-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaHIV Restriction by APOBEC3 in Humanized Mice

Innate immune restriction factors represent important specialized barriers to zoonotic transmission of viruses. Significant consideration has been given to their possible use for therapeutic benefit. The apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide 3 (APOBEC3) family of cytidine deaminases are potent immune defense molecules capable of efficiently restricting endogenous retroelements as well as a broad range of viruses including Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Human Papilloma virus (HPV), and Human T Cell Leukemia virus (HTLV). The best characterized members of this family are APOBEC3G (A3G) and APOBEC3F (A3F) and their restriction of HIV. HIV has evolved to counteract these powerful restriction factors by encoding an accessory gene designated viral infectivity factor (vif). Here we demonstrate that APOBEC3 efficiently restricts CCR5-tropic HIV in the absence of Vif. However, our results also show that CXCR4-tropic HIV can escape from APOBEC3 restriction and replicate in vivo independent of Vif. Molecular analysis identified thymocytes as cells with reduced A3G and A3F expression. Direct injection of vif-defective HIV into the thymus resulted in viral replication and dissemination detected by plasma viral load analysis; however, vif-defective viruses remained sensitive to APOBEC3 restriction as extensive G to A mutation was observed in proviral DNA recovered from other organs. Remarkably, HIV replication persisted despite the inability of HIV to develop resistance to APOBEC3 in the absence of Vif. Our results provide novel insight into a highly specific subset of cells that potentially circumvent the action of APOBEC3; however our results also demonstrate the massive inactivation of CCR5-tropic HIV in the absence of Vif.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003242

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003242Summary

Innate immune restriction factors represent important specialized barriers to zoonotic transmission of viruses. Significant consideration has been given to their possible use for therapeutic benefit. The apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide 3 (APOBEC3) family of cytidine deaminases are potent immune defense molecules capable of efficiently restricting endogenous retroelements as well as a broad range of viruses including Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Human Papilloma virus (HPV), and Human T Cell Leukemia virus (HTLV). The best characterized members of this family are APOBEC3G (A3G) and APOBEC3F (A3F) and their restriction of HIV. HIV has evolved to counteract these powerful restriction factors by encoding an accessory gene designated viral infectivity factor (vif). Here we demonstrate that APOBEC3 efficiently restricts CCR5-tropic HIV in the absence of Vif. However, our results also show that CXCR4-tropic HIV can escape from APOBEC3 restriction and replicate in vivo independent of Vif. Molecular analysis identified thymocytes as cells with reduced A3G and A3F expression. Direct injection of vif-defective HIV into the thymus resulted in viral replication and dissemination detected by plasma viral load analysis; however, vif-defective viruses remained sensitive to APOBEC3 restriction as extensive G to A mutation was observed in proviral DNA recovered from other organs. Remarkably, HIV replication persisted despite the inability of HIV to develop resistance to APOBEC3 in the absence of Vif. Our results provide novel insight into a highly specific subset of cells that potentially circumvent the action of APOBEC3; however our results also demonstrate the massive inactivation of CCR5-tropic HIV in the absence of Vif.

Introduction

Innate immune restriction factors embody specialized barriers to zoonotic transmission of viruses. Substantial consideration has been given to their potential use for therapeutic benefit [1], [2]. The apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide 3 (APOBEC3) family of cytidine deaminases are potent innate immune defense factors capable of efficiently restricting endogenous retroelements as well as a diverse range of viruses including Hepatitis B virus, Human Immunodeficiency virus, Human T Cell Leukemia virus, TT virus, and Human Papilloma virus [3]–[8].

The best-characterized APOBEC3 family members are the immune defense molecules APOBEC3G (A3G) and APOBEC3F (A3F) and their lethal restriction of HIV [5], [9]. HIV has evolved to counteract these powerful restriction factors by encoding an accessory gene designated viral infectivity factor (vif). In vitro studies have elegantly shown that in the absence of Vif, A3G and A3F are encapsidated into nascent virions and deaminate cytosines in the minus strand of HIV DNA during reverse transcription [10]–[12]. APOBEC3 deamination of cytosines in the minus strand of the viral genome occurs at both CC and TC dinucleotide sites, resulting in GG to AG as well as GA to AA mutations in the coding strand of the viral genome [10], [11], [13], [14]. APOBEC3 induced G to A mutations at GG dinucleotide sites are exclusively the result of A3G deamination, while mutations occurring at GA sites can be caused by multiple APOBEC3 proteins including both A3F and A3G [10], [15]. While studies have demonstrated the deleterious effects of G to A hypermutation of the HIV genome [10], [16]–[18], a recent in vitro study showed variable levels of A3G induced G to A mutations suggesting that A3G may contribute to viral diversity [19].

In this study, we use humanized mice for the in vivo study of HIV in the context of a human immune system. Both NSG-hu and NSG BLT mice are systemically reconstituted with multiple lineages of hematopoietic cells including T cells, B cells, and myeloid cells following transplantation with CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [20], [21]. Additionally, BLT humanized mice are implanted with human liver and thymic tissue under the kidney capsule prior to the transplant of autologous CD34+ cells which results in the development of a bona fide human thymus for T cell development [21]. Like any other model for HIV/AIDS research humanized mice have several strengths and limitations that have to be taken into consideration in the development of experimental plan. Two recent review articles cover this area in significant detail [22], [23]. Despite their limitations humanized mouse models have previously been used for the study of HIV transmission, pathogenesis, prevention, therapy and latency/eradication [20], [24]–[28]. Here we first demonstrate the highly effective inactivation of CCR5-tropic HIV-1 by APOBEC3 when unobstructed by a functioning vif in vivo after intravenous infection. Secondly, we demonstrate that if injected directly into the thymus, vif-defective viruses can replicate escaping absolute APOBEC3 restriction.

Results

Mutations in vif do not affect virus replication in the absence of APOBEC3

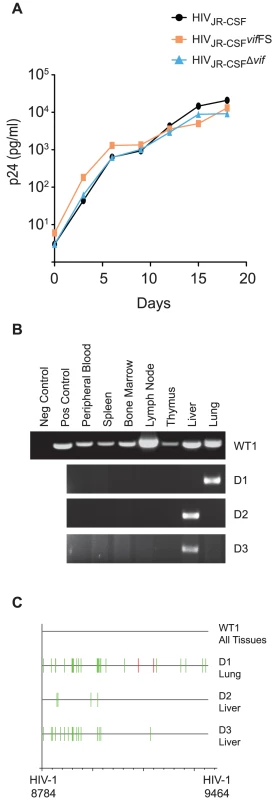

To confirm that the mutations disrupting vif do not have a detrimental effect on the replicative capacity of HIV-1JR-CSF, we generated a CCR5 expressing permissive cell line (CEM-SS CCR5) and infected them with wild-type HIV-1JR-CSF or isogenic viruses containing either an irreparable deletion in vif (HIVJR-CSFΔvif) or a one base insertion in vif (HIVJR-CSFvifFS). Replication of both vif-defective viruses was equal to that of wild-type in permissive cells, confirming that the disruption of vif did not have a deleterious effect on HIV-1 in the absence of APOBEC3 (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. Human APOBEC3 rapidly restricts vif-deleted HIV-1JR-CSF in vivo.

(A) Replication of HIVJR-CSF, HIVJR-CSFΔvif, and HIVJR-CSFvifFS in CEM-SS cells expressing CCR5 (CEM-SS CCR5). Culture supernatant was assayed for p24Gag by ELISA at three day intervals to determine the replication kinetics of the mutant viruses. (B) Nested PCR amplification of viral DNA from the tissues obtained one week post-exposure from a representative NSG-hu mouse infected with 9×104 TCIU of wild-type HIV-1JR-CSF (WT1) or from three mice infected with 3.6×105 TCIU of HIVJR-CSFΔvif (indicated as D1–3). (C) Highlighter sequence analysis of 7 wild-type and 3 Δvif HIV DNA sequences. Amplified viral DNA from panel A showed no APOBEC3 induced mutations in HIVJR-CSF (WT1 all sequence from tissues is shown together). In contrast, viral DNA from all positive tissues obtained from HIVJR-CSFΔvif infected mice had G to A (green lines) and/or C to T mutations (red lines). HIV-1JR-CSF nucleotide numbers are indicated at the bottom. vif-deleted CCR5 tropic HIV-1 administered intravenously is rapidly restricted by APOBEC3 in vivo

To assess the in vivo effectiveness of APOBEC3 restriction of HIV, we intravenously infected NSG-hu mice with wild-type HIV-1JR-CSF (a T-cell CCR5-tropic primary isolate) or HIVJR-CSFΔvif. As early as one week after intravenous infection, widespread replication of wild-type virus was detected as HIV DNA was amplified from every tissue analyzed (Figure 1B). In contrast the vif-defective virus did not sustain replication in humanized mice; as viral DNA was sparsely present (Figure 1B). Notably, HIVJR-CSFΔvif DNA could only be amplified from one organ from each infected mouse suggesting that an extremely low number of infected cells were present. Analysis of the viral DNA sequence from the animals revealed that HIV DNA from mice infected with wild-type virus had no mutations, whereas viral DNA from the HIVJR-CSFΔvif infected mice had numerous G to A mutations consistent with APOBEC3 induced restriction (Figure 1C). The limited number of tissues with cells harboring G to A mutated HIVJR-CSFΔvif DNA one week after exposure suggests that APOBEC3 restriction of vif-defective HIV occurs rapidly in vivo.

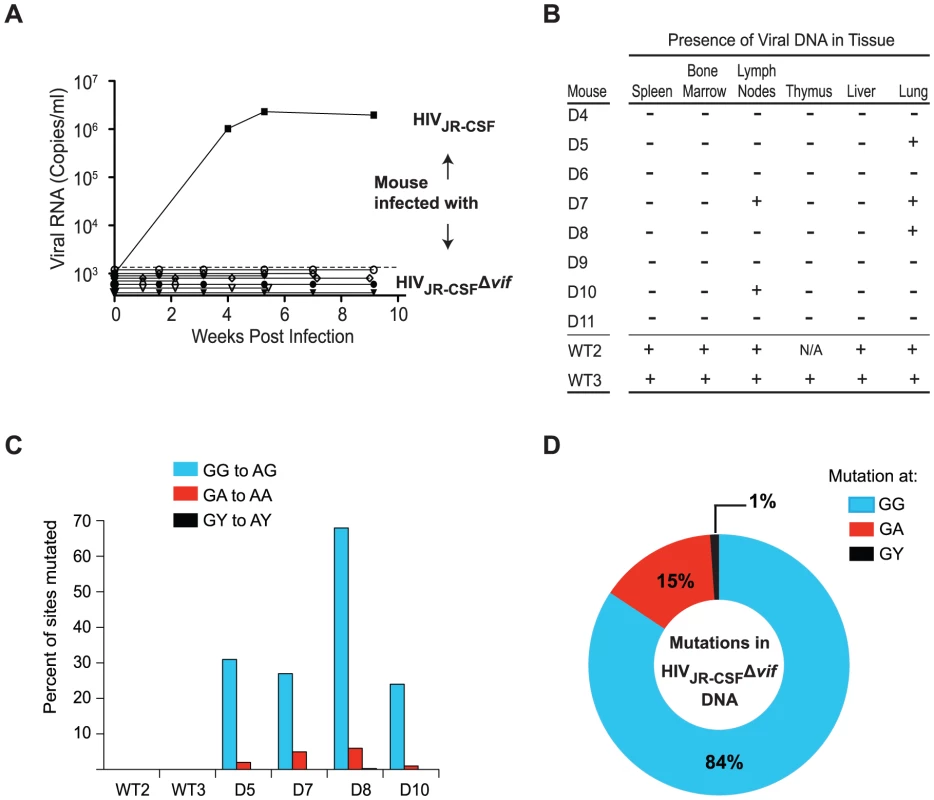

APOBEC3 restriction of CCR5 tropic in the absence of vif

While evidence of APOBEC3 restriction of vif-deficient HIV is observed early after infection, we next determined whether HIVJR-CSFΔvif could develop resistance to APOBEC3 and replicate systemically. To address this, we infected humanized mice (n = 8) intravenously with HIVJR-CSFΔvif and monitored them for plasma viral load. Longitudinal analysis demonstrated that HIVJR-CSFΔvif restriction by APOBEC3 is absolute, as no viral RNA was present in the plasma of the mice at any time point in contrast to infection with wild-type HIVJR-CSF (Figure 2A). No revertants or complementary changes arose that restored the ability of HIVJR-CSFΔvif to replicate. In contrast to the widespread presence of viral DNA in all tissues analyzed after wild-type HIV infection, the extremely limited replication of HIVJR-CSFΔvif was confirmed by the absence of HIV DNA in tissues obtained from 4/8 infected mice, and the presence of lethally mutated viral DNA in only a few tissues of the other four animals (Figure 2B). To determine the extent of APOBEC3 hypermutation in the HIVJR-CSFΔvif provirus, we analyzed the sequences for G to A mutations at GG, GA and GY dinucleotide sites which are the targets of the APOBEC3 proteins. We found that 25–65% of the GG sites had been mutated with additional (albeit fewer) mutations present at GA sites, demonstrating extensive APOBEC3 hypermutation to lethally restrict HIVJR-CSFΔvif (Figure 2C). Analysis of the mutational profile in the HIVJR-CSFΔvif DNA from the mice showed that 84% of all the G to A mutations occurred at GG dinucleotide sites whereas only 15% of mutations were present at GA sites and only 1% occurred at GY sites (Figure 2D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that HIVJR-CSFΔvif is unable to overcome the loss of Vif and is lethally restricted by APOBEC3 in vivo.

Fig. 2. vif-deleted HIV-1JR-CSF does not overcome APOBEC3 restriction in vivo.

(A) Longitudinal analysis of plasma viral load in humanized mice intravenously infected with 9×104 TCIU of wild-type HIV-1JR-CSF or 3.6×105 TCIU of HIVJR-CSFΔvif. (B) Detection of HIV DNA (+) by nested PCR from the tissues of humanized mice in panel A. Negative tissues (−) yielded no amplified viral DNA using two independent nested PCR primer sets targeting separate regions of the viral genome. N/A = not analyzed. (C) Percentage of putative APOBEC3 mutation sites (GG, GA, GY) that were mutated in 17 viral DNA sequences amplified from the tissues of infected mice. Viral DNA from mice infected with HIVJR-CSFΔvif had 25%–65% of GG sites mutated. (D) G to A mutational profile of all viral DNA from mice infected with HIVJR-CSFΔvif. Percentages indicate the proportion of G to A mutations occurring at GG (blue), GA (red), or GY (black) sites. D4-D8, WT2-WT3, NSG-hu mice. D9-D11, NSG-BLT mice. Human APOBEC3 exerts a strong selective pressure on HIV-1 in vivo

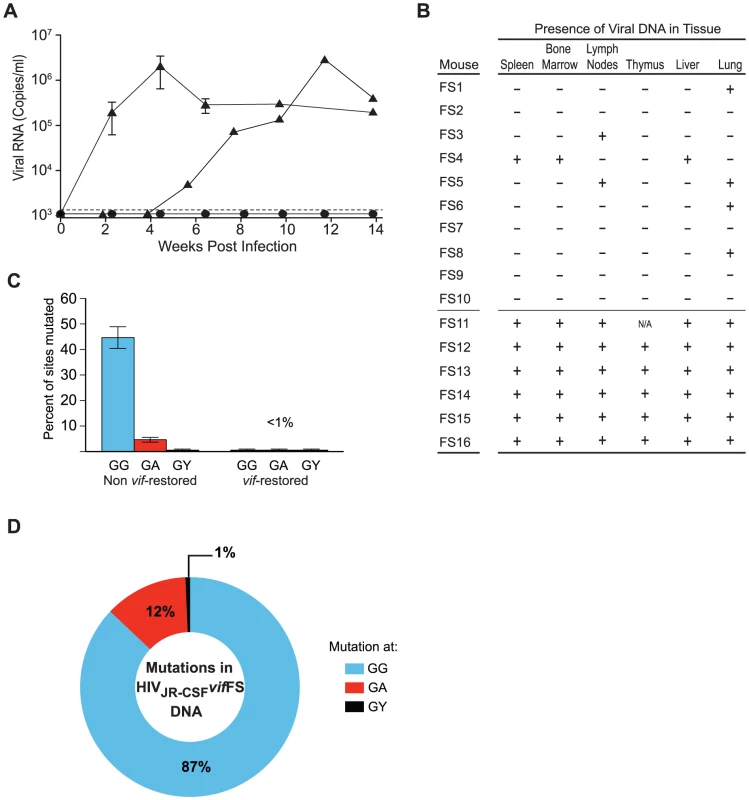

To evaluate the selective pressure exerted by APOBEC3 on HIV in vivo, we used a mutant isogenic virus containing a one base insertion in vif (HIVJR-CSFvifFS) to intravenously infect 16 humanized mice representing 7 different human donors. Consistent with our previous results, in 10/16 mice intravenously infected with HIVJR-CSFvifFS there was no evidence of virus replication as determined by the absence of viral RNA in the plasma (Figure 3A). However, in the remaining six mice the virus was able to replicate to levels similar to those observed with the wild-type virus (Figure 3A). One salient aspect noted was the almost complete absence of APOBEC3 mutations in viral RNA samples obtained from the plasma from these six mice. Molecular analysis of viral sequences from the peripheral blood from these mice demonstrated that in all six cases a one-nucleotide deletion had occurred that fully restored the vif open reading frame (ORF) highlighting the extreme selective pressure APOBEC3 exerts on HIV in vivo to restore Vif activity or be lethally mutated. Two important issues that should be noted are 1) the virus used for these experiments was generated via transient transfection of 293T cells creating a uniform inoculum and 2) that this repair mutation occurring in vivo is not at a putative APOBEC3 site and therefore it is most likely is a result of a mutation occurring during reverse transcription.

Fig. 3. Human APOBEC3 exerts a strong selective pressure on HIV-1JR-CSF containing a frameshift in vif.

(A) Plasma viral load analysis in humanized mice intravenously infected with 9×104 or 3.6×105 TCIU of HIVJR-CSFvifFS. Viral RNA was not detected in the plasma (circles, n = 10) unless the vif ORF is restored (triangles, n = 6). The appearance of plasma viremia was delayed by 4 weeks in one of these mice. (B) Detection of HIV DNA (+) by nested PCR from the tissues of humanized mice intravenously infected with HIVJR-CSFvifFS. Negative tissues (−) yielded no amplified viral DNA using two independent nested PCR primer sets targeting separate regions of the viral genome. Viral DNA is sparsely present in tissues from mice where vif was not restored (indicated as FS1–10). In contrast, all tissues analyzed from the six mice where vif was restored had viral DNA present (FS11–16). N/A = not analyzed. (C) Percentage of putative APOBEC3 mutation sites (GG, GA, GY) that were mutated in 76 viral DNA sequences amplified from the tissues of HIVJR-CSFvifFS infected mice where vif was not restored (40% of all GG sites mutated) or mice where vif was restored (no hypermutation). Data represent mean +/− SEM. (D) G to A mutational profile of all viral DNA from mice infected with HIVJR-CSFΔvif. Percentages indicate the proportion of G to A mutations occurring at GG (blue), GA (red), or GY (black) sites. FS1–FS9, FS11–FS14, NSG-hu mice. FS10, FS15–FS16 NSG-BLT mice. We then analyzed viral DNA from the tissues of all 16 mice exposed to HIVJR-CSFvifFS. In multiple tissue samples from four of the aviremic mice we found no evidence of HIV DNA. In similar samples from six other aviremic mice only low levels of heavily mutated HIV DNA was present in a few tissues (30–60% of the GG dinucleotide sites mutated) (Figure 3B and 3C). The mutational profile of the viral DNA from these animals again showed a preference for GG sites accounting for 87% of all mutations (Figure 3D). In sharp contrast, in mice where the vif ORF was restored virtually intact viral DNA was present in every tissue analyzed, highlighting the strong selective pressure exerted by APOBEC3 on HIV (Figure 3B and 3C). The lack of G to A mutations in the vif-restored viral genome suggested that the virus had evaded APOBEC3 restriction until restoring vif.

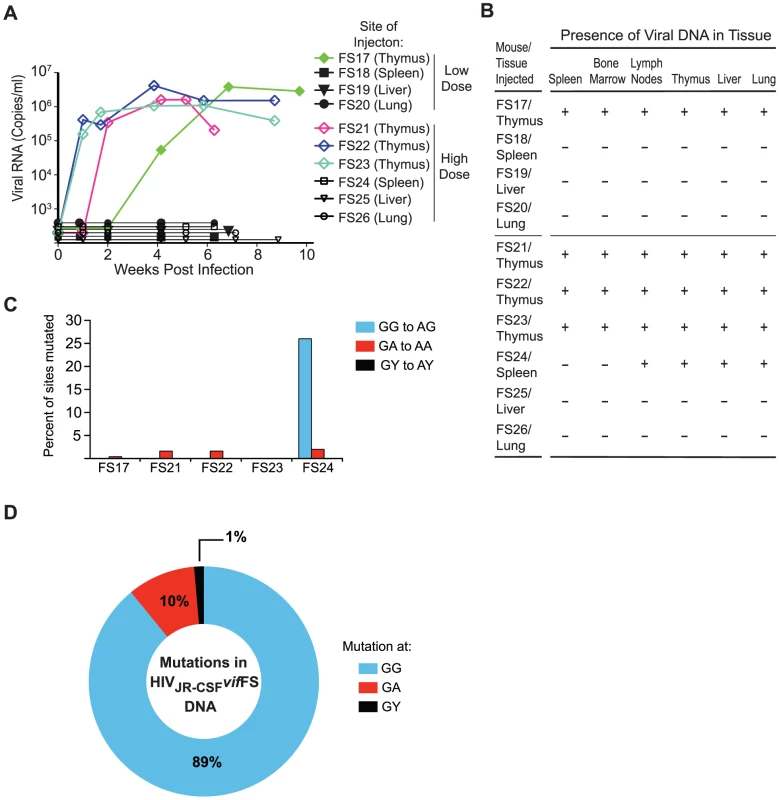

HIV-1JR-CSFvifFS restores vif following direct injection into the thymus

The stochastic nature of vif ORF restoration may reflect its occurrence in a specific anatomical location(s). Therefore we directly injected 9×104 TCIU of HIVJR-CSFvifFS into the spleen, liver, lung or human thymic implant of separate humanized mice. Evidence of viral replication in peripheral blood was exclusively found when HIVJR-CSFvifFS was injected directly into the thymus (Figure 4A). In this case, sequence analysis of vif showed a one base deletion restoring Vif expression. Injection of the virus into the spleen, liver, or lung resulted in absolute restriction with no viremia and no residual viral DNA present in any tissue (Figure 4A and 4B)

Fig. 4. Restoration of vif occurs only following direct virus injection into the thymus.

(A) Longitudinal analysis of plasma viral load in NSG-BLT humanized mice infected with HIVJR-CSFvifFS directly into the human thymic implant, spleen, liver, or lung. Solid symbols represent mice infected with a low dose of virus (9×104 TCIU), open symbols represent the high dose infection (3.6×105 TCIU). (B) Detection of HIV DNA (+) by nested PCR from the tissues of humanized mice in panel A. Negative tissues (−) yielded no amplified viral DNA using two independent nested PCR primer sets targeting separate regions of the viral genome. (C) Percentage of putative APOBEC3 mutation sites (GG, GA, GY) that were mutated in 44 viral DNA sequences amplified from the tissues of mice injected with HIVJR-CSFvifFS. Mice injected into the thymic implant had no GG to AG mutations in any tissue whereas HIV DNA from four tissues of mouse FS24 injected into the spleen is hypermutated. (D) G to A mutational profile of all viral DNA from mouse FS24 which failed to restore the vif ORF. Percentages indicate the proportion of G to A mutations occurring at GG (blue), GA (red), or GY (black) sites. To determine if restoration of the vif ORF following thymic injection was non-random, we increased the virus inoculum four-fold and repeated the infection, using 3.6×105 TCIU of HIVJR-CSFvifFS injected into the same set of tissues. Again evidence of HIV replication was only observed after intrathymic exposure with 3/3 mice that received the virus directly into the thymus becoming viremic (Figure 4A). Strikingly, despite the high virus inoculum injected directly into the spleen, liver, or lung no evidence of virus replication was observed (Figure 4A). When tissues from these animals were analyzed, we found that only one mouse, FS24, had viral DNA present (Figure 4B) and that it had all been lethally mutated by APOBEC3 (Figure 4C and 4D). These results demonstrate that transient HIVJR-CSFvifFS replication and subsequent vif restoration specifically occurs following a direct thymic exposure. Furthermore, the potent antiretroviral activity of APOBEC3 is highlighted by the absolute restriction of HIVJR-CSFvifFS when the virus is injected into other tissues.

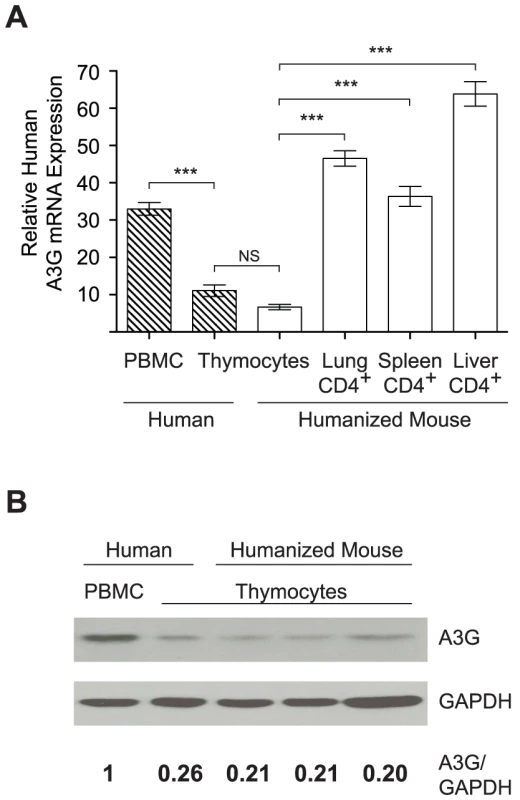

APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F expression is reduced in the thymus

Since the reversion of the vif ORF specifically occurred following injection of the virus into the thymus, we next determined whether A3G and A3F expression was lower in the thymus compared to other tissues. We tested this by comparing A3G and A3F mRNA levels in purified thymocytes (of which >90% are CD4+) with those in CD4+ cells isolated from other tissues in humanized mice. Our results show that thymocytes express 4–8 fold less A3G mRNA and 2.5–3.5 fold less A3F mRNA than human CD4+ cells isolated from the spleen, liver or lung (Figure 5A and Figure S1). Furthermore, no difference in A3G or A3F mRNA expression was found in thymocytes from humanized mice or human thymus. Additionally, A3G in thymocytes was found to be 3–4 fold lower compared to human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) by both mRNA and protein expression (Figure 5A and 5B). These results are consistent with the observation that vif reversion specifically occurs following thymic injection of HIVJR-CSFvifFS and suggests that the thymus may support Vif-independent HIV replication.

Fig. 5. APOBEC3G expression is reduced in the thymus.

(A) Human A3G mRNA levels from human PBMC (n = 7), human thymus (n = 6), NSG-BLT humanized mouse thymus (n = 18), and CD4+ cells from NSG-BLT humanized mouse lung (n = 6), spleen (n = 7), liver (n = 7) were determined using qRT-PCR and normalized to human TATA Box binding protein. Hatched bars represent human cells; open bars represent humanized mouse cells. NS = not significant, *** p<0.01 by one way ANOVA with Bonferroni's posttest. Data represent mean +/− SEM. (B) Immunoblot for human A3G and GAPDH from human PBMC and cells from human and humanized mouse thymus. Numbers represent A3G normalized to GAPDH compared to human PBMC which is set to 1. Based on our observations of reduced A3G and A3F expression in thymocytes and reversion of the vif ORF exclusively occurring with thymic exposure, we considered the possibility that a direct injection of HIVJR-CSFΔvif (the virus containing a non-revertible deletion in vif) into the thymus would result in Vif-independent replication. HIV RNA was transiently observed in the plasma of 2/6 mice following thymic infection with this virus (Figure S2). This low level of replication in some mice is consistent with the results presented above with frame shift containing HIVJR-CSFvifFS (Figure 4A), in which the virus had restored the vif ORF and was able to replicate unimpeded by APOBEC3 after reversion. These results show that recovery of Vif activity is necessary for ongoing replication and viral dissemination by vif-defective HIVJR-CSF.

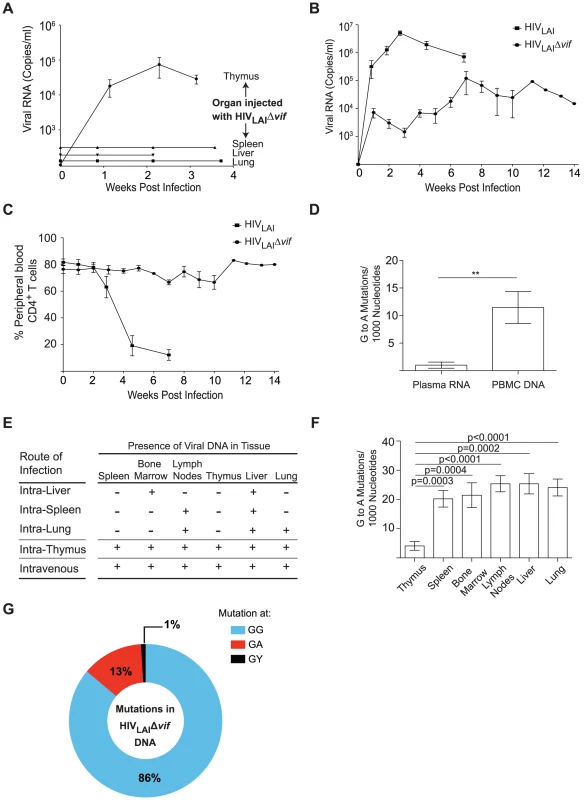

Vif-independent CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 replication is sustained in vivo

We hypothesized that the lack of robust and sustained replication of HIVJR-CSFΔvif following direct thymic infection could be due to limited CCR5 expression in the thymus, as <5% of thymocytes express CCR5 whereas 30–40% of thymocytes express CXCR4 [29]–[31]. We therefore introduced the deletion described above into the vif ORF of HIV-1LAI, a CXCR4-tropic virus (HIVLAIΔvif) and confirmed that the disruption of vif did not affect the ability of the virus to replicate in the absence of APOBEC3 (Figure S3). We tested our hypothesis by directly injecting HIVLAIΔvif into the thymus of four humanized mice. Viremia was present in 4/4 animals inoculated in this manner (Figure 6A). In contrast, when HIVLAIΔvif was directly injected into the spleen, liver, or lung of an additional 3 animals viral replication was absolutely restricted (Figure 6A). These results further demonstrate that Vif-independent HIV replication can be sustained following exposure into the thymus but is vigorously restricted in other tissues. Additionally, when HIVLAIΔvif was injected intravenously, sustained levels of viral replication were observed in the plasma of humanized mice; however this replication was lower relative to the parental virus (Figure 6B). Remarkably, unlike wild-type HIVLAI which rapidly depletes peripheral blood CD4+ T cells, infection with HIVLAIΔvif did not deplete CD4+ T cells in the periphery despite sustained viral replication (Figure 6C). Sequencing of viral RNA obtained from the plasma of HIVLAIΔvif infected mice showed significantly fewer G to A mutations compared to the same region of viral DNA isolated from PBMC, suggesting that the infection was likely being sustained in cells with lower APOBEC3 expression (Figure 6D).

Fig. 6. Sustained Vif-independent replication of CXCR4 tropic HIV-1.

(A) Plasma viral load was monitored in NSG-BLT humanized mice infected with 3.6×105 TCIU HIVLAIΔvif directly into the human thymic implant, spleen, liver, or lung. Direct injection of HIVLAIΔvif into the thymus resulted in plasma viremia in 4/4 infections. (B) Longitudinal analysis of plasma viral load in humanized mice infected intravenously with 3.6×105 TCIU of HIVLAIΔvif (n = 7) or 3–9×104 TCIU of wild-type HIVLAI (n = 6). Data represent mean +/− SEM. (C) Longitudinal analysis of the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood of humanized mice infected in panel B. (D) Comparison of the G to A mutation frequency in the viral RNA from the plasma and the viral DNA from peripheral blood cells from mice intravenously infected with HIVLAIΔvif. Data represent mean +/− SEM from 18 sequences, ** p = 0.0066. (E) Detection of HIV DNA (+) by nested PCR from the tissues of BLT humanized mice in panels A and B. Negative tissues (−) yielded no amplified viral DNA using two independent nested PCR primer sets targeting separate regions of the viral genome. Direct injection of HIVLAIΔvif into the liver, lung or spleen resulted in limited tissue distribution of viral DNA. (F) Comparison of the G to A mutation frequency in viral DNA from the thymus compared to viral DNA from other tissues of mice infected intrathymically (n = 4) and intravenously (n = 7) with HIVLAIΔvif. Data represent mean +/− SEM from 83 sequences. (G) G to A mutational profile of all viral DNA from mice infected with HIVLAIΔvif. Percentages indicate the proportion of G to A mutations occurring at GG (blue), GA (red), or GY (black) sites. Consistent with these results, HIVLAIΔvif DNA was abundant in the tissues of intrathymically or intravenously exposed mice while direct exposure into the spleen, liver, or lung resulted in viral DNA sparsely present in the organs (Figure 6E). Since this virus could not restore Vif expression, its viral DNA had G to A mutations; however, consistent with the low expression of A3G and A3F in the thymus (Figure 5A, 5B and S1), significantly fewer G to A mutations were present in viral DNA amplified from the thymus when compared to the same region of the viral DNA amplified from other organs (Figure 6F). Analysis of the mutational profile in the HIVLAIΔvif DNA from the mice showed that 86% of all the G to A mutations occurred at GG dinucleotide sites (Figure 6G). The presence of hypermutated provirus in several tissues suggests that the HIV was not able to develop resistance to APOBEC3 by second site mutations in the absence of vif, but was instead persisting in a pool of cells that permitted replication (Figure 7). Taken together, these results demonstrate that HIV can sustain replication independent of vif escaping APOBEC3 restriction in vivo.

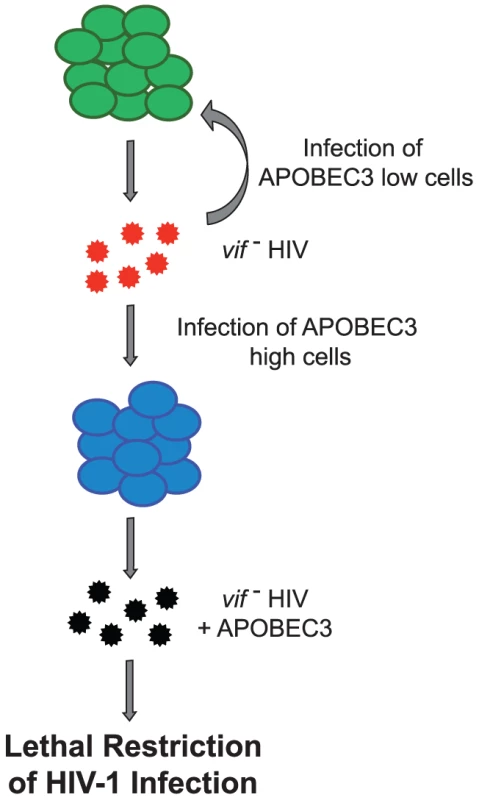

Fig. 7. Model depicting sustained in vivo replication of HIVLAIΔvif.

Ongoing viral replication persists in cells with low APOBEC3 (shown in green) with little to no APOBEC3 mutation but infection of cells expressing high APOBEC3 (shown in blue) leads to hypermutation of the viral genome, resulting in lethal restriction of HIV. Replication competent viruses are shown in red, defective virions are shown in black. Discussion

Our results demonstrate evidence of vif-independent replication of HIV in an in vivo setting. The observation that infection with CCR5 tropic HIV is rapidly extinguished in the absence of vif while CXCR4 tropic HIV lacking vif can sustain replication suggests that vif-independent HIV replication is occurring in a location with a paucity of cells expressing CCR5, such as the thymus where <5% of cells express CCR5 while a far greater number of cells (30–40%) express CXCR4 [29]–[31]. Consistent with this observation, direct injection of vif-deficient HIV into organs resulted in detectable viral replication only following thymic infection. Remarkably, reversion of the vif ORF with HIVJR-CSFvifFS occurred in 100% of thymic exposures while being absolutely restricted when injected into all other organs, highlighting the potent antiretroviral activity of APOBEC3. Interestingly, despite the strong selective pressure applied by APOBEC3, we did not observe any evidence of vif-defective HIV-1JR-CSF altering its coreceptor usage to take advantage of the lower A3G and A3F expression in the thymus. Coreceptor switching is a complicated process involving multiple mutations in envelope that occurs over a period of years in patients [32]. During their short lifespan, coreceptor switching is not common in humanized mice and has only been reported in a single mouse [33].

Our results demonstrate massive inactivation of CCR5-tropic HIV-1 when the protective effects of Vif are absent. These results are consistent with previously published work by Sato et. al. [34]. Under their experimental conditions, these investigators found that vif-defective CCR5-tropic HIV did not replicate at all in humanized mice. Replication of HIV-1 with a functional vif gave a different result. In this case, there was a low level of G to A mutation in both A3G and A3F contexts in viral DNA sequences [34]. Thus, these authors confirmed in the humanized mouse model the early observations of the occasional occurrence of hypermutation of HIV-1 isolated from patients [35]–[38].

Analysis of HIV DNA in aborted infections for G to A hypermutation, the hallmark of APOBEC3 restriction, demonstrated that when HIV DNA was present, there was an overwhelming prevalence of mutations at GG dinucleotide sites indicating that in the absence of vif A3G is the dominant HIV restricting factor in vivo [10]–[12]. This conclusion is further supported by two recent papers using stably expressed A3F or gene targeting to create null mutants to systematically disrupt the individual APOBEC3 proteins that have elegantly demonstrated that A3G is the APOBEC3 family member that induces the preponderance of GG to AG mutations in vif-deficient HIV DNA [15], [39]. One substantial benefit of A3G restriction is that the mutation of GG to AG can be highly effective in inactivating viral genes because of the conversion of tryptophan codons (TGG) to stop codons (TAG, TGA, or TAA).

The lower level of GA to AA mutations that we observed suggests a contributory role for A3F in the overall level of G to A mutations we observed. The impact of A3F remains unclear however since the specificity of A3G for the GG context is not absolute and some of the GA to AA mutations we observed may have been created by A3G. A role for A3F in HIV restriction has been questioned recently but this issue remains unresolved in vivo [39], [40]. Future experiments with humanized mice will address this question.

The results presented here demonstrate that in vivo HIV fails to develop second-site mutations to compensate for the absolute loss of vif to overcome A3G induced mutation, which is in contrast to observations made with in vitro systems with ectopically expressed A3G [41], [42]. This potent restriction of HIV in vivo is not observed by inactivation of other HIV-1 accessory genes [43], [44]. To survive in vivo in the absence of vif, HIV relies on target cells with reduced A3G expression in which it can replicate as shown by the lack of G to A hypermutation in the cell free virus despite the abundance of G to A mutations present in viral DNA in several tissues with high levels of A3G expression. Our analysis CD4+ cells identified thymocytes as a cell population that has reduced A3G expression. Previous analysis of A3G expression from whole tissues did not identify thymocytes as having reduced A3G; however these results are difficult to interpret because of the lower percentage of CD4+ cells in organs other than the thymus [45], [46]. Furthermore, the significance of A3G expression levels in the modulation of both wild-type and vif-deficient HIV replication has been previously demonstrated in Th1 and Th2 cells [47].

The implications of our findings might not be limited to HIV. Rather they might also extend to other viruses and retroelements that are restricted by APOBEC3 proteins [3], [4], [6]–[8], [48], as they may also persist as a result of reduced APOBEC3 expression that affords them the opportunity to replicate. The expansive restricting activity of the APOBEC3 family on endogenous and exogenous retroviruses serves to illustrate the broad therapeutic implications of our observations. This study also raises an important issue that must be addressed if the Vif-APOBEC3 axis is to be used to develop small molecular inhibitors of HIV replication: the well-documented ability of HIV to develop resistance to all current antiretroviral drugs. By incorporating point mutations in the relevant viral genes HIV can develop drug resistance [49]. Our observation of Vif-independent replication after direct injection into the thymus are consistent with previous work in humanized mice [50] and highlight the potential for HIV to escape the effect of a therapeutic Vif inhibitor [51]–[53]. The drug resistant virus would then be capable of systemic dissemination. However, as with other antiretrovirals, the use of combination therapy may prevent the emergence of such resistance. The thymus plays a critical role in HIV infection as it is actively involved in immune reconstitution following suppression of viremia with antiretroviral therapy. While this immune reconstitution occurs better in children than in adults, extensive thymic damage and incomplete virus suppression hinder this process [54]–[56].

Finally, it remains to be established if sublethal restriction by other innate immune defense proteins such as Tetherin, Trim-5-alpha, SamHD1, etc. could allow the replication of other pathogenic viruses [1]. Therefore, our discovery has long lasting implications that provide an alternative view of the dynamic interplay between endogenous immune restriction factors and the broad spectrum of pathogens they control.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted following NIH guidelines for housing and care of laboratory animals and in accordance with The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-Chapel Hill) in accordance with protocols approved by the institution's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. UNC-Chapel Hill protocol number 12-170.

Proviral constructs, virus stocks and cell lines

Experiments were performed using the CCR5-tropic primary isolate HIV-1JR-CSF (accession # M38429) or the CXCR4-tropic molecular clone HIV-1LAI (accession # K02013) [57], [58]. Mutations disrupting vif were made in regions that did not affect the overlapping 3′ terminus of pol or the splice acceptor site of vpr. A non-revertible 172 nucleotide deletion in the 5′ half of HIV-1JR-CSF vif (HIVJR-CSFΔvif) was constructed by deleting nucleotides 5138 to 5309 between the NdeI and NcoI sites. A second HIV-1JR-CSF with a potentially revertible vif (HIVJR-CSFvifFS) was constructed by inserting a single adenosine after nucleotide 86 in vif by site directed mutagenesis. A non-revertible 178 nucleotide deletion in the 5′ half of HIV-1LAIvif (HIVLAIΔvif) was constructed by deleting nucleotides 4708–4885 between the NdeI and PflMI sites [59]. All constructs were analyzed by direct DNA sequencing prior to virus production. Virus stocks were generated by transfecting proviral DNA into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and tissue culture infectious units (TCIU) were determined using TZM-bl cells essentially as we have previously reported [24], [27], [60]. TZM-bl Hela cells and human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured at 37°C, 10% CO2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 IU penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (Cellgro). CEM-SS cells were cultured at 37°C, 5%CO2 in RPMI 1640 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 IU penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Cellgro).

To generate a permissive cell line that can be infected with CCR5-tropic HIV, CEM-SS cells were transduced with the retroviral vector pBabe-CCR5 obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program [61], [62]. pBabe-CCR5 and the packaging vector pEQPAM were co-transfected into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The culture supernatants were collected after 48 hours and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. Twenty-four well plates were coated with 40 µg of Retronectin (Takara) and then washed with PBS+2% BSA and incubated twice with 0.5 mL of the vector supernatants for one hour each. CEM-SS cells (3×105) were then incubated in the vector coated wells overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. The following day, the vector supernatant (0.5 mL) was added to the cells overnight. Transduced cells were selected in complete RPMI containing 0.5 µg/ml puromycin. Fluorescence activated cell sorting was used to isolate the CD4HiCCR5Hi population with a BD FACSAria (Becton-Dickinson), collecting the top 25%.

Viral cultures

CEM-SS cells were used to propagate both wild-type and vif-deficient HIVLAI while CCR5 expressing CEM-SS cells were used for spreading infections with both wild-type and vif-deficient HIVJR-CSF. Cells (1×106) were infected with virus stocks normalized to p24Gag or tissue culture infectious units in complete RPMI containing 4 µg/ml polybrene at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 4 hours. The cells were washed extensively with PBS and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in complete RPMI. Cell cultures were passaged every three days and a sample of the culture supernatant was collected for quantification of viral capsid protein by p24Gag ELISA.

APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F determination in thymocytes and CD4+ cells

Human CD4+ cells from humanized mouse spleen, liver, or lung were isolated using magnetic bead sorting (Stem Cell Technologies). A3G and A3F mRNA expression in cells was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) essentially as previously described [46], [47]. Briefly, cellular RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's protocol including the optional treatment with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) during extraction. Total RNA (10 ng) was used as the template in a one-step RT-PCR reaction with the TaqMan RNA-to-Ct 1 step kit (Applied Biosystems). Primers for human A3G and A3F mRNA [47] and for human TATA Box binding protein mRNA (Applied Biosystems) were used for amplification and human A3G and A3F mRNA levels were normalized as previously described [46]. A3G protein determination was performed by disrupting cells in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH = 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaF, 25 mM benzamidine, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM Na3VO2, 3 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% IGEPAL-630). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000×g for 10 minutes and the supernatant fraction was prepared for SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and immunoblotted for human A3G (NIH AIDS reagent program #9968) [63] and human GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology #2118). Protein bands were quantitated by determining density using ImageJ software (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2009).

in vivo analysis of virus replication

Mice were maintained with the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill under specific-pathogen free conditions. Humanized mice (BLT and NSG-hu) were generated and analyzed for reconstitution with human hematopoietic cells including human T cells by flow cytometry essentially as previously described [20], [21], [24], [25], [27], [28]. Humanized mice were inoculated with 3×104 or 9×104 TCIU of wild-type HIV-1LAI, 9×104 TCIU of wild-type HIV-1JR-CSF, 3.6×105 TCIU of HIVJR-CSFΔvif or HIVLAIΔvif, or 9×104 or 3.6×105 HIVJR-CSFvifFS intravenously by tail vein injection or into specific organs as indicated in the text. HIV-1 infection of humanized mice was monitored in peripheral blood by viral load analysis as previously described [27].

Molecular analysis of HIV-1 infection

Tissues were harvested for evaluation of HIV-1 infection essentially as previously described [21]. Genomic DNA from mononuclear cells (5×105–5×106) from animal tissues was prepared using QIAamp DNA blood mini columns (Qiagen) according to the manufacture's protocol. Viral RNA was isolated from plasma using QIAamp viral RNA columns (Qiagen) according to the manufacture's protocol including an optional treatment with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) during extraction and cDNA was generated using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Viral DNA or cDNA was amplified by nested PCR using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche).

All PCR primers amplify both HIV-1JR-CSF and HIV-1LAI and were designed to anneal in regions with the fewest possible putative APOBEC3 deamination sites to avoid potential primer mismatch due to APOBEC3 induced mutagenesis. HIV regions amplified include a 1.5 kb region in pol (RT: HIV-1JR-CSF 2493–4023; HIV-1LAI 2063–3595), a 1.4 kb region including vif and vpr (vif: HIV-1JR-CSF 4941–6399; HIV-1LAI 4511–5969), and a 900 base region in the 3′ viral genome (nef: HIV-1JR-CSF 8722–9634; HIV-1LAI 8328–9211). Amplification of both RT and nef was used to assess APOBEC3 hypermutation while vif was amplified to asses APOBEC3 hypermutation and to confirm the integrity (or restoration) of the ORF. Primer sequences were as follows: RT outer forward primer, GCTCTATTAGATACAGGAGC; reverse primer, CCTAATGCATATTGTGAGTCTG; RT inner forward primer, GTAGGACCTACACCTGTCAAC; reverse primer, CCTGCAAAGCTAGGTGAATTGC. Vif outer forward primer, CAGGGACAACAGAGATCC; reverse primer, GTGGGTACACAGGCATGTGTGG; vif inner forward primer, CTTTGGAA AGGACCAGCAAAGC; reverse primer, GATGCACAAAATAGAGTGGTGG. Nef outer forward primer, GAATAGTGCTGTTAGCTTGC; reverse primer, CTCAAGGCAAGCTTTATTGAGG; nef inner forward primer, TAGAGCTATTCGCCACATACC; nef inner reverse, CTTTATTGAGGCTTAAGCAGTGG. Amplified viral DNA was sequenced and compared to the corresponding proviral DNA sequence used to generate the viruses using the Highlighter sequence visualization tool (www.hiv.lanl.gov).

Statistics

One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test (alpha level, 0.01), Paired two-tailed t tests, and Unpaired two-tailed t tests were all performed using Prism version 4 (Graph Pad, La Jolla, CA). All data were plotted as mean +/ − SEM.

Accession numbers

The GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore) accession numbers for HIV-1JR-CSF and HIV-1LAI are M38429 and K02013. The GenPept (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein) accession numbers for APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F are NP_068594 and Q8IUX4.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. DuggalNK, EmermanM (2012) Evolutionary conflicts between viruses and restriction factors shape immunity. Nature reviews Immunology 12 : 687–695.

2. HatziioannouT, BieniaszPD (2011) Antiretroviral Restriction Factors. Current opinion in virology 1 : 526–532.

3. EsnaultC, HeidmannO, DelebecqueF, DewannieuxM, RibetD, et al. (2005) APOBEC3G cytidine deaminase inhibits retrotransposition of endogenous retroviruses. Nature 433 : 430–433.

4. SasadaA, Takaori-KondoA, ShirakawaK, KobayashiM, AbuduA, et al. (2005) APOBEC3G targets human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. Retrovirology 2 : 32.

5. SheehyAM, GaddisNC, ChoiJD, MalimMH (2002) Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418 : 646–650.

6. TsugeM, NoguchiC, AkiyamaR, MatsushitaM, KunihiroK, et al. (2010) G to A hypermutation of TT virus. Virus research 149 : 211–216.

7. TurelliP, MangeatB, JostS, VianinS, TronoD (2004) Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by APOBEC3G. Science 303 : 1829.

8. VartanianJP, GuetardD, HenryM, Wain-HobsonS (2008) Evidence for editing of human papillomavirus DNA by APOBEC3 in benign and precancerous lesions. Science 320 : 230–233.

9. ZhengYH, IrwinD, KurosuT, TokunagaK, SataT, et al. (2004) Human APOBEC3F is another host factor that blocks human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol 78 : 6073–6076.

10. HarrisRS, BishopKN, SheehyAM, CraigHM, Petersen-MahrtSK, et al. (2003) DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113 : 803–809.

11. LiddamentMT, BrownWL, SchumacherAJ, HarrisRS (2004) APOBEC3F properties and hypermutation preferences indicate activity against HIV-1 in vivo. Curr Biol 14 : 1385–1391.

12. YuQ, KonigR, PillaiS, ChilesK, KearneyM, et al. (2004) Single-strand specificity of APOBEC3G accounts for minus-strand deamination of the HIV genome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11 : 435–442.

13. BishopKN, HolmesRK, SheehyAM, DavidsonNO, ChoSJ, et al. (2004) Cytidine deamination of retroviral DNA by diverse APOBEC proteins. Current biology 14 : 1392–1396.

14. LangloisMA, BealeRC, ConticelloSG, NeubergerMS (2005) Mutational comparison of the single-domained APOBEC3C and double-domained APOBEC3F/G anti-retroviral cytidine deaminases provides insight into their DNA target site specificities. Nucleic acids research 33 : 1913–1923.

15. RefslandEW, HultquistJF, HarrisRS (2012) Endogenous Origins of HIV-1 G-to-A Hypermutation and Restriction in the Nonpermissive T Cell Line CEM2n. PLoS pathogens 8: e1002800.

16. LecossierD, BouchonnetF, ClavelF, HanceAJ (2003) Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300 : 1112.

17. MangeatB, TurelliP, CaronG, FriedliM, PerrinL, et al. (2003) Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 424 : 99–103.

18. ZhangH, YangB, PomerantzRJ, ZhangC, ArunachalamSC, et al. (2003) The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature 424 : 94–98.

19. SadlerHA, StengleinMD, HarrisRS, ManskyLM (2010) APOBEC3G contributes to HIV-1 variation through sublethal mutagenesis. Journal of virology 84 : 7396–7404.

20. DashPK, GorantlaS, GendelmanHE, KnibbeJ, CasaleGP, et al. (2011) Loss of neuronal integrity during progressive HIV-1 infection of humanized mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31 : 3148–3157.

21. MelkusMW, EstesJD, Padgett-ThomasA, GatlinJ, DentonPW, et al. (2006) Humanized mice mount specific adaptive and innate immune responses to EBV and TSST-1. Nat Med 12 : 1316–1322.

22. DentonPW, GarciaJV (2011) Humanized mouse models of HIV infection. AIDS reviews 13 : 135–148.

23. ShultzLD, BrehmMA, Garcia-MartinezJV, GreinerDL (2012) Humanized mice for immune system investigation: progress, promise and challenges. Nature reviews Immunology 12 : 786–798.

24. DentonPW, EstesJD, SunZ, OthienoFA, WeiBL, et al. (2008) Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis prevents vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in humanized BLT mice. PLoS Med 5: e16.

25. DentonPW, KriskoJF, PowellDA, MathiasM, KwakYT, et al. (2010) Systemic administration of antiretrovirals prior to exposure prevents rectal and intravenous HIV-1 transmission in humanized BLT mice. PloS one 5: e8829.

26. DentonPW, OlesenR, ChoudharySK, ArchinNM, WahlA, et al. (2012) Generation of HIV latency in humanized BLT mice. Journal of virology 86 : 630–634.

27. DentonPW, OthienoF, Martinez-TorresF, ZouW, KriskoJF, et al. (2011) Topically Applied 1% Tenofovir in Humanized BLT Mice Using the CAPRISA 004 Experimental Design Demonstrates Partial Protection from Vaginal HIV Infection Validating the BLT Model for the Evaluation of New Microbicide Candidates. Journal of virology 85 : 7582–93.

28. SunZ, DentonPW, EstesJD, OthienoFA, WeiBL, et al. (2007) Intrarectal transmission, systemic infection, and CD4+ T cell depletion in humanized mice infected with HIV-1. J Exp Med 204 : 705–714.

29. BerkowitzRD, BeckermanKP, SchallTJ, McCuneJM (1998) CXCR4 and CCR5 expression delineates targets for HIV-1 disruption of T cell differentiation. Journal of immunology 161 : 3702–3710.

30. KitchenSG, ZackJA (1999) Distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in fetal lymphoid organs: implications for pathogenesis in utero. AIDS research and human retroviruses 15 : 143–148.

31. ZamarchiR, AllavenaP, BorsettiA, StievanoL, ToselloV, et al. (2002) Expression and functional activity of CXCR-4 and CCR-5 chemokine receptors in human thymocytes. Clinical and experimental immunology 127 : 321–330.

32. RegoesRR, BonhoefferS (2005) The HIV coreceptor switch: a population dynamical perspective. Trends in microbiology 13 : 269–277.

33. InceWL, ZhangL, JiangQ, ArrildtK, SuL, et al. (2010) Evolution of the HIV-1 env gene in the Rag2−/ − gammaC−/ − humanized mouse model. Journal of virology 84 : 2740–2752.

34. SatoK, IzumiT, MisawaN, KobayashiT, YamashitaY, et al. (2010) Remarkable lethal G-to-A mutations in vif-proficient HIV-1 provirus by individual APOBEC3 proteins in humanized mice. Journal of virology 84 : 9546–9556.

35. JaniniM, RogersM, BirxDR, McCutchanFE (2001) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA sequences genetically damaged by hypermutation are often abundant in patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells and may be generated during near-simultaneous infection and activation of CD4(+) T cells. J Virol 75 : 7973–7986.

36. KijakGH, JaniniLM, TovanabutraS, Sanders-BuellE, ArroyoMA, et al. (2008) Variable contexts and levels of hypermutation in HIV-1 proviral genomes recovered from primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology 376 : 101–111.

37. PaceC, KellerJ, NolanD, JamesI, GaudieriS, et al. (2006) Population level analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 hypermutation and its relationship with APOBEC3G and vif genetic variation. J Virol 80 : 9259–9269.

38. SimonV, ZennouV, MurrayD, HuangY, HoDD, et al. (2005) Natural variation in Vif: differential impact on APOBEC3G/3F and a potential role in HIV-1 diversification. PLoS Pathog 1: e6.

39. MiyagiE, BrownCR, OpiS, KhanM, Goila-GaurR, et al. (2010) Stably expressed APOBEC3F has negligible antiviral activity. Journal of virology 84 : 11067–11075.

40. MulderLC, OomsM, MajdakS, SmedresmanJ, LinscheidC, et al. (2010) Moderate influence of human APOBEC3F on HIV-1 replication in primary lymphocytes. Journal of virology 84 : 9613–9617.

41. HacheG, AbbinkTE, BerkhoutB, HarrisRS (2009) Optimal translation initiation enables Vif-deficient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to escape restriction by APOBEC3G. J Virol 83 : 5956–5960.

42. HacheG, ShindoK, AlbinJS, HarrisRS (2008) Evolution of HIV-1 isolates that use a novel Vif-independent mechanism to resist restriction by human APOBEC3G. Curr Biol 18 : 819–824.

43. SatoK, MisawaN, FukuharaM, IwamiS, AnDS, et al. (2012) Vpu augments the initial burst phase of HIV-1 propagation and downregulates BST2 and CD4 in humanized mice. Journal of virology 86 : 5000–5013.

44. ZouW, DentonPW, WatkinsRL, KriskoJF, NochiT, et al. (2012) Nef functions in BLT mice to enhance HIV-1 replication and deplete CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. Retrovirology 9 : 44.

45. KoningFA, NewmanEN, KimEY, KunstmanKJ, WolinskySM, et al. (2009) Defining APOBEC3 expression patterns in human tissues and hematopoietic cell subsets. J Virol 83 : 9474–9485.

46. RefslandEW, StengleinMD, ShindoK, AlbinJS, BrownWL, et al. (2010) Quantitative profiling of the full APOBEC3 mRNA repertoire in lymphocytes and tissues: implications for HIV-1 restriction. Nucleic acids research 38 : 4274–4284.

47. VetterML, JohnsonME, AntonsAK, UnutmazD, D'AquilaRT (2009) Differences in APOBEC3G expression in CD4+ T helper lymphocyte subtypes modulate HIV-1 infectivity. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000292.

48. RussellRA, WiegandHL, MooreMD, SchaferA, McClureMO, et al. (2005) Foamy virus Bet proteins function as novel inhibitors of the APOBEC3 family of innate antiretroviral defense factors. Journal of virology 79 : 8724–8731.

49. JohnsonVA, CalvezV, GunthardHF, ParedesR, PillayD, et al. (2011) 2011 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Topics in antiviral medicine 19 : 156–164.

50. AldrovandiGM, ZackJA (1996) Replication and pathogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 accessory gene mutants in SCID-hu mice. Journal of virology 70 : 1505–1511.

51. CenS, PengZG, LiXY, LiZR, MaJ, et al. (2010) Small molecular compounds inhibit HIV-1 replication through specifically stabilizing APOBEC3G. The Journal of biological chemistry 285 : 16546–16552.

52. NathansR, CaoH, SharovaN, AliA, SharkeyM, et al. (2008) Small-molecule inhibition of HIV-1 Vif. Nat Biotechnol 26 : 1187–1192.

53. ZuoT, LiuD, LvW, WangX, WangJ, et al. (2012) Small-Molecule Inhibition of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Replication by Targeting of the Interaction between Vif and ElonginC. Journal of virology 86 : 5497–507.

54. DouekDC, KoupRA, McFarlandRD, SullivanJL, LuzuriagaK (2000) Effect of HIV on thymic function before and after antiretroviral therapy in children. The Journal of infectious diseases 181 : 1479–1482.

55. DouekDC, McFarlandRD, KeiserPH, GageEA, MasseyJM, et al. (1998) Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature 396 : 690–695.

56. YeP, KirschnerDE, KourtisAP (2004) The thymus during HIV disease: role in pathogenesis and in immune recovery. Current HIV research 2 : 177–183.

57. KoyanagiY, MilesS, MitsuyasuRT, MerrillJE, VintersHV, et al. (1987) Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science 236 : 819–822.

58. PedenK, EmermanM, MontagnierL (1991) Changes in growth properties on passage in tissue culture of viruses derived from infectious molecular clones of HIV-1LAI, HIV-1MAL, and HIV-1ELI. Virology 185 : 661–672.

59. KarczewskiMK, StrebelK (1996) Cytoskeleton association and virion incorporation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein. Journal of virology 70 : 494–507.

60. WeiBL, DentonPW, O'NeillE, LuoT, FosterJL, et al. (2005) Inhibition of lysosome and proteasome function enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Journal of virology 79 : 5705–5712.

61. DengH, LiuR, EllmeierW, ChoeS, UnutmazD, et al. (1996) Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381 : 661–666.

62. MorgensternJP, LandH (1990) Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res 18 : 3587–3596.

63. StopakK, de NoronhaC, YonemotoW, GreeneWC (2003) HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol Cell 12 : 591–601.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 3- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Surviving the Heat of the Moment: A Fungal Pathogens Perspective

- Redefining the Immune System as a Social Interface for Cooperative Processes

- Post-Treatment HIV-1 Controllers with a Long-Term Virological Remission after the Interruption of Early Initiated Antiretroviral Therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study

- Rational Engineering of Recombinant Picornavirus Capsids to Produce Safe, Protective Vaccine Antigen

- Influenza Virus Aerosols in Human Exhaled Breath: Particle Size, Culturability, and Effect of Surgical Masks

- Glycomic Analysis of Human Respiratory Tract Tissues and Correlation with Influenza Virus Infection

- Evolution of Virulence in Emerging Epidemics

- Monomeric Nucleoprotein of Influenza A Virus

- The Enterovirus 71 A-particle Forms a Gateway to Allow Genome Release: A CryoEM Study of Picornavirus Uncoating

- HIV Restriction by APOBEC3 in Humanized Mice

- Transcriptional Responses of Praziquantel Exposure in Schistosomes Identifies a Functional Role for Calcium Signalling Pathway Member CamKII

- Genome-wide Determinants of Proviral Targeting, Clonal Abundance and Expression in Natural HTLV-1 Infection

- TIM-3 Does Not Act as a Receptor for Galectin-9

- Chronic Wasting Disease in Bank Voles: Characterisation of the Shortest Incubation Time Model for Prion Diseases

- Escapes Fumagillin Control in Honey Bees

- Generators of Phenotypic Diversity in the Evolution of Pathogenic Microorganisms

- Plasminogen Controls Inflammation and Pathogenesis of Influenza Virus Infections via Fibrinolysis

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Escapes Fumagillin Control in Honey Bees

- TIM-3 Does Not Act as a Receptor for Galectin-9

- HIV Restriction by APOBEC3 in Humanized Mice

- Influenza Virus Aerosols in Human Exhaled Breath: Particle Size, Culturability, and Effect of Surgical Masks

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání