-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaUFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

Protein modification by Ubiquitin (Ub) and Ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubl) plays pivotal roles in a wide range of cellular functions and signaling pathways. The Ufm1 conjugation system is a novel ubiquitin-like system, yet its biological functions and working mechanism remains poorly understood. UFBP1 is a putative Ufm1 target that has been implicated in several signaling pathways but little is known regarding its in vivo function. In this report, by using multiple knockout mouse models, we demonstrate that UFBP1 is essential for murine development and blood cell development. While germ-line deletion of UFBP1 caused defective red blood cell development and embryonic lethality, somatic ablation of UFBP1 impaired production of mature red blood cells and other types of hematopoietic cells. We found that depletion of UFBP1 led to elevated stress in the endoplasmic reticulum that in turn caused cell death of hematopoietic stem cells. Furthermore, UFBP1 deficiency diminished expression of key transcription factors essential for red blood cell development. Taken together, our study provides strong genetic evidence for the essential role of UFBP1 as well as other components of the Ufm1 system in hematopoietic development. Therefore, the ufmylation pathway may represent a novel therapeutic target in treatment of blood diseases.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005643

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005643Summary

Protein modification by Ubiquitin (Ub) and Ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubl) plays pivotal roles in a wide range of cellular functions and signaling pathways. The Ufm1 conjugation system is a novel ubiquitin-like system, yet its biological functions and working mechanism remains poorly understood. UFBP1 is a putative Ufm1 target that has been implicated in several signaling pathways but little is known regarding its in vivo function. In this report, by using multiple knockout mouse models, we demonstrate that UFBP1 is essential for murine development and blood cell development. While germ-line deletion of UFBP1 caused defective red blood cell development and embryonic lethality, somatic ablation of UFBP1 impaired production of mature red blood cells and other types of hematopoietic cells. We found that depletion of UFBP1 led to elevated stress in the endoplasmic reticulum that in turn caused cell death of hematopoietic stem cells. Furthermore, UFBP1 deficiency diminished expression of key transcription factors essential for red blood cell development. Taken together, our study provides strong genetic evidence for the essential role of UFBP1 as well as other components of the Ufm1 system in hematopoietic development. Therefore, the ufmylation pathway may represent a novel therapeutic target in treatment of blood diseases.

Introduction

The Ufm1 (Ubiquitin-fold modifier 1) conjugation system is a novel ubiquitin-like (Ubl) modification system that mediates protein modification by a small protein modifier Ufm1 [1]. Ufmylation is catalyzed by a series of enzymes, consisting of Ufm1-activating E1 enzyme (Uba5), Ufm1-conjugating E2 enzyme (Ufc1), and a newly identified E3 ligase Ufl1 [1–3]. The genetic study using Uba5 knockout mice demonstrates that Uba5 is essential for embryogenesis and erythroid development, highlighting the importance of this system in animal development [4]. Yet, its downstream effector(s) and molecular mechanism remain poorly understood.

UFBP1 (Ufm1 binding protein 1 with a PCI domain, also known as C20orf116, Dashurin, and DDRGK1) is a highly conserved protein whose orthologues are found in metazoan and plants but not in yeast, indicating its important role in multicellular organisms [2, 5–7]. It is ubiquitously expressed in multiple tissues and organs with high - level expression in secretory cells [7]. Human UFBP1 contains 314 amino acid residues with a putative signal peptide at its N-terminus that anchors it to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [2, 6]. It also contains a partial PCI domain that is frequently found in the subunits of the proteasome, COP9 signalosome and translation initiation factors. UFBP1 is found to associate with two other proteins namely C53 (also designated as LZAP, Cdk5rap3) and Ufl1 (also known as KIAA0776, NLBP, RCAD and Maxer) [2, 6]. Interestingly, Tatsumi et al found that UFBP1 was a Ufm1 target and its ufmylation at the highly conserved residue Lys267 was promoted by the Ufm1 E3 ligase Ufl1 [2]. Moreover, Yoo et al have recently demonstrated that the ufmylated form of UFBP1 is a co-component of Ufl1 E3 ligase that promotes ufmylation of nuclear receptor co-activator ASC1, an event that is crucial for estrogen receptor signaling and breast cancer development [8]. Nonetheless, little is known concerning the in vivo function of UFBP1 and the functional impact of its ufmylation.

In this study, we report the essential role of UFBP1 in murine development and hematopoiesis. Ablation of UFBP1 leads to impaired embryogenesis and defective hematopoiesis. Our results strongly suggest that UFBP1 functions as a key player in the ufmylation pathway that is crucial for cellular homeostasis and erythroid development.

Results

UFBP1 is essential for embryonic development

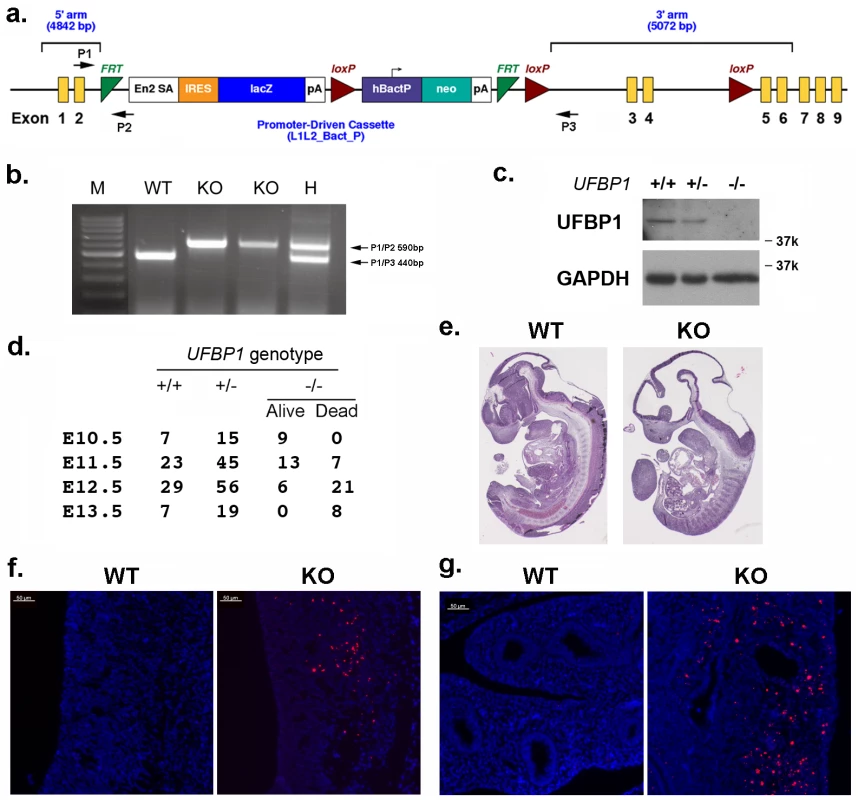

In an attempt to understand UFBP1’s in vivo function, we generated UFBP1 knockout mice. The murine UFBP1 gene is located in chromosome 2 and consists of 9 exons (Fig 1A). A gene trap cassette flanked by two FRT sites was inserted into the intron between exon 2 and 3 and followed by floxed exons 3 and 4, thereby creating a UFBP1Trap-F allele (Fig 1A). Insertion of the gene trap was confirmed by genomic PCR (Fig 1B). Disruption of UFBP1 expression was confirmed by the complete absence of UFBP1 protein in the embryos with homozygous trapped alleles (Fig 1C). Therefore, the mice with homozygous trapped alleles (UFBP1Trap-F/Trap-F) were designated as UFBP1-/- or UFBP1 KO mice.

Fig. 1. UFBP1 is essential for embryonic development.

a. The targeting vector of UFBP1 allele. b. PCR-based genotyping of UFBP1 allele with the gene trap cassette. c. Immunoblotting of UFBP1 protein in wild-type (WT) and KO embryos. d. Embryonic lethality of UFBP1 null embryos. e. Hematoxylin & eosin (H & E) staining of representative WT and KO embryos (E11.5). f. TUNEL staining of the bottom of the fourth ventricle of embryonic brain in E11.5 embryos. g. TUNEL staining of lumen of duodenum in E11.5 embryos. Scale bar: 50 μm. Among 158 adult mice, we failed to obtain UFBP1-/- animals while 51 UFBP1+/+ and 107 UFBP1+/- mice were born healthy and appeared normal, indicating a possible embryonic lethality caused by loss of UFBP1. By analyzing the embryos of timed-pregnant mice, we found that most UFBP1-/- embryos died at E12.5 (Fig 1D), a phenotype which is similar to the ones of Uba5 and Ufl1 KO mice but slightly delayed compared to Ufl1 KO mice [9]. E11.5 UFBP1-/- embryos appeared smaller and paler than their wild-type littermates (Fig 1E and S1 Fig). Extensive cell death (TUNEL staining) was observed in brain, liver and other tissues (Figs 1F, 1G and 2B). Taken together, our results suggest that UFBP1 is essential for proper embryogenesis and its deficiency leads to elevated cell death.

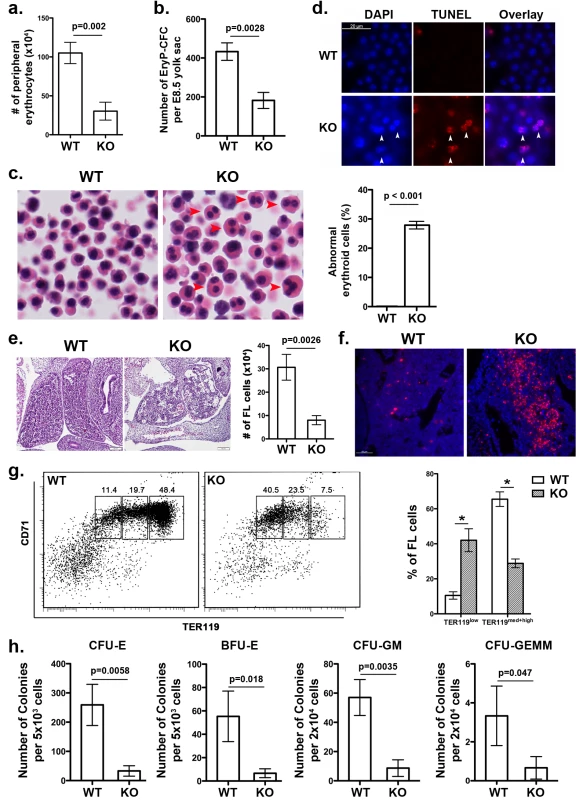

Fig. 2. UFBP1 deficiency impairs embryonic erythroid development.

a. The number of erythrocytes in peripheral blood of WT and KO E11.5 embryos. Blood cells were collected from suspension solution during separation of yolk sac from embryos and manually counted. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). b. The number of EryP-CFC in E8.5 yolk sac. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). c. Abnormal multi-nucleated erythroid cells in E11.5 embryos. Multi-nucleated erythrocytes are marked by red arrowheads in H & E stained sections. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). d. Representative photographs of TUNEL staining of circulating erythrocytes in E11.5 embryos. e. H & E staining and number of fetal liver cells in E11.5 embryos. The number of fetal liver cells was scored by counting total cells from dissected fetal livers. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). f. Representative photographs of TUNEL staining of fetal liver sections (E11.5). g. Representative flow cytometry analysis of fetal liver cells from E11.5 embryos. Fetal liver cells were freshly isolated from E11.5 embryos and subjected to flow cytometry analysis of CD71 and TER119 markers. Percentages of each population of cells are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). h. CFU-Es, BFU-Es, CFU-GMs, and CFU-GEMMs in E11.5 fetal livers. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). UFBP1 deficiency impairs embryonic erythropoiesis

Ablation of either Uba5 or Ufl1 leads to defective embryonic erythropoiesis [4, 9]. Therefore, it is of great interest to determine if UFBP1 deficiency also impacts on embryonic erythroid development. At E11.5, UFBP1 KO embryos had fewer peripheral circulating erythrocytes compared to wild-type embryos (Fig 2A), while UFBP1 deficient yolk sac (E8.5) contained a reduced number of primitive erythroid colony-forming cells (EryP-CFC) (Fig 2B). Additionally, there were a large number of abnormal multinucleated erythroid cells in UFBP1-/- embryos, a phenotype reminiscent of Uba5 and Ufl1 null embryos (Fig 2C) [4, 9]. Some multi-nucleated erythroid cells were TUNEL-positive, indicating occurrence of cell death of these cells (Fig 2D). These results indicate an impairment of primitive erythropoiesis in UFBP1 deficient embryos. We also examined definitive erythropoiesis in fetal livers. UFBP1 KO embryos (E11.5) had small and dis-organized fetal livers with less cellularity (Fig 2E) and increased cell death (Fig 2F). Flow cytometry analysis of E11.5 fetal liver cells showed that UFBP1 deficiency significantly blocked differentiation of TER119low cells into TER119med+high cells (proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts) cells (Fig 2G). Furthermore, the numbers of erythroid and myeloid progenitor cells, including CFU-Es (colony-forming units-erythrocytes), BFU-Es (erythroid burst-forming units), CFU-GM (colony-forming units - granulocyte/macrophage) and CFU-GEMM (colony-forming units - granulocyte/erythrocyte/macrophage/megakaryocyte), were significantly lower in UFBP1-/- fetal livers (E11.5) (Fig 2H). Taken together, our results suggest that UFBP1 plays an indispensable role in both primitive and definitive erythropoiesis during embryonic development.

Ablation of UFBP1 causes severe pancytopenia in adult mice

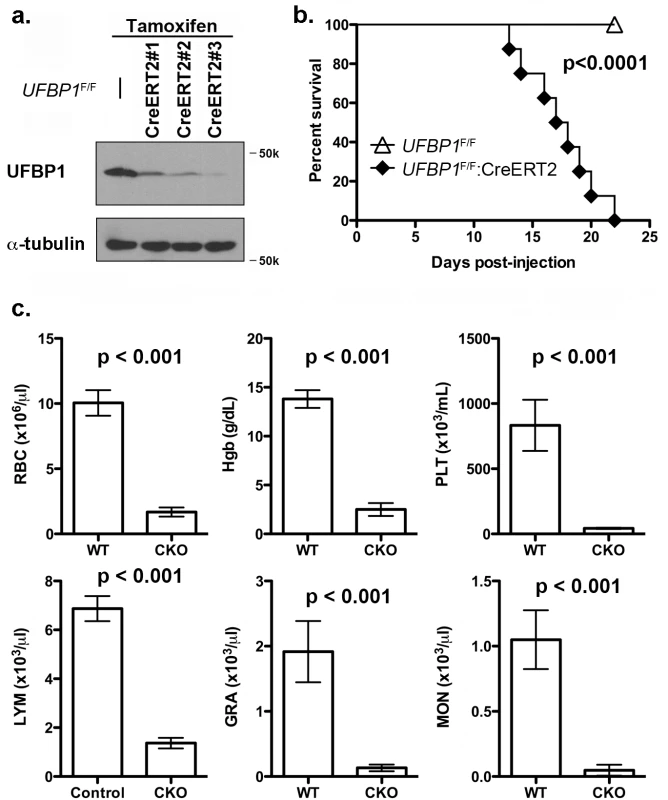

To investigate the in vivo role of UFBP1 in adult erythropoiesis, we generated inducible conditional KO (CKO) mice of UFBP1 via a two-step procedure: 1) removing the gene trap cassette by crossing UFBP1Trap-F/+ mice with FLPo deleter mice; and 2) crossing UFBP1 floxed mice with ROSA26-CreERT2 mice. As shown in Fig 3A, endogenous UFBP1 in bone marrow (BM) cells was depleted in tamoxifen (TAM)-treated UFBP1F/F:ROSA26-CreERT2 mice (designated as UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 hereafter) but not in UFBP1F/F mice (Fig 3A). Interestingly, UFBP1-depleted mice suffered substantial loss of body weight and died around 3 weeks after initial TAM treatment, while RCADF/F mice were fairly normal (Fig 3B). In the hematopoietic system, UFBP1 deficient mice exhibited severe pancytopenia (Fig 3C). The major indices for erythrocytes, including RBC (red blood cell) count and Hgb (hemoglobin) content, were significantly lower in UFBP1 deficient mice. Moreover, the counts for lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, as well as platelet counts were also dramatically decreased in UFBP1 deficient mice (Fig 3C). This result strongly indicates an essential role of UFBP1 in adult hematopoiesis.

Fig. 3. Loss of UFBP1 in adult mice results in severe pancytopenia and animal death.

a. Confirmation of UFBP1 depletion in bone marrow cells of TAM-injected CKO mice. Floxed mice were IP injected with tamoxifen according to a standard protocol. BM cells were collected and subject to immunoblotting of UFBP1. b. Survival curve of UFBP1 deficient mice after TAM injection, p < 0.001 (n = 12 each group). c. The result of CBC counts. Data are presented as means ± SD. The blood was drawn from control (UFBP1F/F) (n = 5) and UFBP1 deficient mice (UFBP1F/F:CreERT2) (n = 5) when UFBP1 deficient mice became moribund and/or lost 20% of body weight after TAM injection (between 2–3 weeks post-TAM treatment). Blood samples were subjected to CBC analysis. The mice used in this experiment were ~ 8-week old male mice. RBC: red blood cell; Hgb: hemoglobin; PLT: platelet; LYM: lymphocyte; GRA: granulocyte; MON: monocyte. Loss of UFBP1 impairs erythroid development at multiple stages

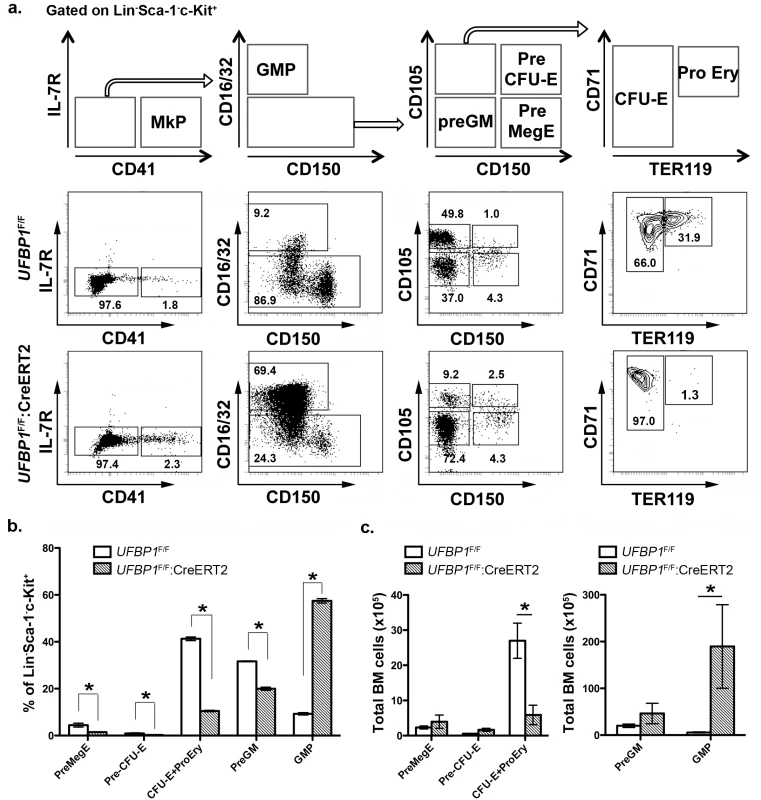

To further define the role of UFBP1 in adult erythropoiesis, we analyzed erythroid development in TAM-treated UFBP1 CKO mice according to Pronk et al [10]. The myeloerythroid (Lin-Sca-1-c-kit+IL-7R-) fraction of BM cells was subject to flow cytometry analysis using indicated markers (Fig 4A). As shown in Fig 4A, significant changes in myeloid and erythroid lineages were observed in UFBP1 deficient BM cells. The percentages of all types of erythroid progenitors, including Pre MegE (4.40 ± 0.81% vs 1.42 ± 0.16%), Pre CFU-E (0.89 ± 0.22% vs 0.25 ± 0.07%), and CFU-E plus proerythroblasts (41.23 ± 0.78% vs 10.43 ± 0.32%), were significantly decreased in TAM-treated UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 mice compared to UFBP1F/F mice (Fig 4A and 4B). Moreover, differentiation from CFU-Es (TER119low) to proerythroblasts (TER119high) was almost completely blocked by loss of UFBP1 (Fig 4A, the last panel). By contrast, the percentage of GMPs (9.24 ± 0.51% vs 57.40 ± 0.95%) was substantially increased in UFBP1 deficient BM, while the percentage of Pre GMs (31.60 ± 0.17% vs 19.9 ± 0.64%) was modestly decreased (Fig 4A and 4B). The total cell number of erythroid progenitors (CFU-Es + proerythroblasts) was also reduced in UFBP1 deficient BM, suggesting that UFBP1 plays a crucial role in development of erythroid lineage. Interestingly, although the number of GMPs in the UFBP1-deleted BM was dramatically expanded (Fig 4C), the number of mature monocytes/granulocytes in peripheral blood was decreased (Fig 3C), indicating that UFBP1 may also have a role in development of myeloid lineages.

Fig. 4. UFBP1 deficiency impairs lineage development of erythroid progenitors.

a. Flow cytometry analysis of erythroid and myeloid lineages in control and UFBP1 deficient mice after TAM injection. BM cells were collected from TAM-injected control (n = 4) and floxed (n = 4) male mice when UFBP1 deficient mice exhibited significant weight loss and became moribund. The following markers were used for flow analysis: BV510-Sca-1, APC780-c-Kit, PE-Cy7-CD150, Alexa 700-CD16/32, PE-IL-7R, APC-CD41, BV650-CD105, FITC-CD71, BV421-TER119, and lineage markers including PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated CD4, CD8, CD3, CD5, Gr-1, CD11b, CD19 and B220. b. The percentages of each lineage in L-S-K+ cells. *p <0.01, and **p <0.05 (n = 4). MkP: megakaryocyte progenitor; GMP: granulocyte macrophage progenitor; Pre GM: granulocyte macrophage precursor; Pre MegE: megakaryocyte erythroid precursor; Pre CFU-E: CFU-E precursor; CFU-E: erythroid colony-forming unit; Pro Ery: proerythroblast. c. The absolute cell numbers of each lineage in control and UFBP1-depleted BMs. UFBP1 depletion led to reduction of total BM cells (1 x 108 cells in control versus 5 x 107 in UFBP1 deficient mice). *p <0.01 (n = 4). UFBP1 deficiency impairs hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function in a cell-autonomous manner

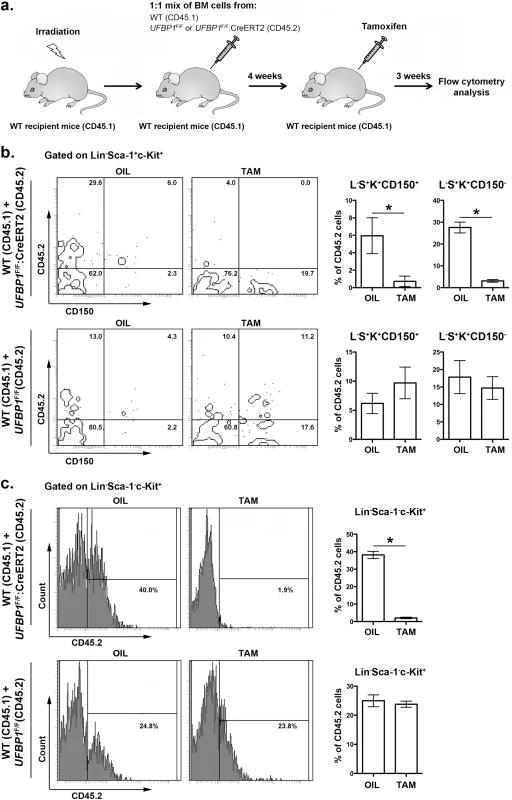

In addition to impaired erythropoiesis, UFBP1 deficient mice also exhibited cytopenia of other types of hematopoietic cells (Fig 3C), indicating a possible loss of HSC function. In line with this hypothesis, UFBP1 deficient BMs failed to rescue lethally irradiated recipient mice (S2 Fig). To further assess the cell intrinsic role of UFBP1 in HSC function, we performed competitive repopulation assays. Unfractionated BM cells from either UFBP1F/F or UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 (CD45.2) were mixed with wild-type (CD45.1) BM cells at a 1 : 1 ratio, and co-transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient CD45.1 mice (Fig 5A). Four weeks after transplantation, mice were treated with either oil or tamoxifen. Three weeks after initiation of the treatment, we examined the contribution of donor cells (CD45.2) to HSCs and other progenitor cells in BM. As shown in S3 Fig, the contribution of UFBP1 deficient (UFBP1F/F:CreERT2) cells to Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) population was substantially diminished after TAM treatment comparing to oil treatment (32.78 ± 1.79% vs 3.35 ± 0.28%). By contrast, TAM treatment yielded no effect on the contribution of UFBP1F/F cells (S3 Fig). Further analysis using CD150 marker showed that the contribution of UFBP1 deficient cells to both long-term HSCs (L-S+K+CD150+) (5.95 ± 1.02% vs 0.73 + 0.30%) and multipotent progenitors (L-S+K+CD150-) (27.58 ± 1.24% vs 3.13 ± 0.31%) was significantly reduced (Fig 5B). Similarly, oligopotent progenitors (L-S-K+) (38.18 ± 1.08% vs 2.08 ± 0.21%) contained much lower level of UFBP1 deficient cells (Fig 5B). The result of competitive repopulation assays strongly suggests that UFBP1 is essential for HSC function in a cell-autonomous manner.

Fig. 5. UFBP1 is essential for HSC function.

a. Experimental scheme for competitive repopulation assay. b. Contribution of UFBP1 deficient cells (CD45.2) to long-term HSCs (L-S+K+CD150+) and multipotent progenitors (L-S+K+CD150-). * p < 0.001 (n = 5). c. Contribution of UFBP1 deficient cells (CD45.2) to oligopotent progenitor cells (L-S-K+). * p < 0.001 (n = 5). Data are presented as means ± SD. The unfractionated BM cells from either UFBP1F/F or UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 (CD45.2) were mixed with wild-type (CD45.1) BM cells at a 1:1 ratio, and co-transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient CD45.1 mice. Four weeks after transplantation, the mice were treated with either oil or TAM. Three weeks after initiation of the treatment, the BM cells were isolated and subjected to flow analysis using indicated markers. UFBP1 depletion activates the UPR and cell death program in LSK cells

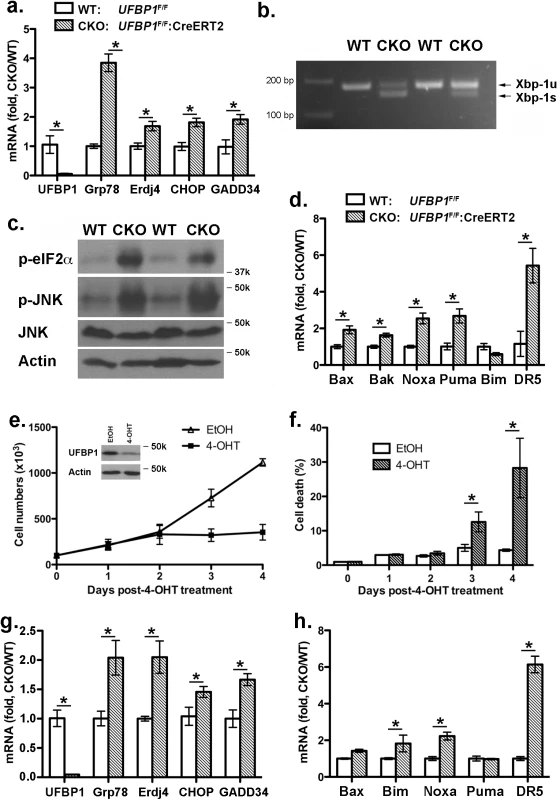

UFBP1 and other components of the Ufm1 system play a cytoprotective role in ER stress-induced apoptosis [7, 11]. Therefore, we examined the effect of UFBP1 deficiency on ER homeostasis. Expression of ER chaperones Grp78 and ERdj4 was up-regulated in UFBP1 deficient BM cells (Fig 6A), and UFBP1 depletion induced Xbp-1 mRNA splicing (Fig 6B) and elevation of phosphorylation of eIF2α and JNK (Fig 6C). These results indicate that UFBP1 deficiency indeed led to elevated ER stress and activation of the UPR. Furthermore, a subset of apoptotic genes associated with ER stress, including Bax, Bak, Noxa, Puma and DR5, were up-regulated in UFBP1 deficient cells (Fig 6D). In contrast to UFL1 deficient cells, however, we did not observe apparent inhibition of autophagic flux in UFBP1 deficient BM cells (S4 Fig). We also examined the effect of UFBP1 depletion on LSK cells in vitro. Sorted UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 LSK cells were treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) and cultured for indicated time. 4-OHT-induced depletion of UFBP1 led to a significant decrease of proliferation and increase of cell death of LSK cells (Fig 6E and 6F). Consistent with the in vivo result, the UPR and cell death genes were up-regulated in UFBP1-depleted LSK cells (Fig 6G and 6H). Collectively, our results suggest that UFBP1 plays an essential role in survival of LSK progenitor cells by maintaining ER homeostasis.

Fig. 6. Loss of UFBP1 activates the UPR and cell death program.

a. Up-regulation of Grp78, ERdj4 and CHOP in UFBP1 deficient BM cells. Total RNAs were purified from BM cells and subject to quantitative RT-PCR analysis (normalized to β-actin gene). TAM-injected UFBP1F/Fmice were used as WT control mice, while TAM-injected UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 mice were designated as CKO mice. The ratio of CKO to WT was presented. * p < 0.01 (n = 3). Data are presented as means ± SD. b. Xbp-1 mRNA splicing in UFBP1 deficient BM cells. Total RNAs were isolated from BM cells of control and CKO mice, and subjected to Xbp-1 mRNA splicing assay. c. Elevation of phosphorylation of eIF2α and JNK in UFBP1 deficient cells. Total cell lysates of BM cells were subjected to immunoblotting of indicated antibodies. d. Up-regulation of cell death genes in UFBP1 deficient BM cells. Total RNAs were purified from BM cells and subject to quantitative RT-PCR analysis (normalized to β-actin gene). The ratio of CKO to WT was presented. * p < 0.01 (n = 3). e. Proliferation of wild-type and UFBP1 deficient LSK cells. LSK cells were sorted from BM of UFBP1F/F:CreERT2 mice, and cultured in the absence or presence of 4-OHT (1 μM) for indicated period of time. Cell numbers were manually scored. The experiment was performed three times independently. f. Cell death of UFBP1 deficient HLSK cells. Cell death was elevated by DNA dye exclusion assay. g. Up-regulation of UPR genes in UFBP1 deficient LSK cells. Total RNAs were purified from LSK cells and subject to quantitative RT-PCR analysis (normalized to β-actin gene). The ratio of CKO to WT was presented. * p < 0.01 (n = 3). h. Up-regulation of cell death genes in UFBP1 deficient LSK cells. The ratio of CKO to WT was presented (normalized to β-actin gene). * p < 0.01 (n = 3). Loss of ufmylation capacity leads to elevated ER stress and suppression of erythroid transcriptional program

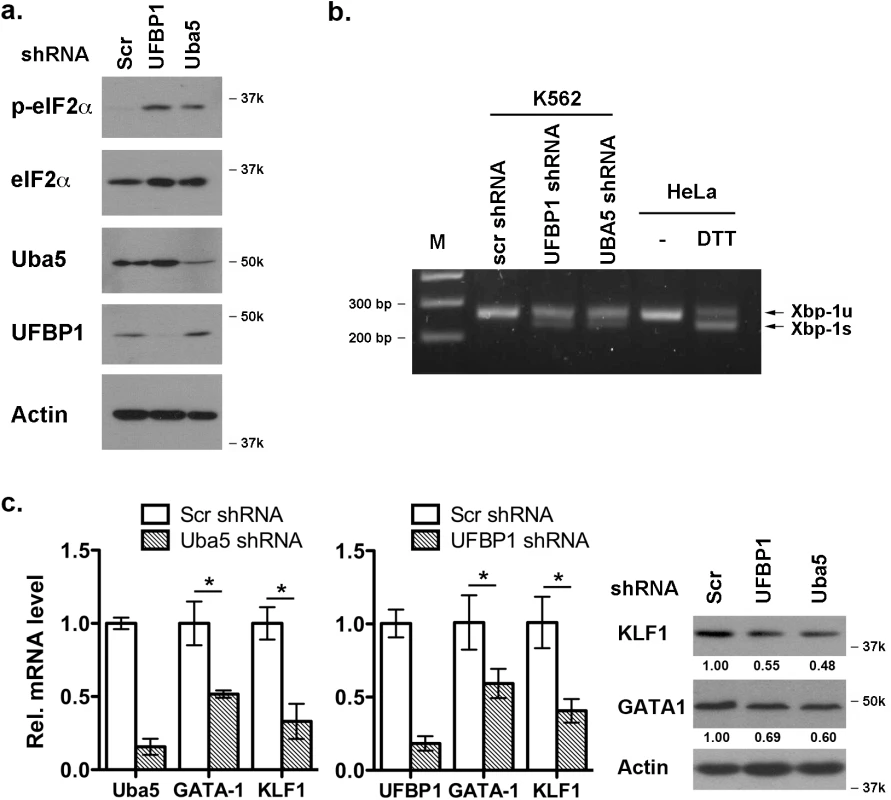

It has been shown that Uba5 is essential for embryonic erythropoiesis, but the underlying mechanism remains poorly understood [4]. We examined whether Uba5 exerts its function in similar cellular pathways in which UFBP1 is involved. As shown in Fig 7A and 7B, knockdown of either Uba5 or UFBP1 in erythroleukemia K562 cells caused the increase of eIF2α phosphorylation and Xbp-1 mRNA processing, indicating activation of the UPR in these knockdown cells. This result suggests that Uba5 is also involved in regulation of ER homeostasis. Furthermore, depletion of either Uba5 or UFBP1 down-regulated key erythroid transcription factors GATA-1 and KLF1 in K562 cells (Fig 7C), suggesting a lineage-specific role of ufmylation in erythropoiesis. Together, our results provide the first evidence suggesting that the Ufm1 system as a whole have pleiotropic roles in multiple cellular processes including maintenance of ER homeostasis and transcriptional regulation of erythroid development.

Fig. 7. Depletion of Uba5 activates the UPR and suppresses expression of erythroid transcription factors in K562 cells.

a. Elevation of phosphorylation of eIF2α in Uba5- and UFBP1-depleted K562 cells. b. Xbp-1 mRNA splicing in Uba5- and UFBP1-depleted K562 cells. mRNA from DTT (dithiothreitol)-treated HeLa cells was used as a positive control. c. Under-expression of GATA-1 and Klf1 in Uba5- and UFBP1-depleted K562 cells. Total RNAs were purified from K562 cells and subject to quantitative RT-PCR analysis (normalized to β-actin gene). The data are presented as the relative level to the K562 cells treated with scrambled shRNA. * p < 0.01 (n = 3). Total cell lysates were subject to immunoblotting of indicated antibodies. Depletion of ASC1, a Ufm1 target, down-regulates the erythroid transcriptional program but does not elevate ER stress

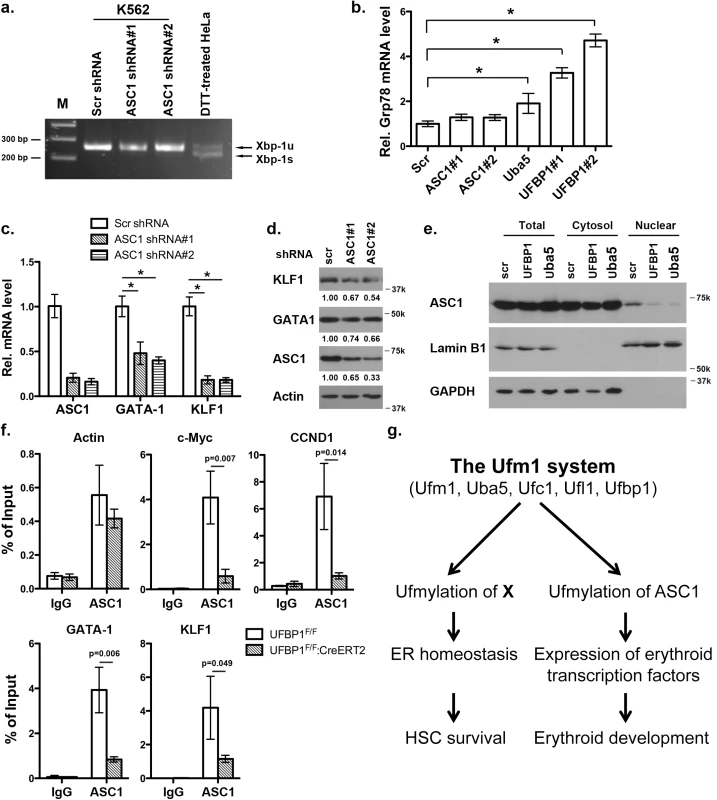

ASC1, a co-activator of hormone receptors, is a newly identified Ufm1 target [8]. Its ufmylation promotes recruitment of other transcription factors and thereby enhances estrogen receptor-mediated transcription [8]. Interestingly, in contrast to Uba5 and UFBP1, depletion of ASC1 in K562 cells did not promote Xbp-1 mRNA splicing and Grp78 up-regulation, indicating that ASC1 knockdown does not cause elevation of basal ER stress (Fig 8A and 8B). However, ASC1 knockdown led to significant under-expression of GATA-1 and KLF1, suggesting a crucial role of ASC1 in regulation of erythroid transcription program (Fig 8C and 8D). We further examined the effect of UFBP1 and Uba5 knockdown on ASC1. Knockdown of either UFBP1 or Uba5 in K562 cells did not change ASC1 protein level (Fig 8E), but caused the reduction of its nuclear presence (Fig 8E). Given that ASC1 functions as a transcription co-activator, we speculated a direct role of ASC1 in transcriptional regulation of erythroid genes such as Gata-1 and Klf1. To test this possibility, we performed chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using UFBP1-depleted BM and spleen cells to examine whether ASC1 is associated with Gata-1 and Klf1 promoters. Depletion of UFBP1 did not alter ASC1 expression in UFBP1 deficient bone marrow cells (S5A Fig). Both c-Myc and CCND1 (cyclin D1) were reported to be ASC1 targets in breast cancer cells [8]. In agreement with the previous report, ASC1 was indeed associated with the promoters of c-Myc and CCND1, and more importantly, the associations were significantly decreased in UFBP1 deficient BM cells (Fig 8F). As a negative control, the beta-actin promoter sequence was slightly enriched in ASC1-DNA complex but the enrichment was not affected by UFBP1 depletion (Fig 8F). Intriguingly, both Gata-1 and Klf1 promoter sequences were substantially enriched in ASC1-DNA complex, and the enrichment was significantly diminished by UFBP1 deficiency (Fig 8F). Similar result was obtained using UFBP1 deficient spleen cells (S5B Fig). Together, our results strongly suggest that ASC1 is one of the key downstream effectors of the Ufm1 system to transcriptionally regulate erythroid lineage development.

Fig. 8. Knockdown of ASC1 down-regulates expression of erythroid transcription factors but does not activate the UPR.

a. Xbp-1 mRNA splicing in ASC1-depleted K562 cells. mRNA from DTT (dithiothreitol)-treated HeLa cells was used as a positive control. b. Expression of Grp78 in K562 cells with knockdown of ASC1, Uba5 and UFBP1. The data are presented as the relative level to K562 cells treated with scrambled shRNA. * p < 0.01 (n = 3). c. Expression of GATA-1 and Klf1 in ASC1-knockdown K562 cells. The data are presented as the relative level to the cells with scrambled shRNA. * p < 0.01 (n = 3). d. GATA-1 and KLF1 protein level in ASC1 knockdown cells. e. Subcellular localization of ASC1 in UFBP1 and Uba5 knockdown K562 cells. Subcellular fractionation of K562 cells was performed according to [6]. Lamin B1 was used as the nuclear marker, while GAPDH was used as the cytosolic marker. f. ChIP analysis of ASC1 association to the promoters of GATA-1 and Klf1 genes in BM cells. BM and spleen cells were isolated from phenylhydrazine-treated control and UFBP1 CKO mice, and subjected to ChIP assays. c-Myc and CCND1 promoters were used as positive ASC1 targets while actin promoter was the negative control. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). g. A working model for the role of ufmylation in regulation of hematopoiesis. Discussion

In this study, we report that UFBP1, a key component of the Ufm1 conjugation system, is essential for murine erythropoiesis in both embryonic and adult stages. Germ-line inactivation of UFBP1 caused anemia and embryonic lethality around E12.5 (Figs 1 and 2), whereas induced ablation of UFBP1 in adult mice impaired hematopoiesis, resulting in severe pancytopenia and animal death (Figs 3 and 4). We found that defective hematopoiesis in UFBP1 deficient mice was in part caused by sustained ER stress-induced cell death of HSCs (Figs 5 and 6). Furthermore, ablation of ufmylation capacity, including depletion of Uba5 (E1), UFBP1 (E3 co-activator) or ASC1 (Ufm1 target), significantly down-regulated expression of erythroid transcription factors (Figs 7 and 8). Interestingly, depletion of Ufm1 target ASC1 caused under-expression of GATA-1 and Klf1, but not elevation of ER stress (Fig 7). Taken together, our findings strongly suggest that the Ufm1 system plays crucial pleiotropic roles in regulating both cell survival and differentiation during hematopoiesis. Accordingly, we propose a working model for ufmylation-mediated regulation of hematopoiesis: its activity in maintaining ER homeostasis is essential for survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, whereas ufmylation of ASC1 is crucial for high-level expression of erythroid transcription factors and erythroid lineage development (Fig 8G)

Previous studies have shown that UFBP1 is a putative Ufm1 target, and its ufmylation is promoted by Ufm1 E3 ligase Ufl1 [2]. Furthermore, Ufm1-modified UFBP1 is required for ufmylation of another Ufm1 target ASC1 [8], indicating that UFBP1 may function as a co-factor of Ufm1 E3 ligase. Interestingly, we found that UFBP1 KO mice shared extensive phenotypic similarities with Ufl1 and Uba5 KO mice in hematopoietic system. First, ablation of either gene impaired embryonic erythropoiesis and caused embryonic lethality around E10.5-E12.5, even though death of UFBP1 null embryos appeared to occur slightly delayed compared to Ufl1 null embryos [4, 9]. This delayed death of UFBP1 null embryos may be attributed to the fact that Ufl1 also regulates C53 protein that is essential for embryogenesis (Fig 1 and [6, 12, 13]). Second, a high number of multi-nucleated erythrocytes were found is all KO embryos (Fig 2 and [4, 9]). Third, UFBP1 and Ufl1 KO mice exhibited nearly identical defects in erythroid development (Fig 4 and [9]). Together, these phenotypic similarities strongly suggest that UFBP1 is indeed a key downstream effector of the Ufm1 system in ufmylation-mediated regulation of hematopoietic development. Interestingly, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) study has identified one SNP (rs11697186) in DDRGK1 (same as UFBP1) gene that is strongly associated with anemia and thrombocytopenia in peggylated interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C patients, which provides clinical evidence for possible involvement of UFBP1 in regulation of erythropoiesis [14]. Nevertheless, it is also worth noting that UFBP1 deficient mice do have a subtle phenotypic difference compared to Ufl1 KO mice. Autophagic flux appeared to be normal in UFBP1 deficient cells (S4 Fig), whereas Ufl1 deficiency caused inhibition of autophagic degradation [9]. It has been shown that Ufl1 knockdown results in significant depletion of both C53 and UFBP1 proteins [6, 12]. Our result indicates that depletion of UFBP1 protein may not be the causative factor for blockage of autophagic flux in Ufl1 deficient cells.

Similar to Ufl1 deficient cells, UFBP1-depeted LSK cells displayed elevated ER stress that in turn caused activation of the UPR and cell death program (Fig 6). ER homeostasis is crucial for survival and function of HSC and other progenitor cells [15]. The UPR is a highly coordinated program that facilitates protein folding, processing, export and degradation of proteins during cellular response to ER stress. It generally includes three signaling branches: IRE1 (Inositol requiring enzyme 1), PERK (PKR-like ER kinase) and ATF6 [16]. Although the UPR serves as a cytoprotective role to restore ER homeostasis, persistent activation of IRE1 and PERK signaling caused by unresolved ER stress also leads to cell death and tissue damage [16]. It has been reported that HSCs and other progenitor cells exhibit distinct cellular response to extracellular ER stressors, and the PERK-eIF2α-CHOP pathway predisposes human HSCs to ER stress-induced apoptosis [15]. Furthermore, overexpression of ER chaperone ERdj4 and RNA-binding protein Dppa5/Esg1 in HSCs reduced ER stress and thereby improved HSC survival and stemness function [15, 17]. Interestingly, we found that depletion of either UFBP1 or Uba5 led to elevated ER stress and activation of the UPR, and sustained ER stress may contribute to cell death of HSCs (Figs 6 and 7). This result is line with the previous studies showing that the Ufm1 system protects pancreatic beta cells and macrophages from ER stress-induced apoptosis [7, 11]. Our finding suggests that the Ufm1 system plays a cytoprotective role by maintaining ER homeostasis of HSCs. Therefore, manipulation of ufmylation activity may represent a novel approach to improve survival and function of HSCs.

In addition to their role in maintaining ER homeostasis that appears to be a general function in most types of cells we examined, UFBP1 and Ufl1 also possess a lineage-specific activity, which was evidenced by the complete blockage of differentiation of CFU-Es to proerythroblasts in both UFBP1 and Ufl1 deficient bone morrows (Fig 4A and [9]). This lineage-specific effect was also observed in Uba5 deficient embryos, in which development of MEP (megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors), but not GMPs (granulocyte macrophage progenitors), was impaired in fetal livers [4]. Yet, the molecular basis of this erythroid-specific activity remains largely unknown. In this study, we found that ASC1, a transcription co-activator and Ufm1 target, was the key downstream effector to mediate this lineage-specific activity. ASC1 was originally identified as thyroid hormone receptor interactor 4 (TRIP4) [18, 19]. As a transcriptional co-activator, ASC1 enhances transcription by recruiting nuclear receptors (such as ERα), transcriptional cofactors (p300 and SRC1), and basic transcriptional machinery (TBP and TFIIA) to specific promoters, and its ufmylation provides a platform for the recruitment of these factors [8]. Interestingly, it has been known that nuclear receptor signaling pathways play a crucial role in both normal and stress erythropoiesis. Altering the content of thyroid hormone receptor α (TRα) in chicken erythroblasts affects the balance between proliferation and differentiation [20]. TRα-/- mice display defective fetal and adult erythropoiesis and an altered stress erythropoiesis response to hemolytic anemia [21, 22]. Moreover, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) signaling is important for stress erythropoiesis [23], while retinoic acid (RA) has a broad impact on hematopoiesis [24]. Estrogen receptor was also reported to modulate HSC survival and erythropoiesis [25]. Therefore, it is quite plausible that ASC1 and its ufmylation may be directly involved in regulation of erythroid development. To support our hypothesis, we found that knockdown of ASC1 in K562 down-regulated key erythroid transcription factors GATA-1 and KLF1 (Fig 8C). More importantly, ChIP analysis showed that ASC1 was associated with the promoters of GATA-1 and Klf1, and this association was significantly attenuated by depletion of UFBP1 (Fig 8E), suggesting that ufmylation of ASC1 is important for its association with the promoters of GATA-1 and Klf1. Further studies are needed to identify and characterize both extracellular and intracellular signals leading to ASC1 ufmylation and its binding partners, and to determine the molecular mechanism of ASC1-mediated regulation of erythroid development. In addition, our results also indicate an important role of UFBP1 in development of other lineages such as myeloid cells. Tissue - and lineage-specific genetic models will be generated for thorough elucidation of its function and working mechanism in the hematopoietic system.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Our animal study was conducted according to the guidelines of Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE). IACUC of Georgia Regents University approved this study (protocol #2011–0314)

Tissue culture cells and chemical reagents

K562 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Tamoxifen and 4-hydroxytamoxifen and other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Generation of UFBP1 KO and CKO mice and genotyping

ES cell clone HEPD0618_2_D02 (JM8A3.N1 with C57BL/6N background) containing trapped UFBP1 allele was purchased from the EUCOMM (European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis) team. The ES cells were injected into the blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice (Northwestern University Transgenic and Targeted Mutagenesis Laboratory). Chimeric mice were crossed with B6(Cg)-TyrC-2J/J albino mice, and heterozygous offspring with germ-line transmission were confirmed by genotyping.

To generate CKO mice, we crossed UFBP1Trap-F/+ mice with FLPo deleter mice (B6(C3)-Tg(Pgk1-FLPo)10Sykr/J, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar harbor, ME) to remove the gene trap cassette. The floxed UFBP1 mice were crossed with ROSA26-CreERT2 mice (B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sor<tm1(cre/ERT2) Tyj>/J, The Jackson Laboratory) in which CreERT2 was inserted into ROSA26 locus. Cre-mediated deletion of UFBP1 was induced by tamoxifen administration. Tamoxifen (20 mg/ml in corn oil, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was administrated by 5-day IP injection with an approximate dose of 75 mg tamoxifen/kg body weight. All animal procedures were approved by IACUC of Georgia Regents University.

The following primers were used for PCR genotyping of UFBP1 KO embryos and mice: P1 (TAGTACTTGAAGTCTGGCTTGGTA), P2 (CACAACGGGTTCTTCTGTTAGT CC) and P3: (TAGTCAGGAACTGATGA GTGTCTC). A 35-cycle (92°C, 45 sec, 62°C, 45 sec, 72°C 45 sec) PCR was performed in the present of 1% DMSO, and the determination of genotypes was described in Fig 1. For the floxed UFBP1 allele, P1 and P3 primers were used in PCR genotyping. The floxed allele generates a 637 bp PCR product comparing to 440 bp WT product. Genotyping of Cre-ERT2 mice was performed according to the standard protocol of the Jackson Laboratory.

Complete blood count and colony formation assays

Fetal liver cells (5,000 cells) were plated in one ml of serum-free methylcellulose and IMDM (M3234, Stem Cell Technology, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For CFU-Es, cells were cultured for 3 days in the presence of hEpo (2 units/ml, Epogen, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and stained with benzidine dihydrochloride, and the number of colonies is scored. For BFU-Es, cells were cultured in the presence of hEpo (2 units/ml) and mSCF (100 ng/ml, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 7 days, stained and scored. For CFU-GMs, CFU-GEMMs, BM or fetal liver cells (20,000) were cultured in M3434 (Stem Cell Technology) for 5 days, and the numbers of the colonies were manually counted. For EryP-CFCs, yolk sac cells from E8.5 embryos was cultured in IMDM medium containing 10% plasma-derived serum, 5% PFHM-II, 0.025 mg/ml ascorbic acid, 4.5 x 10−4 M MTG, Epo (2 U/ml), and colonies were manually counted after 96 hours.

Complete blood counts (CBC) of blood samples from adult mice were analyzed by in-house Horiba ABX Micro S60 analyzer (HORIBA Medical, Irvine, CA, USA).

Competitive repopulation assay

Recipient mice (CD45.1) were first irradiated with dose of 9 Gy. BM cells from UFBP1F/F and UFBP1F/F;ROSA-CreERT2 mice (CD45.2) were isolated, mixed with BM cells from CD45.1 mice in a 1 : 1 ratio (1x106 cells total), and subsequently injected into the retro-orbital venous sinus of anesthetized recipient mice (5 mice for each group). After a 4-week recovery period, tamoxifen was administered in 5 consecutive days. Donor cell engraftment was monitored by flow cytometry of the blood samples from tail veins in a 2-week interval using lineage markers. After 3 weeks of tamoxifen injection, BM cells were subjected to flow analysis.

In vitro culture of LSK progenitor cells

Sorted BM HSC and myeloerythroid progenitor cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, hEpo (2 units/ml, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), mSCF (100 ng/ml, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), mIL-3 (10 ng/ml, Peprotech), Dexamethasone (1 μM, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and IGF-1 (100 ng/ml, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Deletion of UFBP1 was induced by addition of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (1 μM, Sigma).

Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting

Freshly isolated BM cells were suspended in PBS with 1% fetal bovine serum and stained with BV510-Sca-1 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), APC780-c-Kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), PE-Cy7-CD150 (Biolegend), Alexa700-CD16/32 (eBioscience), PE-IL-7R (BD Biosciences), APC-CD41 (BD Biosciences), BV650-CD105 (Biolegend), FITC-CD71 (BD Biosciences), BV421-TER119 (Biolegend), and PerCP-Cy5.5 conjugated lineage markers including CD4, CD8, CD3, CD5, Gr-1, CD11b, CD19 and B220 (BD Biosciences). The samples were analyzed using BD LSR II SORP and Diva 7.0 software (GRU Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Facility). For competitive repopulation assays, BV421-CD45.2 (Biolegend) was used to substitute BV421-TER119. Cell sorting of HSCs and progenitor cells was performed using BD FACSAria II SORP.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from each sample was isolated with the GeneJET RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific), and then reversely transcribed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. RT-PCR was performed using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix kit (BIO-RAD) with 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute on StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). The results were analyzed by StepOne Software (Version 2.1, Life Technologies). Relative expression level of each transcript was normalized to murine beta-actin and GAPDH by using the 2^(-delta delta Ct) method. The following is the list of primers used in this study:

Genes Primer sequence

Mouse Actin GACCTCTATGCCAACACAGT

AGTACTTGCGCTCAGGAGGA

Mouse UFBP-1 GAAGCCAGCAGAAGTTCACC

GAAGCCGTTCCTCTTCCTTC

Mouse Grp78 ACTTGGGGACCACCTATTCCT

ATCGCCAATCAGACGCTCC

Mouse ERdj4 TAAAAGCCCTGATGCTGAAGC

TCCGACTATTGGCATCCGA

Mouse CHOP GCATGAAGGAGAAGGAGCAG

ATGGTGCTGGGTACACTTCC

Mouse GADD34 AGAACATCAAGCCACGGAAG

TCTCAGGTCCTCCTTCCTCA

Mouse Bax TGCAGAGGATGATTGCTGAC

AAGATGCTGTTGGGTTCCAG

Mouse Bak AAAATGGCATCTGGACAAGG

AAGATGCTGTTGGGTTCCAG

Mouse Bim TGCAGAGGATGATTGCTGAC

GATCAGCTCGGGCACTTTAG

Mouse Noxa GGCAGAGCTACCACCTGAGT

TTGAGCACACTCGTCCTTCA

Mouse Puma GCCCAGCAGCACTTAGAGTC

TGTCGATGCTGCTCTTCTTG

Mouse DR5 TGACTACACCAGCCATTCCA

AGTTCCTCTTCCCCGTCAGT

Human Actin CCTGTACGCCAACACAGTGC

ATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCC

Human Gata1 GATGGAATCCAGACGAGGAA

GCCCTGACAGTACCACAGGT

Human Klf1 CACGCACACGGGAGAGAAG

CGTCAGTTCGTCTGAGCGAG

Human UFBP-1 GAAGCCAGCAGAAGTTCACC

GAAGCCGTTCCTCTTCCTTC

Human Grp78 ACTTGGGGACCACCTATTCCT

ATCGCCAATCAGACGCTCC

Human ASC1 AGTGGGTTGACCACACAGGT

CTGCCCTCCACCCTTTTAAT

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

For ASC1 ChIP assay, UFBP1F/F (control) and UFBP1F/F;CreERT2 mice were injected with tamoxifen for 5 consecutive days. At day 4, mice were injected with a single dose of phenylhydrazine (40 mg/kg). Bone marrow and spleen cells were harvested at day 8, and subjected to ChIP and quantitative PCR analysis as previously described [26, 27]. The following primers were used for detection of specific promoters: mKLF1-chip, AGCGACCAGGACTTTTCTTT (F) and CGATATGTGTGT GGTGTGCT (R); mGATA1-chip, CCAACTCCTGCAAGAACA GT (F) and GTTGACACTA GCCCCACAGT (R). mActin-chip, TCTCCAAAAGTGCCTGACTC (F) and CCCTTCTGCTGTGGTTCTAA (R); mMyc-chip, CGACCAAAGGCAAAATACAC (F) and CCCTGCGTATATCAGTCACC (R); mCCND1-chip, CTCCCCCAACTCAAGACTG (F) and AATTCCAGCAACAGCTCAAG (R).

Xbp-1 mRNA splicing assay

Xbp-1 mRNA splicing assay was conducted as described previously [26], using the following primers: for human Xbp-1: 5’ GGAGTTAAGACAGCGC TTGG 3’ (F) and 5’ ACTGGGTCCAAGTTGTCCAG 3’ (R); and for murine Xbp-1, 5’ ACACGCTTG GGAAT GACAC 3’ (F) and 5’ CCATGGGAAGATGTTCTGGG 3’ (R).

shRNA constructs

Lentiviral vectors expressing specific shRNAs were constructed using pLKO.1 vector. Lentiviruses were prepared using 293FT packaging cell line according to the manufacturer's instruction (Invitrogen). The following shRNAs were used:

hUba5 shRNA: CCTCAGTGTGATGACAGAAAT;

hUFBP1 shRNA#1: GTGTCGAGAAGCCAGCGGAAA;

hUFBP1 shRNA#2: GGAGCTAAGAAACTGCGGAAG;

hASC1 shRNA#1: GCAGAGTATCATAGCAGACTA;

hASC1 shRNA#2: GGACTAGAGTTCAACTCATTT.

For knockdown assays, K562 cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing either scrambled or gene-specific shRNAs for 24 hours, and then selected with puromycin (1.5 μg/ml) and culture for 3 to 4 days. Knockdown efficiency was evaluated by either immunoblotting or quantitative RT-PCR.

Antibodies, immunoblotting and immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescent staining and Immunoblottings were performed as described previously6. Confocal images were acquired using Zeiss 510 META confocal microscope with Zen software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany), while epifluorescence images were obtained using Zeiss Observer D1 with AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany).

The antibodies used in this study include: UFBP1 and Uba5 rat antibody (Li lab and [6, 26]), eIF2α, phospho-S51-eIF2α (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), ASC1 (A300-843A, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA), JNK and phospho-JNK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), GATA-1 and KLF1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), α-tubulin and β-actin (Sigma). All affinity-purified and species-specific HRP - and fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA).

TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was performed using In situ cell death detection kit (Fluorescein, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Histology

For hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining of embryo sections, the embryos were fixed in 10% formalin overnight, rinsed with PBS and embedded in paraffin. Embryo sections were deparaffinized and hydrated, and subsequently stained with hematoxylin solution for 6 minutes. After rinse in water for 15 minutes, the sections were stained with eosin-Y solution for 3 minutes. The sections were then rinsed in water, dehydrated and mounted with Permount.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Komatsu M, Chiba T, Tatsumi K, Iemura S, Tanida I, Okazaki N, et al. A novel protein-conjugating system for Ufm1, a ubiquitin-fold modifier. The EMBO journal 2004, 23(9): 1977–1986. 15071506

2. Tatsumi K, Sou YS, Tada N, Nakamura E, Iemura S, Natsume T, et al. A novel type of E3 ligase for the Ufm1 conjugation system. The Journal of biological chemistry 2010, 285(8): 5417–5427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036814 20018847

3. Daniel J, Liebau E. The ufm1 cascade. Cells 2014, 3(2): 627–638. doi: 10.3390/cells3020627 24921187

4. Tatsumi K, Yamamoto-Mukai H, Shimizu R, Waguri S, Sou YS, Sakamoto A, et al. The Ufm1-activating enzyme Uba5 is indispensable for erythroid differentiation in mice. Nat Commun 2011, 2 : 181. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1182 21304510

5. Neziri D, Ilhan A, Maj M, Majdic O, Baumgartner-Parzer S, Cohen G, et al. Cloning and molecular characterization of Dashurin encoded by C20orf116, a PCI-domain containing protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1800(4): 430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.12.004 20036718

6. Wu J, Lei G, Mei M, Tang Y, Li H. A novel C53/LZAP-interacting protein regulates stability of C53/LZAP and DDRGK domain-containing Protein 1 (DDRGK1) and modulates NF-kappaB signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry 2010, 285(20): 15126–15136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110619 20228063

7. Lemaire K, Moura RF, Granvik M, Igoillo-Esteve M, Hohmeier HE, Hendrickx N, et al. Ubiquitin fold modifier 1 (UFM1) and its target UFBP1 protect pancreatic beta cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis. PLoS One 2011, 6(4): e18517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018517 21494687

8. Yoo HM, Kang SH, Kim JY, Lee JE, Seong MW, Lee SW, et al. Modification of ASC1 by UFM1 is crucial for ERalpha transactivation and breast cancer development. Molecular cell 2014, 56(2): 261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.007 25219498

9. Zhang M, Zhu X, Zhang Y, Cai Y, Chen J, Sivaprakasam S, et al. RCAD/Ufl1, a Ufm1 E3 ligase, is essential for hematopoietic stem cell function and murine hematopoiesis. Cell death and differentiation 2015 (Epub ahead of print).

10. Pronk CJ, Rossi DJ, Mansson R, Attema JL, Norddahl GL, Chan CK, et al. Elucidation of the phenotypic, functional, and molecular topography of a myeloerythroid progenitor cell hierarchy. Cell stem cell 2007, 1(4): 428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.005 18371379

11. Hu X, Pang Q, Shen Q, Liu H, He J, Wang J, et al. Ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 inhibits apoptosis by suppressing the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in Raw264.7 cells. International journal of molecular medicine 2014, 33(6): 1539–1546. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1728 24714921

12. Kwon J, Cho HJ, Han SH, No JG, Kwon JY, Kim H. A novel LZAP-binding protein, NLBP, inhibits cell invasion. The Journal of biological chemistry 2010, 285(16): 12232–12240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065920 20164180

13. Liu D, Wang WD, Melville DB, Cha YI, Yin Z, Issaeva N, et al. Tumor suppressor Lzap regulates cell cycle progression, doming, and zebrafish epiboly. Dev Dyn 2011, 240(6): 1613–1625. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22644 21523853

14. Tanaka Y, Kurosaki M, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, et al. Genome-wide association study identified ITPA/DDRGK1 variants reflecting thrombocytopenia in pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20(17): 3507–3516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr249 21659334

15. van Galen P, Kreso A, Mbong N, Kent DG, Fitzmaurice T, Chambers JE, et al. The unfolded protein response governs integrity of the haematopoietic stem-cell pool during stress. Nature 2014, 510(7504): 268–272. doi: 10.1038/nature13228 24776803

16. Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2012, 13(2): 89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270 22251901

17. Miharada K, Sigurdsson V, Karlsson S. Dppa5 improves hematopoietic stem cell activity by reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell reports 2014, 7(5): 1381–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.056 24882002

18. Lee JW, Choi HS, Gyuris J, Brent R, Moore DD. Two classes of proteins dependent on either the presence or absence of thyroid hormone for interaction with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 1995, 9(2): 243–254. 7776974

19. Jung DJ, Sung HS, Goo YW, Lee HM, Park OK, Jung SY, et al. Novel transcription coactivator complex containing activating signal cointegrator 1. Molecular and cellular biology 2002, 22(14): 5203–5211. 12077347

20. Bauer A, Mikulits W, Lagger G, Stengl G, Brosch G, Beug H. The thyroid hormone receptor functions as a ligand-operated developmental switch between proliferation and differentiation of erythroid progenitors. The EMBO journal 1998, 17(15): 4291–4303. 9687498

21. Angelin-Duclos C, Domenget C, Kolbus A, Beug H, Jurdic P, Samarut J. Thyroid hormone T3 acting through the thyroid hormone alpha receptor is necessary for implementation of erythropoiesis in the neonatal spleen environment in the mouse. Development 2005, 132(5): 925–934. 15673575

22. Kendrick TS, Payne CJ, Epis MR, Schneider JR, Leedman PJ, Klinken SP, et al. Erythroid defects in TRalpha-/ - mice. Blood 2008, 111(6): 3245–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101105 18203951

23. Bauer A, Tronche F, Wessely O, Kellendonk C, Reichardt HM, Steinlein P, et al. The glucocorticoid receptor is required for stress erythropoiesis. Genes & development 1999, 13(22): 2996–3002.

24. Evans T. Regulation of hematopoiesis by retinoid signaling. Experimental hematology 2005, 33(9): 1055–1061. 16140154

25. Sanchez-Aguilera A, Arranz L, Martin-Perez D, Garcia-Garcia A, Stavropoulou V, Kubovcakova L, et al. Estrogen signaling selectively induces apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid neoplasms without harming steady-state hematopoiesis. Cell stem cell 2014, 15(6): 791–804. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.002 25479752

26. Zhang Y, Zhang M, Wu J, Lei G, Li H. Transcriptional regulation of the Ufm1 conjugation system in response to disturbance of the endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and inhibition of vesicle trafficking. PLoS One 2012, 7(11): e48587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048587 23152784

27. Zhu X, Wang Y, Pi W, Liu H, Wickrema A, Tuan D. NF-Y recruits both transcription activator and repressor to modulate tissue - and developmental stage-specific expression of human gamma-globin gene. PLoS One 2012, 7(10): e47175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047175 23071749

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin TransporterČlánek Exocyst-Dependent Membrane Addition Is Required for Anaphase Cell Elongation and Cytokinesis inČlánek Spindle-F Is the Central Mediator of Ik2 Kinase-Dependent Dendrite Pruning in Sensory Neurons

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 11

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Agricultural Genomics: Commercial Applications Bring Increased Basic Research Power

- Ernst Rüdin’s Unpublished 1922-1925 Study “Inheritance of Manic-Depressive Insanity”: Genetic Research Findings Subordinated to Eugenic Ideology

- Convergent Evolution During Local Adaptation to Patchy Landscapes

- The Locus Controls Age at Maturity in Wild and Domesticated Atlantic Salmon ( L.) Males

- A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin Transporter

- Absence of Maternal Methylation in Biparental Hydatidiform Moles from Women with Maternal-Effect Mutations Reveals Widespread Placenta-Specific Imprinting

- Calibrating the Human Mutation Rate via Ancestral Recombination Density in Diploid Genomes

- Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Acts in the Mushroom Body to Negatively Regulate Sleep

- Connecting Replication and Repair: YoaA, a Helicase-Related Protein, Promotes Azidothymidine Tolerance through Association with Chi, an Accessory Clamp Loader Protein

- UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

- Mosaic and Intronic Mutations in Explain the Majority of TSC Patients with No Mutation Identified by Conventional Testing

- Members of the Epistasis Group Contribute to Mitochondrial Homologous Recombination and Double-Strand Break Repair in

- QTL Mapping of Sex Determination Loci Supports an Ancient Pathway in Ants and Honey Bees

- Genetic Interactions Implicating Postreplicative Repair in Okazaki Fragment Processing

- Genomics of Cancer and a New Era for Cancer Prevention

- Adaptation to High Ethanol Reveals Complex Evolutionary Pathways

- Dynamics of Transcription Factor Binding Site Evolution

- Exocyst-Dependent Membrane Addition Is Required for Anaphase Cell Elongation and Cytokinesis in

- Enhancer Runaway and the Evolution of Diploid Gene Expression

- Cattle Sex-Specific Recombination and Genetic Control from a Large Pedigree Analysis

- Drosophila Mutants Model Cornelia de Lange Syndrome in Growth and Behavior

- Pleiotropic Effects of Immune Responses Explain Variation in the Prevalence of Fibroproliferative Diseases

- Leaderless Transcripts and Small Proteins Are Common Features of the Mycobacterial Translational Landscape

- Tissue-Specific Effects of Reduced β-catenin Expression on Mutation-Instigated Tumorigenesis in Mouse Colon and Ovarian Epithelium

- Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin

- Mapping of Craniofacial Traits in Outbred Mice Identifies Major Developmental Genes Involved in Shape Determination

- Conserved Genetic Interactions between Ciliopathy Complexes Cooperatively Support Ciliogenesis and Ciliary Signaling

- Metabolomic Quantitative Trait Loci (mQTL) Mapping Implicates the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

- DNA Repair Cofactors ATMIN and NBS1 Are Required to Suppress T Cell Activation

- Spindle-F Is the Central Mediator of Ik2 Kinase-Dependent Dendrite Pruning in Sensory Neurons

- Ernst Rüdin and the State of Science

- ABCs of Insect Resistance to Bt

- Epigenetic Control of O-Antigen Chain Length: A Tradeoff between Virulence and Bacteriophage Resistance

- Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

- The Fanconi Anemia Pathway Protects Genome Integrity from R-loops

- Controls Quantitative Variation in Maize Kernel Row Number

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Golden Retrievers Identifies Germ-Line Risk Factors Predisposing to Mast Cell Tumours

- Insect Resistance to Toxin Cry2Ab Is Conferred by Mutations in an ABC Transporter Subfamily A Protein

- A Cytosine Methytransferase Modulates the Cell Envelope Stress Response in the Cholera Pathogen

- Conserved piRNA Expression from a Distinct Set of piRNA Cluster Loci in Eutherian Mammals

- The Multi-allelic Genetic Architecture of a Variance-Heterogeneity Locus for Molybdenum Concentration in Leaves Acts as a Source of Unexplained Additive Genetic Variance

- The lncRNA Controls Cryptococcal Morphological Transition

- Sae2 Function at DNA Double-Strand Breaks Is Bypassed by Dampening Tel1 or Rad53 Activity

- A Tandem Duplicate of Anti-Müllerian Hormone with a Missense SNP on the Y Chromosome Is Essential for Male Sex Determination in Nile Tilapia,

- Ectodysplasin/NF-κB Promotes Mammary Cell Fate via Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

- The QTL within the Complex Involved in the Control of Tuberculosis Infection in Mice Is the Classical Class II Gene

- Identifying Loci Contributing to Natural Variation in Xenobiotic Resistance in

- Variation in Rural African Gut Microbiota Is Strongly Correlated with Colonization by and Subsistence

- A Flexible, Efficient Binomial Mixed Model for Identifying Differential DNA Methylation in Bisulfite Sequencing Data

- Competition between Heterochromatic Loci Allows the Abundance of the Silencing Protein, Sir4, to Regulate Assembly of Heterochromatin

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

- Metabolomic Quantitative Trait Loci (mQTL) Mapping Implicates the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

- Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin

- Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání