-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaClonal Evolutionary Analysis during HER2 Blockade in HER2-Positive Inflammatory Breast Cancer: A Phase II Open-Label Clinical Trial of Afatinib +/- Vinorelbine

In a phase 2 clinical trial in which patients received afatinib, plus vinorelbine on disease progression, Charles Swanton and colleagues study the mutational events in HER2-positive inflammatory breast cancers alongside early-stage clinical outcomes.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 13(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002136

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002136Summary

In a phase 2 clinical trial in which patients received afatinib, plus vinorelbine on disease progression, Charles Swanton and colleagues study the mutational events in HER2-positive inflammatory breast cancers alongside early-stage clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare, aggressive form of breast cancer that accounts for around 1%–6% of breast cancers [1–4]. IBC tends to affect younger women and has a high risk of local and distant metastasis. Prognosis is poor, with median survival estimated at 2.9 y in IBC patients versus 6.4 y in those with non-inflammatory, locally advanced breast cancer [3,5]. Current management of IBC involves a combination of anthracycline and taxane-based chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting, followed by surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, or radiotherapy [6].

IBC is thought to be a biologically distinct form of breast cancer, commonly lacking oestrogen (ER) and progesterone (PgR) receptor expression [7]. A greater frequency of HER2 and EGFR overexpression among IBC cases has been reported, occurring in 50% and 30% of patients, respectively [8]. Genomic profiling techniques have led to the identification of genes that are potentially involved in disease development [9–11]; however, HER2-positive IBC has not been characterised through deep exome sequencing.

EGFR and HER2 have been shown to be involved in tumour growth and metastasis of IBC, and as such represent therapeutic targets [12]. Afatinib is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that irreversibly and selectively blocks signalling from ErbB family members. Clinically, afatinib showed activity in phase II trials with HER2-positive breast cancer patients [13,14]. Most recently, in the phase III LUX-Breast 1 trial, afatinib combined with vinorelbine demonstrated similar progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response (OR) rates to trastuzumab plus vinorelbine in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer after failure on trastuzumab, but the afatinib-containing regimen was associated with shorter overall survival (OS) and was less tolerable [15].

We performed an open-label, single-arm phase II clinical trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of afatinib alone and in combination with vinorelbine following disease progression in patients with HER2-positive IBC. Recruitment to this trial was terminated early following the results of the LUX-Breast 1 trial. We carried out prospectively planned whole-exome sequencing of tumour biopsies at baseline and after progression on afatinib monotherapy to explore two questions: (1) what is the mutational landscape of HER2-positive IBC, and is it distinct from HER2-positive non-IBC; and (2) how does exposure to HER2 inhibition affect the evolution of IBC?

Methods

Study Design

This was an open-label, phase II, multicentre trial of afatinib for the treatment of HER2-positive IBC (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01325428, S1 and S2 Texts). Patients were treated with afatinib monotherapy until disease progression (Part A), and then afatinib and vinorelbine until disease progression (Part B).

PFS was assessed separately for Part A and Part B, and over the whole study. OS was only assessed over the whole study period. The primary endpoint was clinical benefit (defined as stable disease [SD] for ≥6 mo, partial response [PR], or complete response [CR]). Secondary endpoints were objective response (OR) and duration of OR and PFS; other endpoints included OS and safety.

Following the results of the LUX-Breast 1 trial, Part B was stopped and recruitment to the whole trial was stopped thereafter. Patients in Part A were informed that they would no longer be able to receive afatinib plus vinorelbine upon progression, and had to agree with the investigator regarding continuation of afatinib monotherapy. Patients in Part B who were deriving benefit from treatment could continue afatinib plus vinorelbine.

PR was considered to be confirmed if the criteria were met at least 4 wk later. SD had to be observed at least 42 days after first study drug administration in the respective part of the study to be considered for best overall response regardless of confirmation, and had to last for more than 182 d to qualify for clinical benefit.

The study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guideline and approved by the local ethics committees (S1 Appendix). All patients provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Patients

Female patients aged ≥18 y with investigator-confirmed IBC characterized by diffuse erythema and oedema (peau d’orange) with locally advanced or metastatic disease and histologically confirmed HER2-positive disease (i.e. immunohistochemistry [IHC] 3+ or IHC 2+ with FISH/SISH positivity) were eligible for the study (S1 Table). Patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status of 0–2 and life expectancy of ≥6 mo. Other exclusion criteria for the trial included: radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, trastuzumab, or surgery (other than biopsy) within 2 wk prior to the first dose of afatinib in Part A, known pre-existing interstitial lung disease, active brain metastases, significant chronic or recent acute gastrointestinal disorders with diarrhoea as a major symptom, any other current malignancy or malignancy diagnosed or relapsed within the past 5 y (other than non-melanomatous skin cancer and in situ cervical cancer), inadequate bone marrow, and renal and liver functions.

Treatments

In both parts of the study, patients received a single oral dose of afatinib 40 mg once daily until disease progression. The first dose was administered at the trial site, and subsequent doses were taken at home. Afatinib dose reductions were required for any drug-related grade ≥3 adverse events (AEs) and selected grade 2 AEs. The afatinib dose was reduced in 10 mg decrements to a minimum of 20 mg; all dose reductions were permanent. In Part B, patients received previously tolerated afatinib doses and additionally received short infusion (approximately 10 min) intravenous vinorelbine at a weekly dose of 25 mg/m2 in a 4-weekly course until disease progression. Vinorelbine treatment was administered at the trial site under the supervision of the investigator; treatment was withheld if platelet count was <100,000 cells/mm3 or absolute neutrophil count was <1,500 cells/mm3.

Assessments

Tumour assessments were performed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at screening and every 8 wk after the first dose of afatinib. Investigators evaluated response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. AEs were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

Tumour biopsies were obtained before afatinib treatment and on disease progression in Part A, snap frozen, and optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT)-embedded. Venous blood samples were obtained and genomic DNA was extracted. Whole-exome sequencing was performed on pre-treatment tumour biopsies, matched germline genomic DNA and post-treatment tumour biopsies according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon 50Mb Kit). Tumour and germline DNA were sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 to an average depth of 396x and 157x, respectively (S2 Table).

Mutation Calling and Genomic Analysis

Raw sequencing data were aligned to human genome sequence version hg19 using bwa (v0.5.9) [16], duplicates marked using Picard (v1.54), and indel realignment performed with GATK IndelRealigner (v1.0.6076) [17]. Somatic single nucleotide variant (SNV) calling was performed using VarScan2 (v2.3.7) [18], MuTect (v1.1.7) [19], Virmid (v1.1.0) [20], and Strelka (v1.0.14) [21]. SNVs called by ≥2 tools were further filtered for variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥5%. Small indels were identified using Pindel (v0.2.5a7) [22] and VarScan2 (v2.3.7). Indels called by both tools were further filtered for VAF ≥5%. Mutations in genes of interest were visualized with Oncoprints [23].

Tumour copy number aberrations, ploidy, and purity were determined using ASCAT 2 [24], which allows for exome sequencing data as input (available at https://github.com/Crick-CancerGenomics/ascat) (S3 Table). Some samples were excluded from copy number analysis due to low tumour content. Segmented copy number data were divided by sample mean ploidy and log2 transformed for GISTIC2.0 analysis [25]. Copy number segments were defined relative to ploidy as previously described [26]: amplification, gain, and loss were defined as log2(4/2), log2(2.5/2), and log2(1.5/2), respectively.

Genome-doubling status was determined as previously described [27]. Briefly, each sample, s, was represented as an aberration profile of major and minor allele copy numbers at chromosome arm resolution. The total number of aberrations (relative to diploid), Ns, and the probabilities of loss/gain for each allele at each chromosome arm, Ps, was calculated. Ten thousand simulations were run for each sample s, where Ns sequential aberrations, based on Ps, were applied to a diploid profile. A p-value for genome doubling was obtained by counting the percentage of simulations in which the proportion of chromosome arms with a major allele copy number ≥2 was higher than that observed in the sample.

The weighted Genomic Instability Index (wGII) was used to assess chromosomal instability [28]. Briefly, the percentage aberrant regions for each autosome was calculated separately and mean percentage aberration then calculated across all 22 chromosomes to account for variation in chromosome size, so that large chromosomes do not have a greater effect on the GII score than small chromosomes.

Mutational signatures were determined using the R package deconstructSigs [29]. Using this tool, the fraction of mutations in each of the 96 trinucleotide contexts was calculated, and the weighted combination of published signatures from [30] identified to most closely reconstruct the mutational profile of the sample.

The mutation copy number and cancer cell fraction of each mutation were calculated by integrating ASCAT-derived integer copy number and tumour purity estimates with the variant frequency as described in [31]. This was used as input for PyClone [32], which uses a hierarchical Bayesian Dirichlet process in order to infer clonal population structure. A modified version of PyClone was used as described in [33]; clusters with 3 or fewer SNVs were excluded.

HLA typing was performed with OptiType [34]. Nonsynonymous mutations were extracted from each tumour sample and translated into mutant peptide 9–11mers long [33]. Using the patient-specific HLA type, we used NetMHC (v2.8) [35] to predict the binding strength of each mutant and wildtype peptide to the respective MHC class I molecules. Somatic mutations that gave rise to peptides with a binding affinity of ≤500 nM were considered to be putatively neoantigenic.

TCGA Data

The comparison to the HER2-positive non-IBC cohort is based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov/ [36]. Tumour samples were filtered for positive HER2 IHC status (n = 131, S4 Table). For the matched cohort, a subset was selected by matching cases based on age (±10 years), ER, and PgR status; this allowed only for a one-to-one matching due to the limited number of TCGA cases available.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of efficacy and safety in this trial were descriptive and exploratory. A sample size of 40 patients was selected for this study; assuming an underlying clinical benefit rate of 50%, 40 patients would provide more than a 90% probability of observing a clinical benefit rate of at least 40%. Analyses of clinical benefit rate (CBR) and OR rate were planned for the following subgroups: hormone receptor (ER and PgR), EGFR status, new brain metastases, patients presenting with target lesions only versus those with non-target lesions only versus those with both, and prior trastuzumab therapy. Exploratory analyses using genomic data were planned to search for predictive markers of response and resistance to afatinib.

MutSigCV (v1.3) [37] and GISTIC2.0 [25] were used to determine mutational significance of somatic SNVs and somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs). Multiple-testing corrections in these tests were carried out using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate method. Mann-Whitney and Fisher’s exact test were used for comparison between two groups. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to test for significance.

Results

Patients

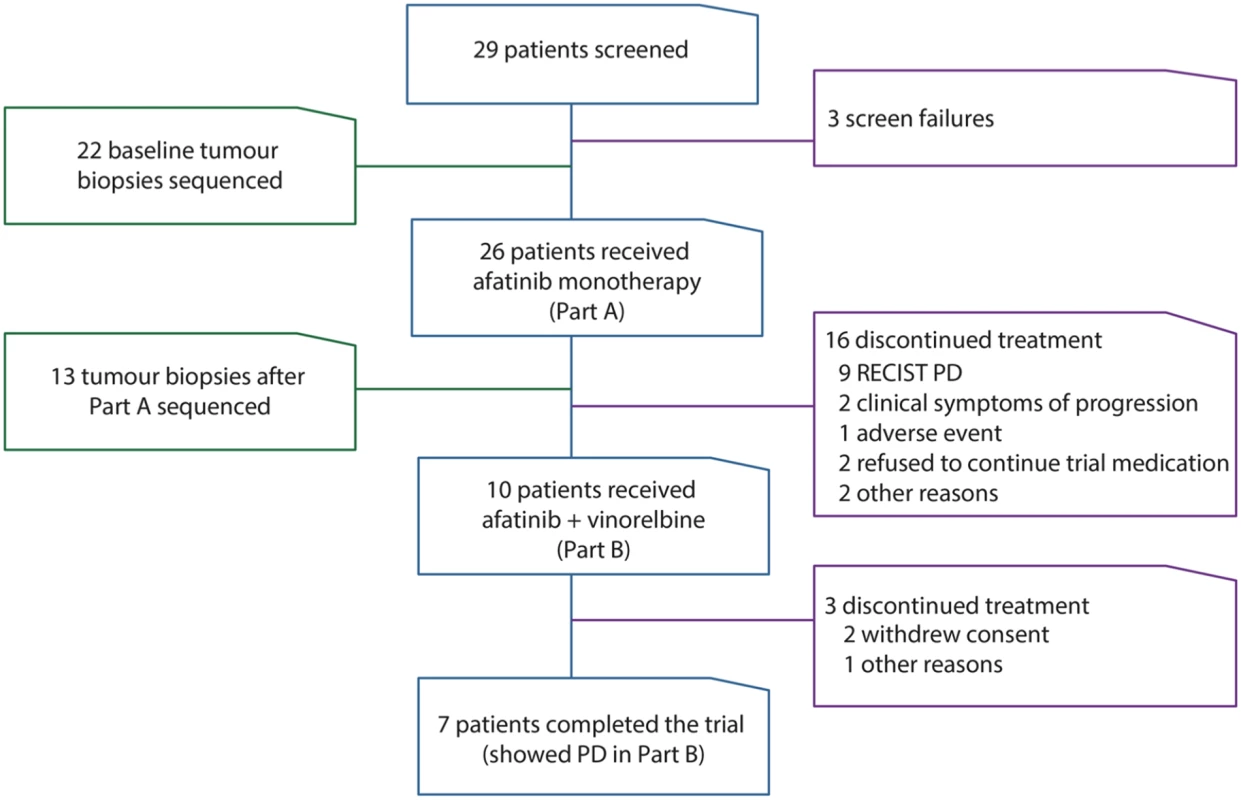

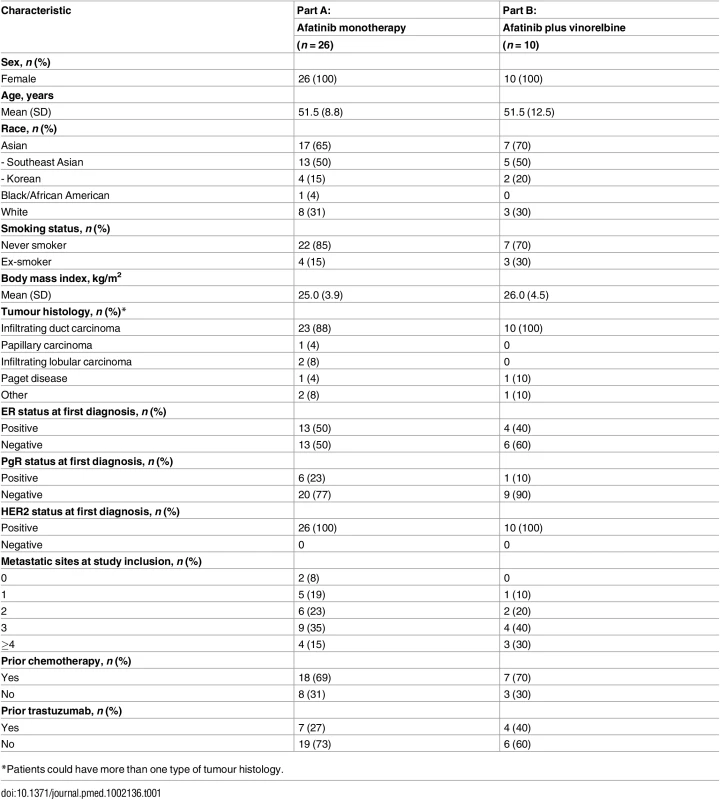

The study was performed at 14 centres in seven countries between December 2011 and November 2014. Twenty-nine patients were screened, and 26 received afatinib monotherapy; of these, 10 patients continued into Part B of the study (Fig 1). Twenty-four of 26 patients had metastatic disease at study inclusion. Patient demographics at baseline are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Study flow and patient disposition.

This figure describes the study and number of patients in each part of the clinical trial (blue outline), reasons for patients being excluded or discontinuing treatment (purple outline), and number of patients with genomic analysis performed (green outline). PD, progressive disease. Tab. 1. Patient demographics at beginning of study.

*Patients could have more than one type of tumour histology. Efficacy with Afatinib (Part A)

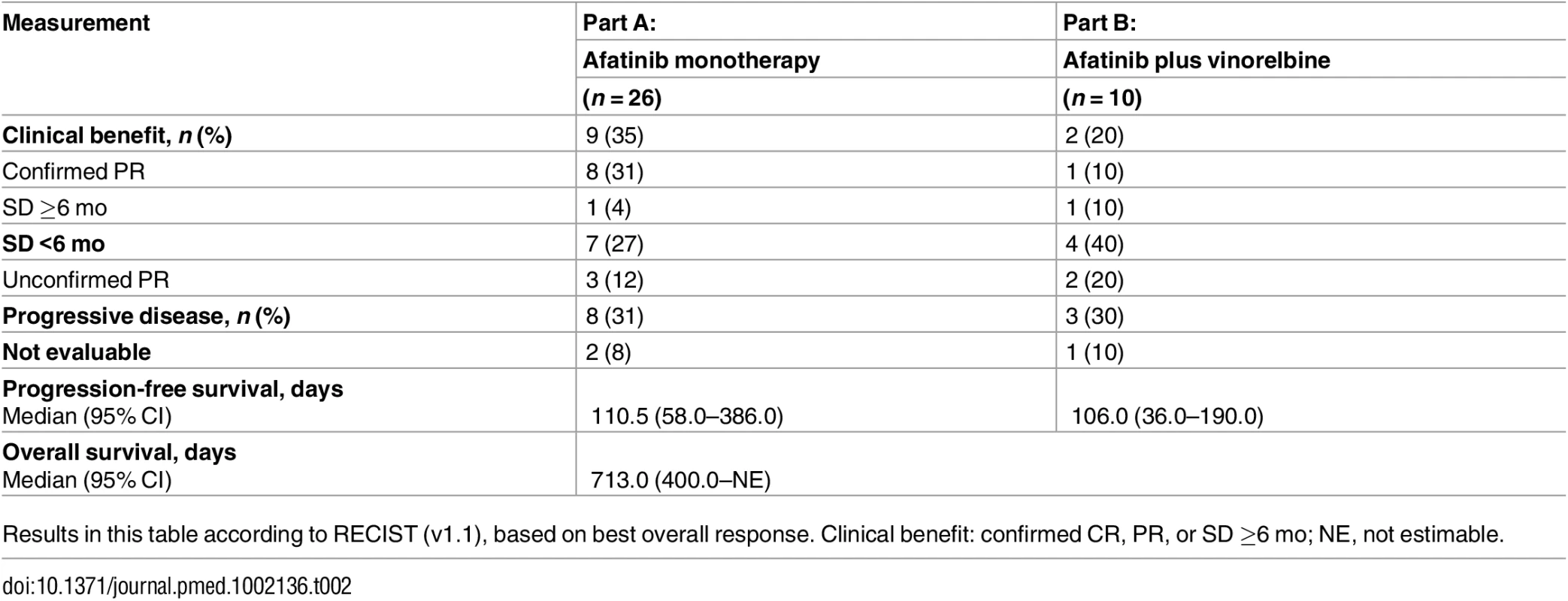

Nine (35%) of 26 treated patients had confirmed clinical benefit with afatinib monotherapy (eight PRs and one SD of ≥6 months; Table 2, S5 Table). Three patients had an unconfirmed PR, resulting in an overall response rate (ORR) of 42% (n = 11). Twenty (77%) patients progressed or died on afatinib monotherapy; median PFS was 110.5 days (95% CI 58.0–386.0). In total, there were three on-treatment and one post-study deaths. Planned subgroup analyses were performed (S1 Fig). Clinical benefit with afatinib monotherapy was achieved in 0 of 7 trastuzumab-treated patients and 9 of 19 (47%) trastuzumab-naïve patients. Median PFS with afatinib monotherapy was apparently shorter in trastuzumab-treated patients versus trastuzumab-naïve patients (64 versus 151 days, p-value = 0.099, log-rank test; S2 Fig).

Tab. 2. Summary of efficacy in patients enrolled in clinical trial.

Results in this table according to RECIST (v1.1), based on best overall response. Clinical benefit: confirmed CR, PR, or SD ≥6 mo; NE, not estimable. Efficacy with Afatinib plus Vinorelbine (Part B)

Following progression on afatinib monotherapy, ten patients received afatinib plus vinorelbine (Part B). Confirmed clinical benefit was achieved in two (20%; Table 2, S5 Table, S1 Fig); a further two patients had an unconfirmed PR, with an overall CBR rate of 40% (n = 4). Eight (80%) patients progressed or died. Median duration of PFS was 106.0 d (95% CI 36.0–190.0).

OS was analysed across the whole study. Eleven (42%) patients died during the study, and median OS was 713.0 d. Median PFS across the whole study was shorter in trastuzumab-treated patients versus trastuzumab-naïve (136 versus 395 d, p-value = 0.024, log-rank test, S3 Fig).

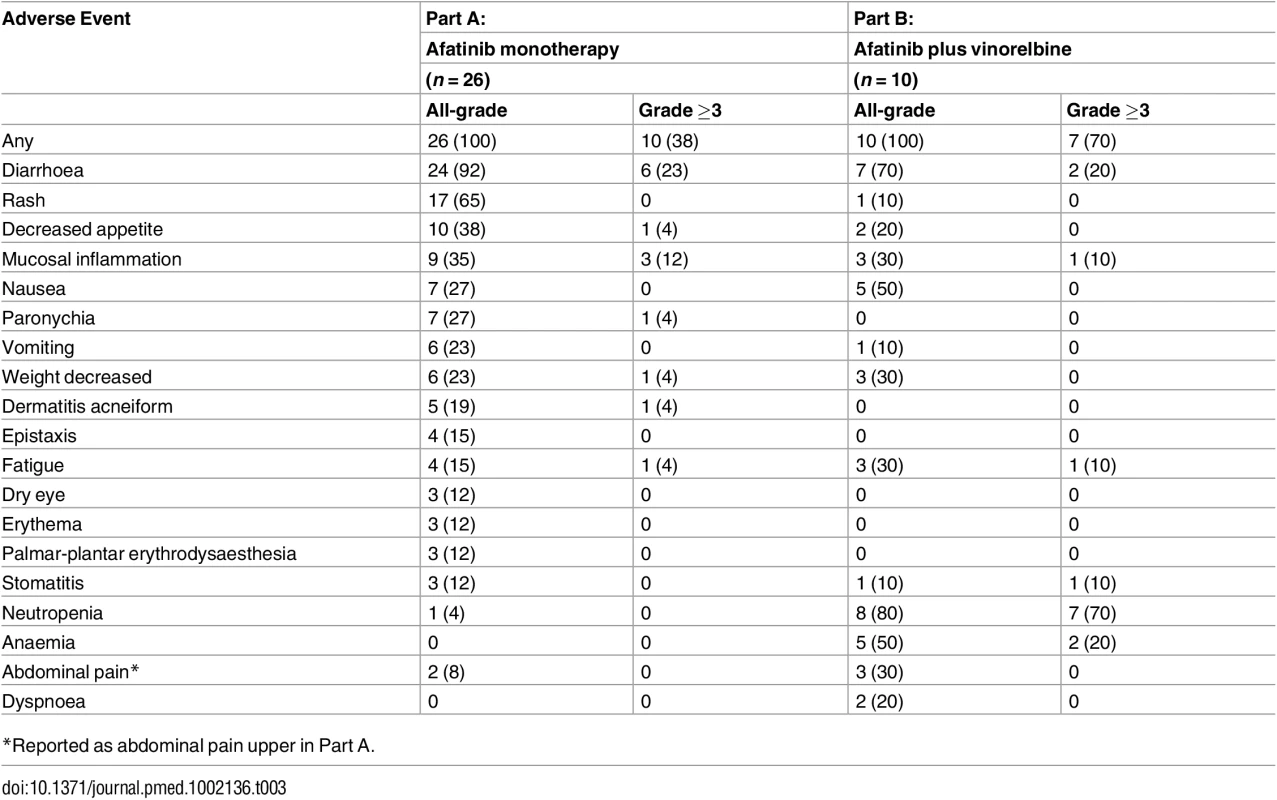

Safety

Median duration of exposure to treatment was 111 d (range: 17–700) in Part A and 84.5 d (range: 42–237) in Part B. All patients had treatment-related AEs (Table 3).

Tab. 3. Most common treatment-related adverse events reported in ≥10% of patients.

*Reported as abdominal pain upper in Part A. Mutational Landscape of HER2-Positive IBC

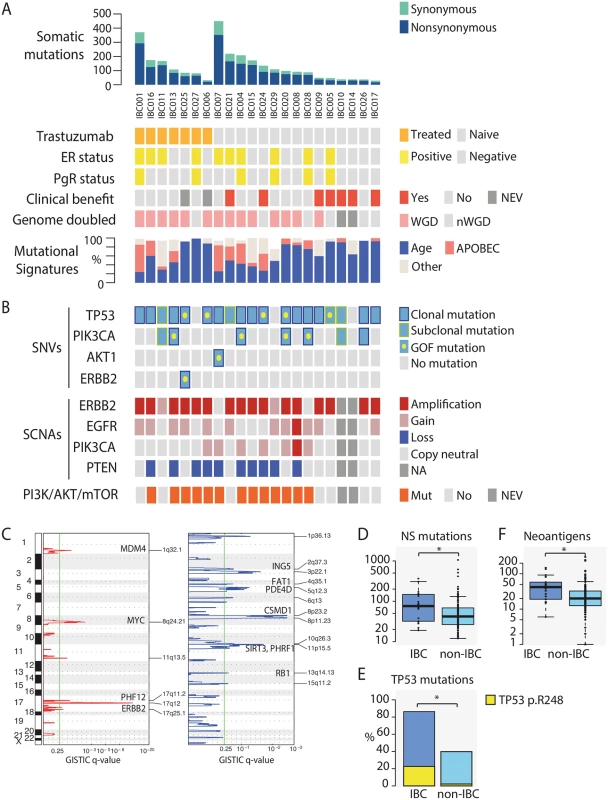

Twenty-two of 26 patients in Part A had tumour biopsy material suitable for whole-exome sequencing analysis (Fig 2). Overall, we identified an average of 134.5 (range: 30–468) somatic coding mutations (Fig 2A, S6 Table). The most commonly mutated gene was TP53 (MutSig q-value = 1.68x10-11); 86.4% (19/22) of the tumours harboured a somatic mutation in TP53 (S7 Table). Strikingly, five patients had gain-of-function TP53 mutations at hot-spot residue p.R248 (S4 Fig). Planned exploratory analyses showed that OS was non-significantly shorter in patients carrying TP53 p.R248 mutations pre-treatment versus those with loss-of-function (nonsense, frame-shift, splice site) mutations (398 versus 652 d, p-value = 0.626, log-rank test). Patients IBC007 and IBC001 had much higher numbers of somatic SNVs compared to the rest of the cohort (468 and 393, respectively) but did not have mutations in known DNA mismatch repair genes.

Fig. 2. Somatic mutations in HER2-positive IBC.

(A) Top panel shows number of somatic mutations (SNVs and indels) identified across the 22 IBC patients. Data tracks below indicate if patient was: treated with trastuzumab prior to afatinib monotherapy (orange); oestrogen-receptor (ER) or progesterone-receptor (PgR) positive (yellow); derived confirmed clinical benefit from afatinib monotherapy (red); tumour underwent whole-genome doubling (WGD) (pink). Mutational signatures identified in IBC tumours were predominantly age-related (Signatures 1A and 1B) (blue), APOBEC-related (Signatures 2 and 13) (salmon), and others (grey). NEV, not evaluated; NA, no information available. (B) TP53, PIK3CA, AKT1, and ERBB2 mutations identified in samples are indicated if present (blue) or absent (grey). Gain-of-function mutations (TP53 p.R248, PIK3CA p.H1047R, AKT1 p.E17K, ERBB2 p.V777L) are indicated by a yellow dot. Clonal and subclonal mutations are indicated by dark blue and yellow outlines, respectively. Amplifications (≥2x ploidy), gains (≥1 copy number relative to ploidy), and losses (≤1 copy number relative to ploidy) in ERBB2 (HER2), PIK3CA, EGFR, and PTEN are indicated by red, pink, and dark blue, respectively. Somatic activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (defined as PIK3CA activating mutation or gain, PTEN deletion, AKT1 mutation) indicated in orange. (C) Plots showing results of GISTIC analysis identifying recurrent focal gains (left panel in red) and losses (right panel in blue); y-axis is genomic position and x-axis is GISTIC q-value; green line represents significance threshold (q-value = 0.25). Gene names are indicated where significantly mutated cancer driver genes were previously associated with the GISTIC peak in a pan-cancer analysis of SCNAs [38]. (D) Box plot showing higher numbers of somatic nonsynonymous (NS) mutations identified in IBC patients compared to non-IBC patients. The band inside the box denotes median. (E) Bar plot showing an enrichment of TP53 mutations in IBC patients versus non-IBC patients. Yellow bar is proportion of gain-of-function TP53 p.R248 mutations. (F) Boxplot showing higher numbers of neoantigens predicted in IBC patients compared to non-IBC patients. Asterisk (*) denotes significant p-value <0.05. Mutations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are frequent in breast cancer, and activation of this pathway via molecular aberrations in PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3R1, AKT, TSC1/2, and PTEN promotes resistance to HER2-targeted therapies [39–41]. Seven patients harboured PIK3CA mutations, including four with hotspot mutation p.H1047R [42]. IBC007 harboured an activating AKT1 p.E17K mutation, and IBC025 carried an activating ERBB2 p.V777L mutation (Fig 2B) [43,44]. No other somatic mutations in this pathway were identified.

In order to gain insight into the mutational processes shaping the IBC landscape, we utilized previously extracted mutational signatures and applied them to the IBC cohort (Fig 2A, S5A Fig) [29,30]. Signature 1A, which was previously associated with age of diagnosis [45], accounted for the majority of mutations (64.2% ± 26.1). Signatures 2 and 13, attributed to activity of the APOBEC family of cytidine deaminases, were together present in 64% (14/22) of tumours (16.4% ± 19.7% of somatic mutations). In particular, the excess of mutations in IBC001 and IBC007 appear to be driven by APOBEC mutagenesis (S5B Fig), which was observed in both clonal and subclonal mutations for these samples (S5C Fig).

SCNA calling was possible in 20 of 22 tumours (S8 Table). Seventy percent (14/20) of the tumours had undergone whole-genome doubling and had higher genomic instability scores (wGII) compared to non-genome-doubled tumours (0.54 ± 0.18 versus 0.31 ± 0.06, p-value = 4.6x10-3, Mann-Whitney) (Fig 2A). Even though all IBC patients were HER2-positive via IHC or FISH (S1 Table), only 16 of 20 tumours were called as having ERBB2 amplification; two tumours (IBC011 and IBC029) harboured gains and two tumours (IBC007 and IBC028) had neither amplification nor gain of ERBB2 (Fig 2B). It is possible that these four tumours could represent false negatives due to reasons such as sampling bias caused by intra-tumour heterogeneity or normal tissue contamination. Sixty percent (12/20) of tumours had EGFR gains (11 gains, 1 amplification), consistent with previous reports [8]; 10 tumours had PTEN loss (Fig 2B). GISTIC [25] analysis revealed recurrent focal amplifications across 6 loci, including 17q12 (q-value = 9.22x10-13), 8q24.21 (q-value = 4.89x10-3), and 1q32.1 (q-value = 5.80x10-2) containing ERBB2, MYC, and MDM4, respectively (Fig 2C, S9 Table). Recurrent focal losses were identified across 12 chromosomal regions, including 11p5.15 (q-value = 2.09x10-2) containing SIRT3 and PHRF1.

We carried out planned exploratory analyses to identify predictive markers of response and resistance to afatinib. We did not identify an association between EGFR gains or HER2 amplifications and response to afatinib. Since activation of PI3K/Akt signalling is thought to impact the efficacy of HER2-targeted treatment [46–48], we focused on mutations in this pathway to explore any potential impact on PFS. We observed that somatic activation of this pathway (i.e. PIK3CA activating mutation or gain, ERBB2 activating mutation, PTEN deletion, AKT1 activating mutation) was significantly associated with shorter PFS in trastuzumab-naïve patients (p-value = 0.03, S6 Fig). Although activating mutations of the PI3K pathway have been reported as occurring more frequently in ER-positive breast tumours [40], we did not observe a difference in this small cohort (6/10 ER-positive versus 7/12 ER-negative). Unexpectedly, a trastuzumab-naïve patient (IBC024) harbouring a gain overlapping PIK3CA and PTEN heterozygous deletion at baseline showed a PR for 48 wk before disease progression.

Genomic Analysis of HER2-Positive IBC versus HER2-Positive non-IBC

To determine if there were significant differences in mutational profiles between HER2-positive IBC and HER2-positive non-IBC, we compared our results against a cohort of TCGA patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (n = 131, S4 Table) [36]. We observed that the average number of somatic protein-changing mutations per patient was higher in IBC than non-IBC patients (102.4 ± 89.4 versus 71.9 ± 115.3; p-value = 0.0107, Mann-Whitney) (Fig 2D).

Given that TP53 was the only significantly mutated gene identified in IBC, we compared the mutation burden of this gene between the 2 cohorts. We observed that TP53 mutations were significantly enriched in the IBC cohort compared to non-IBC (19/22 versus 53/131; p-value = 5.76x10-5, Fisher’s exact) [49], as were TP53 hotspot p.R248 mutations (5/19 versus 3/53; p-value = 0.026, Fisher’s exact) (Fig 2E). Consistent with the higher mutational load, IBC tumours also had a higher number of predicted neoantigens compared to non-IBC (49.59 ± 37.9 versus 31.0 ± 41.8, p-value = 8.39x10-4, Mann-Whitney) (Fig 2F). Similar to IBC, the most prevalent mutational processes among the non-IBC cohort were age and APOBEC-related, with similar distributions of these mutational signatures between the 2 cohorts (S5D Fig).

There were no significant differences in the proportion of genome-doubled tumours (14/20 versus 75/131, p-value = 0.34, Fisher’s exact) or wGII scores (0.47 versus 0.51, p-value = 0.3843, Mann-Whitney) between IBC and non-IBC tumours. Applying GISTIC to the non-IBC tumours, 5 of 6 recurrently amplified regions and all 12 recurrently deleted regions in IBC had wide-peak boundaries that overlapped with those of non-IBC tumours (S9 Table). Only the 11q13.5 amplification in IBC did not overlap with non-IBC, which includes PAK1, an oncogene that activates MAPK and MET signalling and regulates cell motility; interestingly, previous reports have associated IBC with MAPK hyperactivation [50,51].

Utilizing an age and ER/PgR status matched cohort (Methods), the results were concordant, with a higher burden of somatic protein-changing mutations, neoantigens, and TP53 mutations in IBC versus non-IBC (S7 Fig).

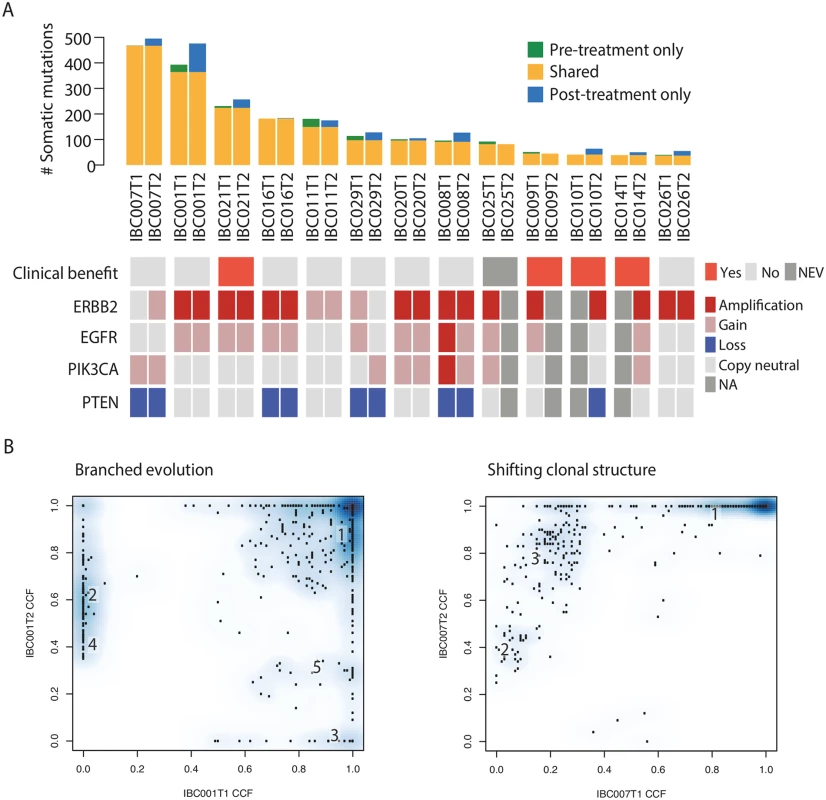

Tracking Genomic Evolution of Afatinib Treated IBC

Among 13 tumour biopsies obtained following disease progression, we identified an average of 181.4 (range: 50–505) somatic mutations, of which 79.1% ± 12.0% were shared with baseline tumours (Fig 3A, S10 Table). The overall mutation burden in tumours following treatment was higher in post-treatment samples compared to pre-treatment samples (172.5 ± 136.7 versus 156.1 ± 151.9, p-value = 0.030, paired t test). No recurrent mutations were identified among newly arising mutations post-treatment, and no new mutations in PI3K/Akt pathway genes were identified, aside from a MTOR p.K30N mutation (variant of unknown significance) in IBC021.

Fig. 3. Genomic analysis of tumour biopsies before treatment and following disease progression on afatinib monotherapy.

(A) Somatic mutations (SNVs and indels) identified in pre- and post-treatment biopsies. Green, mutations identified in pre-treatment only; yellow, mutations identified in both pre- and post-treatment; blue, mutations identified in post-treatment only. Data tracks below denote: if patient derived confirmed clinical benefit from afatinib monotherapy (red); amplifications (≥2x ploidy), gains (≥1 copy number relative to ploidy), and losses (≤1 copy number relative to ploidy) in ERBB2 (HER2), EGFR, PIK3CA, and PTEN are indicated by red, pink, and blue, respectively. NEV, not evaluated; NA, no information available. (B) Two main patterns of clonal evolution following afatinib monotherapy observed, either branched evolution or shifting clonal structure. Numbers refer to mutation clusters from PyClone results, also in S10 Fig. T1, pre-treatment biopsy; T2, post-treatment biopsy; CCF, cancer cell fraction. Nine of 13 matched pairs had copy number data (S11 Table); all tumours had the same genome-doubling status pre - and post-treatment, and there was no difference in ploidy (2.9 versus 2.9, p-value = 0.80) or wGII scores (0.42 versus 0.46, p-value = 0.55) (S8 Fig, S3 Table) between pre - and post-treatment samples. ERBB2 amplification status appeared to change in two of nine patients, from gain to copy-neutral in IBC029 and from copy-neutral to gain in IBC007 (Fig 3A). Overall, SCNAs between paired samples (n = 9) were highly concordant, and unsupervised hierarchical clustering showed that tumour biopsies clustered by patient rather than treatment stage (S9 Fig).

Drug resistance may arise as a consequence of an evolutionary bottleneck, where a resistant subclone is selectively enriched during therapy [52]. We utilized previously described methods to compare the clonal architecture of tumours before and after treatment [32,53]. Of these nine patients, IBC021 was the only patient with confirmed clinical benefit. We observed in all patients a cluster of variants that was clonal in both pre - and post-treatment biopsies (cancer cell fraction [CCF] around 1.0 on both x and y axis in S10 Fig); all gain-of-function PIK3CA and TP53 mutations, when present in the tumour, belonged to this cluster. In eight of nine patients, we observed some evidence of branching evolution, with new clones identifiable in the post-treatment samples and others declining in frequency or disappearing (Fig 3B, S11 Fig). Interestingly, the majority of mutations identified after treatment were detected in the pre-treatment tumour biopsy at a similar CCF (S10 and S11 Figs), and the overall clonal composition in all 8 tumours remained largely similar between the two time points with little evidence of bottlenecking, consistent with the lack of confirmed benefit in these patients, aside from IBC021. In one patient (IBC007), new clones were not observed, but there were distinct clonal shifts; there was clonal expansion of two subclones from 2% to 38% and 22% to 81%, and the major clone decreased slightly from 96% to 78%; no known drivers were identified in the subclones (S10 Table). Importantly, we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed dynamics could be due to tumour sampling bias between pre - and post-treatment samples.

Discussion

Longitudinal analysis of the genomic evolution of tumours during therapy can inform drug resistance mechanisms and the changing landscape of disease over time. Here, we report the first prospectively planned clinical trial in IBC with genomic analysis, and the first assessment of afatinib with or without vinorelbine in patients with HER2-positive IBC.

Afatinib monotherapy demonstrated activity in patients with HER2-positive IBC, with nine (35%) patients achieving clinical benefit and median PFS of 110.5 d. This is concordant with data from a phase II trial assessing lapatinib 1500 mg daily in 126 patients with relapsed or refractory HER2-positive IBC, in which no patients had a CR but 49 (39%) had a PR and median PFS was 102.2 d [54]. Following progression on afatinib monotherapy, two (20%) patients achieved clinical benefit with addition of vinorelbine, and median PFS in Part B was 106.0 d.

The most common treatment-related events reported during the trial were diarrhoea, rash, and decreased appetite in Part A, and neutropenia, diarrhoea, nausea, and anaemia in Part B. Overall, the safety profile observed was generally consistent with previously published data on afatinib and vinorelbine. Importantly, this trial included pre-planned exome analysis of tumour biopsies at two time-points: before treatment and at disease progression. To our knowledge, this is the first report characterising IBC through exome sequencing. We identified a high incidence of TP53 mutations, as reported previously [49], and an enrichment of p.R248 hotspot DNA-contact mutations that promote nuclear accumulation of p53 [55–57]; cellular and animal studies indicate that these gain-of-function mutations induce increased invasion, chemoresistance and decreased survival [58–60]. Our results showed a non-significant reduction in OS in IBC patients carrying TP53 p.R248 mutations, consistent with previous analysis [61] and reports of nuclear p53 overexpression representing an adverse prognostic marker in IBC [62–64].

We identified recurrent focal gains across 6 loci and losses across 12 regions, including 11p5.15 containing SIRT3 and PHRF1 (also identified in the non-IBC cohort). SIRT3 is deleted in 40% of human breast tumours, and loss of SIRT3 increases reactive oxygen species production and HIF-1a stabilization [65]. PHRF1 functions as a tumour suppressor by promoting the TGF-beta cytostatic programme [66]; a recent transcriptomic study identified reduced TGF-beta signalling as a specific gene expression signature of IBC compared to non-IBC [67]. Comparing IBC to non-IBC, the only different recurrent focal SCNA was the amplification of 11q13.5 containing PAK1 in IBC; PAK1 is an oncogene that activates MAPK and MET signalling and regulates cell motility, and previous reports have associated IBC with MAPK hyperactivation [50,51].

We compared tumours before and after afatinib monotherapy to investigate potential drivers of resistance. The tumour pairs displayed a high degree of genetic relatedness, both in terms of point mutations and large-scale genomic aberrations. We did not observe changes in ERBB2 amplification status in the majority (7/9 or 78%) of our tumours, consistent with previous reports of loss of HER2-positivity occurring in only 12%–32% of patients undergoing anti-HER2 therapy [68–71]. In the two patients who appeared to undergo a change in amplification status, we are unable to conclude if the lack of ERBB2 amplification (in the pre-treatment biopsy for IBC007 and in the post-treatment biopsy for IBC029) was due to technical limitations of exome sequencing, sampling bias, or selection of a HER2-negative subclone during therapy (in the case of IBC029).

In contrast to EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinomas, in which the T790M gatekeeper mutation is commonly selected following EGFR inhibitor exposure [72], there was no evidence of selection for mutations in specific genes in the post-treatment IBC tumours. Eight out of 9 tumour pairs displayed branching evolution, with new clones emerging and others disappearing after treatment, possibly reflecting the differential effect that afatinib monotherapy had on the different subclones; it is worth noting that only 1 of 8 of these patients (IBC021) derived confirmed clinical benefit from afatinib monotherapy. It is also possible that subclones detected only in the pre - or post-treatment tumour biopsy in this study could be related to sampling bias or caused by the “illusion of clonality” derived from a single-region biopsy. Regardless, the majority of mutations in these tumours were shared between the two time points and possessed largely similar clonal compositions, concordant with previous reports in pre - and post-treatment samples of multiple myeloma and high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma [53,73]. IBC007 was the only tumour with an apparent shift in clonal structure, possibly reflecting random drift of tumour clones or sampling bias, given that this patient did not respond to afatinib monotherapy [32,53]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been shown to provide clinical benefit in a variety of cancers, including melanoma and lung cancer [74–77]. In particular, a high mutational load (>100 somatic nonsynonymous coding mutations) was reported as significantly correlated with improved OS in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab or tremelimumab [78]. Several clinical trials investigating the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors have already been initiated in HER2-positive breast cancer (NCT02734004, NCT02605915, NCT02318901, NCT02403271) and HER2-positive gastric cancer (NCT02689284). The mutational burden in our study revealed an average of 102.4 nonsynonymous mutations in baseline HER2-positive IBC, above the threshold indicated for clinical benefit with anti-CTLA4 therapy [78]. The high mutational and neoantigenic load associated with HER2-positive IBC suggests a potential role for checkpoint inhibitor therapy in this disease.

Following the results of the LUX-Breast 1 trial, recruitment to this study was terminated early. As such, a limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size of HER2-positive IBC patients, making it difficult to draw robust conclusions regarding clinical efficacy of afatinib in this disease. Furthermore, single-region biopsies could be leading to underestimation of tumoural heterogeneity and clonal dynamics.

In conclusion, this phase II trial demonstrated that afatinib, with or without vinorelbine, showed activity in patients with HER2-positive IBC in trastuzumab-naïve patients, albeit in a small patient cohort. This is one of the first clinical trials to fully and prospectively integrate longitudinal exome sequencing with drug development. HER2-positive IBC is characterised by a higher mutational and neoantigenic burden and greater incidence of TP53 mutations compared to HER2-positive non-IBC. PI3K pathway activation was associated with poorer outcomes on afatinib therapy. Analysis of pre - and post-afatinib monotherapy tumour biopsies did not identify major dynamics of tumour sublcones or recurrent somatic mutations driving resistance. Epigenetic and tumour microenvironmental changes [79,80] may contribute to drug resistance in IBC and should be investigated further in future trials.

This study provides a proof of principle that prospective planning of genomic analysis in clinical trials is feasible in advanced breast cancer, and provides insight into the dynamics of cancer genome evolution through therapy.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Anderson WF, Schairer C, Chen BE, Hance KW, Levine PH. Epidemiology of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). Breast Dis. 2005;22 : 9–23. 16735783

2. Gunhan-Bilgen I, Ustun EE, Memis A. Inflammatory breast carcinoma: mammographic, ultrasonographic, clinical, and pathologic findings in 142 cases. Radiology. 2002;223(3):829–38. 12034956

3. Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine PH. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(13):966–75. 15998949

4. Mejri N, Boussen H, Labidi S, Bouzaiene H, Afrit M, Benna F, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer in Tunisia from 2005 to 2010: epidemiologic and anatomoclinical transitions from published data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(3):1277–80. 25735367

5. Low JA, Berman AW, Steinberg SM, Danforth DN, Lippman ME, Swain SM. Long-term follow-up for locally advanced and inflammatory breast cancer patients treated with multimodality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4067–74. 15483018

6. van Uden DJ, van Laarhoven HW, Westenberg AH, de Wilt JH, Blanken-Peeters CF. Inflammatory breast cancer: an overview. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;93(2):116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.09.003 25459672

7. Robertson FM, Bondy M, Yang W, Yamauchi H, Wiggins S, Kamrudin S, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: the disease, the biology, the treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(6):351–75. doi: 10.3322/caac.20082 20959401

8. Cabioglu N, Gong Y, Islam R, Broglio KR, Sneige N, Sahin A, et al. Expression of growth factor and chemokine receptors: new insights in the biology of inflammatory breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(6):1021–9. 17351259

9. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Vermeulen P, Van Dam P, Dirix L, Birnbaum D, et al. Genomic profiling of inflammatory breast cancer: a review. Breast. 2014;23(5):538–45. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.06.008 24998451

10. Iwamoto T, Bianchini G, Qi Y, Cristofanilli M, Lucci A, Woodward WA, et al. Different gene expressions are associated with the different molecular subtypes of inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(3):785–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1280-6 21153052

11. Ross JS, Ali SM, Wang K, Khaira D, Palma NA, Chmielecki J, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of inflammatory breast cancer cases reveals a high frequency of clinically relevant genomic alterations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154(1):155–62. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3592-z 26458824

12. Zhang D, LaFortune TA, Krishnamurthy S, Esteva FJ, Cristofanilli M, Liu P, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor reverses mesenchymal to epithelial phenotype and inhibits metastasis in inflammatory breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(21):6639–48. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0951 19825949

13. Lin NU, Winer EP, Wheatley D, Carey LA, Houston S, Mendelson D, et al. A phase II study of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible ErbB family blocker, in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer progressing after trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1057–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2003-y 22418700

14. Rimawi MF, Aleixo SB, Rozas AA, Nunes de Matos Neto J, Caleffi M, Figueira AC, et al. A neoadjuvant, randomized, open-label phase II trial of afatinib versus trastuzumab versus lapatinib in patients with locally advanced HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15(2):101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.11.004 25537159

15. Harbeck N, Huang CS, Hurvitz S, Yeh DC, Shao Z, Im SA, et al. Afatinib plus vinorelbine versus trastuzumab plus vinorelbine in patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer who had progressed on one previous trastuzumab treatment (LUX-Breast 1): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016 Mar;17(3):357–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00540-9 Epub 2016 Jan 26 26822398

16. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 19451168

17. DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):491–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.806 21478889

18. Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22(3):568–76. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111 22300766

19. Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):213–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514 23396013

20. Kim S, Jeong K, Bhutani K, Lee J, Patel A, Scott E, et al. Virmid: accurate detection of somatic mutations with sample impurity inference. Genome Biol. 2013;14(8):R90. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r90 23987214

21. Saunders CT, Wong WS, Swamy S, Becq J, Murray LJ, Cheetham RK. Strelka: accurate somatic small-variant calling from sequenced tumor-normal sample pairs. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(14):1811–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts271 22581179

22. Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(21):2865–71. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394 19561018

23. Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 22588877

24. Van Loo P, Nordgard SH, Lingjaerde OC, Russnes HG, Rye IH, Sun W, et al. Allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(39):16910–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009843107 20837533

25. Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12(4):R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41 21527027

26. Murugaesu N, Wilson GA, Birkbak NJ, Watkins TB, McGranahan N, Kumar S, et al. Tracking the genomic evolution of esophageal adenocarcinoma through neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(8):821–31. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0412 26003801

27. Dewhurst SM, McGranahan N, Burrell RA, Rowan AJ, Gronroos E, Endesfelder D, et al. Tolerance of whole-genome doubling propagates chromosomal instability and accelerates cancer genome evolution. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(2):175–85. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0285 24436049

28. Burrell RA, McClelland SE, Endesfelder D, Groth P, Weller MC, Shaikh N, et al. Replication stress links structural and numerical cancer chromosomal instability. Nature. 2013;494(7438):492–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11935 23446422

29. Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Taylor BS, Swanton C. deconstructSigs: delineating mutational processes in single tumors distinguishes DNA repair deficiencies and patterns of carcinoma evolution. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):31.

30. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415–21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477 23945592

31. McGranahan N, Favero F, de Bruin EC, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z, Swanton C. Clonal status of actionable driver events and the timing of mutational processes in cancer evolution. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(283):283ra54. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1408 25877892

32. Roth A, Khattra J, Yap D, Wan A, Laks E, Biele J, et al. PyClone: statistical inference of clonal population structure in cancer. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):396–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2883 24633410

33. McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, Ramskov S, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016;351(6280):1463–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1490 26940869

34. Szolek A, Schubert B, Mohr C, Sturm M, Feldhahn M, Kohlbacher O. OptiType: precision HLA typing from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(23):3310–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu548 25143287

35. Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M. NetMHC-3.0: accurate web accessible predictions of human, mouse and monkey MHC class I affinities for peptides of length 8–11. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W509–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn202 18463140

36. Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH, Wilkerson MD, Rhie SK, Pastore A, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Portraits of Invasive Lobular Breast Cancer. Cell. 2015;163(2):506–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033 26451490

37. Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499(7457):214–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12213 23770567

38. Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1134–40. doi: 10.1038/ng.2760 24071852

39. Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(8):627–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926 19644473

40. Miller TW, Rexer BN, Garrett JT, Arteaga CL. Mutations in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway: role in tumor progression and therapeutic implications in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(6):224. doi: 10.1186/bcr3039 22114931

41. Polivka J Jr., Janku F. Molecular targets for cancer therapy in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142(2):164–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.004 24333502

42. Gymnopoulos M, Elsliger MA, Vogt PK. Rare cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA show gain of function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(13):5569–74. 17376864

43. Bose R, Kavuri SM, Searleman AC, Shen W, Shen D, Koboldt DC, et al. Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(2):224–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0349 23220880

44. Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, Donoho GP, Briggs SL, Robbins CM, et al. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7152):439–44. 17611497

45. Alexandrov LB, Jones PH, Wedge DC, Sale JE, Campbell PJ, Nik-Zainal S, et al. Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat Genet. 2015;47(12):1402–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.3441 26551669

46. Chandarlapaty S, Sakr RA, Giri D, Patil S, Heguy A, Morrow M, et al. Frequent mutational activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(24):6784–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1785 23092874

47. Lavaud P, Andre F. Strategies to overcome trastuzumab resistance in HER2-overexpressing breast cancers: focus on new data from clinical trials. BMC Med. 2014;12 : 132. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0132-3 25285786

48. Rexer BN, Arteaga CL. Intrinsic and acquired resistance to HER2-targeted therapies in HER2 gene-amplified breast cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Crit Rev Oncog. 2012;17(1):1–16. 22471661

49. Turpin E, Bieche I, Bertheau P, Plassa LF, Lerebours F, de Roquancourt A, et al. Increased incidence of ERBB2 overexpression and TP53 mutation in inflammatory breast cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21(49):7593–7. 12386822

50. van Golen KL, Bao LW, Pan Q, Miller FR, Wu ZF, Merajver SD. Mitogen activated protein kinase pathway is involved in RhoC GTPase induced motility, invasion and angiogenesis in inflammatory breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19(4):301–11. 12090470

51. Van Laere SJ, Van der Auwera I, Van den Eynden GG, van Dam P, Van Marck EA, Vermeulen PB, et al. NF-kappaB activation in inflammatory breast cancer is associated with oestrogen receptor downregulation, secondary to EGFR and/or ErbB2 overexpression and MAPK hyperactivation. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(5):659–69. 17700572

52. Gerlinger M, Swanton C. How Darwinian models inform therapeutic failure initiated by clonal heterogeneity in cancer medicine. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(8):1139–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605912 20877357

53. Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Alexandrov LB, Martincorena I, et al. Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2014;5 : 2997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3997 24429703

54. Kaufman B, Trudeau M, Awada A, Blackwell K, Bachelot T, Salazar V, et al. Lapatinib monotherapy in patients with HER2-overexpressing relapsed or refractory inflammatory breast cancer: final results and survival of the expanded HER2+ cohort in EGF103009, a phase II study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(6):581–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70087-7 19394894

55. Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265(5170):346–55. 8023157

56. Oren M, Rotter V. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(2):a001107. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001107 20182618

57. Zheng T, Wang J, Zhao Y, Zhang C, Lin M, Wang X, et al. Spliced MDM2 isoforms promote mutant p53 accumulation and gain-of-function in tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2013;4 : 2996. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3996 24356649

58. Brachova P, Thiel KW, Leslie KK. The consequence of oncomorphic TP53 mutations in ovarian cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(9):19257–75. doi: 10.3390/ijms140919257 24065105

59. Hanel W, Marchenko N, Xu S, Yu SX, Weng W, Moll U. Two hot spot mutant p53 mouse models display differential gain of function in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(7):898–909. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.17 23538418

60. Song H, Hollstein M, Xu Y. p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(5):573–80. 17417627

61. Xu J, Wang J, Hu Y, Qian J, Xu B, Chen H, et al. Unequal prognostic potentials of p53 gain-of-function mutations in human cancers associate with drug-metabolizing activity. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1108. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.75 24603336

62. Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Sneige N, Buzdar AU, Valero V, Kau SW, Broglio K, et al. p53 expression as a prognostic marker in inflammatory breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(18 Pt 1):6215–21. 15448010

63. Riou G, Le MG, Travagli JP, Levine AJ, Moll UM. Poor prognosis of p53 gene mutation and nuclear overexpression of p53 protein in inflammatory breast carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(21):1765–7. 8411261

64. Saydam BK, Goksel G, Korkmaz E, Zekioglu O, Kapkac M, Sanli UA, et al. Comparison of inflammatory breast cancer and noninflammatory breast cancer in Western Turkey. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(6):475–80. doi: 10.1159/000151570 18836277

65. Finley LW, Carracedo A, Lee J, Souza A, Egia A, Zhang J, et al. SIRT3 opposes reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism through HIF1alpha destabilization. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(3):416–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.014 21397863

66. Ettahar A, Ferrigno O, Zhang MZ, Ohnishi M, Ferrand N, Prunier C, et al. Identification of PHRF1 as a tumor suppressor that promotes the TGF-beta cytostatic program through selective release of TGIF-driven PML inactivation. Cell Rep. 2013;4(3):530–41. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.009 23911286

67. Van Laere SJ, Ueno NT, Finetti P, Vermeulen P, Lucci A, Robertson FM, et al. Uncovering the molecular secrets of inflammatory breast cancer biology: an integrated analysis of three distinct affymetrix gene expression datasets. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(17):4685–96. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2549 23396049

68. Burstein HJ, Harris LN, Gelman R, Lester SC, Nunes RA, Kaelin CM, et al. Preoperative therapy with trastuzumab and paclitaxel followed by sequential adjuvant doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide for HER2 overexpressing stage II or III breast cancer: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):46–53. 12506169

69. Harris LN, You F, Schnitt SJ, Witkiewicz A, Lu X, Sgroi D, et al. Predictors of resistance to preoperative trastuzumab and vinorelbine for HER2-positive early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(4):1198–207. 17317830

70. Mittendorf EA, Wu Y, Scaltriti M, Meric-Bernstam F, Hunt KK, Dawood S, et al. Loss of HER2 amplification following trastuzumab-based neoadjuvant systemic therapy and survival outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7381–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1735 19920100

71. Niikura N, Liu J, Hayashi N, Mittendorf EA, Gong Y, Palla SL, et al. Loss of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression in metastatic sites of HER2-overexpressing primary breast tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(6):593–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8889 22124109

72. Godin-Heymann N, Ulkus L, Brannigan BW, McDermott U, Lamb J, Maheswaran S, et al. The T790M "gatekeeper" mutation in EGFR mediates resistance to low concentrations of an irreversible EGFR inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(4):874–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2387 18413800

73. Castellarin M, Milne K, Zeng T, Tse K, Mayo M, Zhao Y, et al. Clonal evolution of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma from primary to recurrent disease. J Pathol. 2013;229(4):515–24. doi: 10.1002/path.4105 22996961

74. Brahmer JR. Immune checkpoint blockade: the hope for immunotherapy as a treatment of lung cancer? Semin Oncol. 2014;41(1):126–32. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.12.014 24565586

75. Creelan BC. Update on immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Control. 2014;21(1):80–9. 24357746

76. Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, Kluger HM, Carvajal RD, Sharfman WH, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1020–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0105 24590637

77. Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369 23724867

78. Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498 25409260

79. Andre F, Berrada N, Desmedt C. Implication of tumor microenvironment in the resistance to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(6):547–51. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833fb384 20842030

80. Karn T, Pusztai L, Rody A, Holtrich U, Becker S. The Influence of Host Factors on the Prognosis of Breast Cancer: Stroma and Immune Cell Components as Cancer Biomarkers. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15(8):652–64. 26452382

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2016 Číslo 12- Berberin: přírodní hypolipidemikum se slibnými výsledky

- Léčba bolesti u seniorů

- Příznivý vliv Armolipidu Plus na hladinu cholesterolu a zánětlivé parametry u pacientů s chronickým subklinickým zánětem

- Červená fermentovaná rýže účinně snižuje hladinu LDL cholesterolu jako vhodná alternativa ke statinové terapii

- Jak postupovat při výběru betablokátoru − doporučení z kardiologické praxe

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Tumor Evolution in Two Patients with Basal-like Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Genomics Study of Multiple Metastases

- Expression of lncRNAs in Low-Grade Gliomas and Glioblastoma Multiforme: An In Silico Analysis

- Exploratory Analysis of Mutations in Circulating Tumour DNA as Biomarkers of Treatment Response for Patients with Relapsed High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study

- The Subclonal Architecture of Metastatic Breast Cancer: Results from a Prospective Community-Based Rapid Autopsy Program “CASCADE”

- Predictors of Chemosensitivity in Triple Negative Breast Cancer: An Integrated Genomic Analysis

- Histological Transformation and Progression in Follicular Lymphoma: A Clonal Evolution Study

- Somatic Genomics and Clinical Features of Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Retrospective Study

- Patterns of Immune Infiltration in Breast Cancer and Their Clinical Implications: A Gene-Expression-Based Retrospective Study

- IL-7 Receptor Mutations and Steroid Resistance in Pediatric T cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Genome Sequencing Study

- Cancer Genomics: Large-Scale Projects Translate into Therapeutic Advances

- Overcoming Steroid Resistance in T Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Precision Cancer Diagnostics: Tracking Genomic Evolution in Clinical Trials

- Immunotherapy in the Precision Medicine Era: Melanoma and Beyond

- Sequencing Strategies to Guide Decision Making in Cancer Treatment

- Blood-Based Analysis of Circulating Cell-Free DNA and Tumor Cells for Early Cancer Detection

- Base-Position Error Rate Analysis of Next-Generation Sequencing Applied to Circulating Tumor DNA in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Prospective Study

- Clonal Evolutionary Analysis during HER2 Blockade in HER2-Positive Inflammatory Breast Cancer: A Phase II Open-Label Clinical Trial of Afatinib +/- Vinorelbine

- Mutational Profile of Metastatic Breast Cancers: A Retrospective Analysis

- Genomic Analysis of Uterine Lavage Fluid Detects Early Endometrial Cancers and Reveals a Prevalent Landscape of Driver Mutations in Women without Histopathologic Evidence of Cancer: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genomic Analysis of Uterine Lavage Fluid Detects Early Endometrial Cancers and Reveals a Prevalent Landscape of Driver Mutations in Women without Histopathologic Evidence of Cancer: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study

- Overcoming Steroid Resistance in T Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Clonal Evolutionary Analysis during HER2 Blockade in HER2-Positive Inflammatory Breast Cancer: A Phase II Open-Label Clinical Trial of Afatinib +/- Vinorelbine

- Predictors of Chemosensitivity in Triple Negative Breast Cancer: An Integrated Genomic Analysis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání