-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaParallel Germline Infiltration of a Lentivirus in Two Malagasy Lemurs

Retroviruses normally infect the somatic cells of their host and are transmitted horizontally, i.e., in an exogenous way. Occasionally, however, some retroviruses can also infect and integrate into the genome of germ cells, which may allow for their vertical inheritance and fixation in a given species; a process known as endogenization. Lentiviruses, a group of mammalian retroviruses that includes HIV, are known to infect primates, ruminants, horses, and cats. Unlike many other retroviruses, these viruses have not been demonstrably successful at germline infiltration. Here, we report on the discovery of endogenous lentiviral insertions in seven species of Malagasy lemurs from two different genera—Cheirogaleus and Microcebus. Combining molecular clock analyses and cross-species screening of orthologous insertions, we show that the presence of this endogenous lentivirus in six species of Microcebus is the result of one endogenization event that occurred about 4.2 million years ago. In addition, we demonstrate that this lentivirus independently infiltrated the germline of Cheirogaleus and that the two endogenization events occurred quasi-simultaneously. Using multiple proviral copies, we derive and characterize an apparently full length and intact consensus for this lentivirus. These results provide evidence that lentiviruses have repeatedly infiltrated the germline of prosimian species and that primates have been exposed to lentiviruses for a much longer time than what can be inferred based on sequence comparison of circulating lentiviruses. The study sets the stage for an unprecedented opportunity to reconstruct an ancestral primate lentivirus and thereby advance our knowledge of host–virus interactions.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 5(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000425

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000425Summary

Retroviruses normally infect the somatic cells of their host and are transmitted horizontally, i.e., in an exogenous way. Occasionally, however, some retroviruses can also infect and integrate into the genome of germ cells, which may allow for their vertical inheritance and fixation in a given species; a process known as endogenization. Lentiviruses, a group of mammalian retroviruses that includes HIV, are known to infect primates, ruminants, horses, and cats. Unlike many other retroviruses, these viruses have not been demonstrably successful at germline infiltration. Here, we report on the discovery of endogenous lentiviral insertions in seven species of Malagasy lemurs from two different genera—Cheirogaleus and Microcebus. Combining molecular clock analyses and cross-species screening of orthologous insertions, we show that the presence of this endogenous lentivirus in six species of Microcebus is the result of one endogenization event that occurred about 4.2 million years ago. In addition, we demonstrate that this lentivirus independently infiltrated the germline of Cheirogaleus and that the two endogenization events occurred quasi-simultaneously. Using multiple proviral copies, we derive and characterize an apparently full length and intact consensus for this lentivirus. These results provide evidence that lentiviruses have repeatedly infiltrated the germline of prosimian species and that primates have been exposed to lentiviruses for a much longer time than what can be inferred based on sequence comparison of circulating lentiviruses. The study sets the stage for an unprecedented opportunity to reconstruct an ancestral primate lentivirus and thereby advance our knowledge of host–virus interactions.

Introduction

Lentiviruses are mammalian retroviruses known to infect cattle, cats, horses, sheep, and primates. They are the focus of intense study due to their causative association with AIDS in human. Although our knowledge on the origin and early evolution of HIV has grown exponentially over the past few years [1],[2], much remains unresolved about the deeper relationships between primate and non-primate lentiviruses, the origin of lentiviruses, and their mode of structural evolution over long periods of evolutionary time. This is because these viruses evolve extremely rapidly [3], in a conflicting relationship with their hosts [4], and while their high mutation rate provides a wealth of information documenting their recent history, it also quickly erases evidence of their deeper ancestry.

The lifecycle of retroviruses is atypical compared to other viruses in that after appropriate receptor recognition and entry in a specific cell type, their RNA genome is reverse transcribed into double-stranded DNA and integrated into the host genome as a provirus [5]. Occasionally this process can take place in the host germline, and the integrated copy, also called endogenous retrovirus (ERV), may be transmitted vertically from parent to offspring and reach fixation in the host population. As such, ERVs constitute a “fossil record” of past viral infections that potentially provide an alternative way of gaining insights into the deep evolutionary history of present day exogenous retroviruses [6].

Although many ERVs have been characterized in mammals (e.g., 8% of the human genome), apparently very few derive from lentiviruses. Two reasons have traditionally been put forward to explain their absence in mammalian genomes: (i) they are of relatively recent evolutionary origin and endogenization has not yet commonly occurred, and/or (ii) they were not able to enter germ cells because of a very specific cell tropism [7],[8]. Recently however, an endogenous lentivirus, called RELIK, has been identified in the genome of rabbits and hares (Lagomorpha), whose germline integration was dated at least 12 millions years (my) old [9]–[11]. This discovery not only showed that lentiviruses were able to infiltrate mammalian germlines, but also demonstrated that this group of viruses is probably much older than what could previously be inferred based on sequence comparison of extant exogenous lentiviruses.

Even more recently, Gifford et al. [12] described the remnants of an endogenous lentivirus in the genome of the prosimian primate Microcebus murinus. This virus, called pSIVgml for “gray mouse lemur prosimian immunodeficiency virus”, represents the first example of a primate endogenous lentivirus. Here we report on our independent discovery and characterization of pSIVgml and of a second, closely related endogenous prosimian lentivirus, pSIVfdl, which independently colonized the genome of the fat-tailed dwarf lemur Cheirogaleus medius. Our analyses of these defective proviral sequences corroborate and expand the findings of Gifford et al. [12] and allow us to reconstruct an apparently full-length and intact pSIV consensus sequence that provides new insights into the evolutionary history of lentiviruses and should permit functional analysis of an ancestral primate lentivirus.

Results/Discussion

Discovery of an Endogenous Lentivirus in the Gray Mouse Lemur Genome

Homology based searches (tBLASTn) of whole genome shotgun (WGS) sequences using the rabbit endogenous lentivirus (RELIK) consensus sequence [9] as a query yielded highly significant hits in the gag and pol domains to two contigs from the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) genome sequencing project (Table 1). Further BLASTn searches on the M. murinus WGS sequences (1.93× June 2007 release) using the M. murinus pol-containing contig (ABDC01505939) as a query yielded ten other contigs containing a fragment highly similar to the region situated upstream of the pol domain, i.e., the presumed long terminal repeat (LTR). Five of these fragments (413–423 bp in length) are flanked by short direct repeats akin to target site duplications (TSD, Table 1) and therefore likely correspond to solo LTRs resulting from intra-element recombination [13]. Four other hits correspond to LTRs truncated due to sequencing or assembly gap, and one corresponds to a 3′ full-length LTR flanking an env domain also truncated due to a gap.

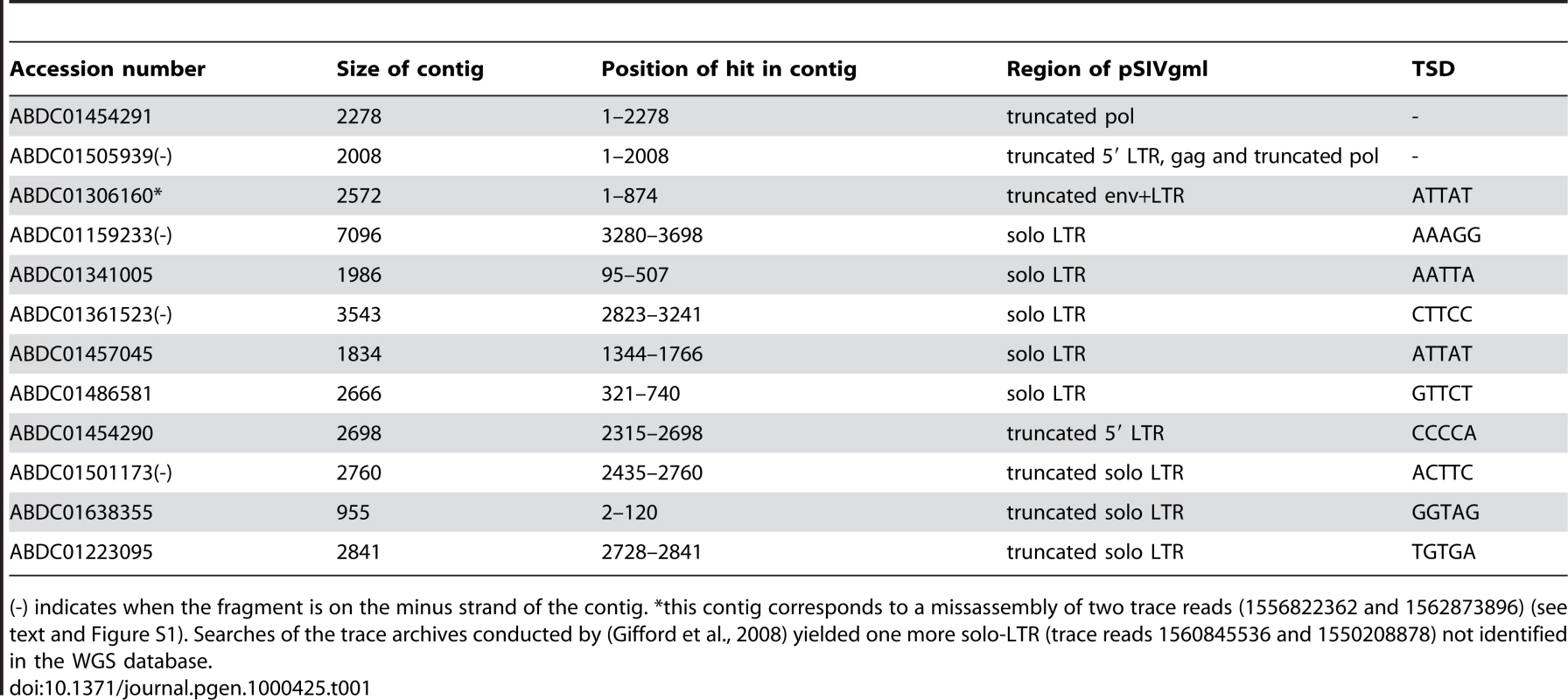

Tab. 1. Summary of all the fragments of pSIVgml found in the whole genome shotgun sequence database of the gray mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus (1.93× coverage).

(-) indicates when the fragment is on the minus strand of the contig. *this contig corresponds to a missassembly of two trace reads (1556822362 and 1562873896) (see text and Figure S1). Searches of the trace archives conducted by (Gifford et al., 2008) yielded one more solo-LTR (trace reads 1560845536 and 1550208878) not identified in the WGS database. These results are broadly consistent with Gifford et al. [12] who undertook an approach similar to ours, except that these authors also searched the trace archives database and found an additional solo-LTR that we did not detect in the WGS database (Table 1). Below we confirm that these proviral fragments correspond to an endogenous lentivirus identical to the one described in [12] and thus we adopt the nomenclature introduced by these authors who named this lentivirus pSIVgml for gray mouse lemur prosimian immunodeficiency virus.

Copy Number and Taxonomic Distribution

The coverage of the gray mouse lemur genome is low (1.93×) and its assembly still very fragmentary, implying that any estimate of pSIVgml copy number based only on database mining will be tentative at best. Two of the pSIVgml LTRs in the M. murinus WGS were associated to internal coding sequences (contig ABDC01454290/ ABDC01505939 and contig ABDC01306160) suggesting that they represent the 5′ and 3′ LTRs of seemingly full-length proviruses. Since these LTRs were not flanked by the same TSD (CCCCA vs. ATTAT) (Table 1, Figure 1), Gifford et al. [12] concluded that at least two distinct full-length proviral insertions must exist in the genome of M. murinus. Based on this observation and assuming that the amount of sequence deposited in the WGS database corresponds roughly to 30% of the complete Microcebus genome, the authors estimated that there may be up to six full length copies of pSIVgml [12].

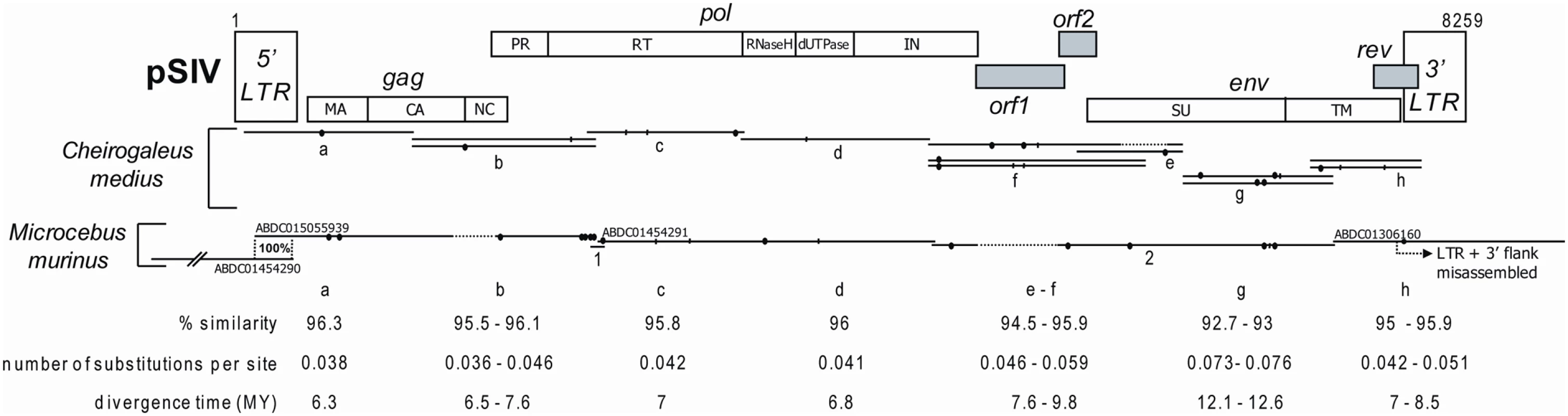

Fig. 1. Map of the consensus pSIV reconstructed in this study based on one full-length copy of pSIVgml (Microcebus murinus) and between one and three copies of pSIVfdl (Cheirogaleus medius) (the alignment is provided in Dataset S1).

The LTR fragments contained in the ABDC01505939 and ABDC01454290 contigs correspond to the same full length pSIV copy (see Figure S1). The contig ABDC01306160 results from a misassembly between a trace read containing a solo-LTR and a trace read containing the 3′ terminus of the env of the full-length pSIVgml and a fragment of the 3′ LTR (see Figure S1). The different domains of pSIV were identified by comparison with the HIV1-HXB2 reference sequence [40] (see Figure S4 for a more precise map). Closed circles: non-sense frameshifts. Vertical bars: in frame stop codons. Dash lines: missing fragments. The range of pairwise similarity, number of substitutions per site and inferred divergence times between pSIVgml and pSIVfdl sequences are indicated. As a more direct approach to estimate the copy number of pSIVgml and to screen for the possible presence of related endogenous lentiviruses in related prosimian species, we performed Southern hybridizations of digested total genomic DNA from M. murinus, nine other species of Malagasy lemurs and Homo sapiens as a negative control. A ∼1-kb probe corresponding to a fragment of the pSIVgml env gene revealed only one band in M. murinus (Figure 2A), which was inconsistent with the copy number estimate based on database mining (i.e. between two and six full length copies) [12]. In order to identify the origin of this discrepancy, we sought to validate the WGS draft assembly of M. murinus using PCR with primers anchored in the sequence reads used for the initial assembly. We were able to confirm that contigs ABDC01454290 and ABDC01505939 can be assembled into a single contig containing a 5′ LTR adjacent to a gag and partial pol genes, indicating that this locus is likely to correspond to a full-length proviral insertion (Figure S1). We were unable to recover any PCR products using a forward primer located in the env region and a reverse primer located in the assigned 3′ flanking region of contig ABDC01306160 (Figure S1). We also observed that the two trace reads (1556822362 and 1562873896) used to assemble contig ABDC01306160 overlap within the LTR, which suggests that the env region could have been misassembled to an illegitimate 3′ LTR. We suspected that this env gene was in fact associated with the full-length proviral insertion aforementioned and characterized by the CCCCA TSD (Figure S1). This was confirmed by amplifying a PCR product spanning the env region, 3′ LTR and flanking genomic DNA with the CCCCA 3′ TSD. Sequencing of this PCR product revealed 100% identity with the env gene in contig ABDC01306160 (Figure S1), suggesting that indeed we had connected the single env gene present in the genome to its legitimate 3′ LTR. Together with the Southern results, these data point to the presence of a single full-length pSIVgml provirus in the M. murinus genome and that contig ABDC01306160 is the result of a misassembly in the draft genome sequence.

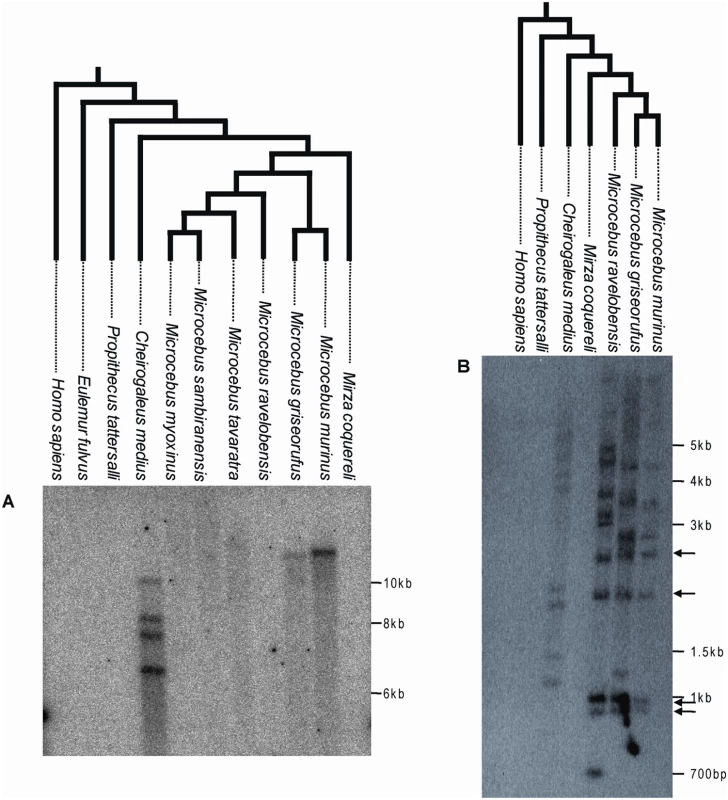

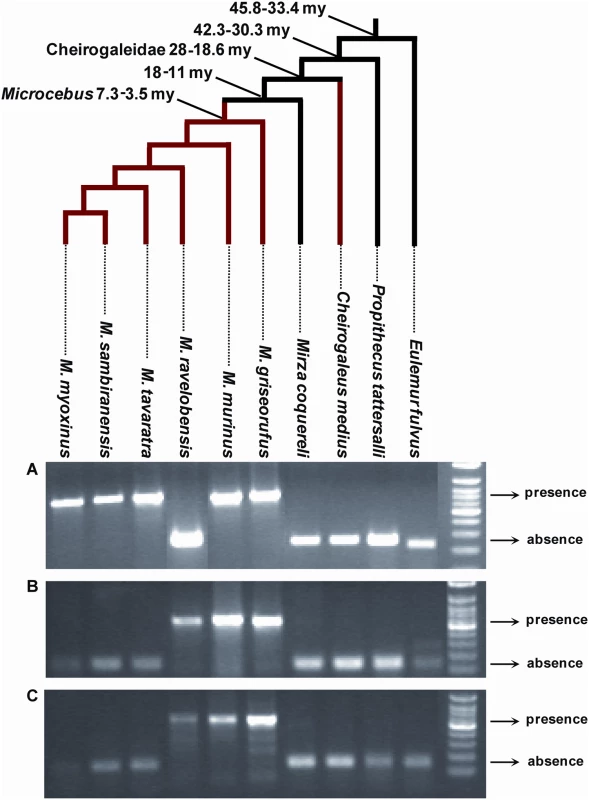

Fig. 2. Southern blot of digested genomic DNA of various Malagasy lemurs and human using a ∼1 kb probe corresponding to a fragment of pSIVgml env (A) or a ∼300 bp probe corresponding to a fragment of the pSIV LTR (B).

Arrows highlight bands of the same size shared by Microcebus murinus, M. griseorufus and M. ravelobensis but not Cheirogaleus medius. These bands likely correspond to solo-LTRs located at orthologous position in the three Microcebus species. The trees on top of each blot depict the phylogenetic relationships of the species according to [23],[41]. See Table S4 for the voucher specimen numbers of the lemur tissue samples used in this study. A picture of the ethidium bromide stained gels used to prepare the blots is shown in Figure S2. The absence of pSIV in Mirza was confirmed by PCR using different sets of primers (Figure S3). The Southern analysis showed that pSIV is not restricted to the gray mouse lemur but is also present in low copy number in several additional Malagasy lemurs. The env probe revealed one band in M. griseorufus, four bands in Cheirogaleus medius and no bands in the other lemur species examined (M. ravelobensis, M. myoxinus, M. tavaratra, M. sambiranensis, Mirza coquereli, Propithecus tattersalli, Eulemur fulvus rufus) (Figure 2A; see also Figure S2A, Figure S3). A second probe corresponding to a ∼300-bp LTR fragment hybridized with 8 to 11 genomic fragments in M. griseorufus, M. murinus, M. ravelobensis, and C. medius but yielded no hybridization in the three other lemur species (Figure 2B, Figure S2B). Assuming no intra-element restriction site polymorphism, these results suggest that there are at least four potentially full-length (i.e., insertions including some coding region, as opposed to solo LTR) pSIV proviruses in Cheirogaleus and only one in M. murinus and M. griseorufus. The genomes of M. ravelobensis, M. myoxinus, M. tavaratra and M. sambiranensis seem to harbor only solo LTRs, and pSIV is absent from Mirza, Propithecus, and Eulemur.

Reconstruction of a pSIV Consensus

Using PCR primers (Table S1) designed upon the pSIVgml-containing contigs, we sequenced the missing fragments of pSIVgml in Microcebus murinus and multiple clones covering what appears to represent a full-length pSIV in Cheirogaleus medius (Figure 1; Dataset S1) that we named pSIVfdl for “fat-tailed dwarf lemur prosimian immunodeficiency virus”, following the nomenclature introduced by Gifford et al. [12]. The pSIV sequences obtained in both species of these two genera contain a substantial amount of frameshifts, stop codons, and some large deletions, indicating that the pSIV insertions are defective and relatively ancient. Sequence similarity between pSIVgml and pSIVfdl is remarkably high (93–96%) compared to the genetic diversity observed within HIV-1 subtypes (80–85%) [14], suggesting that the viruses endogenized in the two lemur species were nearly identical. We therefore decided to use all sequences from both species to reconstruct a single pSIV consensus (Figure 1 and S4).

Though overall the structure of our pSIV consensus is largely consistent with the pSIVgml sequence reported by Gifford et al. [12], the inclusion of additional pSIVfdl proviral copies (from Cheirogaleus) allowed us to fill several gaps that are apparent in pSIVgml. The revised pSIV consensus is now free of stop codons and non-sense frameshifts since none of the mutations was shared between pSIVgml and the various pSIVfdl copies. In addition, the fragment including the 3′ end of the capsid, nucleocapsid and the 5′ end of the protease domains that is missing in the pSIVgml sequence (Figure 1, this study; Figure 1 in [12]) was present in the two pSIVfdl clones overlapping the gag and pol genes (clones d; Figure 1). Close inspection of the complete gag-pol junction revealed that the translation of the pol gene is most likely regulated via −1 frameshifting (Figure S4), which is characteristic of most known retroviruses [5].

We confirm the presence of a putative rev accessory gene overlapping with the 3′ end of the env open reading frame (ORF), but the two different copies of pSIVfdl included in our analysis do not contain the stop codon separating the rev gene from the putative terminal small ORF identified in [12]. Consequently, the putative rev gene characterized here encompasses the sequence corresponding to this 3′ putative ORF and terminates with a motif rich in leucine residues, characteristic of the nuclear export signals found in rev and other nuclear transporters [15],[16].

The most significant difference between the pSIV consensus and the previously reported pSIVgml sequence [12] lies in the region situated between pol and env. The three different pSIVfdl clones covering this region (clones f1, f2 and e1) all contain a 511-bp region that is apparently deleted in pSIVgml (Figure 1). Analysis of the complete pol-env intervening region revealed two small overlapping ORFs that we named orf1 and orf2. The 5′ end of orf1 slightly overlaps with the end of pol while its 3′ end comprises the first 22 amino acid (aa) of the putative vif identified in [12]. The sequence for orf2 largely overlaps with the initially characterized vif while the start of env corresponds to the start of the putative tat accessory gene proposed in [12]. We could not detect any significant similarity between orf1 (199 aa) and orf2 (83 aa) and any known lentiviral accessory gene, but we note that they are located at a comparable genomic position than vif and tat, i.e., between pol and env, and the predicted proteins are very similar in size to those encoded by these accessory genes in other primate lentiviruses (vif is 192 aa and tat is 86 aa in HIV1-HXB2). Thus, it is possible that these pSIV ORFs encode vif and tat homologs.

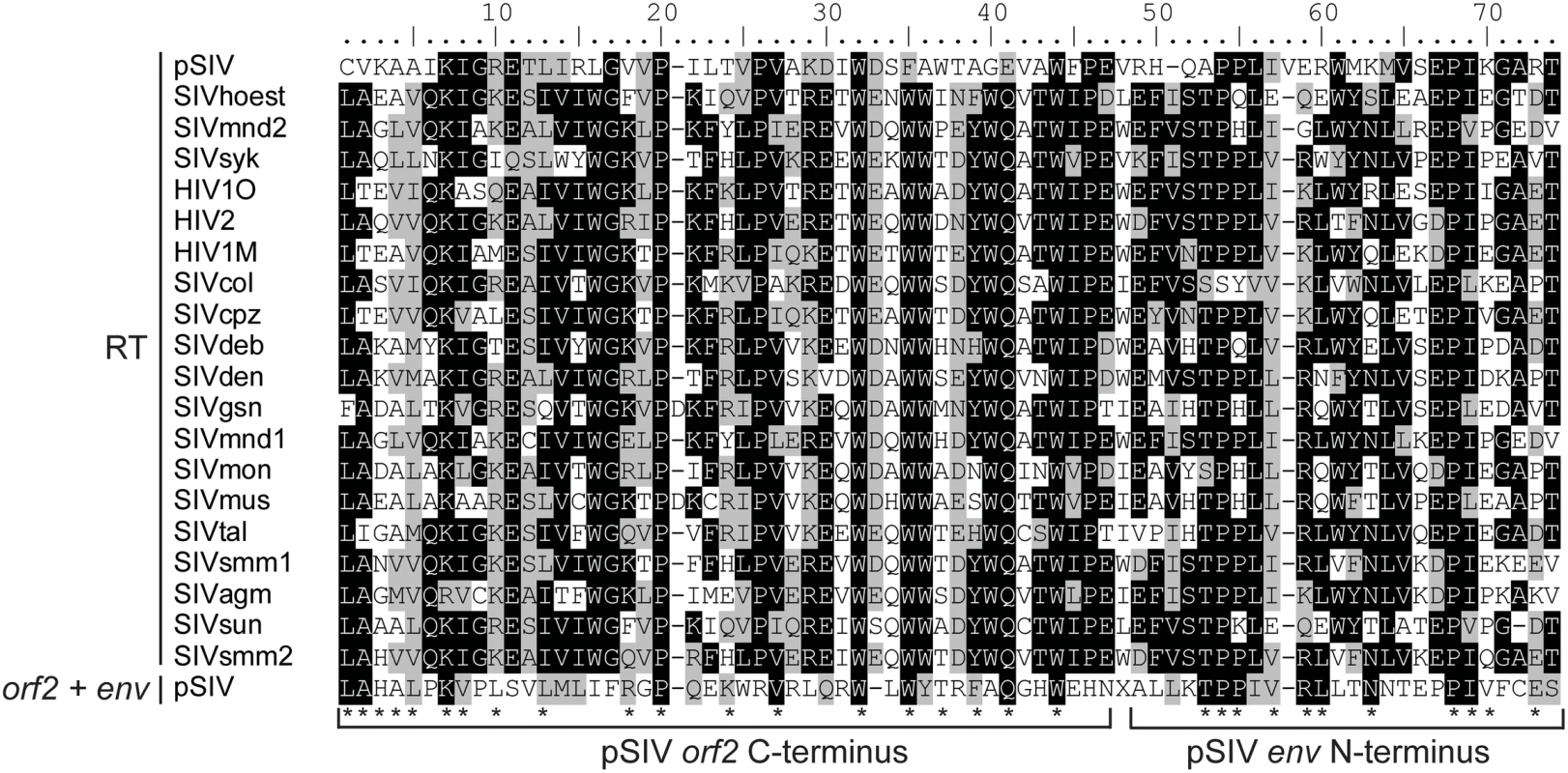

Interestingly, tBLASTn searches using the pSIV consensus as query yielded weak but significant similarity (e-value = 0.041) with the C-terminus of the reverse transcriptase encoded by primate lentiviruses in a region of pSIV including 46 aa of the orf2 C-terminus and 25 aa of the env N-terminus (Figure 3). This is reminiscent of the situation reported for HIV-2, where the vpx gene (found only in HIV-2) shows significant similarity to the vpr gene (found in all simian lentiviruses) [17]. Based on this observation and on phylogenetic analyses of different simian lentiviruses, it has been proposed that vpx originated through non-homologous recombination between one strain of SIV and an early ancestor of HIV-2 [18],[19]. Likewise, non-homologous recombination at the RNA level via template switching between two ancient lentiviral genomes may have resulted in the transfer of part of the RT sequence between the pol and env domains of a pSIV ancestor, giving rise to a large portion of orf2, the putative tat homolog. This finding supports the potential key role of the highly error-prone lentiviral reverse transcriptase in generating new viral variants through reshuffling of their genomes [20].

Fig. 3. Alignment between a 71 aa region of the RT domain of the primate lentiviruses and the orf2 (46 aa)−env (25 aa) junction of pSIV.

Shading of the different positions represents the level of sequence conservation using the BLOSUM 62 amino acid substitution matrix in BioEdit (Hall, 2004). In addition, each asterisk indicates positions where pSIV amino acids are shared with at least one other primate lentivirus sequence. Accession numbers of the sequences are listed in Table S2. Phylogenetic Analyses

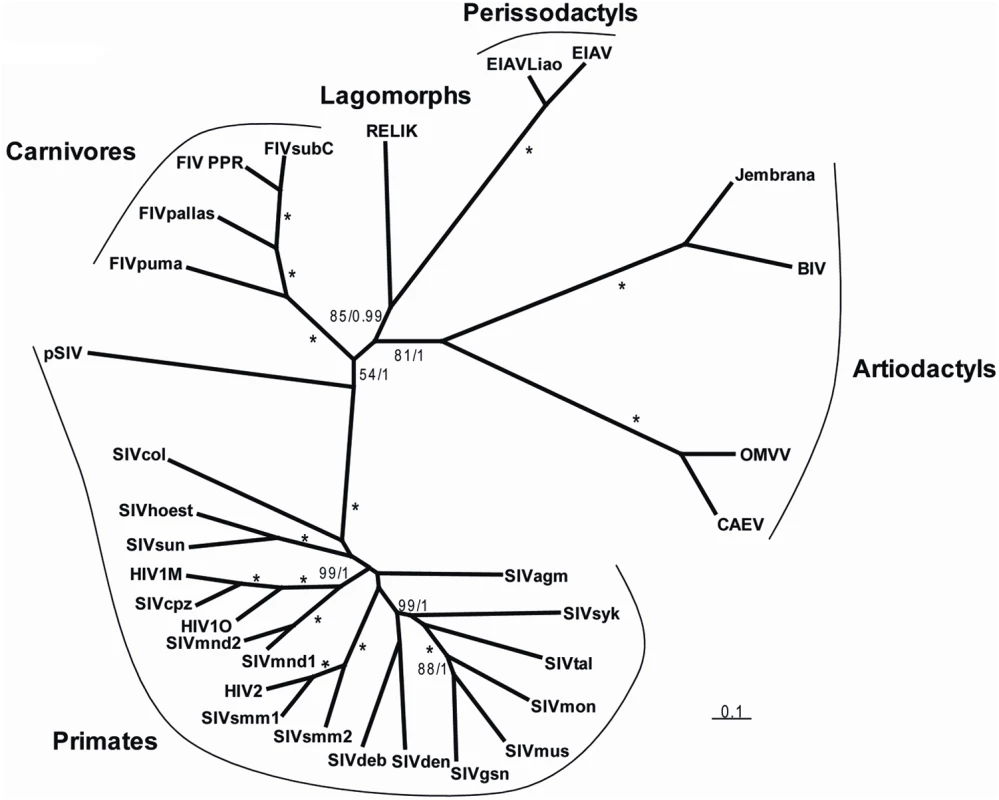

In order to formally assess the phylogenetic relationships between pSIV and other retroviruses, we performed Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analyses of the well-conserved reverse transcriptase (RT) domain. Both methods unequivocally support the grouping of pSIV within the lentivirus clade (Figure S5). Furthermore, as the RT alone does not provide any phylogenetic resolution between the different genera of lentiviruses, we also conducted Bayesian and ML analyses of the pol and gag domains extracted from a diverse set of lentiviruses. Separate analysis of the two domains did not reveal any obvious recombination event, i.e., the gag tree was not incongruent with the pol tree (not shown). In agreement with Gifford et al. [12], the Bayesian analysis combining gag and pol provided strong support for a potential sister relationship between pSIV and other primate lentiviruses, but this grouping is somewhat equivocal since the support was much lower in the ML analysis (Figure 4). Regardless, we believe that pSIV is sufficiently distant from the other known lentiviruses to be considered as a distinct lentiviral species.

Fig. 4. Unrooted tree of lentiviruses obtained after phylogenetic analysis of an alignment including ∼2350 nucleotides of the gag-pol region.

Numbers associated to internal branches correspond to Bayesian posterior probabilities/bootstrap ML values. Asterisks indicate when an internal branch is supported by posterior probability = 1/bootstrap = 100. Accession numbers of the sequences are listed in Table S2. The alignment used for the analyses is provided in Dataset S2. How Many pSIV Germline Infiltrations?

The Malgasy lemurs form a monophyletic group composed of four families (Cheirogaleidae (∼21 spp), Indriidae (11 spp), Lemuridae (19 spp) and Lepilemuridae (8 spp)) [21] that is thought to have colonized Madagascar only once, between 60 and 50 my ago, most likely by rafting across the Mozambique Channel from East Africa [22]. As within the Cheirogaleidae family Microcebus is more closely related to Mirza than to Cheirogaleus [23] (Figure 2, 5), the presence of pSIV insertions in Microcebus and Cheirogaleus but not in Mirza (Figure 2, S3) implies that pSIV either infiltrated the germline of the ancestor of the three genera and was subsequently lost in Mirza or alternatively, that it independently colonized the germline of the Cheirogaleus and Microcebus lineages. The first hypothesis would imply that the pSIV insertions are between ∼38 million years (my) (oldest date for the split between the clade grouping Microcebus, Cheirogaleus and Mirza and its sister taxa Lepilemur) and ∼19 my old (youngest date for the split between Cheirogaleus and the clade grouping Microcebus and Mirza) [23].

Fig. 5. PCR screening for presence/absence of orthologous solo LTR in various species of Malagasy lemurs.

For each locus, the larger PCR product indicates presence of the LTR, the smaller product indicates absence. (A) Primers (6160F: 5′-CAG CAK TTT CAT CAG CAA TTT G; 6160R: 5′-GCA AGC TGT GMC ACA TTT ATT BGC) were designed on the regions flanking the solo LTR in contig ABDC01306160. The expected size was ∼670 bp for presence and ∼250 bp for absence. (B) Primers (9233F: 5′-ATC TRT AGT CAA ATC CTG GG; 9233R: 5′-TAA TAC TCA CAA AAA CYT TAC C) were designed on the regions flanking the solo LTR in contig ABDC01159233. The expected size was ∼550 bp for presence and ∼130 bp for absence. (C) Primers (61523F: 5′-AAA TGA GTT TTG TTG CTC TRT YTC; 61523R: 5′-ATG TTR CTT TGG GTA GMT TG) were designed on the regions flanking the solo LTR in contig ABDC01361523. The expected size was ∼585 bp for presence and ∼165 bp for absence. The genus Eulemur and Propithecus belong to the family Lemuridae and Indriidae respectively. All the other species (genera Cheirogaleus, Microcebus and Mirza) belong to the family Cheirogaleidae. The tree depicts the phylogenetic relationships of the species and their divergence times according to [23],[41]. See Table S4 for the voucher specimen numbers of the lemur samples used in this study. Under the single germline infiltration hypothesis, the total genetic distance between the different pSIVfdl and pSIVgml copies should correspond to the mutations accumulated on both Microcebus and Cheirogaleus lineages under the neutral substitution rates of these species. These genetic distances vary between 0.038 in gag and 0.076 substitutions per site in env (average = 0.05) (Figure 1). Using the neutral substitution rate previously estimated for bushbaby (Otolemur garnetti), an African prosimian, (3×10−9 substitutions per site per year) [24], we can infer an approximate insertion time ranging from 6.3 to 12.6 my (average = 8.4 my), i.e., significantly younger than the split of Cheirogaleus and Microcebus (19–35 my). Therefore, the level of divergence between pSIVfdl and pSIVgml does not seem consistent with a single germline infiltration that would have occurred in the common ancestor of these lemurs and rather indicates that pSIV independently infiltrated the germline of Microcebus and Cheirogaleus after these two genera diverged from each other.

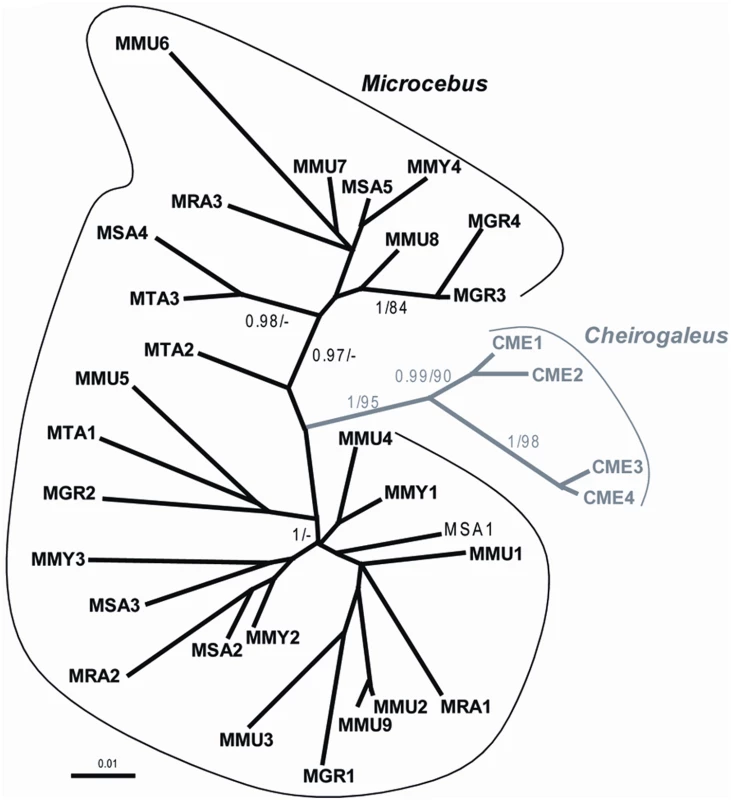

Also consistent with the hypothesis of two independent germline infiltrations, the Southern blot (Figure 2) and PCR screening (Figure 5) of pSIV insertions in six Microcebus species and Cheirogaleus did not reveal any shared orthologous insertion between Microcebus and Cheirogaleus, as would be expected under the single ancestral germline infiltration model. In addition, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of multiple pSIV LTRs from the different species of Microcebus and from C. medius yielded two distinct monophyletic clades that correspond to the two lemur genera (Figure 6). This shows that pSIVfdl and pSIVgml most likely derive from two closely related but distinct circulating lentiviruses, although the possibility of a gene conversion effect that would have homogenized the different LTRs in both species cannot be excluded [25].

Fig. 6. Unrooted tree of several LTRs (9<n<3) obtained in each of the following species of Malagasy lemurs.

MMU: Microcebus murinus, MRA: M. ravelobensis, MTA: M. tavaratra, MSA: M. sambiranensis, MMY: M. myoxinus, MGR: M. griseorufus, CME: Cheirogaleus medius. See Table S4 for the voucher specimen numbers of the lemur samples used in this study. Numbers associated to internal branched correspond to Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥0.95/bootstrap ML values ≥80. The alignment used for the analyses is provided in Dataset S3. Given the low number of pSIV proviruses, the lack of coding sequence for most of them (solo LTRs) and the high level of similarity between the pSIVfdl copies, we did not attempt to identify the mechanism(s) that produced multiple copies in the different lemur genomes. They could result from repeated germline insertions of the same or very similar circulating lentiviruses, intragenomic retrotransposition events, reinfection by an endogenized copy, or a mix of these mechanisms. For simplicity, we therefore refer to all insertions in each species using the term “germline infiltration” but we acknowledge that each insertion may or may not correspond to a different endogenization event, i.e, the integration of one exogenous virus in the germline followed by its vertical transmission to offspring and fixation in the species.

How Old Are the Two pSIVs Germline Infiltrations?

In order to estimate the time of the pSIVgml insertions in the Microcebus genome, we sequenced four orthologous solo LTRs shared by different Microcebus spp. (see Figure 5). Genetic distances between the most divergent species was between 0.015 and 0.038 substitutions per site (average = 0.025) (Table S3), which corresponds to an approximate insertion time of between 2.5 and 6.2 my (average = 4.2 my), again seemingly incompatible with a single germline infiltration event predating the Cheirogaleus/Microcebus split ∼19–38 my ago. Interestingly, M. murinus shares at least one orthologous insertion with each of the five other Microcebus species (Figure 5), suggesting that the germline infiltration of pSIVgml in the Microcebus genus occurred before the speciation of the extant taxa, i.e., between 3.5 and 7.3 my ago (Figure 5) [23], which is consistent with our molecular clock estimates. We note, however, that none of the orthologous pSIVgml insertions examined was shared by all Microcebus species. The most likely explanation for this pattern is that each insertion was fixed or eliminated after these species diverged from each other through idiosyncratic lineage sorting of ancestral polymorphism, a phenomenon well documented in Microcebus [26].

Our dating of pSIV germline integrations (2.5 and 6.2 my; average = 4.2 my) is older than the one inferred by Gifford et al. [12] (1.9–3.8 my). These authors relied solely on a comparison of two LTRs that they interpreted as an allelic polymorphism for a full-length pSIVgml and its solo LTR remaining after recombinogenic deletion of the rest of the provirus. However, a closer inspection of the raw sequence reads used for WGS assembly reveals that this apparent polymorphism is an artifact resulting from an assembly error, a common occurrence in low-coverage draft genome sequences. We experimentally confirmed that these LTRs actually originate from two different loci erroneously associated due to the genome misassembly (as described above and in Figure S1). Our dating method, which combines sequence divergence comparisons and cross-species analysis of orthologous insertions, provides a more reliable estimate of the age of pSIVgml germline infiltration.

Because pSIV apparently colonized at least twice independently the germline of lemurs, the total genetic distance between pSIVfdl and pSIVgml copies is expected to be the sum of (i) the mutations accumulated under the host neutral substitution rate on both Microcebus and Cheirogaleus branches since the time of each germline infiltration and (ii) the mutations accumulated under the viral substitution rate during the time separating the two germline infiltrations. As shown above, the average divergence between pSIVfdl and pSIVgml is 0.05 substitutions per site. We have also calculated the number of substitutions that occurred on pSIVgml since it integrated in the Microcebus germline, which is half of the orthologous LTR divergence, i.e., 0.025/2 = 0.0125 substitution per site. The cumulative number of substitutions that occurred on pSIV under the viral mutation rate and under the Cheirogaleus neutral substitution rate since germline infiltration is therefore approximately 0.05−0.0125 = 0.0375 substitutions per site. Lentiviral substitution rates differ from mammalian neutral substitution rates by 6 orders of magnitudes. The HIV substitution rate has been estimated to vary between 10×10−3 (synonymous substitutions) and 2×10−3 substitutions per site per year (non synonymous substitutions in gag-pol) [27]. Remarkably, under these rates, 0.0375 substitutions per site (as observed in pSIVfdl) are generated in only 3.75–18.75 years. Given the large difference between viral and mammalian neutral substitution rates, it is unlikely that any of the approximations made above would change this value by more than one or two orders of magnitude. This indicates that the time window separating the two germline infiltrations of pSIV was extremely narrow and thus these events must have occurred quasi simultaneously on an evolutionary time scale.

Conclusions

In this study, we have confirmed the presence of an endogenous lentivirus in the genome of the Malagasy prosimian Microcebus murinus and its relatively close phylogenetic relationship with modern simian lentiviruses, as reported recently [12]. Given that Madagascar has been isolated from Africa for 160 million years [28], the presence of a lentivirus on this island raises several intriguing questions concerning the time, mode, and direction of the transfer of pSIV between Africa and Madagascar (see Gifford et al. [12] for a comprehensive discussion on this issue).

In addition, we have demonstrated that pSIV is also present in low copy numbers in the genome of several other species of Microcebus and in another Malagasy prosimian, Cheirogaleus medius. While the various pSIVgml insertions in Microcebus species are most likely the result of a single germline infiltration that occurred around 4.2 my ago before the split of the Microcebus genus, those detected in Cheirogaleus most likely stem from a second, independent germline infiltration, that occurred concomitantly to the one in Microcebus. These two synchronous lentiviral colonizations of the germline of two non-sister lemur genera are striking given the paucity of hitherto characterized endogenous lentiviruses. It is possible that they have been facilitated either by a broader cell tropism of pSIV (or at least of the particular variants of pSIV that led to endogenization) compared to most other lentiviruses, or that the germ cells of lemurs are particularly prone to lentiviral endogenization. In addition, the present geographic distributions of Cheirogaleus and Microcebus species widely overlap on Madagascar [29],[30]. Sympatry of the two genera, if already occurring at the time of pSIV endogenizations, may have also facilitated the horizontal transfer of pSIV between these lemurs. Although one study provides evidence of SIV antigens in the Malagasy ring tailed lemurs (diverged from the ancestor of Microcebus and Cheirogaleus between 45.8−33.4 my ago) based on western blot analysis [31], there is no direct evidence of circulating lentiviruses in prosimian primates. A systematic screening of the native Malagasy mammalian fauna for the presence of endogenous and/or exogenous lentiviruses might help us further our understanding of the origin and spread of pSIV and lentiviruses in general.

Finally, the inclusion of multiple copies of pSIVs allowed us to fill the different gaps that are apparent in the pSIVgml sequence, and to infer an apparently intact pSIV consensus suitable for experimental reconstruction and functional analysis. In this respect, it is noteworthy that our pSIV consensus contains a complete capsid domain and pol-env intervening region, with the later potentially encoding an accessory gene situated in the typical location and of the same size as vif. The capsid domain and vif accessory gene of HIV are known to interact respectively with TRIM5alpha [32] and APOBEC3 [33], two mammalian protein families involved in the restriction of lentiviruses and other retroviruses in their host. The identification of these two components in pSIV may allow testing of their interactions with TRIM5alpha and APOBEC3 proteins, which could further our understanding of the impact of these defense systems in shaping the evolution of lentiviruses.

Materials and Methods

PCR/Cloning/Sequencing

The PCR primers designed to amplify pSIV fragments in Microcebus and Cheirogaleus are listed in Table S1. Those used for the screening of presence/absence of orthologous solo-LTRs in the various species of lemurs and for testing the validity of contigs containing pSIV fragments are given in the caption of Figure S1 and 5. Standard PCR conditions were: 2 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 30 s at 48–62°C, and 30 s–2 min at 72°C. PCR mix was: Buffer (5×), 5 ul; MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 ul; dNTP (10 mM), 0.5 ul; Primer 1 (10 uM), 1 ul; Primer 2 (10 uM), 1 ul; Taq (GoTaq, Promega), 1.25 U; DNA, 30–100 ng; and H2O up to 25 ul. PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen) and 4–6 randomly selected clones were sequenced on an ABI 3130XL sequencer. All sequences have been submitted to Genbank (Accession numbers: FJ707322–FJ707359).

Southern Blot

Genomic Southern blots were prepared by digesting completely ∼5 µg of total genomic DNA from Microcebus murinus, M. griseorufus, M. ravelobensis, Mirza coquereli, Cheirogaleus medius, Propithecus tattersalli, Eulemur fulvus and Homo sapiens (Hela cells) with XbaI (Promega). The digests were run overnight in a 0.8% agarose gel and blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blots were hybridized in PerfectHyb Plus hybridization buffer (Sigma) at 65°C either with a ∼1-kb fragment of the pSIVgml env domain or with a ∼300 bp fragment of the pSIVgml LTR. Membranes were washed in 2×/0.1% SDS or 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 65°C (i.e., medium to high stringency).The two probes were generated by PCR using the Env-F/6061-R1 and LTR-F/LTR-R primers respectively (Table S1), and subsequently [α-32P]dCTP-labelled (Random Primed DNA Labeling Kit, Roche). See Table S4 for the voucher numbers of the tissue samples used in this study. A picture of the ethidium bromide stained gels used to prepare the blots is shown in Figure S2.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Three sets of phylogenetic analyses were conducted. The first one aimed at assessing formally the phylogenetic relationships between pSIV and other retroviruses and was based on an alignment including the 150 most conserved amino acids of the reverse transcriptase domain extracted from of a set of various retroviruses. The second one aimed at evaluating the support for a putative sister relationship between pSIV and other described primate lentiviruses and was based on an alignment including the 2350 most conserved nucleotides of gag-pol of all lentiviruses for which whole genome sequence is available. We also conducted phylogenetic analyses of a number of LTRs sequenced in the various species of lemurs in order to test whether pSIV was endogenized once in the common ancestor of Cheirogaleus+Microcebus or twice independently on the Cheirogaleus and Microcebus lineages. Sequences were aligned by hand using BioEdit [34] and the alignments (available in Datasets S1, S2 and S3) were submitted to Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood analyses using MrBayes [35] and PHYML [36]. For both types of analyses, we used the GTR+I+G model for the nucleotide dataset, as suggested by the AIC criterion in MrModeltest [37] and the rtREV model [38] for the amino acid dataset. Bayesian analyses were run for 5 million generations with a sampling frequency of one tree/set of parameters every 100 generations. 12,500 trees were discarded as burn-in before summarizing the tree samples. Maximum Likelihood support was evaluated via nonparametric bootstrap analyses using 1000 pseudo replicates of the original matrix. Accession numbers of the sequences used together with the pSIV consensus to construct the alignments are listed in Table S2.

Dating

Genetic distances between paralogous and orthologous pSIV copies were calculated in MEGA 4.1 [39] using the Jukes-Cantor correction. The bushbaby (Otolemur garnetti) is the closest species to Malagasy lemurs for which an estimate of neutral substitution rate is available. In this species, neutral rates were estimated to vary between 2.83×10−9 and 3.29×10−9 substitutions per site per year based on the analysis of several families of ancestral repeats [24]. We used the average of these values, i.e., 3×10−9 (SD = 0.2×10−9; n = 4).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HahnBH

ShawGM

De CockKM

SharpPM

2000 AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Science 287 607 14

2. WorobeyM

GemmelM

TeuwenDE

HaselkornT

KunstmanK

2008 Direct evidence of extensive diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa by 1960. Nature 455 661 4

3. HolmesEC

2003 Molecular clocks and the puzzle of RNA virus origins. J Virol 77 3893 3897

4. GiffordRJ

2006 Evolution at the host-retrovirus interface. Bioessays 28 1153 1156

5. CoffinJM

HughesSH

VarmusHE

1997 Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Press 843

6. GiffordR

TristemM

2003 The evolution, distribution and diversity of endogenous retroviruses. Virus Genes 26 291 315

7. LöwerR

LöwerJ

KurthR

1996 The viruses in all of us: characteristics and biological significance of human endogenous retrovirus sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 5177 84

8. StoyeJP

2006 Koala retrovirus: a genome invasion in real time. Genome Biol 7 241

9. KatzourakisA

TristemM

PybusOG

GiffordRJ

2007 Discovery and analysis of the first endogenous lentivirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 6261 5

10. KeckesovaZ

YlinenLM

TowersGJ

GiffordRJ

KatzourakisA

2008 Identification of a RELIK orthologue in the European hare (Lepus europaeus) reveals a minimum age of 12 million years for the lagomorph lentiviruses. Virology. In press

11. van der LooW

AbrantesJ

EstevesPJ

2008 Sharing of endogenous lentiviral gene fragments among leporid lineages separated for more than 12 million years. J Virol. In press

12. GiffordRJ

KatzourakisA

TristemM

PybusOG

WintersM

2008 A transitional endogenous lentivirus from the genome of a basal primate and implications for lentivirus evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 20362 20367

13. HughesJF

CoffinJM

2004 Human endogenous retrovirus K solo-LTR formation and insertional polymorphisms: implications for human and viral evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 1668 72

14. TaylorBS

SobieszczykME

McCutchanFE

HammerSM

2008 The challenge of HIV-1 subtype diversity. N Engl J Med 358 1590 602

15. HopeTJ

1997 Viral RNA export. Chem Biol 4 335 344

16. PollardVW

MalimMH

1998 The HIV-1 Rev protein. Annu Rev Microbiol 52 491 532

17. TristemM

MarshallC

KarpasA

PetrikJ

HillF

1990 Origin of vpx in lentiviruses. Nature 347 341 342

18. SharpPM

BailesE

StevensonM

EmermanM

HahnBH

1996 Gene acquisition in HIV and SIV. Nature 383 586 7

19. TristemM

PurvisA

QuickeDLJ

1998 Complex evolutionary history of primate lentiviral vpr genes. Virology 240 232 237

20. PathakVK

HuWS

1997 “Might as well jump!” Template switching by retroviral reverse transcriptase, defective genome formation, and recombination. Semin Virol 8 141 150

21. GrovesC

2005 Order primates.

WilsonDE

ReederDM

Mammal's species of the world. John Hopkins University press 111 119

22. PouxC

MadsenO

MarquardE

VietesDR

de JongWW

VencesM

2005 Asynchronous colonization of Madagascar by the four endemic clades of primates, tenrecs, carnivores, and rodents as inferred from nuclear genes. Syst Biol 54 719 730

23. HorvathJE

WeisrockDW

EmbrySL

FiorentinoI

BalhoffJP

2008 Development and application of a phylogenomic toolkit: Resolving the evolutionary history of Madagascar's lemurs. Genome Res 18 489 499

24. PaceJKII

GilbertC

ClarkMS

FeschotteC

2008 Repeated horizontal transfer of a DNA transposon in mammals and other tetrapods. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 17023 17028

25. HughesJF

CoffinJM

2005 Human endogenous retroviral elements as indicators of ectopic recombination events in the primate genome. Genetics 171 1183 94

26. HeckmanKL

MarianiCL

RasoloarisonR

YoderAD

2007 Multiple nuclear loci reveal patterns of incomplete lineage sorting and complex species history within western mouse lemurs (Microcebus). Mol Phylogenet Evol 43 353 367

27. LiWH

TanimuraM

SharpPM

1988 Rates and dates of divergence between AIDS virus nucleotide sequences. Mol Biol Evol 5 313 330

28. StoreyM

MahoneyJJ

SaundersAD

DuncanRA

KelleySP

1995 Timing of hot spot-related volcanism and the breakup of Madagascar and India. Science 267 852 855

29. SchwabD

GanzhornJU

2004 Distribution, population structure and habitat use of Microcebus berthae compared to those of other sympatric Cheirogalids. Int J Primatol 25 307 330

30. RasoloarisonR

GoodmanSM

GanzhornJU

2000 A taxonomic revision of mouse lemurs (Microcebus) occurring in the western portion of Madagascar. Int J Primatol 21 963 1019

31. SondgerothK

BlitvichB

BlairC

TerweeJ

JungeR

2007 Assessing flavivirus, lentivirus, and herpesvirus exposure in free-ranging ring-tailed lemurs in southwestern Madagascar. J Wildl Dis 43 40 47

32. TowersGJ

2007 The control of viral infection by tripartite motif proteins and cyclophilin A. Retrovirology 4 40

33. Goila-GaurR

StrebelK

2008 HIV-1 Vif, APOBEC, and intrinsic immunity. Retrovirology 5 51

34. HallT

2004 BioEdit version 5.0.6. Available: http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html

35. HuelsenbeckJP

RonquistF

2001 MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17 754 755

36. GuindonS

GascuelO

2003 A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52 696 704

37. NylanderJAA

2004 MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University

38. DimmicMW

RestJS

MindellDP

GoldsteinRA

2002 rtREV: an amino acid substitution matrix for inference of retrovirus and reverse transcriptase phylogeny. J Mol Evol 55 65 73

39. TamuraK

DudleyJ

NeiM

KumarS

2007 MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24 1596 1599

40. KuikenC

LeitnerT

FoleyB

HahnB

MarxP

2008 HIV Sequence Compendium 2008 Los Alamos, New Mexico Los Alamos National Laboratory, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics LA-UR 08-03719. Available: http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/

41. YangZ

YoderAD

2003 Comparison of likelihood and Bayesian methods for estimating divergence times using multiple gene loci and calibration points, with application to a radiation of cute-looking mouse lemur species. Syst Biol 52 705 716

42. TheisC

ReederJ

GiegerichR

2008 KnotInFrame: prediction of -1 ribosomal frameshift events. Nucleic Acids Res 36 6013 20

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Neocentromeres Come of Age

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2009 Číslo 3

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Neocentromeres Come of Age

- Mitotic Recombination: Why? When? How? Where?

- Life, Death, Differentiation, and the Multicellularity of Bacteria

- Capturing the Spectrum of Interaction Effects in Genetic Association Studies by Simulated Evaporative Cooling Network Analysis

- Measures of Autozygosity in Decline: Globalization, Urbanization, and Its Implications for Medical Genetics

- Ciliary Beating Recovery in Deficient Human Airway Epithelial Cells after Lentivirus Gene Therapy

- Parallel Germline Infiltration of a Lentivirus in Two Malagasy Lemurs

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Neocentromeres Come of Age

- Capturing the Spectrum of Interaction Effects in Genetic Association Studies by Simulated Evaporative Cooling Network Analysis

- Mitotic Recombination: Why? When? How? Where?

- Life, Death, Differentiation, and the Multicellularity of Bacteria

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání