-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaGenomic Insights into the Fungal Pathogens of the Genus : Obligate Biotrophs of Humans and Other Mammals

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004425

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004425Summary

article has not abstract

Pneumocystis organisms were first believed to be a single protozoan species able to colonize the lungs of all mammals. Subsequently, genetic analyses revealed their affiliation to the fungal Taphrinomycotina subphylum of the Ascomycota, a clade which encompasses plant pathogens and free-living yeasts. It also appeared that, despite their similar morphological appearance, these fungi constitute a family of relatively divergent species, each with a strict specificity for a unique mammalian species [1]. The species colonizing human lungs, Pneumocystis jirovecii, can turn into an opportunistic pathogen that causes Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in immunocompromised individuals, a disease which may be fatal. Although the incidence of PCP diminished in the 1990s thanks to prophylaxis and antiretroviral therapy, PCP is nowadays the second-most-frequent, life-threatening, invasive fungal infection worldwide, with an estimated number of cases per year above 400,000 [2]. Despite this clinical importance, studies of P. jirovecii progressed slowly, at least in part because of the lack of a continuous culture system. Nevertheless, recent genomic findings provided insights into the lifestyle of these fungi.

Genome Sequences

Despite the absence of culture, the nuclear genome sequences of three Pneumocystis spp. have been recently released to the public. That of P. carinii, the species infecting rats, was obtained from resected lungs of an infected rat and purification of P. carinii cells (pgp.cchmc.org). This provided sufficient amounts of relatively pure DNA for conventional cloning and sequencing of chromosomes separated on gel, as well as for high throughput DNA sequencings (HTS). The nuclear genome sequence of P. murina, the species infecting mice, was obtained from resected lungs followed by HTS (Pneumocystis murina Sequencing Project, Broad Institute of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, http://www.broadinstitute.org/). Thanks to cell immunoprecipitation and whole genome amplification, the P. jirovecii nuclear genome sequence was obtained using HTS from a single bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample of a single patient with PCP [3]. Because of the low DNA purity, the assembly necessitated an innovative approach using iterative identification of the fungal homologies among the reads from the host and lung microbiota. The genome sequences of the mitochondria were also obtained from the same sequencings, as well as by PCR [4], [5].

Genomic Assemblies

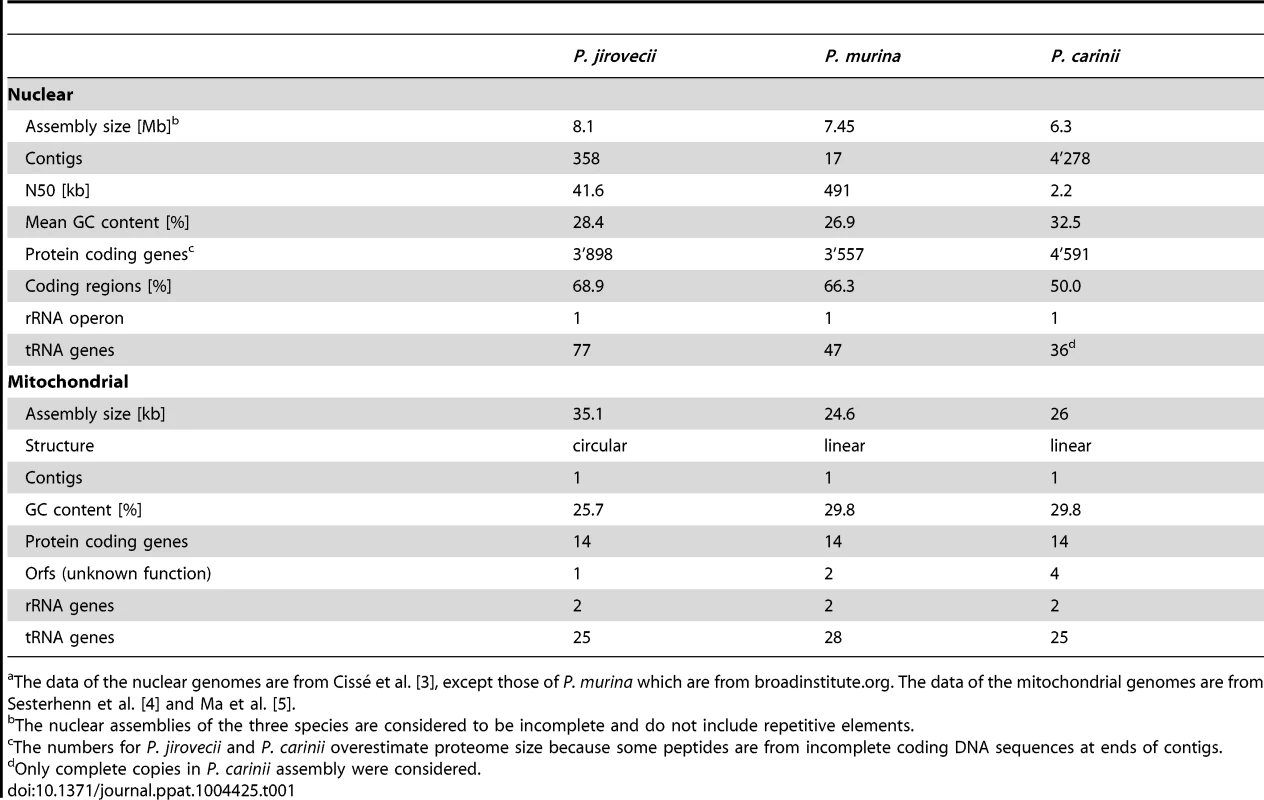

The nuclear genome assembly of P. carinii is still highly fragmented, whereas that of P. murina is made of 17 contigs likely to correspond to the 17 chromosomes composing this genome (Table 1). The P. jirovecii nuclear assembly presents an intermediary fragmentation, which results from the difficulty of assembling it out of a mixture of reads. Because of their repetitive nature, telomeres were not assembled. The nuclear genomes of the three Pneumocystis spp. are approximately 8 Mb.

Tab. 1. Statistics of Pneumocystis spp. nuclear and mitochondrial genomic assembliesa.

The data of the nuclear genomes are from Cissé et al. [3], except those of P. murina which are from broadinstitute.org. The data of the mitochondrial genomes are from Sesterhenn et al. [4] and Ma et al. [5]. The mitochondrial genomes of P. murina and P. carinii are approximately 25 kb, whereas that of P. jirovecii is around 35 kb (Table 1). This size difference is due to a supplementary region that is non-coding and highly variable in size and sequence among isolates [5]. The circular structure of the P. jirovecii mitochondrial genome differs from the linear one present in the two other Pneumocystis spp. The biological significance of this difference remains unknown.

Genome Content

Using gene models specifically developed, the three Pneumocystis spp. nuclear genomes were predicted to encode approximately 3,600 protein coding genes (Table 1). Mapping of the genes onto the chromosomes is achieved for P. murina because contigs correspond to chromosomes, as well as for P. carinii because isolated chromosomes were sequenced, but not for P. jirovecii. Functional annotation was optimized by the use of transcription data as well as of carefully chosen fungal proteomes as intermediary data for mapping onto the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) atlas of biochemical pathways [3], [6]. About 30%–40% of the genes were reported to encode hypothetical proteins without significant homology with the databases, but this proportion is decreasing as new fungal genome sequences are released. A maximum likelihood phylogeny from the alignment of 458 concatenated orthologs revealed Taphrina deformans and the members of the Schizosaccharomyces genus as the closest relatives of Pneumocystis spp. [3], [7]. The genome content of the three Pneumocystis spp. covered most of the biochemical pathways corresponding to the basal metabolism and standard cellular processes [6], [8]. Specific features included the presence of a single operon encoding the ribosomal RNA (Table 1), such as T. deformans [7], which contrasts with the tens or hundreds in other fungi, and the lack of common fungal virulence factors such as the glyoxylate cycle and polyketide synthase clusters [3], [6], [8]. The mitochondrial genomes of the three Pneumocystis spp. encode 15 to 17 proteins (Table 1).

Genomic Insights by Comparative Genomics

Relevant features of the P. carinii genome were compared to those of the free-living yeast S. cerevisiae and of the extreme fungal obligate parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi [9]. Intermediate values of gene number, genome size, and mean intergenic space suggested that P. carinii might be in the process of becoming dependent on its host. The use of Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome sequence as a control for genomic annotation revealed the absence of most of the enzymes specifically dedicated to the synthesis of amino acids in Pneumocystis spp. [3], [6]. Whole genome comparison to other representatives of the Taphrinomycotina subphylum revealed several supplementary gene losses in P. carinii and P. jirovecii (P. murina could not be analyzed because its genome sequence was released prior to publication under specific terms). The hypothetical gene repertoires of ancestors were reconstructed using maximum parsimony and the irreversible Dollo model of evolution [10]. The approach identified approximately 2,000 genes presumably lost by the common ancestor of Pneumocystis and Taphrina genera during its evolution towards the Pneumocystis genus. Analysis of these genes revealed losses of genes that impair the biosynthesis of thiamine, the assimilation of inorganic nitrogen and sulfur, and the catabolism of purines. In addition, lytic proteases, which are believed to be crucial to fungal virulence, were underrepresented. The absence of the genes was ascertained by extensive gene searches in partially overlapping data sets expected to cover 100% of the genomes, and by the fact that it was observed in both P. carinii and P. jirovecii. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that we cannot firmly exclude the presence of genes of a previously unknown origin that have not been observed in other organisms so far, and thus would be undetectable because they are absent from the databases. These gene losses constitute an important signature of the lifestyle of Pneumocystis spp.

Obligate Parasitism

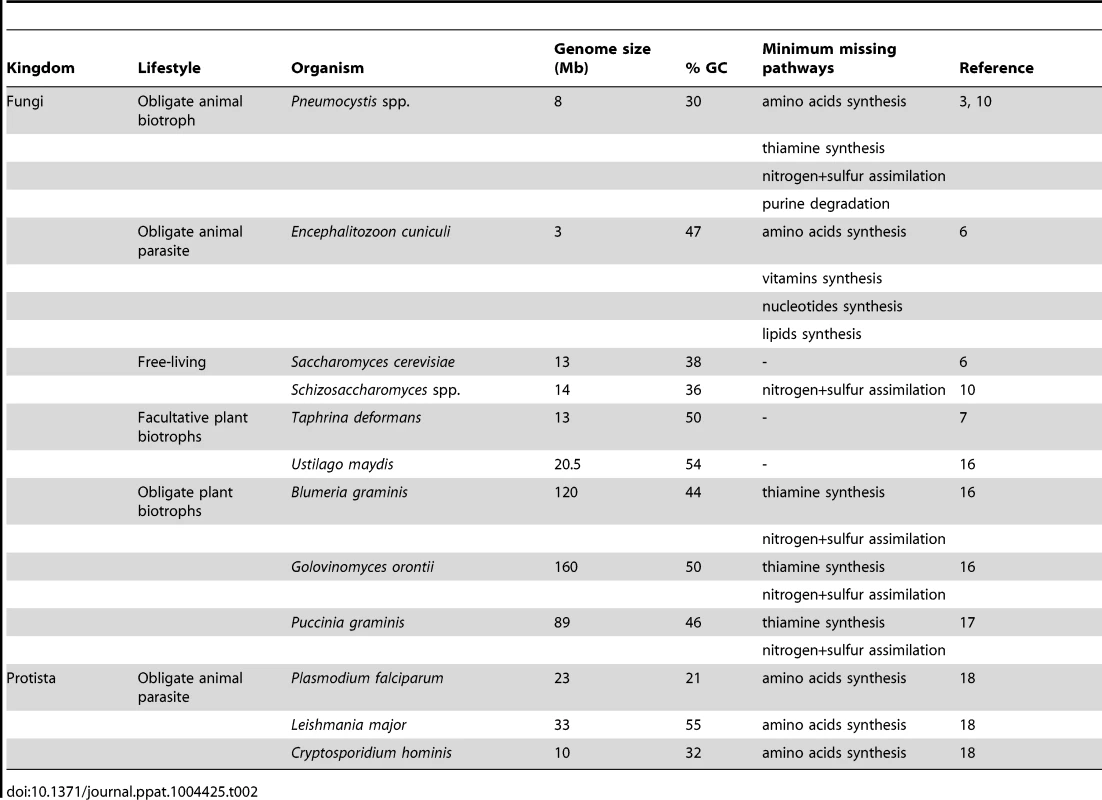

The loss of biosynthetic pathways of essential molecules is a hallmark of obligate parasitism in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms [11], [12]. These losses are believed to be allowed by the availability of the end products of the pathways within the host environment. Similarly, the absence of substrate may explain the loss of assimilation pathways. The loss of amino acids and thiamine biosyntheses in Pneumocystis spp. strongly suggests that they are obligate parasites. Thus, their entire cycle probably takes place within the host lungs, and no free-living form of these fungi would exist. In addition to amino acids and thiamine, Pneumocystis spp. are believed to scavenge cholesterol from their host to build their own membranes [13]. In bacteria, gene losses associated with obligate parasitism imply a reduction of the genome size linked to a reduction of the guanine-cytosine (GC) content [14]. Likewise, Pneumocystis spp. genomes have smaller genome size and GC content than their free-living and facultative parasite relatives, respectively Schizosaccharomyces spp. and T. deformans (Table 2).

Tab. 2. Some features of selected microorganisms with various lifestyles.

Biotrophy

Two categories of parasites are recognized: biotrophs, which secrete low amounts of lytic enzymes and obtain food from living host cells, and necrotrophs, which secrete many degrading enzymes and toxins and obtain food from dead host cells [15]. The missing pathways of Pneumocystis spp. are shown in Table 2 together with those of selected microorganisms with various lifestyles. The requirement in thiamine and the absence of inorganic nitrogen and sulfur assimilation are hallmarks of obligate plant biotrophs [16]. Several other biological characteristics of Pneumocystis spp. are also hallmarks of obligate biotrophs: (i) the absence of destruction of host cells during colonization as well as during pathogenic infection, (ii) the lack of known virulence factors, (iii) a sex life cycle occurring within the host, and (iv) the difficulty to be cultured in vitro so far [8], [16], [17]. On the other hand, the loss of the catabolism of purines and of the amino acids syntheses revealed in Pneumocystis spp. has not been observed in fungal biotrophs so far. The first loss might be specific to Pneumocystis spp., but the second is a hallmark of organisms feeding on other animals, such as obligate parasites of humans [18] (Table 2). This latter loss might be related to the adaptation to animal hosts and suggests that there are more proteins available in animal than plant hosts. Thus, the genomic and biological characteristics of Pneumocystis spp. suggest the working hypothesis that they are obligate biotrophic parasites of mammals. This hypothesis has been already proposed previously on the basis of the analysis of P. carinii transcriptome [8], as well as of the biological characteristics of Pneumocystis spp. [1]. Experiments are required in order to test this hypothesis. In particular, the computational predictions supporting obligate biotrophy need to be verified. Pneumocystis spp. would be the first fungal biotrophs of animals recognized so far. Of note, the lifestyle of P. jirovecii differs from the other fungal obligate parasites of humans, Malassezia and Candida spp., which are obligate commensals and opportunistic necrotrophs.

The reduction of genome size in Pneumocystis spp. contrasts with the increase of this parameter in some fungal obligate plant biotrophs (Table 2). This latter increase corresponds to a proliferation of retrotransposons, which may create genetic variability and diversity including panels of effectors involved in virulence [16]. As in Ustilago maydis (Table 2), the genome size reduction in Pneumocystis spp. might be compensated by the genetic diversity generated by sexuality, suggesting that they might be obligate sexual organisms. This hypothesis would fit the fact that the asci issued from the sexual cycle might be the unique airborne particles responsible for the transmission of the fungus [19].

Epidemiological Consequence

Obligate parasitism of P. jirovecii has important implications in the management of immunocompromised patients susceptible to PCP. Indeed, the fungus is most probably restricted to the lungs of humans so that the only sources of the infection are patients with PCP and colonized humans, such as infants experiencing primo-infection and transitory carriers, as well as, possibly, pregnant women and elderly people [20].

Zdroje

1. CushionMT, StringerJR (2010) Stealth and opportunism: alternative lifestyles of species in the fungal genus Pneumocystis. Annu Rev Microbiol 64 : 431–452.

2. BrownGD, DenningDW, GowNAR, LevitzSM, NeteaMG, et al. (2012) Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4 : 165rv13.

3. CisséOH, PagniM, HauserPM (2012) De novo assembly of the Pneumocystis jirovecii genome from a single bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimen from a patient. MBio 4: e00428–00412.

4. SesterhennTM, SlavenBE, KeelySP, SmulianAG, LangBF, et al. (2010) Sequence and structure of the linear mitochondrial genome of Pneumocystis carinii. Mol Genet Genomics 283 : 63–72.

5. MaL, HuangDW, CuomoCA, SykesS, FantoniG, et al. (2013) Sequencing and characterization of the complete mitochondrial genomes of three Pneumocystis species provide new insights into divergence between human and rodent Pneumocystis. FASEB J 27 : 1962–1972.

6. HauserPM, BurdetFX, CisséOH, KellerL, TafféP, et al. (2010) Comparative genomics suggests that the fungal pathogen Pneumocystis is an obligate parasite scavenging amino acids from its host's lungs. PLoS ONE 5: e15152.

7. CisséOH, AlmeidaJM, FonsecaA, KumarAA, SalojärviJ, et al. (2013) Genome sequencing of the plant pathogen Taphrina deformans, the causal agent of peach leaf curl. MBio 4: e00055–00013.

8. CushionMT, SmulianAG, SlavenBE, SesterhennT, ArnoldJ, et al. (2007) Transcriptome of Pneumocystis carinii during fulminate infection: carbohydrate metabolism and the concept of a compatible parasite. PLoS ONE 2: e423.

9. CushionMT (2004) Comparative genomics of Pneumocystis carinii with other protists: implications for life style. J Eukaryot Microbiol 51 : 30–37.

10. CisséOH, PagniM, HauserPM (2014) Comparative genomics suggests that the human pathogenic fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii acquired obligate biotrophy through gene loss. Genome Biol Evol 6 In Press.

11. AnderssonJO, AnderssonSG (1999) Insights into the evolutionary process of genome degradation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 9 : 664–671.

12. SakharkarKR, DharPK, ChowVT (2004) Genome reduction in prokaryotic obligatory intracellular parasites of humans: a comparative analysis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54 : 1937–1941.

13. JoffrionTM, CushionMT (2010) Sterol biosynthesis and sterol uptake in the fungal pathogen Pneumocystis carinii. FEMS Microbiol Lett 311 : 1–9.

14. MerhejV, Royer-CarenziM, PontarottiP, RaoultD (2009) Massive comparative genomic analysis reveals convergent evolution of specialized bacteria. Biol Direct 4 : 13.

15. KemenE, JonesJD (2012) Obligate biotroph parasitism: can we link genomes to lifestyles? Trends Plant Sci 17 : 448–457.

16. SpanuPD (2012) The genomics of obligate (and nonobligate) biotrophs. Annu Rev Phytopathol 50 : 91–109.

17. O'ConnellRJ, PanstrugaR (2006) Tête à tête inside a plant cell: establishing compatibility between plants and biotrophic fungi and oomycetes. New Phytol 171 : 699–718.

18. PayneSH, LoomisWF (2006) Retention and loss of amino acid biosynthetic pathways based on analysis of whole-genome sequences. Eukaryot Cell 5 : 272–276.

19. CushionMT, LinkeMJ, AshbaughA, et al. (2010) Echinocandin treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia in rodent models depletes cysts leaving trophic burdens that cannot transmit the infection. PLoS ONE 5: e8524.

20. MorrisA, NorrisKA (2012) Colonization by Pneumocystis jirovecii and its role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 25 : 297–317.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Acidification Activates Motility and Egress by Enhancing Protein Secretion and Cytolytic ActivityČlánek Plasticity between MyoC- and MyoA-Glideosomes: An Example of Functional Compensation in InvasionČlánek Coronavirus Cell Entry Occurs through the Endo-/Lysosomal Pathway in a Proteolysis-Dependent MannerČlánek NK Cell Activation in Human Hantavirus Infection Explained by Virus-Induced IL-15/IL15Rα Expression

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 11- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Měli bychom postcovidový syndrom léčit antidepresivy?

- Farmakovigilanční studie perorálních antivirotik indikovaných v léčbě COVID-19

- 10 bodů k očkování proti COVID-19: stanovisko České společnosti alergologie a klinické imunologie ČLS JEP

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Peculiarities of Prion Diseases

- Inhibitors of Peptidyl Proline Isomerases As Antivirals in Hepatitis C and Other Viruses

- War and Infectious Diseases: Challenges of the Syrian Civil War

- Microbial Contamination in Next Generation Sequencing: Implications for Sequence-Based Analysis of Clinical Samples

- Acidification Activates Motility and Egress by Enhancing Protein Secretion and Cytolytic Activity

- Co-dependence of HTLV-1 p12 and p8 Functions in Virus Persistence

- Shed GP of Ebola Virus Triggers Immune Activation and Increased Vascular Permeability

- Plasticity between MyoC- and MyoA-Glideosomes: An Example of Functional Compensation in Invasion

- The Type III Translocon Is Required for Biofilm Formation at the Epithelial Barrier

- Retromer Regulates HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Trafficking and Incorporation into Virions

- IFI16 Restricts HSV-1 Replication by Accumulating on the HSV-1 Genome, Repressing HSV-1 Gene Expression, and Directly or Indirectly Modulating Histone Modifications

- Coronavirus Cell Entry Occurs through the Endo-/Lysosomal Pathway in a Proteolysis-Dependent Manner

- Silencing by H-NS Potentiated the Evolution of

- Crystal Structure of Cytomegalovirus IE1 Protein Reveals Targeting of TRIM Family Member PML via Coiled-Coil Interactions

- GAPDH-A Recruits a Plant Virus Movement Protein to Cortical Virus Replication Complexes to Facilitate Viral Cell-to-Cell Movement

- Genomic Insights into the Fungal Pathogens of the Genus : Obligate Biotrophs of Humans and Other Mammals

- Unravelling Human Trypanotolerance: IL8 is Associated with Infection Control whereas IL10 and TNFα Are Associated with Subsequent Disease Development

- The Skin Microbiome: A Focus on Pathogens and Their Association with Skin Disease

- Human Cytomegalovirus Vaccine Based on the Envelope gH/gL Pentamer Complex

- IL-37 Inhibits Inflammasome Activation and Disease Severity in Murine Aspergillosis

- Host-Specific Parvovirus Evolution in Nature Is Recapitulated by Adaptation to Different Carnivore Species

- Activation of HIV Transcription with Short-Course Vorinostat in HIV-Infected Patients on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy

- PUL21a-Cyclin A2 Interaction is Required to Protect Human Cytomegalovirus-Infected Cells from the Deleterious Consequences of Mitotic Entry

- Programmed Ribosomal Frameshift Alters Expression of West Nile Virus Genes and Facilitates Virus Replication in Birds and Mosquitoes

- Aminoterminal Amphipathic α-Helix AH1 of Hepatitis C Virus Nonstructural Protein 4B Possesses a Dual Role in RNA Replication and Virus Production

- NK Cell Activation in Human Hantavirus Infection Explained by Virus-Induced IL-15/IL15Rα Expression

- Structure and Specificity of the Bacterial Cysteine Methyltransferase Effector NleE Suggests a Novel Substrate in Human DNA Repair Pathway

- Genetics, Receptor Binding Property, and Transmissibility in Mammals of Naturally Isolated H9N2 Avian Influenza Viruses

- A Gatekeeper Chaperone Complex Directs Translocator Secretion during Type Three Secretion

- A Conserved Peptide Pattern from a Widespread Microbial Virulence Factor Triggers Pattern-Induced Immunity in

- Succinate Dehydrogenase is the Regulator of Respiration in

- The Plasmodesmal Protein PDLP1 Localises to Haustoria-Associated Membranes during Downy Mildew Infection and Regulates Callose Deposition

- Dysregulated B Cell Expression of RANKL and OPG Correlates with Loss of Bone Mineral Density in HIV Infection

- Restriction of Genetic Diversity during Infection of the Vector Midgut

- The Epithelial αvβ3-Integrin Boosts the MYD88-Dependent TLR2 Signaling in Response to Viral and Bacterial Components

- The Relationship between Host Lifespan and Pathogen Reservoir Potential: An Analysis in the System

- Multiple Roles of the Cytoskeleton in Bacterial Autophagy

- The Evolution and Genetics of Virus Host Shifts

- ChIP-seq and In Vivo Transcriptome Analyses of the SREBP SrbA Reveals a New Regulator of the Fungal Hypoxia Response and Virulence

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Coronavirus Cell Entry Occurs through the Endo-/Lysosomal Pathway in a Proteolysis-Dependent Manner

- Peculiarities of Prion Diseases

- Host-Specific Parvovirus Evolution in Nature Is Recapitulated by Adaptation to Different Carnivore Species

- War and Infectious Diseases: Challenges of the Syrian Civil War

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání