-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Individual Blood Cell Telomere Attrition Rate Is Telomere Length Dependent

Age-associated telomere shortening is a well documented feature of peripheral blood cells in human population studies, but it is not known to what extent these data can be transferred to the individual level. Telomere length (TL) in two blood samples taken at ∼10 years interval from 959 individuals was investigated using real-time PCR. TL was also measured in 13 families from a multigenerational cohort. As expected, we found an age-related decline in TL over time (r = –0.164, P<0.001, n = 959). However, approximately one-third of the individuals exhibited a stable or increased TL over a decade. The individual telomere attrition rate was inversely correlated with initial TL at a highly significant level (r = –0.752, P<0.001), indicating that the attrition rate was most pronounced in individuals with long telomeres at baseline. In accordance, the age-associated telomere attrition rate was more prominent in families with members displaying longer telomeres at a young age (r = –0.691, P<0.001). Abnormal blood TL has been reported at diagnosis of various malignancies, but in the present study there was no association between individual telomere attrition rate or prediagnostic TL and later tumor development. The collected data strongly suggest a TL maintenance mechanism acting in vivo, providing protection of short telomeres as previously demonstrated in vitro. Our findings might challenge the hypothesis that individual TL can predict possible life span or later tumor development.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 5(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000375

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000375Summary

Age-associated telomere shortening is a well documented feature of peripheral blood cells in human population studies, but it is not known to what extent these data can be transferred to the individual level. Telomere length (TL) in two blood samples taken at ∼10 years interval from 959 individuals was investigated using real-time PCR. TL was also measured in 13 families from a multigenerational cohort. As expected, we found an age-related decline in TL over time (r = –0.164, P<0.001, n = 959). However, approximately one-third of the individuals exhibited a stable or increased TL over a decade. The individual telomere attrition rate was inversely correlated with initial TL at a highly significant level (r = –0.752, P<0.001), indicating that the attrition rate was most pronounced in individuals with long telomeres at baseline. In accordance, the age-associated telomere attrition rate was more prominent in families with members displaying longer telomeres at a young age (r = –0.691, P<0.001). Abnormal blood TL has been reported at diagnosis of various malignancies, but in the present study there was no association between individual telomere attrition rate or prediagnostic TL and later tumor development. The collected data strongly suggest a TL maintenance mechanism acting in vivo, providing protection of short telomeres as previously demonstrated in vitro. Our findings might challenge the hypothesis that individual TL can predict possible life span or later tumor development.

Introduction

Telomeres are protective end structures of the chromosomes. Telomere length is dictated partly by hereditary [1]–[6] and partly by environmental [7],[8] and epigenetic factors [9]. The hereditary impact on TL has been estimated to range between 36–84% [3]–[6]. An equally strong telomere length inheritance was reported for monozygotic (MZ) as for dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs, indicating that the correlation in TL was mainly due to shared environmental factors [10]. In contrast, relatively minor environmental effects on TL during life were suggested in MZ twins where identical homologue telomeres differed less in TL compared to the two alleles within one individual [1],[2]. Regarding the influence of life style and environment on telomere maintenance, the published data are conflicting and no consensus has been reached concerning the impact of e.g. smoking, blood pressure or serum lipids on TL (literature overview in [11]).

Patients with smoking associated malignancies, such as human bladder, head and neck, lung, and renal cell cancers, have been shown to display shorter blood TL at diagnosis compared to controls [12],[13]. Short blood TL has therefore been suggested as a predisposition factor for these cancer types. For breast cancer, no difference in blood TL between patients and controls was found in one study [14], whereas we recently reported longer telomeres in peripheral blood cells of breast cancer patients and, furthermore, that long blood TL indicated a poor survival [15]. Numerous studies have shown an inverse correlation between blood cell TL and age [16]–[18]. Hence, it might be assumed that this characteristic is also true at the individual level. However, data are essentially lacking on individual telomere attrition rates and its relation to the occurrence of malignancy. Martin-Ruiz et al. did not find an association between telomere length at baseline and malignancy related mortality in a longitudinal study on individuals >85 years old [19].

In the present study, we have investigated individual blood cell telomere shortening in a large cohort of voluntarily donated samples. Our novel results show that the attrition rate was strongly correlated to telomere length at baseline, but unrelated to later tumor development.

Results

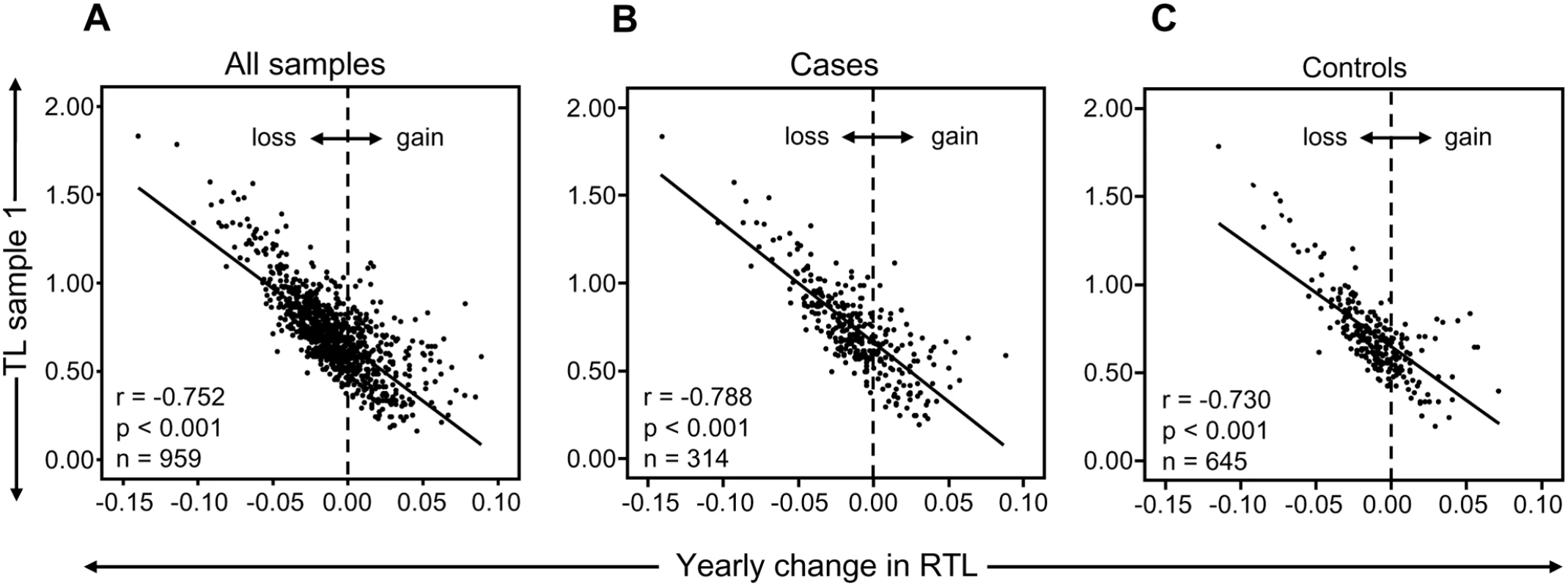

In the study cohort of 959 individuals, investigated at two occasions with 9–11 year intervals, an overall TL shortening occurred with age as expected (r = −0.164, P<0.001) and women displayed longer telomeres than men (P = 0.052, after age-adjustments). However, about one third (34%) of all individuals demonstrated a stable TL or even elongated their telomeres over approximately a decade. There were very little differences between cases and controls (31.8% and 34.9%, respectively). When the individual telomere attrition per year was plotted against the relative TL (RTL) value of sample 1, a very strong and inverse correlation was found (r = −0.752, P<0.001; n = 959) (Figure 1A). This finding was also observed when analyzing tumor cases (r = −0.788, P<0.001; n = 314) and controls (r = −0.730, P<0.001; n = 645) separately (Figure 1B and 1C) To make sure that the strong correlation was not based on the very highest or lowest RTL values, the analysis was also made on individuals with RTL values <1 and >0.3. This subcohort showed the same statistical outcome (r = −0.623, p<0.001). Moreover, there was no gender difference (men: r = −0.781, p<0.001, women: r = −0.737, p<0.001). Hence, the attrition rate was most pronounced in individuals displaying the longest telomeres at baseline.

Fig. 1. RTL and yearly telomere loss over a 9–11 year period.

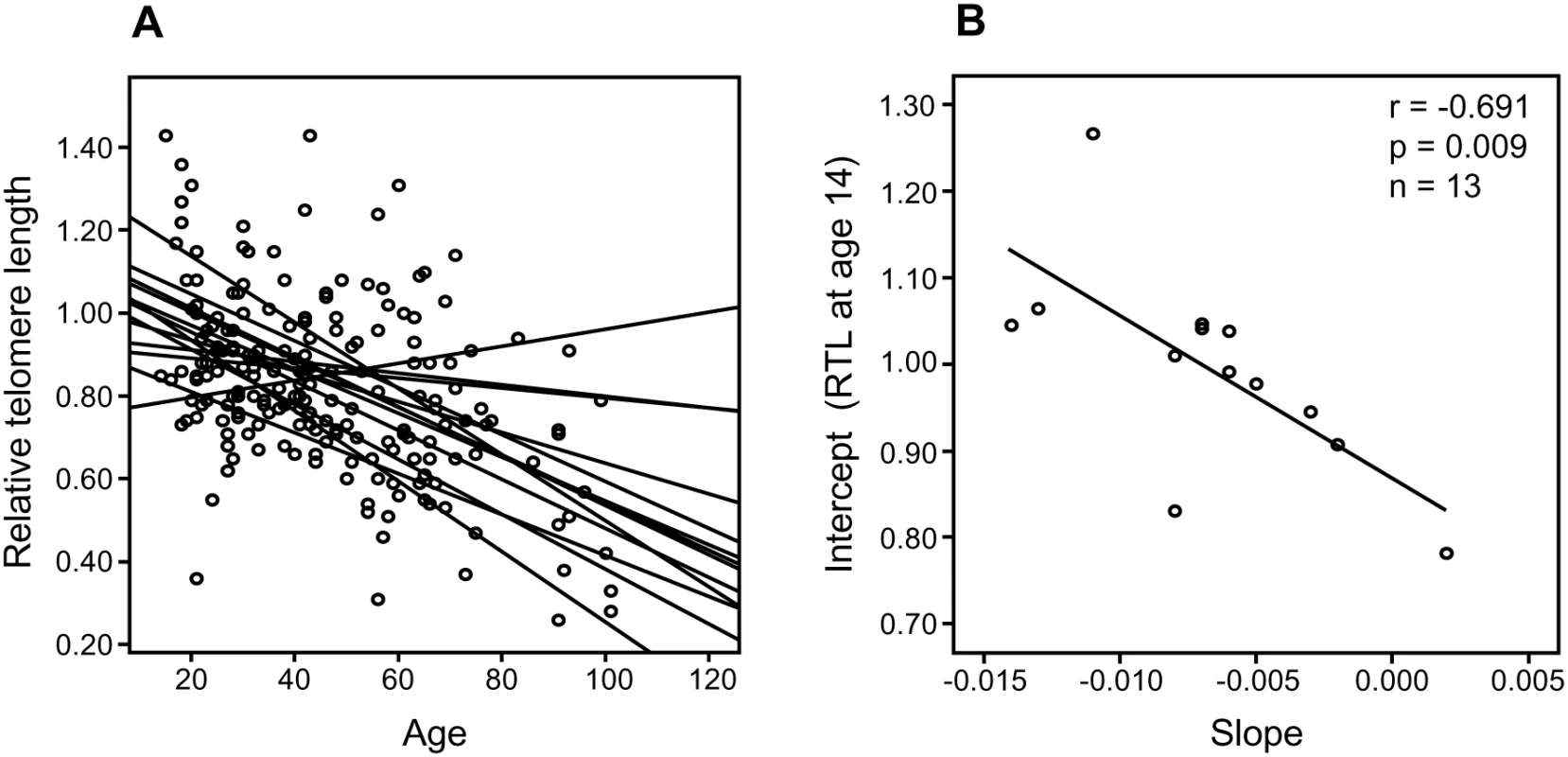

(A) There was a highly significant and inverse correlation between RTL in sample 1 and telomere attrition rate. The inverse correlation between RTL in sample 1 and attrition rate was similar for (B) future tumor patients and (C) controls. In a separate cohort of multigenerational families, we selected 13 families encompassing ≥10 members over at least three generations, and plotted RTL against age. A parallellity test revealed statistically significant differences in slope and intercept values between the 13 families (P<0.001), i.e. the families differed with regard to telomere shortening over time (Figure 2A). When the slope value from each family was plotted as a function of the corresponding intercept, it was found that RTL at young age (intercept estimated for the age of 14) was highly correlated with the telomere attrition rate (slope) (r = −0.691, P = 0.009) (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. Correlation between RTL and attrition rate in 13 separate families.

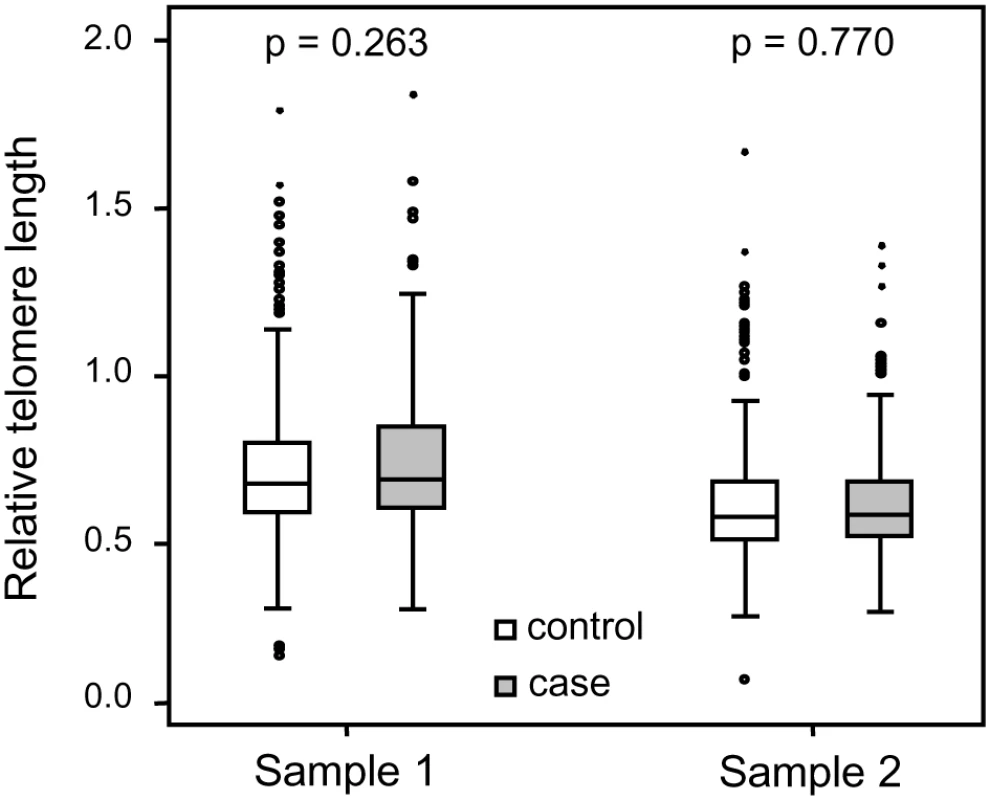

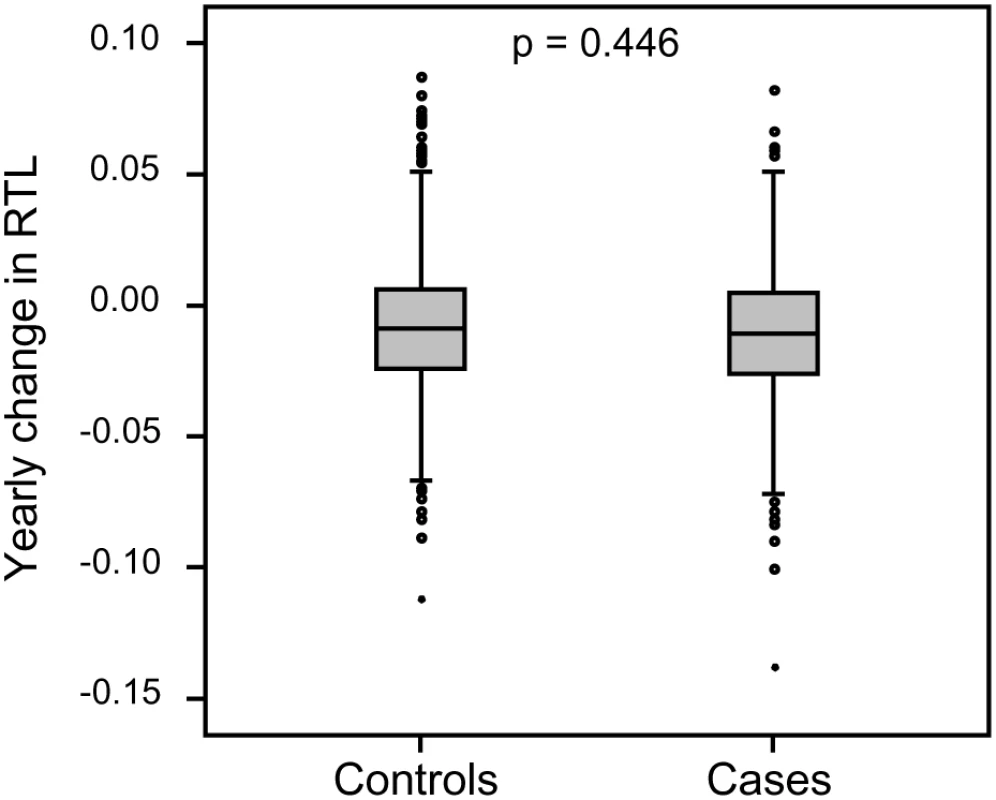

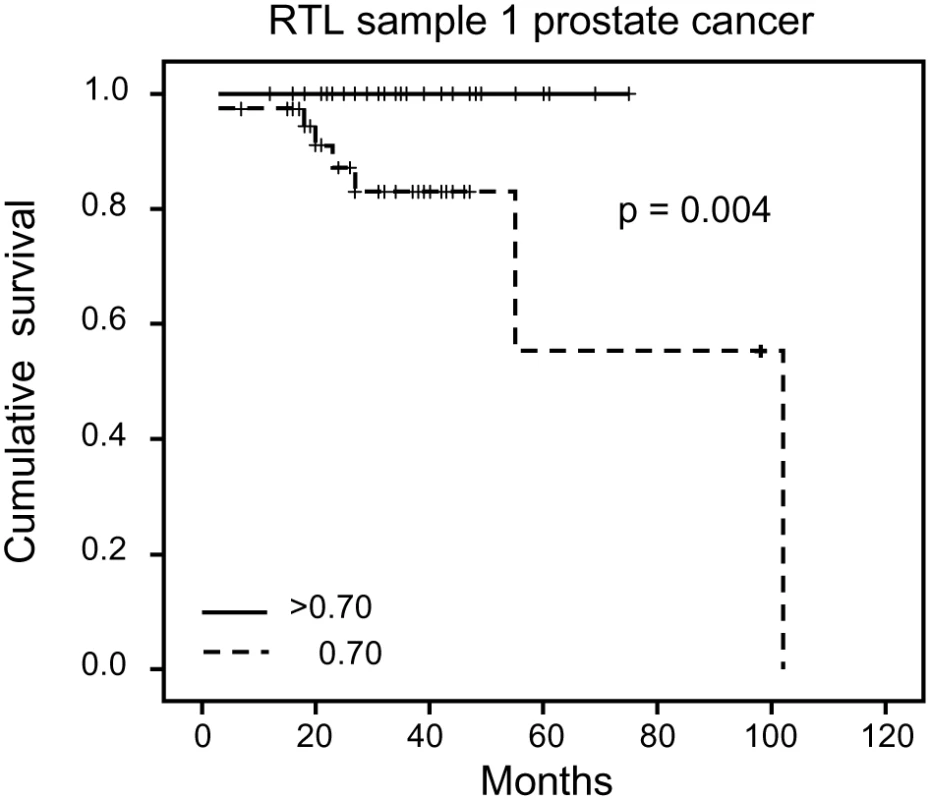

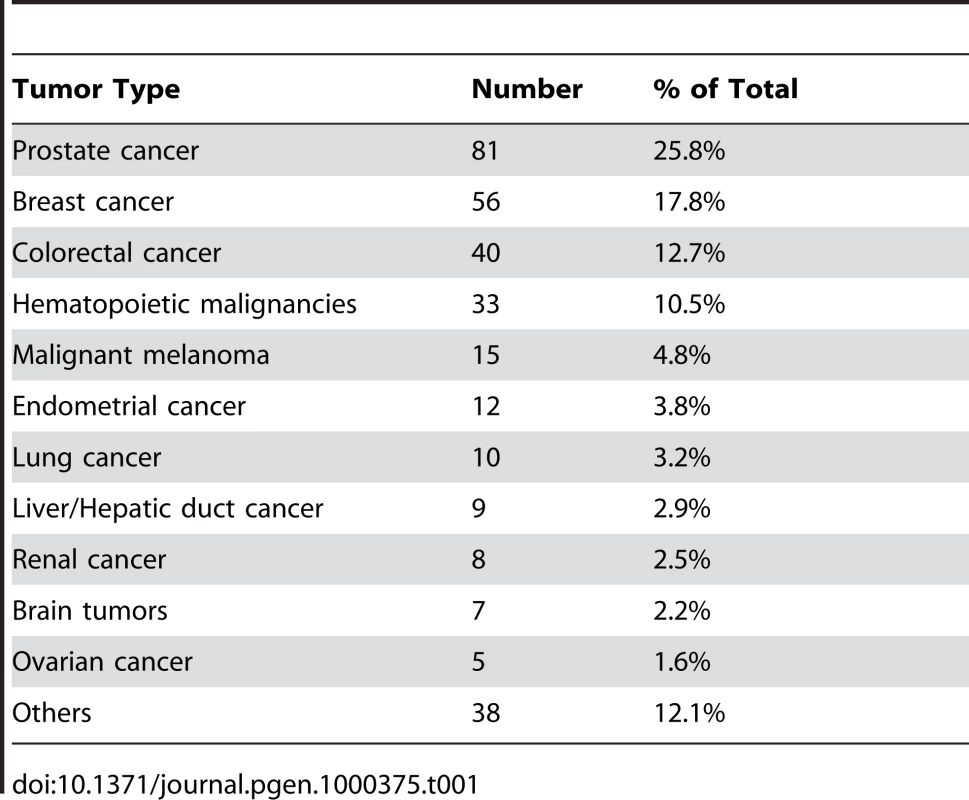

Each family contained 10 or more (maximum 28) related individuals (i.e., no in-laws). (A) Illustration of telomere shortening with age in 13 individual families. The separate regression lines were obtained by plotting RTL vs. age for each individual in a family. (B) Telomere attrition rate (i.e. slope) in the 13 families in relation to the estimated RTL at age 14 in each family, showing a strong negative correlation. RTL in sample 1 or 2 did not differ between cases and controls after age-adjustment (Figure 3), indicating that blood TL was not a potential biomarker for tumor development in prediagnostic samples. The telomere attrition rate was similar for cases and controls (P = 0.446 after age and sex adjustments) (Figure 4). As expected, prostate and breast cancer were the most common tumor types (the distribution of different types is given in Table 1), and due to the relatively short follow up time after diagnosis (0–113, mean 34 months) events of deaths were few. When all tumor cases were analyzed as one group, shorter than median RTL (for all tumor cases) in sample 1 (≥9 years before diagnosis) indicated a poor prognosis (not shown in figure). This is illustrated in the largest tumor group, prostate cancer (n = 81), where all deaths were found in the short RTL group in sample 1 (P = 0.004; cut off = median RTL value for prostate cancer cases) (Figure 5). When the same analysis was performed for RTL in sample 2 (collected 0–11 years before diagnosis) no significant prognostic difference was found between prostate cancer patients with long versus short telomeres (P = 0.174). Moreover, no association between telomere attrition rate and prognosis was found neither in the entire tumor group nor in the prostate cancer group (P = 0.266 and P = 0.889, respectively).

Fig. 3. Blood RTL could not predict future tumor development.

There was no difference between future tumor patients and controls regarding RTL measured ≥9 years before diagnosis (RTL sample 1) or measured 0–11 years before diagnosis (RTL sample 2). Fig. 4. Individual telomere attrition rate was not a marker for future tumor development.

Yearly telomere loss at the individual level did not differ between future tumor patients and controls. Fig. 5. Blood RTL and prognosis in prediagnostic samples from prostate cancer patients.

Shorter than median RTL ≥9 years before diagnosis was associated with decreased survival. Tab. 1. Distribution of different tumor types.

Discussion

Age-associated telomere shortening is a generally accepted finding based on large cross-sectional studies. It has been assumed that this characteristic telomere attrition is true at the individual level as well. It has also been speculated that the telomere attrition rate in blood cells of tumor patients is higher compared to controls. The present longitudinal study cohort demonstrated the expected decline in telomere length by time, but we also observed large individual differences. Actually, in about one third of all individuals an elongation of the telomeres occurred over a decade. Most interestingly, individuals displaying the longest telomeres at the first blood draw demonstrated the most pronounced telomere shortening over time, and vice versa. The average coefficient of variation for the method was ∼6% and some of the variation in TL might be related to the technique itself. However, to make sure that the strong correlation was not based on the very highest or lowest RTL values, the correlation analysis was also made on individuals with RTL values <1 and >0.3. The result of the restricted correlation analysis was very similar to the result of the larger analysis, showing a strong correlation between telomere length at baseline and attrition rate.

A large variation in telomere attrition at the individual level has been observed in previous longitudinal studies on telomere length [19]–[21]. In a very recent study by Aviv et al. [21], TL was measured in leukocytes collected on two occasions from 450 whites and 185 African Americans, participating in the Bogalusa Heart Study. The median time period between the first and second blood sampling was shorter compared to our study (∼6 years vs. ∼10 years), and the participants were fewer and younger (age range: 20.0–40.0 years at baseline). Nevertheless, they found that the age-dependent TL attrition rate was proportional to TL at baseline, which is in accordance to our present study. The majority of participants in their study displayed TL shortening (85.9% of African Americans and 88.0% of whites), whereas the rest displayed a stable or increased TL. Similar to our observation, they also found that the rate of TL shortening varied considerably among individuals.

One explanation to the variations in attrition rate could be differences in epigenetic regulation, with secondary effects on telomere maintenance. Another reason might be that telomerase act preferentially on short telomeres, which has been shown in mice models and cell culture systems [22]–[26]. This would be in line with our observation of a very strong inverse correlation between individual TL at baseline and telomere attrition over time. Interestingly, we found a similar result in our separate family cohort. Hence, comparable data were obtained when analyzing telomere attrition rate at both the individual and at the family level. In the present study, individuals with the shortest TL actually elongated their telomeres over a decade, indicating that the TL maintenance machinery is focused on protecting the shortest telomeres. Nevertheless, other factors are likely to influence the TL attrition rate as well. In our study, the correlation value between blood RTL at baseline (sample 1) and attrition rate was r = −0.752 when analyzing the entire cohort. The corresponding r-squared value is hence 0.566, or ∼57%. This means that the telomere length at time point 1 could explain 57% of the variation in attrition rate. Thus, 43% of the variation might well be explained by other factors, such as life style, oxidative stress, inflammation etc. In the study by Aviv et al. [21], oxidative stress was proposed as a potential candidate for causing proportional telomere shortening. We agree that oxidative stress is likely to be important for telomere attrition, but the theory does not explain why a subset of the cohort demonstrated TL elongation. We suggest that a cellular TL regulating mechanism, rather than environmental/life style factors, is the major factor determining the rate of telomere attrition over time.

The working hypothesis that blood cell TL can indicate a later development of a malignant tumor was not supported in the present study. This hypothesis emanates from data showing altered TL in cases with a variety of malignancies. In urinary bladder, head and neck, lung, and renal cell cancers, shortened blood telomeres have been described at diagnosis, whereas data on breast cancer indicate unchanged or longer telomeres compared to controls [12]–[15]. Since no difference in TL existed between cases and controls, neither ≥9 (sample 1) nor 0–11 (sample 2) years before the appearance of a malignancy, we conclude that blood TL is not a prediagnostic biomarker for malignancy per se. However, our cases suffered from a variety of tumors and we cannot exclude that blood TL might be a biomarker for specific tumor types. A support for this is a recent study indicating that short blood telomeres were associated with a decreased risk for melanoma but also an increased risk for basal cell carcinoma, whereas there was no trend for squamous cell carcinoma [27].

In the largest tumor group in our material, prostate cancer, the blood TL ≥9 years before diagnosis seemed to indicate a poor prognosis. All prostate cancer cases with long blood telomeres (>median) were alive five years after diagnosis compared to <60% in the group with short telomeres. However, in the sample taken 0–11 years before prostate cancer diagnosis, TL did not give prognostic information. Thus, since the same prostate cancer patients were studied at different time points ahead of the cancer diagnosis, a shift had occurred indicating differences in the rate of telomere loss. This shift is interesting, since for breast cancer, blood TL at diagnosis seems to be a strong prognostic biomarker, with longer telomeres associated with a worse prognosis [15]. We have obtained similar data for renal cell carcinoma [Svenson et al., unpublished data] indicating that this feature is not unique for breast cancer. Unfortunately, in the present material the other cancer groups were too small to allow this type of statistical calculations. The biological background for these findings is unclear but it is tempting to speculate that factors responding to the presence of a tumor also have an impact on telomere maintenance, especially in immune reactive cells and their precursors. Due to few events in the cancer group a more definitive analysis of prediagnostic TL in relation to prognosis must await longer follow up times.

In conclusion, and similar to what have been observed in cultured cells in vitro, human blood cells in vivo seem to have a telomere maintenance system that gives priority to short telomeres. Based on human cross-sectional studies of age-associated telomere attrition, it has been speculated that TL at a certain age can predict a theoretical future life span. Our findings indicate that TL regulation through life might be more complex than previously known, complicating such life span predictions. We suggest that, at least in blood cells, the main TL regulator is a general mechanism that senses the telomere length similar to the counting mechanism demonstrated in cells from different species [28]–[31]. However, it might well be possible to avoid excessive telomere loss by living a healthy life as recently indicated [32]. Our data has important implications for our understanding of human telomere biology and for future analyses of telomere maintenance mechanisms in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohorts

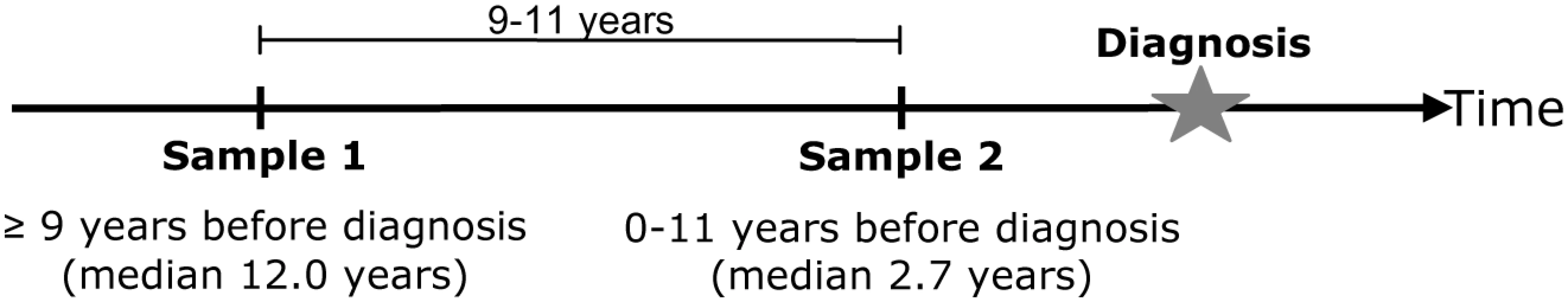

The North Sweden Health and Disease Study (NSHDS) include the Västerbotten Intervention Project (VIP), launched in 1985 in the County of Västerbotten, the cardiovascular research program Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Diseases (MONICA) and the local Mammography Screening Project (MSP) [33]. At present the population based NSHDS collection contains samples from around 85000 individuals, nearly all Caucasians. Blood was drawn with anticoagulants, separated into plasma, erythrocyte and buffy coat fractions and stored at −80°C in small aliquots. In the NSHDS collection we identified >7000 individuals who had donated blood samples at a ∼10 year interval (9–11 years) and of these 343 persons had obtained a cancer diagnosis after the second blood sample (time from sample 2 to diagnosis: 0–11 years, mean 2.7) (Figure 6). From the same cohort, 686 age and sex matched controls were also selected. The age span was 30–61 years for sample 1 and 40–70 years for sample 2. Cancer cases were identified through record linkages with the regional Cancer Register. Due to insufficient amounts of buffy coat cells for DNA extraction or unsuccessful RT-PCR, 314 cases and 645 controls (totally 1918 samples) were included in the statistical analyses (cases: 176 men and 138 women; controls: 361 men and 284 women).

Fig. 6. Schematic drawing of blood draws for sample 1 (baseline) and sample 2 (follow up).

To permit analysis of a possible family linked pattern regarding TL attrition, a multifamily cohort was also utilized, initially aimed at studying genetic and environmental factors influencing heredity of personality traits, upbringing, general health and longevity (a study designed and conducted in the late 90's by the author RA). In total, whole blood was available from 962 individuals in 68 families (445 men and 517 women) with an age span of 0–102 years. Thirteen of these families could be selected for the purpose of this study (se statistics below).

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Umeå University Ethical Committee.

Telomere Length Determination

DNA was extracted from buffy coats and whole blood using conventional methods. Relative telomere length was measured using quantitative real-time PCR as described previously [34],[35]. In short, telomeres and a single copy gene (β2-globin) were amplified in all samples including an internal reference control cell line (CCRF-CEM) to which all samples were compared. The ΔΔCt method was used for calculation of RTL values and a standard curve was created in each PCR run to monitor the PCR efficiency. The mean inter-assay coefficient of variation for this method ranges between 4–8% in our laboratory.

Statistics

Normality was shown regarding RTL distributions. Pearson partial correlation was performed to calculate age-adjusted correlations between continuous variables. ANCOVA was used for age and/or sex adjusted comparisons between groups. Cumulative survival for cancer patients with long vs. short telomeres was investigated using Kaplan-Meier with the log-rank test. Survival was defined as the number of months between diagnosis date to death or to last follow-up (Feb 2008).

To investigate whether the rate of telomere loss with age was linked to TL at a young age, 13 separate families in the multifamily cohort were studied. In each family, samples from 10 or more (maximum 28) related individuals, i.e. no in-laws, were available in at least three generations. The age of the individuals in the youngest generation varied between 14 and 32 years and in the oldest generation between 70 and 101 years. The number of men and women was similar within all families except for one which contained more women. The RTL values were plotted against age and linear regression was used to generate intercept (“starting RTL”) and slope (telomere loss) values for each family. The calculated intercepts corresponded to the estimated RTL value at the age of 14. The slope was then plotted as a function of the intercept and the correlation was examined using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient. MLwiN [36], a software for multilevel analysis, was used to test for parallellity between the 13 regression lines. All other statistics were analyzed in SPSS 15.0. A P-value ≤0.05 was considered to be significant.

Zdroje

1. GraakjaerJ

Londono-VallejoJA

ChristensenK

KolvraaS

2003 The pattern of chromosome-specific variations in telomere length in humans is determined by inherited, telomere-near factors and is maintained throughout life. Mech Ageing Dev 124 629 640

2. GraakjaerJ

Londono-VallejoJA

ChristensenK

KolvraaS

2006 The pattern of chromosome-specific variations in telomere length in humans shows signs of heritability and is maintained through life. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1067 311 316

3. JeanclosE

SchorkNJ

KyvikKO

KimuraM

SkurnickJH

2000 Telomere length inversely correlates with pulse pressure and is highly familial. Hypertension 36 195 200

4. SlagboomPE

DroogS

BoomsmaDI

1994 Genetic determination of telomere size in humans: a twin study of three age groups. Am J Hum Genet 55 876 882

5. GraakjaerJ

Der-SarkissianH

SchmitzA

BayerJ

ThomasG

2006 Allele-specific relative telomere lengths are inherited. Hum Genet 119 344 350

6. Vasa-NicoteraM

BrouiletteS

ManginoM

ThompsonJR

BraundP

2005 Mapping of a major locus that determines telomere length in humans. Am J Human Genetics 76 147 151

7. BekaertS

De MeyerT

RietzschelER

De BuyzereML

De BacquerD

2007 Telomere length and cardiovascular risk factors in a middle-aged population free of overt cardiovascular disease. Aging Cell 6 639 647

8. RichterT

von ZglinickiT

2007 A continuous correlation between oxidative stress and telomere shortening in fibroblasts. Exp Gerontol 42 1039 1042

9. BlascoMA

2007 The epigenetic regulation of mammalian telomeres. Nat Rev Genet 8 299 309

10. HudaN

TanakaH

HerbertBS

ReedT

GilleyD

2007 Shared environmental factors associated with telomere length maintenance in elderly male twins. Aging Cell 6 709 713

11. NordfjällK

EliassonM

StegmayrB

MelanderO

NilssonP

2008 Telomere length is associated to obesity parameters but with a gender difference. Obesity In press

12. WuX

AmosCI

ZhuY

ZhaoH

GrossmanBH

2003 Telomere dysfunction: a potential cancer predisposition factor. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 1211 1218

13. ShaoL

WoodCG

ZhangD

TannirNM

MatinS

2007 Telomere dysfunction in peripheral lymphocytes as a potential predisposition factor for renal cancer. J Urol 178 1492 1496

14. BarwellJ

PangonL

GeorgiouA

DochertyZ

KestertonI

2007 Is telomere length in peripheral blood lymphocytes correlated with cancer susceptibility or radiosensitivity? Br J Cancer 97 1696 1700

15. SvensonU

NordfjällK

StegmayrB

ManjerJ

NilssonP

2008 Breast cancer survival is associated with telomere length in peripheral blood cells. Cancer Res 68 3618 3623

16. IwamaH

OhyashikiK

OhyashikiJH

HayashiS

YahataN

1998 Telomeric length and telomerase activity vary with age in peripheral blood cells obtained from normal individuals. Hum Genet 102 397 402

17. FrenckRW

BlackburnEH

ShannonKM

1998 The rate of telomere sequence loss in human leukocytes varies with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 5607 5610

18. NordfjällK

LarefalkA

LindgrenP

HolmbergD

RoosG

2005 Telomere length and heredity: Indications of paternal inheritance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 16374 16378

19. Martin-RuizCM

GusseklooJ

van HeemstD

von ZglinickiT

WestendorpRG

2005 Telomere length in white blood cells is not associated with morbidity or mortality in the oldest old: a population-based study. Aging Cell 4 287 290

20. GardnerJP

LiS

SrinivasanSR

ChenW

KimuraM

2005 Rise in insulin resistance is associated with escalated telomere attrition. Circulation 111 2171 2177

21. AvivA

ChenW

GardnerJP

KimuraM

BrimacombeM

2008 Leukocyte telomere dynamics: longitudinal findings among young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol In press

22. TeixeiraMT

ArnericM

SperisenP

LingnerJ

2004 Telomere length homeostasis is achieved via a switch between telomerase - extendible and -nonextendible states. Cell 117 323 335

23. OuelletteMM

LiaoM

HerbertBS

JohnsonM

HoltSE

2000 Subsenescent telomere lengths in fibroblasts immortalized by limiting amounts of telomerase. J Biol Chem 275 10072 10076

24. ZhuL

HathcockKS

HandeP

LansdorpPM

SeldinMF

1998 Telomere length regulation in mice is linked to a novel chromosome locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 8648 8653

25. SamperE

FloresJM

BlascoMA

2001 Restoration of telomerase activity rescues chromosomal instability and premature aging in Terc−/ − mice with short telomeres. EMBO Rep 2 800 807

26. HemannMT

StrongMA

HaoLY

GreiderCW

2001 The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell 107 67 77

27. HanJ

QureshiAA

PrescottJ

GuoQ

YeL

2009 A prospective study of telomere length and the risk of skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol 129 415 421

28. MarcandS

GilsonE

ShoreD

1997 A protein-counting mechanism for telomere length regulation in yeast. Science 275 986 990

29. KrauskopfA

BlackburnEH

1996 Control of telomere growth by interactions of RAP1 with the most distal telomeric repeats. Nature 383 354 357

30. van SteenselB

de LangeT

1997 Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature 385 740 743

31. AncelinK

BrunoriM

BauwensS

KoeringCE

BrunC

2002 Targeting assay to study the cis functions of human telomeric proteins: evidence for inhibition of telomerase by TRF1 and for activation of telomere degradation by TRF2. Mol Cell Biol 22 3474 3487

32. CherkasLF

HunkinJL

KatoBS

RichardsJB

GardnerJP

2008 The association between physical activity in leisure time and leukocyte telomere length. Arch Intern Med 168 131 132

33. KaaksR

LundinE

RinaldiS

ManjerJ

BiessyC

2002 Prospective study of IGF-I, IGF-binding proteins, and breast cancer risk, in northern and southern Sweden. Cancer Causes Control 13 307 316

34. CawthonRM

2002 Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30 e47

35. NordfjällK

OstermanP

MelanderO

NilssonP

RoosG

2007 hTERT (-1327)T/C polymorphism is not associated with age-related telomere attrition in peripheral blood. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358 215 218

36. GoldsteinH

BrowneW

RasbashJ

2002 Multilevel modelling of medical data. Stat Med 21 3291 3315

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2009 Číslo 2

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The Individual Blood Cell Telomere Attrition Rate Is Telomere Length Dependent

- Conservation and Convergence of Colour Genetics: Mutations in Cavefish

- Expression of the Multiple Sclerosis-Associated MHC Class II Allele Is Regulated by Vitamin D

- When Segregation Hangs by a Thread

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Současné možnosti léčby obezity

nový kurzAutoři: MUDr. Martin Hrubý

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání