immune plasma in experimentally infected foals. Equine Vet J 21 249 255

55. MadiganJEHietalaSMullerN 1991 Protection against naturally acquired Rhodococcus equi pneumonia in foals by administration of hyperimmune plasma. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 44 571 578

56. HinesSAKanalySTByrneBAPalmerGH 1997 Immunity to Rhodococcus equi. Vet Microbiol 56 177 185

57. HurleyJRBeggAP 1995 Failure of hyperimmune plasma to prevent pneumonia caused by Rhodococcus equi in foals. Aust Vet J 72 418 420

58. GiguèreSGaskinJMMillerCBowmanJL 2002 Evaluation of a commercially available hyperimmune plasma product for prevention of naturally acquired pneumonia caused by Rhodococcus equi in foals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 220 59 63

59. DawsonTRHorohovDWMeijerWGMuscatelloG 2010 Current understanding of the equine immune response to Rhodococcus equi. An immunological review of R. equi pneumonia. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 135 1 11

60. WeinstockDMBrownAE 2002 Rhodococcus equi: an emerging pathogen. Clin Infect Dis 34 1379 1385

61. RodaRHYoungMTimponeJRosenJ 2009 Rhodococcus equi pulmonary-central nervous system syndrome: brain abscess in a patient on high-dose steroids—a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 63 96 99

62. KedlayaIIngMBWongSS 2001 Rhodococcus equi infections in immunocompetent hosts: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 32 e39 e46

63. De la Pena-MoctezumaAPrescottJF 1995 Association with HeLa cells by Rhodococcus equi with and without the virulence plasmid. Vet Microbiol 46 383 392

64. BenoitSBenachourATaoujiSAuffrayYHartkeA 2001 Induction of vap genes encoded by the virulence plasmid of Rhodococcus equi during acid tolerance response. Res Microbiol 152 439 449

65. VishniacWSanterM 1957 The thiobacilli. Bacteriol Rev 21 195 213

66. SundstromCNilssonK 1976 Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U937). Int J Cancer 17 565 577

67. VerbekeGMolenberghsG 2000 Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York Springer-Verlag

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Crystal Structure of Reovirus Attachment Protein σ1 in Complex with Sialylated OligosaccharidesČlánek A Protein Thermometer Controls Temperature-Dependent Transcription of Flagellar Motility Genes inČlánek Modulation of NKp30- and NKp46-Mediated Natural Killer Cell Responses by Poxviral Hemagglutinin

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 8- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Phenotypic Screens, Chemical Genomics, and Antimalarial Lead Discovery

- Characterisation of Regulatory T Cells in Nasal Associated Lymphoid Tissue in Children: Relationships with Pneumococcal Colonization

- Crystal Structure of Reovirus Attachment Protein σ1 in Complex with Sialylated Oligosaccharides

- Absence of Cross-Presenting Cells in the Salivary Gland and Viral Immune Evasion Confine Cytomegalovirus Immune Control to Effector CD4 T Cells

- Transcriptomic Analysis of Host Immune and Cell Death Responses Associated with the Influenza A Virus PB1-F2 Protein

- A Quorum Sensing Regulated Small Volatile Molecule Reduces Acute Virulence and Promotes Chronic Infection Phenotypes

- Autocrine Regulation of Pulmonary Inflammation by Effector T-Cell Derived IL-10 during Infection with Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- A Protein Thermometer Controls Temperature-Dependent Transcription of Flagellar Motility Genes in

- Association of Human TLR1 and TLR6 Deficiency with Altered Immune Responses to BCG Vaccination in South African Infants

- Histo-Blood Group Antigens Act as Attachment Factors of Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Infection in a Virus Strain-Dependent Manner

- MrkH, a Novel c-di-GMP-Dependent Transcriptional Activator, Controls Biofilm Formation by Regulating Type 3 Fimbriae Expression

- Beta-HPV 5 and 8 E6 Promote p300 Degradation by Blocking AKT/p300 Association

- Modulation of NKp30- and NKp46-Mediated Natural Killer Cell Responses by Poxviral Hemagglutinin

- Transportin 3 Promotes a Nuclear Maturation Step Required for Efficient HIV-1 Integration

- Coordination of KSHV Latent and Lytic Gene Control by CTCF-Cohesin Mediated Chromosome Conformation

- A Novel Persistence Associated EBV miRNA Expression Profile Is Disrupted in Neoplasia

- The Plant Pathogen pv. Is Genetically Monomorphic and under Strong Selection to Evade Tomato Immunity

- IL-10 Blocks the Development of Resistance to Re-Infection with

- Anti-Apoptotic Machinery Protects the Necrotrophic Fungus from Host-Induced Apoptotic-Like Cell Death during Plant Infection

- Crystal Structure of PrgI-SipD: Insight into a Secretion Competent State of the Type Three Secretion System Needle Tip and its Interaction with Host Ligands

- Evades Immune Recognition of Flagellin in Both Mammals and Plants

- Tumor Cell Marker PVRL4 (Nectin 4) Is an Epithelial Cell Receptor for Measles Virus

- Provides Insights into the Evolution of the Salmonellae

- B Cell Repertoire Analysis Identifies New Antigenic Domains on Glycoprotein B of Human Cytomegalovirus which Are Target of Neutralizing Antibodies

- Thy1 Nk Cells from Vaccinia Virus-Primed Mice Confer Protection against Vaccinia Virus Challenge in the Absence of Adaptive Lymphocytes

- The Cytokine Network of Acute HIV Infection: A Promising Target for Vaccines and Therapy to Reduce Viral Set-Point?

- Dendritic Cell Status Modulates the Outcome of HIV-Related B Cell Disease Progression

- Differential Contribution of PB1-F2 to the Virulence of Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza A Virus in Mammalian and Avian Species

- A Communal Bacterial Adhesin Anchors Biofilm and Bystander Cells to Surfaces

- Two Group A Streptococcal Peptide Pheromones Act through Opposing Rgg Regulators to Control Biofilm Development

- Activation of HIV Transcription by the Viral Tat Protein Requires a Demethylation Step Mediated by Lysine-specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1/KDM1)

- Unique Evolution of the UPR Pathway with a Novel bZIP Transcription Factor, Hxl1, for Controlling Pathogenicity of

- Disruption of PML Nuclear Bodies Is Mediated by ORF61 SUMO-Interacting Motifs and Required for Varicella-Zoster Virus Pathogenesis in Skin

- Flagellar Motility Is Not Directly Required to Maintain Attachment to Surfaces

- Viral Infection Induces Expression of Novel Phased MicroRNAs from Conserved Cellular MicroRNA Precursors

- Functional Cure of SIVagm Infection in Rhesus Macaques Results in Complete Recovery of CD4 T Cells and Is Reverted by CD8 Cell Depletion

- Recruitment of the Major Vault Protein by InlK: A Strategy to Avoid Autophagy

- The Steroid Catabolic Pathway of the Intracellular Pathogen Is Important for Pathogenesis and a Target for Vaccine Development

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Tumor Cell Marker PVRL4 (Nectin 4) Is an Epithelial Cell Receptor for Measles Virus

- Two Group A Streptococcal Peptide Pheromones Act through Opposing Rgg Regulators to Control Biofilm Development

- Differential Contribution of PB1-F2 to the Virulence of Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza A Virus in Mammalian and Avian Species

- Recruitment of the Major Vault Protein by InlK: A Strategy to Avoid Autophagy

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání