-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Histone Deacetylase Adjusts Transcription Kinetics at Coding Sequences during Morphogenesis

Despite their classical role as transcriptional repressors, several histone deacetylases, including the baker's yeast Set3/Hos2 complex (Set3C), facilitate gene expression. In the dimorphic human pathogen Candida albicans, the homologue of the Set3C inhibits the yeast-to-filament transition, but the precise molecular details of this function have remained elusive. Here, we use a combination of ChIP–Seq and RNA–Seq to show that the Set3C acts as a transcriptional co-factor of metabolic and morphogenesis-related genes in C. albicans. Binding of the Set3C correlates with gene expression during fungal morphogenesis; yet, surprisingly, deletion of SET3 leaves the steady-state expression level of most genes unchanged, both during exponential yeast-phase growth and during the yeast-filament transition. Fine temporal resolution of transcription in cells undergoing this transition revealed that the Set3C modulates transient expression changes of key morphogenesis-related genes. These include a transcription factor cluster comprising of NRG1, EFG1, BRG1, and TEC1, which form a regulatory circuit controlling hyphal differentiation. Set3C appears to restrict the factors by modulating their transcription kinetics, and the hyperfilamentous phenotype of SET3-deficient cells can be reverted by mutating the circuit factors. These results indicate that the chromatin status at coding regions represents a dynamic platform influencing transcription kinetics. Moreover, we suggest that transcription at the coding sequence can be transiently decoupled from potentially conflicting promoter information in dynamic environments.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003118

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003118Summary

Despite their classical role as transcriptional repressors, several histone deacetylases, including the baker's yeast Set3/Hos2 complex (Set3C), facilitate gene expression. In the dimorphic human pathogen Candida albicans, the homologue of the Set3C inhibits the yeast-to-filament transition, but the precise molecular details of this function have remained elusive. Here, we use a combination of ChIP–Seq and RNA–Seq to show that the Set3C acts as a transcriptional co-factor of metabolic and morphogenesis-related genes in C. albicans. Binding of the Set3C correlates with gene expression during fungal morphogenesis; yet, surprisingly, deletion of SET3 leaves the steady-state expression level of most genes unchanged, both during exponential yeast-phase growth and during the yeast-filament transition. Fine temporal resolution of transcription in cells undergoing this transition revealed that the Set3C modulates transient expression changes of key morphogenesis-related genes. These include a transcription factor cluster comprising of NRG1, EFG1, BRG1, and TEC1, which form a regulatory circuit controlling hyphal differentiation. Set3C appears to restrict the factors by modulating their transcription kinetics, and the hyperfilamentous phenotype of SET3-deficient cells can be reverted by mutating the circuit factors. These results indicate that the chromatin status at coding regions represents a dynamic platform influencing transcription kinetics. Moreover, we suggest that transcription at the coding sequence can be transiently decoupled from potentially conflicting promoter information in dynamic environments.

Introduction

Cells with identical genomes can adopt various phenotypes, which is a central feature during differentiation of multicellular organisms. During differentiation, the outside stimuli and the cellular machineries that process them are thought to determine the resulting cell types. Often, both the original and the resulting cell types are stable and display defined morphologies and gene expression programs. Understanding how such transitions between two stable cellular states are controlled and achieved on the molecular level is of central importance for understanding development and the relationship of organisms with their environment.

Unicellular species such as simple fungi can also undergo differentiation. For instance, pleiomorphic fungi, such as the opportunistic human pathogen Candida albicans display diverse morphologies ranging from unicellular yeast-like, to multicellular pseudohyphal, and hyphal structures [1], [2]. The ability to undergo reversible transitions between the distinct morphologies is a key virulence factor of C. albicans, shared by many other pathogenic fungi of even distantly related taxa such as Histoplasma and Cryptococcus [2], [3]. Consequently, blocking fungal morphogenesis represents a plausible antifungal therapeutic strategy [4].

Hyphal differentiation of C. albicans is responsive to environmental and host stimuli and is controlled by several signal transduction cascades and over thirty transcriptional regulators [5], [6], [7], [8]. Nevertheless, how the individual factors interact and how they integrate information from upstream signaling cascades is poorly understood. Recently, several studies have implicated chromatin and chromatin-modifying enzymes in the signal integration process. For example, the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and the Hda1 histone deacetylase (HDAC) mediate dynamic acetylation and deacetylation of histones at promoter regions of hypha-specific genes, and their proper function is required for the establishment of a normal filamentation expression program [9]. In yeast-phase cells, hyphal-specific genes are repressed by the transcription factor Nrg1 [10], [11]. During hyphal initiation, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling drives eviction of Nrg1 from its target promoters, where Hda1 is recruited by another transcription factor, Brg1 [10], [12]. Hda1 activity subsequently results in the eviction of NuA4 from the target promoters, which prevents Nrg1 rebinding [10]. In this model, promoter chromatin is perceived as a platform for temporally regulated transcription changes in morphogenesis. Consistent with this notion, several other chromatin modifier mutants, including the histone methyltransferase Set1 [13], the HAT Rtt109 [14], and the Set3 HDAC complex [15] display morphogenesis-related phenotypes.

The Set3 Complex (Set3C) was first identified as a repressor of sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and sequence homology suggests that it is evolutionarily conserved from fungi to mammals [16]. The catalytic subunit Hos2 was the first identified non-canonical HDAC required for gene activity [17]. In S. cerevisiae, the Set3C occupies the coding sequence of highly transcribed genes and is required for full expression of the galactose-inducible gene cluster [17]. Deacetylation of nucleosomes within the coding regions is thought to reset chromatin to a permissive state facilitating repeated cycles of transcription [17], [18]. Homologues of the Set3C in other fungal species have been implicated in the regulation of morphogenesis and virulence [19], [20]. We have recently shown that the C. albicans Set3C acts as a repressor of hyphal differentiation and its function requires functional cAMP/PKA signaling [15].

In this study, we set out to identify the molecular mechanism through which the C. albicans Set3C controls morphogenesis. First, we used a combination of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-Seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to define the genome-wide regulatory target genes of the Set3C in yeast and hyphal cells. We found that similar to its S. cerevisiae homologue, the CaSet3C exclusively decorates coding regions and is associated with high transcriptional activity. However, during transient hyphal-inducing conditions, the Set3C delays the establishment of the hyphal-specific gene program by modulating the transcript levels of four phase-specific transcription factors (BRG1, TEC1, NRG1, EFG1), suggesting that the Set3C can act both as a transcriptional activator and repressor. We also demonstrate that these four factors form a core transcriptional circuit underlying morphogenesis, whose output is restricted by the Set3C. The results provide comprehensive insights into the mechanisms whereby the chromatin layer of regulation superimposes on a core transcriptional factor circuit that controls cellular morphogenesis in C. albicans and possibly in other fungal pathogens.

Results

The C. albicans Set3C is a coding sequence histone deacetylase

In S. cerevisiae, the Set3C is composed of seven different subunits, which show sequence conservation in C. albicans and mammals [15], [16]. In S. cerevisiae, four of the subunits form a core complex (Set3, Hos2, Snt1, Sif2) and are required for structural integrity, while three additional subunits are peripheral (Hst1, Cpr1, Hos4) [16]. To enable biochemical investigation of the CaSet3C, we constructed a series of C. albicans strains carrying epitope-tagged alleles of the Set3 and Hos2 subunits. C. albicans is diploid, thus the second alleles in these strains were deleted. Since deletion of the Set3C causes hyperfilamentation [15], phenotypic analysis ensured that the tagged alleles were functional (Figure S1A). To probe the conservation of the complex architecture, we immunoprecipitated Set3 and Hos2 from whole cell extracts, and identified their interaction partners by mass spectrometry. Both subunits co-purified with the homologues of all S. cerevisiae core complex subunits (Set3, Hos2, Snt1, Sif2) (Figure S1B), indicating that the core complex is conserved in C. albicans (Figure 1A). In addition, we verified the Set3-Hos2 interaction by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting (Figure 1B) and confirmed nuclear localization of the complex with a Hos2-GFP construct (Figure S1C).

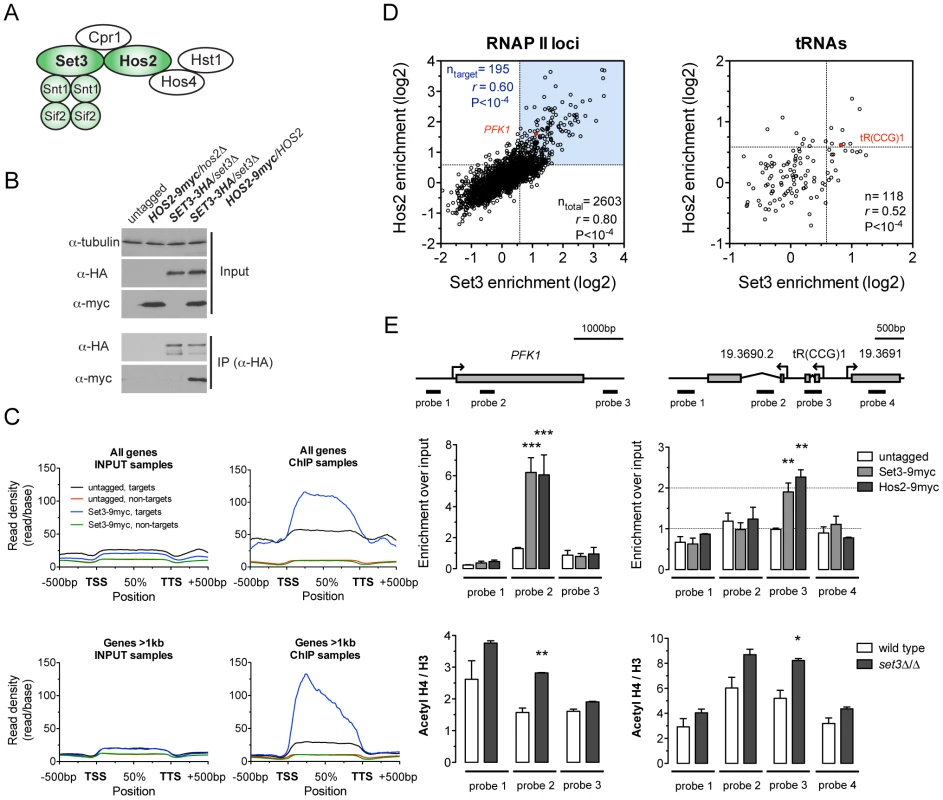

Fig. 1. The C. albicans Set3C is a coding sequence histone deacetylase.

(A) Architecture of the S. cerevisiae Set3C. The subunits among which physical interaction was confirmed in C. albicans are colored green (see Figure S1B). (B) Physical interaction of Set3 and Hos2. Set3-3HA was immunoprecipitated from whole cell extracts and the interaction was probed by immunoblot detection of a Hos2-9myc allele. (C) Read density profiles of one replicate of a Set3-9myc and an untagged control ChIP-Seq experiment. Genes were divided into binding targets (“targets”) and non-targets (see Materials and Methods). Transcription start site (TSS) denotes the start codon and Transcription termination site (TTS) denotes the stop codon. The read density values between the TSS and TTS were calculated to a percentage scale, and 500 bases upstream of the TSS and downstream of the TTS were included. On the bottom panel only genes with a coding region longer than 1 kilobase were included. (D) Definition of CaSet3C refined target gene set. Each dot corresponds to one ORF. Binding targets of RNAPII transcribed genes are defined as having an at least 2-fold enrichment on one axis and an at least 1.5-fold on the other axis (blue box). Target tRNA loci are defined as having an at least 1.5-fold enrichment on both axes. The complete dataset is found in Tables S4 and S5. “r” denotes a Pearson's correlation coefficient. (E) The Set3C functions as histone deacetylase in vivo. Top panel: validation of Set3 and Hos2 binding using the indicated probes around the PFK1 and tR(CCG)1 loci by qPCR. Values are normalized to a fragment of the ADE2 locus. Bottom panel: ChIP experiments were performed with antibodies against acetylated histone H4 and the C-terminus of histone H3. The qPCR values at the probe positions were normalized to a fragment of the telomere of Chromosome 7. The ratio of the signal of the acetylated H4 ChIP and H3 ChIP is shown on the y-axis. Data are shown as mean+SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-test relative to the control values. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. To obtain a genome-wide binding profile of the Set3C and to determine its regulatory targets, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-Seq) of Set3 and Hos2 in exponentially growing yeast-phase cultures. We first identified binding peaks using Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) [21], and found that 90% of all peak summits and around 85% of positions within peak regions fall within annotated coding regions (Figure S3A). Read density profiles averaged across all genes (meta-gene analyses) confirmed the strict localization of binding to coding regions (Figure 1C), and suggested that binding of Set3 and Hos2 to each gene across conditions could be assessed quantitatively by read-coverage of the coding regions (in reads-per-kilobase-per-million-reads [RPKM]) similar to RNA-Seq analyses; see Materials and Methods). Set3 and Hos2 enrichments showed a strong correlation genome-wide both for RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII)-transcribed genes (r = 0.80, Pearson's correlation) and RNAPIII-transcribed tRNA loci (r = 0.52, Pearson's correlation), arguing that both subunits co-localize on the chromosome (Figure 1D).

To test whether the Set3C indeed functions as a histone deacetylase in vivo, we performed ChIP experiments of acetylated histone H4. The ratio of acetylated H4 to total histone H3 was increased in a set3Δ/Δ strain when compared to wild type at the Set3C-bound positions (Figure 1E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the C. albicans Set3C has histone deacetylase activity and localizes to coding regions of its target genes and tRNA loci.

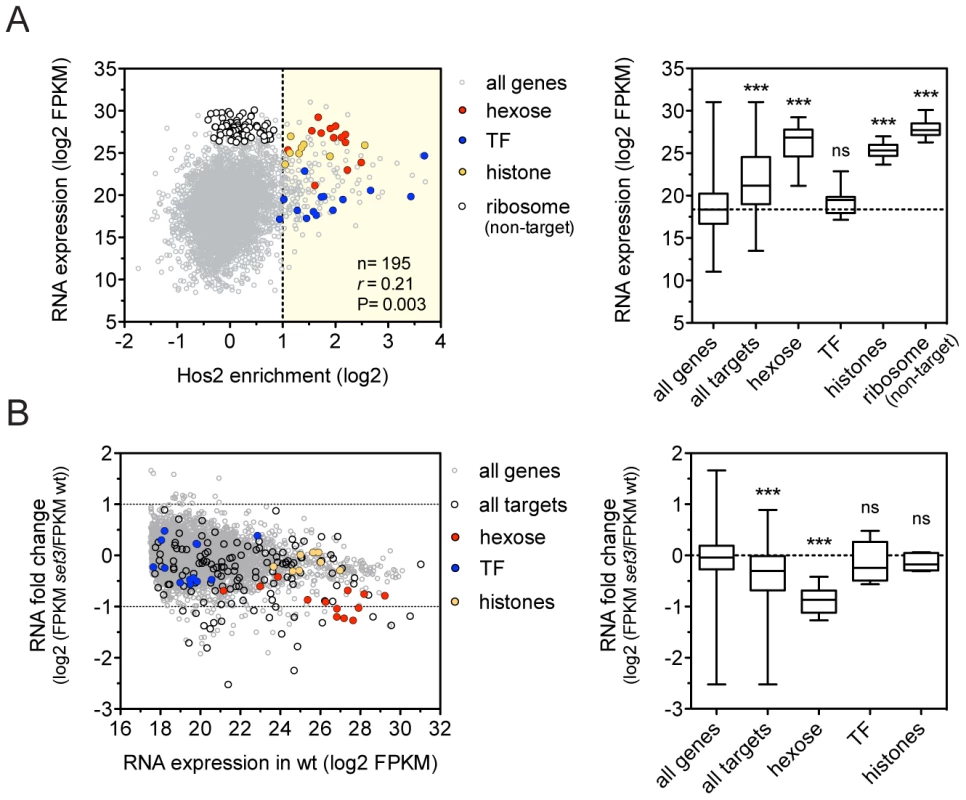

The Set3C decorates highly transcribed genes

To dissect how the Set3C regulates gene transcription, we performed RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) of exponentially growing yeast-phase cultures. We found that C. albicans Set3C target genes were on average 8.7-fold more highly expressed than all genes (Figure 2A), and that binding correlated with RNA expression, as described for the S. cerevisiae homologue (Figure S4A) [17]. In particular, hexose catabolism genes and nucleosomal histone genes (both enriched among Set3C targets; P = 1.3×10−10, P = 8×10−8, respectively) are both highly occupied and expressed (Figure 2A). This implies that Set3C might be involved in enhancing gene expression of its target genes. However, surprisingly, when we performed RNA-Seq of a SET3-deletion mutant, the expression levels of only few target genes were affected, including the hexose catabolic genes (Figure 2B, Figure S4B). In contrast, histone genes and transcription factors, another functional category enriched among the targets (P = 2×10−3) remained unaffected. In wild type cells, acetylation level of histone H4 at the coding sequences of selected Set3C-targets correlated with RNA expression (r = 0.88, Pearson's correlation, Figure S4D). Moreover, increased acetylation of histone H4 was detectable at almost all tested loci in set3Δ/Δ cells (Figure S4C). These data argue that the occupancy of Set3C is linked to active transcription, but the presence of Set3C at transcribed gene bodies influences the steady-state transcript levels of only a small subset of targets.

Fig. 2. The Set3C decorates highly transcribed genes.

(A) Correlation of Set binding and RNA expression for the target gene set (defined on Figure 1D). Each dot corresponds to one gene. The distribution of expression values of the genes belonging to each functional category is shown on the right panel. “r” denotes a Pearson's correlation coefficient. TF stands for the transcription factor cluster (see text). Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney U-test relative to the “all genes” set. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns: not significant. (B) Transcript profile of set3Δ/Δ cells by RNA-Seq. The fold change in RNA expression between set3Δ/Δ and wild type cells at each gene is plotted against the expression level of the gene in wild type cells. The direct binding targets and their functional groups are highlighted. The distribution of fold changes of the genes belonging to each functional category is shown on the right panel. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney U-test relative to the “all genes” set. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns: not significant. Set3C recruitment predicts induction, while depletion predicts repression

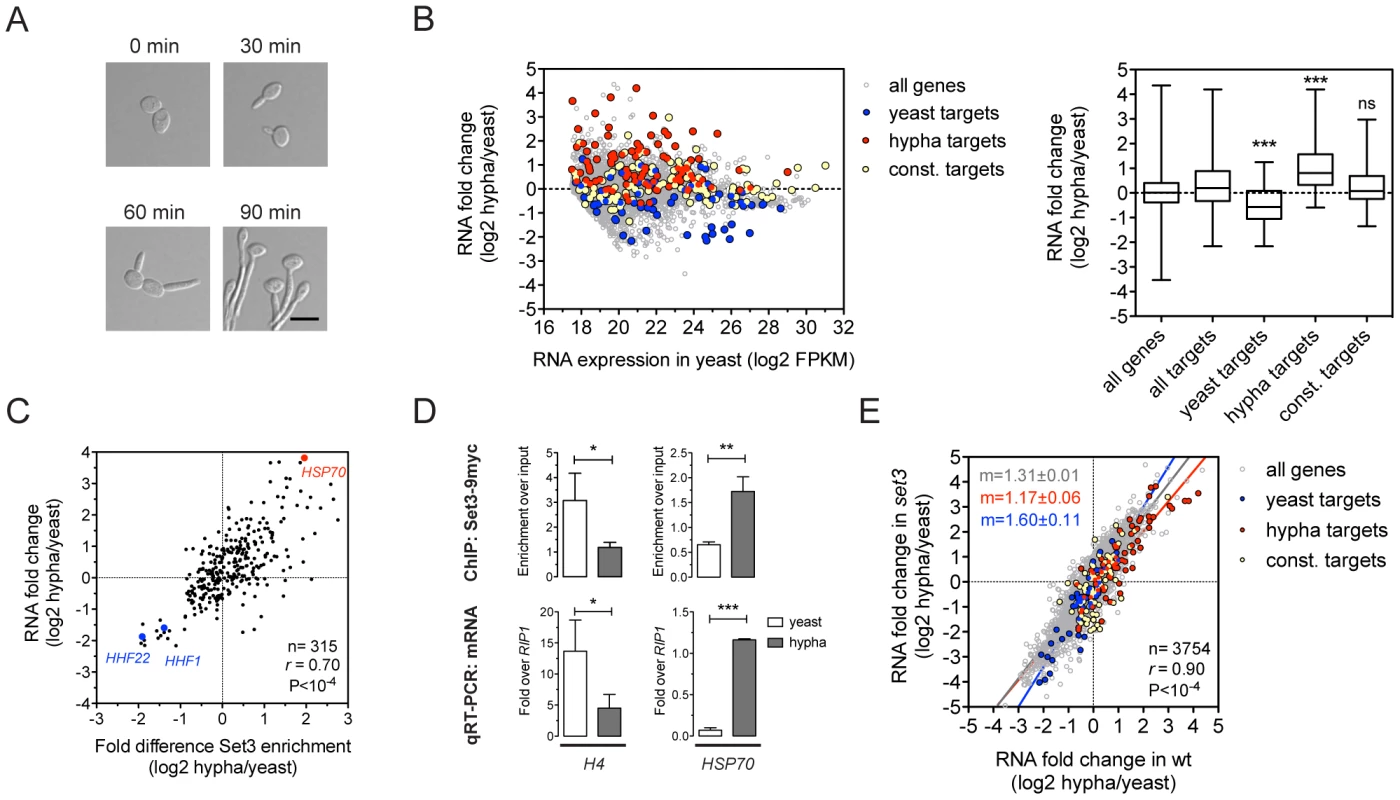

The yeast-to-hypha transition in C. albicans, which is repressed by the Set3C [15], involves transcriptional changes that affect around 600 genes, corresponding to roughly 10% of the genome [11], [22]. To further dissect how the Set3C represses this transition, we indentified the binding targets of the Set3C in cells exposed to filament-inducing conditions (Figure 3A). In total, we detected 237 Set3C targets in hyphae, after a 30 minute induction. The ratio of the hypha/yeast ChIP-Seq values was used to classify a hypha-specific target gene set (127), a yeast-specific target set (85) or genes constitutively bound (110) (Table S5). We also performed RNA-Seq during filament formation and found that hypha-specific Set3C targets were on average induced whereas yeast-specific target genes were repressed upon filament-induction (Figure 3B). In fact, the differential RNA expression values and differential ChIP enrichment signals showed a strong correlation both for Set3 (r = 0.69, Pearson's correlation) and Hos2 (r = 0.8, Pearson's correlation) (Figure 3C, 3D; data not shown). However, when set3Δ/Δ cells were induced to form hyphae, their transcript induction profile was virtually identical to that of wild type cells (r = 0.9, Pearson's correlation, Figure 3E). These results clearly demonstrate that the Set3C is recruited to induced genes while it is depleted from repressed genes upon hyphal induction. Notably, set3Δ/Δ cells are still able to efficiently execute initiation of the hypha-specific transcriptional program.

Fig. 3. Set3C recruitment predicts induction and depletion predicts repression.

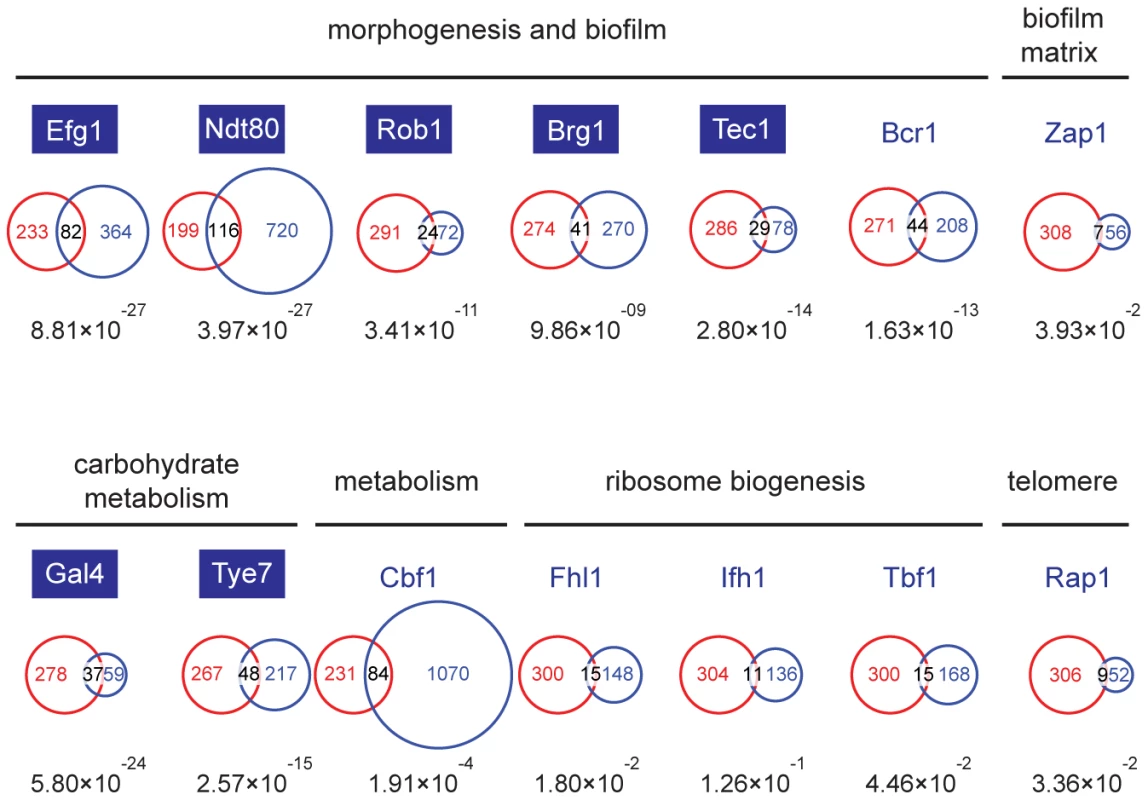

(A) Microscopic images of cells undergoing yeast-to-hypha differentiation. The cells at each time point do not correspond to the cells at the other time points. Scale bar corresponds to 5 µm. (B) Transcript landscape of hyphal cells 30 minutes after induction. The fold change in RNA expression between hyphal and yeast cultures at each gene is plotted against the expression level of the gene in wild type yeast cells measured by RNA-Seq. Each dot represents one gene. Set3C binding targets were defined by Set3C ChIP-Seq experiments (see Materials and Methods). The Set3C target genes are divided into yeast-specific, hypha-specific and constitutively bound subgroups. The distribution of RNA fold changes of the genes belonging to each category is shown on the right panel. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney U-test relative to the “all targets” set. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns: not significant. (C) Correlation of RNA fold change and differential ChIP enrichment signals. Each dot corresponds to one gene, and only the genes defined as Set3C binding targets in at least one phase are shown. “r” denotes a Pearson's correlation coefficient. (D) qPCR verification of the correlation on (C). Histone H4 has two loci in C. albicans (HHF1 and HHF22), and the primers used in the qPCR bind alleles of both. Data are shown as mean+SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (E) Comparison of the gene induction profiles of wild type and set3Δ/Δ cells undergoing hyphal differentiation. Fold change between the hyphal and yeast phases for the two genotypes are plotted on the two axes. Each dot corresponds to one gene. The categories of Set3C binding targets are defined as on (B). “r” denotes a Pearson's correlation coefficient, and “m” denotes the slope of the linear regression. The Set3C is a co-factor of glycolysis and morphogenesis regulators

Though the Set3C appears to be selectively recruited to a subset of transcribed genes, the differences in steady-state transcription and gene induction patterns in set3Δ/Δ cells are most surprisingly only minimal, and cannot explain why set3Δ/Δ cells are hyperfilamentous. To identify such potentially misregulated loci, we decided to identify which transcription factor(s) are responsible for Set3C recruitment, and collected the target lists of all transcription factors (TFs) whose genome-wide binding has been analyzed in C. albicans. These candidate TFs have been implicated in several cellular processes, including morphogenesis and biofilm formation [23], biofilm matrix regulation [24], carbohydrate metabolism [25], ribosome biogenesis [26], telomere control [26] and metabolic pathways [26]. Interestingly, the P-values of the overlaps showed an around 10 order of magnitude difference for TFs involved in morphogenesis (Efg1, Ndt80, Rob1, Brg1, Tec1) and carbohydrate metabolism (Gal4, Tye7) compared to other TFs (Figure 4). The fact that glycolytic genes were enriched in the GO-term analysis (see above) is in agreement with the finding that the Set3C target list shows a significant overlap with the targetome of Gal4 and Tye7, the major activators of the glycolytic gene cluster [25]. To our surprise, we also found that TFs whose target set showed a significant overlap with the Set3C set are themselves Set3C targets (blue boxes, Figure 4). Taken together, these results indicate that Set3C is a transcriptional co-factor of morphogenesis and glycolysis regulators. The fact that the regulators themselves are Set3C targets suggests that misregulation of rather the TF genes and not their targets could be the cause of the hyperfilamentous phenotype displayed by set3Δ/Δ cells.

Fig. 4. The Set3C is a co-factor of glycolysis and morphogenesis regulators.

Statistical analysis of the overlaps of the target genes of selected transcription factors with the target gene set of Set3C in the individual phases. The TF target sets are shown in blue, the Set3C target sets in red, and the TFs are grouped according to the functions they are implicated in. The target sets of the TFs were imported from the following reports: Efg1, Ndt80, Rob1, Brg1, Tec1 and Bcr1 from [23], Zap1 from [24], Gal4 and Tye7 from [25], Cbf1, Fhl1, Ifh1, Tbf1 and Rap1 from [26]. The area of the circles and overlaps are proportional to the number of genes they consist of. For each overlap the P-value of hypergeometric testing is shown. Transcription factors that are themselves binding targets of Set3C in at least one morphological phase are placed in blue boxes. The Set3C regulates morphogenesis through a transcription factor cluster

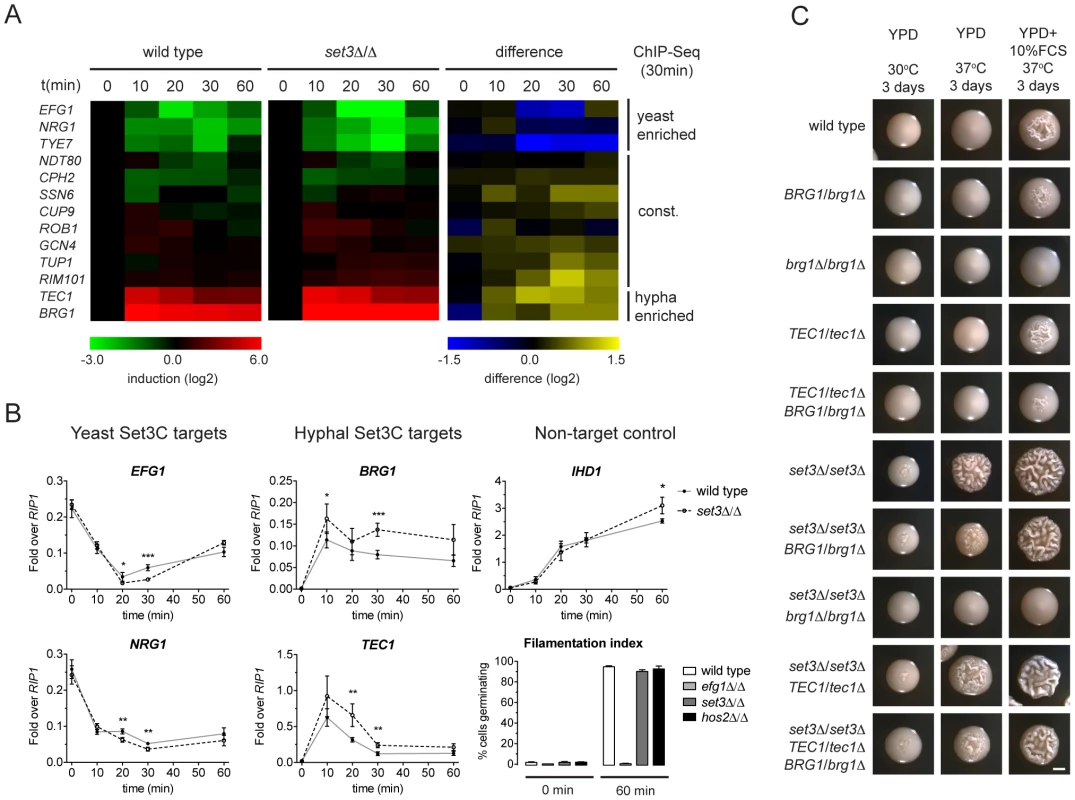

While morphogenesis regulators are major Set3C targets, and their target sets show significant overlap with the Set3C targetome, steady-state transcript levels of TFs were unaltered in set3Δ/Δ yeast phase cells (Figure 2B). Thus, we hypothesized that if altered transcription of TFs is responsible for the hyperfilamentous phenotype of set3Δ/Δ cells, this effect could be transient. Consequently, we analyzed the transcript level changes of the Set3C-target TFs at a high kinetic resolution around the induction stimulus. We found that the transcript levels of EFG1, NRG1, TYE7, which were identified as hyphal-enriched Set3C targets, undergo a rapid decrease following hyphal induction. By contrast, a rapid 50–100-fold induction of transcripts of the hyphal-specific targets BRG1 and TEC1 were visible after only 10 minutes (Figure 5A). The TFs bound constitutively by the Set3C did not show significant transcript changes around the induction point. This pattern was qualitatively identical in differentiating set3Δ/Δ cells. However, a 1.5–2-fold quantitative difference was observed between wild type and set3Δ/Δ cells at several time points that mostly affected the phase-specific TFs (Figure 5A, 5B). For instance, BRG1 transcript level was about 1.5-fold higher in set3Δ/Δ cells at all time points following induction, and TEC1 transcript level was 2-fold higher in set3Δ/Δ cells at 20 and 30 minutes post induction. On the other hand, EFG1 and NRG1 transcript levels showed an approximate 1.5–2-fold decrease in set3Δ/Δ cells at 20 and 30 minutes, respectively (Figure 5A, 5B). This suggested that the hypha-specific factors reach higher transcript levels in set3Δ/Δ cells, while the yeast-specific factors are repressed more upon hyphal differentiation. This effect was not a result of more cells responding to serum in the set3Δ/Δ culture, as the non-target IHD1 gene showed a quantitatively identical induction pattern, and the number of filamenting cells was scored above 90% percent after a 60 minute induction in both genotypes (Figure 5B; additional supporting qRT-PCR data in Figure S5).

Fig. 5. The Set3C modulates morphogenesis through a TF cluster.

(A) qRT-PCR quantification of the indicated transcripts in wild type and set3Δ/Δ yeast cells induced to differentiate into hyphae 10, 20, 30 and 60 minutes after induction. The transcript levels are normalized against RIP1 expression and the level of the respective gene in yeast cells (0 min). The right panel shows the quantitative difference between the values in the two genotypes at each individual time point. Average values of four independent experiments are shown. (B) Transcript levels of BRG1, TEC1, NRG1 and EFG1 in differentiating wild type and set3Δ/Δ yeast cells as on (A) quantified by qRT-PCR. IHD1 is hyphal-induced non-Set3C-target control gene. In the bottom right panel the percentage of cells germinating at the starting cultures and 60 minutes post induction is shown as a control. Data are shown as mean+SD of four independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (C) Removal of one BRG1 allele reverts hyperfilamentation of set3Δ/Δ cells under intermediate inducing conditions. Shown are photographs of single colonies. YPD at 30°C supports yeast-phase growth, YPD+FCS at 37°C supports hyphal growth, YPD at 37°C represents “intermediate” conditions. Scale bar corresponds to 2 mm. If the transient transcript level differences of the phase specific TFs cause the hyperfilamentous phenotype of set3Δ/Δ cells, then manipulation of the levels of the TFs should be epistatic to the lack of SET3. Indeed, we found that removal of one BRG1 allele almost completely reverted the hyperfilamentous phenotype of set3Δ/Δ cells under intermediate conditions, while deletion of one TEC1 allele did not (Figure 5C), which is probably explained by the facts that TEC1 expression shows a burst upon induction as opposed to BRG1 that stays stably high. These data demonstrate that the Set3C adjusts transient expression of phase-specific morphogenesis regulators during hyphal differentiation, and that genetic interference with the BRG1 regulator is sufficient to partially revert Set3C-deficiency.

The four phase-specific Set3C-target TFs form a core transcriptional circuit

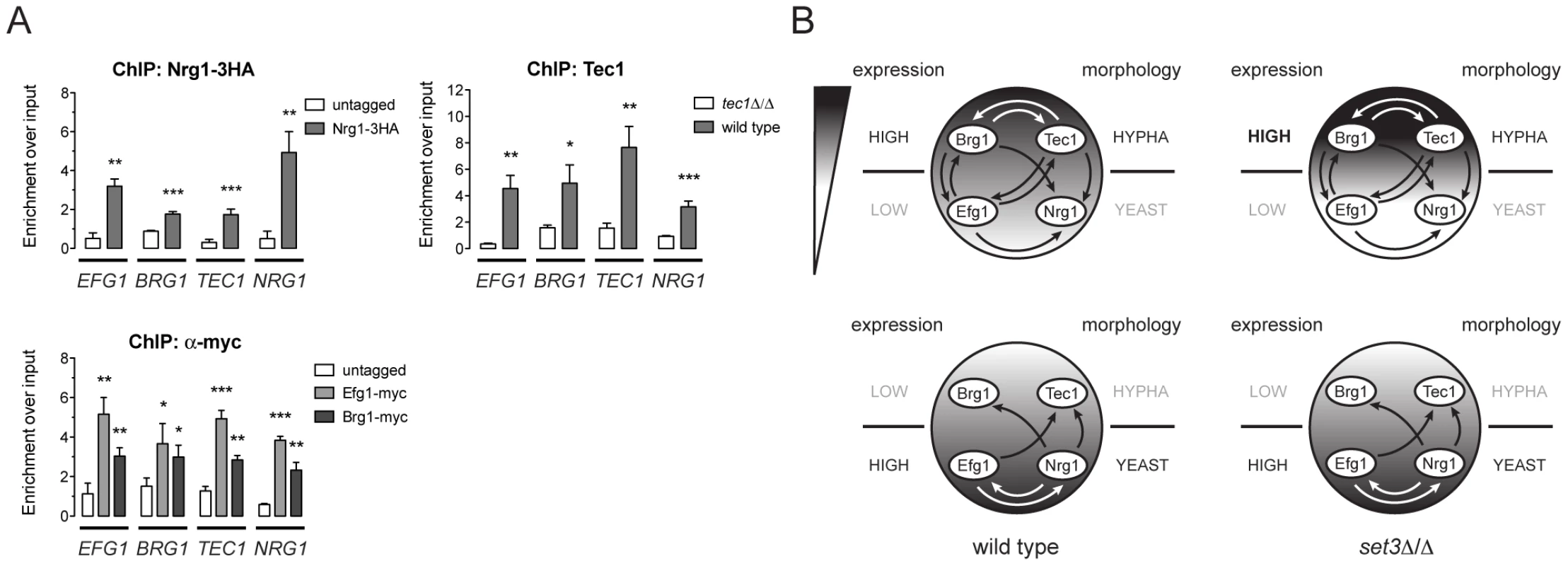

Biofilm formation in C. albicans is controlled by a transcriptional circuit comprising of six core regulators, including BCR1, BRG1, NDT80, EFG1, ROB1 and TEC1 [23]. Strikingly, five out of the six factors (all except BCR1) are Set3C targets, and three of the factors (BRG1, EFG1 and TEC1) showed altered transcription kinetics in set3Δ/Δ cells (Figure 5A). We therefore tested if the four phase-specific regulators that display Set3C-dependent transcription kinetics (BRG1, EFG1, TEC1 and NRG1) also form a regulatory circuit. Remarkably, ChIP experiments revealed that Nrg1 bound its own promoter and the promoters of the other three TFs in yeast-phase cells (Figure 6A). Tec1, Brg1 and Efg1 also bound the promoter regions of all four factors in hyphae (Figure 6A). Together with a recent genome-wide binding map of Efg1 in yeast phase [27], these data allow for the reconstruction of a partial map of the transcriptional circuit that underlies hyphal differentiation in C. albicans (Figure 6B).

Fig. 6. Four phase-specific Set3C-target TFs form a core circuit.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of Nrg1, Tec1, Efg1 and Brg1 binding at the EFG1, BRG1, TEC1 and NRG1 promoters. ChIP experiments were performed in yeast phase for Nrg1 and hyphal phase for Tec1, Efg1 and Brg1. Data are shown as mean+SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (B) Simplified model of the transcription circuit overlayed with a chromatin pathway to regulate C. albicans morphogenesis. The big circle represents the transcript profiles of the four regulators with the indicated scaling. The arrows representing regulatory information are derived from the ChIP experiments at (A). The arrows of Efg1 in the yeast phase are taken from the genome-wide binding data in [27]. The arrows representing autoregulation of each four regulators are omitted for simplicity. Note that in set3Δ/Δ cells, the architecture of the TF-circuit remains intact, yet the temporary differences in the regulator mRNA levels are represented by the differences in the grayscale. Discussion

In this study, we set out to dissect how the conserved Set3C histone deacetylase complex regulates hyphal differentiation in the human fungal pathogen C. albicans. Our data not only provide mechanistic and evolutionary insights into how chromatin deacetylation at the coding sequences regulates gene expression, but also allow for the characterization of the transcriptional circuitries underlying fungal morphogenesis. Remarkably, our data show that the activity of the transcriptional layer of gene regulation is fine-tuned by a second layer requiring chromatin modification.

A transcription factor-chromatin modifier network controls C. albicans morphogenesis

To date, over a hundred genes have been implicated in C. albicans morphogenesis, including numerous conserved signaling cascades and transcription factors [6], [7], [8], [28]. However, a comprehensive understanding of how the underlying genetic circuit is organized and how it integrates outside stimuli is still lacking. Our data has led to surprising insights into the architecture of the hyphal regulatory circuit, whose simplified model is shown in Figure 6B. In this model, a core circuit is formed by four TFs, two of which are enriched in the yeast phase (NRG1 and EFG1) and two are enriched in hyphae (TEC1 and BRG1). The four factors form an interwoven network, whereby all four factors regulate themselves, as well as the other three factors. For practical reasons, we consider here the yeast-specific phase of the circuit as the ground state. In yeast cells, Nrg1 represses hyphal-specific genes, and cAMP/PKA signaling-dependent removal of Nrg1 is required for the induction of hyphal genes [10], [11], [12]. The relief of Nrg1 repression enables expression of hyphal-specific genes such as the TFs Brg1 and Tec1, which once expressed, repress the promoters of the yeast-specific regulators and reinforce their own expression (Figure 6A). This “excited” state of the circuit is subsequently responsible for the establishment of a normal hyphal transcription program. Indeed, all four TF genes are strong binding targets of the Set3C in their respective phases. In set3Δ/Δ cells, the circuit remains intact, but shows a “hyper-excited” state shortly after hyphal induction, that is reflected in the transcript levels of all four regulators (Figure 5, Figure 6B; Table S5). (It is, however, possible that the early surplus of BRG1 is at least partially accountable for the transcriptional effect at the other three TF loci.) Further evidence for the “hyper-excited” state includes the elevated expression of verified Brg1 target transcripts such as UME6 and HGC1 (Figure S5). This model predicts that in set3Δ/Δ cells the circuit responds to weaker hypha-inducing stimuli than in wild type cells, which explains why set3Δ/Δ cells are hyperfilamentous under “intermediate” conditions (Figure S1, Figure 5C; [15]). The model receives further support by the finding that removal of one BRG1 allele partially reverts the phenotype of set3Δ/Δ cells (Figure 5C). Thus, though many additional TFs are implicated in morphogenesis, we believe this simple circuit architecture is consistent with several key features of the differentiation process.

Recently, a similar, small transcription factor network composed of six core TFs was identified as the master network controlling biofilm formation of C. albicans [23]. Biofilms are formed on solid surfaces and indwelling medical devices by a population of diverse cell morphologies (including yeast, pseudohyphal and hyphal forms) that are embedded in an extracellular matrix. Remarkably, five out of the six biofilm regulators are Set3C targets (TEC1, BRG1, EFG1, NDT80 and ROB1), and three factors are found in the hyphal regulatory circuit (TEC1, BRG1 and EFG1). Hence, if the Set3C restricts the excitation state of the hyphal regulatory network, and there exists at least a partial overlap between the two regulatory circuits, the Set3C may also affect the output of the biofilm regulatory circuit and thus modulate biofilm formation. Strikingly, set3Δ/Δ cells produce a strong “rubbery” biofilm with visibly stronger mechanical properties when compared to wild type cells (Figure S6, Nobile and Johnson, unpublished data). These results strongly suggest that a kinetic control of transcriptional circuit components by the Set3C modulates biofilm formation, and likely constitutes a conserved regulatory mechanism underlying morphogenetic processes in C. albicans.

Mechanistic and evolutionary aspects of the function of the Set3C

In S. cerevisiae, the Set3C binds to gene bodies where it deacetylates various residues of histones H3 and H4 [17]. The occupancy of the complex correlates with expression, and in set3Δ/Δ cells, galactose metabolic genes are turned on with a slower kinetics when compared to wild type after galactose induction, which suggests that the complex is required for gene induction [17]. In addition, Hos2, the catalytic subunit of the SetC3 binds at a few tRNA loci where it is necessary for efficient integration of Ty1 retrotransposons [29]. The C. albicans Set3C also decorates coding regions and tRNA loci, and its presence correlates with transcriptional activity, supporting the notion of conservation of Set3C localization being linked to active transcription. However, the genome-wide association analysis does not reveal how the recruitment of the complex affects transcription itself. In S. cerevisiae, the genetic removal of Set3 has only a marginal effect on genome-wide transcription [30]. Recently, a systematic study of chromatin-modifier mutants in S. cerevisiae revealed that several enzymes modulate the induction kinetics of their target genes rather than steady-state transcript levels [31]. Similarly, we detected transcript level differences at only 19% of the Set3C binding targets in set3Δ/Δ C. albicans cells. These genes mostly include the glycolytic genes that were all downregulated in the set3Δ/Δ mutant, arguing for a positive role of the Set3C in transcription (Figure 2), but the exact role of the Set3C is possibly determined by the context it is recruited. Thus, such a static view of the steady-state transcript levels is insufficient to predict precise function. Indeed, we detected 50% more BRG1 mRNA in set3Δ/Δ cells than in wild type cells already after 10 minutes of hyphal induction, which implies that the Set3C can also exert repressive functions. This is in agreement with an early report where set3Δ/Δ diploid S. cerevisiae cells experienced premature activation of meiotic genes upon induction of sporulation [16], and indicates that both the context and timing of histone modifications contribute to the net transcriptional output [32]. Since in set3Δ/Δ cells, the TF-cluster genes were either “hyper-induced” or “hyper-repressed” during transient hyphal induction (Figure 5B), and several other Set3C targets showed altered transcription kinetics (Figure S5), we propose that the complex is also part of a conserved mechanism that creates a transient “transcriptional memory” at coding regions to buffer fast promoter changes. The mechanistic basis of opposing functions (repression and activation) could be that dynamic histone (de)acetylation affects nucleosome density at coding regions, while nucleosomes carry other modifications that directly affect transcription [33]. Indeed, we observed a slightly reduced nucleosome density at several target loci in set3Δ/Δ cells (data not shown).

Why would the chromatin at coding regions be used as such a relay platform? A detailed resolution of the transcriptomic response to several stresses in S. cerevisiae recently revealed that histone deacetylation at stress-responsive promoters by Rpd3 is required for normal induction and repression kinetics [34]. In our view, the utilization of coding region chromatin to adjust transcription kinetics is advantageous when several outside stimuli transmit potentially conflicting information to target promoters. In such cases, a transient decoupling of transcription from promoter input may provide sufficient time to shape the proper response to the environment or even prevent overshooting responses. In the cases of transcriptional circuits, the time needed to establish the new circuit output may be used to “decide” if the morphological conversion is in fact favorable under the given circumstances. Indeed, such a “test the waters” strategy was recently hypothesized to underlie white-opaque switching, another morphological switching process of C. albicans [35].

One of the most intriguing questions that arise based on these results is how the Set3C is selectively recruited to the coding sequences of its target genes. Localization is in fact so exclusive to gene bodies, that genomic segments encoding long 5′ untranslated regions (UTR) are completely devoid of ChIP-Seq signal (Figure S3C). In S. cerevisiae, recruitment of the Set3C has been linked to the recognition of H3K4me2 which decorates mainly coding regions [18], but most surprisingly, we found that genome-wide localization the C. albicans Set3C does not depend on dimethylation of H3K4 (Figure S7). Notably, despite the fact that Set3C occupancy correlates with expression of the corresponding locus, not all highly transcribed genes, for instance ribosomal protein genes, are Set3C targets (Figure 2). To rule out that this is caused by differences in RNA stability of the gene clusters, we examined RNAPII density [36], and found a similar correlation of Set3C enrichment with RNAPII density as with RNA level genome-wide (data not shown). This indicates that though Set3C recruitment is linked to active transcription by RNAPII, the recruitment signal stems from sequence-specific binding of transcription factors at the gene promoters. Our preliminary experiments indeed suggest that the promoter of a Set3C target gene is sufficient to direct the complex to exogenous gene bodies (data not shown). Although further experiments are necessary to dissect the mechanistic basis of the transmission of the recruitment information, we believe the transcriptional regulators either alone or more likely, in combination may direct posttranslational modification(s) of RNAPII, that contribute to Set3C recruitment once the polymerase reaches the coding region. Indeed, the plethora of modifications of the RNAPII C-terminal domain (CTD) has been postulated to constitute a “CTD code”, whereby specific CTD modifications orchestrate the binding of protein factors that affect RNA processing, RNAPII termination or histone modifications [37], [38], [39]. Thus, it is tantalizing to speculate that the Set3C and its homologues could serve not only as erasers of histone acetylation but also as readers of CTD modifications.

Adaptation through phenotypic transitions in changing environments

During its coevolution with the human host, C. albicans had to adapt to various niches representing a wide spectrum of physical, chemical and immunological parameters. One of its adaptive strategies appears to be controlling phenotypic transitions through small, evolvable transcriptional circuits that are responsive to outside stimuli of broad amplitudes. Our model proposes that the switch between distinct circuit phases proceeds through an intermediate stage characterized by chromatin changes not just at promoters, but also at gene bodies. We postulate that such chromatin-overlayed transcriptional regulatory circuits underlie the morphological diversity of C. albicans, and most likely many other pleiomorphic fungal pathogens.

Author note

We wish to point out that during the revision of this work, a report was published, demonstrating that the Set3C modulates transcription kinetics in response to carbon source shifts in S. cerevisiae [40]. This work shows that the yeast Set3C HDAC acts as an active repressor. Notably, indirect regulatory functions of Set3C can lead to positive regulation of target genes through a mechanism involving repression of overlapping non-coding RNAs [40].

Materials and Methods

Media and growth conditions

C. albicans strains were routinely cultured in YPD (2% Bacto Peptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% Dextrose). For solid media 2% agar was added. Yeast phase cultures were propagated at 30°C. To obtain exponentially growing yeast cells, single colonies were grown in YPD at 30°C overnight, diluted the next day to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1, and incubated on a rotary shaker for exactly five hours after which cultures reached OD600 = 0.8±0.05. For hyphal induction the cultures were split, one aliquot was washed once with distilled water and resuspended in prewarmed (37°C) YPD+20% fetal calf serum (FCS) of an equal volume of the starting culture. Induced cells were shaken at 37°C for 30 minutes, which provides enough time to induce several hypha-specific transcripts and it is before the first nuclear division occurring around 60 minutes after induction (data not shown). Cultures were optionally snap-frozen in liquid N2 after washing steps and stored at −80°C.

Strain construction

The complete list of C. albicans strains, primers and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S1, 2 and S3, respectively. All strains were derived from SN152 [41]. The wild type (CAIF-100), SET3/set3Δ (DHCA401), set3Δ/Δ (DHCA402), HOS2/hos2Δ (DHCA405) and hos2Δ/Δ (DHCA406) strains were previously described [15], [42]. SET1, BRG1 and TEC1 alleles were deleted using the fusion PCR strategy with the C.d.ARG4 and NAT1 markers [15], [41]. NRG1 and SET3 alleles were deleted using the SAT1 flipping strategy [15], [43]. Epitope-tagging constructs were created using the fusion PCR strategy [44] with the “tag-marker” donor plasmids described in Table S3. The Efg1-myc (CJN1781), Brg1-myc (CJN1734) and tec1Δ/Δ (CJN2320) strains were previously described [23]. The construct for targeted replacement of NRG1 with GFP was also created by fusion PCR. Transformation was performed via electroporation as described [43]. Correct genomic integration was verified with PCR and immunoblotting (for epitope tags).

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

IP was performed essentially as described [18] with modifications. Exponentially growing cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with distilled water. For Set3-HA and Hos2-3HA IPs (Figure 1B and Figure S1B) cells were resuspended in 300 µl stringent lysis buffer (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 300 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT and protease inhibitors). After addition of around 200 µl glass beads (425–600 µm, Sigma), cells were lysed at 5 m/s for 45 seconds 5 times on a FastPrep instrument (MP Biomedicals). Samples were chilled on ice for five minutes between cycles. Tubes were then centrifuged at 14000 g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant (around 300 µl) was transferred to a fresh tube and diluted to 1 ml with stringent lysis buffer. Whole cell extracts were incubated at 4°C overnight with agarose beads covalently bound to the 3F10 clone anti-HA antibody (Roche) with the amount of beads previously titrated to the amount of antigen in the respective amounts of extracts. The next day beads were washed six times with stringent lysis buffer and bound complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE. For the Set3-3HA-histone co-IPs (Figure S7) the same protocol was followed, except that a mild lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors) was used throughout the whole procedure and beads were washed only four times after immunoprecipitation. The antibodies used in the Western blot detection included anti-HA (3F10, Roche), anti-myc (ab32, Abcam) anti-H3 (ab1791, Abcam), anti-H4 (ab10158, Abcam) and anti-tubulin (DM1A, Sigma).

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was isolated by the hot phenol method [44] after which RNA was further purified by the SV Total RNA isolation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For qPCR, 500 ng total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the AMV reverse transcription system (Promega), and the diluted first strand cDNA was directly used as template. For RNA-Seq, 5 µg total RNA was depleted of rRNAs using the RiboMinus kit (Invitrogen) and cDNA was synthesized and amplified with the SMARTer cDNA synthesis kit (Clonetech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. 5 µg cDNA was purified with phenol∶chloroform∶isoamylalcohol extraction (PCI), precipitated in 70% ethanol at −20°C overnight, washed once with 70% ethanol, dissolved in distilled water, and was used as a template for library preparation. RNA quality was controlled with the BioAnalyzer (Agilent) during the whole procedure.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was performed essentially as described [44] with several modifications. Cultures were crosslinked by the addition of formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% for 15 minutes at room temperature. Crosslinking was quenched by the addition of 125 mM glycine for 5 minutes. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and pellets were frozen in liquid N2. Pellets corresponding to 80 OD600 cells were resuspended in 480 µl ice-cold ChIP lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, protease inhibitors). After addition of around 500 µl glass beads (425–600 µm, Sigma), cells were broken at 6 m/s for 60 seconds 8 times on a FastPrep instrument (MP Biomedicals). Samples were cooled on ice for five minutes between cycles. The bottom of the tubes was punctured with a 273/4G needle and lysates were collected by centrifugation at 1500 g for 1 min at 4°C into a fresh tube. The lysates were diluted to 2.4 ml with ChIP lysis buffer. Aliquots of 300 µl were sonicated 15 times with 30s ON/30s OFF cycles at high setting on a Bioruptor (Diagenode). After sonication the aliquots were combined and centrifuged once at 14000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and used as input chromatin lysates. Set3-9myc and Hos2-9myc ChIPs were performed using EZ-View anti-myc coupled agarose beads (Sigma). After overnight incubation at 4°C washing and DNA purification was performed exactly as described [44]. For histone ChIPs (on Figure 1E, Figure S4C, Figure S7F) anti-acetyl H4 (06-598, Millipore), anti-H3 (ab1791, Abcam) and anti-H3K4me2 (07-030, Millipore) were used. Brg1-myc and Efg1-myc ChIP was performed with a commercial anti-myc antibody exactly as described [23]. Nrg1-3HA ChIP was performed with an anti-HA antibody (ab9110, Abcam). Tec1 ChIP was performed with a custom anti-Tec1 antibody [23]. After overnight incubation at 4°C, ProteinG-coupled Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were added for 2 h at 4°C, and subsequent washing and DNA purification steps were performed exactly as described [44]. The sonication settings typically resulted in fragments sizes mostly around 200–300 bp, which was controlled by agarose gelelectrophoresis of purified input samples. All ChIP experiments were carried out at least with three biological replicate cultures.

RNA–Sequencing (RNA–Seq) and analysis

Sequencing of fragmented cDNA was carried out on a HiSeq 2000 instrument (Illumina) at GATC Biotech AG (Konstanz, Germany). Three biological replicates of wild type and set3Δ/Δ cells in both yeast and hyphal phases were included. The resulting 51 base reads were mapped onto the Assembly 21 of the C. albicans genome containing only the coding sequences using TopHat with default parameters, and allowing only for uniquely mapping reads [45]. Fragment Per Kilobase in a Million mapped reads (FPKM) values were calculated with Cufflinks, including quartile normalization (removing top 25% of genes from the FPKM denominator) and bias correction [46]. The transcript coordinates were fixed as in the annotation of the coding sequence assembly. For transcriptome analyses on Figure 2B and Figure 3B and the right panel of Figure 2A, only genes with a mean coverage of at least five nucleotides per base were included. Mean coverage was calculated as an average of the three biological replicates for each genotype or phase. For the transcriptome analysis on Figure 3E the same mean coverage cutoff (>5 nt/base) was used, but only for the wild type yeast and hyphal RNA-Seq samples. The complete RNA-Seq dataset is found in Table S6.

ChIP–Sequencing (ChIP–Seq) and analysis

ChIP libraries were sequenced on a GAIIx platform (Illumina). Three biological replicates of the Set3-9myc ChIP in wild type and set1Δ/Δ backgrounds in yeast phase cells were sequenced, with two biological replicates of Set3-9myc ChIP and Hos2-9myc ChIP in hyphal phase cells and two biological replicates of Hos2-9myc ChIP in yeast phase cells. ChIP material of six biological replicates of the untagged control strain in the yeast phase was pooled prior to library preparation. One input sample of each genotype in each morphological phase was also sequenced. Samples were multiplexed with custom adapters. Reads (31–32 base) were mapped onto the chromosomal Assembly 21 of the C. albicans genome using Bowtie, allowing only for uniquely mapping reads [47] (Figure S2). Peak calling was performed by MACS with mfold = 2 and effective genome size = 14.324.316 bp parameters [21]. With a peak calling method such as MACS, detected peak coordinates rely on arbitrary thresholds and can vary even between replicate samples, and peak positions cannot be adjusted. Therefore, we developed a Read Per Kilobase in a Million mapped reads (RPKM) pipeline for quantifying ChIP-Seq enrichment within gene bodies. RPKM measures the enrichment of sequence reads within fixed chromosomal coordinates and is generally used to quantify RNA species in RNA-Seq experiments when the precise transcript coordinates are known [48]. The RPKM values of all open reading frames (ORFs) were calculated using their default chromosomal coordinates in ORF Assembly 21. Overlapping genes were removed from further analyses. Since tRNA genes are relatively short (80–120 bp), 20 bases up - and downstream of their chromosomal coordinates were added to define tRNA-cluster positions, which were used in the RPKM calculation. If two adjacent tRNA genes were closer than 20 bases, they were included in the same cluster. Overall, RPKM(ChIP)/RPKM(input) values correlated with the MACS fold enrichment parameter in the same sample (Figure S3B). Hence, RPKM is a suitable quantitative readout of our peak signals. Enriched genes were initially defined as having an RPKM(ChIP)/RPKM(input) ≥2 with both RPKM values ≥10 (“targets” on Figure 1C). Since a few ORFs showed minor enrichment in the untagged control ChIP-Seq sample (Figure 1C and Figure S2), the RPKM ChIP values were subsequently normalized against the RPKM ChIP values of the untagged control instead of the respective input samples. Further normalization against the input samples for the comparison of genotypes was not necessary, because RPKM values of all input samples showed a high pairwise correlation (r>0.9, Pearson's correlation, not shown). We defined the Set3C target set as an ORF having at least 2-fold Set3 or Hos2 enrichment and at least 1.5-fold enrichment of the other (blue box, Figure 1D), or a tRNA having at least 1.5-fold enrichment of both (Figure 1D). For the genome-wide enrichment analyses on Figure 1D, Figure 3C, and Figure S7 only genes with an average RPKM≥5 in both genotypes or phases were included. On Figure 3C only two biological replicates (R2 and R3) of the Set3-9myc yeast phase ChIP-Seq samples were included. Mapped reads were extended with the length of the MACS d parameter (∼150 bp) prior to visualization. The complete ChIP-Seq dataset including chromosomal coordinates and RPKM values of all ORFs and tRNA clusters is found in Table S4.

Data availability

Data have been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE38427.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SudberyP, GowN, BermanJ (2004) The distinct morphogenic states of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol 12 : 317–324.

2. ThompsonDS, CarlislePL, KadoshD (2011) Coevolution of morphology and virulence in Candida species. Eukaryot Cell 10 : 1173–1182.

3. GowNA, BrownAJ, OddsFC (2002) Fungal morphogenesis and host invasion. Curr Opin Microbiol 5 : 366–371.

4. SavilleSP, LazzellAL, BryantAP, FretzenA, MonrealA, et al. (2006) Inhibition of filamentation can be used to treat disseminated candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50 : 3312–3316.

5. WhitewayM, BachewichC (2007) Morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Annu Rev Microbiol 61 : 529–553.

6. ShapiroRS, RobbinsN, CowenLE (2011) Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance, and disease. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75 : 213–267.

7. NobleSM, FrenchS, KohnLA, ChenV, JohnsonAD (2010) Systematic screens of a Candida albicans homozygous deletion library decouple morphogenetic switching and pathogenicity. Nat Genet 42 : 590–598.

8. HomannOR, DeaJ, NobleSM, JohnsonAD (2009) A phenotypic profile of the Candida albicans regulatory network. PLoS Genet 5: e1000783.

9. LuY, SuC, MaoX, RanigaPP, LiuH, et al. (2008) Efg1-mediated recruitment of NuA4 to promoters is required for hypha-specific Swi/Snf binding and activation in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 19 : 4260–4272.

10. LuY, SuC, WangA, LiuH (2011) Hyphal development in Candida albicans requires two temporally linked changes in promoter chromatin for initiation and maintenance. PLoS Biol 9: e1001105.

11. KadoshD, JohnsonAD (2005) Induction of the Candida albicans filamentous growth program by relief of transcriptional repression: a genome-wide analysis. Mol Biol Cell 16 : 2903–2912.

12. LuY, SuC, LiuH (2012) A GATA Transcription Factor Recruits Hda1 in Response to Reduced Tor1 Signaling to Establish a Hyphal Chromatin State in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002663.

13. RamanSB, NguyenMH, ZhangZ, ChengS, JiaHY, et al. (2006) Candida albicans SET1 encodes a histone 3 lysine 4 methyltransferase that contributes to the pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis. Mol Microbiol 60 : 697–709.

14. Lopes da RosaJ, BoyartchukVL, ZhuLJ, KaufmanPD (2010) Histone acetyltransferase Rtt109 is required for Candida albicans pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 1594–1599.

15. HniszD, MajerO, FrohnerIE, KomnenovicV, KuchlerK (2010) The Set3/Hos2 histone deacetylase complex attenuates cAMP/PKA signaling to regulate morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000889.

16. PijnappelWW, SchaftD, RoguevA, ShevchenkoA, TekotteH, et al. (2001) The S. cerevisiae SET3 complex includes two histone deacetylases, Hos2 and Hst1, and is a meiotic-specific repressor of the sporulation gene program. Genes Dev 15 : 2991–3004.

17. WangA, KurdistaniSK, GrunsteinM (2002) Requirement of Hos2 histone deacetylase for gene activity in yeast. Science 298 : 1412–1414.

18. KimT, BuratowskiS (2009) Dimethylation of H3K4 by Set1 recruits the Set3 histone deacetylase complex to 5′ transcribed regions. Cell 137 : 259–272.

19. LiuOW, ChunCD, ChowED, ChenC, MadhaniHD, et al. (2008) Systematic genetic analysis of virulence in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell 135 : 174–188.

20. DingSL, LiuW, IliukA, RibotC, ValletJ, et al. (2010) The tig1 histone deacetylase complex regulates infectious growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Cell 22 : 2495–2508.

21. ZhangY, LiuT, MeyerCA, EeckhouteJ, JohnsonDS, et al. (2008) Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9: R137.

22. NantelA, DignardD, BachewichC, HarcusD, MarcilA, et al. (2002) Transcription profiling of Candida albicans cells undergoing the yeast-to-hyphal transition. Mol Biol Cell 13 : 3452–3465.

23. NobileCJ, FoxEP, NettJE, SorrellsTR, MitrovichQM, et al. (2012) A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell 148 : 126–138.

24. NobileCJ, NettJE, HerndayAD, HomannOR, DeneaultJS, et al. (2009) Biofilm matrix regulation by Candida albicans Zap1. PLoS Biol 7: e1000133.

25. AskewC, SellamA, EppE, HoguesH, MullickA, et al. (2009) Transcriptional regulation of carbohydrate metabolism in the human pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000612.

26. LavoieH, HoguesH, MallickJ, SellamA, NantelA, et al. (2010) Evolutionary tinkering with conserved components of a transcriptional regulatory network. PLoS Biol 8: e1000329.

27. LassakT, SchneiderE, BussmannM, KurtzD, ManakJR, et al. (2011) Target specificity of the Candida albicans Efg1 regulator. Mol Microbiol 82 : 602–618.

28. UhlMA, BieryM, CraigN, JohnsonAD (2003) Haploinsufficiency-based large-scale forward genetic analysis of filamentous growth in the diploid human fungal pathogen C.albicans. EMBO J 22 : 2668–2678.

29. MouZ, KennyAE, CurcioMJ (2006) Hos2 and Set3 promote integration of Ty1 retrotransposons at tRNA genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 172 : 2157–2167.

30. LenstraTL, BenschopJJ, KimT, SchulzeJM, BrabersNA, et al. (2011) The specificity and topology of chromatin interaction pathways in yeast. Mol Cell 42 : 536–549.

31. WeinerA, ChenHV, LiuCL, RahatA, KlienA, et al. (2012) Systematic dissection of roles for chromatin regulators in a yeast stress response. PLoS Biol 10: e1001369.

32. LeeJS, SmithE, ShilatifardA (2010) The language of histone crosstalk. Cell 142 : 682–685.

33. HenikoffS, ShilatifardA (2011) Histone modification: cause or cog? Trends Genet 27 : 389–396.

34. Alejandro-OsorioAL, HuebertDJ, PorcaroDT, SonntagME, NillasithanukrohS, et al. (2009) The histone deacetylase Rpd3p is required for transient changes in genomic expression in response to stress. Genome Biol 10: R57.

35. LohseMB, JohnsonAD (2010) Temporal anatomy of an epigenetic switch in cell programming: the white-opaque transition of C. albicans. Mol Microbiol 78 : 331–343.

36. SellamA, HoguesH, AskewC, TebbjiF, van Het HoogM, et al. (2010) Experimental annotation of the human pathogen Candida albicans coding and noncoding transcribed regions using high-resolution tiling arrays. Genome Biol 11: R71.

37. BuratowskiS (2009) Progression through the RNA polymerase II CTD cycle. Mol Cell 36 : 541–546.

38. EgloffS, MurphyS (2008) Cracking the RNA polymerase II CTD code. Trends Genet 24 : 280–288.

39. EgloffS, DienstbierM, MurphyS (2012) Updating the RNA polymerase CTD code: adding gene-specific layers. Trends Genet

40. KimT, XuZ, Clauder-MünsterS, SteinmetzL, BuratowskiS (2012) Set3 HDAC mediates effects of overlapping noncoding transcription on gene induction kinetics. Cell doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.016.

41. NobleSM, JohnsonAD (2005) Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 4 : 298–309.

42. FrohnerIE, BourgeoisC, YatsykK, MajerO, KuchlerK (2009) Candida albicans cell surface superoxide dismutases degrade host-derived reactive oxygen species to escape innate immune surveillance. Mol Microbiol 71 : 240–252.

43. ReussO, VikA, KolterR, MorschhauserJ (2004) The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341 : 119–127.

44. HerndayAD, NobleSM, MitrovichQM, JohnsonAD (2010) Genetics and molecular biology in Candida albicans. Methods Enzymol 470 : 737–758.

45. TrapnellC, PachterL, SalzbergSL (2009) TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25 : 1105–1111.

46. TrapnellC, WilliamsBA, PerteaG, MortazaviA, KwanG, et al. (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28 : 511–515.

47. LangmeadB, TrapnellC, PopM, SalzbergSL (2009) Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25.

48. MortazaviA, WilliamsBA, McCueK, SchaefferL, WoldB (2008) Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods 5 : 621–628.

49. LiH, FischleW, WangW, DuncanEM, LiangL, et al. (2007) Structural basis for lower lysine methylation state-specific readout by MBT repeats of L3MBTL1 and an engineered PHD finger. Mol Cell 28 : 677–691.

50. SaliA, BlundellTL (1993) Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 234 : 779–815.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Defining the Pathways Underlying the Prolonged PR Interval in Atrioventricular Conduction DiseaseČlánek Translation in Giant Viruses: A Unique Mixture of Bacterial and Eukaryotic Termination Schemes

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 12

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Mystery Unraveled: Essentiality of RNase III in Is Caused by Resident Prophages

- Defining the Pathways Underlying the Prolonged PR Interval in Atrioventricular Conduction Disease

- Insertion/Deletion Polymorphisms in the Promoter Are a Risk Factor for Bladder Exstrophy Epispadias Complex

- Mi2β Is Required for γ-Globin Gene Silencing: Temporal Assembly of a GATA-1-FOG-1-Mi2 Repressor Complex in β-YAC Transgenic Mice

- Dissection of a Quantitative Trait Locus for PR Interval Duration Identifies as a Novel Modulator of Cardiac Conduction

- Dnmt3a Protects Active Chromosome Domains against Cancer-Associated Hypomethylation

- Construction of a Global Pain Systems Network Highlights Phospholipid Signaling as a Regulator of Heat Nociception

- Genes Contributing to Pain Sensitivity in the Normal Population: An Exome Sequencing Study

- Identification of , a Locus Controlling Dominant Resistance to Autoimmune Orchitis, as Kinesin Family Member 1C

- ATX1-Generated H3K4me3 Is Required for Efficient Elongation of Transcription, Not Initiation, at ATX1-Regulated Genes

- Dynamic and Differential Regulation of Stem Cell Factor FoxD3 in the Neural Crest Is Encrypted in the Genome

- Identification of Novel Type 2 Diabetes Candidate Genes Involved in the Crosstalk between the Mitochondrial and the Insulin Signaling Systems

- The Genetic Architecture of Adaptations to High Altitude in Ethiopia

- Population Genomics of the Endosymbiont in

- Translation in Giant Viruses: A Unique Mixture of Bacterial and Eukaryotic Termination Schemes

- Testicular Differentiation Occurs in Absence of R-spondin1 and Sox9 in Mouse Sex Reversals

- A Yeast GSK-3 Kinase Mck1 Promotes Cdc6 Degradation to Inhibit DNA Re-Replication

- Genetic Adaptation Associated with Genome-Doubling in Autotetraploid

- The Essential Function of RNase III Is to Silence Foreign Toxin Genes

- Long-Range Regulatory Polymorphisms Affecting a GABA Receptor Constitute a Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) for Social Behavior in

- A New Isolation with Migration Model along Complete Genomes Infers Very Different Divergence Processes among Closely Related Great Ape Species

- Chromosome Fragile Sites in Harbor Matrix Attachment Regions That May Be Associated with Ancestral Chromosome Rearrangement Events

- Genome-Wide Association Study Implicates Testis-Sperm Specific as a Susceptibility Locus for Impaired Acrosome Reaction in Stallions

- A Mechanism of Gene Amplification Driven by Small DNA Fragments

- Base Damage within Single-Strand DNA Underlies Hypermutability Induced by a Ubiquitous Environmental Agent

- Integrative Analysis of a Cross-Loci Regulation Network Identifies as a Gene Regulating Insulin Secretion from Pancreatic Islets

- Reciprocal Signaling between the Ectoderm and a Mesendodermal Left-Right Organizer Directs Left-Right Determination in the Sea Urchin Embryo

- Population Genomics of Sub-Saharan : African Diversity and Non-African Admixture

- Genome-Wide Fine-Scale Recombination Rate Variation in

- Deciphering the Transcriptional-Regulatory Network of Flocculation in

- On Lung Function and Interactions Using Genome-Wide Data

- Genome-Wide Joint Meta-Analysis of SNP and SNP-by-Smoking Interaction Identifies Novel Loci for Pulmonary Function

- The Effective Population Size of Malaria Mosquitoes: Large Impact of Vector Control

- Recessive Mutations in Implicate β-III Spectrin in Both Cognitive and Motor Development

- An Excess of Gene Expression Divergence on the X Chromosome in Embryos: Implications for the Faster-X Hypothesis

- Reduced Life- and Healthspan in Mice Carrying a Mono-Allelic MVA Mutation

- Natural Variation at the MATE Transporter Locus Reveals Cross-Talk between Fe Homeostasis and Zn Tolerance in

- Histone Deacetylase HDA6 Is Functionally Associated with AS1 in Repression of Genes in

- A Framework for the Establishment of a Cnidarian Gene Regulatory Network for “Endomesoderm” Specification: The Inputs of ß-Catenin/TCF Signaling

- A Polycomb Group Protein Is Retained at Specific Sites on Chromatin in Mitosis

- Diapause Formation and Downregulation of Insulin-Like Signaling via DAF-16/FOXO Delays Axonal Degeneration and Neuronal Loss

- Genes That Act Downstream of Sensory Neurons to Influence Longevity, Dauer Formation, and Pathogen Responses in

- A Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Reveals MAP Kinase Phosphatases as Key ERK Pathway Regulators during Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation

- Recurrent Targeted Genes of Hepatitis B Virus in the Liver Cancer Genomes Identified by a Next-Generation Sequencing–Based Approach

- Excessive Astrocyte-Derived Neurotrophin-3 Contributes to the Abnormal Neuronal Dendritic Development in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome

- Pre-Disposition and Epigenetics Govern Variation in Bacterial Survival upon Stress

- Controls Gliogenesis by Regulating the Transient Expression of the Gcm/Glide Fate Determinant

- Systems Genetic Analysis of Osteoblast-Lineage Cells

- Population Genomics of Inversion Polymorphisms in

- Spreading of Heterochromatin Is Limited to Specific Families of Maize Retrotransposons

- DNA Topoisomerases Maintain Promoters in a State Competent for Transcriptional Activation in

- A Histone Deacetylase Adjusts Transcription Kinetics at Coding Sequences during Morphogenesis

- Approaching the Functional Annotation of Fungal Virulence Factors Using Cross-Species Genetic Interaction Profiling

- Evidence for the Robustness of Protein Complexes to Inter-Species Hybridization

- Systematic Identification of Rhythmic Genes Reveals as a New Element in the Circadian Clockwork

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Dnmt3a Protects Active Chromosome Domains against Cancer-Associated Hypomethylation

- Population Genomics of Sub-Saharan : African Diversity and Non-African Admixture

- Excessive Astrocyte-Derived Neurotrophin-3 Contributes to the Abnormal Neuronal Dendritic Development in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome

- Pre-Disposition and Epigenetics Govern Variation in Bacterial Survival upon Stress

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání