-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaMismatch Repair–Independent Increase in Spontaneous Mutagenesis in Yeast Lacking Non-Essential Subunits of DNA Polymerase ε

Yeast DNA polymerase ε (Pol ε) is a highly accurate and processive enzyme that participates in nuclear DNA replication of the leading strand template. In addition to a large subunit (Pol2) harboring the polymerase and proofreading exonuclease active sites, Pol ε also has one essential subunit (Dpb2) and two smaller, non-essential subunits (Dpb3 and Dpb4) whose functions are not fully understood. To probe the functions of Dpb3 and Dpb4, here we investigate the consequences of their absence on the biochemical properties of Pol ε in vitro and on genome stability in vivo. The fidelity of DNA synthesis in vitro by purified Pol2/Dpb2, i.e. lacking Dpb3 and Dpb4, is comparable to the four-subunit Pol ε holoenzyme. Nonetheless, deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 elevates spontaneous frameshift and base substitution rates in vivo, to the same extent as the loss of Pol ε proofreading activity in a pol2-4 strain. In contrast to pol2-4, however, the dpb3Δdpb4Δ does not lead to a synergistic increase of mutation rates with defects in DNA mismatch repair. The increased mutation rate in dpb3Δdpb4Δ strains is partly dependent on REV3, as well as the proofreading capacity of Pol δ. Finally, biochemical studies demonstrate that the absence of Dpb3 and Dpb4 destabilizes the interaction between Pol ε and the template DNA during processive DNA synthesis and during processive 3′ to 5′exonucleolytic degradation of DNA. Collectively, these data suggest a model wherein Dpb3 and Dpb4 do not directly influence replication fidelity per se, but rather contribute to normal replication fork progression. In their absence, a defective replisome may more frequently leave gaps on the leading strand that are eventually filled by Pol ζ or Pol δ, in a post-replication process that generates errors not corrected by the DNA mismatch repair system.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001209

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001209Summary

Yeast DNA polymerase ε (Pol ε) is a highly accurate and processive enzyme that participates in nuclear DNA replication of the leading strand template. In addition to a large subunit (Pol2) harboring the polymerase and proofreading exonuclease active sites, Pol ε also has one essential subunit (Dpb2) and two smaller, non-essential subunits (Dpb3 and Dpb4) whose functions are not fully understood. To probe the functions of Dpb3 and Dpb4, here we investigate the consequences of their absence on the biochemical properties of Pol ε in vitro and on genome stability in vivo. The fidelity of DNA synthesis in vitro by purified Pol2/Dpb2, i.e. lacking Dpb3 and Dpb4, is comparable to the four-subunit Pol ε holoenzyme. Nonetheless, deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 elevates spontaneous frameshift and base substitution rates in vivo, to the same extent as the loss of Pol ε proofreading activity in a pol2-4 strain. In contrast to pol2-4, however, the dpb3Δdpb4Δ does not lead to a synergistic increase of mutation rates with defects in DNA mismatch repair. The increased mutation rate in dpb3Δdpb4Δ strains is partly dependent on REV3, as well as the proofreading capacity of Pol δ. Finally, biochemical studies demonstrate that the absence of Dpb3 and Dpb4 destabilizes the interaction between Pol ε and the template DNA during processive DNA synthesis and during processive 3′ to 5′exonucleolytic degradation of DNA. Collectively, these data suggest a model wherein Dpb3 and Dpb4 do not directly influence replication fidelity per se, but rather contribute to normal replication fork progression. In their absence, a defective replisome may more frequently leave gaps on the leading strand that are eventually filled by Pol ζ or Pol δ, in a post-replication process that generates errors not corrected by the DNA mismatch repair system.

Introduction

The accuracy by which DNA polymerases synthesize DNA is essential for maintaining genome stability and preventing carcinogenesis. Eukaryotes utilize many DNA polymerases, with different properties, during DNA replication and in DNA repair [1]. DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ), DNA polymerase ε (Pol ε) and DNA polymerase α (Pol α) (with associated primase activity) are required for bulk synthesis of DNA during chromosomal replication [2]. Several studies have suggested that there is a division of labor between Pol δ and Pol ε at the replication fork. Genetic and biochemical studies position Pol δ on the lagging strand [3]–[6], whereas Pol ε was shown to participate in the synthesis of the leading strand in S. cerevisiae [7]. These studies were preceded by genetic experiments showing that Pol ε and Pol δ proofread opposite strands [8]–[10]. In addition, the Pol ε 3′→ 5′ –exonuclease activity, contrary to the Pol δ 3′→ 5′ –exonuclease activity, does not participate in the correction of errors made by Pol α. This suggests that the proofreading function of Pol ε is restricted to the leading strand [11], while the exonuclease activity of Pol δ, or perhaps another exonuclease, may proofread both strands [12].

The organization of the replication fork during normal DNA replication, with Pol ε on the leading strand and Pol δ on the lagging strand [6], [7], can be disrupted by DNA lesions or sequence contexts in an undamaged template that influence the ability of the replicative polymerase to remain processive [12]–[14]. When polymerases dissociate, the replication machinery must accommodate to complete the replication process and if possible maintain high fidelity. To accomplish this, a variety of strategies are used, including translesion synthesis and recombination pathways [15]. DNA lesions which disengage Pol δ or Pol ε result in single-stranded gaps which are filled in during post-replication repair [16]–[18]. Furthermore, biochemical experiments have shown that collisions between DNA polymerase and transcribing RNA polymerase leads to the abortion of DNA synthesis followed by a reinitiation event when the RNA transcript is used as a primer [19]. To summarize, post-replication repair processes, uncoupled from the replication fork, are likely to occur on both leading and lagging strands to complete DNA replication.

Pol α, Pol δ and Pol ε are all composed of several subunits encoded by separate genes. Besides the catalytic subunit, Pol2 (256 kDa), yeast Pol ε consists of three auxiliary subunits, Dpb2 (79 kDa), Dpb3 (23 kDa) and Dpb4 (22 kDa) [20]. DPB2 is an essential gene in yeast with an unknown function [21], yet it is required for early steps in DNA replication and is regulated by Cdc28 kinase [22], [23]. Recently dpb2 mutations that increase spontaneous mutagenesis were found in S. cerevisiae, suggesting that the second subunit contributes to the fidelity of DNA replication by an unknown mechanism [24], [25]. DPB3 and DPB4 are non-essential genes. Deletion of DPB3 was previously shown to result in a modest mutator effect [26], [27]. Dpb3 and Dpb4 both contain histone fold motifs that are known to be important in protein-protein interactions [28], [29]. Interestingly, Dpb4 is a component of a chromatin-remodeling complex in S. cerevisiae, ISW2, corresponding to the CHRAC complex found in Drosophila and humans [30], [31].

The structure of the Pol ε holoenzyme revealed two large domains separated by a flexible hinge [32]. It was suggested that the tail domain of Pol ε was comprised of the Dpb2, Dpb3 and Dpb4 subunits and was important for the binding to and association with the primer-template dsDNA during DNA synthesis [32]. A purified Dpb3-Dpb4 heterodimer was shown to possess dsDNA binding properties, which in part could explain the properties of the tail-domain [29]. However, this does not exclude the possibility that Dpb2 by itself has properties which allow the tail-domain to interact with dsDNA even without Dpb3 and Dpb4.

In this work, we address whether the Dpb3 and Dpb4 subunits have an effect on the biochemical properties of Pol ε and the fidelity of replication in yeast via a function at the tail-domain of Pol ε. We find that Dpb3 and Dpb4 are important for the processivity of Pol ε polymerase and exonuclease activities, suggesting a role of these two subunits in stabilization of Pol ε interaction with primer-template DNA. Evidently this indirectly affects the fidelity of the overall DNA replication process, since deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 increases both spontaneous frameshift and base substitution mutagenesis, despite an unchanged fidelity of the purified Pol2/Dpb2 complex. A genetic analysis suggests that REV3 contributes to the increased mutation rate in dpb3Δdpb4Δ and the mutational intermediates escape correction by the mismatch repair system.

Results

Influence of dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ on spontaneous mutagenesis and interaction with pol2-4

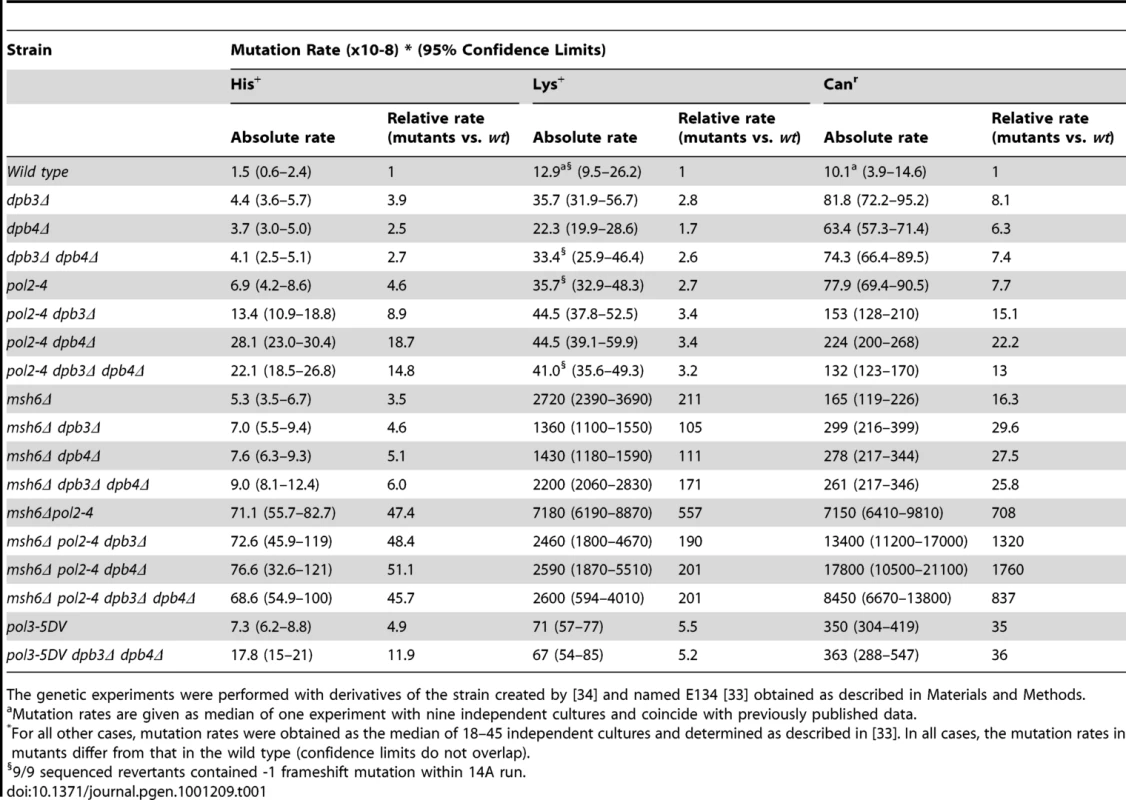

To investigate the in vivo role of the Pol ε accessory subunits Dpb3 and Dpb4, we constructed yeast strains wherein either DPB3, DPB4 or both of these genes were deleted. The frequency of spontaneous mutations in these strains was measured in two reversion assays and one forward mutation assay. We studied the his7-2 and lys2::insE-A14 reversion alleles to score frameshift mutations. The his7-2 allele contains a single base pair deletion in a run of 8 T(A) and revert via +1 insertions or -2 deletions [33]. The lys2::insE-A14 allele contains a homonucleotide run of 14 T(A) and revert mainly via -1 mutations [34]. The forward mutation assay scores various types of mutations that inactivate the CAN1 gene and result in resistance to canavanine. We found that the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ double deletion has a moderate mutator effect in all assays. Mutation rates for his7-2 reversions and lys2::insE-A14 were increased 2.7 and 2.6-fold when compared to the wt E134 strain (Table 1). The mutation rate in the forward mutation assay for canavanine resistance was increased 7.4-fold compared to the wt strain (Table 1). The individual contribution of dpb3Δ or dpb4Δ was comparable to the effect of the deletion of both these genes (dpb3Δdpb4Δ) (Table 1). A proofreading deficient allele of the catalytic subunit, pol2-4, introduced in the same genetic background resulted in an elevation of the mutation rates similar to the dpb3Δdpb4Δ strain (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Spontaneous mutation rates in strains with dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ, pol2-4 mutation, msh6Δ, and pol-5DV.

The genetic experiments were performed with derivatives of the strain created by [34] and named E134 [33] obtained as described in Materials and Methods. To determine if the participation of Pol ε in DNA replication depends on DPB3 and DPB4, we combined dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, or dpb3Δ dpb4Δ with the pol2-4 mutation. The analysis revealed different genetic interactions. Combining dpb3Δ and pol2-4 led to an additive effect on his7-2 reversion (Table 1). A higher than additive increase in mutation rate was observed with the his7-2 allele when pol2-4 was combined with dpb4Δ or dpb3Δ dpb4Δ (Table 1). Reversions scored in the lys2::insE-A14 allele revealed a close to epistatic interaction between pol2-4, dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ, and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ (Table 1). The pol2-4 mutation itself elevated the reversion rate of the lys2::insE-A14 allele 2.7-fold, which agrees with previous results [35], [36]. The forward mutation assay with the CAN1 gene revealed an additive effect of the pol2-4 mutation and the double dpb3Δ dpb4Δ deletion. An additive interaction was also found in the pol2-4dpb3Δ strain, but the combination of pol2-4 and dpb4Δ gave a higher than additive increase in mutation frequency (Table 1). The disparate genetic interactions of DPB3 and DPB4 with the proofreading activity of Pol2 could be due to the separate function of Dpb4 in a chromatin remodeling complex, ISW2 [30], [31], [37], [38]. However, there are no reports demonstrating that ISW2 influence the mutation rate in S. cerevisiae. Another possibility could be that Dpb3 and Dpb4 influence the fidelity of DNA synthesis by Pol ε.

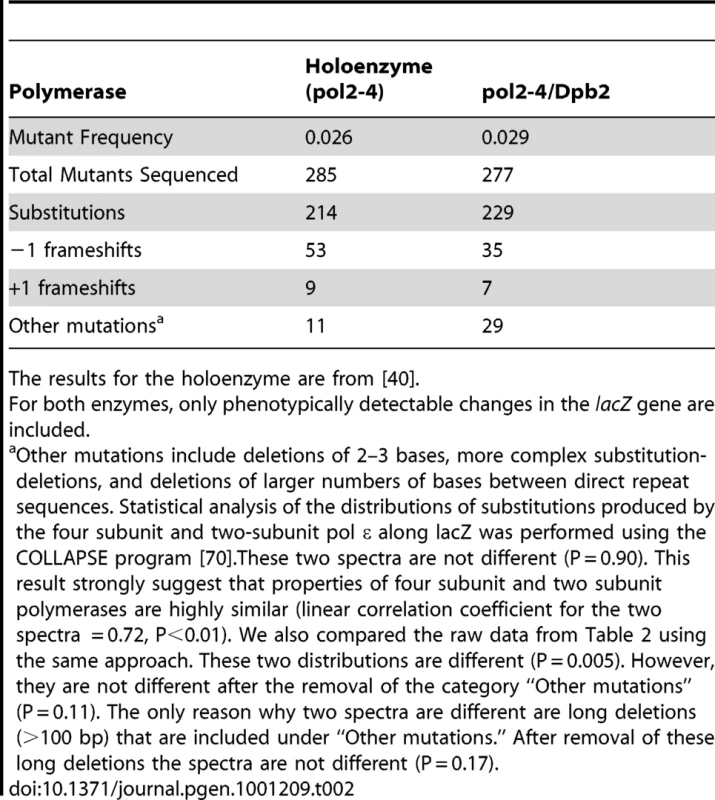

Fidelity of Pol2/Dpb2 in vitro

To measure the fidelity of Pol ε lacking Dpb3/Dpb4, we purified the wild type (i.e., exonuclease proficient) Pol2/Dpb2 complex and the exonuclease deficient pol2-4/Dpb2 complex, and then measured their fidelity in an M13mp2 gap-filling assay [39]. The lacZ mutant frequency of the DNA synthesis reaction products generated by the wild type Pol2/Dpb2 complex was 0.0018, comparable to the previously reported value of 0.0019 for the four-subunit Pol ε [40]. Both values are near the background lacZ mutant frequency of uncopied DNA, indicating that the exonuclease proficient Pol2/Dpb2 complex is highly accurate. The pol2-4/Dpb2 complex was less accurate, as expected because it is proofreading deficient. However, it was no less accurate than the exonuclease-deficient 4-subunit holoenzyme, as indicated by the similar lacZ mutant frequencies observed for both complexes (Table 2). To analyze if the error specificity of the 2-subunit enzyme differed from that of the holoenzyme, we sequenced 277 independent mutants generated by pol2-4/Dpb2, and compared the results to those reported in an earlier study [40] of 285 lacZ mutants generated by the holoenzyme. Comparable error specificity was observed (Table 2) for substitutions, frameshifts and other mutations. We conclude that the increased mutation rates in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain is unlikely to be due to a lower fidelity of DNA synthesis by Pol ε per se.

Tab. 2. Mutations generated by exonuclease-deficient Pol ε in vitro.

The results for the holoenzyme are from [40]. Genetic interaction between rev3Δ and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ

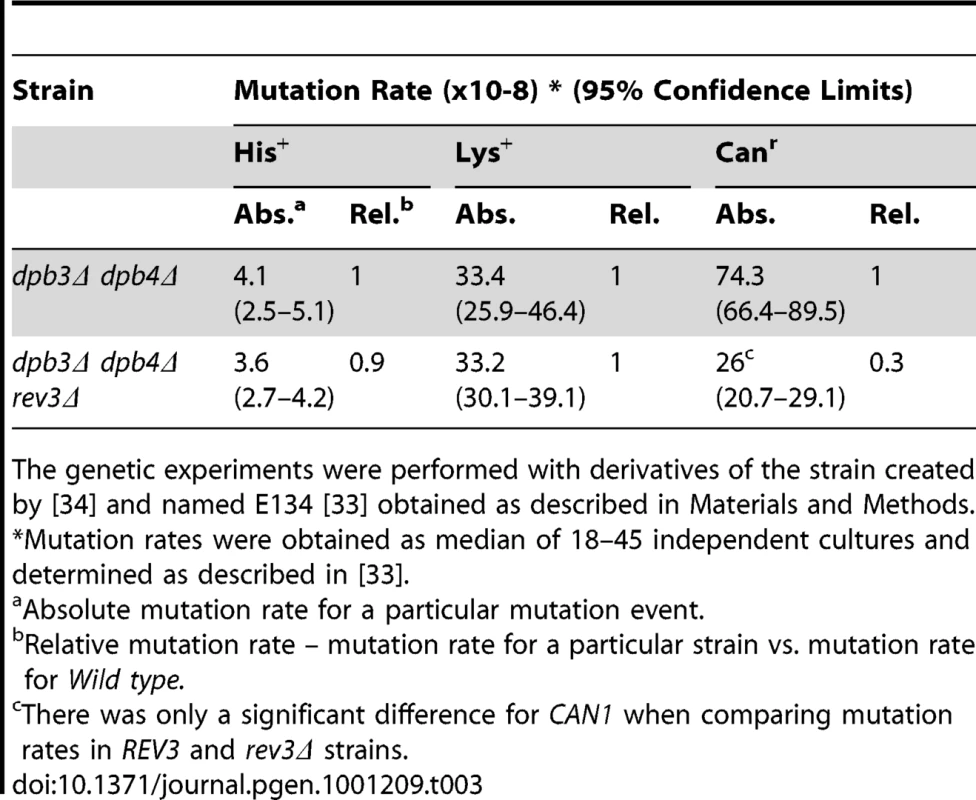

The REV3 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase ζ (Pol ζ), which is known to be a major contributor to both spontaneous and DNA damage inducible mutagenesis in wild type strains and in strains with defects in other DNA polymerases [27], [41], [42]. Yeast Pol ζ has relatively high fidelity for single-base insertions and deletions, and somewhat lower fidelity for base substitutions [43]. Deletion of the REV3 gene suppresses mutagenesis in CAN1 in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain but not mutagenesis in the his7-2 or lys2::insE-A14 allele (Table 3). Thus, the increase in frameshift mutagenesis observed in the his7-2 and lys2::insE-A14 alleles is Pol ζ-independent.The independence of frameshift his7-2 and lys2::insE-A14 reversion from Pol ζ is consistent with an earlier observation that replication defects (e.g. in Pol δ mutant, the pol3-Y708allele) cause Pol ζ dependent mutagenesis for base substitutions only [44].

Tab. 3. Influence of rev3Δ on spontaneous mutagenesis in the strain lacking DPB3 and DPB4 genes.

The genetic experiments were performed with derivatives of the strain created by [34] and named E134 [33] obtained as described in Materials and Methods. Genetic interaction between Pol δ and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ

Published results suggest that Pol δ can proofread errors made by Pol α [11]. To ask if Pol δ proofreads errors generated in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain, we combined the proofreading deficient Pol δ allele pol3-5DV with dpb3Δ dpb4Δ. The pol3-5DV dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain was viable, in contrast to pol3-01 pol2-4 and pol3-5DV pol2-4 haploid strains [9]. The mutation rates in pol3-5DV dpb3Δ dpb4Δ and pol3-5DV in the CAN1 gene were similar (Table 1). In contrast, the reversion rate of the his7-2 allele was greater than additive in the pol3-5DV dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain, when compared to the pol3-5DV strain and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain. We conclude that Pol δ has the capacity to proofread a fraction of frameshift errors that occur in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain, but there could also be some other 3′→5′ exonuclease that participates in the process.

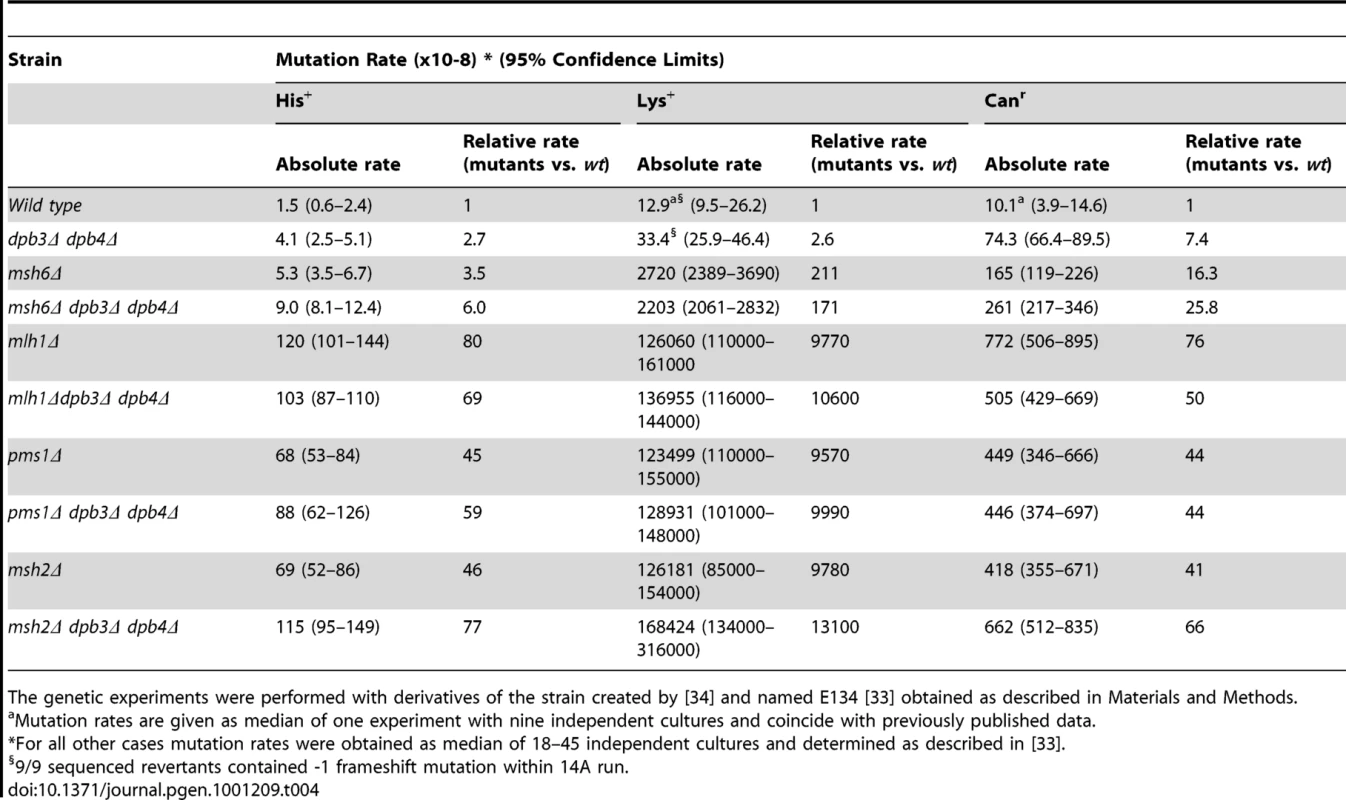

Genetic interaction with MSH6, MSH2, MLH1, and PMS1

The mismatch repair protein Msh6 is involved in recognizing a subset of replication errors, specifically single base mismatches and small insertion-deletion intermediates [45]. Although less severe than msh2Δ, pms1Δ or mlh1Δ, inactivation of the MSH6 gene results in a strong increase in mutagenesis (Table 4). For instance, msh6Δ leads to a dramatic increase of lys2::insE-A14 allele reversion rates as a result of single nucleotide deletions (Table 4, [34], [35]). To ask whether DPB3 and DPB4 interact with the mismatch repair system we measured the mutation rates in strains with dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ deletions in an Msh6-deficient background to score for base-base mismatches and small insertion-deletion errors.

Tab. 4. Spontaneous mutation rates in strains with dpb3Δ dpb4Δ and mismatch repair deficiency.

The genetic experiments were performed with derivatives of the strain created by [34] and named E134 [33] obtained as described in Materials and Methods. The combination of the msh6Δ with the dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ gave an additive increase in the his7-2 reversion and can1 mutation rates (Table 1). The strong synergetic interaction between proofreading defects (pol2-4, pol3-01) and defects in the mismatch repair system was previously observed for short homopolymeric runs and base substitutions, but not for long homopolymeric runs, such as the A14 run in the lys2::insE-A14 allele [34], [35], [46]. In agreement with that, we observed a synergetic interaction between pol2-4 and msh6Δ when mutation rates in a pol2-4 msh6Δ strain were estimated in the his7-2 and CAN1 loci (Table 1). In the short 8A run of the his7-2 allele, neither the deletion of DPB3 or DPB4 nor both genes affected the mutation rate of the pol2-4 msh6Δ. The multiplicative interaction of pol2-4 and dpb4Δ is absent in the msh6Δ background. The mutation rate in the lys2::insE-A14 gave a complex interaction between msh6Δ and dpb3Δ and dpb4Δ. The mutation rate was somewhat lower (though not statistically significant, see overlapping confidence limits in Table 1) when either dpb3Δ or dpb4Δ was combined with msh6Δ, than when the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ was combined with msh6Δ. When pol2-4 was added to the msh6Δ strain, the combination with dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ or dpb3Δ dpb4Δ gave a mutation rate that was one third of the mutation rate in the pol2-4 msh6Δ strain. At present, it is not clear why this small reduction in mutation rate occurs.

The lack of a synergetic interaction between dpb3Δ, dpb4Δ and msh6Δ was unexpected and led us to ask if this was also true for other genes that are required for mismatch repair. Msh2 forms a heterodimer with either Msh3 or Msh6. Thus, msh6Δ strains still have active Msh2-Msh3 which corrects most replication errors. To completely abolish mismatch repair we deleted MSH2, MLH1, or PMS1. The combination of mlh1Δ or pms1Δ with dpb3Δ dpb4Δ did not reveal a strong synergetic interaction on the his7-2 reversion or can1 mutation rates (Table 4). The combination of msh2Δ and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ gave only a two-fold increase in mutation rate on his7-2 reversions and no increase on can1 mutation rates. These data indicate that dpb3Δ dpb4Δ do not act in series with the mismatch repair system.

DNA sequence changes in the CAN1 gene in strains lacking DPB3 and DPB4 genes

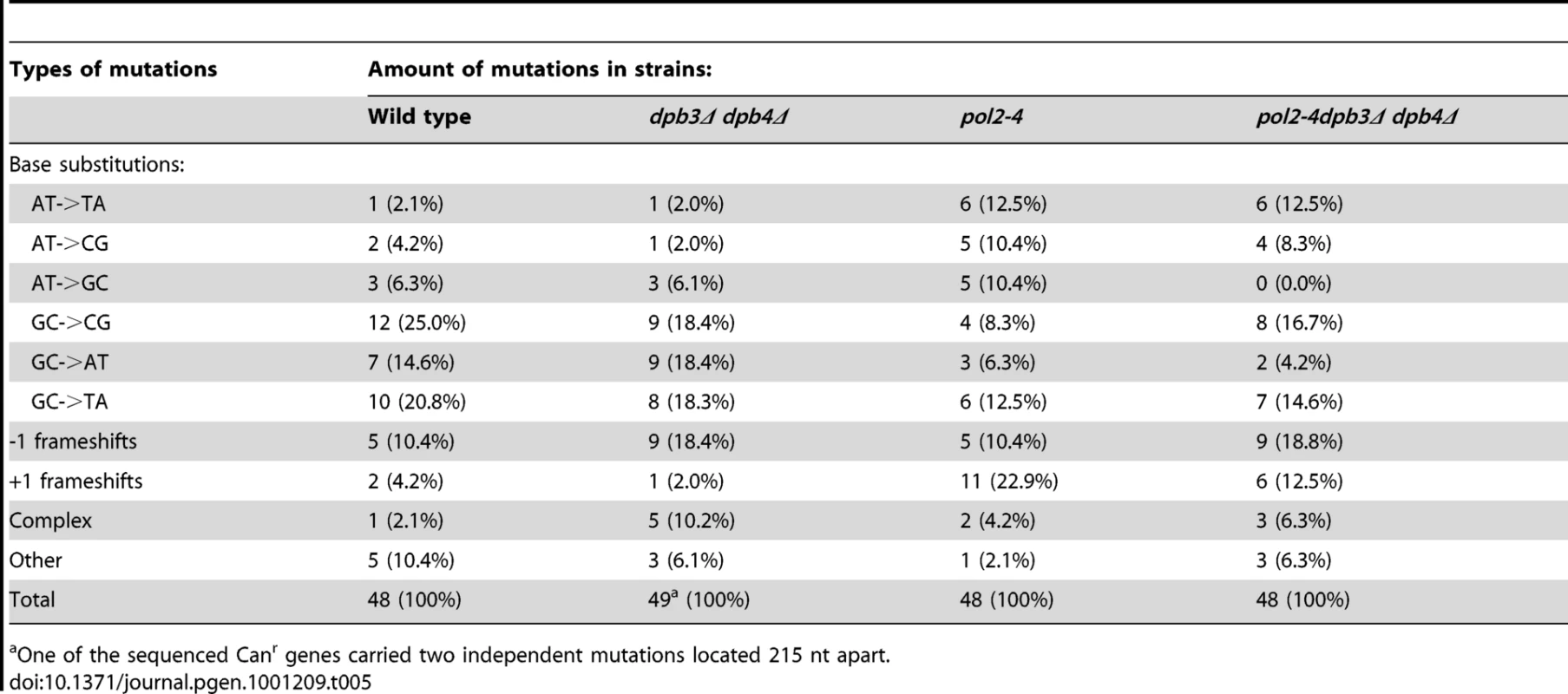

Forward mutations giving resistance to canavanine can arise by many different mechanisms. Earlier studies have shown that even a small collection of sequenced can1 mutants can reveal significant changes in the mutation spectra (e.g. upon deletion of POL32, a small subunit of Pol δ, or inactivation of Pol ε proofreading with the pol2-4 allele [9], [47]). To analyze if the deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 might drastically influence the distribution of types of mutations in the CAN1 gene, we sequenced 48 can1 mutants in four isogenic strains: wt, dpb3Δdpb4Δ, pol2-4 and pol2-4 dpb3Δdpb4Δ (Table 5). The difference between strains carrying the pol2-4 allele and carrying POL2 was statistically significant according to a modified Pearson χ2 test of spectra homogeneity (see Table S1 and Table S2). There was a characteristic reduction of CG→GC changes and an increase of frameshift mutations in the pol2-4 spectrum (Table 5). The comparison between wt and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ or pol2-4 and pol2-4 dpb3Δ dpb4Δ showed that the deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 did not give a statistically significant alteration in mutation spectra (see Table S1). The sample size was insufficient to demonstrate the enhancement of an error signature for Pol ζ despite the increased contribution of REV3 dependent mutations in CAN1. We conclude that the CAN1 mutations appearing in the pol2-4 background and in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ mutants arise by different mechanisms.

Tab. 5. CAN1 forward mutation spectrum.

One of the sequenced Canr genes carried two independent mutations located 215 nt apart. Dpb3 and Dpb4 subunits are required for both processive polymerase and processive 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Pol ε

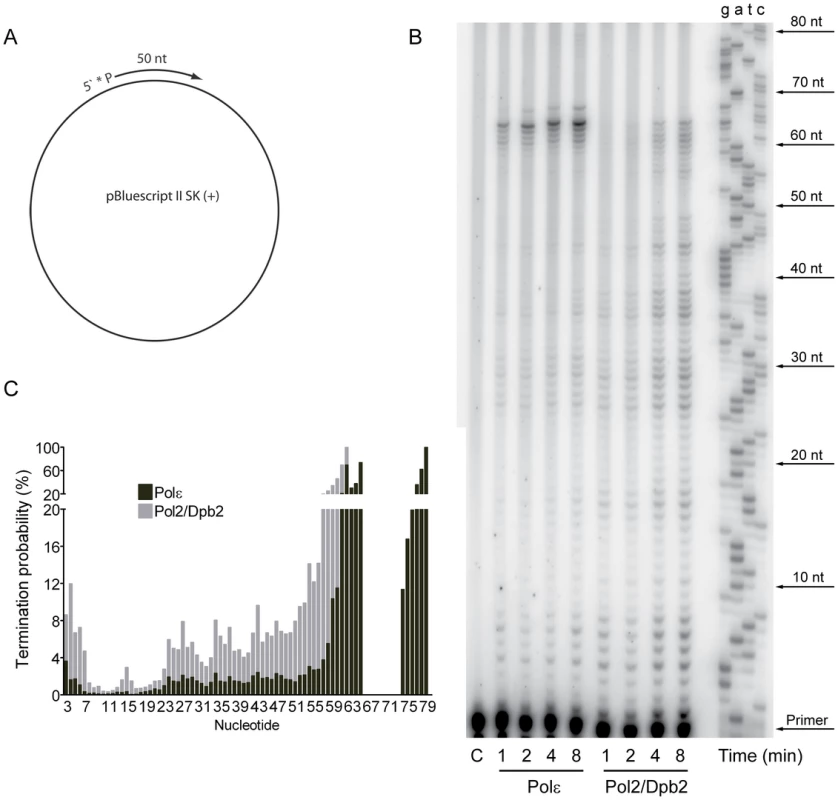

The contribution of Pol ζ to the elevated mutation rates suggested that a Pol2/Dpb2 complex does not support a fully functional replisome. To ask if Dpb3 and Dpb4 influence the processivity of Pol ε, we purified a Pol2/Dpb2 complex with an intact polymerase and exonuclease activity. We measured the processivity of the polymerase activity on a singly-primed, single stranded circular DNA template under single-hit conditions [48]. We found that a 40-fold molar excess of the primer-template over Pol ε and a 20-fold molar excess of the primer-template over Pol2/Dpb2 fit the criteria for single-hit conditions. The processivity of Pol ε on this template was comparable to a previous report, with a strong pause-site 63 nucleotides from the primer (Figure 1B) [48]. The absence of Dpb3 and Dpb4 from Pol ε lowers the processivity of polymerization. Some products reached a length of 63 nucleotides, but products were terminated with a higher probability at numerous positions (Figure 1C). On average, the termination probability at each position on the template increased two to three-fold for Pol2/Dpb2 as compared to the four subunit Pol ε.

Fig. 1. Processivity of the polymerase activity of Pol ε holoenzyme and Pol2/Dpb2 complex.

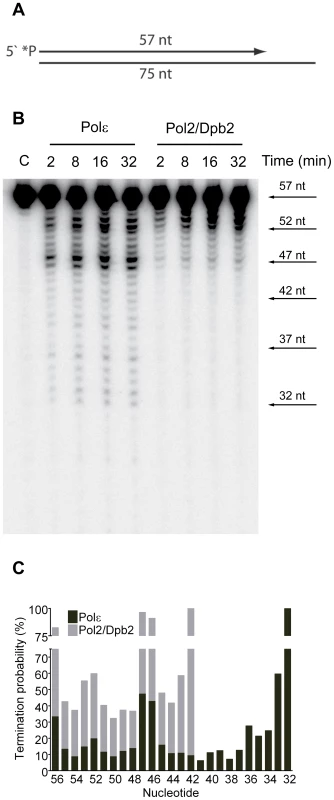

(A) A 50 nt long, 32P-5′end-labeled, oligonucleotide was annealed to pBluescript II SK (+) ssDNA and used as a DNA substrate in the polymerization assay. (B) Shown is the image of extension products generated by four-subunit Pol ε and a two-subunit Pol2/Dpb2 complex, separated on a 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (for details see Materials and Methods). A DNA sequencing ladder with the identical template was used as a molecular weight marker on the right hand. Reaction times are indicated under each lane. (C) The termination probability at each position on the template was calculated for the four-subunit Pol ε holoenzyme and Pol2/Dpb2 complex (for details see Materials and Methods). Next, we asked if the Dpb3 and Dpb4 subunits are required for processive exonucleolytic degradation of DNA. We carried out an exonuclease assay with a 57-nt long primer annealed to a 75-nt long template to generate 57-nt dsDNA region. Again, the conditions were empirically determined to achieve single-hit kinetics. This time a five-fold molar excess of primer-template over the four-subunit Pol ε was used, whereas an equimolar ratio of primer-template and enzyme was used for Pol2/Dpb2. We found that the Pol ε holoenzyme efficiently degraded the first 24 nucleotides of the primer (Figure 2B). At this point only ∼32 nt of the primer remained. This correlates well with the minimal length of dsDNA required for processive synthesis of DNA by Pol ε [32]. By analogy, the processivity of Pol ε exonuclease activity could depend on a specific interaction between the tail-domain and the dsDNA. In agreement with this hypothesis, we found the exonuclease activity of Pol2/Dpb2 to be less processive. Very few primers were degraded further than 11 nucleotides. On average, the termination probability at each position on the primer increased two to three-fold for Pol2/Dpb2 as compared to four-subunit Pol ε (Figure 2C). In addition, the absence of Dpb3 and Dpb4 did not result in a general inactivation of the exonuclease activity, since the exonuclease activity of the Pol2/Dpb2 complex and four-subunit Pol ε was comparable on single-stranded DNA (data not shown). We conclude that Dpb3 and Dpb4 stabilize the interaction of Pol ε with primer-template DNA and therefore positively affect the processivity of the polymerase and exonuclease activities of Pol ε. The removal of Dpb3 and Dpb4 would then lead to frequent dissociation of Pol ε that may disrupt the synthesis of the leading strand and potentially result in single-strand gaps.

Fig. 2. Processivity of the exonuclease activity of Pol ε holoenzyme and Pol2/Dpb2 complex.

(A) A 57 nt long, 32P-5′end-labeled, oligonucleotide was annealed to a 75 nt oligonucleotide, creating a primer-template to be used as a DNA substrate in the exonuclease assay. (B) Shown is the image of degradation products generated by four-subunit Pol ε and two-subunit Pol2/Dpb2 complex, separated on a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (for details see Materials and Methods). Reaction times are indicated above each lane. (C) The termination probability at each position on the template was calculated for the four-subunit Pol ε holoenzyme and Pol2/Dpb2 complex (for details see Materials and Methods). Discussion

In general, defects at the replication fork which give higher mutation rates act in series when combined with an inactivated mismatch repair system, i.e. mutator alleles of the catalytic subunit of Pol α, Pol δ, and Pol ε, temperature sensitive mutations of DPB2 (subunit of Pol ε), rfa1-29t, or the rfc1::Tn3 allele (subunit of clamp loader) [9], [24], [25], [49]–[52]. The interpretation has been that errors made in the proximity of the replication fork are corrected by mismatch repair and this results in a synergistic increase in mutation rates when mismatch repair is inactivated. In this study we show that deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 have the unique property among replication fork associated genes to give an increased mutation rate, but do not act in series with the mismatch repair system.

Defective replisome-driven mutagenesis

The unaltered fidelity of the Pol2/Dpb2 complex suggested that Dpb3 and Dpb4 are not important for the fidelity of DNA synthesis by Pol ε per se. In contrast, our genetic analysis demonstrated that the inactivation of DPB3 and DPB4 in yeast elevates the mutation rates comparable to the proofreading deficient pol2-4 allele of Pol ε. This suggests that the dynamics of the replication fork was altered in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain and the defect influenced the fidelity of the replisome. The hypothesis was supported by the observation that a Pol2/Dpb2 complex (lacking Dpb3 and Dpb4) was less processive both when polymerizing new DNA and degrading DNA (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Recently, it was shown that Pol ζ participates in the synthesis on undamaged DNA templates during defective replisome-induced mutagenesis as well as synthesis on stretches of single-stranded DNA carrying DNA lesions [42], [53]. Our genetic analysis supports a role for Pol δ and Pol ζ in spontaneous mutagenesis in dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strains since the mutagenesis in CAN1 depends in part on Pol ζ and Pol δ proofreading suppresses mutations in his7-2. One explanation for our observations could be that Pol ε dissociates more frequently from the template when DPB3 and DPB4 are deleted. After reinitiation, a gap is left that will be filled in by a post-replication repair mechanism analogous to what might happen when a replicative polymerase encounters a DNA lesion that cannot be bypassed. During this process, there will be time for the 3′-end to repeatedly melt and reanneal. A short homonucleotide run at the his7-2 site may frequently reanneal at the wrong nucleotide creating 1 or 2 nt loops. Such errors could be corrected by proofreading by the replicative polymerases [34] and the presence of Exo+ Pol δ during the gap-filling process would lead to decreased level of mutations. In a pol3-5DV strain, this proofreading is absent leading to a more than additive increase in mutation rate. In this scenario, we detect errors that appear not because of synthetic errors by Pol ε but instead due to an intermediate DNA structure that is prone to frameshift mutations. Thus a greater than additive interaction could be expected because Pol ε without Dpb3 and Dpb4 and proofreading by Pol δ act in series. The effect is detected because of the property of the reversion assay, which focuses on a single mutational pathway. We do not observe the same effects in the CAN1 gene because, in this case, we detect mutations generated by many different pathways. There is, however, a strong synergetic interaction between pol3-5DV and inactivation of mismatch repair. This can easily be explained by the proofreading deficiency of pol3-5DV that generates errors on the lagging strand at the replication fork. In addition, pol3-5DV is a mutator allele due to a defect in Okazaki fragment maturation [54]. Because of the multiple roles of Pol δ and its proofreading activity, more experiments are required to establish the nature of the effect of the pol3-5DV that we observed for his7-2 reversion.

The deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 could also result in lesser overall DNA synthesis by Pol ε on the leading strand. This is not likely to be the case as the mutation rate in the pol2-4 strain is not higher than in the pol2-4 dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain and the mutation signature from pol2-4 in the CAN1 gene is also found in the pol2-4 dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain, suggesting that exonuclease deficient pol2 synthesize approximately the same amount of DNA regardless if Dpb3 and Dpb4 are present or not.

It was earlier shown that defective replicative DNA polymerases (encoded by pol1-1, pol2-1, pol3t and pol3-Y708A) lead to an increased mutation rate that is in part dependent on Pol ζ. To our knowledge, the in vitro fidelity of the enzymes encoded by the four mutant alleles, pol1-1, pol2-1, pol3t and pol3-Y708A has not been measured. Thus, it is not firmly established if these alleles replicate DNA with a reduced fidelity. It is however, plausible that pol3-Y708A has a reduced fidelity based on analogous mutations in the Klenow fragment and RB69 DNA polymerase (discussed in [44]) and the position of Tyr708 in the active site [55]. The pol3-t mutant has a temperature sensitive mutation that also may affect the polymerase site and alter the fidelity of Pol3 [44], [55]. In cases where the effect of mismatch repair has been studied, clear synergy was observed for pol1-1 [56], pol3-t [57] and pol3-Y708A [44]. Mutant alleles encoding for polymerases that by itself synthesize DNA with a higher error-rate are likely to show synergy with the inactivation of mismatch repair, even if a substantial part of the mutations in the strain are REV3 dependent. The dual mechanism of mutator effects are exemplified by pol3-Y708A, which is likely to encode a polymerase that both generate errors that are corrected by mismatch repair and also induce PCNA ubiquitylation and a Pol ζ dependent increase of mutation rates. Here we present, for the first time, data on a mutant possessing two-subunit Pol ε with a confirmed unchanged error-rate in vitro, and a Pol ζ dependent increase in mutation rates, but no observed synergy with the inactivation of mismatch repair. This observation provides a distinction of errors made at the replication fork from errors made during postreplication DNA synthesis.

Errors depending on dpb3Δ dpb4Δ are not corrected by mismatch repair system

The deletions of DPB3 and DPB4 led to an increased mutation rate but did not act in series with msh6Δ, msh2Δ, pms1Δ or mlh1Δ. The lack of synergy could be due to an essential function for DPB3 or DPB4 in mismatch repair that inactivates the mismatch repair system. It was proposed earlier that the 3′→ 5′exonuclease activity of Pol ε could be involved in the excision step of mismatch repair in yeast [35]. However, the reversion rate at the lys2::insE-A14 allele in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain is too low to support a role for DPB3 and DPB4 in mismatch repair (compare dpb3Δ dpb4Δ with msh6Δ, msh2Δ, pms1Δ or mlh1Δ (Table 1 and Table 4)). Yet, there is a possibility that redundancy, due to genes with over-lapping functions in mismatch repair, suppress the mutation rate in dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strains. The possible redundancy only allows us to conclude that there is no evidence for a role of DPB3 and DPB4 (or Pol ε) in mismatch repair.

Whether mismatch repair is carried out in the near proximity of the replication fork or is uncoupled from the replication fork remains unclear. It has been proposed that mismatch repair may be physically linked to the replication fork [58], but DNA lesions from MNNG may induce a futile repair cycle where mismatch repair functions outside the S-phase [59]. Based on the genetic analysis of DPB3 and DPB4 we propose a model with two zones where mutagenesis occurs during DNA replication. The first zone is in the near proximity of the replication fork where Pol ζ - independent mutagenesis occurs and errors are corrected by mismatch repair. The second zone where Pol Δ and Pol ζ carries out post-replication repair is uncoupled from the replication fork. In this zone, Pol ζ-dependent mutagenesis occurs and errors are not at all or very inefficiently corrected by the mismatch repair system.

There is a series of observations upon which this model is based. We have clearly shown that the mutagenesis of the CAN1 gene in dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strains depends on Pol ζ and some mutation intermediates in the his7-2 allele are proofread by Pol Δ. Gap-filling during a post-replication repair process is likely to depend on PCNA, thus giving an advantage to Pol δ and Pol ζ over Pol ε to synthesize DNA since Pol ε has a slow on-rate on the PCNA-primer ternary structure [14], [48]. Recently, during defective-replisome-induced mutagenesis it was independently shown that Pol ζ replicates undamaged DNA under conditions when the dynamics of the replication fork is affected [42]. Mismatch repair is functional in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ background and yet there is no synergism. A hypothetical role for Rev3 in the close proximity of the replication fork would result in replication errors that are expected to be corrected by the mismatch repair system, analogous to errors produced by proofreading deficient Pol ε. At this position Rev3 would be a major contributor to the mutation rate in a msh2Δ strain, because Rev3 is responsible for at least half the mutation rate in the CAN1 gene in wild-type strains. The combination of rev3Δ and msh2Δ would then result in a substantially lower mutation rate; however, this was not the case. Instead, the mutation rate in a rev3Δmsh2Δ strain was comparable to a msh2Δ strain [47], suggesting that errors by Pol ζ are not efficiently corrected by mismatch repair. Our results demonstrate that errors generated by Pol ζ are not efficiently repaired by mismatch repair and are supported by evidence that some mutations generated by Pol ζ in a rad52Δ background are not corrected by mismatch repair in the lys2Δ A746-NR allele [60]. Based on the sum of these observations we propose that the deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 results in a decreased Pol ε processivity, generating a DNA substrate, which must be processed to some extent by Pol δ and Pol ζ during post-replication repair. This event occurs in a zone separated from active replication forks where the correction of errors by mismatch repair may be inefficient.

Alternative interpretations could be that synthesis by Pol ζ at stalled replication forks is not under mismatch repair surveillance. The transient dissociation of Pol ε would, in this case, create specific conditions when mismatch repair cannot function. Under these specific conditions any repair synthesis at the replication fork as well as post replicative repair synthesis in the single stranded gaps might escape MMR. The influence of chromatin on mutation rates and mismatch repair could also be an explanation. A potential mechanism could be that PCNA is post-translationally modified, due to check-point activation, blocking the interaction between mismatch repair proteins and PCNA. Regions with post-translationally modified PCNA would then be less efficiently repaired by mismatch repair.

Mismatch repair genes are not exclusively involved in correcting replication errors at the replication fork. Recently, it was shown that mismatch repair genes suppress recombination and promote translesion synthesis by Pol ζ in an assay measuring spontaneous mutation rates [60]. Other examples are immunoglobulin genes where mismatch repair together with Pol η is required for hypermutation at A/T pairs [61]. This is a paradox as the mismatch repair system promotes error-prone DNA synthesis by Pol ζ and Pol η in these two examples. The deletion of DPB3 and DPB4 unveils another example of how error-prone DNA synthesis is accepted to complete DNA synthesis and the mismatch-repair system does not correct the errors. The contribution of these Pol ζ dependent errors is small when compared to the error load which is corrected by mismatch repair at the proximity of the replication fork (compare CAN1 mutation rate in dpb3Δ dpb4Δ with msh2Δ (Table 4)). Yet, we found that the error-rate in the dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strain was comparable to the pol2-4 strain. The error-rate in pol2-4/pol2-4 mice was recently reported to be sufficient to support tumor development in mice [62]. Although the mechanism by which the error rates increases in pol2-4 and dpb3Δ dpb4Δ strains clearly differs, it is tempting to speculate that the inactivation of the mammalian homologues to DPB3 and DPB4 could result in defective replisomes, elevated mutation rates and tumor development.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are isogenic to E134 (MATα ade5-1 lys2::InsEA14 trp1-289 his7-2 leu2-3,112 ura3-52) [33]. The dpb3Δ mutant was kindly provided by P. Shcherbakova and is described in [27]. Other strains carrying dpb3Δ were obtained as described in [27]. The dpb4Δ mutants were constructed by transformation with PCR fragment carrying the hygB selectable marker and obtained using primers DPB4/kanMX-F (5′-ATGCCACCAAAAGGTTGGAGAAAAGACGCCCAAGGGAATTACCCCCGTACGCTGCAGGTCGAC) and DPB4/kanMX-R (5′-TTACGTTTGCTCAAGGTTTTGAACTCTAGTTTCTACATCTTGGCTATCGATGAATTCGAGCTCG) and the pAG32 plasmid as a template [63]. The disruption was confirmed by PCR analysis. The pol2-4 mutation was obtained as described in [64] using YIpJB1 plasmid carrying pol2-4 mutation [65]. The pol3-5DV mutation was obtained as described in [64] using plasmid p170-5DV [66].The presence of the pol2-4 mutation after integration into the chromosome was confirmed by SfcI digest of short PCR fragment encompassing mutation and DNA sequencing. Deletion of the MSH6 gene was obtained as described in [67]. The REV3 gene, encoding the catalytic subunit of Pol ζ, was deleted as described in [68]. Deletion of the MSH2 gene was obtained by transformation with PCR product obtained from the pRS305 plasmid using oligos MSH2_del_F (CTCCACTAGGCCAGAGCTAAAATTCTCTGATGTATCAGAGGAGAGCAGAGCAGATTGTACTGAGAGTGCACC) and MSH2_del_R (CCTTCACTTTTCTAATCCACTCTTTCAGTAAAGCCTTCAAACGAACGCATCTGTGCGGTATTTCACACCGC). The same strategy was used for deletion of the PMS1 and MLH1 gene. To obtain pms1Δ we used oligos PMS1_A (TATCAAAGCTAGATCATATTTCGTAATCCTTCGAAAATGAGCTCCAATCACGTAAAATATCTTGACCGCAGTTAA) and PMS1_S (AAGGTGTAAGCAAAAGGAACAGAGGTATATCCCTGTGAAATATTTATTTAGCCCCTATGAACATATTCCATT). The mlh1Δ was obtained by transformation with the PCR product obtained from the pRS306 plasmid using oligos MLH1_A (AAGTTAACACCTCTCAAAAACTTTGTATAGATCTGGAAGGTTGGCTATTTCCAACACCGCAGGGTAATAACTGAT) and MLH1_S (ATACGATAGTGATAGTAAATGGAAGGTAAAAATAACATAGACCTATCAATAAGCACGGTCACAGCTTGTCTGTAA).

Measurement of spontaneous mutation rates

The fluctuation tests to determine spontaneous mutation rates were, unless otherwise indicated, performed in two to five independent experiments of nine independent cultures each with independently obtained derivatives. Single two-day-old colonies from YPD plates were inoculated in 5 ml of liquid YPD medium and were grown with strong aeration for two days and processed as described [33].

Sequencing of His+ revertants and Canr mutants

Independent His+ revertants and Canr mutants were grown as small patches on YPD plates. Regions of corresponding genes were amplified by PCR. Amplified DNAs were purified by QIAGEN PCR purification kit and sequenced by MWG Biotech (www.mwgdna.com). CAN1 spectra obtained in four strains were compared using several statistical techniques. A Monte Carlo modification of the Pearson χ2 test of spectra homogeneity [69] was used to compare 2 x N tables (two mutation spectra, N≥2). Small probability values (P≤0.05) indicate a significant difference between two spectra. Calculations were done using the program COLLAPSE [70].

Purification of Pol ε, Pol2/Dpb2, and Pol2/Dpb2 exo- complexes

All purification steps were carried out as described in [32].

3′→5′exonuclease processivity and primer extension assay

We used primer 3NY (5′-AGGTCACGATGCGGCATAGCCTGCATTGATCGCACGATGATCAGCGGACTGCTTACC) annealed to the template 19wt (3′-TCCAGTGCTACGCCGTATCGGACGTAACTAGCGTGCTACTAGTCGCCTGACGAATGGACAGTGCCATTGTCACTG) as a substrate for the exonuclease reaction. The primer (8 µM) was labeled with 40 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP in a 20-µl reaction with 10 U T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) for 1 h. The reaction was stopped with EDTA and labeled products were purified through PAGE. The end-labeled primer was annealed to the template at 1.5 : 1 ratio for a 5 minute incubation at 80°C followed by slow cooling to room temperature. For the exonuclease assay 0.5 nM substrate was incubated with 0.1 nM Pol ε or 0.5 nM Pol2/Dpb2 complex in a 65 µl reaction mixture (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8; 1 mM DTT; 0.2 mg/ml Ac-BSA; 8 mM MgCl2; 125 mM NaAc). Fifteen µl aliquots were taken at the indicated time points and were mixed with 8 µl stop solution (80% formamide; 50 mM EDTA; 1 mM bromophenol blue). Before loading the reactions on a 12% polyacrylamide-urea gel, the primer-templates were denatured at 99° C for 4 min and then cooled on ice. The intensity of bands corresponding to different exonuclease products was quantified using phosphoimager plates and the ImageQuant software package supplied with a Typhoon 9400 phosphoimager (Amersham Biosciences).

For primer extension assay a [γ-32P]ATP –labeled (as described previously) 50-mer oligonucleotide was annealed to the pBluescript II SK(+) ssDNA in a ratio of 1∶1.5. For the DNA synthesis processivity assay, the substrate (14 nM) was incubated with the four-subunit Pol ε (0.35 nM) or Pol2/Dpb2 complex (0.7 nM) in a reaction mixture (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8; 1 mM DTT; 0.2 mg/ml Ac-BSA; 8 mM MgCl2; 125 mM NaAc; 100 µM dNTP). Because the loading efficiency of the Pol2/Dpb2 complex on DNA was compromised we used a two and five-fold higher concentration of the Pol2/Dpb2 complex, compared to the full-subunit Pol ε, in the primer-extension assay and exonuclease assay, respectively. The conditions were empirically determined to meet single-hit kinetics, i.e. where a polymerase molecule never re-associated with a previously extended primer.

In the primer-extension assay, the termination probability at position N at each primer/template was calculated by dividing the intensity of the band N by the intensity of all bands ≥ N. In the exonuclease processivity assay, the termination probability at position N at each primer/template was calculated by dividing the intensity of the band N by the intensity of all bands ≤ N [71].

Assay to measure polymerase fidelity in vitro

DNA synthesis fidelity was measured using the bacteriophage M13mp2 forward mutation assay described previously [39], [40]. Briefly, double-stranded M13mp2 DNA with a 407-nucleotide single-stranded region containing a portion of the lacZ gene was used as a substrate for in vitro DNA synthesis. Reactions mixtures contained ∼1.5 nM DNA template, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 100 µg/ml BSA, 10% glycerol, 250 µM dNTPs and 14 nM wild type or exonuclease-deficient 2-subunit Pol ε. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Aliquots of the reactions were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm complete gap-filling, and another aliquot of DNA was introduced into E.coli to score the frequency of light blue and colorless plaques reflecting errors made during in vitro DNA synthesis. Single stranded DNA was isolated from independent mutant M13 plaques and the lacZ gene was sequenced. Error rates (ER) for individual types of mutation were calculated according to the following equation: ER = [(Ni/N)×MF]/(D×0.6) where Ni is the number of mutations of a particular type, N is the total number of mutants analyzed, MF is frequency of lacZ mutants, D is the number of detectable sites for the particular type of mutation, and 0.6 is the probability of expressing a mutant lacZ allele in E. coli.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BebenekK

KunkelTA

2004 Functions of DNA polymerases. Adv Protein Chem 69 137 165

2. GargP

BurgersPM

2005 DNA polymerases that propagate the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 40 115 128

3. JinYH

ObertR

BurgersPM

KunkelTA

ResnickMA

2001 The 3′–>5′ exonuclease of DNA polymerase delta can substitute for the 5′ flap endonuclease Rad27/Fen1 in processing Okazaki fragments and preventing genome instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 5122 5127

4. JinYH

AyyagariR

ResnickMA

GordeninDA

BurgersPM

2003 Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. II. Cooperation between the polymerase and 3′-5′-exonuclease activities of Pol delta in the creation of a ligatable nick. J Biol Chem 278 1626 1633

5. GargP

StithCM

SabouriN

JohanssonE

BurgersPM

2004 Idling by DNA polymerase delta maintains a ligatable nick during lagging-strand DNA replication. Genes Dev 18 2764 2773

6. Nick McElhinnySA

GordeninDA

StithCM

BurgersPM

KunkelTA

2008 Division of labor at the eukaryotic replication fork. Mol Cell 30 137 144

7. PursellZF

IsozI

LundstromEB

JohanssonE

KunkelTA

2007 Yeast DNA polymerase epsilon participates in leading-strand DNA replication. Science 317 127 130

8. ShcherbakovaPV

PavlovYI

1996 3′–>5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerases epsilon and delta correct base analog induced DNA replication errors on opposite DNA strands in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 142 717 726

9. MorrisonA

SuginoA

1994 The 3′–>5′ exonucleases of both DNA polymerases delta and epsilon participate in correcting errors of DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet 242 289 296

10. KarthikeyanR

VonarxEJ

StraffonAF

SimonM

FayeG

2000 Evidence from mutational specificity studies that yeast DNA polymerases delta and epsilon replicate different DNA strands at an intracellular replication fork. J Mol Biol 299 405 419

11. PavlovYI

FrahmC

Nick McElhinnySA

NiimiA

SuzukiM

2006 Evidence that errors made by DNA polymerase alpha are corrected by DNA polymerase delta. Curr Biol 16 202 207

12. PavlovYI

ShcherbakovaPV

2010 DNA polymerases at the eukaryotic fork-20 years later. Mutat Res 685 45 53

13. KunkelTA

BurgersPM

2008 Dividing the workload at a eukaryotic replication fork. Trends Cell Biol 18 521 527

14. BurgersPM

2008 Polymerase dynamics at the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. J Biol Chem 284 4041 4045

15. BudzowskaM

KanaarR

2009 Mechanisms of dealing with DNA damage-induced replication problems. Cell Biochem Biophys 53 17 31

16. LopesM

FoianiM

SogoJM

2006 Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol Cell 21 15 27

17. KarrasGI

JentschS

2010 The RAD6 DNA damage tolerance pathway operates uncoupled from the replication fork and is functional beyond S phase. Cell 141 255 267

18. DaigakuY

DaviesAA

UlrichHD

2010 Ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is separable from genome replication. Nature 465 951 955

19. PomerantzRT

O'DonnellM

2008 The replisome uses mRNA as a primer after colliding with RNA polymerase. Nature 456 762 766

20. ChilkovaO

JonssonBH

JohanssonE

2003 The quaternary structure of DNA polymerase epsilon from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 278 14082 14086

21. ArakiH

HamatakeRK

JohnstonLH

SuginoA

1991 DPB2, the gene encoding DNA polymerase II subunit B, is required for chromosome replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88 4601 4605

22. FengW

Rodriguez-MenocalL

TolunG

D'UrsoG

2003 Schizosacchromyces pombe Dpb2 binds to origin DNA early in S phase and is required for chromosomal DNA replication. Mol Biol Cell 14 3427 3436

23. KestiT

McDonaldWH

YatesJRIII

WittenbergC

2004 Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the DNA polymerase epsilon subunit, Dpb2, by the Cdc28 cyclin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 279 14245 14255

24. JaszczurM

FlisK

RudzkaJ

KraszewskaJ

BuddME

2008 Dpb2p, a noncatalytic subunit of DNA polymerase epsilon, contributes to the fidelity of DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178 633 647

25. JaszczurM

RudzkaJ

KraszewskaJ

FlisK

PolaczekP

2009 Defective interaction between Pol2p and Dpb2p, subunits of DNA polymerase epsilon, contributes to a mutator phenotype in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat Res 669 27 35

26. ArakiH

HamatakeRK

MorrisonA

JohnsonAL

JohnstonLH

1991 Cloning DPB3, the gene encoding the third subunit of DNA polymerase II of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 19 4867 4872

27. NorthamMR

GargP

BaitinDM

BurgersPM

ShcherbakovaPV

2006 A novel function of DNA polymerase zeta regulated by PCNA. EMBO J 25 4316 4325

28. LiY

PursellZF

LinnS

2000 Identification and cloning of two histone fold motif-containing subunits of HeLa DNA polymerase epsilon. J Biol Chem 275 31554

29. TsubotaT

MakiS

KubotaH

SuginoA

MakiH

2003 Double-stranded DNA binding properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon and of the Dpb3p-Dpb4p subassembly. Genes Cells 8 873 888

30. IidaT

ArakiH

2004 Noncompetitive counteractions of DNA polymerase epsilon and ISW2/yCHRAC for epigenetic inheritance of telomere position effect in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 24 217 227

31. TackettAJ

DilworthDJ

DaveyMJ

O'DonnellM

AitchisonJD

2005 Proteomic and genomic characterization of chromatin complexes at a boundary. J Cell Biol 169 35 47

32. AsturiasFJ

CheungIK

SabouriN

ChilkovaO

WepploD

2006 Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13 35 43

33. ShcherbakovaPV

KunkelTA

1999 Mutator phenotypes conferred by MLH1 overexpression and by heterozygosity for mlh1 mutations. Mol Cell Biol 19 3177 3183

34. TranHT

KeenJD

KrickerM

ResnickMA

GordeninDA

1997 Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol Cell Biol 17 2859 2865

35. TranHT

GordeninDA

ResnickMA

1999 The 3′–>5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerases delta and epsilon and the 5′–>3′ exonuclease Exo1 have major roles in postreplication mutation avoidance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 19 2000 2007

36. KirchnerJM

TranH

ResnickMA

2000 A DNA polymerase epsilon mutant that specifically causes +1 frameshift mutations within homonucleotide runs in yeast. Genetics 155 1623 1632

37. DangW

KagalwalaMN

BartholomewB

2007 The Dpb4 subunit of ISW2 is anchored to extranucleosomal DNA. J Biol Chem 282 19418 19425

38. GangarajuVK

PrasadP

SrourA

KagalwalaMN

BartholomewB

2009 Conformational changes associated with template commitment in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling by ISW2. Mol Cell 35 58 69

39. BebenekK

KunkelTA

1995 Analyzing fidelity of DNA polymerases. Methods Enzymol 262 217 232

40. ShcherbakovaPV

PavlovYI

ChilkovaO

RogozinIB

JohanssonE

2003 Unique error signature of the four-subunit yeast DNA polymerase epsilon. J Biol Chem 278 43770 43780

41. LawrenceCW

2004 Cellular functions of DNA polymerase zeta and Rev1 protein. Adv Protein Chem 69 167 203

42. NorthamMR

RobinsonHA

KochenovaOV

ShcherbakovaPV

2009 Participation of DNA Polymerase {zeta} in Replication of Undamaged DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 184 27 42

43. ZhongX

GargP

StithCM

Nick McElhinnySA

KisslingGE

2006 The fidelity of DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase zeta alone and with accessory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 34 4731 4742

44. PavlovYI

ShcherbakovaPV

KunkelTA

2001 In vivo consequences of putative active site mutations in yeast DNA polymerases alpha, epsilon, delta, and zeta. Genetics 159 47 64

45. HarfeBD

Jinks-RobertsonS

2000 DNA mismatch repair and genetic instability. Annu Rev Genet 34 359 399

46. TranHT

DegtyarevaNP

GordeninDA

ResnickMA

1999 Genetic factors affecting the impact of DNA polymerase delta proofreading activity on mutation avoidance in yeast. Genetics 152 47 59

47. HuangME

RioAG

GalibertMD

GalibertF

2002 Pol32, a subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta, suppresses genomic deletions and is involved in the mutagenic bypass pathway. Genetics 160 1409 1422

48. ChilkovaO

StenlundP

IsozI

StithCM

GrabowskiP

2007 The eukaryotic leading and lagging strand DNA polymerases are loaded onto primer-ends via separate mechanisms but have comparable processivity in the presence of PCNA. Nucleic Acids Res 35 6588 6597

49. KokoskaRJ

StefanovicL

DeMaiJ

PetesTD

2000 Increased rates of genomic deletions generated by mutations in the yeast gene encoding DNA polymerase delta or by decreases in the cellular levels of DNA polymerase delta. Mol Cell Biol 20 7490 7504

50. XieY

CounterC

AlaniE

1999 Characterization of the repeat-tract instability and mutator phenotypes conferred by a Tn3 insertion in RFC1, the large subunit of the yeast clamp loader. Genetics 151 499 509

51. NiimiA

LimsirichaikulS

YoshidaS

IwaiS

MasutaniC

2004 Palm mutants in DNA polymerases alpha and eta alter DNA replication fidelity and translesion activity. Mol Cell Biol 24 2734 2746

52. ChenC

UmezuK

KolodnerRD

1998 Chromosomal rearrangements occur in S. cerevisiae rfa1 mutator mutants due to mutagenic lesions processed by double-strand-break repair. Mol Cell 2 9 22

53. YangY

SterlingJ

StoriciF

ResnickMA

GordeninDA

2008 Hypermutability of damaged single-strand DNA formed at double-strand breaks and uncapped telomeres in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 4 e1000264 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000264

54. JinYH

GargP

StithCM

Al-RefaiH

SterlingJF

2005 The multiple biological roles of the 3′–>5′ exonuclease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta require switching between the polymerase and exonuclease domains. Mol Cell Biol 25 461 471

55. SwanMK

JohnsonRE

PrakashL

PrakashS

AggarwalAK

2009 Structural basis of high-fidelity DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase delta. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16 979 986

56. GutierrezPJ

WangTS

2003 Genomic instability induced by mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae POL1. Genetics 165 65 81

57. TranHT

GordeninDA

ResnickMA

1996 The prevention of repeat-associated deletions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mismatch repair depends on size and origin of deletions. Genetics 143 1579 1587

58. KunkelTA

ErieDA

2005 DNA mismatch repair. Annu Rev Biochem 74 681 710

59. MojasN

LopesM

JiricnyJ

2007 Mismatch repair-dependent processing of methylation damage gives rise to persistent single-stranded gaps in newly replicated DNA. Genes Dev 21 3342 3355

60. LehnerK

Jinks-RobertsonS

2009 The mismatch repair system promotes DNA polymerase zeta-dependent translesion synthesis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 5749 5754

61. DelbosF

AoufouchiS

FailiA

WeillJC

ReynaudCA

2007 DNA polymerase eta is the sole contributor of A/T modifications during immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J Exp Med 204 17 23

62. AlbertsonTM

OgawaM

BugniJM

HaysLE

ChenY

2009 DNA polymerase {varepsilon} and {delta} proofreading suppress discrete mutator and cancer phenotypes in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

63. GoldsteinAL

McCuskerJH

1999 Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15 1541 1553

64. PavlovYI

MakiS

MakiH

KunkelTA

2004 Evidence for interplay among yeast replicative DNA polymerases alpha, delta and epsilon from studies of exonuclease and polymerase active site mutations. BMC Biol 2 11

65. MorrisonA

BellJB

KunkelTA

SuginoA

1991 Eukaryotic DNA polymerase amino acid sequence required for 3′––5′ exonuclease activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88 9473 9477

66. JinYH

ObertR

BurgersPM

KunkelTA

ResnickMA

2001 The 3′–>5′ exonuclease of DNA polymerase delta can substitute for the 5′ flap endonuclease Rad27/Fen1 in processing Okazaki fragments and preventing genome instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 5122 5127

67. PavlovYI

MianIM

KunkelTA

2003 Evidence for preferential mismatch repair of lagging strand DNA replication errors in yeast. Curr Biol 13 744 748

68. ShcherbakovaPV

NoskovVN

PshenichnovMR

PavlovYI

1996 Base analog 6-N-hydroxylaminopurine mutagenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by replicative DNA polymerases. Mutat Res 369 33 44

69. AdamsWT

SkopekTR

1987 Statistical test for the comparison of samples from mutational spectra. J Mol Biol 194 391 396

70. Khromov-BorisovNN

RogozinIB

Pegas HenriquesJA

de SerresFJ

1999 Similarity pattern analysis in mutational distributions. Mutat Res 430 55 74

71. KokoskaRJ

McCullochSD

KunkelTA

2003 The efficiency and specificity of apurinic/apyrimidinic site bypass by human DNA polymerase eta and Sulfolobus solfataricus Dpo4. J Biol Chem 278 50537 50545

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 11

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Cortical Bone Mineral Density Unravels Allelic Heterogeneity at the Locus and Potential Pleiotropic Effects on Bone

- Beyond QTL Cloning

- An Evolutionary Framework for Association Testing in Resequencing Studies

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-p13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A

- The Functional Interplay between Protein Kinase CK2 and CCA1 Transcriptional Activity Is Essential for Clock Temperature Compensation in Arabidopsis

- Endogenous Viral Elements in Animal Genomes

- Analysis of the 10q11 Cancer Risk Locus Implicates and in Human Prostate Tumorigenesis

- DNA Methylation and Normal Chromosome Behavior in Neurospora Depend on Five Components of a Histone Methyltransferase Complex, DCDC

- Sarcomere Formation Occurs by the Assembly of Multiple Latent Protein Complexes

- Genetic Basis of Growth Adaptation of after Deletion of , a Major Metabolic Gene

- Nomadic Enhancers: Tissue-Specific -Regulatory Elements of Have Divergent Genomic Positions among Species

- The Parental Non-Equivalence of Imprinting Control Regions during Mammalian Development and Evolution

- CTCF-Dependent Chromatin Bias Constitutes Transient Epigenetic Memory of the Mother at the Imprinting Control Region in Prospermatogonia

- Systematic Dissection and Trajectory-Scanning Mutagenesis of the Molecular Interface That Ensures Specificity of Two-Component Signaling Pathways

- Nucleolin Is Required for DNA Methylation State and the Expression of rRNA Gene Variants in

- The Complex Genetic Architecture of the Metabolome

- ATM Limits Incorrect End Utilization during Non-Homologous End Joining of Multiple Chromosome Breaks

- Mutation Disrupts Synaptonemal Complex Formation, Recombination, and Chromosome Segregation in Mammalian Meiosis

- Mismatch Repair–Independent Increase in Spontaneous Mutagenesis in Yeast Lacking Non-Essential Subunits of DNA Polymerase ε

- The Kinesin-3 Motor UNC-104/KIF1A Is Degraded upon Loss of Specific Binding to Cargo

- Epigenetic Silencing of Spermatocyte-Specific and Neuronal Genes by SUMO Modification of the Transcription Factor Sp3

- A Coastal Cline in Sodium Accumulation in Is Driven by Natural Variation of the Sodium Transporter AtHKT1;1

- Cyclin B3 Is Required for Multiple Mitotic Processes Including Alleviation of a Spindle Checkpoint–Dependent Block in Anaphase Chromosome Segregation

- Altered DNA Methylation in Leukocytes with Trisomy 21

- Human-Specific Evolution and Adaptation Led to Major Qualitative Differences in the Variable Receptors of Human and Chimpanzee Natural Killer Cells

- Leptotene/Zygotene Chromosome Movement Via the SUN/KASH Protein Bridge in

- RACK-1 Acts with Rac GTPase Signaling and UNC-115/abLIM in Axon Pathfinding and Cell Migration

- Genome-Wide Effects of Long-Term Divergent Selection

- Endless Forms Most Viral

- Conflict between Noise and Plasticity in Yeast

- Essential Functions of the Histone Demethylase Lid

- The Transcriptional Regulator Rok Binds A+T-Rich DNA and Is Involved in Repression of a Mobile Genetic Element in

- The Cellular Robustness by Genetic Redundancy in Budding Yeast

- Localization of a Guanylyl Cyclase to Chemosensory Cilia Requires the Novel Ciliary MYND Domain Protein DAF-25

- A Buoyancy-Based Screen of Drosophila Larvae for Fat-Storage Mutants Reveals a Role for in Coupling Fat Storage to Nutrient Availability

- A Functional Genomics Approach Identifies Candidate Effectors from the Aphid Species (Green Peach Aphid)

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-p13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A

- Analysis of the 10q11 Cancer Risk Locus Implicates and in Human Prostate Tumorigenesis

- The Parental Non-Equivalence of Imprinting Control Regions during Mammalian Development and Evolution

- Genome-Wide Effects of Long-Term Divergent Selection

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání