-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe CSN/COP9 Signalosome Regulates Synaptonemal Complex Assembly during Meiotic Prophase I of

Meiosis is a cellular division required for the formation of gametes, and therefore sexual reproduction. Accurate chromosome segregation is dependent on the formation of crossovers, the exchange of DNA between homologous chromosomes. A key process in the formation of crossovers is the assembly of the synaptonemal complex (SC) between homologs during prophase I. How functional SC structure forms is still not well understood. Here we identify CSN/COP9 signalosome complex as having a clear role in chromosome synapsis. In CSN/COP9 mutants, SC proteins aggregate and fail to properly assemble on homologous chromosomes. This leads to defects in homolog pairing, repair of meiotic DNA damage and crossover formation. The data in this paper suggest that the role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome is to prevent the aggregation of central region proteins during SC assembly.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004757

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004757Summary

Meiosis is a cellular division required for the formation of gametes, and therefore sexual reproduction. Accurate chromosome segregation is dependent on the formation of crossovers, the exchange of DNA between homologous chromosomes. A key process in the formation of crossovers is the assembly of the synaptonemal complex (SC) between homologs during prophase I. How functional SC structure forms is still not well understood. Here we identify CSN/COP9 signalosome complex as having a clear role in chromosome synapsis. In CSN/COP9 mutants, SC proteins aggregate and fail to properly assemble on homologous chromosomes. This leads to defects in homolog pairing, repair of meiotic DNA damage and crossover formation. The data in this paper suggest that the role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome is to prevent the aggregation of central region proteins during SC assembly.

Introduction

The formation of haploid gametes is critical for reproduction in most eukaryotic organisms. Meiosis is the specialized cellular division leading to the formation of gametes, which in metazoans are eggs and sperm. Unlike mitosis, meiosis has one round of chromosome replication followed by two divisions: the first division is referred to as MI, in which homologous chromosomes segregate from each other, and the second division is referred to as MII, where sister chromatids segregate. It is essential that chromosome segregation during the divisions occurs correctly or an aberrant number of chromosomes will be present in the gametes, resulting in aneuploid eggs or sperm and consequently aneuploid or inviable offspring [1].

In meiotic prophase I, preceding the first division, homologous chromosomes pair, synapse, and form crossovers to recombine the genetic material. Crossovers and sister chromatid cohesion result in chiasmata, the visually detectable connections between homologous chromosomes observed in late prophase I. Chiasmata allow homologs to align properly at the metaphase plate during meiosis I and subsequently segregate to opposite poles [2]. All prophase I steps are highly regulated, ensuring that meiotic prophase proceeds correctly.

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is an evolutionarily conserved protein structure connecting pairs of homologous chromosomes during most prophase I stages and is required for formation of most crossovers [3]. Absent or improperly formed SC inhibits crossover formation, resulting in missegregation of chromosomes [4]. The SC is composed of lateral element proteins, which bind to the chromosomal axis of each homolog. The lateral element proteins are connected by the central region (CR) proteins, forming a physical link which holds homologous chromosomes together throughout most of meiotic prophase I [5]–[8]. In C. elegans, lateral element proteins include HTP-1/2, HTP-3, and HIM-3 [5]–[10]; there are four known CR proteins: SYP-1, SYP-2, SYP-3, and SYP-4 (collectively known as SYPs). The SYPs act in an interdependent manner: if one is missing, the CR does not form. The phenotypic consequences of mutations in all four SYPs are indistinguishable: lack of synapsis and failure to form crossovers [11]–[13].

In certain mutants, CR proteins can also assemble into aberrant SC-like structures that are non-functional and do not support crossover formation. In C. elegans, CR components are found to assemble between non-homologous chromosomes (non-homologous synapsis [7], [9] or sisters [11], [14]). CR proteins can also self-aggregate, forming polycomplexes (PCs). By electron microscopy, PCs are reminiscent of SC structures and in most cases, they are not associated with DNA [15]. Although PCs can contain multiple SC proteins, single components of the CR can form PCs without the aid of lateral element proteins [16]. PCs can be found in wild-type meiotic cells, when the SC assembles or disassembles, but these are small structures that are tightly regulated [17]. In some aberrant situations, large and persistent PCs are observed, indicating that in the absence of proper regulation CR proteins have a natural propensity to aggregate. These structures are found in tissue culture cells where CRs are expressed ectopically [18] and frequently found in yeast meiotic mutants [19]. In C. elegans, there are four examples for large and persistent PC-like structures (upon SC assembly [14], [20], [21] or disassembly [22]). The molecular mechanism leading to PC formation in these mutants is unknown.

Pathways regulating SC assembly to prevent PCs may be different between yeast meiosis and meiosis in other organisms. When recombination or SC assembly is perturbed, the yeast CR protein Zip1 readily forms PCs. On the contrary, none of the C. elegans CR proteins/SYPs aggregate when some SC proteins are missing or recombination fails [11]–[13], [23] These observations raise the possibility that CR proteins self-aggregation (i.e., form PCs) is more tightly regulated in C. elegans meiosis.

In yeast and mouse, lateral element proteins have been shown to be post-translationally modified via sumoylation and phosphorylation which affects SC morphogenesis [24], [25]. Proper SC assembly may also involve post-translational modifications of CR proteins. In C. elegans, it is not known if such mechanisms exist and how CR proteins are post-translationally modified.

The CSN/COP9 signalosome is a highly conserved protein complex involved in post-translational modifications, originally described in Aradidopsis as a repressor of photomorphogenesis [26]. The complex is comprised of eight subunits which are similar to the lid complex of the 26S proteasome [27], [28]. Seven CSN/COP9 signalosome subunits have been identified in C. elegans. Five subunits (CSN-1,2,3,4, and 7) contain a PCI (proteasome, COP9 signalosome, initiation factor 3) domain and two (CSN-5 and CSN-6) contain MPN (Mpr1-Pad1-N-terminal) domains [28]. The PCI domains are thought to facilitate protein-protein interactions and may also have nucleic acid binding properties [29]. The CSN-5 MPN domain contains a JAMM (Jab1/MPN/Mov34) motif, which includes the metalloisopeptidase catalytic activity, which can cleave ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like post-translational modifiers (such as NED-8/Rub1) [30]–[33]. The CSN-6 MPN domain lacks the JAMM motif and thus the metalloisopeptidase activity [34], [35]. The signalosome is involved in the regulation of protein function via multiple pathways, but most studies have been carried out in the context of ubiquitin pathway via the CULLIN-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases (CRLs) [27], [32], [36]. The signalosome, through deneddylation of the CRLs, down-regulates proteasome degradation and/or monoubiquitination of substrates [36]–[38]. This deneddylation activity occurs in the context of the signalosome holocomplex. The CSN/COP9 signalosome affects cell cycle, gene expression, and DNA damage repair, through mechanisms that do not necessarily involve CRLs [39]–[41]. The understanding of the role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome in meiosis is limited. In Drosophila, the CSN/COP9 signalosome is required for meiotic progression [42]. A recent study in Arabidopsis identified a role for neddylation in crossover distribution and SC assembly, but the CSN/COP9 signalosome was not yet examined in this context [43].

Null mutants of the CSN/COP9 signalosome generated in other model organisms (yeast and Drosophila) have shown that the loss of one subunit renders it inactive and leads to lethality [44]–[47]. CSN-5 (also known as Jab1) has been shown to act outside the holocomplex in such cellular activities as nuclear export, degradation, and protein stabilization [48], [49]. The CSN-5 subunit of CSN/COP9 signalosome in C. elegans has also been implicated in muscle development [50], and the regulation of germline P-granule component, GLH-1, through interactions with KGB-1, a member of the JNK kinase family [51], [52]. While CSN-5 RNAi has been shown to reduce the size of gonads in C. elegans [51], [52], a role for CSN-5 in meiotic chromosome behavior has not been examined.

The work described here indicates a novel role for the CSN/COP9 signalosome in meiotic prophase I events that are key for the formation of functional gametes. Mutations in signalosome components specifically affected SC assembly and oocyte maturation. In csn mutants SYP-1 aggregated (PC-like structures) formed and persisted throughout meiotic prophase I. Additionally, we observed reduced chromosomal pairing throughout meiotic prophase as well as disruption in meiotic recombination and crossover formation. The defects in crossover formation were partially suppressed by reducing the levels of neddylation or ubiquitination. We also found an increase in apoptosis, likely due to the disruption of events earlier in pachytene. Oocyte maturation also was disrupted, leading to a severe reduction in the number of oocytes in diakinesis, which rendered the worms sterile. Our working model is that the CSN/COP9 complex regulates SC morphogenesis by inhibiting SYP DNA-independent self-assembly. Without CSN/COP9 function SC morphogenesis is perturbed (leading to CR aggregate formation) as are subsequent downstream events (e.g., pairing and recombination) which are dependent on proper SC formation. Furthermore, the CSN signalosome affects oocyte maturation and permitting meiotic progression via MAPK/MPK-1 activation.

Results

csn mutants exhibit defects in SC morphogenesis and meiotic progression

We identified csn-5 as a gene involved in SC morphogenesis via an RNAi suppressor/enhancer screen of a mutant (akir-1) exhibiting aberrant SC aggregation. Previous studies utilizing RNAi methodology to examine the role of the CSN complex genes in C. elegans demonstrated that csn-5 was required for normal gonad morphology. csn-5(RNAi) resulted in formation of short gonads and down-regulation of the P-granule component GLH-1 [51], [52]. However, SC morphogenesis, chromosome dynamics, or meiotic recombination in meiotic prophase I were not examined in these studies. Here we focused our studies on the function of the CSN/COP9 signalosome in these meiotic processes.

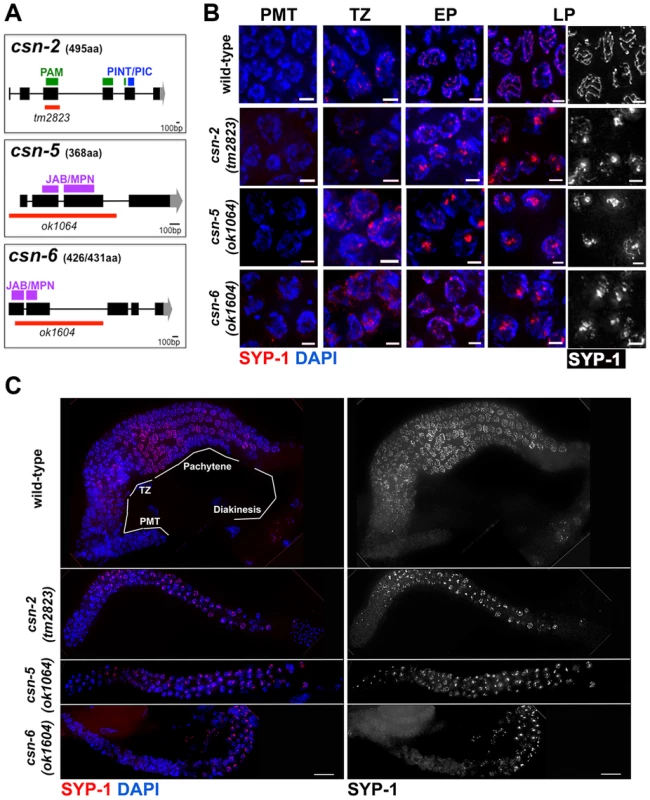

Three deletion alleles were analyzed in this study: csn-2(tm2823), csn-5(ok1064) and csn-6(ok1604) (See also Materials and Methods). The csn-2(tm2823) allele is missing most of exon 3 which results in deletion of 28% of the coding region, including the PAM sub-domain [53] in the PCI domain (Figure 1A). The csn-5(ok1064) allele is missing exons 1, 2, and 3 which results in deletion of 64% of the coding region (including the MPN catalytic domain, Figure 1A). The csn-6(ok1064) allele is missing most of exons 1 and all of exon 2 which results in deletion of 43% of the coding region (including most of the MPN domain, Figure 1A). The csn-2(tm2823), csn-5(ok1064) and csn-6(ok1604) alleles will be referred here collectively as csn mutants.

Fig. 1. SC central element assembly defects in csn mutants.

A) CSN alleles used in this study: black rectangles represent exons, black lines introns, gray areas represent UTR regions, red lines region deleted and purple, green and blue rectangles the protein domains. PAM and PINT are subdomains of the PCI domain, B) Micrographs of SYP-1 (red or grey scaled) and DAPI (blue) stained wild-type and csn-5 mutants nuclei representing the various stages of the C. elegans gonad. Images are projections through half of a three-dimensional data stacks. Scale bar is 2 µm. PMT = pre-meiotic tip, TZ = transition zone, EP = early pachytene, MP = mid pachytene, LP = late pachytene. SYP-1 aggregates appear in the TZ-like stage of the gonad and persist through the LP-like stage. C) Whole gonad from wild-type and csn mutants SYP-1 and DAPI stained. Images show smaller gonads in csn mutants and lack of oocytes progressing through diakinesis. Scale Bar 16 µm. SYP-1 (grayscale) staining only of gonads showing aggregation throughout the gonad, starting at transition zone. In wild-type nuclei, SC assembly is initiated at the transition zone (leptotene/zygotene) when SC proteins load on chromosomes (Figure 1B); the SC is fully assembled at pachytene. SC disassembly is initiated at the end of pachytene and CR disassembly is complete by the end of diakinesis. To determine if SC morphogenesis was affected in csn mutants, we performed immunohistochemical analyses using antibodies against SYP-1, SYP-4, HIM-3, and HTP-3 [5], [8], [12], [22] (Figure 1B,C; Figure S1 and S2). In all csn mutants, we observed smaller, morphologically different gonads compared to wild-type (Figure 1C), as previously published for csn-5(RNAi) [51], [52]. The nuclei in the csn mutant gonads were unevenly spaced throughout the gonad. There also appeared to be no distinct rachis (central canal) as in wild-type worms. The chromosomes of csn mutants clustered to one side of the nucleus (a polarized organization) as found in the wild-type transition zone (leptotene/zygotene) nuclei; this is indicative of meiotic entry [54]. Unlike wild-type, in the csn mutants these polarized nuclei were found throughout the gonad intermixed with nuclei with a dispersed chromosomal organization. The persistence of polarized chromosomes has been observed previously in synapsis defective mutants [11]. In addition to the persistent polarized chromosome organization, we also determined the mitotic/meiotic boundary using antibodies for lateral element proteins, HIM-3 and HTP-3. Since these lateral element proteins localize to chromosomes axes upon the transition from mitosis to meiosis. This localization occurred concurrently with polarization of chromosomal organization and did not show any defects in the germline of csn mutants. These data indicate: 1) the transition from mitosis to meiosis took place in the csn mutants, and 2) the localization of lateral element proteins of the SC was not perturbed in csn mutants (Figure S1). Thus, although gonads are smaller in csn mutants and have fewer nuclei, meiotic entry has occurred and SC assembly has initiated.

In contrast to the pattern of localization of lateral element proteins in the csn mutants, the CR protein SYP-1 showed an aberrant pattern of localization. SYP-1 protein aggregates (PC-like structures) were found in the transition-like zone at the distal end of the gonad and through the late-pachytene-like zone in the proximal end of the gonad. These occurred in 100% of the gonads examined (wild-type n = 26, csn-2 n = 37, csn-5 n = 34, csn-6 n = 35; p<0.0005; Fisher's Exact Test) for all csn mutants (Figure 1B). CR/SYP aggregates were 4 fold wider than a typical SC (width of wild-type SC - 0.22 µm±0.23, n = 25, width of SC aggregate - csn-2 0.83 µm±0.23, n = 70 and csn-5 0.86 µm ±0.31, n = 90 p≪0.001 Mann Whitney Test) and typically there was one aggregate per nucleus (csn-2 1.12, n = 62 and csn-5 1.13, n = 82). While some nuclei contained a single SYP-1 aggregate with no additional SYP localization, most nuclei contained partially assembled linear SC (similar to that observed in wild-type gonads) in addition to the aggregate (detailed analysis below). As there are currently four SYP proteins, we examined the localization of SYP-4 in csn-5 mutants as well as GFP::SYP-3 in csn-2 and csn-5 mutants to identify if the aggregation defects were specific to SYP-1 or generally affect all the CR components. SYP-3 and SYP-4 also form persistent aggregates suggesting the defects observed in the csn mutants are not specific to SYP-1 (Figure S2).

P-granules are germline RNA storage compartments that are composed of mRNAs and proteins; these include GLH-1 and PGL-1 proteins that are important for P-granule function. A recent paper by Bilgir et al., 2013 described failure in SC assembly in pgl-1 mutants. Since GLH-1 is known to be regulated by CSN-5 [55], SYP aggregation could be induced by a reduction in function of GLH-1 (and the consequent P-granule defects). CSN-5 promotes GLH-1 stabilization by competing with KGB-1 for binding to GLH-1 [51], [52]. If CSN-5 influenced SC through its role in P-granule function, than glh-1 mutants should show similar phenotypes (SC aggregation) to csn-5 mutants and kgb-1 should destabilize SC (lack of SC). We did not observe any changes in SC structure, or any aggregation, in kgb-1 and glh-1 mutants (Figure S3.) We conclude from this, that P-granule destabilization is likely not the cause of SYP aggregation in csn mutants.

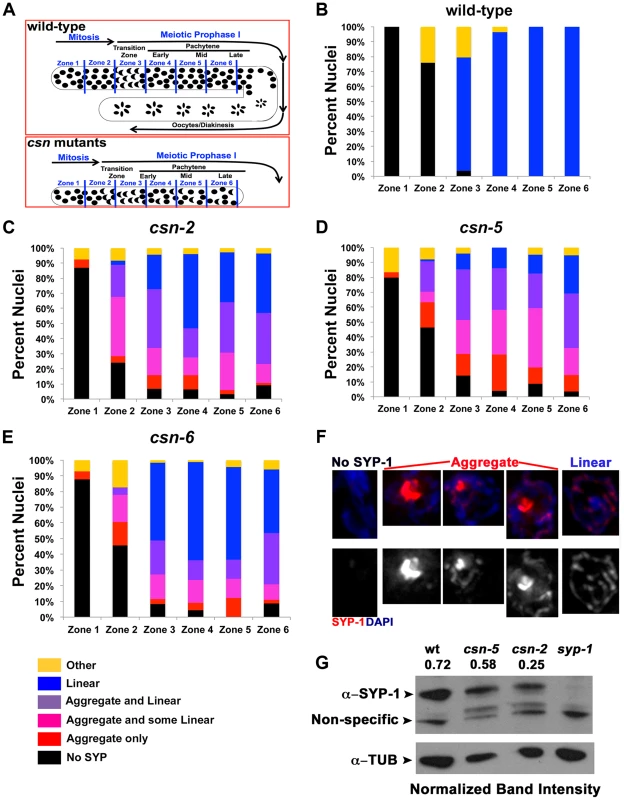

csn-2, csn-5 and csn-6 mutants affect CR assembly

Having determined all three csn mutants display SYP aggregation, we asked if the defects in SC assembly were indistinguishable in our mutants. Not all nuclei within the transition-like zone and pachytene-like zone had aggregates. The gonads were divided into six zones sized as in Colaiacovo 2003 ([4], Figure 2A) and were scored for the percent of nuclei with aggregates in each zone. Each zone represents a size unit (36 µM×36 µM window) organized sequentially (zone 1 being the distal pre-meiotic tips (PMT) and zone 6 the proximal late pachytene region). This division into zones was performed according to the standard protocol for quantitative analysis of early to mid-meiotic events in the C. elegans germline, (e.g., RAD-51 analysis, also see Materials and Methods). We divided the SYP-1 localization pattern to 6 categories and quantified the percent of nuclei in each category in each zone. Linear refers to SYP-1 that is morphologically similar to that observed in wild-type. Aggregated SYP was divided into three categories reflecting the amount of linear SYP-1 that is present in nuclei alongside with aggregate: linear (most of the DAPI had linear SYP-1), aggregate only (no linear SYP-1) and intermediate (some linear). csn-2 and csn-6 mutants showed a lower percent of nuclei with SYP-1 aggregates compared to csn-5 (Figure 2B–D percent nuclei with aggregates out of total number of nuclei; wild-type 0%, csn-2 41%, csn-5, 57%, csn-6 30%, for statistics and n values see figure legend). Analysis of SYP-1 localization in the csn-2; csn-5 double mutant revealed similar findings; however early meiotic nuclei tended to have low aggregation levels, comparable to csn-2, while later meiotic nuclei were more similar to csn-5 (Figure S4). Overall, the percent of aggregated nuclei varied between gonads (e.g., 50–72% for csn-5), but mutant gonads always contained SYP-1 aggregates and wild-type gonads never harbored SYP-1 aggregates. The early appearance of SYP aggregates as SC assembly initiates (zone 2–3) indicates that the primary defect observed in csn mutants is in SC assembly.

Fig. 2. Quantification of the SYP-1 aggregates.

A) Schematic representation of the zones of the C. elegans gonad. PMT = pre-meiotic tip, TZ = transition zone, EP = early pachytene, MP = mid pachytene, LP = late pachytene. B–E) Quantification of SYP-1 aggregates in zones of the gonad. Percent of nuclei with: no SYP-1 (black), linear SYP-1 (blue), aggregated SYP-1 (purple pink and red) and other (yellow), zones as in A, n nuclei scored wild type: 1123, csn-2: 868, csn-5: 1020, csn-6: 85, p<0.0005 for pairwise comparisons; Fisher's Exact Test F) Representative images of nuclei scored in C–D all taken from the same gonad in late pachytene of csn-2 mutants, G) Western Blot confirming the reduction of expression of SYP-1 in csn mutants. Normalization values (α-SYP-1/α-TUB) shown are the average of 2 different experiments. Normalized intensities: wild-type 0.72±0.26, csn-2 0.24±0.20 and csn-5 0.58±0.11. SYP-1 aggregation could result from over-expressing SYPs [12]. To address this point; we performed a Western blot analysis to determine the level of SYP-1 in the csn-2 and csn-5 mutants. Both csn mutants had a reduced level of SYP-1 compared to wild-type (Figure 2G, csn-2 40%±23 and csn-5 80%±5 of wild-type, average between experiments). We also performed a similar experiment using HTP-3 as a normalization control and found similar results (Figure S5 csn-2 76%±15 and csn-5 65%±6 of wild-type). We also utilized a cytology-based assay to quantify the amount of nuclear SYP-1 protein in csn nuclei compared to wild-type. In this analysis, the intensity of an image was used for calculating the amount of protein using standard methodologies (for details see Materials and Methods). We observed a decrease in nuclear SYP-1 in the csn-5 mutant, but not for csn-2, compared to wild-type (Figure S5). These data argue that the SYP-1 aggregates are not the result of detectable over-expression of SYP-1.

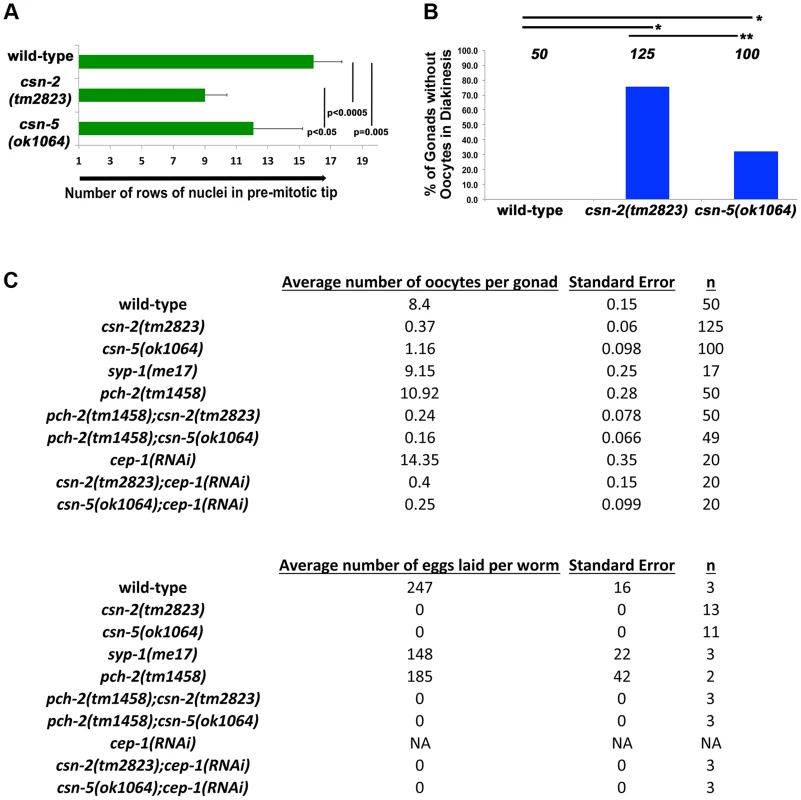

csn-2 and csn-5 are required for gonad proliferation and fertility

The overall length of the gonads of csn mutants is shorter than observed in wild-type (Table S4), which could result from reduced proliferation of mitotic cells. If mitotic proliferation (prior to meiotic entry) was affected, the size of the mitotic zone (i.e., the PMT) would be shorter in csn mutants. As nuclei enter meiosis, they acquire a polarized configuration of chromosomes indicating meiosis was initiated. We used this polarization to measure the length of the PMT of gonads for each genotype. Our analysis focused on csn-2 and csn-5, although csn-6 showed similar phenotypes that were not quantified in such detail. In the csn mutants, the PMT region was 60% and 77% of the length in the wild type (Figure 3A). Similar analysis using HTP-3 antibody as a marker for meiotic entry revealed similar findings: PMT region was ∼60% shorter than in wild-type for both mutants (for each strain p = 0.004 for wild-type vs. csn-2; p = 0.002 for wild-type vs. csn-5 and p = 0.83 for csn-2 vs csn-5; Mann Whitney Test) One interpretation of these data is that the transition from mitosis to meiosis occurs earlier in these mutants compared to wild-type.

Fig. 3. Quantification of the lack of oocytes and fecundity test.

A) Relative sizes of the pre-meiotic tips for wild-type and the csn mutants. The size of the mitotic zone is reduced in csn mutants. n = 10 for each strain p<0.0005 for wild-type vs. csn-2; p = 0.005 for wild-type vs. csn-5 and p<0.05 for csn-2 vs. csn-5; Mann Whitney Test B) Quantification of the number of gonads that contained oocytes in diakinesis for the csn mutants, *pMW<0.0005 and **pMW<0.005, Mann Whitney Test C) Top: the average number of oocytes in diakinesis for the csn mutants and the csn mutant, apoptosis checkpoint double mutants. Bottom: the average number of eggs laid for csn mutants and apoptosis checkpoint double mutants. csn mutants have a severe reduction in the number of oocytes and lay no eggs. When nuclei move to diakinesis, the final stage of meiotic prophase I, wild-type gonads contain an average of 8.1±1.1 diakinesis nuclei. These diakinesis nuclei are also referred to as oocytes [56], although the cellularization process occurs only towards the end of diakinesis. Unlike wild-type, most gonads of csn homozygotes lacked diakinesis nuclei/oocytes (Figure 3B). In csn-2 mutants, only about 25% of the gonads had diakinesis nuclei, and an average of 0.8±0.76 per gonad (Figure 3C). In csn-5 mutants, 65% of the gonads had diakinesis nuclei with an average of 1.23±0.98 per gonad. We performed an egg lay assay to determine the number of eggs laid and their viability. For the csn mutants, no eggs were laid in a three-day period; in contrast wild-type worms had an average of 247±16 eggs laid per worm (Figure 3C).

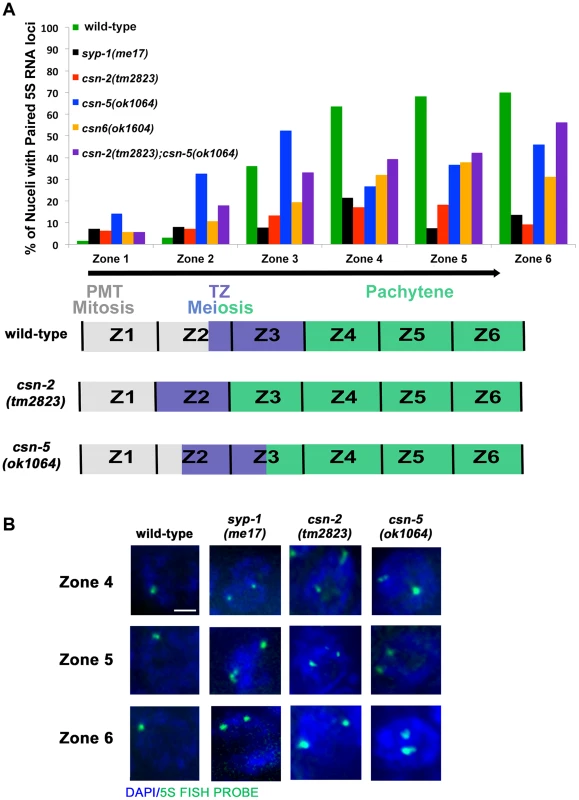

csn-2, csn-5 and csn-6 are required for pairing stabilization

Pairing interactions between homologous chromosomes are initiated in a SC-independent manner at specific chromosomal sites (pairing centers). The term pairing stabilization describes pairing interactions that spread outside the pairing centers and lead to the persistence of homolog association throughout pachytene. In syp mutants, loci distant from the pairing centers exhibit a very low level of pairing throughout meiosis [54]. Since the data indicated that csn mutants lack a fully functional SC; we expected to find that pairing stabilization had been compromised in the csn mutants, similar to syp mutants. To test this, we used a 5S ribosomal RNA locus on the center of chromosome V to analyze pairing interactions between homologous chromosomes by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The gonads were divided into six zones and were scored for the percent of nuclei with paired 5S loci in each zone ([57], Figure 4 and Tables S1 and S2 for n values and statistics).

Fig. 4. Pairing stabilization is affected in csn mutants.

A) Analysis of pairing stabilization between wild-type, syp-1(me17), csn mutants. A schematic representation of the timing of meiotic stages relative to the zones in the C elegans gonad. zone 1 = pre-meiotic tip, zone 2 and 3 = transition from mitosis to meiosis, zone 4–6 = pachytene. The black arrow represents the movement of nuclei through the stages (zones) of meiosis. csn mutants show defects in pairing stabilization number of nuclei counted and p-values can be found in Sup.Tables 1 and 2. B) High magnification micrographs of individual nuclei. Images are projections through three-dimensional data stacks. 5S FISH probe foci are in green and DAPI stained chromosomes are in blue. zone 4 = early pachytene, zone 5 = mid pachytene, zone 6 = late pachytene. Scale bar is 2 µm. In zone 1, as expected, wild-type and syp-1(me17) control nuclei, as well as the csn mutants, showed little to no homologous pairing, fewer than 15% of 5S loci had paired chromosomes. As the nuclei progressed through meiotic prophase I, wild-type chromosomes initiated pairing and maintained high levels of pairing through the pachytene zones. In syp-1(me17) because there is no SC formed, mutant chromosomes remained mostly unpaired throughout the germline (Figures 4A and 4B). Pairing levels in csn-2 mutants never exceeded 20% of the 5S loci paired in any zone, indicating the majority of the chromosomes were unpaired. Overall, csn-2 and syp-1(me17) mutants exhibited similar pairing defects throughout meiotic prophase I (Figure 4A and 4B, Table S1 for n values and S2 for statistics). In contrast to csn-2 mutants, csn-5 mutants initiated pairing similarly to wild-type. Since the transition from mitosis to meiosis is occurring earlier in csn-5 mutants, pairing initiated at zone 2, compared to zone 3 in wild-type (Figure 4A). In zone 4, csn-5 mutants showed a reduction in the percent of nuclei with paired chromosomes, but the levels were intermediate between those observed in wild-type and syp-1 or csn-2 mutants. The percent of nuclei with paired chromosomes for the csn-5 mutant remained higher than the csn-2 mutant for zones 5 and 6. csn-6 showed an intermediate phenotype with low pairing levels as meiosis initiated (similar to csn-2) that then increased (similarly to csn-5), but never exceeded wild-type pairing levels. Meiotic nuclei of csn-2; csn-5 double mutants tended to have low pairing levels overall: the pairing levels in late pachytene nuclei were similar to csn-5 and statistically different from csn-2. When taken together these findings are consistent with a view where defects in SC assembly perturb pairing stabilization. The percent of nuclei with linear SYP-1 (Figure 2B–E) frequently exceeded the percent of nuclei paired. Therefore these data suggest that SYP assembled in a linear manner on chromosomes in csn mutants cannot support pairing stabilization. This SC-like localization (linear SYP-1) likely represents non-homologous synapsis and/or SYP assembly between sisters.

Meiotic recombination and crossover formation are perturbed in csn mutants

In mutants that do not form the SC, events downstream of pairing and SC assembly such as meiotic recombination are perturbed [54]. We expected the csn mutations would have a similar effect on recombination. RAD-51 is a strand exchange protein used as an indirect marker for DSB formation and subsequent repair in C. elegans [4]. The gonads were divided into zones as previously described and the numbers of RAD-51 foci per nucleus were counted (Figure 5A and Table S3 for n values and statistics).

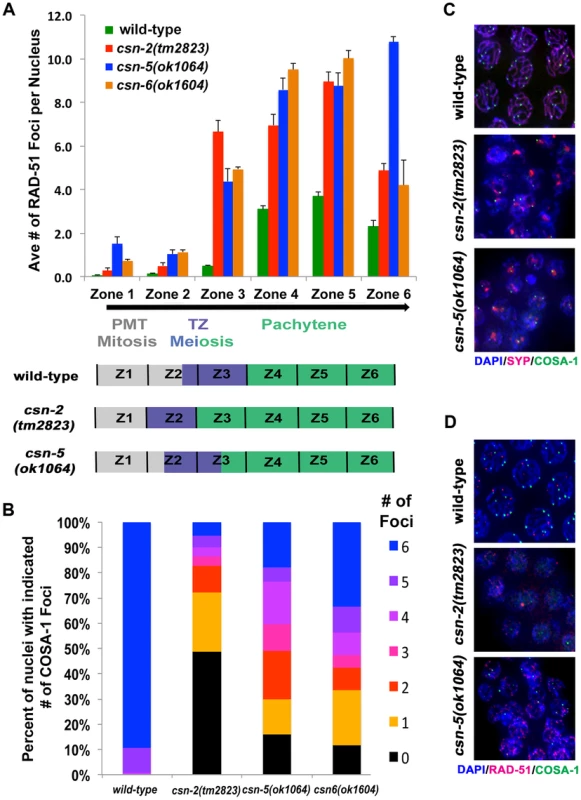

Fig. 5. Accumulation of recombination intermediates and reduced crossover formation in csn mutants.

A) Analysis of RAD-51 foci in wild-type compared to csn mutants. Position along the x-axis refers to the zone in the gonad (Figure 4). RAD-51 foci accumulate upon entrance to meiosis in csn mutants. Numbers of nuclei counted and p-values can be found in Sup. Table 3. Schematic representation of the timing of meiotic stages relative to zones scored in the csn mutants compared to wild-type. B) Quantitative analysis of COSA-1 foci in late pachytene of the wild-type and zone 6-like section of the csn mutants color code for number on COSA-1 is at right. Number of designated crossovers marked by COSA-1 is reduced. Number of nuclei scored: wild-type n = 123, csn-2 n = 111, csn-5 n = 94, csn-6 n = 78 p<0.0005 for comparison between wild-type and mutants and csn-2 to csn-5 or csn-6, p = 0.13 for csn-5 to csn-6, Mann Whitney Test, C) Micrograph images of COSA-1 foci (green), chromosomes DAPI (blue), and SYP-1 (red) in wild-type and csn mutants. D) Micrograph images of RAD-51 foci (red), COSA-1 foci (green), and chromosomes DAPI (blue) in wild-type and csn mutants. Images are projections through three-dimensional data stacks. Scale bar is 2 µm. Mitotic nuclei in zones 1 and 2 showed very low levels of RAD-51 both in wild-type and csn-2 mutants. csn-5 and csn-6 mutants exhibited slightly increased levels of RAD-51 foci in mitotic nuclei. RAD-51 foci levels increased at the entrance to meiosis in all genotypes tested, as expected from the induction of meiotic DSBs. The increase in RAD-51 foci/nucleus occurred earlier in csn mutants, likely due to the fact meiotic entry occurred earlier. Despite the similarity of RAD-51 localization patterns in the distal part of the germline, the overall levels of RAD-51 foci in early prophase were about 2-fold increased in csn mutants compared to wild-type. The levels of RAD-51 foci in the csn mutants remained higher than wild-type in zones 5–6, indicating the repair of DSBs was affected. In late pachytene, we observed a difference between csn-2 and csn-6 vs. csn-5 mutants: csn-5 mutants maintained RAD-51 foci at high levels, while they decreased in csn-2 and csn-6 mutants.

In C. elegans, one obligatory crossover is observed per chromosome pair [4]. COSA-1, a conserved cyclin related protein, localizes to crossovers and can be used to monitor the number of designated crossovers per nucleus (normally six, one for each wild-type bivalent formed) (Figure 5C and D). A reduction in COSA-1 foci suggests a defect in crossover formation. We tested the csn mutants using a GFP-tagged COSA-1 [58] to determine if crossover formation was affected. COSA-1 foci were measured at the last zone of late pachytene (as in [58]). Wild-type nuclei had an average of 5.8±0.04 COSA-1 foci (10% of nuclei with less than 6 foci), indicating designated crossovers had been properly formed (Figure 5C, see legend for statistics and n values). However, in the csn-2 mutant, 95% of the nuclei had less than six foci (1±0.16 foci per nucleus). In the csn-5 mutant, we observed a wider distribution of the number of COSA-1 foci observed, with 82% of the nuclei with less than six foci (2.8±0.21 foci per nucleus,). In the csn-6 mutant, we observed similar distribution to that of csn-5, with 67% of the nuclei with less than six foci (an average of 3.4±0.23 foci per nucleus). The average numbers of COSA-1 foci were significantly different between the csn-2 and csn-5 or csn-6 mutants. These data suggest a role for CSN/COP9 in crossover formation.

Apoptosis is increased in csn-2 and csn-5 mutants and dpMPK-1 levels are reduced

In synapsis-defective mutants lack of synapsis [59], as well as an accumulation of DSBs [4] results in increased apoptosis at late pachytene [54]. CED-1, is expressed during the process of engulfment; a mechanism of clearing apoptotic corpses from the germline in late pachytene. Thus, the fusion protein ced-1::GFP, exclusively surrounds apoptotic nuclei and is used as a marker to detect apoptosis.

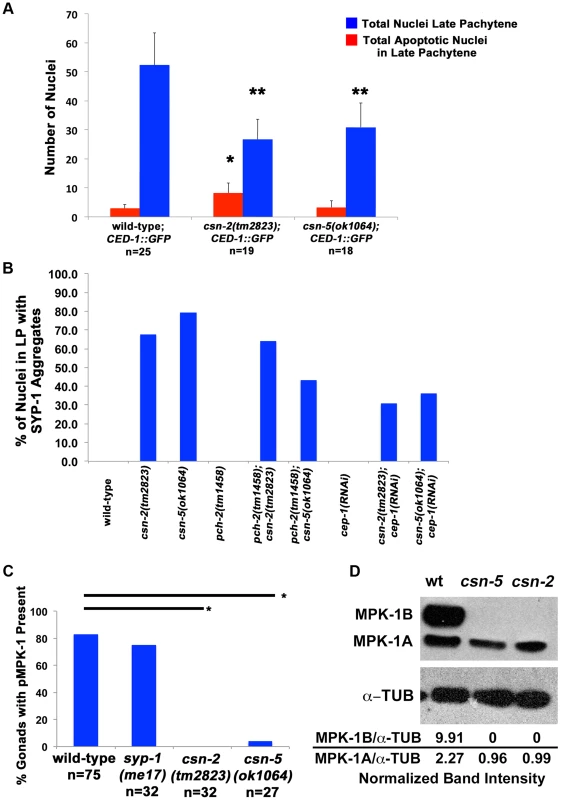

Both csn-2 and csn-5 mutants had lower average numbers of nuclei in late pachytene (Figure 6A wild-type average = 52.2; csn-2 = 26.7; and csn-5 = 30.9). However, only csn-2 had a significant increase in apoptosis (4-fold) while csn-5 had apoptotic levels similar to wild-type (Figure 6A wild-type average = 2.96; csn-2 = 8.2; and csn-5 = 3.3 apoptosis levels were not examined in csn-6 mutants). When normalized for the number of nuclei in late pachytene, both mutants showed increased apoptosis, and, as expected, csn-2 mutants showed a larger increase. This is the more appropriate analysis since csn mutants have less germline nuclei.

Fig. 6. Apoptosis and MPK-1 expression are altered in csn mutants.

A) Quantification of the number of nuclei with CED-1::GFP present in late pachytene of the C. elegans gonad. Red bars represent the total number of apoptotic nuclei in the late pachytene region. The blue bars represent the total number of nuclei in the late pachytene region. Apoptosis is increased in csn-2 mutants, but not in csn-5 mutants, *pMW<0.0005. There is also a reduction of overall nuclei in the late pachytene region of the gonad in both csn mutants, **pMW<0.0005. wild-type n = 25 gonads; csn-2 n = 19; and csn-5, n = 18, B) Analysis of SYP-1 aggregate phenotype in csn mutants and apoptosis checkpoint double mutants. Bypassing the apoptotic checkpoints reduces the number of nuclei with aggregates. Total number of nuclei counted and p-values can be found in Sup. Table 5. C) Quantification of dpMPK-1 expression via IF analyses. csn mutants lack MPK-1 staining in late pachytene and in diakinesis, *pFET<0.0005. wild-type n = 75, csn-2 n = 32, csn-5, n = 27, syp-1(me17) n = 32, D) Western Blot confirming the lack of expression of MPK-1B in csn mutants. MPK-1A is mostly somatic and MPK-1B is germline specific. Normalization values (α-MPK-1/α-TUB) shown are the average of 3 different experiments. Normalized intensities: wild-type 2.27±1.03, csn-2 0.96±0.42 and csn-5 0.99±0.09. There are two apoptotic checkpoints in C. elegans meiosis that are activated by unsynapsed chromosomes: the synapsis checkpoint mediated by PCH-2 [59] and the meiotic recombination checkpoint mediated by CEP-1/p53 [60]. We investigated whether removing these two genes could bypass the DNA damage/synapsis checkpoint leading to apoptosis in the csn mutants. pch-2(tm1458); csn-2(tm2823) and pch-2(tm1458); csn-5(ok1064) double mutants were generated and cep-1(RNAi) was performed on the csn mutants. Overall gonad length, number of oocytes in diakinesis, and the number of nuclei containing aggregates were measured. If increased apoptosis in late pachytene was the reason for the severe reductions in oocyte numbers, in csn mutants, then bypassing the checkpoint function should increase the numbers of diakinesis nuclei and increase the overall size of the gonad. We observed no change in overall gonad length (Table S4) between the single csn mutants and the corresponding double mutants, nor any increase in oocytes in diakinesis in young adults (one day post-L4, Figure 3C). Since clearing apoptotic corpses may be slow, we scored the same genotypes two days later, giving the opportunity for accumulation of cells (in double mutants) otherwise destined for apoptosis (csn single mutants). In csn-5 mutants overall gonad length decreased with age, possibly due to the defects in mitotic proliferation (less nuclei there are, the gonad gets shorter). However, both csn-5; pch-2 and csn-5; cep-1 mutants showed increased gonadal size compared to csn-5 single mutants (almost double the size, table S4). These data indicates that both the synapsis and the DNA damage checkpoint are activated in csn-5 mutants and are clearing nuclei through apoptosis.

Next, we assayed how removing the DNA damage and synapsis checkpoints would affect SC morphology in csn mutants. For this analysis we scored two categories: nuclei with linear SYP-1 localization and nuclei with aggregates (with our without other forms of SC). We measured the percent of nuclei with aggregates in double mutants with perturbed apoptotic machinery compared to single mutants. csn-5(ok1064); pch-2(tm1458), csn-2(tm2823); cep-1(RNAi), and csn-5(ok1064); cep-1(RNAi) double mutants exhibited a decrease (2-fold) in the number of nuclei with SYP-1 aggregates in late pachytene compared to the respective single csn mutant (Figure 6B and Table S5 for statistics). Therefore, nuclei with linear SYP were more frequently found in double mutants (in which the checkpoints are removed), indicating that functional checkpoints are associated with reduction in nuclei with linear SYP and promoting the aggregation of SYP proteins.

Given the known physical interaction between CSN-5 and MPK-1, a MAPK signaling protein [61], [62], and the substantial pachytene arrest (defects in progression from pachytene to diplotene) observed in csn mutants, we examined whether MAPK signaling was disrupted in csn mutants. Phosphorylated MPK-1 (dpMPK-1), the active form of MPK-1, is found in two distinct regions of the germline: late pachytene and late diakinesis. Nuclei of mpk-1 null mutants completely arrested at mid-pachytene and no oocytes were observed [63]. However, when only MPK-1 phosphorylation is eliminated (let-60 mutants) limited pachytene arrest occurred and oocyte numbers were severally reduced [64]. The increase of dpMPK-1 pachytene serves as a signal for pachytene progression. The diakinesis dpMPK-1 is required for maturation of oocytes [65], [66]. Using an antibody for phosphorylated MPK-1, we stained wild-type and csn mutant gonads. None of the csn-2 mutants examined had dpMPK-1 staining in late pachytene while only 3% of the csn-5 mutants had dpMPK-1 staining. In contrast, 82% of wild-type and 75% of syp-1(me17) gonads had dpMPK-1 staining (Figure 6C). MPK-1 has two isoforms in C. elegans, MPK-1A (43.1 kD) which is mostly somatic and MPK-1B (50.6 kD) is germline specific [60], [63]. We quantified the intensity of the bands and normalized to the tubulin controls (Figure 6D). In wild-type, both isoforms were detected with MPK-1A having an average normalized intensity of 2.27. The MPK-1A band was detected in both csn mutants (csn-2 = 0.99 and csn-5 = 0.96 normalized intensities), although it was 2-fold lower in both mutants. The germline MPK-1B had an intensity of 9.91, but was not detected in either csn mutant (Figure 6D). These data indicate that csn mutants lead to reduced MAPK/MPK-1 signaling which almost completely blocks pachytene exit and severely reduces oocyte numbers. This data is consistent with the observation that removing apoptosis checkpoints (pch-2 or cep-1) could not increase oocyte numbers in csn mutants: even if more nuclei survived apoptosis, they could still not exit pachytene arrest in the absence of dpMPK-1.

Decreasing neddylation and ubiquitination modify the phenotypes observed in csn mutants

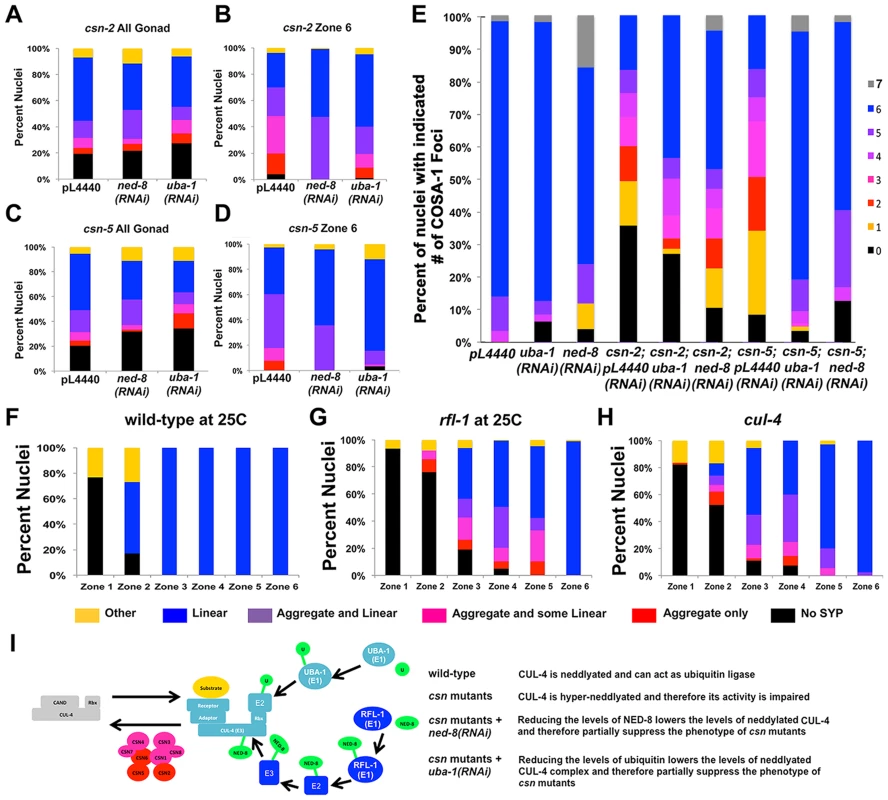

We have shown that synapsis (SC assembly) and recombination are perturbed in three csn mutants. The main role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome is in deneddylation of CRLs. Therefore, the csn mutant phenotypes could be attributed to the increased neddylation in the absence of a functional CSN/COP9 signalosome. The effect of complete absence of neddylation on the germline cannot be examined since null mutants in ned-8, the only gene encoding for the small modifying protein NED-8, are larval lethal. To test the hypothesis that over neddylation leads to the phenotypes described we have decreased the levels of neddylation via RNAi for ned-8 in csn-2 and csn-5 mutants. As seen in Figure 7B and D, (detailed distribution in Figure S6 and statistics in Table S6), ned-8(RNAi) partially suppressed the synapsis defects of csn mutants (pL4440 = empty vector control vs. ned-8(RNAi) on csn-2 p<0.001, on csn-5 p = 0.002, Fisher's Exact Test). More strikingly the levels of designated crossover (COSA-1) of csn mutants were partially restored (Figure 7E). Since CSN/COP9 signalosome typically deneddylates CRLs, which are ubiquitin ligases, the csn mutant phenotypes could also potentially be suppressed by reducing ubiquitination levels. As with neddylation, null mutants in genes essential for the ubiquitination pathway die prior to the adult stage and cannot be used in our studies. We have used RNAi for the sole E1 ubiquitin ligase of C. elegans, UBA-1, to test the hypothesis that the phenotypes of csn mutants can be attributed to increased ubiquitination. As with neddylation, uba-1(RNAi) partially suppressed both the defects in SC assembly (Figure 7 B and D) and the crossover defects of csn mutants (Figure 7E). If imbalance of neddylation is the cause of the phenotype observed in csn mutants, hyper-neddylation (csn mutants) and hypo-neddylation (mutants in the NED-8 pathway) will lead to similar phenotypes. The ned-8(RNAi) is weak; it does not lead to increased lethality although the null allele has a lethal phenotype. Therefore, it is not surprising that ned-8(RNAi) on wild-type did not lead to any phenotype. However, examination of an E1 NED-8 ligase (rfl-1) revealed defects in SC assembly reminiscent of the csn mutant phenotype (Figure 7G), defects not observed in the control (Figure 7F). Finally, we sought to identify the E3 CULLIN ligase, which is the target of CSN/COP9 signalosome. This analysis is limited because many mutants of cul genes are embryonic or larval lethal. We have identified one cul-4 mutant allele (a C-terminal truncation) that exhibited mild defects in SC assembly, including aggregation of SYP-1 (Figure 7H). CUL-4 is therefore, a possible CSN/COP9 signalosome target. This genetic analysis is consistent with a canonical role for CSN/COP9 signalosome in the CRL pathway: regulating CUL-4 via denaddylation and keeping the balance between neddylation and denaddylation.

Fig. 7. csn mutant genetically interact with the ubiquitination-neddylation pathway in the regulation of SC assembly and recombination.

A–D) Quantification of SYP-1 aggregates. A and C are data from all gonad, while B and D is from late pachytene nuclei. Percent of nuclei with: no SYP-1 (black), linear SYP-1 (blue), aggregated SYP-1 (purple pink and red) and other (yellow), zones as in Figure 2A, n nuclei scored for whole gonad csn-2: with pL4440 = 2023 with ned-8(RNAi) = 430, with uba-1(RNAi) = 1121, csn-5: with pL4440 = 2096, with ned-8(RNAi) = 441, with uba-1(RNAi) = 1014. E) Quantitative analysis of COSA-1 foci in late pachytene wild-type: Percent of nuclei with: zero (black) one (orange), two (red), three (pink) four (magenta), five (purple), six (blue) and seven (gray), n nuclei scored for pL4440 = 57, with ned-8(RNAi) = 47, with uba-1(RNAi) = 25, csn-2: with pL4440 = 168, with ned-8(RNAi) = 66, with uba-1(RNAi) = 126, csn-5: with pL4440 = 152, with ned-8(RNAi) = 47 with, uba-1(RNAi) = 83, pL4440 = empty vector control vs. ned-8(RNAi) on csn-2 or csn-5 p = 0.002, p<0.001, Fisher's Exact Test, pL4440 vs. uba-1(RNAi) on csn-2 or csn-5 p<0.001 Mann Whitney Test). F–H) Quantification of SYP-1 aggregates in zones of the gonad for the indicated genotypes, as performed in figure, number of total nuclei scored: wild-type 25 n = 641, rfl-1 at 25 n = 1674, cul-4 n = 542 2, I) Schematic representation of the pathway examined in the experiment. Taken together, these data indicate the CSN/COP9 signalosome has multiple roles in meiosis: the signalosome affects the number of germline nuclei, SC assembly and stabilization, recombination, MAPK signaling and promoting pachytene exit.

Discussion

CSN/COP9 is required for chromosome synapsis, pairing and recombination during C. elegans meiosis

The CSN/COP9 signalosome has diverse and well-documented somatic functions, yet the understanding of its role in meiosis is limited [28]. Studies of the C. elegans and D. melanogaster CSN/COP9 indicate it plays a critical role in the regulation of Vasa/P-granule proteins in the germline [42], [55], [67]. Here, we show CSN/COP9 has a previously unknown meiotic function: it is essential for proper SC assembly, independent of its P-granule role in the germline. We demonstrate that events following SC assembly (e.g., stabilization of homolog pairing interactions and the repair of meiotic DSBs) are perturbed as well. The three csn mutants show similar, but not identical effects on these processes; in the absence of CSN/COP9, the SYPs (CR proteins) aggregate. In C. elegans, stabilization of pairing interactions is absolutely dependent on SC formation and independent of DSB formation and repair [57]. Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that the pairing defects observed in CSN/COP9 mutants stem from defects in SC formation. The limited amount of SC that assembles on chromosomes in csn mutants cannot support wild-type levels of stabilization of pairing interactions (by FISH analysis). In the absence of fully stabilized pairing interactions, unresolved recombination intermediates (marked by RAD-51) accumulate. This leads to a reduction in the numbers of designated crossovers (marked by COSA-1 foci) in csn mutants and an elevation of apoptosis. The magnitude of these phenotypes in csn-2 mutants closely resembles that of syp null mutants, supporting our model that the later meiotic defects (pairing and recombination) stem from an inability to form functional SC. The exact magnitude of the effects on recombination and pairing initiation is different between the mutants and may point to additional roles of components of the CSN/COP9 signalosome in pairing and recombination (more discussion below). Importantly, all three csn mutants we have examined affect synapsis, pairing, and recombination and therefore we are confident in our claim for a role for the CSN/COP9 complex in these key meiotic events.

CSN/COP9 is required for normal levels of germline proliferation, MPK-1 activation and pachytene exit

Consistent with previous studies in C. elegans utilizing RNAi [51], [52] the three csn mutants have a reduced gonad size. Our data suggest this reduction is due to a proliferation defect, as the number of mitotically dividing nuclei in the pre-meiotic tip is reduced in the csn mutants. Drosophila csn4 and csn5 mutants cannot stabilize Cyclin E leading to defects in cell cycle progression of mitotically proliferating germline nuclei [46]. This suggests a conserved function of the CSN/COP9 signalosome in pre-meiotic germline proliferation.

Once nuclei of csn mutants enter meiosis, chromosomes cluster to one side of the nucleus as in wild-type; unlike wild-type however, a portion of these nuclei do not re-acquire the normal dispersed chromosomal organization as they progress through meiosis (Figure 1B and C). This phenotype of persistent polarized chromosome organization is reminiscent of syp null mutants during meiotic progression. This finding, together with the observation that csn mutants do initiate meiotic recombination and form some designated crossovers, is consistent with meiotic progression from leptotene to pachytene in these mutants. However, unlike syp mutants, csn mutants produce almost no diakinesis/oocyte nuclei. Reduced oocyte production would results from the decrease in numbers of germ cells, yet the effect on oocyte production is greater than expected from the reduction in number of pachytene nuclei destined to be oocytes. We have found MAPK signaling (dpMPK-1) is reduced in csn mutants. MAPK signaling is essential for pachytene progression [63] and so we infer that reduced dpMPK-1 levels are likely the primary contributor to the severe reduction in oocyte numbers in csn mutants. As synapsis defective mutants (e.g., syp-1) still exit pachytene and form oocytes in comparable levels to wild-type, the lack of MAPK signaling in the csn mutants defines another function for the CSN/COP9 complex and is not a secondary effect of the synapsis defects. Since CSN-5 physically interacts with MPK-1 [61], [62], the absence of MPK-1 phosphorylation, may be due to the absence of this interaction. The role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome in pachytene exit seems to be conserved, as similar to our observation, Drosophila csn8 and csn4 mutants arrest at the pachytene-diplotene transition [68], [69].

The relation between the linear and the aggregate forms of the CR proteins

In C. elegans, CR/SYPs assembly can be misregulated in certain meiotic mutants without forming aggregates [7], [9], [11], [14]. These aberrant forms of SC assembly appear to be fully formed SCs that are assembled in the wrong chromosomal context. The situation found in the csn mutants is different: in addition to aberrant SC assembly (short stretches) ∼50% of nuclei contain one SYP aggregate. In C. elegans, lack of any one of the four SC protein results in elimination of the other SYPs without their aggregation [13], indicating that mechanisms exist to remove SYPs not bound to DNA. csn mutants are therefore likely perturbed in mechanisms designed to clear aggregated SYPs, and assemble a “SC-like” structure which is invisible to the degradation machinery. In yeast, the CR protein is continually loaded on the SC, even in mid-prophase [70]. If a similar rapid exchange of SYPs occurs during C. elegans meiosis, SC assembly defects (problems in SC assembly upon meiotic entry) and SC stabilization defects (throughout pachytene) are related, due to continuous assembly of SC protein occurring throughout prophase. This may explain why a mutant that affects SC assembly (csn-5) was retrieved in an enhancer screen for a mutant showing SC disassembly defects.

Although it is likely that the formation of CR aggregates reflects an aberrant form of SC assembly, it is not clear if these aggregates are the problem or an attempt to solve a problem. In other words, it could be that the CRs which cannot be properly loaded onto chromosomes aggregates and therefore would not be available for SC formation. Alternatively, CRs may be loaded on to chromosomes, but then identified as aberrant CR, removed and then form aggregates which acts as reservoirs of CR proteins waiting to be re-loaded. Since linear (and non aggregated CR) seem to be a better predictor for failed meiosis, we tend to favor the hypothesis were CR aggregates are formed in response to attempts to correct an aberrantly formed SC. First, mutants with more linear SYP-1 (csn-2 and csn-6) in early meiotic stages (zone 3) show more severe defects in pairing compared with a mutant with a higher percentage of SYP-1 aggregation (csn-5). Second, nuclei with linear SYP-1 are preferentially selected for elimination by apoptosis. Lastly, if aggregation is only an assembly defect, then the percent of aggregated nuclei should increase as meiosis progresses, which does not occur. This is more consistent with a model of SYP shuttling between an assembled and an aggregated from.

We have shown that the percent of nuclei undergoing apoptosis is increased in both csn-2 and csn-5 mutants. This active elimination of nuclei by apoptosis reduces the size of the germline over time (csn-5; pch-2 gonads were longer compared to csn-5 single mutant at day 3). Both the synapsis checkpoint and the DNA damage checkpoints contribute to the elimination of nuclei in csn-5 mutants. Checkpoint activation is associated with an increase in aggregated SYP-1. However, while the percent of nuclei with aggregated SYP-1 is reduced by removing both checkpoints, the removal of the synapsis checkpoint (pch-2 mutant) affects only the csn-5 mutants. Pairing levels in csn-5 mutants are higher than observed in csn-2 mutants; it is possible that csn-5 mutants attempt more to synapse (and fail) more compared to csn-2 mutants, which leads to a robust activation of the synapsis checkpoint. PCH-2 serves as a kinetic barrier for synapsis, slowing down synapsis [71]. Therefore, it is possible that elimination of pch-2 in the csn-2 background increases the percent of linear SYP-1 merely by increasing the speed of assembly. Although this is possible, the removal of cep-1, which is not known to act like pch-2, has the same effect on the reduction of nuclei with SYP-1 aggregates. We propose that the reduction in fraction of nuclei with SYP-1 aggregation in a checkpoint mutant is due to the removal of the apoptotic program. This may be done directly by inducing changes in SC morphology or by activating downstream meiotic arrest providing more time for SC elongation. Alternatively, it could be done directly by preferentially eliminate nuclei with linear SYP-1.

How CSN/COP9 regulates chromosome synapsis

There are three known examples of PC-like structures in C. elegans mutants: cra-1; spo-11 double mutants [14], pgl-1 mutants at 25°C and higher [20] and dynein mutants in early prophase [21]. Our analysis thus far is consistent with a different function for the CSN/COP9 signalosome; aggregates in csn mutants are found in the presence of DSBs (unlike cra-1), at normal growth temperatures (unlike pgl-1 mutants], and throughout the germline (unlike dynein mutants). Therefore, we propose that CSN/COP9 participates in SC assembly in a novel manner. The signalosome's role is not merely due to promoting SYP degradation; we confirmed using several assays that csn mutants do not show increased SYP-1 levels.

Pathways of SC assembly involve post-translational modifications of SC proteins. These modifications could facilitate CR protein association with chromosomes and prevent their aggregation. In yeast, it was shown sumoylation promotes lateral element [72] and CR [73] assembly. Mouse SC assembly is regulated by phosphorylation of lateral element proteins [74]. In C. elegans, SYP-1 and SYP-2 appear to be post-translationally modified, however, the precise identities of these modifications is unknown [13]. All four SYPs contain potential sites for phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation. In C. elegans, an evolutionarily conserved ubiquitin/sumo modifier [75] is linked to SC disassembly, but is not required for SC assembly [76].

The discovery that the CSN/COP9 complex is required to prevent SYP aggregation raises the question of whether CSN/COP9 is involved in post-translational modification of the SYPs to prevent their aggregation. SYP aggregates contain all four SYP proteins, hence one aggregation-prone SYP may lead to the capture of all SYPs. The CSN/COP9 complex's activity in deneddylation has been well documented, but it also possesses Ser/Thr kinase and deubiquitination associated activities [28]. CULLIN RING E3 ligases (CRLs) are the most well studied of the CSN/COP9 substrates [37], [38]. The current literature supports a model where the CSN/COP9 signalosome destabilizes the CRL complexes by deneddylation which inhibits CRL activity [39], [41]. However null signalosome mutants do not show stabilization of CRL. This suggests that both hyper and hypo-neddylation is detrimental for CRL function. This model is consistent with our findings that RNAi for neddylation and ubiquitination can partially suppress two csn mutant phenotypes. Moreover, we have identified an E1 NED-8 ligase (rfl-1) that exhibits similar SYP-1 localization defects to these of csn mutants. Our data also suggest that CSN/COP9 acts through CUL-4 to regulate SC assembly. If so, one role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome could be removing NED-8 to regulate CUL-4, which in turn regulates the SYPs by ubiquitination, supporting their proper assembly. In the absence of such modification, SYPs would aggregate. In this view, CSN/COP9 would repress SYPs aggregation indirectly, by inhibiting CRL monoubiquitination of SYPs which promotes SC assembly.

CSN subunits acting outside the CSN/COP9 complex

The CSN/COP9 complex is composed of 7 to 8 subunits, depending on the organism [28]. The CSN5 subunit is responsible for the deneddylation activity of the CSN/COP9 complex, but cannot function in deneddylation outside the holoenzyme [77], [78]. Smaller sub-complexes, with variable subunit composition have been isolated as well: CSN4-7 Arabidopsis and Drosophila [79], [80] and CSN-4-5-6-8 in mammals [81]. Mutant analyses have indicated the loss of any one subunit leads to signalosome disassembly [82], [83]. The csn mutant phenotypes are not always identical, suggesting functions outside the CSN/COP9 signalosome for individual subunits. For example: Drosophila csn4, csn5 and csn8 mutations cause larval lethality, but they die in different larval stages [42], [68], [77], [80]. Furthermore, S. pombe csn1 and csn2 mutants show defects in meiotic entry and meiotic recombination, while mutants in the other subunits have no clear meiotic phenotypes [84]. CSN5 [39], [85] and CSN2 [86] are the only subunits shown to act outside CSN/COP9 in vivo.

We have shown that csn-2, csn-5 and csn-6 mutants all lead to defects in SC assembly, a reduction in pairing, and increase in DSB repair defects in meiotic recombination. However, the magnitude of these effects varies (see summary in Figure S7). Pairing analysis show that the csn-2 mutant almost mimics a syp null mutant, while the csn-5 and csn-6 mutants show milder pairing stabilization defects (5S FISH) and double the numbers of designated crossovers (COSA-1) compared to the csn-2 mutant. The SC is driving the stabilization of early prophase pairing interactions (zone 2–3), while later events (zone 6) are also promoted by the stabilizing role of crossovers, which are likely higher in the csn-5 and csn-6 mutant (COSA-1). Therefore, as for pairing and crossover formation, csn-5 and csn-6 both display milder phenotypes compared to csn-2. However, when examining synapsis (SYP-1) and the kinetics of repair of recombination intermediates (RAD-51), csn-2 and csn-6 cluster together with milder phenotypes compared to csn-5. It is hard to reconcile this model with a strictly linear role for the CSN/COP9 signalosome affecting synapsis, pairing, recombination progression and ending at crossover formation. It is likely that the picture is more detailed and complex. We propose that in addition to the central role of the CSN/COP9 signalosome in SC formation (which affects recombination and pairing stabilization) additional roles exist in down-regulating pairing initiation and promoting crossover formation, independently of the SC. These different roles may stem from alternative complex formation, as was shown in other organisms. One possible model would involve an inhibitory role for CSN-5-CSN-6 on pairing stabilization outside the CSN/COP9 holocomplex. CSN-5 and CSN-6 have been shown to physically interact and form a sub module in the CSN/COP9 complex [78]. We do have some support for a role for CSN-5 in down-regulating pairing initiation: as expected by this model, csn-5 is epistatic to csn-2 as for pairing interactions.

Identifying the precise role of each subunit and sub-complexes in meiosis will require more extensive analysis of each subunit. The work presented here is but a first step in this direction. It is intriguing that both neddylation [43] and deneddylation (this study) have such profound effects on crossovers and SC formation. These studies strengthen our claim that the balance between neddylation and deneddylation is key to accurate meiosis and these processes are likely to be evolutionarily conserved.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Most C. elegans strains were cultured under standard conditions at 20°C [87]. Several strains (in bold) were maintained at 15°C and experimentally cultured at 26°C. N2 Bristol worms were utilized as the wild-type background. The following mutations and chromosome rearrangements were used:

LGI: cep-1(ep347), csn-2(tm2823), glh-1(gk100), hT2[bli-4(e937) qIs48]

LGII: pch-2(tm1458), cul-4(ok1891)

LGIII: rfl-1(or198)

LGIV: csn-5(ok1064), csn-6(ok1604), kgb-1(um3), nT1[qIs50]

LGV: syp-1(me17)

The following transgenic lines were used: meIs8(GFP::COSA-1), smIs34 [ced-1p::ced-1::GFP+rol-6(su1006)] and meIs9[unc-119(+)pie-1promoter::gfp::SYP-3]; unc-119(ed3)III [88]. All strains were outcrossed 6 times except glh-1(gk100) which was outcrossed twice, pch-2(tm1458) outcrossed 5 times and cul-4(ok1891) which was outcrossed once.

Analyses of the csn allele transcripts by RT-PCR

In order to determine if the deletions in the csn mutants are in-frame or out of frame, we conducted RT-PCR analyses. This was done using the Superscript III OneStep RT PCR kit (12574-026, Life Technologies) and the primers TGAATACGAAGATGATAGTGGCT and CAATACGCTCTGCCCAAACA for csn-2 and CGAAGGTGCTTTTGCATCCTTTGG and GCAGATGGTCTTGGAACGTCTG for csn-5. Our analysis reveals that csn-2(tm2823) is an in-frame deletion. The csn-2(tm2823) transcript lacks exon 2, and results in a 139 amino acid deletion of the peptide sequence. Although this deletion is in-frame, 28% of the protein is missing, including half of the PAM domain. We did not assess whether the total levels of transcript in this mutant are reduced. csn-5(ok1064) is a deletion that includes the promoter region and half of the coding region. Translation from the first in-frame AUG will lead to 75 amino acid peptide, a deletion of 80% of the protein, including the catalytic MPN domain. We have not yet succeeded in amplifying a csn-5 transcript form csn-5(ok1064), suggesting that csn-5(ok1064) lacks a functional promoter. The csn-6(ok1604) is in frame deletion that includes deletion of half of the gene. The csn-6(ok1604) transcript is spliced from the middle of exon 1 to the start of exon 3, when exon 2 is skipped, resulting in deletion of coding sequence expected to lead to 193 amino acid deletion of the peptide sequence. Therefore, 45% of the protein is missing, including most of the MPN domain. We did not assess whether the total levels of transcript in this mutant are reduced.

Immunostaining and microscopy

Adult hermaphrodites 20 h post-L4 were dissected to release gonads. DAPI and immunostaining was performed as described in [4]. For transgenic lines utilizing GFP fusions, fixation was in methanol for 1–5 minutes, then washed and prepared for microscopy as in [4]. Whole mount worms were prepared by Carnoy's Fixation. Antibodies were used at the following dilutions: α-SYP-1, 1∶500; α-SYP-4, 1∶500; α-HIM-3, 1∶500; α-HTP-3, 1∶500; α-RAD-51 1∶10,000; α-dpMPK-1 1∶500 (Sigma). The secondary antibodies used were: Alexa Fluor 488 α-mouse, Alexa Fluor 488 α-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 α-rabbit, Alexa Fluor 568 α-goat, Alexa Fluor 568 α-guinea pig (Invitrogen), and DyLight 594 α-goat (Jackson Immunochemicals, West Grove, PA).

The images were acquired using the DeltaVision wide-field fluorescence microscope system (Applied Precision) with Olympus 100×/1.40 - or 60× numerical aperture lenses. Optical sections were collected at 0.20-um increments with a coolSNAPHQ camera (Photometrics) and deconvolved with softWoRx software (Applied Precision). Gonadal and nuclei images are projections halfway through three-dimensional data stacks (Multiple 0.2-µm slices/stack), except of where full projections are indicated, and were prepared using softWoRx Explorer 1.3.0 software (Applied Precision) or FIJI [89].

Aggregates were defined as SYP signals with width larger than that of wild-type SC. When measured, even the smallest aggregates were larger than the larger SC width measured and above the average SC with plus 2 standard deviations. As indicated in the results section, these values were highly statistically significant (p≪0.001), indicating that our calling of SC aggregates was precise.

Quantitative analysis of the intensity of SYP-1 signals was performed on images taken from the same slide in the same exposure time. Images were analyzed using ImageJ [89]. This was performed under guided model option with a freehand polygon section in all Z-stacks of a particular SYP signal and to multiple gonads from each genetic background. We set a threshold of 250 for the max grey value being measured, to ensure that over-exposed images were not included in the analysis. Data for each nucleus is the sum of all the Z stakes in which the nuclei is detected on the DAPI channel. To obtain SYP-1 signal intensity, we subtracted the integrated intensity of the background of the same image from the SYP-1 integrated intensity to get the normalized integrated density [Nuclear (IntDen/Area) – Background (IntDen/Area)]. We presented the data as total integrated intensity ([Nuclear (IntDen/Area)−Background (IntDen/Area)]×Area of each nucleus) and also as IntDen/Area. The total integrated intensity is an indication of the total SYP-1 signal in each nucleus; the IntDen/Area is the average intensity of the SYP single in each nucleus. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were performed using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, 95% confidence interval.

Fecundity assay

To determine the fecundity of the csn mutants, single L4 worms were placed on seeded NGM plates and allowed to lay eggs for a 15 hr period. These worms were then moved to a fresh NGM plate and again allowed to lay eggs. This was repeated for a three day period. Eggs were counted for each genotype examined.

FISH and time-course analysis of chromosome pairing

The 5S FISH probe was generated as in [57] from a PCR fragment generated by amplifying C. elegans genomic DNA with the 5′-TACTTGGATCGGAGACGGCC-3′ and 5′-CTAACTGGACTCAACGTTGC-3′ primers. Fragments were labeled with fluorescein-12-dCTP (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Homologous pairing was monitored quantitatively as in [57]. The total number of nuclei scored per zone (n) from three gonads each for wild-type, csn-2 and csn-5 mutants. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were performed using the Fishers Exact Test, 95% confidence interval.

Time-course analysis for RAD-51 foci

Quantification of RAD-51 foci was performed for all seven zones composing the premeiotic tip to late pachytene regions of the germline as in Colaiacovo et al. (2003). The total number of nuclei (n) were scored per zone from three gonads each for wild-type, csn-2 and csn-5 mutants. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were performed using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, 95% confidence interval.

Time-course analysis for COSA-1 foci

Quantification of GFP::COSA-1 was carried out as in [58] with zone 6 selected to be analyzed. The total number of nuclei (n) were scored in zone 6 for 5 gonads. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were performed using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, 95% confidence interval.

Apoptosis

The csn mutants were introgressed to ced-1::GFP strain (smIs34 [ced-1p::ced-1::GFP+rol-6(su1006)]) to assess apoptotic levels as per [90]. Images were taken at 60× and nuclei which displayed CED-1::GFP localization were counted as well as the total number of nuclei in the bend region (late pachytene). 10 different gonads were quantified. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were performed using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, 95% confidence interval.

Western blotting

L4 homozygote larvae were picked and aged to adults. The mouse α-dpMPK-1 (Sigma) was used as a primary antibody (1∶1000). Mouse α-tubulin (1∶000; DSHB) was used as a loading control. Secondary antibodies used were α-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; 1∶10,000). PBST-5% milk was used for incubation and blocking. Quantification was done on FIJI [89].

RNAi screen

csn-5 (B0547.1) was identified in a RNAi screen on the akir-1 background for mutants affecting SC morphogenesis. Synchronized L1 larvae were placed on NGM+AMP+isopropyl-B-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) plates seeded with RNAi bacterial clones from the Ahringer C. elegans RNAi library [91] or pL4440 empty vector (control). Embryonic lethality was scored visually and clones exhibiting increased lethality as compared to controls were selected for replication and further analysis. We then conducted a fecundity study to determine if the reduction in live progeny was due to meiotic or developmental defects. Clones demonstrating a reduction in the number of eggs laid were selected for cytological screening.

RNAi feeding protocols

RNAi clones are ground 6 hours–overnight in LB+ampicillin (50 ug/ml). Cultures are then seeded onto IPTG plates (see above) and left to grow overnight [91]. Either synchronized L1 or L4 larvae were placed on the plates, left to develop to adults. These adults were subjected to cytological analyses or their F1 progeny scored for viability.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HassoldT, HUNTP (2001) To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics 2 : 280–291 doi:10.1038/35066065

2. HiroseY, SuzukiR, OhbaT, HinoharaY, MatsuharaH, et al. (2011) Chiasmata Promote Monopolar Attachment of Sister Chromatids and Their Co-Segregation toward the Proper Pole during Meiosis I. PLoS Genet 7: e1001329 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001329.s010

3. PageSL, HawleyRS (2004) the genetics and molecular biology of the synaptonemal complex. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20 : 525–558 doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.155141

4. ColaiácovoMP, MacQueenAJ, Martinez-PerezE, McDonaldK, AdamoA, et al. (2003) Synaptonemal Complex Assembly in C. elegans Is Dispensable for Loading Strand-Exchange Proteins but Critical for Proper Completion of Recombination. Developmental Cell 5 : 463–474 doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00232-6

5. ZetkaM, KawasakiI, StromeS (1999) Synapsis and chiasma formation in Caenorhabditis elegans require HIM-3, a meiotic chromosome core component that functions in chromosome segregation. Genes & …

6. CouteauF, NabeshimaK, VilleneuveA, ZetkaM (2004) A Component of C. elegans Meiotic Chromosome Axes at the Interface of Homolog Alignment, Synapsis, Nuclear Reorganization, and Recombination. Current Biology 14 : 585–592 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.033

7. CouteauF (2005) HTP-1 coordinates synaptonemal complex assembly with homolog alignment during meiosis in C. elegans. Genes & Development 19 : 2744–2756 doi:10.1101/gad.1348205

8. GoodyerW, KaitnaS, CouteauF, WardJD, BoultonSJ, et al. (2008) HTP-3 Links DSB Formation with Homolog Pairing and Crossing Over during C. elegans Meiosis. Developmental Cell 14 : 263–274 doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.016

9. Martinez-PerezE (2005) HTP-1-dependent constraints coordinate homolog pairing and synapsis and promote chiasma formation during C. elegans meiosis. Genes & Development 19 : 2727–2743 doi:10.1101/gad.1338505

10. SeversonAF, LingL, van ZuylenV, MeyerBJ (2009) The axial element protein HTP-3 promotes cohesin loading and meiotic axis assembly in C. elegans to implement the meiotic program of chromosome segregation. Genes & Development 23 : 1763–1778 doi:10.1101/gad.1808809

11. SmolikovS, EizingerA, HurlburtA, RogersE, VilleneuveAM, et al. (2007) Synapsis-Defective Mutants Reveal a Correlation Between Chromosome Conformation and the Mode of Double-Strand Break Repair During Caenorhabditis elegans Meiosis. Genetics 176 : 2027–2033 doi:10.1534/genetics.107.076968

12. SmolikovS, Schild-PrüfertK, ColaiácovoMP (2009) A Yeast Two-Hybrid Screen for SYP-3 Interactors Identifies SYP-4, a Component Required for Synaptonemal Complex Assembly and Chiasma Formation in Caenorhabditis elegans Meiosis. PLoS Genet 5: e1000669 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000669.t002

13. Schild-PrüfertK, SaitoTT, SmolikovS, GuY, HincapieM, et al. (2011) Organization of the Synaptonemal Complex During Meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics doi:10.1534/genetics.111.132431

14. SmolikovS, Schild-PrüfertK, ColaiácovoMP (2008) CRA-1 Uncovers a Double-Strand Break-Dependent Pathway Promoting the Assembly of Central Region Proteins on Chromosome Axes During C. elegans Meiosis. PLoS Genet 4: e1000088 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000088.t001

15. YuanL, PelttariJ, BrundellE (1998) The synaptonemal complex protein SCP3 can form multistranded, cross-striated fibers in vivo. J Cell Biol 142 : 331–339 doi:10.2307/1618785?ref = search-gateway:b71391caf6f755290e690dbd76f417a2

16. YuanL, BrundellE, HöögC (1996) Expression of the meiosis-specific synaptonemal complex protein 1 in a heterologous system results in the formation of large protein structures. Experimental Cell Research 229 : 272–275 doi:10.1006/excr.1996.0371

17. GoldsteinP (1986) The synaptonemal complexes of Caenorhabditis elegans: the dominant him mutant mnT6 and pachytene karyotype analysis of the X-autosome translocation. Chromosoma 93 : 256–60..

18. YangF, La Fuente DeR, LeuNA, BaumannC, McLaughlinKJ, et al. (2006) Mouse SYCP2 Is Required for Synaptonemal Complex Assembly and Chromosomal Synapsis during Male Meiosis. The Journal of Cell Biology 173 : 497–507.

19. PadmoreR, CaoL, KlecknerN (1991) Temporal comparison of recombination and synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66 : 1239–1256.

20. BilgirC, DombeckiCR, ChenPF, VilleneuveAM, NabeshimaK (2013) Assembly of the Synaptonemal Complex is a Highly Temperature-Sensitive Process that is Supported by PGL-1 during Caenorhabditis elegans Meiosis. G3 (Bethesda) pii: g3.112.005165v1 doi:10.1534/g3.112.005165

21. SatoA, IsaacB, PhillipsCM, RilloR, CarltonPM, et al. (2009) Cytoskeletal forces span the nuclear envelope to coordinate meiotic chromosome pairing and synapsis. Cell 139 : 907–919 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.039

22. ClemonsAM, BrockwayHM, YinY, KasinathanB, ButterfieldYS, et al. (2013) akirin is required for diakinesis bivalent structure and synaptonemal complex disassembly at meiotic prophase I. Mol Biol Cell 24 : 1053–1067 doi:10.1091/mbc.E12-11-0841

23. SmolikovS, EizingerA, Schild-PrufertK, HurlburtA, McDonaldK, et al. (2007) SYP-3 Restricts Synaptonemal Complex Assembly to Bridge Paired Chromosome Axes During Meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 176 : 2015–2025 doi:10.1534/genetics.107.072413

24. WojtaszL, DanielK, RoigI, Bolcun-FilasE, XuH, et al. (2009) Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, Two Conserved Meiotic Chromosomal Proteins, Are Depleted from Synapsed Chromosome Axes with the Help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet 5: e1000702 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000702.g014

25. HumphryesN, LeungW-K, ArgunhanB, TerentyevY, DvorackovaM, et al. (2013) The Ecm11-Gmc2 Complex Promotes Synaptonemal Complex Formation through Assembly of Transverse Filaments in Budding Yeast. PLoS Genet 9: e1003194 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003194.s008

26. ChamovitzDA, SegalD (2001) JAB1/CSN5 and the COP9 signalosome. EMBO reports 2(2): 96–101..

27. Bech-OtschirD, SeegerM, DubielW (2002) The COP9 signalosome: at the interface between signal transduction and ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Journal of Cell Science 115 : 467–473.

28. WeiN, DengX-W (2003) The COP9 signalosome. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19 : 261–286 doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.112449

29. KimT, HofmannK, Arnim vonAG, ChamovitzDA (2001) PCI complexes: pretty complex interactions in diverse signaling pathways. Trends Plant Sci 6 : 379–386.

30. CopeGA, SuhGSB, AravindL, SchwarzSE, ZipurskySL, et al. (2002) Role of predicted metalloprotease motif of Jab1/Csn5 in cleavage of Nedd8 from Cul1. Science 298 : 608–611.

31. GusmaroliG, FigueroaP, SerinoG, DengX-W (2007) Role of the MPN in COP9 Signalosome Assembly and Activity, and Their Regulatory Interaction with Arabidopsis Cullin3-Basd E3 Ligases. The Plant Cell 19 : 564–581 doi:10.2307/20076954?ref = search-gateway:783c5712e25bd4e9112a887c839bc6a2

32. WolfDA, ZhouC, WeeS (2003) The COP9 signalosome: an assembly and maintenance platform for cullin ubiquitin ligases? Nat Cell Biol 5 : 1029–1033 doi:10.1038/ncb1203-1029

33. MerletJ, BurgerJ, GomesJE, PintardL (2009) Regulation of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin-ligases by neddylation and dimerization. Cell Mol Life Sci 66 : 1924–1938 doi:10.1007/s00018-009-8712-7

34. PengZ, SerinoG, DengX-W (2001) Molecular Characterization of Subunit 6 of the COP9 Signalosome and Its Role in Multifaceted Developmental Processes in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 13 : 2393–2407.

35. PickE, GolanA, ZimblerJZ, GuoL, SharabyY, et al. (2012) The minimal deneddylase core of the COP9 signalosome excludes the Csn6 MPN - domain. PLoS ONE 7: e43980.

36. ChooYY, BohBK, LouJJW, EngJ, LeckYC, et al. (2011) Characterization of the role of COP9 signalosome in regulating cullin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol Biol Cell 22 : 4706–4715 doi:10.1091/mbc.E11-03-0251

37. PetroskiMD, DeshaiesRJ (2005) Function and regulation of cullin–RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6 : 9–20 doi:10.1038/nrm1547

38. ChibaT, TanakaK (2004) Cullin-based ubiquitin ligase and its control by NEDD8-conjugating system. curr protein pept sci 5 : 177–184.

39. WeiN, SerinoG, DengX-W (2008) The COP9 signalosome: more than a protease. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 33 : 592–600 doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.004

40. TianL, PengG, ParantJM, LeventakiV, DrakosE, et al. (2010) Essential roles of Jab1 in cell survival, spontaneous DNA damage and DNA repair. Oncogene 29 : 6125–6137 doi:10.1038/onc.2010.345

41. StratmannJW, GusmaroliG (2012) Many jobs for one good cop - the COP9 signalosome guards development and defense. Plant Sci 185–186 : 50–64 doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.10.004

42. DoronkinS, DjagaevaI, BeckendorfSK (2002) CSN5/Jab1 mutations affect axis formation in the Drosophila oocyte by activating a meiotic checkpoint. Development 129 : 5053–64.

43. JahnsMT, VezonD, ChambonA, PereiraL, FalqueM, et al. (2014) Crossover localisation is regulated by the neddylation posttranslational regulatory pathway. PLoS Biol 12: e1001930 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001930

44. MundtKE (2002) Deletion Mutants in COP9/Signalosome Subunits in Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe Display Distinct Phenotypes. Mol Biol Cell 13 : 493–502 doi:10.1091/mbc.01-10-0521

45. StuttmannJ, ParkerJE, NoëlLD (2009) Novel aspects of COP9 signalosome functions revealed through analysis of hypomorphic csn mutants. Plant Signal Behav 4 : 896–898.