-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Time for Global Action: Addressing Girls’ Menstrual Hygiene Management Needs in Schools

Marni Sommer and colleagues reflect on priorities needed to guide global, national, and local action to address girls' menstrual hygiene management needs in schools.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 13(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001962

Category: Health in Action

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001962Summary

Marni Sommer and colleagues reflect on priorities needed to guide global, national, and local action to address girls' menstrual hygiene management needs in schools.

Summary Points

There is an absence of guidance, facilities, and materials for schoolgirls to manage their menstruation in low - and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Formative evidence has raised awareness that poor menstrual hygiene management (MHM) contributes to inequity, increasing exposure to transactional sex to obtain sanitary items, with some evidence of an effect on school indicators and with repercussions for sexual, reproductive, and general health throughout the life course.

Despite increasing evidence and interest in taking action to improve school conditions for girls, there has not been a systematic mapping of MHM priorities or coordination of relevant sectors and disciplines to catalyze change, with a need to develop country-level expertise.

Columbia University and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) convened members of academia, nongovernmental organizations, the UN, donor agencies, the private sector, and social entrepreneurial groups in October 2014 (“MHM in Ten”) to identify key public health issues requiring prioritization, coordination, and investment by 2024.

Five key priorities were identified to guide global, national, and local action.

Introduction

A lack of adequate guidance, facilities, and materials for girls to manage their menstruation in school is a neglected public health, social, and educational issue that requires prioritization, coordination, and investment [1]. There are growing efforts from academia, the development sector, and beyond to understand and address the challenges facing menstruating schoolgirls in low - and middle-income countries (LMIC) [1]. A body of research has documented menstruating girls’ experiences of shame, fear, and confusion across numerous country contexts and the challenges girls face attempting to manage their menstruation with insufficient information, a lack of social support, ongoing social and hygiene taboos, and a shortage of suitable water, sanitation and waste disposal facilities in school environments [2–7]. The accruing evidence reveals the gender discriminatory nature of many school environments, with female students and teachers unable to manage their menstruation with safety, dignity, and privacy, negatively impacting their abilities to succeed and thrive within the school environment [7–9]. Poor school attainment reduces girls’ economic potential over the life course, impacts population health outcomes [9–12], and also extends to girls’ sexual and reproductive health outcomes, self-esteem, and sense of agency [4,7,8].

Despite increasing evidence about the challenges girls face managing menstruation in school in LMIC countries and growing efforts to address these challenges, there has not been a concentrated effort at global or national levels to identify key priorities to catalyze action to transform the school-going experiences of girls. The “MHM in Ten” initiative was organized by Columbia University and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) in New York City in October 2014 to systematically map out a ten-year agenda for overcoming the menstrual hygiene management (MHM)-related barriers facing schoolgirls.

Significant recent events supported the rationale for organizing such a meeting, illustratively including intense discussion around the inclusion of MHM in the post-2015 sustainable development goals, the investment by the Canadian government (Global Affairs Canada) to support MHM research and programming in 14 countries, the annual cohosting of the MHM in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) in Schools virtual conference by UNICEF and Columbia University, designation of May 28 as “Menstrual Hygiene Day,” and the development of a new puberty policy for the education sector with a focus on menstruation education and MHM by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This paper briefly describes the state of the evidence on MHM in schools, the remaining knowledge gaps, and potential action for making progress on the ten-year agenda.

Current Evidence: Knowledge and Gaps

In 2014, there were over 250 million girls aged 10–14 years of age living in less-developed countries, and nearly 56 million living in least-developed countries [13]. Although reliable evidence on the average age of menarche in many countries is lacking [14], the vast majority of girls will experience their first menstruation during this age range.

Growing evidence suggests the gendered impacts of inadequate WASH facilities in LMIC schools influence the participation of girls [15,16]. Much of the MHM research, conducted across sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and South America, has concentrated on understanding girls’ experiences of the onset of menstruation and the subsequent WASH challenges they face managing their menstruation in school [1]. Girls have indicated receiving inadequate guidance prior to their first menstrual period and experiencing fear, shame, and embarrassment managing menstruation, particularly while in school [4,6,7,17,18]. Studies have shown girls lack water, soap, privacy, and space to change [19]; adequate time to manage their menses comfortably, safely, and with dignity [20–22]; and hygienic sanitary products and sometimes underwear [7,23,24]. The latter lack may increase girls’ vulnerability to coercive sex and subsequent sexual and reproductive health harms to obtain money to buy sanitary products [25,26]. Female schoolteachers in many contexts also struggle to manage their menstruation comfortably and privately in schools and may be hard to retain in the absence of adequate WASH facilities; less evidence and action exist in relation to female teachers [27], but such work is needed. Many school systems have a predominance of male administrators and teachers, who may be unaware of or reluctant to talk about the challenges that schoolgirls and female teachers are facing [28]. Further contributing to unsupportive social environments at school, boy students report having little understanding about menstruation, and some tease and bully girls because they do not understand girls’ behaviors during menstruation [28–30]. This evidence has provided insights for some nascent programming and policy actions generally focused on three key MHM elements in school: the provision of MHM guidance, fostering an enabling physical and social school environment, and the distribution of menstrual products [2,31].

However, there remains a paucity of empirical evidence quantifying the extent and intensity of girls’ challenges managing menstruation, with few studies examining causal associations and little experimental evidence available to demonstrate the effectiveness of MHM interventions for health and schooling [32]. There has also been insufficient research examining the impact of inadequate MHM guidance or environments on schoolgirls’ levels of self-esteem, their self-efficacy to manage their menstruation in school, and their ability to concentrate in class when menstruating in schools that lack adequate WASH facilities or sensitized teachers and peers. There is also insufficient research examining the impact of interventions aimed at reducing menstrual-related bullying and improving girls’ self-confidence. This lack of evidence makes it difficult to promote recommendations to national governments, nongovernmental organizations, and others interested in integrating MHM into education and health strategies, and it reduces global buy-in to move this agenda forward. Lastly, while policy makers have called for increased measurement of school attendance, dropout, and educational attainment in relation to MHM, demonstrating quantitative associations with school absence in limited studies to date has shown minimal effect [5,33,34], despite strong qualitative evidence from girls’ narratives [4,7,17,26,35]. Similarly, self-reporting of reproductive tract infections among adolescent schoolgirls has also been shown to be unreliable without laboratory confirmation [36].

There are currently two distinct arguments put forward in relation to generating attention and resources to address inadequate MHM in schools. One frames the issues in relation to meeting the basic human rights and dignity of girls (and female teachers), while the second focuses on how ongoing barriers to effective MHM may contribute to negative health and education outcomes for girls. The global community has to some degree achieved consensus on the importance of the first but now needs to focus increased resources on generating adequate evidence for action on the second.

A Need for Collaboration across Sectors: MHM in Ten Aimed at Catalyzing Discussions across Sectors

Both the human rights argument and the need to improve MHM for health and educational reasons provide strong rationales for engagement from multiple sectors. However, while the MHM challenges facing pubescent girls in LMIC require cross-sectoral responses, funding streams and structures are needed to support sustainable activities by institutions and government ministries. Convergence between departments to prevent duplication and gaps similarly requires attention [37].

To date, much of the leadership and activities on MHM in schools has been through the WASH sector. The education sector has been less engaged, even though girls’ school experiences are negatively impacted if they are distracted, uncomfortable, or unable to participate because of anxiety over menstrual leakage and odor [7] or without the support of teachers, adequate latrines [20], or a place to rest if menstrual cramps become painful [4,31]. Girls’ sexual and reproductive health underscores the importance of engagement from the education sector given the evidence showing that educated girls are more likely to delay first sex, have fewer sexual partners, and use contraception and are less likely to become infected with HIV/AIDS. In terms of other population health gains, they are also more likely to have their children vaccinated and attend school and have healthier families [9,38–41]. MHM has yet to be included within the numerous activities underway to improve girls’ educational outcomes in LMICs.

There exists a window of opportunity to reach girls at menarche, as their bodies are biologically changing and they are encountering profound new social dynamics within their families and communities [42,43]. Many girls in LMIC receive no or factually incorrect guidance prior to menarche about the normal physiological process of menstruation or the pragmatics of MHM [8]. This in turn results in numerous misconceptions about their own fertility, creating vulnerability to adolescent pregnancy if girls are sexually active [7,9]. The adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) sector is called on to expand its focus and intervention timing beyond contraception (i.e., family planning) and disease prevention to include puberty and menstrual care guidance.

A range of stakeholders (see S1 Table) [44] discussed school environments, educational outcomes, SRH, gender, social beliefs, menstrual management products, and political commitment at the local, national, and global levels. The group included an array of expertise, comprising academics with varied experience conducting qualitative studies as well as randomized trials, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working in both advocacy and policy roles, bilateral donors and foundations, small and global level private sector corporations, and a range of UN agency perspectives. The under-representation of LMIC government representatives (i.e., Ministries of Education), country program managers, engineers, youth voices, and other key stakeholders at this first initiative was identified, and the organizers made a commitment to address this in subsequent meetings.

Priorities for Action

MHM in Ten participants defined a joint aim for the ten-year agenda: “Girls in 2024 around the world are knowledgeable about and comfortable with their menstruation and able to manage their menses in school in a comfortable, safe, and dignified way.”

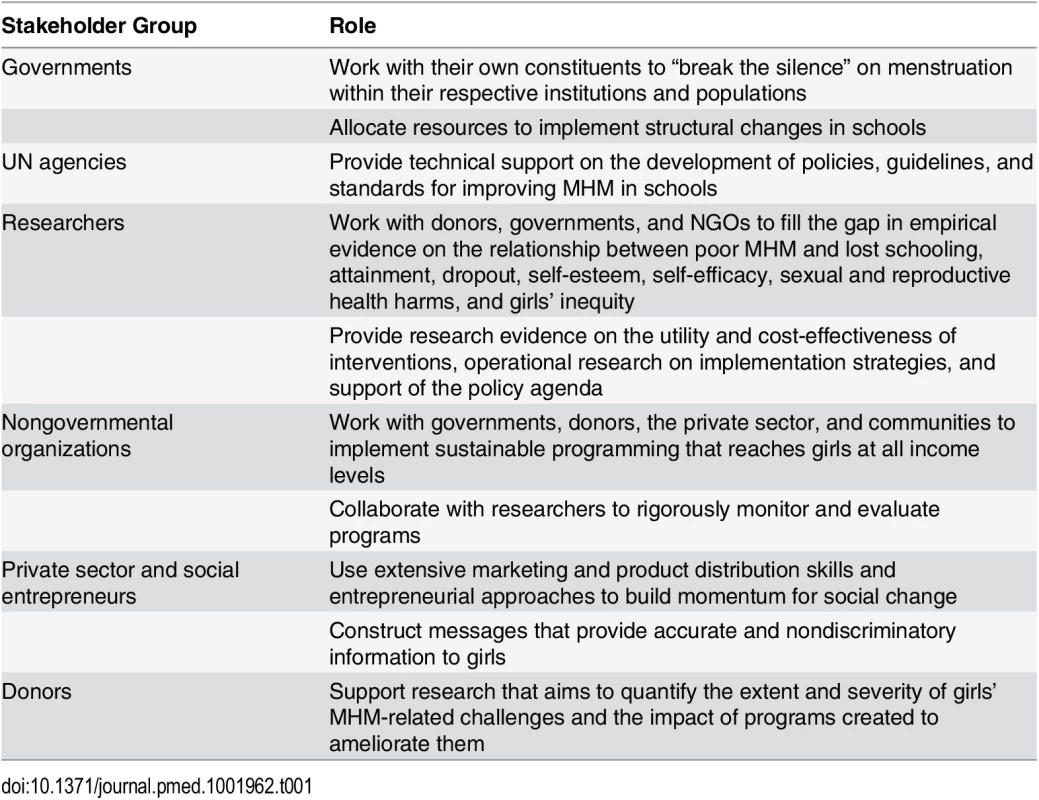

Five key priorities were identified to achieve this vision by 2024 (Table 1). The priorities are not intended to be sequential as some may happen in parallel:

Build a strong cross-sectoral evidence base for MHM in schools for prioritization of policies, resource allocation, and programming at scale. Specifically, rigorous impact evaluations of the most essential, cost-effective, and efficient interventions to implement in schools are needed, as well as a broader array of appropriate measures to capture the health and educational impacts of inadequate MHM. National-level research is still required to assure that policies, resources, and programs are appropriate and effective.

Develop and disseminate global guidelines for MHM in schools with minimum standards, indicators, and illustrative strategies for adaptation, adoption, and implementation at national and subnational levels. The absence of accepted global guidelines and indicators for what to implement in schools and how to monitor interventions is paralyzing governments, school systems, and other practitioners who want guidance for action.

Advance MHM in schools activities through a comprehensive evidence-based advocacy platform that generates policies, funding, and action across sectors and at all levels of government. There is a need for improved advocacy around MHM given taboos in many countries that hinder open discussion about addressing MHM in schools and the stakeholder engagement needed at all levels (i.e., governments, donors, parents teachers, and students).

Allocate responsibility to designated government entities for the provision of MHM in schools (including adequate budget and monitoring and evaluation [M&E]) and the reporting to global channels and constituents, recognizing that scalable impact on MHM in schools will only occur when national governments take responsibility for and perceive MHM as a priority for education systems, which highlights their role for change in the coming ten years.

Integrate MHM and the capacity and resources to deliver inclusive MHM into the education system. The education sector recognizes and demonstrates MHM as an integral part of its resources, plans, budgets, services, and performance monitoring and delivers inclusive educational service to all children and adolescents. Numerous components of action are needed within a given educational system to assure action and monitoring of MHM interventions in schools, and such actions need to be inclusive of vulnerable groups, including girls with disabilities.

Tab. 1. Illustrative cross-sectoral actions to meet priorities.

Recognized Challenges and Opportunities to Achieving Goals

There are challenges to moving forward the MHM agenda in the next ten years; however, there is reason for optimism.

There are competing priorities in the health and education spheres for the existing development resources for adolescent girls. Integrating MHM into existing programming and policy could be a noncompetitive and cost-effective approach. The provision of puberty and menstruation education booklets to girls getting the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has been suggested as a potential integrated strategy.

The majority of existing efforts aimed at addressing MHM have emerged from the WASH community, yet the WASH sector alone cannot advance the MHM agenda in schools. MHM in schools must be supported by a diverse range of actors globally and within countries (i.e., Ministries of Education, Health, Finance, Sanitation and Water, and Women and Children’s Affairs), including any other government specific entities at the country level holding responsibility due to the legal and competence frame of each country (see Table 1 for examples). The current 14-country WASH in Schools (WinS) for Girls program led by UNICEF with support from the Canadian government aims to conduct local research and use findings to generate a platform for action. To ensure multisector involvement, the program has required participating countries form in-country working groups with representatives from the government, local research institutions, and NGOs so varied feedback can be integrated throughout the process. The lessons learned from this effort can serve as a model for multiactor efforts moving forward.

Evidence-based interventions require robust research to support cost-effective programming, and the latter will require an increase in dedicated resources to support the trials needed to generate the data for decision making. Funding is now occurring; for example, the UK-based Department for International Development, Medical Research Council, and Wellcome Trust are supporting a large-scale trial evaluating the effect of menstrual cups on Kenyan girls’ school and SRH outcomes.

The Way Forward

Participants identified key next steps to reach these priorities:

A first step is for stakeholders to develop an operational strategy for the MHM in Ten agenda that includes a M&E component for assessing current status and progress in addressing the five priorities. This includes collection of standardized indicators generated at the national level. Buy-in from national governments and schoolgirls themselves is essential.

A second step is to build collaboration and strengthen research capacity across countries and regions of the world on MHM. It is critical to identify existing, or foster new, MHM experts and actors in each country, whether through strengthening research capacity of in-country academics to conduct local research on MHM or through efforts to mobilize MHM stakeholders within the country to generate collaboration and activity. A global repository for existing evidence, programs, and policies on MHM in schools will provide a platform for decision making. Fostering essential research would be supported through a research consortia. A research concept note detailing the existing gaps in the evidence has been developed [45]; however, a collation and review of the lessons learned to date from existing programming and policy is needed.

A third step is to coordinate progress and share outcomes, bringing together country - and global-level stakeholders. A steering group comprising global and local expertise, meeting at least annually, and supported through a UN agency would facilitate this.

Conclusion

There have been numerous early accomplishments in the nascent MHM field in the last few years. In order to reach the vision of girls around the world being knowledgeable about and comfortable with their menstruation and able to manage it safely and with dignity in school, global support of the priorities identified at MHM in Ten is required to make sustainable change by 2024.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Sommer M, Hirsch JS, Nathanson C, Parker RG (2015) Comfortably, Safely, and Without Shame: Defining Menstrual Hygiene Management as a Public Health Issue. Am J Public Health 105 : 1302–1311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525 25973831

2. Sommer M, Sahin M (2013) Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. Am J Public Health 103 : 1556–1559. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301374 23865645

3. Van der Walle E, Remme E (2001) Regulating Menstruation: Beliefs, Practices, Interpretations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

4. McMahon SA, Winch PJ, Caruso BA, Obure AF, Ogutu EA, Ochari IA, et al. (2011) 'The girl with her period is the one to hang her head' Reflections on menstrual management among schoolgirls in rural Kenya. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 11 : 7. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-7 21679414

5. Montgomery P, Ryus CR, Dolan CS, Dopson S, Scott LM (2012) Sanitary pad interventions for girls' education in Ghana: a pilot study. PLoS ONE 7: e48274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048274 23118968

6. Mahon T, Fernandes M (2010) Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: a neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programmes. Gender & Development 18 : 99–113.

7. Mason L, Nyothach E, Alexander K, Odhiambo FO, Eleveld A, Vulule J, et al. (2013) 'We keep it secret so no one should know'—a qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural Western kenya. PLoS ONE 8: e79132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079132 24244435

8. Sommer M, Sutherland C, Chandra-Mouli V (2015) Putting menarche and girls into the global population health agenda. Reprod Health 12 : 24. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0009-8 25889785

9. Herz B, Sperling G (2004) What works in girls' education:evidence and policies from the developing world. Council on Foreign Relations.

10. Chaaban J, Cunningham W (2011) Measuring the Economic Gain of Investing in Girls—The Girl Effect Dividend. Washington, DC: World Bank. 5753 5753.

11. Rihani A (2006) Keeping the Promise: Five Benefits of Girls Secondary Education Washington DC: McCauley and Salter.

12. UNESCO (2012) Youth and skills: Putting education to work. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

13. Census (2015) Bureau U.S.A Accessed March 20 2015: http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/informationGateway.php

14. Sommer M (2013) Menarche: a missing indicator in population health from low-income countries. Public Health Rep 128 : 399–401. 23997288

15. Freeman MC, Greene LE, Dreibelbis R, Saboori S, Muga R, Brumback B, et al. (2012) Assessing the impact of a school-based water treatment, hygiene and sanitation programme on pupil absence in Nyanza Province, Kenya: a cluster-randomized trial. Trop Med Int Health 17 : 380–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02927.x 22175695

16. Garn JV, Greene LE, Dreibelbis R, Saboori S, Rheingans RD, Freeman MC (2013) A cluster-randomized trial assessing the impact of school water, sanitation, and hygiene improvements on pupil enrollment and gender parity in enrollment. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 3: doi: 10.2166/washdev.2013.2217 24392220

17. Sommer M (2010) Where the education system and women's bodies collide: The social and health impact of girls' experiences of menstruation and schooling in Tanzania. J Adolesc 33 : 521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.008 19395018

18. Thakur H, Aronsson A, Bansode S, Lundborg CS, Dalvie S, Faxelid E (2014) Knowledge, practices and restrictions related to menstruation among young women from low socioeconomic community in Mumbai, India. Frontiers in Public Health 2 : 2–7.

19. Alexander K, Oduor C, Nyothach E, Laserson K, Amek N, Eleveld A, et al. (2014) Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Conditions in Kenyan Rural Schools: Are Schools Meeting the Needs of Menstruating Girls? Water 6 : 1453–1466.

20. Oduor C, Alexander K, Oruko K, Nyothach E, Mason L, Odhiambo F, et al. (2015) Schoolgirls’ experiences of changing and disposal of menstrual hygiene items and inferences for WASH in schools. Waterlines 34 : 397–411.

21. Fehr A (2011) Stress, menstruation and school attendance: effects of water access among adolescent girls in south Gondar, Ethiopia. Atlanta, GA: Emory University.

22. Sommer M, Ackatia-Armah T (2012) The gendered nature of schooling in Ghana: hurdles to girls' menstrual management in school JENdA 20 : 63–79.

23. Long J, Caruso B, Lopez D, Vancraeynest K, Sahin M, Andes K, et al. (2013) WASH in Schools Empowers Girls' Education in Rural Cochabamba: An Assessment of Menstrual Hygiene Management in Schools. New York.

24. Crofts T, Fisher WA (2012) Menstrual Hygiene in Ugandan Schools and investigation of low-cost sanitary pads. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 2 : 50–58.

25. Phillips-Howard PA, Otieno G, Burmen B, Otieno F, Odongo F, Odour C, et al. (2015) Menstrual Needs and Associations with Sexual and Reproductive Risks in Rural Kenyan Females: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Survey Linked with HIV Prevalence. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 24 : 1–11.

26. Oruko K, Nyothach E, Zielinski-Gutierrez E, Mason L, Alexander K, Vulule J, et al. (2015) 'He is the one who is providing you with everything so whatever he says is what you do': A Qualitative Study on Factors Affecting Secondary Schoolgirls' Dropout in Rural Western Kenya. PLoS ONE 10: e0144321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144321 26636771

27. Pearson J, McPhederan K (2008) A literature review of the non-health impacts of sanitation. Waterlines 27 : 48–61.

28. Mahon T, Tripathy A, Singh N (2015) Putting the men into menstruation: the role of men and boys in community menstrual hygiene management. Waterlines 34 : 7–14.

29. Chang YT, Lin ML (2013) Menarche and menstruation through the eyes of pubescent students in eastern Taiwan: implications in sociocultural influence and gender differences issues. J Nurs Res 21 : 10–18. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182829b26 23407333

30. Panakalapati G (2013) "Boys don't have knowledge about menstruation; they think it is a bad thing": Knowledge and Beliefs about Menstruation among Adolescent Boys in Gicumbi District, Rwanda’ Atlanta, GA: Emory University.

31. Sommer M, Cherenack E, Blake S, Sahin M, Burgers L (2015) WASH in Schools Empowers Girls' Education: Proceedings of the Menstrual Hygiene Management in Schools Virtual Conference 2014. New York, USA: United Nations Children's Fund and Colombia University.

32. Sumpter C, Torondel B (2013) A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. PLoS ONE 8: e62004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062004 23637945

33. Grant MJ, Lloyd CB, Mensch BS (2013) Menstruation and School Absenteeism: Evidence from Rural Malawi. Comp Educ Rev 57 : 260–284. 25580018

34. Oster E, Thornton R (2011) Menstruation, Sanitary Products and School Attendance: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation. Am Econ J: Appl Economics 3 : 91–100.

35. Mason L, Laserson K, Oruko K, Nyothach E, Alexander K, Odhiambo F, et al. (2015) Adolescent schoolgirls’ experiences of menstrual cups and pads in rural western Kenya: a qualitative study. Waterlines 34 : 15–30.

36. Kerubo E, Laserson K, Otecko N, Odhiambo C, Mason L, Nyothach E, et al. (2016) Prevalence of reproductive tract infections and the predictive value of girls’ symptom-based reporting: findings from a cross sectional survey in rural western Kenya. jSTI (in press).

37. Muralidharan A, Patil H, Patnaik S (2015) Unpacking the policy landscape for menstrual hygiene management: implications for school WASH programmes in India. Waterlines 34 : 79–91.

38. Hahn RA, Truman BI (2015) Education Improves Public Health and Promotes Health Equity. Int J Health Serv doi: 10.1177/0020731415585986

39. Jukes M, Simmons S, Bundy D (2008) Education and vulnerability: the role of schools in protecting young women and girls from HIV in southern Africa. AIDS 22 Suppl 4: S41–56. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341776.71253.04 19033754

40. Biddlecom A, Gregory R, Lloyd CB, Mensch BS (2008) Associations between premarital sex and leaving school in four sub-Saharan African countries. Stud Fam Plann 39 : 337–350. 19248719

41. Hargreaves J, Morison L, Kim J, Bonell C, Porter J, al. e (2008) The association between school attendance, HIV infection and sexual behaviour among young people in rural South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health 62 : 113–119. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053827 18192598

42. Sommer M (2011) An overlooked priority: puberty in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health 101 : 979–981. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300092 21493937

43. Blum R, Mmari K (2006) Risk and protective factors affecting adolescent reproductive health in developing countries: an analysis of adolescent sexual and reproductive health literature from around the world. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

44. UNICEF (2014) MHM in Ten: advancing the MHM in WASH in Schools agenda. New York: UNICEF and Columbia University.

45. Phillips-Howard P, Caruso B, Torondel B, C C, Sahin M, Sommer M (2015) Menstrual Hygiene Management for Adolescent girls: Priorities and call for a research consortia (Concept Note).

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek 2015 Reviewer Thank You

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2016 Číslo 2- Berberin: přírodní hypolipidemikum se slibnými výsledky

- Léčba bolesti u seniorů

- Příznivý vliv Armolipidu Plus na hladinu cholesterolu a zánětlivé parametry u pacientů s chronickým subklinickým zánětem

- Červená fermentovaná rýže účinně snižuje hladinu LDL cholesterolu jako vhodná alternativa ke statinové terapii

- Jak postupovat při výběru betablokátoru − doporučení z kardiologické praxe

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- 2015 Reviewer Thank You

- The Future of Diabetes Prevention: A Call for Papers

- The Case for Reforming Drug Naming: Should Brand Name Trademark Protections Expire upon Generic Entry?

- The Health Care Consequences Of Australian Immigration Policies

- Microenvironmental Heterogeneity Parallels Breast Cancer Progression: A Histology–Genomic Integration Analysis

- Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in China: Modeling Epidemic Dynamics of Enterovirus Serotypes and Implications for Vaccination

- Estimated Effects of Different Alcohol Taxation and Price Policies on Health Inequalities: A Mathematical Modelling Study

- Effect of Short-Term Supplementation with Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food or Micronutrients for Children after Illness for Prevention of Malnutrition: A Randomised Controlled Trial in Uganda

- Effect of Short-Term Supplementation with Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food or Micronutrients for Children after Illness for Prevention of Malnutrition: A Randomised Controlled Trial in Nigeria

- When Children Become Adults: Should Biobanks Re-Contact?

- Transforming Living Kidney Donation with a Comprehensive Strategy

- A Time for Global Action: Addressing Girls’ Menstrual Hygiene Management Needs in Schools

- The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers

- Risk of Injurious Fall and Hip Fracture up to 26 y before the Diagnosis of Parkinson Disease: Nested Case–Control Studies in a Nationwide Cohort

- Mortality, Morbidity, and Developmental Outcomes in Infants Born to Women Who Received Either Mefloquine or Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine as Intermittent Preventive Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy: A Cohort Study

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in China: Modeling Epidemic Dynamics of Enterovirus Serotypes and Implications for Vaccination

- A Time for Global Action: Addressing Girls’ Menstrual Hygiene Management Needs in Schools

- Transforming Living Kidney Donation with a Comprehensive Strategy

- The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání