-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaInverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons

Class 1 integrons are widespread genetic elements that allow bacteria to capture and express gene cassettes that are usually promoterless. These integrons play a major role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance among Gram-negative bacteria. They typically consist of a gene (intI) encoding an integrase (that catalyzes the gene cassette movement by site-specific recombination), a recombination site (attI1), and a promoter (Pc) responsible for the expression of inserted gene cassettes. The Pc promoter can occasionally be combined with a second promoter designated P2, and several Pc variants with different strengths have been described, although their relative distribution is not known. The Pc promoter in class 1 integrons is located within the intI1 coding sequence. The Pc polymorphism affects the amino acid sequence of IntI1 and the effect of this feature on the integrase recombination activity has not previously been investigated. We therefore conducted an extensive in silico study of class 1 integron sequences in order to assess the distribution of Pc variants. We also measured these promoters' strength by means of transcriptional reporter gene fusion experiments and estimated the excision and integration activities of the different IntI1 variants. We found that there are currently 13 Pc variants, leading to 10 IntI1 variants, that have a highly uneven distribution. There are five main Pc-P2 combinations, corresponding to five promoter strengths, and three main integrases displaying similar integration activity but very different excision efficiency. Promoter strength correlates with integrase excision activity: the weaker the promoter, the stronger the integrase. The tight relationship between the aptitude of class 1 integrons to recombine cassettes and express gene cassettes may be a key to understanding the short-term evolution of integrons. Dissemination of integron-driven drug resistance is therefore more complex than previously thought.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000793

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000793Summary

Class 1 integrons are widespread genetic elements that allow bacteria to capture and express gene cassettes that are usually promoterless. These integrons play a major role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance among Gram-negative bacteria. They typically consist of a gene (intI) encoding an integrase (that catalyzes the gene cassette movement by site-specific recombination), a recombination site (attI1), and a promoter (Pc) responsible for the expression of inserted gene cassettes. The Pc promoter can occasionally be combined with a second promoter designated P2, and several Pc variants with different strengths have been described, although their relative distribution is not known. The Pc promoter in class 1 integrons is located within the intI1 coding sequence. The Pc polymorphism affects the amino acid sequence of IntI1 and the effect of this feature on the integrase recombination activity has not previously been investigated. We therefore conducted an extensive in silico study of class 1 integron sequences in order to assess the distribution of Pc variants. We also measured these promoters' strength by means of transcriptional reporter gene fusion experiments and estimated the excision and integration activities of the different IntI1 variants. We found that there are currently 13 Pc variants, leading to 10 IntI1 variants, that have a highly uneven distribution. There are five main Pc-P2 combinations, corresponding to five promoter strengths, and three main integrases displaying similar integration activity but very different excision efficiency. Promoter strength correlates with integrase excision activity: the weaker the promoter, the stronger the integrase. The tight relationship between the aptitude of class 1 integrons to recombine cassettes and express gene cassettes may be a key to understanding the short-term evolution of integrons. Dissemination of integron-driven drug resistance is therefore more complex than previously thought.

Introduction

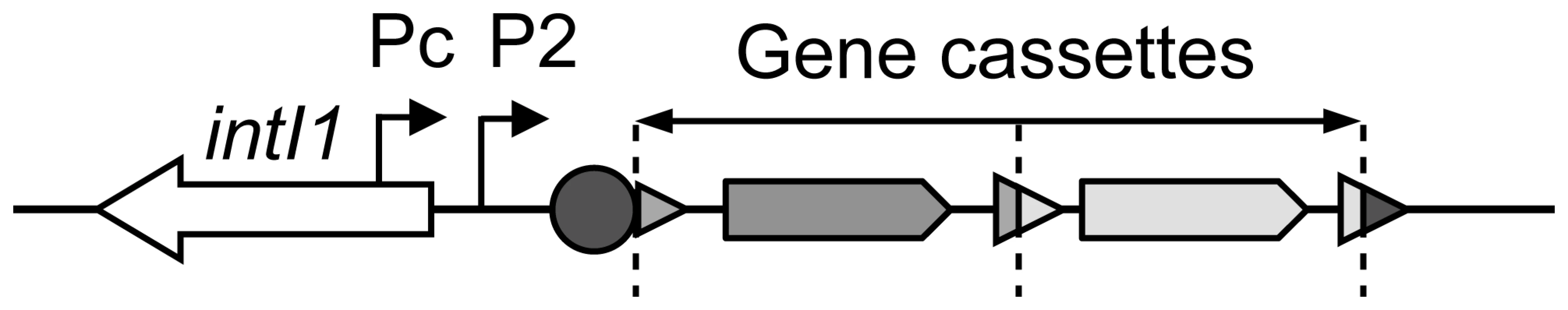

Integrons are natural genetic elements that can acquire, exchange and express genes within gene cassettes. The integron platform is composed of a gene, intI, that encodes a site-specific recombinase, IntI, a recombination site, attI, and a functional promoter, Pc, divergent to the integrase gene [1] (Figure 1). Gene cassettes are small mobile units composed of one coding sequence and a recombination site, attC. Integrons exchange gene cassettes through integrase-catalyzed site-specific recombination between attI and attC sites, resulting in the insertion of the gene cassette at the attI site, or between two attC sites, leading to the excision of the gene cassette(s) from the gene cassette array [2]–[6]. Multi-resistant integrons (MRI) contain up to eight gene cassettes encoding antibiotic resistance. To date, more than 130 gene cassettes have been described, conferring resistance to almost all antibiotic classes [7]. MRI play a major role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance among Gram-negative bacteria, through horizontal gene transfer [8]. Five classes of MRI have been described on the basis of the integrase coding sequence, class 1 being the most prevalent [8].

Fig. 1. General structure of a class 1 integron.

Coding sequences are indicated by arrows, attC cassette recombination sites by triangles, the integron recombination site attI1 by a circle, and the gene cassette promoters Pc and P2 by broken arrows. Dotted vertical bars represent gene cassette boundaries. Gene cassettes are usually promoterless, and their genes are transcribed from the Pc promoter, as in an operon (Figure 1), the level of transcription depending on their position within the integron [9],[10]. Among class 1 MRIs, several Pc variants have been defined on the basis of their −35 and −10 hexamer sequences. Four Pc variants have been named according to their sequence homology with the σ70 promoter consensus and their estimated respective strengths, as follows: PcS for ‘Strong’, PcW for ‘Weak’ (PcS being 30-fold stronger than PcW), PcH1 for Hybrid 1 and PcH2 for Hybrid 2, these two latter Pc variants containing the −35 and −10 hexamers of PcW and PcS in opposite combinations (Table 1), and having intermediate strengths [11]–[13]. More recently, a new variant was reported to be significantly stronger than PcS [14], and we therefore named it ‘Super-Strong’ or PcSS. Three other Pc variants have been described but their strength has not been determined; for simplicity, we named these Pc promoters PcIn42, PcIn116 and PcPUO, as they are carried by integrons In42 and In116 and by plasmid pUO901, respectively [15]–[17]. Nesvera and co-workers found a C to G mutation 2 bp upstream of the −10 hexamer in PcW and showed that this mutation increased promoter efficiency by a factor of 5 [18]. This mutation creates a ‘TGN’ extended −10 motif that is known to increase the transcription efficiency of σ70 promoters in E. coli [19]. Also, class 1 integrons occasionally harbor a second functional promoter named P2, located in the attI site and created by the insertion of three G residues, optimizing the spacing (17 bp) between potential −35 and −10 hexamer sequences [9] (Figure 1). Given the diversity of Pc variants and the range of their respective strengths, an identical array of gene cassettes should be differently expressed depending on the Pc variant present in the integron platform. However, the distribution of Pc variants among the numerous class 1 integrons has never been comprehensively studied.

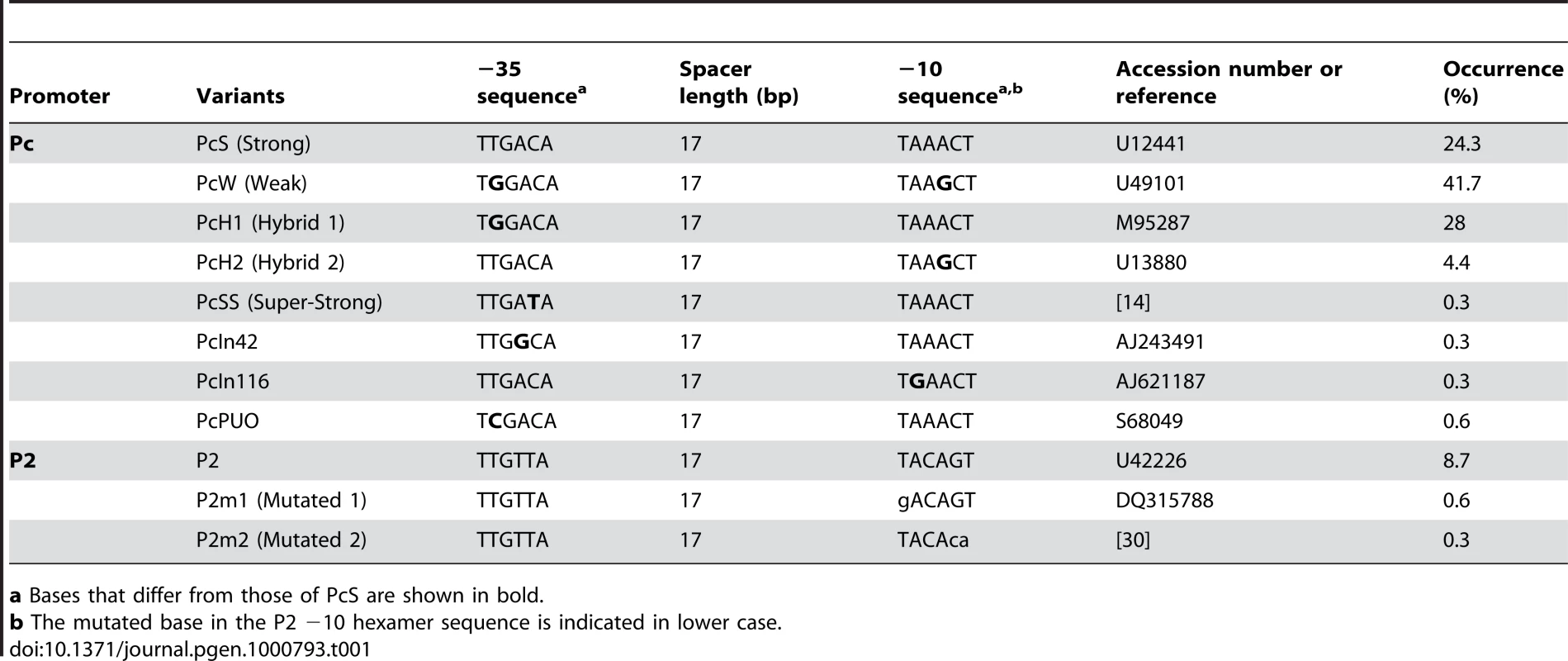

Tab. 1. Pc variants and P2 promoter sequences found in class 1 integrons.

a Bases that differ from those of PcS are shown in bold. In class 1 MRIs, the Pc promoter is located within the integrase coding sequence (Figure 1). Some of the base substitutions in the −35 and/or −10 hexamer sequences defining the different Pc variants actually correlate with amino acid changes in the IntI1 sequence. These variations in the IntI1 protein sequence could potentially influence integrase recombination activity and define different IntI1 catalytic variants.

We first performed an extensive in silico examination of all class 1 integron sequences available in databases in order to determine the prevalence of Pc variants and, therefore, the prevalence of IntI1 variants. We then estimated the strength of all Pc variants and Pc-P2 combinations in the same reporter gene assay, as well as the excision and integration activity of the main IntI1 variants. We found a very unequal distribution of the Pc variants, and a negative correlation between the strength of the Pc variant and the recombination efficiency of the corresponding IntI1 protein.

Results

Distribution of the different gene cassette promoter variants

We analyzed the sequences of 321 distinct class 1 integrons containing the complete sequences of both gene cassette arrays and Pc-P2 promoters (see Materials and Methods). When considering only the −35 and −10 hexamer sequences, we found no more than the eight variants identified previously. However, their distribution was highly uneven, four variants (PcW, PcS, PcH1 and PcH2) totalling 98.4% of the sequences analyzed (Table 1). The most frequent Pc variant was PcW (41.7%), followed by PcH1 (28%), PcS (24.3%) and PcH2 (4.4%). The four other Pc variants, all more recently described, were extremely rare (Table 1). The most prevalent Pc variant among class 1 integrons appeared to be the weak PcW, but in 58% of the analyzed PcW-containing integrons this promoter was associated with either a ‘TGN’ extended −10 motif [20] (hereafter designated variant PcWTGN-10) or the second gene cassette promoter P2 (Table 2). These two features were much less frequent with the other Pc variants (Table 2). The dataset also contained two other extremely rare Pc configurations, designated PcWTAN-10 and PcH1TTN-10, in which the second base upstream of the −10 hexamer was replaced by an A or a T instead of C, respectively, as well as two other rare forms of P2, designated P2m1 and P2m2, for ‘P2 mutated form 1’ and ‘P2 mutated form 2’ (Table 1 and Table 2).

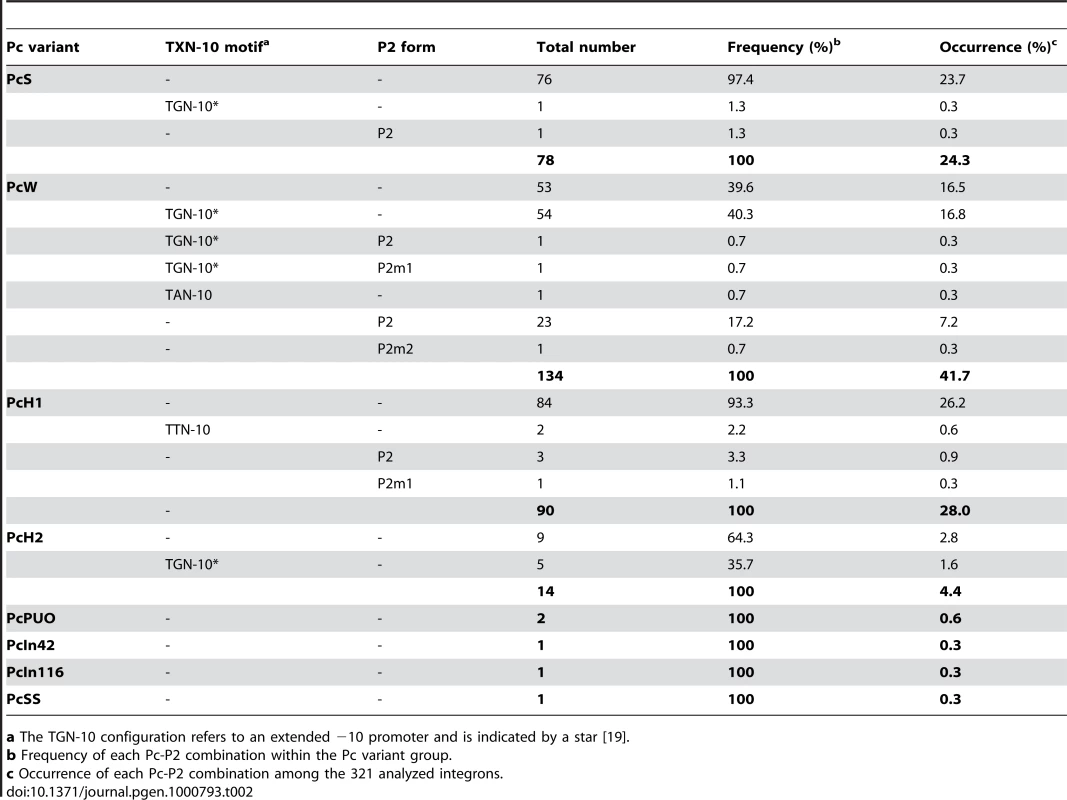

Tab. 2. Combinations of class 1 integron Pc-Pc2 sequences.

a The TGN-10 configuration refers to an extended −10 promoter and is indicated by a star [19]. Altogether, on the basis of the −35 and −10 hexamers and the sequence upstream of the −10 box, we identified 13 Pc variants, four of which were also found associated with a form of the P2 promoter (Table 2).

Relative strengths of gene cassette promoter variants

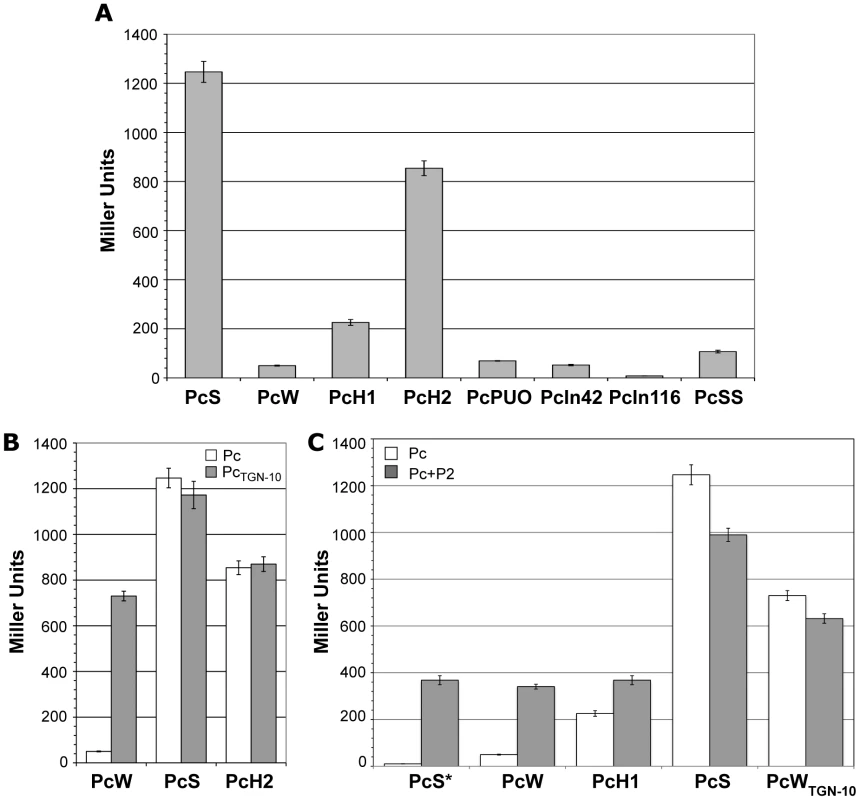

Until recently, the promoter strength of only 4 of the 8 known variants (PcSS, PcS, PcH1 and PcW) had been estimated, but variants strength had never been compared in the same assay [11],[14]. We therefore examined the capacity of all the Pc variants and the different Pc-P2 configurations to drive the expression of the lacZ reporter gene cloned in a transcriptional fusion with a 254-bp fragment containing the Pc variant and the P2 promoter region (see Materials and Methods). We found, in agreement with the results of a previous study [11] and those of another study published during the course of this work [13], that PcS was about 25-fold stronger than PcW and 4.5-fold stronger than PcH1, while PcH2 lay between PcH1 and PcS, being 3.8-fold stronger than PcH1. PcPUO and PcIn42 were of similar strength to PcW, and PcIn116 was very weak (Figure 2A). The PcSS variant, previously described as being stronger than PcS [14], was about 12-fold less efficient in our experimental conditions (Figure 2A). This latter result was not wholly unexpected, as PcSS contains a down-promoter mutation in the −35 hexamer relative to PcS (Table 1; [21]).

Fig. 2. Strength of class 1 Pc variants.

(A) Pc promoter strength was estimated by measuring the β-galactosidase activity of Pc-lacZ transcriptional fusions. (B) β-galactosidase activities of Pc-lacZ fusions for different Pc variants in either their wild-type configuration (white bars) or bearing the TGN-10 motif (grey bars). (C) Same as (B), but for Pc variants in combination with P2. PcS* designates an artificially mutated PcS variant that was combined with P2 to serve as a control for specific P2 promoter activity. At least five independent assays were performed for each variant and in each experiment. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. We found that the presence of the TGN-10 motif increased PcW efficiency 15-fold, approaching that of PcH2, whereas it had no significant effect on PcS or PcH2 activity (Figure 2B), probably because these promoters are already maximally efficient. On the other hand, the C to A mutation in PcWTAN-10 severely reduced PcW activity (as already observed for the activity of an Escherichia coli promoter [19]), and the C to T mutation in PcH1TTN-10 slightly increased PcH1 efficiency (1.7-fold; data not shown).

To evaluate the contribution of P2 to gene cassette expression, we first created transcriptional lacZ fusion with sequences containing a combination of an inactive PcS (hereafter named PcS*, see Materials and Methods) and the P2 variants, in order to assess their specific strength. We found that P2 was active and 7-fold stronger than PcW (Figure 2C), in keeping with previous studies [11]. P2m1 and P2m2 appeared to be inactive (data not shown) and their influence on gene cassette expression was not investigated further. When the weakest Pc variants (PcW and PcH1) were associated with P2, β-galactosidase activity was increased but was equivalent to that of P2, indicating that, in the PcW-P2 and PcH1-P2 combinations, PcW and PcH1 do not contribute significantly to the expression of gene cassettes, which is mainly driven by P2. By contrast, when P2 was associated with the strongest variants, PcS and PcWTGN-10, β-galactosidase activity decreased slightly (Figure 2C). A recent report described a small increase in the expression of a gene cassette when PcS was combined with P2 [13], but these authors used different methods to measure promoter strength, which may explain the discrepancy with our results.

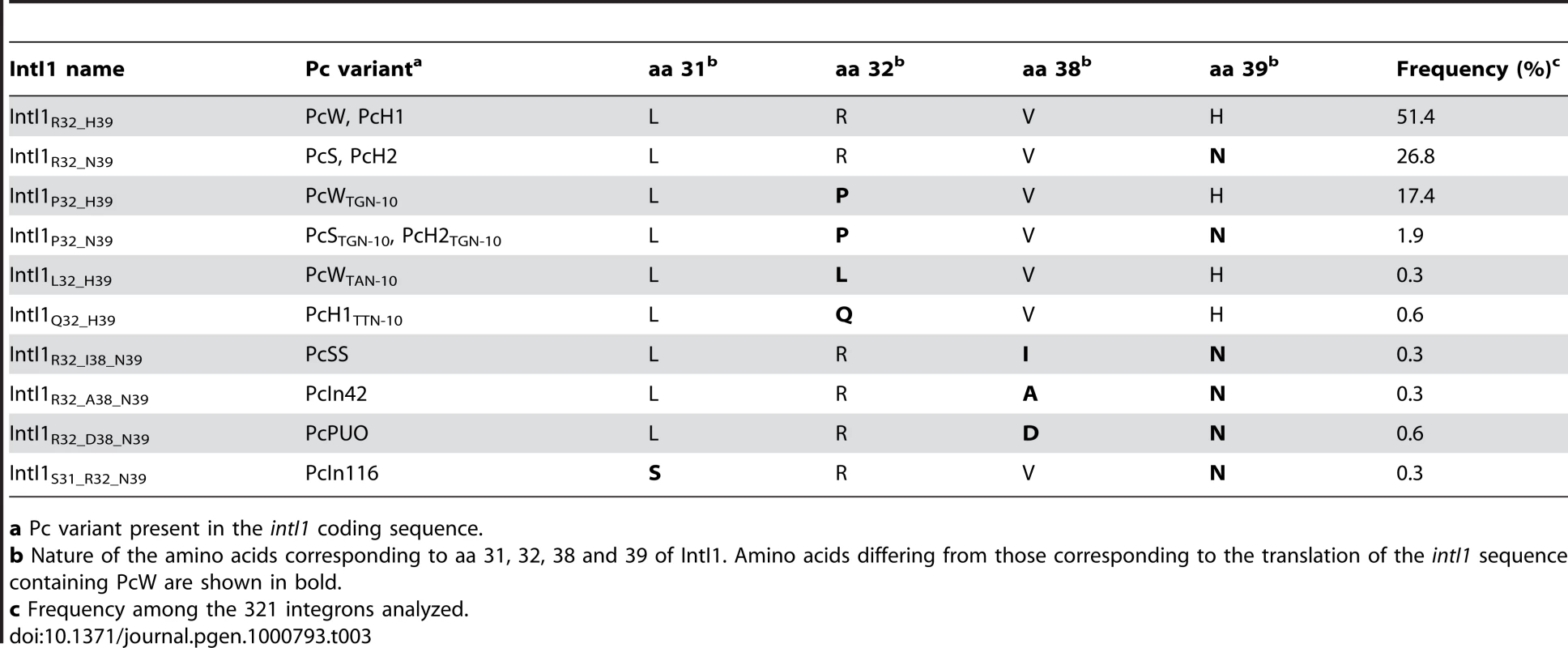

The nature of the Pc variant defines several IntI1 variants

In class 1 MRIs, Pc is located within the intI1 coding sequence, and several of the substitutions generating the different Pc variants affect the IntI1 amino acid (aa) sequence. The aa changes involve aa 32 or 39 for the main variants and aa 31, 32, 38 and/or 39 for the rare variants (Table 3). Some Pc variants produce the same IntI1 variant, e.g. PcW/PcH1 and PcS/PcH2 (Table 3). Altogether, 10 IntI1 variants are generated from 13 Pc variants, three of which (IntI1R32_H39, IntI1R32_N39 and IntI1P32_H39) represent almost 96% of the IntI1 variants (Table 3).

Tab. 3. Correlation between the Pc variant configuration and amino acid changes in the integrase sequence.

a Pc variant present in the intI1 coding sequence. The different IntI1 variants display a wide range of excision activities but similar integration activities

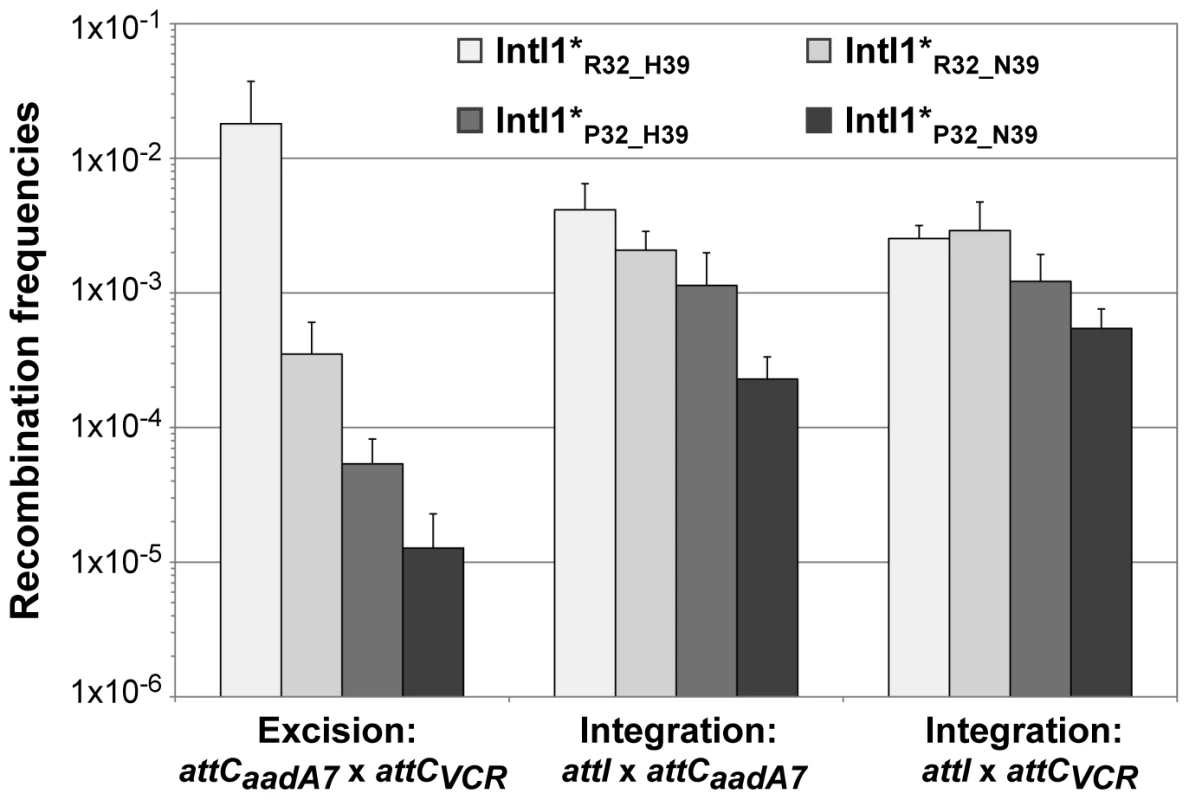

In order to estimate the impact of the aa differences on IntI1 activity, we first cloned the intI1 gene of the three main IntI1 variants, IntI1R32_H39, IntI1R32_N39 and IntI1P32_H39, under the control of the arabinose-inducible promoter ParaB (see Materials and Methods). However, we anticipated that the two convergent promoters, namely Pc (contained in the intI sequence) and ParaB, might interfere with each other. Thus, to estimate IntI1 protein recombination activity independently of potential promoter interference, we introduced mutations that inactivated the Pc promoters without affecting the IntI1 aa sequence (see Materials and Methods). The resulting integrases were named IntI1*R32_H39, IntI1*R32_N39 and IntI1*P32_H39 (Table 3). We then estimated the excision activity of these integrases by measuring their capacity to catalyze recombination between two attC sites located on a synthetic array of two cassettes, attCaadA7-cat(T4)-attCVCR-aac(6′)-Ib, and resulting in the deletion of the synthetic cassette, cat(T4)-attCVCR, and the expression of tobramycin resistance mediated by the gene aac(6′)-Ib (see Materials and Methods; [22]). As shown in Figure 3, the three integrases exhibited very different excision activities (1.8×10−2 to 1.3×10−5), IntI1*P32_H39 and IntI1*R32_N39 being respectively 336 - and 51-fold less efficient than IntI1*R32_H39. Thus, replacing R32 by P32, or H39 by N39 drastically reduces the capacity of the integrase to promote recombination between the attCaadA7 and attCVCR sites. The strongest effect was observed when a proline was present at position 32. P32 is also found in the integrase IntI1P32_N39, a much less frequent variant of IntI1 (Table 3). We therefore created this latter IntI1 variant and measured its excision activity. IntI1*P32_N39 was 27-fold less active than IntI1*R32_N39, showing the same negative effect of P32 on excision activity (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Recombination activities of the main IntI1 variants.

IntI1 excision recombination activity was estimated by determining the frequency of emergence of the tobramycin resistance phenotype as a result of recombination between the attC sites of the attCaadA7-catT4-attCVCR-aac(6′)-Ib array, leading to the deletion of the synthetic cassette catT4-attCVCR and expression of the tobramycin resistance gene aac(6′)-Ib. IntI1 integration recombination activity was estimated by determining the frequency of emergence of cointegrate of two plasmids, one carrying an attI site and the other an attC site. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean for at least seven independent assays. Class 1 integrase is also able to catalyze the integration of gene cassettes by promoting recombination between attI and attC sites [5]. We therefore tested the ability of the different IntI1 variants to catalyze recombination between attI and the two attC sites used for the excision activity assay (attCaadA7 and attCVCR), in an assay based on suicide conjugative transfer previously developed [6] and since extensively used [23]–[25] (see Materials and Methods). Surprisingly, the range of integration activity of the four IntI variants tested in this study was rather narrow (4.5×10−3 to 2.3×10−4) compared to their excision activity, independently of the nature of the attC site (Figure 3). IntI1*R32_H39 and IntI1*R32_N39 exhibited similar integration activities in the two reactions performed, and the R32P substitution appeared to be detrimental for the activity of both integrases, but far less than for their excision activity. This effect seemed a bit stronger with IntI1*P32_N39 than with IntI1*P32_H39 (integration frequency was reduced by roughly 8-fold compared to 3-fold, respectively; Figure 3).

To show that the observed differences in excision and integration activities of the four integrases tested were not due to variations in the amounts of integrase but indeed to the nature of the aa at positions 32 and 39, we performed SDS-Page western blot analysis. We found that IntI1*R32_H39, IntI1*R32_N39 and IntI1*P32_N39 were equally produced and that IntI1*P32_H39 was slightly more strongly expressed in our experimental conditions (Figure S1 and Text S1). However, the latter had one of the weakest recombination activities (Figure 3). Therefore, the observed differences in excision activity among the IntI1 variants were due not to differences in protein abundance but to differences in protein activity and/or folding.

Discussion

In this study we found marked polymorphism of the gene cassette promoter Pc (13 variants), corresponding to ten variants of the class 1 integrase IntI1. The 13 Pc variants were defined on the basis of the −35 and −10 hexamers and the sequence upstream of the −10 box. Indeed almost 20% of the 321 integrons analyzed here harbored a TGN-10 motif that characterized an extended −10 promoter. This feature was mainly associated with the weak PcW variant (41.8% of PcW-containing integrons) and increased the efficiency of this promoter by a factor of 15. In view of its frequency and its strength difference relative to PcW, we propose that this promoter, designated PcWTGN-10, be considered as a Pc variant distinct from PcW. Furthermore, 9% of the 321 integrons contained the P2 promoter, which was almost exclusively associated with the PcW variant (17.2% of PcW-containing integrons, Table 2). As in previous studies, we found that transcriptional activity was mainly driven by P2 in the PcW-P2 combination [9],[11]. We also observed the same effect with PcH1.

Altogether, there are no fewer than 20 distinct gene cassette promoter configurations for class 1 integrons, but their frequencies are very different. Five main combinations emerged from the dataset, defining five levels of promoter strength. The distribution and strength of the gene cassette promoters were as follows: PcW-P2<PcW≈PcWTGN-10<PcS≈PcH1 (distribution, Table 2) and PcW<PcH1<PcW-P2<PcWTGN-10<PcS (respectively 4.5-, 7-, 15 - and 25-fold more active than PcW; Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The multiplicity of gene-cassette promoters displaying different strengths indicates that a given antibiotic resistance gene cassette will be differently expressed depending on which Pc variant is present in the integron. For example, we used an E. coli strain containing a class 1 integron with PcW, PcS or PcWTGN-10, and with aac(6′)-Ib as the first cassette. The tobramycin MIC was 8-fold higher when the cassette was expressed from PcS or PcWTGN-10 than from PcW (data not shown). Our findings indicate that, in class 1 integrons, gene cassette expression is mainly controlled by the strongest Pc variants (PcS, PcH2, PcWTGN-10 and PcW-P2, in 55% of cases).

Another important and previously unnoticed feature of class 1 integrons is the variability of the IntI1 primary sequence linked to the diversity of Pc variants. Among the 10 IntI1 variants identified, three (IntI1R32_H39, IntI1R32_N39 and IntI1P32_H39) accounted for almost 96% of class 1 integrases (Table 3). We found that these three main IntI1s displayed similar integration efficiencies, independently of the attC sites tested, whereas they had extremely different excision activities, depending on the nature of the amino acid at position 32 and/or 39. The R32P and H39N substitutions each drastically reduced the capacity of the integrase to promote recombination between the attCaadA7 and attCVCR sites (by 336 - and 51-fold, respectively). In the integrase of the Vibrio cholerae chromosomal integron VchIntIA, the aa found at the position equivalent to residue 32 is basic, while the aa at position equivalent to residue 39 is a histidine (K21 and H28, respectively [24]), showing that, among IntI1 variants, IntI1R32_H39 is its closest relative. The crystal structure of VchIntIA bound to an attC substrate showed that these amino acids are located within an α-helix involved in attC binding [26]. This α-helix is conserved in the predicted structure of IntI1 and presumably plays the same role in recombination [24]. Thus, mutations of aa 32 and 39 in IntI1 might perturb the binding and thus undermine the recombination efficiency of attC×attC. The positively charged aa R32 may also play a role in the interaction with the attC site in the attI×attC recombination reaction. Indeed, a R32P substitution in both IntI1*R32_H39 and IntI1*R32_N39 reduced the integration frequency, but to a lesser extent than in an excision reaction (Table 3 and Figure 3). In contrast, aa H39 does not seem to be involved in the integration reaction. The attI×attC and attC×attC recombination reactions may thus involve different regions of the integrase. Indeed, Demarre and collaborators isolated two IntI1R32_H39 mutants, IntI1P109L and IntI1D161G, that showed much higher integration efficiencies [24].

Interestingly, we found a correlation between Pc strength and integrase excision activity: the weaker the Pc variant, the more active the IntI1. Among the four integrases tested, IntI1R32_H39, which was the most prevalent IntI1 in our dataset (Table 3), had the most efficient excision activity and also displayed higher excision than integration activity. Integrons with this integrase contain either the PcW variant, leading to a weak expression of the gene cassette array, or the PcH1 variant, associated with slightly higher expression (4.5-fold). PcW-containing integrons could compensate for a low level of antibiotic resistance expression by the high excision efficiency of IntI1R32_H39, which confers a marked capacity for cassette rearrangement, in order to place the required gene cassette closer to Pc. In a recent study, Gillings et al suggested that chromosomal class 1 integrons from environmental β-proteobacteria might be ancestors of current clinical class 1 integrons [27]. The integrons they described all encoded IntI1R32_H39 and contained the PcW variant. We suspect that, under antibiotic selective pressure, these “ancestor” integrons may have evolved to enhance gene cassette expression, without modifying the potential for cassette reorganization, either through a single mutation (conversion of PcW to PcH1) or by the creation of a second promoter, P2, that is seven times more active. The high frequency of PcH1 (27.3%) likely reflects its successful selection. P2 probably arises less frequently, as it requires the insertion of three G. We have recently shown that the expression of IntI1 is regulated via the SOS response, a LexA binding site overlapping its promoter [22]. Interestingly, when P2 is created, the insertion of three G disrupts the LexA binding site, probably leading to constitutive expression of IntI1.

In a context of stronger antibiotic selective pressure, the need to express gene cassettes more efficiently could have led to the selection of more efficient Pc sequences (such as PcS and PcWTGN-10) at the expense of IntI1 excision activity, resulting in the stabilization of successful cassette arrays. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that integrons bearing IntI1R32_N39 or IntI1P32_H39 tend to harbor larger gene cassette arrays than those bearing IntI1R32_H39 (Figure S2).

The tight relationship between the aptitude of class 1 integrons to recombine and to express gene cassettes may be one key to understanding short-term integrase evolution. Different antibiotic selective pressures might select different evolutionary compromises. Thus, integron-driven drug resistance is more complex than previously thought.

Materials and Methods

Genbank class 1 integron sequence analysis

Compilation of the class 1 promoter sequences was performed in the entire Genbank nucleotide collection (nr/nt) using the alignment search tool BLASTn (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and the sequences of the intI1 and/or attI1 from the In40 integron as reference [28] (GenBank accession number AF034958). This data extraction was performed on 2009-02-01. Three other published but non-deposited sequences [14],[29],[30] were added to the 1351 sequences collected above. Of these 1351 sequences, only 434 contained both the Pc and P2 promoter sequences. Among the latter 434 sequences, we identified the integrons that displayed both identical gene cassette arrays and identical Pc/P2 sequences, independently of their bacterial origin. This analysis led to the isolation of 321 unique class 1 integron sequences that were further studied (Table S1).

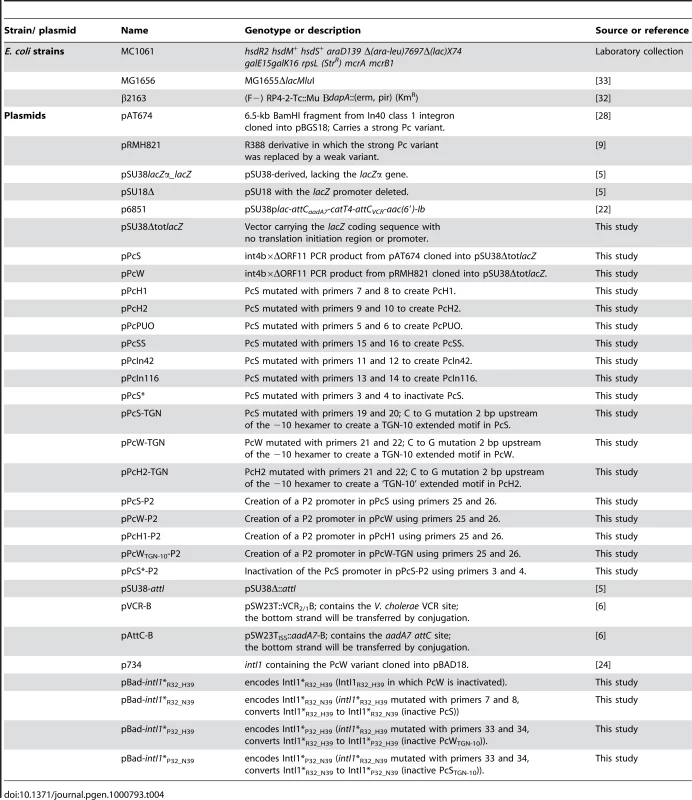

Bacteria and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 4. Cells were grown at 37°C in brain-heart infusion broth (BHI) or Luria Bertani broth (LB) supplemented when necessary with kanamycin (Km, 25 µg/ml), ampicillin (Amp, 100 µg/ml), tobramycin (Tobra, 10 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm 25 µg/ml), DAP (0.3 mM), glucose (1%), arabinose (0.2%).

Tab. 4. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

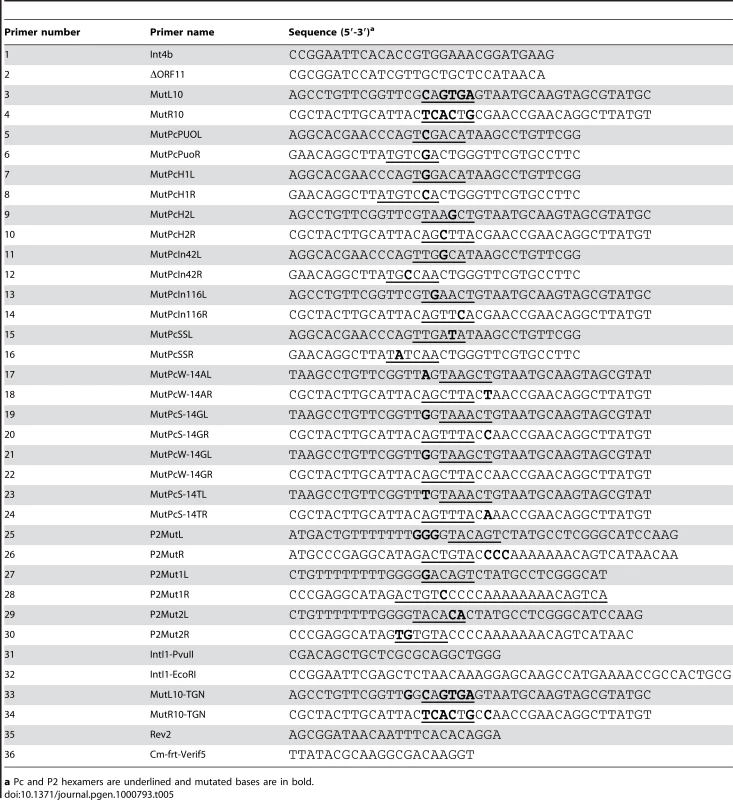

Assembly PCR

Mutations of the Pc and P2 promoter sequences were generated by assembly PCR with overlapping primers that contained the desired mutation and two external primers, int4b and ΔORF11 (Table 5). The two primary PCR products were then used in an equimolar ratio as templates for a second PCR step with the two external primers.

Tab. 5. Primers used in this study.

a Pc and P2 hexamers are underlined and mutated bases are in bold. Plasmid construction

Reporter vector pSU38ΔtotlacZ

The SacII-EcoRI region of pSU38lacZα_lacZ, which contains the promoter, the ribosome binding site (RBS) and the first codons of the lacZ gene, was replaced by the 255-bp SacII-EcoRI fragment of pSU18Δ [5] that contains the same first codons of lacZ but no transcriptional or translational signals.

lacZ transcriptional fusions

The PcS-lacZ and PcW-lacZ transcriptional fusions were constructed by cloning, into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pSU38ΔtotlacZ, a 264-bp fragment containing both the Pc and P2 sequences, amplified from pAT674 and pRMH821 respectively (Table 4). All the −lacZ fusions with the other Pc variant configurations or combinations were obtained by assembly PCR with specific primers, as described above. The pSU38ΔtotlacZ fusion plasmids are listed in Table 4. All cloned fragments were verified by sequencing. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Genosys and are listed in Table 5.

IntI1* expression vectors

The p734 plasmid carries the IntI1R32_H39 integrase under the control of the arabinose-inducible ParaB promoter [5]. The Pc −10 box, which lies within intI1 at positions corresponding to aa S30 and L31, was inactivated without modifying the IntI1 aa sequence, i.e. the codon mutation AGC to TCA conserved S30 and codon mutation TTA to CTG conserved L31. The Pc −10 box was inactivated by PCR assembly using p734 as template, internal primers 3 and 4, and external primers 31 and 32. The resulting plasmid, pBad-intI1*R32_H39, was used to create pBad-intI1*R32_N39 and pBad-intI1*P32_H39 by PCR assembly with the internal primers indicated in Table 4. Likewise, pBad-intI1*R32_N39 was used to create pBad-intI1*P32_N39. Cloned fragments were verified by sequencing.

β-galactosidase assay

Each transcriptional fusion plasmid was transformed into E. coli strain MC1061 to measure β-galactosidase enzyme activity. Assays were performed with 0.5-ml aliquots of exponential-phase cultures (OD600 = 0.6–0.8) as described by Miller [31] except that the incubation temperature was 37°C. Experiments were done at least 5 times for each strain.

Integrase excision activity assay

A synthetic array of two cassettes attCaadA7-cat(T4)-attCVCR-aac(6′)-Ib preceded by the lac promoter is carried on plasmid p6851. This construction confers chloramphenicol resistance from the cat gene encoding chloramphenicol acetyltransferase from Tn9, here followed by a phageT4 rho-independent terminator, to prevent transcriptional read-through. The excision assay is based on the capacity of the integrase to catalyze recombination between the attC sites, resulting in the deletion of the synthetic cassette cat(T4)-attCVCR and expression of the tobramycin resistance gene aac(6′)-Ib from the lac promoter [22]. IntI1 proteins were expressed from the pBad-intI1* plasmids. A stationary-phase liquid culture of E. coli strain MG1656, carrying both p6851 and one of the pBad-intI1*, grown over-day in LB broth supplemented with antibiotics and glucose, was diluted 100-fold in LB broth supplemented with antibiotics plus either glucose or arabinose and was grown overnight. Recombinants were selected on LB-Tobra plates. Excision frequency was measured by determining the ratio of TobraR to KmR colonies.

Integrase integration activity assay

The assay was based on the method described in [6] and since extensively used [23]–[25]. Conjugation is used to deliver the attC site carried onto a suicide vector from the R6K-based pSW family [32] into a recipient cell expressing the IntI1 integrase and carrying the attI site on a pSU38 plasmid derivative (all plasmids are listed in Table 4). Briefly, the RP4(IncPα) conjugation system uses the donor strain β2163 and the recipient MG1656, which does not carry the pir gene, and thus cannot sustain replication of pSW plasmids after conjugation. Recombination between attI and attC sites within the recipient cell leads to the formation of cointegrates between pSW and pSU38 plasmid. The number of recipient cells expressing the pSW marker (CmR) directly reflects the frequency of cointegrate formation. IntI1 proteins were expressed from the pBad-intI1* plasmids. Conjugation experiments were performed as previously described [5]. Integration activity was calculated as the ratio of transconjugants expressing the pSW marker CmR to the total number of recipient KmR clones. attC-attI cointegrate formation was checked by PCR with appropriate primers (primers 35 and 36; Table 5) on two randomly chosen clones per experiment. Background values were established by using recipient strains containing an empty pBad in place of the pBad-intI1*, and were 6×10−7 and 6×10−8 for the attI×attCVCR and attI×attCVCR assays, respectively. At least five experiments were performed for each recombination assay.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. StokesHW

HallRM

1989 A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol 3 1669 1683

2. CollisCM

HallRM

1992 Gene cassettes from the insert region of integrons are excised as covalently closed circles. Mol Microbiol 6 2875 2885

3. CollisCM

HallRM

1992 Site-specific deletion and rearrangement of integron insert genes catalyzed by the integron DNA integrase. J Bacteriol 174 1574 1585

4. CollisCM

RecchiaGD

KimMJ

StokesHW

HallRM

2001 Efficiency of recombination reactions catalyzed by class 1 integron integrase IntI1. J Bacteriol 183 2535 2542

5. BiskriL

BouvierM

GueroutAM

BoisnardS

MazelD

2005 Comparative study of class 1 integron and Vibrio cholerae superintegron integrase activities. J Bacteriol 187 1740 1750

6. BouvierM

DemarreG

MazelD

2005 Integron cassette insertion: a recombination process involving a folded single strand substrate. Embo J 24 4356 4367

7. PartridgeSR

TsafnatG

CoieraE

IredellJ

2009 Gene cassettes and cassette arrays in mobile resistance integrons. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33 757 784

8. MazelD

2006 Integrons: agents of bacterial evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 4 608 620

9. CollisCM

HallRM

1995 Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39 155 162

10. JacquierH

ZaouiC

Sanson-le PorsMJ

MazelD

BercotB

2009 Translation regulation of integrons gene cassette expression by the attC sites. Mol Microbiol 72 1475 1486

11. LevesqueC

BrassardS

LapointeJ

RoyPH

1994 Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for the antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene 142 49 54

12. BunnyKL

HallRM

StokesHW

1995 New mobile gene cassettes containing an aminoglycoside resistance gene, aacA7, and a chloramphenicol resistance gene, catB3, in an integron in pBWH301. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39 686 693

13. PapagiannitsisCC

TzouvelekisLS

MiriagouV

2009 Relative strengths of the class 1 integron promoter hybrid 2 and the combinations of strong and hybrid 1 with an active p2 promoter. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53 277 280

14. BrizioA

ConceicaoT

PimentelM

Da SilvaG

DuarteA

2006 High-level expression of IMP-5 carbapenemase owing to point mutation in the −35 promoter region of class 1 integron among Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents 27 27 31

15. HouangET

ChuYW

LoWS

ChuKY

ChengAF

2003 Epidemiology of rifampin ADP-ribosyltransferase (arr-2) and metallo-beta-lactamase (blaIMP-4) gene cassettes in class 1 integrons in Acinetobacter strains isolated from blood cultures in 1997 to 2000. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47 1382 1390

16. PowerP

GalleniM

Di ConzaJ

AyalaJA

GutkindG

2005 Description of In116, the first blaCTX-M-2-containing complex class 1 integron found in Morganella morganii isolates from Buenos Aires, Argentina. J Antimicrob Chemother 55 461 465

17. RiccioML

FranceschiniN

BoschiL

CaravelliB

CornagliaG

2000 Characterization of the metallo-beta-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of bla(IMP) allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44 1229 1235

18. NesveraJ

HochmannovaJ

PatekM

1998 An integron of class 1 is present on the plasmid pCG4 from gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol Lett 169 391 395

19. BurrT

MitchellJ

KolbA

MinchinS

BusbyS

2000 DNA sequence elements located immediately upstream of the −10 hexamer in Escherichia coli promoters: a systematic study. Nucleic Acids Res 28 1864 1870

20. BarneKA

BownJA

BusbySJ

MinchinSD

1997 Region 2.5 of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase sigma70 subunit is responsible for the recognition of the ‘extended-10’ motif at promoters. EMBO J 16 4034 4040

21. MoyleH

WaldburgerC

SusskindMM

1991 Hierarchies of base pair preferences in the P22 ant promoter. J Bacteriol 173 1944 1950

22. GuerinE

CambrayG

Sanchez-AlberolaN

CampoyS

ErillI

2009 The SOS response controls integron recombination. Science 324 1034

23. BouvierM

Ducos-GalandM

LootC

BikardD

MazelD

2009 Structural features of single-stranded integron cassette attC sites and their role in strand selection. PLoS Genet 5 e1000632 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000632

24. DemarreG

FrumerieC

GopaulDN

MazelD

2007 Identification of key structural determinants of the IntI1 integron integrase that influence attC×attI1 recombination efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res 35 6475 6489

25. FrumerieC

Ducos-GalandM

GopaulDN

MazelD

2009 The relaxed requirements of the integron cleavage site allow predictable changes in integron target specificity. Nucleic Acids Res doi:10.1093/nar/gkp990

26. MacDonaldD

DemarreG

BouvierM

MazelD

GopaulDN

2006 Structural basis for broad DNA-specificity in integron recombination. Nature 440 1157 1162

27. GillingsM

BoucherY

LabbateM

HolmesA

KrishnanS

2008 The evolution of class 1 integrons and the rise of antibiotic resistance. J Bacteriol 190 5095 5100

28. PloyMC

CourvalinP

LambertT

1998 Characterization of In40 of Enterobacter aerogenes BM2688, a class 1 integron with two new gene cassettes, cmlA2 and qacF. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42 2557 2563

29. YanoH

KugaA

OkamotoR

KitasatoH

KobayashiT

2001 Plasmid-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase (IMP-6) conferring resistance to carbapenems, especially meropenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45 1343 1348

30. LindstedtBA

HeirE

NygardI

KapperudG

2003 Characterization of class I integrons in clinical strains of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis from Norwegian hospitals. J Med Microbiol 52 141 149

31. MillerJH

1992 A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria Cold Spring Harbor, , N.Y. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

32. DemarreG

GueroutAM

Matsumoto-MashimoC

Rowe-MagnusDA

MarliereP

2005 A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPalpha) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res Microbiol 156 245 255

33. EspeliO

MoulinL

BoccardF

2001 Transcription attenuation associated with bacterial repetitive extragenic BIME elements. J Mol Biol 314 375 386

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70Článek Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse ModelČlánek Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin PathwayČlánek Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 1

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Irradiation-Induced Genome Fragmentation Triggers Transposition of a Single Resident Insertion Sequence

- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- Modeling of Environmental Effects in Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies and as Novel Loci Influencing Serum Cholesterol Levels

- Inverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons

- Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70

- Postnatal Survival of Mice with Maternal Duplication of Distal Chromosome 7 Induced by a / Imprinting Control Region Lacking Insulator Function

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse Model

- Understanding Gene Sequence Variation in the Context of Transcription Regulation in Yeast

- miR-30 Regulates Mitochondrial Fission through Targeting p53 and the Dynamin-Related Protein-1 Pathway

- Elevated Levels of the Polo Kinase Cdc5 Override the Mec1/ATR Checkpoint in Budding Yeast by Acting at Different Steps of the Signaling Pathway

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

- Co-Orientation of Replication and Transcription Preserves Genome Integrity

- A Comprehensive Map of Insulator Elements for the Genome

- Environmental and Genetic Determinants of Colony Morphology in Yeast

- U87MG Decoded: The Genomic Sequence of a Cytogenetically Aberrant Human Cancer Cell Line

- The MCM-Binding Protein ETG1 Aids Sister Chromatid Cohesion Required for Postreplicative Homologous Recombination Repair

- Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

- Differential Localization and Independent Acquisition of the H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 Chromatin Modifications in the Adult Germ Line

- Genetic Crossovers Are Predicted Accurately by the Computed Human Recombination Map

- Collaborative Action of Brca1 and CtIP in Elimination of Covalent Modifications from Double-Strand Breaks to Facilitate Subsequent Break Repair

- Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Novel Susceptibility Gene for Osteoporosis

- and Regulate Reproductive Habit in Rice

- Nonsense-Mediated Decay Enables Intron Gain in

- Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology

- The Systemic Imprint of Growth and Its Uses in Ecological (Meta)Genomics

- The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon

- Genotype and Gene Expression Associations with Immune Function in

- The Elongator Complex Regulates Neuronal α-tubulin Acetylation

- Rising from the Ashes: DNA Repair in

- Mis-Spliced Transcripts of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α6 Are Associated with Field Evolved Spinosad Resistance in (L.)

- BRIT1/MCPH1 Is Essential for Mitotic and Meiotic Recombination DNA Repair and Maintaining Genomic Stability in Mice

- Non-Coding Changes Cause Sex-Specific Wing Size Differences between Closely Related Species of

- Evidence for Pervasive Adaptive Protein Evolution in Wild Mice

- Evolutionary Mirages: Selection on Binding Site Composition Creates the Illusion of Conserved Grammars in Enhancers

- VEZF1 Elements Mediate Protection from DNA Methylation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání