-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaJewish pharmacists in pharmacies of interwar Czechoslovakia and their lives during World War II

Authors: T. Arndt

Authors place of work: Department of Social and Clinical Pharmacy of Faculty of Pharmacy in Hradec Králové, Charles University in Czech Republic

Published in the journal: Čes. slov. Farm., 2015; 64, 36-38

Category: Rozšířená abstrakta z konference

Introduction

In this presentation, which is part of my thesis, I describe the status of Jewish pharmacists in pharmacies on the territory of interwar Czechoslovakia and their fate during World War II.

In interwar Czechoslovakia, Jews comprised 2.42% of all citizens which was considerably less than in other Eastern European countries. According to the census of 1930, 362 530 Jews (by faith) lived in Czechoslovakia. The representation of Jewish population in mainstream Czechoslovak society varied geographically. The Carpathian Ruthenia had the highest percentage of Jews by faith (14.4%), followed by Slovakia (4.14%) and Moravia and Silesia (1.16%). Bohemia had the lowest ratio of Jews in mainstream Czechoslovak society (1.07%) (Kolektiv. Statistická ročenka Republiky československé, 1938)1).

The first Jewish students entered pharmacy studies at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague by the end of the seventies of the nineteenth century. From 1867 to 1918, only a few Jewish students registered each academic year. Elsa Fantová was the first Jewish woman who completed her studies of pharmacy in 1908 in the German part of the University. After creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, students from Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia came to Prague to study pharmacy (the newly established state did not recognize foreign professional qualifications). The number of Jewish students had grown and each academic year dozens of them completed their studies.

Methods

In my work, I intended to identify Jewish pharmacists (by nationality or faith) working in pharmacies on the territory of interwar Czechoslovak Republic. I have been using the following two primary sources of information:

- Catalogues of students of the Czech and the German university in Prague (1882–1938). Catalogues of students of the Charles University in Prague (i.e. the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague) for the period of 1882–1939 and catalogues of students of the German University in Prague (i.e. the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague and the German Charles University in Prague) for the period of 1882–1945 are currently available. These are the official registration books where students enrolled at the beginning of each semester were registered. The records are put in alphabetical order. Regular students comprised the vast majority of students while irregular students were rather an exception. The records in the aforementioned official registration books, such as names, surnames, religion, mother tongue (implemented since 1925), nationality (since 1925), dates of birth, home communities, country of origin, and father’s name and occupation (in case of students from Czechoslovakia), have been very important for my research. I have organized all data in tables.

- The second category of important sources consists of The Pharmacy Yearbook for the Year 1936 (Czech version: Lékárnická ročenka na rok 1936; German version: Apotheken – Zeitweiser 1936: Pharmazeutische Gesetzgebung in der Tschechoslowak Republik 1934–1935) (Kolektiv, 1936)2) and Czechoslovak Health Statistics Yearbook for the year 1938 (Zdravotnická ročenka československá 1938) (Říha, 1938)3).

These books contained address list of pharmacies, the names of their owners, the names of leading pharmacists (“provisor”) and employed pharmacists („kondicinující farmaceut“) from all around the country. The Jews enjoyed equal rights with the rest of Czechoslovak citizens and therefore held various positions in pharmacies. Some of them owned a pharmacy, others managed it for the owners (“provisor”) or worked as employed pharmacists („kondicinující farmaceut“) (Vašatová, B. 2014)4). I have compared the aforementioned lists to tables of pharmacy students and discovered 444 identical names among students and pharmacists in yearbooks.

In addition, I have been using the database of the Holocaust victims and a number of other internet sources (www.holocaust.cz) (Kolektiv. Oběti ghetta Terezín a oběti deportované z českých zemí do ghett Łódź, Minsk a do pracovního tábora Ujazdów, 2014)5) (Kolektiv. Holocaust. cz – Databáze obětí, 2011)6).

Results and discussion

1. The total number of Jewish students of pharmacy in the years 1882–1938

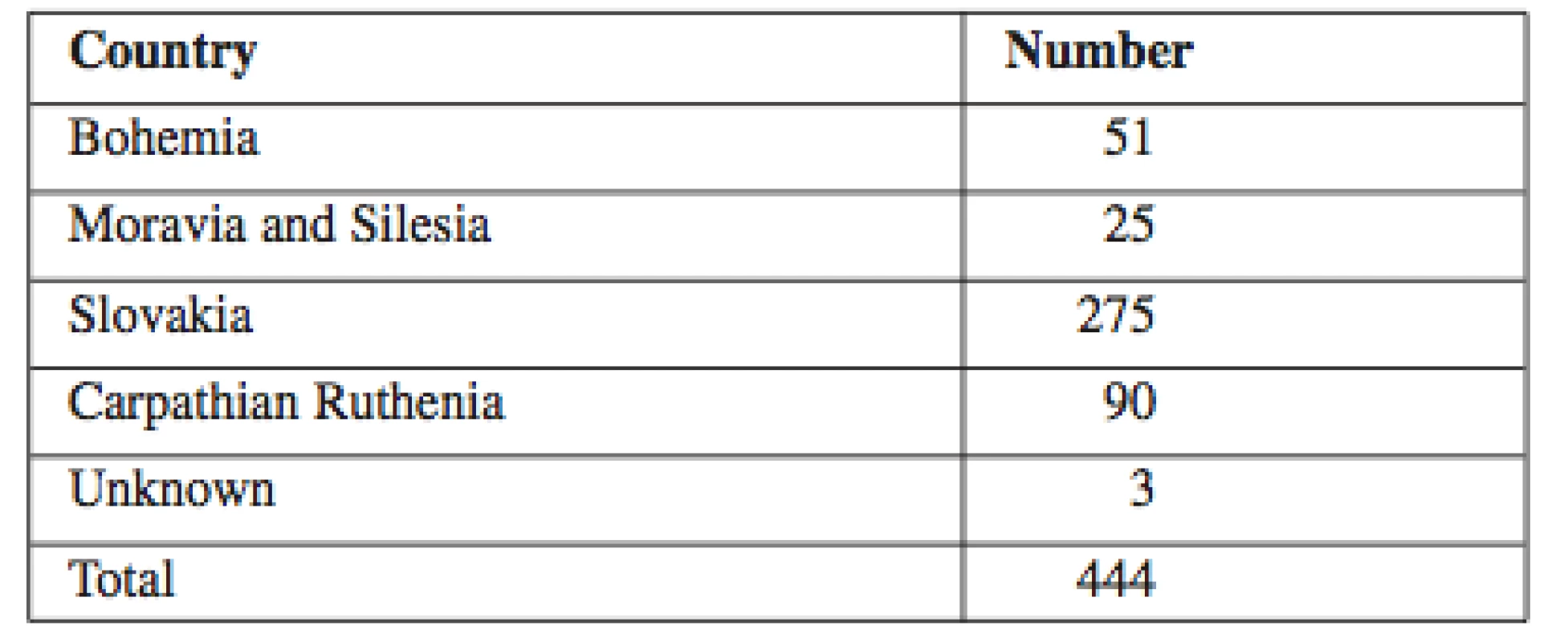

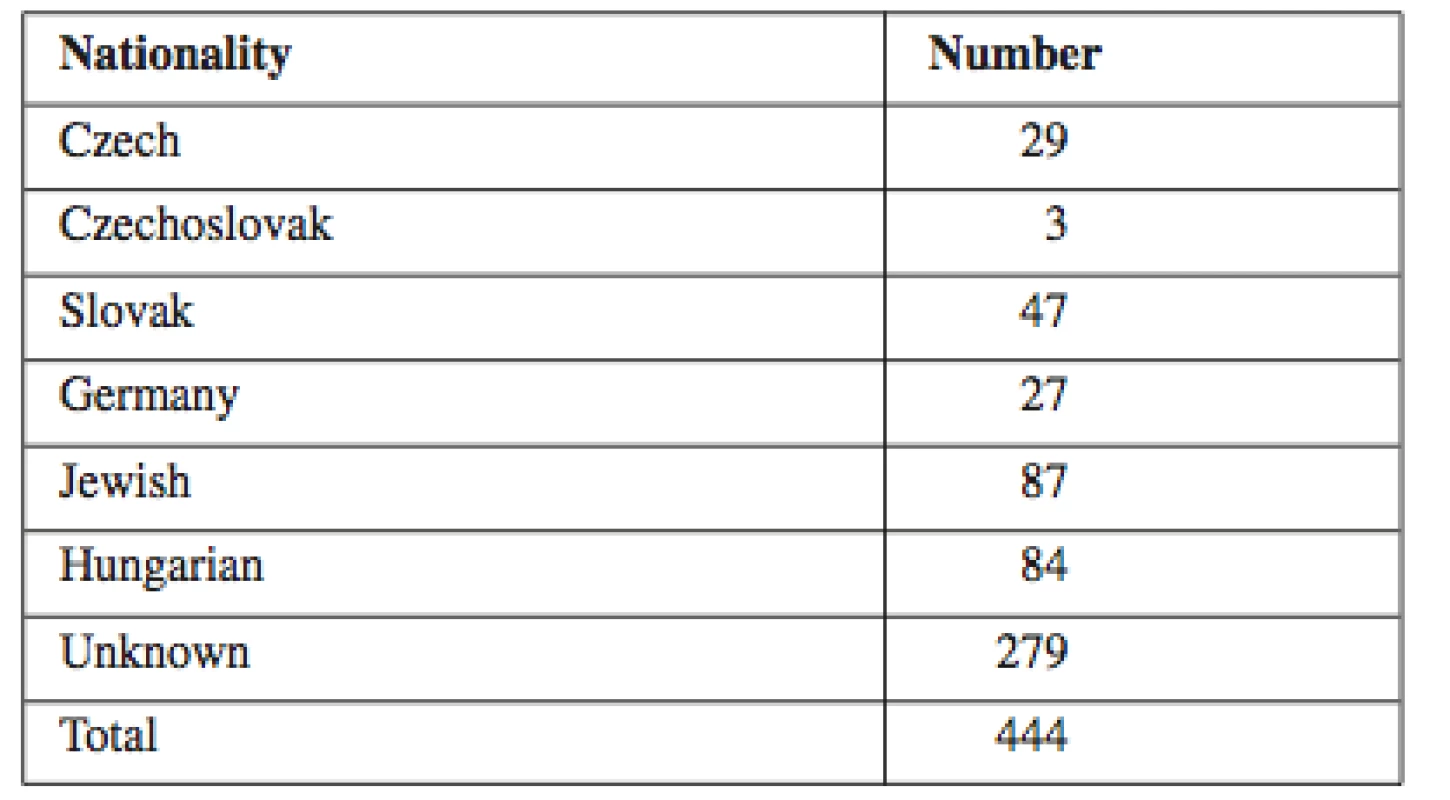

Altogether, 444 students enrolled in the university for at least 1 semester. Most of them either declared Jewish nationality (87) or Slovakia as their home country (275). Out of 444 students, there were 100 women (23%).

Tab. 1. Students by home country

Tab. 2. Students by nationality

2. Students enrolled in the full 4-semestrial program

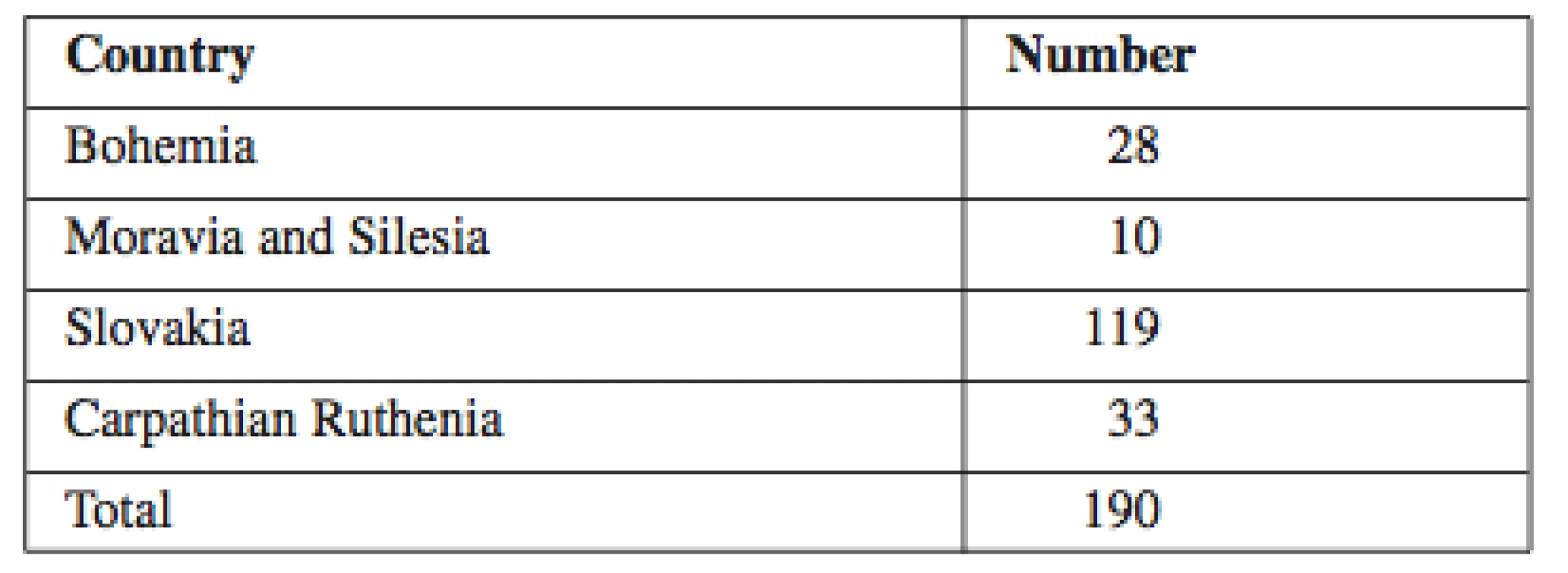

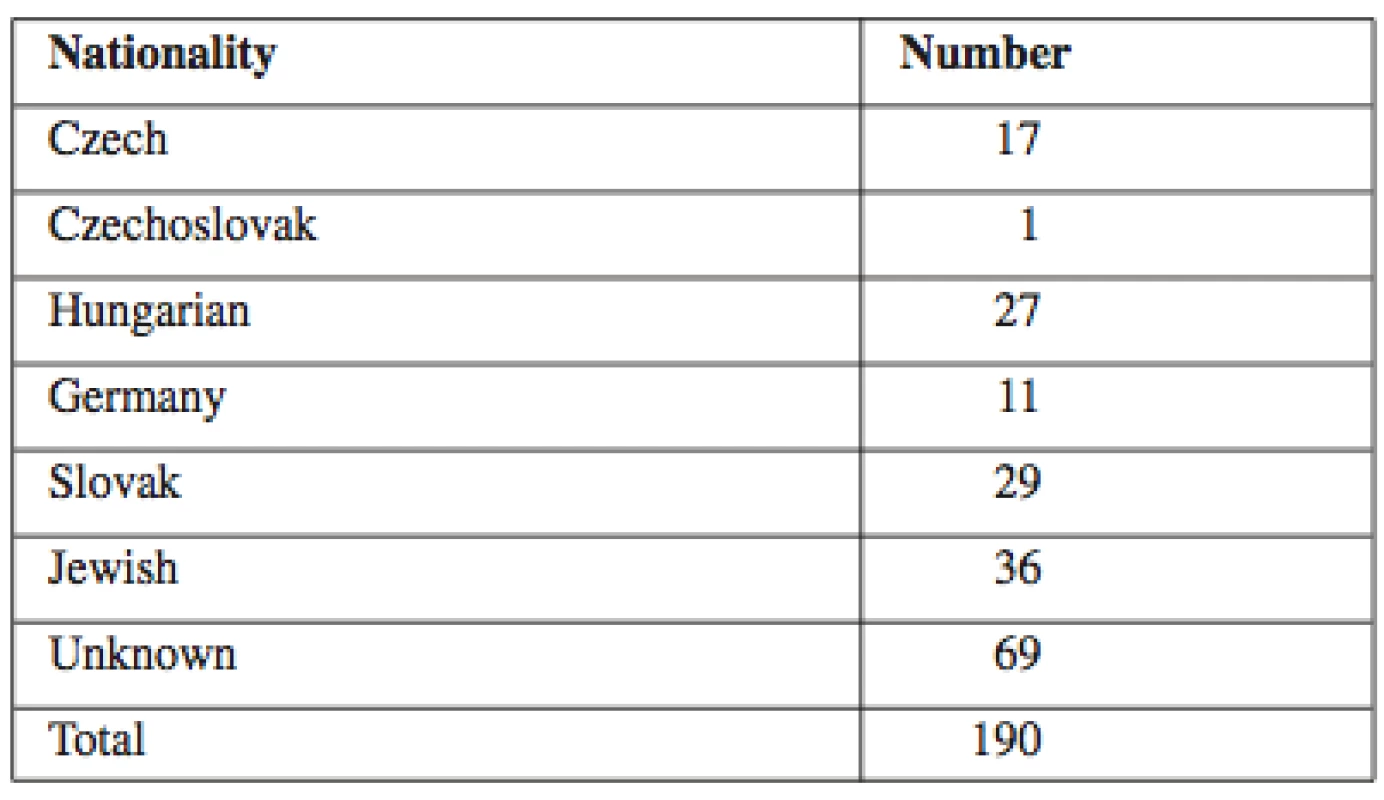

190 students (43%) enrolled in the 4-semestrial program. Most of students declared either Jewish nationality (36) or Slovakia as home country (119). Out of 190 students, there were 40 women (26%).

Tab. 3. Students by home country

Tab. 4. Students by nationality

3. The total number of Jewish pharmacists in pharmacies

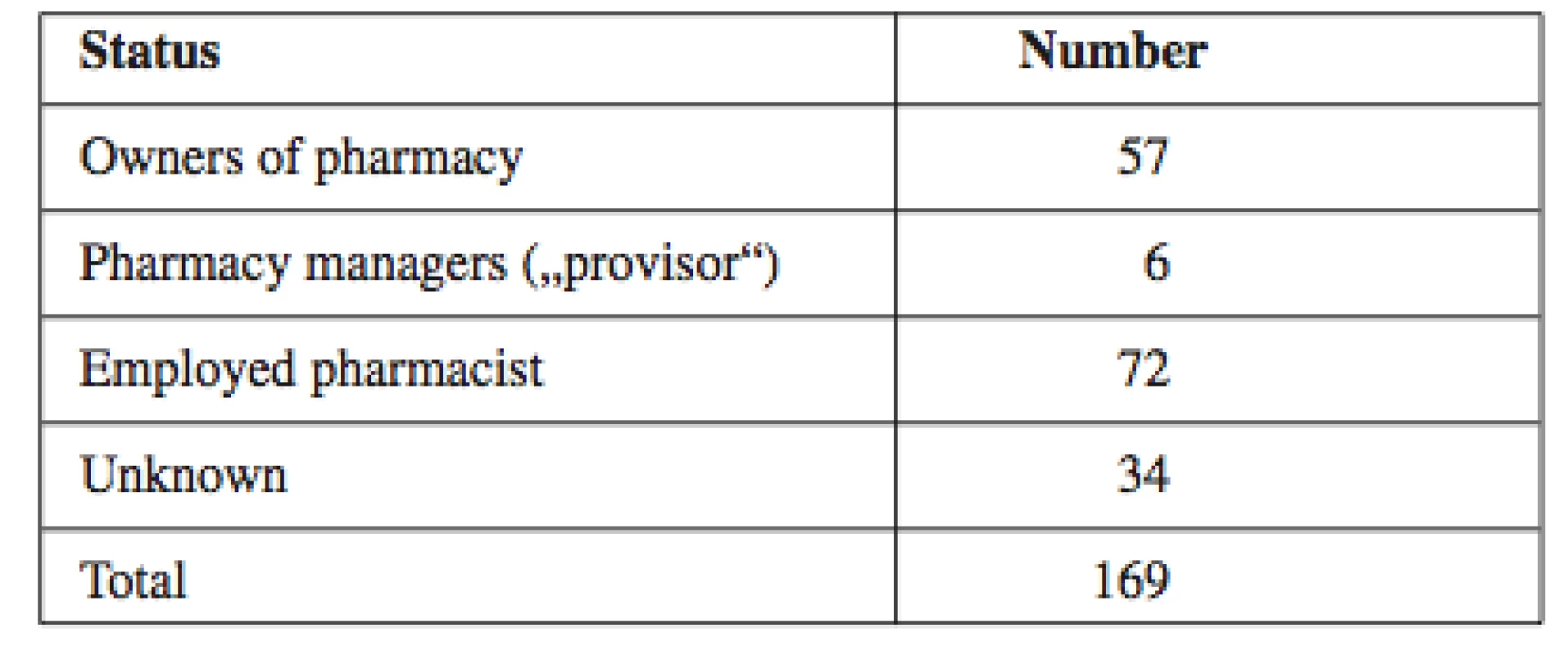

I have compared between the names of students from catalogues and names reported in yearbooks. The list I added the names of Jewish pharmacists from transports to Terezín. (Kolektiv, Oběti ghetta Terezín a oběti deportované z českých zemí do ghett Łódź, Minsk a do pracovního tábora Ujazdów, 2014)5) and from other historical sources (Kolektiv. Holocaust. cz – Databáze obětí, 2011)6). I received 167 names; 57 of them were owners of pharmacies, 6 pharmacy managers, 71 employed pharmacists and 34 with no identified status.

Tab. 5. Pharmacists according to the status in employment

4. Jewish owners of pharmacies

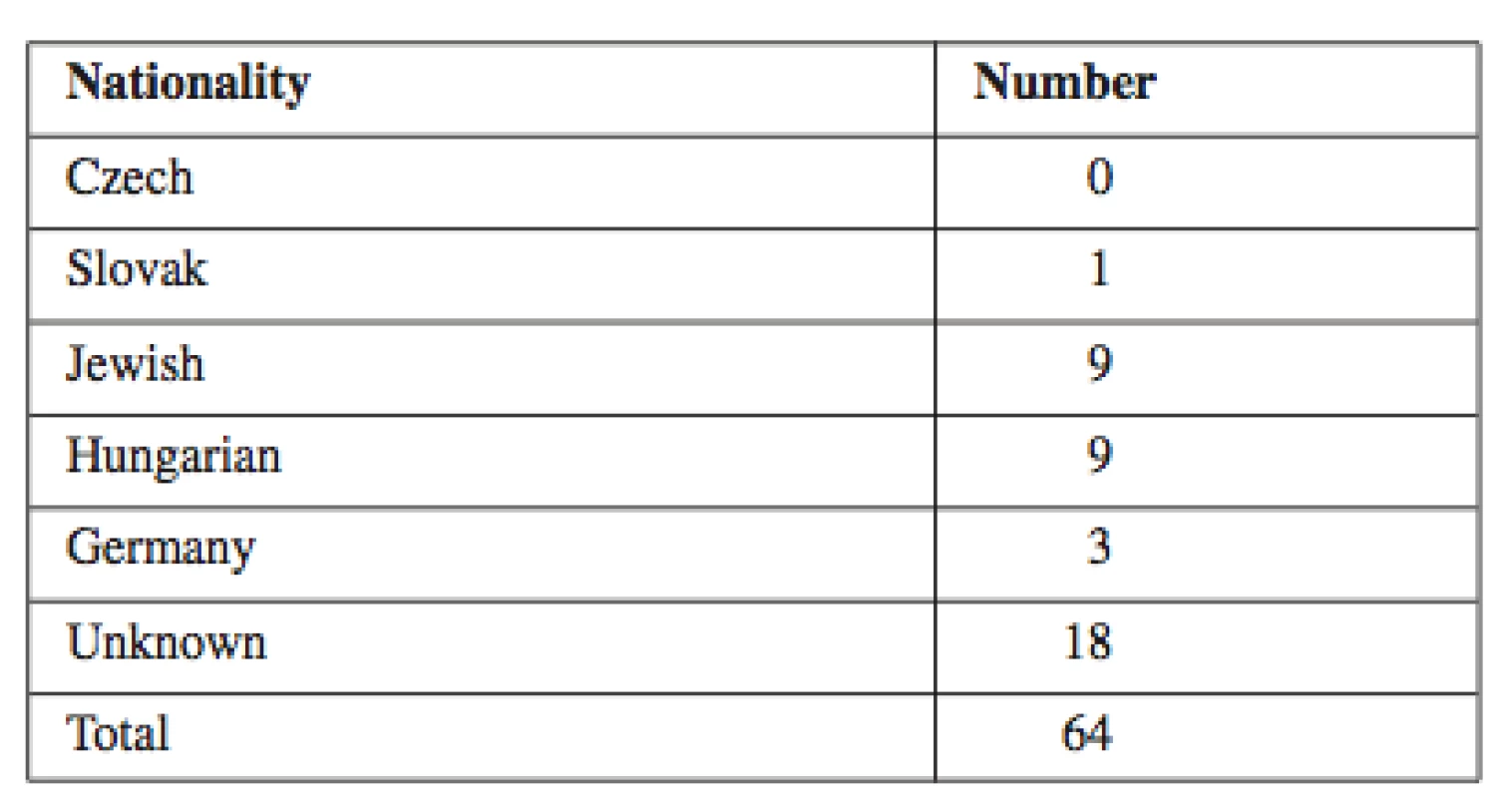

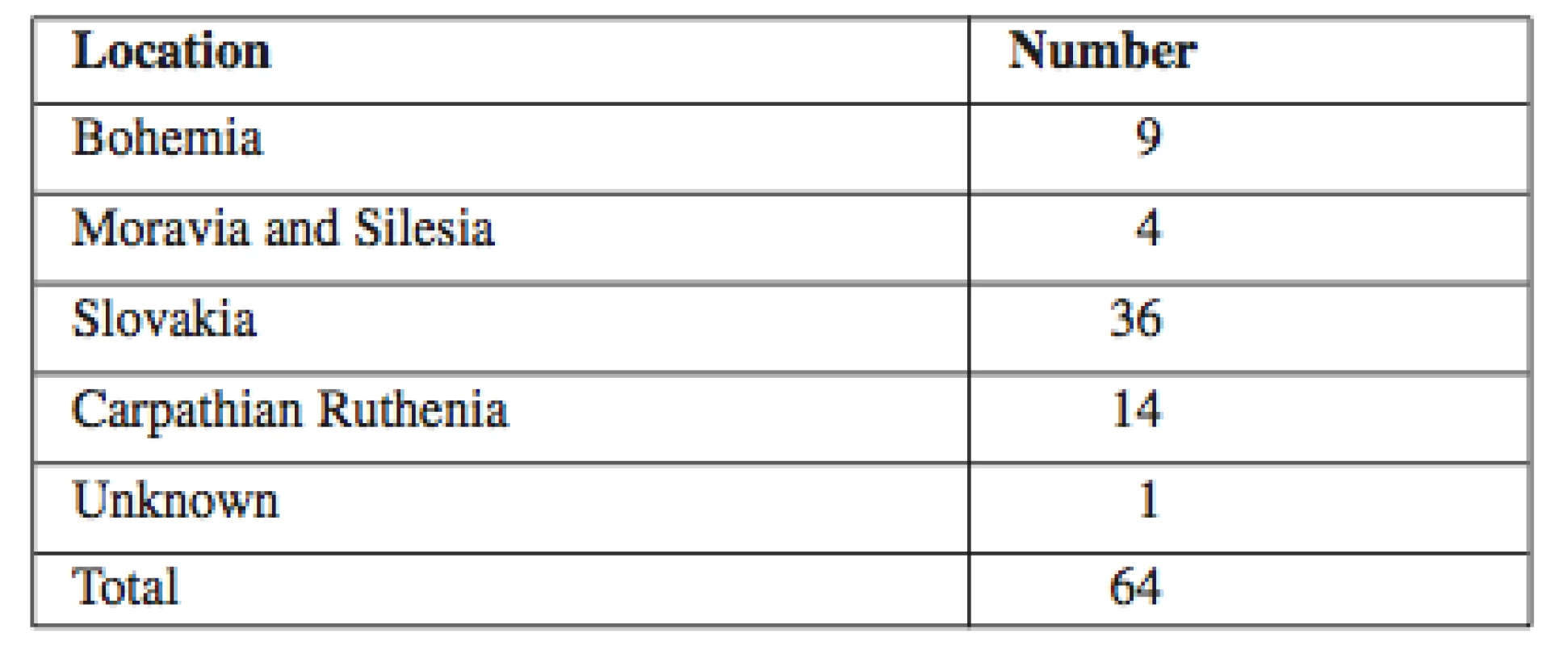

Jewish pharmacists owned most pharmacies in the Slovak Republic (36). Many owners declared their nationality as Jewish (9) and Hungarian (9). Out of 64 pharmacists, there were 3 women (5%).

Tab. 6. Pharmacy owners (and pharmacy managers) by nationality

Tab. 7. Pharmacy owners (and pharmacy managers) by location of pharmacy

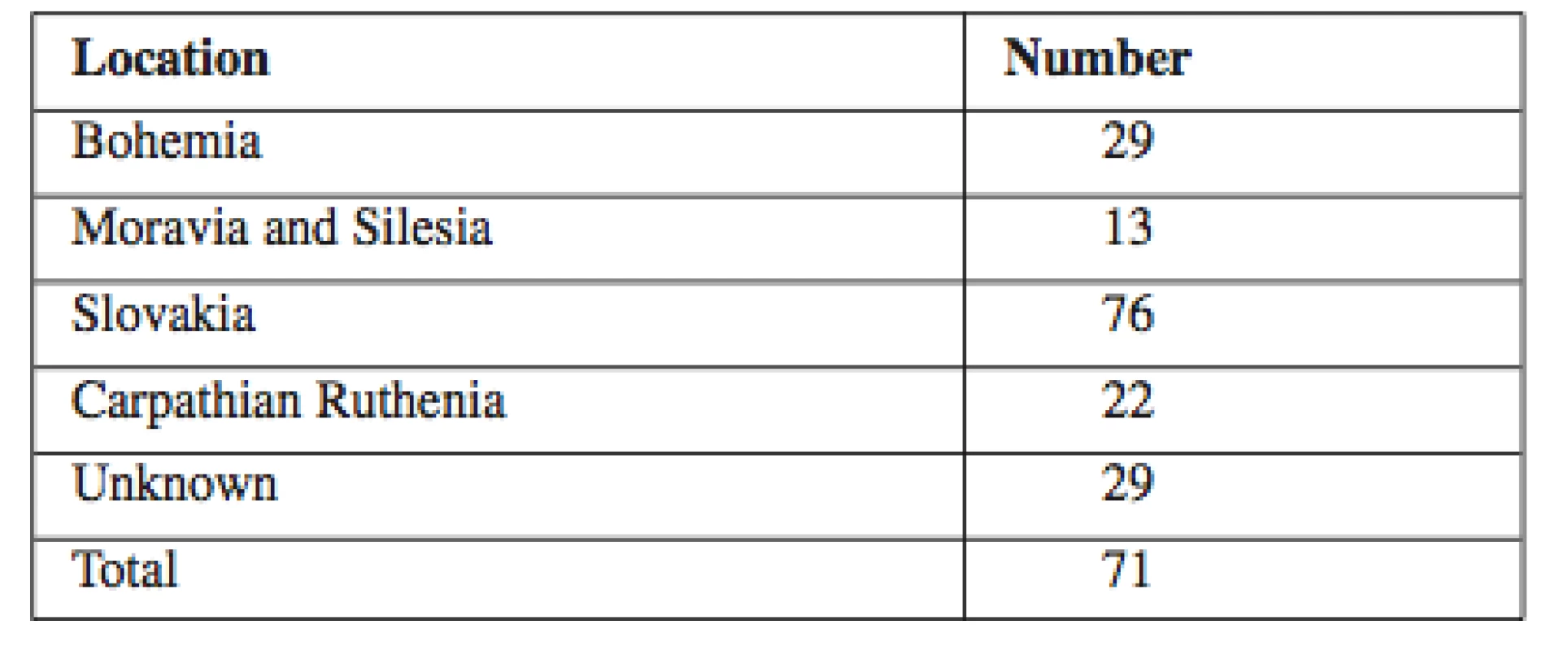

5. Jewish employed pharmacists

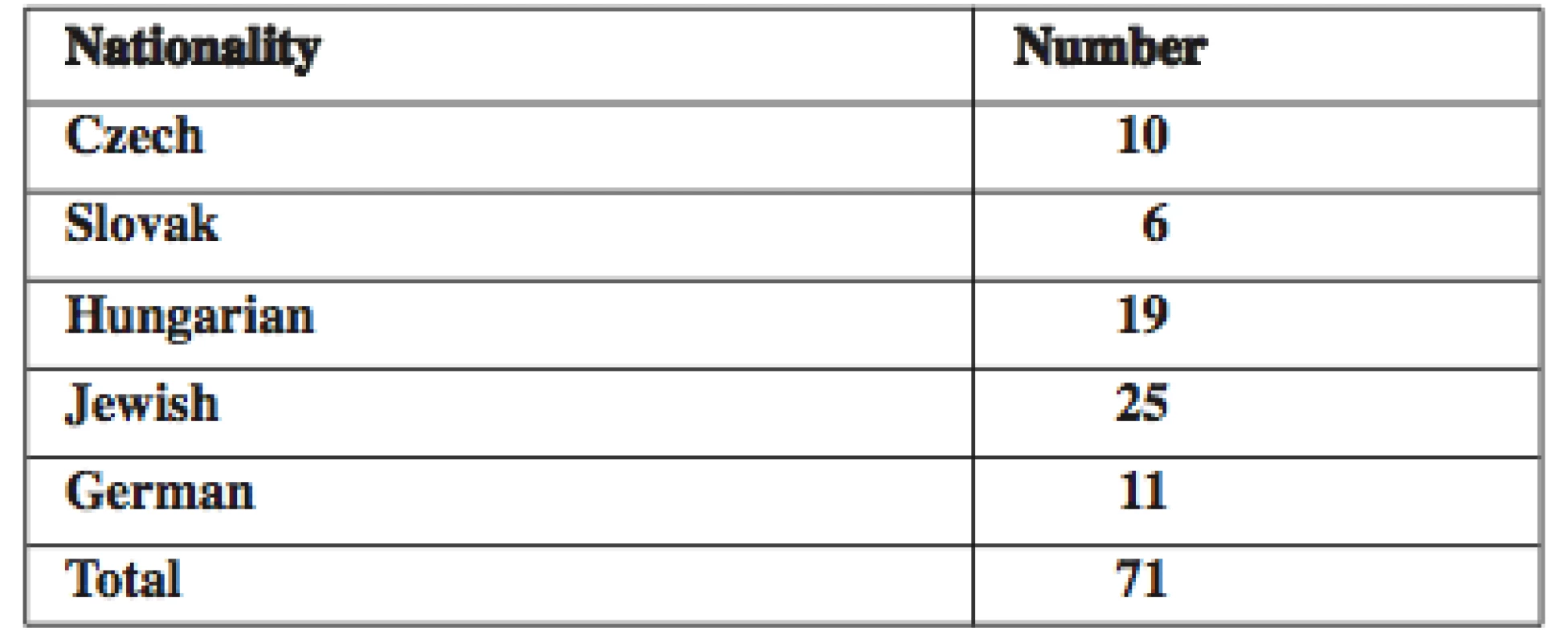

Most employed pharmacists either declared a Jewish nationality (15) or worked in a pharmacy in Slovakia (38). Out of 72 employed pharmacists, 23 were women (32%).

Tab. 8. Employed pharmacists by nationality

Tab. 9. Employed pharmacists by the location of pharmacy

Discussion

The collected data shows a higher percentage of Jewish pharmacists from Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia than from Czech lands. These findings support a previously mentioned fact that the representation of Jewish population in mainstream Czechoslovak society varied geographically. The Carpathian Ruthenia had the highest representation of Jews by faith among its population (14.4%), followed by Slovakia (4.14%) and Moravia and Silesia (1.16%). The smallest number of Jews by faith (1.07%) lived in Bohemia. A higher representation of Jewish pharmacists from Carpathian Ruthenia (compared to Slovakia) expressed the need to improve the level of education in Carpathian Ruthenian district.

After 1918, Prague University became the only place to study pharmaceutics in Czechoslovakia. This increased the number of students from Carpathian Ruthenia and especially from Slovakia in Prague. The number of women among the owners of pharmacies was still very low; however, it was common at that time. On the contrary, the percentage of women among employed pharmacists was higher than among students. I didn’t find any owner of the pharmacy of Czech, Slovak, or the Czechoslovak nationality.

Conclusion

The Munich Agreement, the Second Czechoslovak Republic and the beginning of World War II was a tragedy for Jewish pharmacists. Only a few managed to emigrate in time (e.g. PhMr. R. Teichmann and Phmr. E. Wollisch from Carlsbad) (Vaňková, 2012)7). Most of those who remained were deported to ghetto Terezín and worked in the pharmacy there. Some of them died in the ghetto, others lost their lives in concentration camps (such as Dachau or Auschwitz). Up to now, I found 48 names of Jewish pharmacists from the Czech lands transported to ghetto Terezín. Most of them were murdered in Auschwitz (17), Treblinka (4) and some died in ghetto Łódź (5). Six pharmacists survived the war in ghetto Terezín and remained there until its liberation by the Red Army on May 8, 1945.

The story of the Slovakian Jews (including occupied Carpathian Ruthenia and south of Slovakia) was to some extend different however no less tragic. Their fate will be further explored in my dissertation.

This article was supported by grant SVV 260 066.

Conflicts of interest: none.

ARNDT T.

Department of Social and Clinical Pharmacy of Faculty of Pharmacy in Hradec Králové, Charles University in Czech Republic

e-mail: arndttomas66@gmail.com

Zdroje

1. Říha, J. Zdravotnická ročenka československá (sv. 10). Praha: Nakladatelství Piras 1938.

2. Kolektiv. Statistická ročenka Republiky československé (sv. 9). Praha: Nakladatelství Orbis 1938.

3. Kollektiv. Apotheken-Zeitweiser ...: pharmazeutische Gesetzbung in der tschechosl. Republik ...: Handbuch des Verbandes deutscher Apotheker in der tschechosl. Republik. Marienbad: Verlag Sudetendeutsche Apotheke-Zeitung 1936.

4. Vašatová, B. Farmacie v Českých zemích 1938/1939–1945 (diplomová práce). Hradec Králové: Farmaceutická fakulta Univerzity Karlovy 2014.

5. Kolektiv. Holocaust.cz – Databáze obětí. http://www.holocaust.cz/ databaze-obeti, 30.11.2011.

6. Kolektiv. Oběti ghetta Terezín a oběti deportované z českých zemí do ghett Łódź, Minsk a do pracovního tábora Ujazdów. Databáze Památníku Terezín: http://www.pamatnik-terezin.cz/vyhledavani/ ghetto, 24.9.2014.

7. Vaňková, J. Dějiny lékárenství v Karlových Varech (diplomová práce). Hradec Králové: Farmaceutická fakulta Univerzity Karlovy 2012.

Štítky

Farmacie Farmakologie

Článek vyšel v časopiseČeská a slovenská farmacie

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 1-2- Psilocybin je v Česku od 1. ledna 2026 schválený. Co to znamená v praxi?

- Ukažte mi, jak kašlete, a já vám řeknu, co vám je

- FDA varuje před selfmonitoringem cukru pomocí chytrých hodinek. Jak je to v Česku?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Vliv velikosti otvoru kónické testovací násypky na parametry rovnice sypání sorbitolu a jeho velikostních frakcí

- Příprava a hodnocení 5-amino-N-fenylpyrazin-2-karboxamidů jako potenciálních antiinfektiv

- Alzheimerova nemoc: význam nových léků a národní strategie pro snížení nákladů na léčbu

- Účinnost fytoterapie v podpůrné léčbě diabetes mellitus typu 2 Borůvka černá (Vaccinium myrtillus)

- Užívání vybraných OTC přípravků: srovnání Řecko a Česká republika

- 5. postgradual and 3. postdoctoral conference Faculty of Pharmacy UK

- Jewish pharmacists in pharmacies of interwar Czechoslovakia and their lives during World War II

- Computational approach to search for novel antituberculostics

- Alkaloids from hydrastidis canadensis and their cholinesterase and prolyl oligopeptidase inhibitory

- K životnému jubileu pani doc. RNDr. Zuzany Vitkovej, PhD.

- Podpora aktivní účasti jednoho člena České farmaceutické společnosti na kongresu FIP v Düsseldorfu

- Výskum a vývoj liekových foriem v súčasnosti

- Zdravotnícke pomôcky. Legislatíva a regulácia.

- Alois Borovanský, farmaceutický chemik par excellence

- Jedová stopa.

- Antitrombotiká v klinickej praxi.

- Biologická dostupnost léčiva a možnosti jejího ovlivňování

- Česká a slovenská farmacie

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Biologická dostupnost léčiva a možnosti jejího ovlivňování

- Účinnost fytoterapie v podpůrné léčbě diabetes mellitus typu 2 Borůvka černá (Vaccinium myrtillus)

- Užívání vybraných OTC přípravků: srovnání Řecko a Česká republika

- Jedová stopa.

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání