-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaRhesus TRIM5α Disrupts the HIV-1 Capsid at the InterHexamer Interfaces

TRIM proteins play important roles in the innate immune defense against retroviral infection, including human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1). Rhesus macaque TRIM5α (TRIM5αrh) targets the HIV-1 capsid and blocks infection at an early post-entry stage, prior to reverse transcription. Studies have shown that binding of TRIM5α to the assembled capsid is essential for restriction and requires the coiled-coil and B30.2/SPRY domains, but the molecular mechanism of restriction is not fully understood. In this study, we investigated, by cryoEM combined with mutagenesis and chemical cross-linking, the direct interactions between HIV-1 capsid protein (CA) assemblies and purified TRIM5αrh containing coiled-coil and SPRY domains (CC-SPRYrh). Concentration-dependent binding of CC-SPRYrh to CA assemblies was observed, while under equivalent conditions the human protein did not bind. Importantly, CC-SPRYrh, but not its human counterpart, disrupted CA tubes in a non-random fashion, releasing fragments of protofilaments consisting of CA hexamers without dissociation into monomers. Furthermore, such structural destruction was prevented by inter-hexamer crosslinking using P207C/T216C mutant CA with disulfide bonds at the CTD-CTD trimer interface of capsid assemblies, but not by intra-hexamer crosslinking via A14C/E45C at the NTD-NTD interface. The same disruption effect by TRIM5αrh on the inter-hexamer interfaces also occurred with purified intact HIV-1 cores. These results provide insights concerning how TRIM5α disrupts the virion core and demonstrate that structural damage of the viral capsid by TRIM5α is likely one of the important components of the mechanism of TRIM5α-mediated HIV-1 restriction.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002009

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002009Summary

TRIM proteins play important roles in the innate immune defense against retroviral infection, including human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1). Rhesus macaque TRIM5α (TRIM5αrh) targets the HIV-1 capsid and blocks infection at an early post-entry stage, prior to reverse transcription. Studies have shown that binding of TRIM5α to the assembled capsid is essential for restriction and requires the coiled-coil and B30.2/SPRY domains, but the molecular mechanism of restriction is not fully understood. In this study, we investigated, by cryoEM combined with mutagenesis and chemical cross-linking, the direct interactions between HIV-1 capsid protein (CA) assemblies and purified TRIM5αrh containing coiled-coil and SPRY domains (CC-SPRYrh). Concentration-dependent binding of CC-SPRYrh to CA assemblies was observed, while under equivalent conditions the human protein did not bind. Importantly, CC-SPRYrh, but not its human counterpart, disrupted CA tubes in a non-random fashion, releasing fragments of protofilaments consisting of CA hexamers without dissociation into monomers. Furthermore, such structural destruction was prevented by inter-hexamer crosslinking using P207C/T216C mutant CA with disulfide bonds at the CTD-CTD trimer interface of capsid assemblies, but not by intra-hexamer crosslinking via A14C/E45C at the NTD-NTD interface. The same disruption effect by TRIM5αrh on the inter-hexamer interfaces also occurred with purified intact HIV-1 cores. These results provide insights concerning how TRIM5α disrupts the virion core and demonstrate that structural damage of the viral capsid by TRIM5α is likely one of the important components of the mechanism of TRIM5α-mediated HIV-1 restriction.

Introduction

TRIM5α is an important component of the innate immune defense against retroviral infection, including human immunodeficiency virus type -1 (HIV-1) [1], [2], and numerous studies suggest that TRIM5α interacts with assembled capsids and induces premature capsid disassembly (uncoating), before reverse transcription takes place [3]–[6]. TRIM5α is a 56 kD protein comprising a tripartite motif (TRIM; with RING, B-box 2, and coiled-coil (CC) domains) followed by a C-terminal B30.2/SPRY domain [7]–[9]. Each of these domains plays distinct roles in the antiviral function of TRIM5α. The B30.2/SPRY domain binds to the viral capsid and determines the specificity of restriction, with sequence variation within this domain greatly impacting binding specificity [6], [10]–[16]. For example, a single amino acid change in human TRIM5α (TRIM5αhu), R332P, renders the protein capable of binding the HIV-1 capsid, causing it to behave like rhesus TRIM5α (TRIM5αrh) with regard to HIV-1 restriction [11], [17]. The CC domain is necessary and sufficient for TRIM5α homo-dimerization, and this is important for capsid binding and restriction [12], [18]–[20]. In vitro, specific recognition and binding to a hexagonal CA lattice requires both the CC and SPRY domains [19]. The B-box 2 domain is thought to be involved in higher-order structure formation and self-association, and its presence in the protein enhances TRIM5α binding to the capsid, compared to the CC-SPRY domains alone [21], [22]. Several mutations in the B-box 2 domain abrogate HIV-1 restriction by TRIM5αrh [22]–[24]. The N-terminal RING domain is the least explored domain of TRIM5α. In general, RING domains are components of a particular class of E3 ubiquitin ligases that are involved in proteasome-mediated protein degradation (reviewed in [25]). TRIM5α exhibits E3 activity, but the role of the ubiquitin ligase activity in retrovirus restriction is unclear. Deletion of the N-terminal RING domain reduces, but does not abolish antiviral restriction [23], [26], and treatment of cells with proteasome inhibitors does not prevent restriction by TRIM5α [27]. However, proteasome activity is necessary for the TRIM5α-mediated block to reverse transcription [27], and engagement of restriction-sensitive virus cores results in proteasome-dependent degradation of TRIM5α [28]. Together, these data suggest that TRIM5α action in host restriction of retroviruses involves all of its domains.

The negative influence of TRIM5α on viral reverse transcription is well established [1], [3], [4], [6], [29], [30], however, the detailed mechanism of restriction has not been elucidated. TRIM5α binds to assembled complexes composed of the CA-NC region of Pr55gag, but does not significantly interact with monomeric or soluble CA protein [31]. Furthermore, mutations in CA that decrease capsid stability appear to reduce TRIM5α binding in target cells, as HIV-1 particles with unstable cores are less effective at saturating TRIM5α-mediated restriction [5]. Finally, recent studies using a recombinant TRIM5αrh chimera, containing the RING domain of TRIM21, demonstrated that the hybrid protein binds to CA-NC tubular assemblies and causes shortening of the tubes [32], [33], or self-assembles into higher-order structures, enhanced by binding to a preformed CA-NC hexagonal template [34].

Here, we employed cryoEM to investigate the direct interactions of tubular HIV-1 capsid assemblies and purified HIV-1 cores with the TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY protein and the structural consequences of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding. We demonstrate that TRIM5αrh binding disrupts the tubes and creates non-random fragments. Specific inter-hexamer interfaces are preferentially broken, resulting in strings of subunits that are held together by the CA-CTD dimer. We further demonstrate that disruption by TRIM5αrh of purified HIV-1 cores also occurred preferentially at the inter-hexamer interfaces. Our data suggest that TRIM5αrh-mediated HIV-1 restriction involves direct engagement of the viral capsid, and structural damage to the capsid is likely one of the key components in this event.

Results and Discussion

Expression, purification, and biophysical characterization of recombinant TRIM5α CC-SPRY

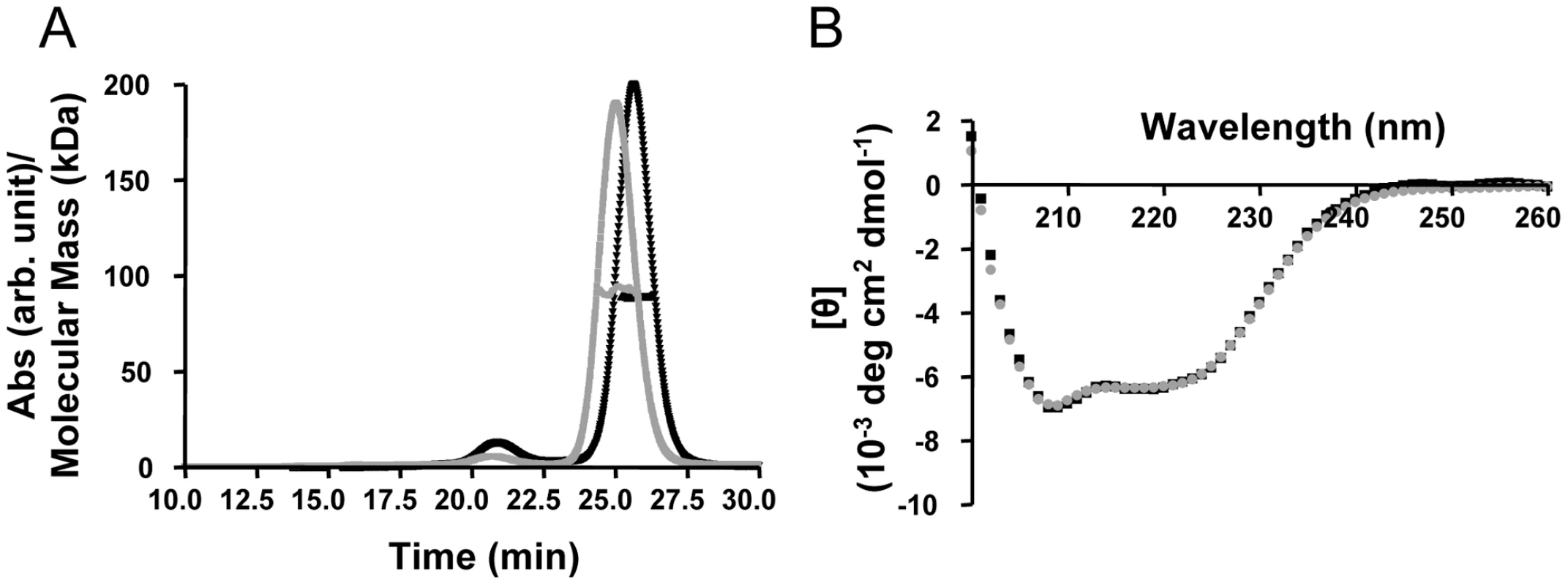

To investigate the direct interactions between TRIM5αrh and the HIV-1 capsid, we generated purified recombinant proteins. Full length, wild-type TRIM5αrh has been quite difficult to obtain in sufficient quantities for biophysical and structural studies [32], [35]. Therefore, we tested the expression and solubility of a number of different TRIM5αrh constructs, including one that comprises the CC-SPRY portion, by performing transient expression in SF9 insect cells. TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (residues 134–497) and TRIM5αhu CC-SPRY (residues of 132–493) exhibited sufficient protein levels and solubility and, therefore, were selected for production in SF21 insect cells, using recombinant baculoviruses. The quaternary state of the purified recombinant human and rhesus TRIM5α CC-SPRY proteins was assessed by size exclusion chromatography in conjunction with in-line multi-angle light scattering, confirming that these proteins were dimers. The observed molecular masses extracted from the light scattering analyses are 92 kDa and 89 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1A), compared to the theoretical values of 46.1 kDa and 45.6 kDa, respectively, based on amino acid sequences. Both proteins gave rise to almost identical CD spectra with a predominantly α-helical signature (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Biophysical characterization of recombinant TRIM5α CC-SPRY.

(A) Multi angle light scattering data. Elution profiles (A280 values) for rhesus monkey and human TRIM5α CC-SPRY proteins are shown in black and gray, respectively, and the calculated molecular masses obtained from the light scattering are shown with black and gray symbols across the peaks. (B) Superposition of the CD spectra of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (black) and TRIM5αhu CC-SPRY (gray). TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binds to HIV-1 CA and CA-NC tubular assemblies in a dose-dependent manner

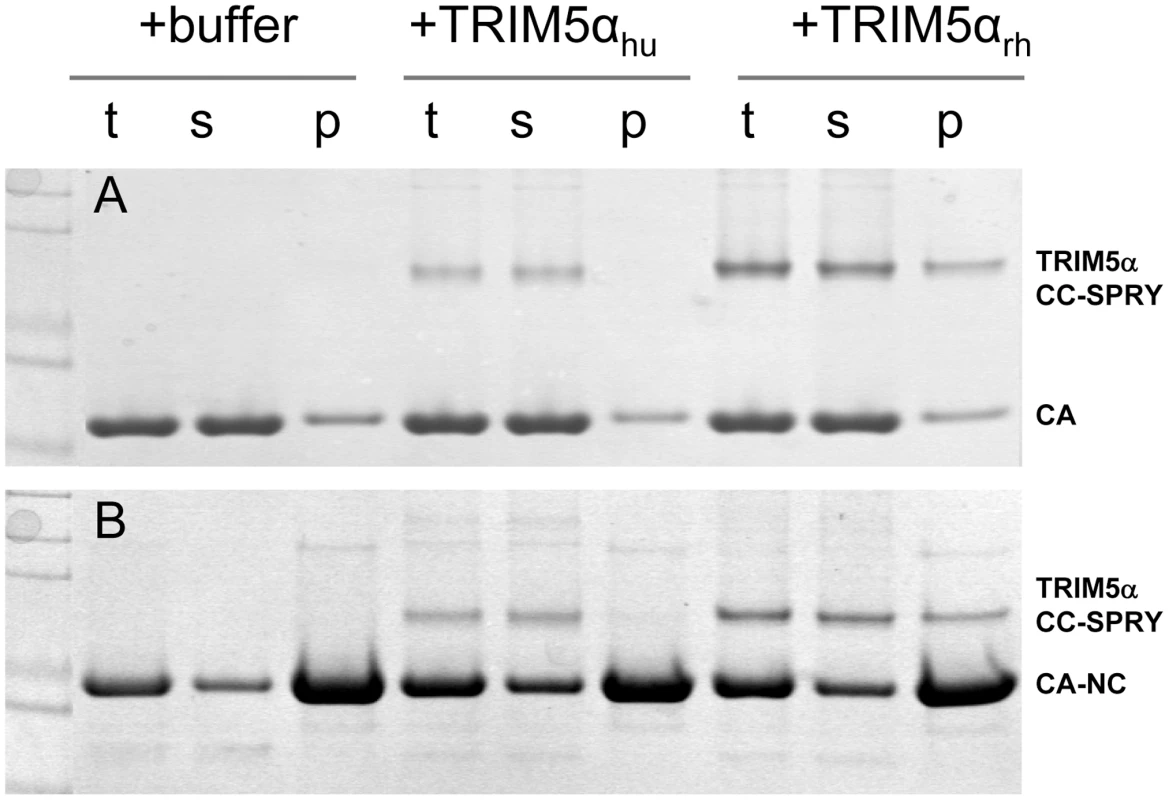

It is widely accepted that the restriction specificity of TRIM5α resides in its SPRY domain and that this domain interacts with retroviral capsids [1], [3], [11], [14], [15], [36]. However, only recently has direct binding been demonstrated for a TRIM5-21R fusion chimera with CA-NC assemblies [32], [34]. We used recombinant TRIM5α CC-SPRY proteins to examine direct binding to CA and CA-NC assemblies. Incubation of preassembled HIV-1 CA or CA-NC tubes with TRIM5αrh resulted in co-sedimentation of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY/CA or TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY/CA-NC complexes, respectively, in the pelleted fractions (Fig. 2, Fig. S1). More TRIM5αrh was observed bound to CA assemblies than to CA-NC assemblies (Figs. 2 & 3). In contrast, we observed negligible binding of TRIM5αhu CC-SPRY to HIV-1 CA or CA-NC complexes under the same assay conditions (Fig. 2). These data are consistent with previous results that demonstrated the inability of TRIM5αhu to bind and restrict HIV-1, but a capacity for the same protein to recognize N-tropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) capsid [3], [4], [12].

Fig. 2. Binding of TRIM5α CC-SPRY to pre-assembled wild-type CA and CA-NC tubes.

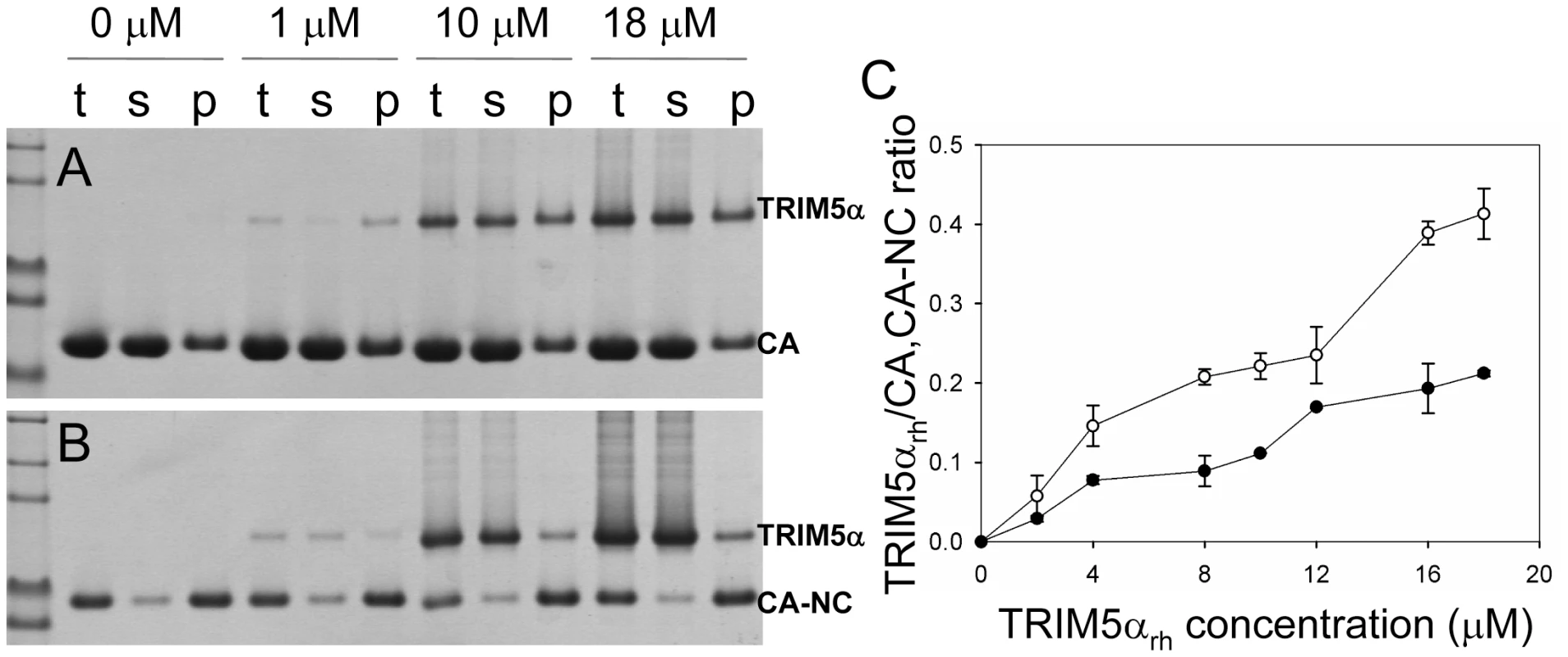

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of binding reactions using CA tubular assemblies (64 µM), incubated with either TRIM5αhu CC-SPRY (10 µM), TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (20 µM), or binding buffer. A control experiment under similar condition is shown in Fig. S1. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of binding reactions using CA-NC tubes (2 mg/ml), incubated with either TRIM5αhu CC-SPRY (10 µM), TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (20 µM) or binding buffer. Samples of the reaction mix before centrifugation (t), of supernatant (s), and of pellet (p) are shown. Fig. 3. Analysis of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding to the assembly of wild-type CA and CA-NC tubes.

(A&B) Increasing concentrations of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (0, 1, 10, 18 µM) were incubated with CA tubular assemblies (64 µM) (A) or with CA-NC tubular assembly mixture (10 µM) (B) and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE. Samples of the reaction mix before centrifugation (t), of supernatant (s), and of pellet (p) are shown. (C) TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY/CA (open circles) and TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY/CA-NC (closed circles) binding ratios at the indicated input concentrations of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY. Molar ratios of CA- or CA-NC-bound TRIM5α were determined by gel densitometry of proteins stained with Coomassie Blue in the appropriate lanes of the SDS-PAGE gels. Three independent experiments were carried out in duplicates. Mean values (± s.d.) are plotted. A more quantitative analysis of TRIM5αrh binding was carried out by measuring molar ratios of CA and CA-NC-bound TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY over a range of TRIM5αrh concentrations. Dose-dependent binding was observed for both CA and CA-NC assemblies (Fig. 3). Consistently, at all concentrations, TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY bound CA more efficiently than CA-NC. This could be due to differences in CA and CA-NC structures on the surfaces of the assemblies, or differences in the flexibility of these assemblies, as CA-NC tubes were assembled in the presence of oligonucleotide. The binding ratios were 0.41 for TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY/CA and 0.21 for TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY/CA-NC, respectively, for the highest concentration of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (18 µM). When a lower concentration of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (1 µM) was used for binding to the CA-NC tubular assemblies (10 µM), a molar ratio of 0.034 was obtained. This ratio is somewhat lower than the value reported by Langelier et al. for TRIM5-21R by immunoblotting [32]. The lower binding ratio for TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY is expected, since it lacks the self-associating B-box 2 domain, compared to the TRIM5-21R fusion protein. Furthermore, incubation with CC-SPRYrh did not alter the fraction of pelletable CA and CA-NC, even at the highest TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY concentrations (Figs. 2&3). These results are in accord with those reported for TRIM5-21R [32] and a binding study with CA-NC assemblies using TRIM5αrh-containing lysates [37]. Taken together, the data indicate that dimeric TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY directly interacts with tubular CA and CA-NC assemblies and that binding of TRIM5αrh does not dissociate these assemblies into soluble monomeric CA protein.

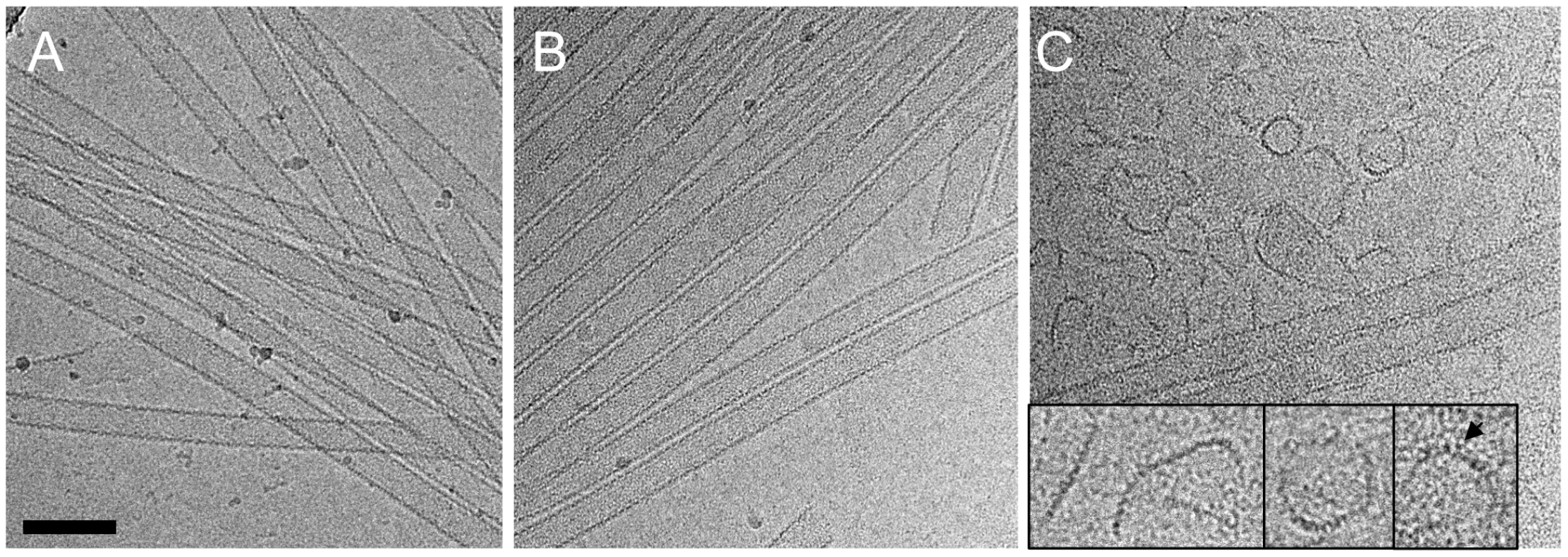

Binding of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY to tubular CA assemblies releases discrete, linear fragments

Although no dramatic effect of purified TRIM5αrh on uncoating has been observed in vitro using CA-NC assemblies [32], a substantial decrease in intact CA-NC tubes was noted when TRIM5αrh-containing cell lysates were mixed with CA-NC tubular assemblies [37]. To investigate this apparent dichotomy, we carried out cryoEM structural analyses of the samples that were used in the TRIM5α CC-SPRY/CA tubular assembly binding assays (Figs. 2A&3A). CryoEM micrographs showed well-ordered CA tubular structures after incubation with binding buffer only (Fig. 4A) or TRIM5αhu CC-SPRY (Fig. 4B), similar to our previously described assemblies [38]. In contrast, incubation of CA tubular assemblies with TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (18 µM) resulted in a massive structural break-down of the tubes (Fig. 4C), accompanied by the appearance of distinct fragments composed of strings of hexamers (Fig. 4C inset) [38]. The remaining tubes had generally lost the regularity of the hexagonal lattice. Some TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY densities apparently remained on several of the fragments (Fig. 4C inset). Gold-labeling of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY in complex with CA tubular assemblies confirmed that TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY bound to the CA assemblies (Fig. S2). These break-down fragments were primarily present in the pellet fraction after centrifugation (Fig. 3A), confirmed by cryoEM imaging of the pellet samples (Fig. S3), explaining why no effect on uncoating was detected in assays that measure soluble CA [32], [37]. These results suggest that the predominant effect of TRIM5αrh is the break down of HIV-1 capsids into fragments and not the dissociation into soluble monomers.

Fig. 4. CryoEM analysis of the TRIM5α CC-SPRY interaction with wild-type CA tubes.

(A–C) Low-dose projection images of CA assemblies (64 µM), incubated with binding buffer (A), human (B), or rhesus (C) TRIM5α CC-SPRY (18 µM). The displayed images are representative examples of four independent experiments. Inset, representative CA fragments, observed after TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding. Arrows indicate the TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY density on the CA fragments. Scale bars are 100 nm. We further examined the effect of CA mutations on TRIM5αrh disruption. Several CA mutants, including A92E, which was used in our previous structural study [38], and the E45A mutant, which produces hyperstable capsids, were analyzed. The effect of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding to A92E CA tubular assemblies was similar to that observed with wild-type CA (Fig. S4A&B). The CA tubular assemblies carrying the capsid-stabilizing E45A mutation [46] also experienced structural damage by TRIM5αrh, but to a lesser degree (Fig. S4C&D). This suggests that the overall stability of HIV-1 capsid assemblies may modulate or interfere with TRIM5αrh function, consistent with findings that hyperstable capsid core mutants effectively saturate TRIM5α-mediated restriction [5].

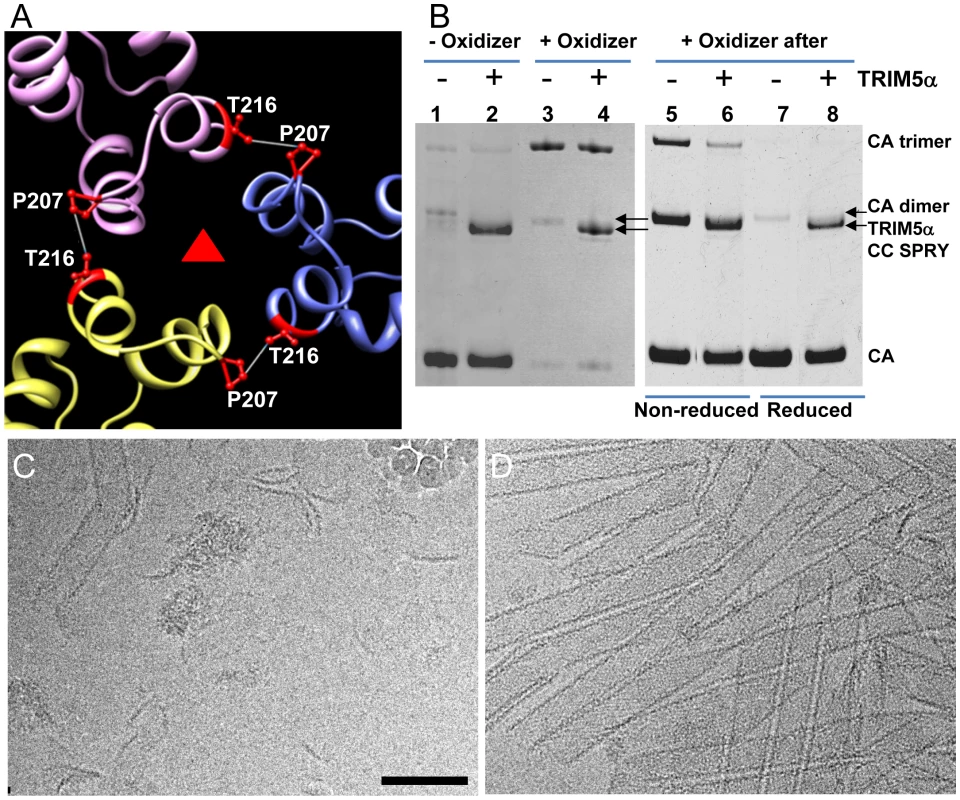

Cross-linking of the inter-hexamer CA interface prevents TRIM5αrh disruption

To determine which interface in the capsid lattice is disrupted by CC-SPRYrh, we tested the effect of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY on cross-linked CA tubular assemblies. In previous work, we showed that introduction of a pair of cysteines, P207C/T216C, at the pseudo three-fold inter-hexamer interface, efficiently cross-linked three neighboring CA molecules into trimers upon oxidation (Fig. 5A&B). The interactions at this interface are mediated by the CA-CTD, predominantly helices H10 and H11 [38]. Such cross-linked P207C/T216C CA tubular assemblies are expected to contain stronger hexamer-hexamer interactions, stabilizing the lattice. The P207C/T216C mutant assembles into tubular structures very similar to the wild-type CA (Fig. S5). Both oxidized and non-oxidized P207C/T216C CA tubular assemblies bound TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY, without any significant difference between them (Fig. 5B, lanes 1-4). However, cryoEM analysis revealed that TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY exerted very little structural damage onto the cross-linked tubes, whereas the non-oxidized tubular assemblies exhibited similar structural breakdown as seen for wild type CA tubes (Fig. 5C&D). These data suggest that TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY engages in inter-hexamer binding, most likely pulling apart the trimer interface, thereby disrupting the assembled tubes. We further tested this possibility by measuring the cross-linking efficiency of P207C/T216C CA assembly after TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY treatment. As can be seen from the results illustrated in Fig. 5B (lanes 5&6), the level of cross-linked trimers was significantly reduced after incubation with TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY. The percentage of the cross-linked CA trimer over total CA in the reduced sample is 3-fold less in the TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY treated sample, compared to untreated sample, confirming that the trimer interface between three neighboring hexamers is disrupted by TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY.

Fig. 5. Cross-linked CA assemblies resist structural damage by TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY.

(A) Amino acids at the pseudo three-fold axis in the molecular model of the tubular CA assemblies [38] were used to guide cysteine mutagenesis (P207C/T216C) for cross-linking of CA tubes. (B) Non-reducing SDS-PAGE analysis of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (18 µM) binding to cross-linked P207C/T216C CA tubes (left) and cross-linking of P207C/T216C CA tubes after TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY (18 µM) binding (right), visualized by Coomassie Blue staining. Pellets of non-reduced and reduced samples were analyzed in lanes 5&6 and 7&8, respectively. (C&D) CryoEM analysis of the structural effect of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding to P207C/T216C CA tubes without (C, corresponding sample in panel B, lane2) and with cross-linking (D, corresponding sample in panel B, lane4). Some ice particles inadvertently deposited on the EM grid during cryo-sample preparation are visible in panel C (upper right-hand region). The displayed images are representative examples of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 100 nm. An alternative scenario could involve binding of the TRIM5α CC-SPRY dimer within a CA hexamer, with TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY dimers pushing apart the hexamers. However, simple geometric considerations make this a very unlikely scenario if TRIM5αrh SPRY binds near the cyclophilin A binding loop in CA [39], since the distance between two sites (>110 Å) is too large for the TRIM5α CC-SPRY dimer protein to span. Nonetheless, we tested for this possibility using a A14C/E45C CA double cysteine mutant, which can cross-link CA within hexamers [40]. Following incubation with TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY, crosslinked A14C/E45C CA assemblies exhibited only a slight reduction in CA hexamers (Fig. S6, compare lanes 2 & 5), compared to the dramatic reduction of the trimer in the P207C/T216C CA assemblies (Fig. 5B, right panel). This small effect on the CA hexamer could be caused by minor perturbations at the intra-hexamer CA interfaces upon TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding. Small amounts of CA dimer (∼50kD, Fig. S6, lanes 1, 3, 5, 7&9) in the non-oxidized assemblies and dimer of hexamers (∼280kDa, Fig. S6, lanes 2&8) in the oxidized A14C/E45C CA assemblies were observed by SDS-PAGE, possibly due to the CA CTD dimer interaction. Interestingly, the amount of hexamer dimers was greatly diminished in the TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY treated sample (Fig. S6, lane 5 compared to lane 2&8). Again, these data further support that TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding perturbs the CA inter-hexamer interface.

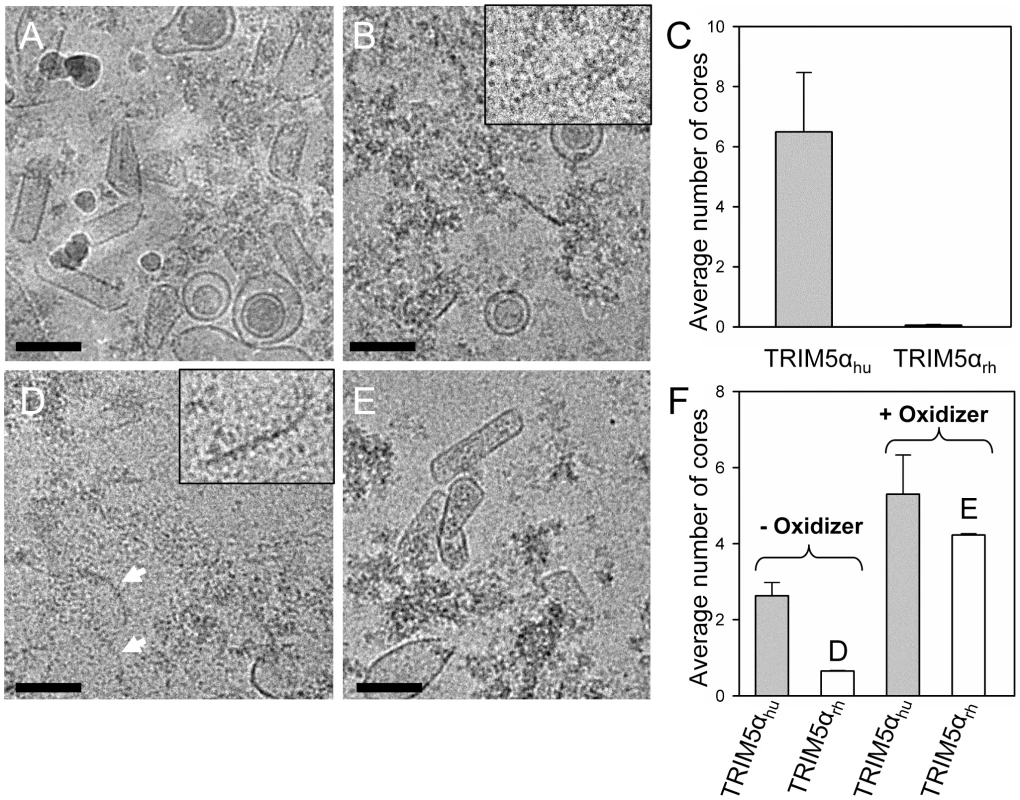

TRIM5αrh disrupts isolated HIV-1 cores similar to the in vitro capsid assemblies

To extend the above in vitro studies to biological HIV-1 capsids, we examined the effect of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY on isolated HIV-1 cores. For this purpose, we purified cores from the HIV-1 CA mutants A14C/E45C and P207C/T216C for two reasons; first, the mutant cores appeared to be more stable through the isolation procedure, and second, A14C/E45C and P207C/T216C cores bear the same cysteine mutations that we used for the in vitro analysis described in the previous section. A14C/E45C and P207C/T216C cores were isolated from virions in high yield (average of 44% of virion-associated CA, vs. ∼15% typically observed for wild type) by brief detergent treatment and sucrose gradient sedimentation. The CA protein in A14C/E45C cores was readily cross-linked into hexamers, as shown by non-reducing SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. S7). Despite the extensive CA hexameric crosslinking in A14C/E45C cores, incubation with TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY resulted in a dramatic loss of intact cores observed by cryoEM, compared to the samples treated with the same amount of human TRIM5α CC-SPRY (Fig. 6A-C). In contrast, no significant reduction in the number of P207C/T216C cross-linked cores was seen upon TRIM5αrh incubation (Fig. 6E and F, Fig. S7, +oxidizer samples). However, without ensuring effective cross-linking at the trimer interface (Fig. S7, -oxidizer), a four-fold decrease in the number of P207C/T216C cores was seen upon TRIM5αrh treatment, compared to incubation with TRIM5αhu (Fig. 6D and F, oxidizer samples). Although very few, a small number of P207C/T216C cores were observed in TRIM5αrh treated samples, presumably due to low levels of spontaneous crosslinking of isolated P207C/T216C cores at the trimer interface. Furthermore, similar protofilament fragments as seen for the in vitro assemblies were also observed after TRIM5αrh treatment of cores (Fig. 6D, arrows and inset). The above data demonstrate, for the first time, that TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY is capable of exerting direct structural damage on the isolated HIV-1 cores and TRIM5αrh binding preferentially disrupts the inter-hexamer interfaces in the HIV-1 capsid.

Fig. 6. Effects of TRIM5α CC-SPRYrh on isolated HIV-1 cores.

(A&B) Low-dose projection images of purified mutant A14C/E45C cores (11 µg/ml) incubated with human (A) or rhesus (B) TRIM5α CC-SPRY (18 µM). Scale bars, 100 nm. Inset, enlarged view of a core fragment in the TRIM5αrh-treated sample. (C) Quantification of the number of cores on the cryoEM grids. The mean values of the average number of cores per image from four independent experiments (80 cryoEM images) are shown, with the error bars representing one standard deviation. (D&E) Representative low-dose projection images of purified P207C/T216C cores, incubated with rhesus TRIM5α CC-SPRY (18 µM), without (D) and with (E) oxidation for cross-linking. Scale bars, 100 nm. Inset, enlarged view of a core fragment in the TRIM5αrh-treated sample. (F) Quantification of the number of cores on the cryoEM grids. Representative cryoEM images from samples that are shown on panels D and E, respectively. A model for TRIM5αrh action on HIV-1 capsid

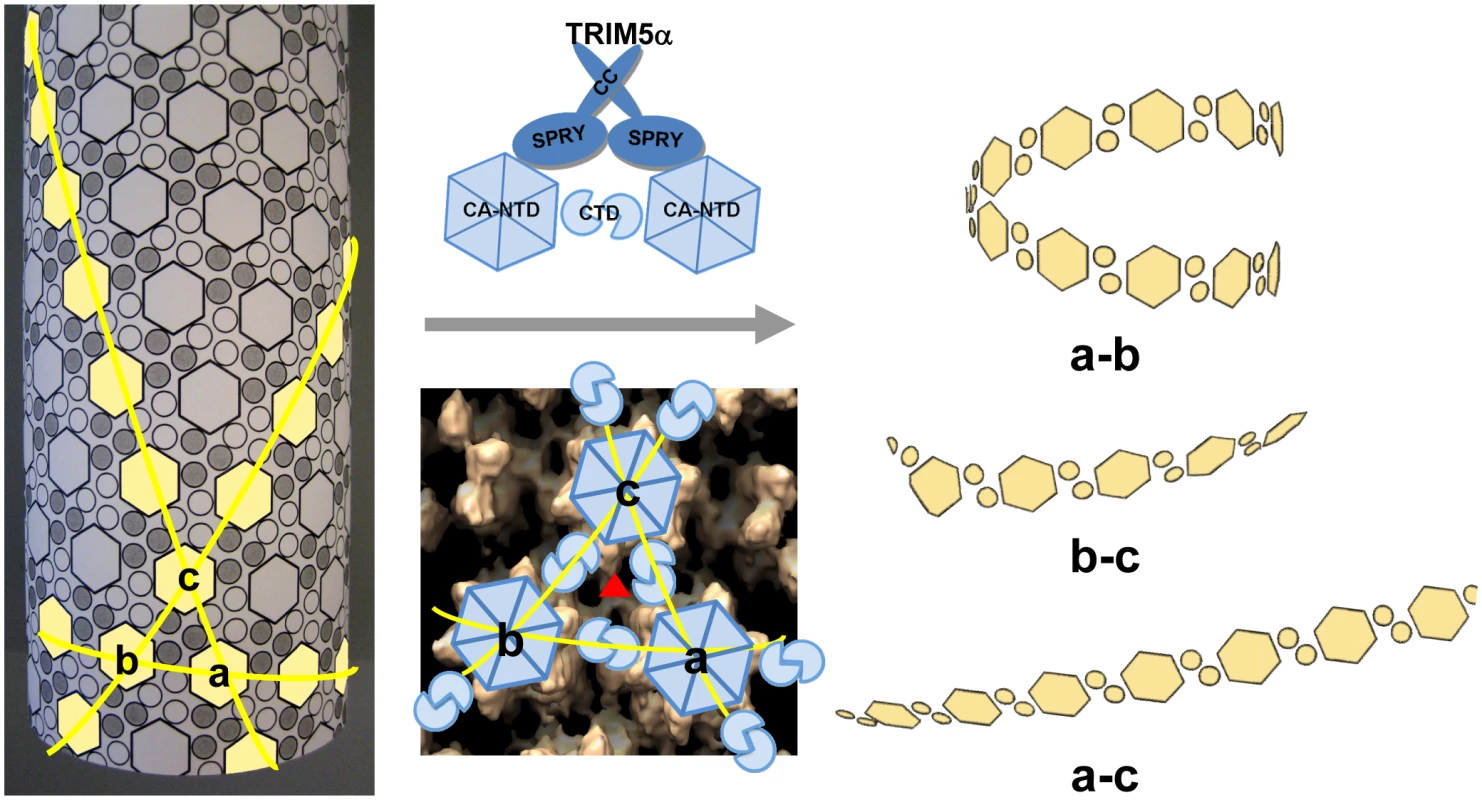

Examination of the fragments present in the cryoEM images revealed predominantly curved linear structures (Fig. 4C). These structures resemble fragments of protofilaments in CA helical assemblies. Our results are consistent with previous studies that TRIM5αrh binding to CA-NC assemblies did not increase soluble CA-NC monomers and dimers [32], [37], and further suggest that binding of TRIM5αrh disrupts the hexamer-hexamer interfaces, thereby releasing protofilaments along one of the three principal helical directions. A model based on the above findings is depicted schematically in Figure 7. CA assembles into helical tubes in vitro with a hexagonal surface unit formed by CA NTDs that is connected by CTD-CTD dimer and trimer interfaces on the inner surfaces of the three-dimensional tube or cone [38], [40], [41]. In these helical tubes, three slightly different inter-hexamer interactions were observed (see Fig. 3 in [38]). Binding of TRIM5αrh may disrupt these interactions differentially, weakening the CTD-CTD interfaces between hexamers. In turn, this causes release of CA protofilament fragments, such as those illustrated in Figure 7, and, indeed, similar types of fragments were observed in the cryoEM images (Fig. 4C). For TRIM5-21R interacting with CA-NC, shortening of tubes was observed in vitro, in addition to fragmentation [32]. Examples of this type of fragmentation of helical tubes have also been observed in other biological systems, including microtubules in vivo and in vitro [42], [43], actin filaments [44] and dynamin spirals and tubes [45]. Thus, the disassembly of the CA tubes into helical-type fragments is not unprecedented. Importantly, the use of two mutants, A14C/E45C and P207C/T216C, containing engineered disulfide bonds, allowed us to assign the site of TRIM5αrh action to the inter-hexamer interface (vs. the intra-hexamer interface), both, for in vitro assemblies and isolated HIV-1 cores, providing compelling evidence for specific structural disruption of the trimer interface of the HIV-1 capsid upon TRIM5α binding. In this manner, key insights into the mechanistic aspects of TRIM5αrh - capsid interaction were obtained.

Fig. 7. Model of TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY in HIV-1 CA restriction.

A schematic representation of the CA tubular assembly is shown at the left. CA NTD hexamers on the outside surface of the tube are depicted as hexagons, forming an extended hexagonal surface lattice that is connected by CA CTD dimers on the inner surface of the tube. Binding of TRIM5α CC-SPRY to assembled HIV-1 CA imposes stress on inter-hexamer interactions (middle panel, top) and weakens the CTD trimer interface (red triangle in middle panel, bottom), thereby causing damage to the lattice and releasing fragmented protofilaments. Based on our structural model for the CA tubular assemblies [38], three types of fragments containing linear arrays of CA hexameric units can be generated, depending on which of the three inter-hexamer interfaces are disrupted. For the short pitch helical arrays along the “a–b” direction, tightly curved or circular fragments are expected (top right), whereas significantly less curved fragments (bottom right) are expected for the longest pitch helical arrays along the “a–c” direction. Predicted fragments along the “b–c” direction should also be more linear than the tightly curved “a–b” direction fragments. Intermolecular cross-linking of the tubes strengthens the interfaces between the hexamers a, b and c, reducing TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY-mediated destructive effects. Retroviral uncoating is a poorly characterized process, generally defined as viral capsid disassembly following release of the viral core into the target cell. Studies using HIV-1 CA mutants indicate that the stability of the viral core is optimally balanced for efficient viral replication [46]. Therefore, a plausible mechanism for restriction by TRIM5α involves binding to the viral capsid, capsid destabilization, and perturbation of uncoating. Here, we show by cryoEM that TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding to CA assemblies causes massive destruction of assembled HIV-1 CA complexes. A similar effect was observed with purified HIV-1 cores. Intriguingly, this effect was seen with the TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY domain construct lacking the RING and B-box domains, albeit at high concentrations, even though TRIM5α protein devoid of RING and B-box domains was reported to lack restriction activity when expressed in cells [23], [24]. These seemingly inconsistent results could be due to several factors, including: (1) reduced binding to the viral capsid in the cell due to lack of self-association mediated by the B-box that can be overcome at high protein concentration in vitro; (2) improper intracellular localization of the deletion protein; or (3) altered association with host cell factors. We favor the first explanation, since the CC-CypA protein has been shown to restrict HIV-1 and FIV when expressed in target cells [47], and oligomerization of CypA appears sufficient to induce HIV-1 restriction [48]. Given the ability of the B-box domain to promote higher-order TRIM5α association [21], it seems plausible that this domain in intact TRIM5αrh may potentiate the effects observed here for TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY. Most importantly, while the CC-SPRY from rhesus TRIM5α was active on our in vitro assemblies and isolated cores, the corresponding human TRIM5α fragment was inactive. Thus, binding of the CC-SPRY domain to CA is essential for TRIM5α retroviral restriction and for structural disruption of the capsid. However, our current results do not exclude the possibility of additional structural consequences induced by higher-ordered oligomerization of TRIM5α on the viral capsid.

Although the molecular mechanism of TRIM5α restriction is not fully understood, current models hypothesize that after capsid release into the target cell, TRIM5α binds and triggers premature capsid disassembly. Our results suggest that direct binding of TRIM5α to the capsid is sufficient to inflict direct structural damage. Yet, cellular proteasome activity is clearly involved in the block to reverse transcription induced by TRIM5α[27]. Recruitment of proteasomes, most likely via the TRIM5α RING domain, may further disaggregate capsid fragments and also degrade TRIM5α [28], thereby mediating the irreversible block to infection. In contrast to TRIM5α-mediated restriction, Fv1 restriction of MLV does not result in inhibition of reverse transcription, yet both TRIM5α and Fv1 target the retroviral capsid. We speculate that the common feature in TRIM5α and Fv1 restriction is the structural damage to the capsid, with the major mechanistic difference involving recruitment of the proteasome in the case of TRIM5α-dependent restriction.

The findings presented here represent the first detailed structural analysis of TRIM5α disruption of the CA lattice to date. Additional structural studies of TRIM5α effects, especially with regard to the CTD-CTD interfaces in CA assemblies and HIV-1 cores, as well as the involvement of the RING and B-box domains, will further aid to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of TRIM5-mediated HIV-1 restriction and may offer insights into the HIV-1 virus-cellular interplay as well as lead to novel approaches in antiviral therapy.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

cDNAs encoding the coiled-coil and SPRY domains of human and rhesus TRIM5α (TRIM5α CC-SPRY; residues 132-493 and 134-497, respectively) were amplified and cloned into the pENT-TOPO vectors (Invitrogen), modified to encode a Strep-tag at the N-terminus and a His6-tag at the C-terminus of the proteins. The cDNAs encoding HIV-1 capsid (CA) and capsid - nucleocapsid (CA-NC) were amplified from pNL4-3 and cloned into the pET21 vector (Invitrogen). All clones were verified by sequencing of the entire coding region.

Baculoviruses expressing human and rhesus TRIM5α CC-SPRY were prepared using the Baculdirect C-term (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Proteins were expressed in SF21 insect cells by infecting cells with recombinant baculoviruses at a MOI of 2 for 40 h. Cells were lysed by sonication in a buffer containing 25 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% sodium azide. Soluble proteins were purified over a 5 mL Ni-NTA column followed by passage over a Hi-Load Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) in a buffer containing 25 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 0.02% sodium azide. The fraction containing TRIM5α CC-SPRY was further purified over a 5 mL Hi-Trap QP column (GE Healthcare) using a gradient of 0–1 M NaCl or a 5 mL StrepTrap-HP column (GE-Healthcare) using 2.5 mM desbiotin for elution. CA-NC proteins were expressed in E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3), cultured in Luria-Bertani medium, using 0.4 mM IPTG for induction and growth at 18°C for 23 h. The proteins were purified as described in Ganser et al [49]. Briefly, soluble proteins were precipitated with 40% (w/v) ammonium sulfate after DNA was removed by precipitation with polyethylenimine. The precipitates were dialyzed against a buffer containing 25 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 µM ZnSO4, 10 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% azide. Proteins were separated by column chromatography over a 5 mL Hi-Trap SP (GE Healthcare) with a 0–1 M NaCl gradient and Hi-Load Superdex75 26/60 columns, equilibrated with a buffer containing 25 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 µM ZnSO4, 10 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% azide. CA proteins were prepared as described in Byeon et al [38].

Isolation of HIV-1 core structures

HIV-1 cores were isolated from virions by a modification of the “spin-thru” method previously described [50]. HIV-1 viruses were derived from the R9 molecular clone [51] and mutants thereof. CA mutations were created by overlap PCR. SpeI-ApaI fragments were transferred into R9, and the transferred region was verified by PCR. HIV-1 viruses were produced by transient transfection of sixty dishes of 6×106 293T cells with 10 µg plasmid DNA (using 10 µg of HIV-1 construct R9, R9.Env-, or R9.A14C/E45C) using polyethylenimine (3.6 µg/ml, Polysciences) [52] in each 10 cm dish. Two days after transfection, virus-containing supernatants were collected and clarified by filtration (0.45 µm pore-size). Particles in clarified supernatants (600 ml) from 293T cells were pelleted through 3ml cushions of 20% sucrose (120,000 ×g, 2.5 h) in a Beckman SW32Ti rotor then gently suspended in a total of 1.2 ml STE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) for 2 h at 4°C. The concentrated virus suspension was subjected to equilibrium ultracentrifugation (120,000 × g, 16 h, 4°C, Beckman SW-32Ti rotor) through a layer of 1% Triton X-100 into a linear gradient of 30%–70% sucrose in STE buffer. Twelve 1-ml fractions were collected. CA concentrations were determined by p24 ELISA [53]. The peak p24 fractions near the bottom of the gradient were pooled and concentrated to ∼100 µl by diafiltration with an Ultracel-10K protein concentrator (Amicon). The sample was diluted with STE buffer and reconcentrated to reduce the final sucrose concentration in the sample to less than 0.5%. The concentrated samples of cores were then assayed for p24 by ELISA.

Multi-angle light scattering

Light-scattering data were obtained using an analytical Superdex200 column (1 cm ×30 cm, GE Healthcare) with in-line multi-angle light scattering (HELEOS, Wyatt Technology), variable wavelength UV (Agilent 1100 Series, Agilent Technology) and refractive index (Optilab rEX, Wyatt Technology.) detection. Approximately 100 µL of 2 mg/mL protein solutions were injected into the pre-equilibrated column using 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide at a flow-rate of 0.5 ml/minute for equilibration and elution. Molecular masses were determined from the scattering data using the ASTRA program (Wyatt Technology).

Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD spectra of TRIM5α CC-SPRY (5.4 µg/mL) were collected in a buffer containing 1 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 14 mM NaCl with a Jasco-810 CD spectrophotometer (Easton, MD). Data were collected with a scan rate of 1 nm/sec from 260 to 200 nm at a constant temperature of 12°C and averaged over 40 scans.

Binding assays

CA and CA-NC tubes were assembled containing 80 µM (2 mg/ml) CA, 1 M NaCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at 37°C for one hour or 300 µM CA-NC, 60 µM TG50 oligonucleotide in 250 µM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer at 4°C for 19 hr, respectively. For the TRIM5α CC-SPRY binding assays, the binding buffer, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 330 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 0.02% Azide, 5% Glycerol, is also the stock buffer for TRIM5α CC-SPRY proteins. Briefly, binding buffer containing different concentrations of TRIM5α CC-SPRY was added to preassembled CA and CA-NC tubes. CA concentration was slightly reduced to 64 µM in the binding assays. The CA-NC assemblies were diluted to final concentrations of 80 µM (comparable to the amount of total protein used with CA) or 10 µM (comparable to the number of tubes seen with CA) with assembly buffer prior to the binding assays. TRIM5αhuCC-SPRY or TRIM5αrhCC-SPRY aliquots from 4 mg/ml stock solutions were added to preassembled CA and CA-NC tubes. The reaction mixture was incubated on a rocking platform at room temperature for 1 hr with gentle mixing at 10 min intervals. At the end of incubation, 5 µl samples were withdrawn from the reaction mixtures and immediately used for cryoEM analysis. 6 µl samples from the same reaction mixtures were mixed with 4X LDS loading buffer (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 mM DTT for SDS-PAGE analysis (t). The remaining sample was pelleted at 20,000 g with an Eppendorf centrifuge 5417R for 15 min and supernatants (s) and pellets (p, resuspended in 1/3 of volume) were mixed with 4X LDS loading buffer for gel analysis. Total, supernatant, and pellet samples, without boiling, were loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. Each experiment was carried out at least three times.

Gold labeling of TRIM5α CC-SPRY

His-tagged TRIM5α proteins at the C-terminus, TRIM5αhuCC-SPRY and TRIM5αrhCC-SPRY, were labeled using 5 nm Ni-NTA-Nanogold gold beads from Nanoprobes (Yaphank, NY). For gold labeling, wild type CA protein was assembled into tubes using 80 µM (2 mg/ml) CA in the assembly buffer (1 M NaCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)) at 37°C for one hour. TRIM5αhuCC-SPRY or TRIM5αrhCC-SPRY (2 µl) was added to the assembly mix (20 µl) to a final concentration of 18 µM and incubated on a rocking platform at room temperature for 1 hr with gentle mixing at 10 min intervals. 2.7 µl of 5 nm Ni-NTA-Nanogold gold beads (stock concentration, 0.5 µM) in 100 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) was added to the assemblies and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 20 minutes. The mixture was then centrifuged at 3,000 g and the pellet was resuspended in assembly buffer. Samples were immediately applied to glow-discharged EM grids for negative staining with 1% uranyl acetate solution after resuspension. Images were acquired on an FEI Tecnai TF20 electron microscope at a nominal magnification of 50,000 and with underfocus values about 2 µm, using a Gatan ultrascan 4KX4K CCD camera (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, U.S.A.).

CA double-cysteine mutant cross-linking reactions

The cross-linking experiment was set up as previously described [54]. Briefly, 30 µl P207C/T216C or A14C/E45C CA were preassembled in the presence of 50 µM DTT under the conditions described above. The assembled material was then subjected to centrifugation at 20,000 g at room temperature in an Eppendorf centrifuge 5417R for 15 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in 30 µl assembling buffer and oxidized with 1 µl of 30x oxidizer mix (60 µM CuSO4, (Sigma) dissolved in water, and 267 µM 1,10-Phenanthroline (Sigma) dissolved in 100% ethanol in a 1∶1 ratio) for 5 seconds, immediately followed by quenching with 20 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma) and 3.7 mM Neocuproine (Sigma).

SDS-PAGE gel densitometry analysis

For the dose-dependent TRIM5αrh CC-SPRY binding assay, the SDS-PAGE gels were scanned (Epson 4990 scanner) and the integrated intensities of CA, CA-NC, and TRIM5αrh protein bands in pellet fractions were measured using Image J 1.40 g program (NIH). The molar ratios were calculated according to the formula (TRIM5αrh band intensity/TRIM5αrh molecular weight)/(CA band intensity/CA molecular weight).

Cryo-EM analysis

Aliquots from the binding assays (above) were subjected to cryoEM analysis. 2 µl were applied to the carbon side of a glow discharged perforated Quantifoil grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools, Jena, Germany), and 2.5 µl binding buffer was added to the back side of the grids. Grids were blotted and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a manual gravity plunger. Low dose (10∼15 e−/Å2) projection images were collected on an FEI Tecnai TF20 electron microscope at a nominal magnification of 50,000 and with underfocus values ranging from 1.0 to 2.5 µm, using a Gatan ultrascan 4KX4K CCD camera (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, U.S.A.).

Quantification of A14C/E45C and P207C/T216C cores in the presence of human and rhesus TRIM5α CC-SPRY

The effect of Rhesus TRIM5α CC-SPRY on HIV-1 cores was examined and quantified using cryoEM. 18 µM rhesus or human TRIM5α CC-SPRY proteins were added to a solution of isolated HIV-1 A14C/E45C or P207C/T216C cores (∼11 µg/ml). After one hour incubation at room temperature with gentle agitation, the samples were subjected to cryoEM analysis. For each sample, about 80 low dose projection images were collected at 19,000x magnification. Each field of view covers about 5 µm2. The image areas were chosen randomly, owing to the nature of cryoEM imaging. The number of cores in each sample was quantified using average number of cores per image frame. Mean values from four totally independent experiments are plotted in Fig. 6 with the standard deviation indicated.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. StremlauMOwensCMPerronMJKiesslingMAutissierP 2004 The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427 848 853

2. YapMWNisoleSLynchCStoyeJP 2004 Trim5alpha protein restricts both HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 10786 10791

3. StremlauMPerronMLeeMLiYSongB 2006 Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5alpha restriction factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 5514 5519

4. PerronMJStremlauMLeeMJavanbakhtHSongB 2007 The human TRIM5alpha restriction factor mediates accelerated uncoating of the N-tropic murine leukemia virus capsid. J Virol 81 2138 2148

5. ShiJAikenC 2006 Saturation of TRIM5 alpha-mediated restriction of HIV-1 infection depends on the stability of the incoming viral capsid. Virology 350 493 500

6. SebastianSLubanJ 2005 TRIM5alpha selectively binds a restriction-sensitive retroviral capsid. Retrovirology 2 40

7. ReymondAMeroniGFantozziAMerlaGCairoS 2001 The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J 20 2140 2151

8. NisoleSStoyeJPSaibA 2005 Trim family proteins: Retroviral restriction and antiviral defence. Nat Rev Microbiol 3 799 808

9. OzatoKShinDMChangTHMorseHC3rd 2008 TRIM family proteins and their emerging roles in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 8 849 860

10. StremlauMPerronMWelikalaSSodroskiJ 2005 Species-specific variation in the B30.2(SPRY) domain of TRIM5 alpha determines the potency of human immunodeficiency virus restriction. J Virol 79 3139 3145

11. YapMWNisoleSStoyeJP 2005 A single amino acid change in the SPRY domain of human Trim5 alpha leads to HIV-1 restriction. Curr Biol 15 73 78

12. Perez-CaballeroDHatziioannouTYangACowanSBieniaszPD 2005 Human tripartite motif 5 alpha domains responsible for retrovirus restriction activity and specificity. J Virol 79 8969 8978

13. SawyerSLWuLIEmermanMMalikHS 2005 Positive selection of primate TRIM5alpha identifies a critical species-specific retroviral restriction domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 2832 2837

14. OhkuraSYapMWSheldonTStoyeJP 2006 All three variable regions of the TRIM5alpha B30.2 domain can contribute to the specificity of retrovirus restriction. J Virol 80 8554 8565

15. SongBGoldBO'HuiginCJavanbakhtHLiX 2005 The B30.2(SPRY) domain of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5alpha exhibits lineage-specific length and sequence variation in primates. J Virol 79 6111 6121

16. JamesLCKeebleAHKhanZRhodesDATrowsdaleJ 2007 Structural basis for PRYSPRY-mediated tripartite motif (TRIM) protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 6200 6205

17. LiYLiXStremlauMLeeMSodroskiJ 2006 Removal of arginine 332 allows human TRIM5alpha to bind human immunodeficiency virus capsids and to restrict infection. J Virol 80 6738 6744

18. MischeCCJavanbakhtHSongBDiaz-GrifferoFStremlauM 2005 Retroviral restriction factor TRIM5alpha is a trimer. J Virol 79 14446 14450

19. JavanbakhtHYuanWYeungDFSongBDiaz-GrifferoF 2006 Characterization of TRIM5alpha trimerization and its contribution to human immunodeficiency virus capsid binding. Virology 353 234 246

20. MaillardPVEccoGOrtizMTronoD 2010 The specificity of TRIM5alpha-mediated restriction is influenced by its coiled-coil domain. J Virol 84 5790 801

21. LiXSodroskiJ 2008 The TRIM5alpha B-box 2 Domain Promotes Cooperative Binding to the Retroviral Capsid by Mediating Higher-order Self-association. J Virol 82 11495 502

22. Diaz-GrifferoFQinXRHayashiFKigawaTFinziA 2009 A B-Box 2 Surface Patch Important for TRIM5 alpha Self-Association, Capsid Binding Avidity, and Retrovirus Restriction. J Virol 83 10737 10751

23. JavanbakhtHDiaz-GrifferoFStremlauMSiZSodroskiJ 2005 The contribution of RING and B-box 2 domains to retroviral restriction mediated by monkey TRIM5alpha. J Biol Chem 280 26933 26940

24. Diaz-GrifferoFKarAPerronMXiangSHJavanbakhtH 2007 Modulation of retroviral restriction and proteasome inhibitor-resistant turnover by changes in the TRIM5alpha B-box 2 domain. J Virol 81 10362 10378

25. MeroniGDiez-RouxG 2005 TRIM/RBCC, a novel class of ‘single protein RING finger’ E3 ubiquitin ligases. Bioessays 27 1147 1157

26. Perez-CaballeroDHatziioannouTZhangFCowanSBieniaszPD 2005 Restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by TRIM-CypA occurs with rapid kinetics and independently of cytoplasmic bodies, ubiquitin, and proteasome activity. J Virol 79 15567 15572

27. WuXAndersonJLCampbellEMJosephAMHopeTJ 2006 Proteasome inhibitors uncouple rhesus TRIM5alpha restriction of HIV-1 reverse transcription and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 7465 7470

28. RoldCJAikenC 2008 Proteasomal degradation of TRIM5alpha during retrovirus restriction. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000074

29. BerthouxLSebastianSSayahDMLubanJ 2005 Disruption of human TRIM5alpha antiviral activity by nonhuman primate orthologues. J Virol 79 7883 7888

30. MunkCBrandtSMLuceroGLandauNR 2002 A dominant block to HIV-1 replication at reverse transcription in simian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 13843 13848

31. DoddingMPBockMYapMWStoyeJP 2005 Capsid processing requirements for abrogation of Fv1 and Ref1 restriction. J Virol 79 10571 10577

32. LangelierCRSandrinVEckertDMChristensenDEChandrasekaranV 2008 Biochemical characterization of a recombinant TRIM5alpha protein that restricts human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol 82 11682 11694

33. KarAKDiaz-GrifferoFLiYLiXSodroskiJ 2008 Biochemical and Biophysical Characterization of a Chimeric TRIM21-TRIM5alpha Protein. J Virol 82 11669 81

34. Ganser-PornillosBKChandrasekaranVPornillosOSodroskiJGSundquistWI 2011 Hexagonal assembly of a restricting TRIM5alpha protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.108 534 539

35. Diaz-GrifferoFLiXJavanbakhtHSongBWelikalaS 2006 Rapid turnover and polyubiquitylation of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5. Virology 349 300 315

36. LiXLiYStremlauMYuanWSongB 2006 Functional replacement of the RING, B-box 2, and coiled-coil domains of tripartite motif 5alpha (TRIM5alpha) by heterologous TRIM domains. J Virol 80 6198 6206

37. BlackLRAikenC 2010 TRIM5alpha disrupts the structure of assembled HIV-1 capsid complexes in vitro. J Virol 84 6564 6569

38. ByeonIJMengXJungJZhaoGYangR 2009 Structural convergence between Cryo-EM and NMR reveals intersubunit interactions critical for HIV-1 capsid function. Cell 139 780 790

39. OwensCMSongBPerronMJYangPCStremlauM 2004 Binding and susceptibility to postentry restriction factors in monkey cells are specified by distinct regions of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J Virol 78 5423 5437

40. PornillosOGanser-PornillosBKKellyBNHuaYWhitbyFG 2009 X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell 137 1282 1292

41. Ganser-PornillosBKChengAYeagerM 2007 Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell 131 70 79

42. DesaiAMitchisonTJ 1997 Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 13 83 117

43. NogalesEWangHW 2006 Structural intermediates in microtubule assembly and disassembly: how and why? Curr Opin Cell Biol 18 179 184

44. FujiwaraITakahashiSTadakumaHFunatsuTIshiwataS 2002 Microscopic analysis of polymerization dynamics with individual actin filaments. Nat Cell Biol 4 666 673

45. HinshawJESchmidSL 1995 Dynamin self-assembles into rings suggesting a mechanism for coated vesicle budding. Nature 374 190 192

46. ForsheyBMvon SchwedlerUSundquistWIAikenC 2002 Formation of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core of optimal stability is crucial for viral replication. J Virol 76 5667 5677

47. Diaz-GrifferoFKarALeeMStremlauMPoeschlaE 2007 Comparative requirements for the restriction of retrovirus infection by TRIM5alpha and TRIMCyp. Virology 369 400 410

48. YapMWMortuzaGBTaylorIAStoyeJP 2007 The design of artificial retroviral restriction factors. Virology 365 302 314

49. GanserBKLiSKlishkoVYFinchJTSundquistWI 1999 Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 283 80 83

50. AikenC 2009 Cell-free assays for HIV-1 uncoating. Methods Mol Biol 485 41 53

51. GallayPHopeTChinDTronoD 1997 HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells through the recognition of integrase by the importin/karyopherin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 9825 9830

52. DurocherYPerretSKamenA 2002 High-level and high-throughput recombinant protein production by transient transfection of suspension-growing human 293-EBNA1 cells. Nucleic Acids Res 30 E9

53. WehrlyKChesebroB 1997 p24 antigen capture assay for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus using readily available inexpensive reagents. Methods 12 288 293

54. PhillipsJMMurrayPSMurrayDVogtVM 2008 A molecular switch required for retrovirus assembly participates in the hexagonal immature lattice. EMBO J 27 1411 1420

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Spatial Distribution and Risk Factors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in ChinaČlánek HIV Integration Targeting: A Pathway Involving Transportin-3 and the Nuclear Pore Protein RanBP2Článek The Stealth Episome: Suppression of Gene Expression on the Excised Genomic Island PPHGI-1 from pv.Článek Sex and Death: The Effects of Innate Immune Factors on the Sexual Reproduction of Malaria ParasitesČlánek KIR Polymorphisms Modulate Peptide-Dependent Binding to an MHC Class I Ligand with a Bw6 MotifČlánek Viral EncephalomyelitisČlánek Longistatin, a Plasminogen Activator, Is Key to the Availability of Blood-Meals for Ixodid Ticks

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 3- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Strain-Encoded Relationship between PrP Replication, Stability and Processing in Neurons is Predictive of the Incubation Period of Disease

- Blood Meal-Derived Heme Decreases ROS Levels in the Midgut of and Allows Proliferation of Intestinal Microbiota

- Human Macrophage Responses to Clinical Isolates from the Complex Discriminate between Ancient and Modern Lineages

- Dendritic Cells and Hepatocytes Use Distinct Pathways to Process Protective Antigen from

- Spatial Distribution and Risk Factors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in China

- Rhesus TRIM5α Disrupts the HIV-1 Capsid at the InterHexamer Interfaces

- HIV Integration Targeting: A Pathway Involving Transportin-3 and the Nuclear Pore Protein RanBP2

- Antigenic Variation in Malaria Involves a Highly Structured Switching Pattern

- The Stealth Episome: Suppression of Gene Expression on the Excised Genomic Island PPHGI-1 from pv.

- Invasive Extravillous Trophoblasts Restrict Intracellular Growth and Spread of

- Novel Escape Mutants Suggest an Extensive TRIM5α Binding Site Spanning the Entire Outer Surface of the Murine Leukemia Virus Capsid Protein

- Global Functional Analyses of Cellular Responses to Pore-Forming Toxins

- Sex and Death: The Effects of Innate Immune Factors on the Sexual Reproduction of Malaria Parasites

- Lung Adenocarcinoma Originates from Retrovirus Infection of Proliferating Type 2 Pneumocytes during Pulmonary Post-Natal Development or Tissue Repair

- Botulinum Neurotoxin D Uses Synaptic Vesicle Protein SV2 and Gangliosides as Receptors

- The Moving Junction Protein RON8 Facilitates Firm Attachment and Host Cell Invasion in

- KIR Polymorphisms Modulate Peptide-Dependent Binding to an MHC Class I Ligand with a Bw6 Motif

- The Coxsackievirus B 3C Protease Cleaves MAVS and TRIF to Attenuate Host Type I Interferon and Apoptotic Signaling

- Dissection of the Influenza A Virus Endocytic Routes Reveals Macropinocytosis as an Alternative Entry Pathway

- Viral Encephalomyelitis

- Sheep and Goat BSE Propagate More Efficiently than Cattle BSE in Human PrP Transgenic Mice

- Longistatin, a Plasminogen Activator, Is Key to the Availability of Blood-Meals for Ixodid Ticks

- Metabolite Cross-Feeding Enhances Virulence in a Model Polymicrobial Infection

- A Toxin that Hijacks the Host Ubiquitin Proteolytic System

- Dynamic Imaging of the Effector Immune Response to Infection

- The Lectin Receptor Kinase LecRK-I.9 Is a Novel Resistance Component and a Potential Host Target for a RXLR Effector

- Host Iron Withholding Demands Siderophore Utilization for to Survive Macrophage Killing

- The Danger Signal S100B Integrates Pathogen– and Danger–Sensing Pathways to Restrain Inflammation

- The RNome and Its Commitment to Virulence

- A Novel Nuclear Factor TgNF3 Is a Dynamic Chromatin-Associated Component, Modulator of Nucleolar Architecture and Parasite Virulence

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Toxin that Hijacks the Host Ubiquitin Proteolytic System

- Invasive Extravillous Trophoblasts Restrict Intracellular Growth and Spread of

- Blood Meal-Derived Heme Decreases ROS Levels in the Midgut of and Allows Proliferation of Intestinal Microbiota

- Metabolite Cross-Feeding Enhances Virulence in a Model Polymicrobial Infection

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání